Abstract

Background

Online ride-hailing is a fast-developing new travel mode. However, tobacco control policies on its drivers remain underdeveloped. This study aims to reveal the status and determine the influencing factors of ride-hailing drivers’ smoking behaviour to provide a basis for the formulation of tobacco control policies.

Methods

We derived our cross-sectional data from an online survey of full-time ride-hailing drivers in China. We used a survey questionnaire to collect variables, including sociodemographic and work-related characteristics, health status, health behaviour, health literacy and smoking status. Finally, we analysed the influencing factors of current smoking by conducting chi-square test and multivariate logistic regression.

Results

A total of 8990 ride-hailing drivers have participated in the survey, in which 5024 were current smokers, accounting to 55.9%. Nearly one-third of smokers smoked in their cars (32.2%). The logistic regression analysis results were as follows: male drivers (OR = 0.519, 95% CI [0.416, 0.647]), central regions (OR = 1.172, 95% CI [1.049, 1.309]) and eastern regions (OR = 1.330, 95% CI [1.194, 1.480]), working at both daytime and night (OR = 1.287, 95% CI [1.164, 1.424]) and non-fixed time (OR = 0.847, 95% CI [0.718, 0.999]), ages of 35–54 years (OR = 0.585, 95% CI [0.408, 0.829]), current drinker (OR = 1.663, 95% CI [1.526, 1.813]), irregular eating habits (OR = 1.370, 95% CI [1.233, 1.523]), the number of days in a week of engaging in at least 10 min of moderate or vigorous exercise ≥3 (OR = 0.752, 95% CI [0.646, 0.875]), taking the initiative to acquire health knowledge occasionally (OR = 0.882, 95% CI [0.783, 0.992]) or frequently (OR = 0.675, 95% CI [0.591, 0.770]) and underweight (OR = 1.249, 95% CI [1.001, 1.559]) and overweight (OR = 0.846, 95% CI [0.775, 0.924]) have association with the prevalence of current smoking amongst online ride-hailing drivers.

Conclusion

The smoking rate of ride-hailing drivers was high. Sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and health-related factors affected their smoking behaviour. Psychological and behavioural interventions can promote smoking control management and encourage drivers to quit or limit smoking. Online car-hailing companies can also establish a complaint mechanism combined with personal credit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Online ride-hailing refers to the business activities of providing non-cruise booking taxi service based on a service platform that integrates information of supply and demand relying on Internet technology [1]. Compared with the traditional taxi, it has the advantages of high efficiency, good experience, convenience, and low price [2, 3]. Online ride-hailing services are rapidly growing in many countries. Currently, DiDi, Grab, Lyft, Ola, and other ride-hailing platforms have covered thousands of cities and built a global network [4]. In China, Didi Chuxing Technology Co., as the largest mobile travel platform, provided over 7.43 billion mobile trips to 450 million passengers in more than 400 cities in 2017 [5]. As an emerging travel mode, online ride-hailing plays an increasingly significant role in people’s daily travel, with a user volume of 362 million in China by March 2020 [6].

A wide-reaching survey in China reported that the occupational group of taxi drivers generally has a high smoking rate [7,8,9] due to various factors, such as long working hours, high intensity of work and the need to refresh themselves when they are tired [10, 11]. Regular smoking can cause various malignant tumours and respiratory system, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular system and other systemic diseases. In addition, smoking in a narrow and closed carriage imposes health risks to passengers and danger during driving [12].

In 2011, the detailed rules for the Regulations on the Administration of Sanitation at Public Places issued by the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China stipulated for the first time the contents of smoking control in public transport. In accordance with our review of local government documents, at present, 90% of Chinese provincial administrative regions have issued policies and regulations banning smoking in public transport. However, the definition of public transport varies from city to city, and only a few provinces, such as Beijing and Sichuan Province, have listed taxis as non-smoking public vehicles. The nature of online car-hailing is between a traditional taxi and private car [1]. Its position is not clear, and the existing smoking ban policy fails to restrain it, making it a blind spot for anti-smoking management. Prior research showed that high smoking rates could lead to low compliance with tobacco regulations [13]. Coupled with incomplete national policies on smoking control in online ride-hailing vehicles, second-hand smoke exposure in the cars is inevitable. Thus, the smoking status and related factors of the occupational group of ride-hailing drivers require further investigations. Yet, relevant studies remain lacking.

