Abstract

Background

High blood pressure is increasing worldwide, disproportionately so in developing countries. Inadequate health care systems and adoption of unhealthy lifestyles have been linked to this emergent pattern. To better understand this trend, it is imperative we measure prevalence of hypertension, and examine specific risk factors, at a local level. This study provides a cross-sectional view of urban residents of Arusha City to determine prevalence and associated risk factors.

Methods

Blood pressure was measured using a digital sphygmomanometer. Interviews were conducted using the WHO STEPwise survey questionnaire to assess lifestyle factors. Dietary intake information was collected by a standardized Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic characteristics. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Pearson’s Chi Square (χ 2) tests were used to determine significant risk factors for hypertension, and multivariate log binomial regression was used to reveal potential predictors of hypertension. Dietary patterns were analyzed by principal component analysis.

Results

Approximately 45% of the study population was found to be hypertensive. The mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) of the sample was 102.3 mmHg (SD = 18.3). Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 136.3 (SD = 30.5) and 85.3 (SD = 16.1) mmHg, respectively. Through multivariate analysis, age and body mass index were found to be independently, positively, associated with hypertension. Adherence to ‘healthy’ dietary pattern was negatively independently associated with hypertension.

Conclusions

With nearly half of participants being hypertensive, this study suggests that hypertension is a significant health risk in Arusha, Tanzania. Obesity, healthy diet, and age were found to be positively associated with hypertension risk. This study did not establish any significant association between increased blood pressure and Western-dietary pattern, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and physical activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension (HTN) contributes to heart disease, kidney failure, stroke and numerous other morbidities [1]. Further, prevalence is climbing worldwide, but especially in developing countries. This is attributed to a combination of poor health systems and increasingly unhealthy lifestyles [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the highest prevalence globally is 46%, occuring in Africa [3]. Within sub-Saharan Africa, HTN prevalence varies significantly between urban and rural settings.

Hypertension can be avoided or controlled through lifestyle factors including diet, exercise, weight management, and avoiding smoking, excess alcohol and stress [4]. Because HTN does not present outward symptoms in the early stages, it often goes undetected, particularly in impoverished conditions where there is limited screening for non-communicable diseases [3]. The costs of undiagnosed and poorly managed HTN are extremely high for both the individual and society [5]. As such, it is important to understand the local conditions, allowing for better support for private and public initiatives to reduce risk, increase early detection, and improve treatment.

In this study, we conducted a cursory assessment of high blood pressure in urban Arusha City, in northern Tanzania. We established local HTN prevalence and examined specific risk factors, including dietary pattern. This study fills a knowledge gap and better prepares government, decision-makers, medical professionals, and residents to make informed policy, programming, and personal choices.

Methods

Study area

In keeping with economic conditions throughout East Africa, Tanzania has a very low gross domestic product [6]. Poverty rates are high (28.2% experiencing basic poverty and 9.7% living in extreme poverty); however, these rates have been improving in recent years [7]. Arusha City is located in Arusha Municipal District in northern Tanzania, close to the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro and near the border to Kenya. All residents of the district are considered urban (population 416,000) [8]. The city is divided into 25 municipal wards, four of which were randomly selected for this study.

Participant recruitment and data collection

Eligible participants were consenting adults reporting their home address within the wards of Muriet, Sekei, Sokon I or Unga Ltd. in Arusha City. Eight interview/screening sessions, and a number of follow up sessions, took place in various public community buildings (i.e., schools, local government offices, and clinics) in each of the wards, between April and May 2016. Participants were recruited through poster advertisement to attend the sessions in exchange for free medical advice based on their screening results.

Registration was completed upon arrival on a first come, first served basis. Weight and height were recorded using a spring scale and a measuring tape affixed to the wall, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Each participant’s BMI measurements were categorized as underweight, normal, overweight, and obese based on the standard cut-off points set by the WHO [9].

Blood pressure was measured at least fifteen minutes after arrival using a digital sphygmomanometer with automatic inflation (Life Brand™ BM60). Participants’ HTN status was provisionally classified based on blood pressure ranges consistent with the Seventh Joint National Committee [10]. Table 3 illustrates systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ranges used for HTN classification. When measured SBP or DBP were in differing classes, the more severe classification was applied. Participants with high blood pressure were urged to return for re-testing the following day, or referred to an medical clinic for urgent or follow-up care, as deemed most appropriate by our medical staff. Follow-up readings were used in this analysis.

Following physical screening, participants were interviewed using the standardized Swahili translated version of the WHO STEPwise© survey questionnaire consisting of core, expanded, and optional variables [11]. The frequency of total, vigorous, and moderate intensity physical activities was calculated per WHO STEPwise© survey manual [11]. Dietary intake information was collected by a standardized Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) assessing self-reported food intake over the previous year. The tool was previously developed and validated [12].

Data analysis

The data collected were entered in Excel™ and analyzed by Statistical Analysis System™ (SAS) Version 9.4 and SPSS™ Version 21. In all, 549 subjects were included in the study. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic characteristics. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables and by percentages for categorical variables. Pearson’s Chi Square (χ 2) tests were used to determine significant risk factors for HTN. Independent variables significantly associated with HTN in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate log binomial regression model to reveal potential associations with HTN. The independent variables considered include: gender, age, education level, employment, marital status, BMI, and dietary pattern. Alpha of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The final model included only the variables which were significantly associated with HTN.

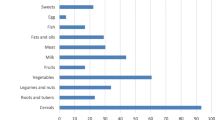

Dietary patterns were analyzed by first classifying the 58 food items of the FFQ into 12 food groups. This was to minimize within-person variations in intakes of individual foods. Principal component factor analysis was conducted to derive dietary patterns based on the 12 foods/groups. Factors were rotated by an orthogonal transformation (resulting in uncorrelated factors) to achieve a simpler structure with greater interpretability. Components with an eigenvalue >1,as well as the interpretability of the factors, were considered when determining the number of factors to maintain. The factor analysis generated three major dietary patterns. The first dietary pattern was labelled ‘healthy’ as it was loaded with carbohydrate rich foods, vegetables, fruits, and spices. The second major pattern was dubbed ‘Western’ due to high meat, milk, and fat intake. The least frequent dietary pattern was characterized by high intake of sweets, roots, and tubers and legumes and was called ‘complex carbohydrate’.

Results

General characteristics of the sample

A total of 549 man and women from the four random wards of Arusha City participated in the screening (demographics are shown in Table 1) and all were included in this analysis. The average age was 40.7 years (SD = 12.07), with all participants between 25 and 64 years. The majority of the participants, 34.6%, were in the 35 to 44 age range, while the fewest were 55 years and older (15.8%). Females were overrepresented, constituting 57.6% (n = 316) of the sample. Of the 549 participants, more than two thirds (81.2%) were educated up to a primary level, 86.2% were self-employed, and more than half (64.8%) were married or cohabiting.

Blood pressure

Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was calculated using the formula [(2*DBP) + SBP]/3. The mean MABP of the sample was 102.3 mmHg (SD = 18.3). Means for SBP and DBP were 136.3 (SD = 30.5) and 85.3 (SD = 16.1) mmHg, respectively (averages, by gender, are shown in Table 2). Nearly 45% of the study population was classified as hypertensive, 23% being stage 1 and 21.7% being stage 2 (see Table 3).

Univariate analysis of potential contributing factors of hypertension in Arusha, Tanzania

The results of univariate analysis demonstrate potential risk factors for HTN, shown in Table 4. The overall prevalence of HTN (Stage 1 and 2) was 44.7% and pre-hypertension is a further 32.6%. Males were more likely to be hypertensive than females (47.6% versus 42.4%) though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.22). Females were more likely to be pre-hypertensive (34.8% versus 29.4%). Hypertension risk was not significantly associated with the ‘Western’ diet or ‘complex carbohydrate’ diet (p = 0.518 and p = 0.352, respectively). Alcohol drinking at least once in the previous year (p = 0.083), and current smoking (p = 0.341) were also not significantly associated with HTN risk. As anticipated, ‘healthy’ dietary pattern was negatively associated with HTN (p = 0.01). Hypertension risk increased with age (p = 0.0001) and BMI (p = 0.005), but decreased with higher levels of education (p = 0.042) and doing vigorous physical activities (though not significantly, p = 0.058). The prevalence of HTN increased from 26.3% in the youngest age group to 70.1% in the oldest (p= > 0.0001). Risk doubled when comparing underweight individuals with obese (p = 0.005). The risk of HTN increased among those who did not meet criteria for moderate or total physical activities although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.103 and p = 0.167 respectively). There was statistically significant difference in HTN between different employment statuses where the self-employed individuals were more likely to be hypertensive (46.7%) than students or employees (p = 0.024).

Multivariate analysis of potential contributors to hypertension in Arusha Tanzania

Univariate analysis showed that age, education level, employment, BMI, and ‘healthy’ dietary pattern were significantly associated with HTN. These variables were subjected to multivariate logistics binomial regression. Upon building the model, education level, vigorous physical activity and employment were no longer significant correlates and were removed from the final model. Age, BMI and ‘healthy’ dietary pattern were independently associated with HTN (Table 5) and were maintained.

Ultimately, a positive association between HTN and age was supported. The risk of being hypertensive for groups aged 35–44 (ARR = 1.64, CI: 1.22–2.20) and 45–54 (ARR = 2.25, CI: 1.67–3.03) was almost twice that of the 18-34 year olds, and three times greater for those aged 55–79 (ARR = 2.50, CI: 1.88–3.32). Compared to obese participants, those who were underweight (ARR = 0.44, CI: 0.20–0.94) and normal weight (ARR = 0.78, CI: 0.64–0.96) had significantly lower prevalence of HTN. Though not significant, overweight individuals are also less likely to be hypertensive than the obese (ARR = 0.93, CI: 0.77–1.14). Following a ‘healthy’ dietary pattern was significantly negatively correlated with HTN (ARR = 0.82, CI: 0.68–0.99).

Discussion

There are few comparable studies of HTN prevalence and associated risk factors specific to the Arusha City, Tanzania. Our co-authors (JB and PP) have previously investigated HTN prevalence in a comparative study amongst urban Arusha Massai (27.7%) and their rural, traditional counterparts (10.7%) [13]. In another study of predominantly Maasai participants migrating from nearby Simanjiro to Arusha City, 21.4% HTN prevalence was described [14]. Maasai in Arusha City are a minority population, and tend to have very different body morphology and dietary practices than the other, more predominant, residents of Arusha City. Maasai tend to grow very tall, are typically very thin, and traditionally live a nomadic life, not cultivating or relying heavily on carbohydrate rich foods, instead deriving the majority of nutrition from meat and dairy from their cattle and goats. It would not be appropriate to compare findings from studies of Maasai to our study population as diet and body type are known correlates to HTN risk. Further, the Simanjiro study specifically excluded participants with an established HTN diagnosis and therefore does not represent the overall HTN prevalence [14].

Two older studies (1999 and 2002), found HTN rates in Tanzanian’s largest coastal city, Dar es Salaam, to be similarly around 30% [15, 16]. Given the worldwide trend towards increasing HTN predominance, those figures are likely an underestimation of current rates [2]. In the city of Mwanza, in northwestern Tanzania, HTN amongst males only was 23.7% [17]. We would anticipate a typical diet in Mwanza to be derived of a greater proportion of fish as it is located on Lake Victoria, where fishing is a major industry. This may account, partially, for HTN risk difference. In a recent study across four countries in sub-Saharan Africa, age standardized HTN prevalence was 25.9% [18]. On the other hand, researchers have found much higher HTN rates in other parts of Africa, including in Cameroon, where 47.5% of the study population was found to be hypertensive [19].

Our findings demonstrated a higher-than-typical HTN prevalence in our Arusha City study than suggested by the aforementioned Maasai or nearby studies. In part, this may be attributed to our methodology and limited resources which did not allow for repeat blood pressure analysis per recommended diagnostic guidelines [10]. Anxiety with the screening process and unfamiliarity with blood pressure equipment can elevate initial blood pressure readings [14]. Overall, our results were consistent with the extant literature with respect to major risk factors for HTN including male gender, increased BMI [13,14,15, 17, 19, 20], and age [14, 15, 17, 19].

Our study demonstrated the protective effect of eating a healthy diet, but did not establish a significant risk between unhealthy ‘Western’ diets and increased HTN. Njelekela et al. have shown that salt intake and coconut milk consumption are significantly correlated with increased blood pressure in men and women, respectively, in a study of Tanzanian 47–57 year olds [21]. They also demonstrated that, whether one lives pastorally, rurally or in an urban space, there are marked differences in the overall foods sources most drawn from, which, naturally has an effect on HTN risk. This is consistent with the migration study by Unwin et al., who found a protective effect of consuming local porridge, and showed a marked change in eating habits and increase weight and waist circumference when moving from rural to an urban environment [14].

Limitations

There are limitations to our study that should not be overlooked when interpreting these findings. The methodology used to establish HTN risk is not-conclusive. As blood pressure does not remain consistent, and can be made to temporarily elevate, averages of multiple blood pressure readings over time are customary [10]. Further, volunteer bias likely favored participation by unemployed or underemployed individuals who could wait most of the day for a free medical consultation. This same population may suffer lower socioeconomic status and lower health status than the average resident in Arusha City, which may play a role in HTN risk. Our study size of 549 participants represents a minute portion of the Arusha City population.

With respect to dietary pattern, salt was not specifically addressed in the FFQ. Doing so may have offered an additional depth of understanding as dietary salt is known to be associated with blood pressure. As with all principal component factor analysis, determining the number and labels of dietary patterns, and interpretation of results, is somewhat subjective [22]. Further, this study does not consider the confounding effect of additional HTN risk factors such as stress.

Conclusion

This study confirms the high prevalence of HTN in developing countries as it has been reported in other studies. Evidence from this study demonstrates that diet, obesity and unhealthy lifestyles have a role to play in the trend of rising HTN levels in developing countries. Hypertension, if not controlled, will result into other severe forms of cardiovascular diseases. In the worldwide crisis of cardiovascular disease, it is important to understand local contributing factors and conditions. This study has better clarified how eating patterns in Arusha are related to HTN and has established an estimate of HTN prevalence in four local wards. Taken together, these findings can be used to encourage policy-makers to place HTN screening, literacy and prevention campaigns at the forefront of their priorities.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DBP:

-

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Strauer, B.E., Hypertensive heart disease. 2012: Springer Science & Business Media.

World Health Organization. A global brief on hypertension. Geneva: WHO, 2013 [cited 2016 August 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/79059.

Nulu S, Aronow WS, Frishman WH. Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a contextual view of patterns of disease, best management, and systems issues. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24(1):30–40. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000083.

Carrera-Bastos P, et al. The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization. Res Rep Clin Cardiol. 2011;2:15–35.

Ataklte F, et al. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):291–8. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308066.147.

World Bank Group. Washington: World Bank Group. Gross domestic product 2015; July [cited 2016 September 5]. Available from http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf.

World Bank Group. Washington: World Bank Group. Tanzania Mainland Poverty Assessment; 2015 [cited 2016 September 7] Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/Africa/Tanzania/Report/tanzania-poverty-assessment-05.2015.pdf.

United Republic of Tanzania. Arusha, Tanzania: National Bureau of Statistics; 2016 p. 18–28 [cited 2016 August 31].Basic demographic and socio-economic profile. Available from: http://www.tanzania.go.tz/egov_uploads/documents/Descriptive_tables_Tanzania_Mainland_sw.pdf.

World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO. Global database on body mass index; 2016 [cited 2016 May 8] Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Bethesda: National Institute of Health; 2004. [cited 2016 May 27] Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdf.

World Health Organization. WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS). Geneva: WHO; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 20] Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/manual/en.

Jordan I, Hebestreit A, Swai B, Krawinkel MB. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk among women in northern Tanzania: a case-control study. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52(3):905–15.

Ngoye A, Petrucka P, Buza J. Differences in hypertension risk factors between rural Maasai in Ngorongoro and urban Maasai in Arusha municipal:adescriptive study. Int J Life Sci. 2014;1(1):17–31.

Unwin N, James P, McLarty D, Machybia H, Nkulila P, Tamin B, et al. Rural to urban migration and changes in cardiovascular risk factors in Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010 ;10(1):272 [cited 2016 August 1] Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-272.

Edwards R, Unwin N, Mugusi F, Whiting D, Rashid S, Kissima J, et al. Hypertension prevalence and care in an urban and rural area of Tanzania. J Med Med Sci. 2013;4(4):149–54.

Bovet P, Gervasoni JP, Mkamba M, Balampama M, Lengeler C, Paccaud F. Low utilization of health care services following screening for hypertension in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): a prospective population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:407. [cited 2016 August 1]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-407.

Njelekela M, Muhihi A, Mpembeni R, Masesa Z, Kitamori K, Mori M, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among young and middle-aged men in urban Mwanza, Tanzania. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2011;19(6):553–61.

Guwatudde D, Nankya-Mutyoba J, Kalyesubula R, Laurence C, Adebamowo C, Ajayi I, et al. The burden of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a four-country cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1211. [cited 2016 August 15]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2546-z.

Dzudie A, Kengne AP, Muna WFT, Ba H, Menanga A, Kouam CK, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a self-selected sub-Saharan African urban population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012 [cited 2016 August 15];2(4):1–10. Available from: <Go to ISI>://MEDLINE:22923629\n<Go to ISI>://WOS:000315049300074.

Bovet P, Ross AG, Gervasoni J-P, Mkamba M, Mtasiwa DM, Lengeler C, et al. Distribution of blood pressure, body mass index and smoking habits in the urban population of Dar es salaam, Tanzania, and associations with socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):240–7.

Njelekela M, Sato T, Nara Y, Miki T, Kuga S, Noguchi T, et al. Nutritional variation and cardiovascular risk factors in Tanzaniarural-urban difference. S Afr Med J. 2003 93(4):295–299. [cited 2016 august 15]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12806724.

Martinez ME, Marshall JR, Sechrest L. The arbitrary nature of the factor analytical process. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(1):17–9.

Acknowledgments

In addition to funding support, the authors would like to acknowledge the Green Hope Organisation - Mama Kwanza Project, for technical and material supports. We are also thankful to the Saskatchewan Cancer Agency for additional material support.

Funding

The study was funded by the Government of Tanzania through Nelson Mandela African Institution of Science and Technology and the Mama Kwanza Project.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified datasets used and analyzed for the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LK, JB, and PP developed the study protocols, conducted the literature reviews, and drafted the original manuscript. JB and PP supervised the project. LK, TN, and DM conducted the data collection and analysis, and contributed to manuscript development. EM and AM provided statistical and data analysis expertise to the project. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the National Institute of Medical Research Ethical Committee of Tanzania. Additional permission to conduct this study was granted by Arusha City Council. Formal written consent was obtained from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Katalambula, L.K., Meyer, D.N., Ngoma, T. et al. Dietary pattern and other lifestyle factors as potential contributors to hypertension prevalence in Arusha City, Tanzania: a population-based descriptive study. BMC Public Health 17, 659 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4679-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4679-8