Local and international studies have determined various influencing factors of adult smoking, including gender [14,15,16,17], marital status [18, 19], educational level [20], economic level [21], social networks [22, 23], health status [24, 25], mental illness [26,27,28], alcohol/drug abuse and dependence [29,30,31,32], race/ethnicity [33] and work pressure [34, 35], etc. Moreover, Hu et al. [36] and Li et al. [37] pointed out that the effect of skipping breakfast, short sleep duration, and participation in recreational activities and physical exercises on the smoking behaviour of rural residents was significant. Specific factors influence a certain population. For example, prior studies showed that job-related stressors affected the increase of smoking intensity and nicotine dependence of American military personnel [38]; the smoking behaviour of spouses affected the smoking during pregnancy of women [39]; shift work affected the smoking of manufacturing workers [40]. At present, only a few investigated the factors influencing drivers’ smoking. Norman GJ et al. [41] and Josh Martin et al. [42] reported that households and regions with low economic level had associations with low smoke exposure rate in cars. By contrast, households and regions with high economic levels were related to high smoke exposure rates in cars. Jain NB et al. [43] showed that job title, education level, residential area, scale and location of truck transport terminals were determinants of smoking amongst truck transport drivers. Ozoh OB et al. [44] studied the prevalence and related factors of smoking amongst commercial long-distance drivers in Lagos, Nigeria. They found that smoking friends, freight driving and low educational level were the factors affecting current smoking. To sum up, the factors influencing smoking in drivers, such as demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, are highly similar to those in adults. The occupational characteristics of drivers themselves can also affect their smoking behaviour.

On the basis of the above discussion, we designed a survey questionnaire for online ride-hailing drivers in China. The current developments of online ride-hailing provide a convenient way to conduct large scale online survey. Therefore, using a platform of ride-hailing drivers, we surveyed a large sample, covering the vast majority of areas with available ride-hailing services (31 provincial-level administrative regions). The analysis results offer a comprehensive perspective on the smoking problems of ride-hailing drivers. They contribute to the understanding of different socio-economic and working characteristics that affect the smoking status of drivers. The risk factors for smoking behaviour based on the large random sample study can provide real-world evidence for international tobacco control researchers.

Methods

Study design and participants

From September to November 2017, using the platform of ride-hailing companies with 91% market share in China, we distributed questionnaires to drivers’ accounts through the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), which provides functions equivalent to Amazon Mechanical Turk. A total of 9003 questionnaires were assigned, of which 8990 were considered valid, with an effective rate of 99.86%. For large populations of more than 150,000, a sampling ratio of 1%, or approximately 1500 sample sizes, will obtain the correct result [45]. Considering that the full-time ride-hailing drivers investigated in this study belong to a large population, our sample size could achieve ideal accuracy.

Measures

The design of the questionnaire referred to the previous literature on the influence factors of smoking. We also considered the questionnaires of the National Health Service Survey and the National Population Census. The final version passed the demonstration of experts in health management and disease prevention and control. The questionnaire had four parts: sociodemographic characteristics, job characteristics, health-related factors and smoking status. The health-related factors included healthy behaviour, health status and health literacy of three aspects (Table 1).

Quality control

In the process of the questionnaire design, we tested the logic of the questions. We used Cronbach’s PCR coefficient and semi-correlation to test the reliability of the scale. The results showed that the total Cronbach’s p coefficient of the scale was 0.899, and the semi-correlation coefficient was 0.833. Except for age, all questions adopted a closed questionnaire design. The questionnaire could not be submitted until all the questions were finished, and the same account could only fill in the questionnaire once. The data was directly exported from the electronic questionnaire database, avoiding manual input errors. To rule out errors in the filling, we cleaned the data to eliminate invalid questionnaires. Specifically, we excluded those with contradicting answers to different questions. For example, the chronic disease reported by the respondents did not match their age or gender, and the self-reported age did not qualify for the given years in service.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were converted into categorical variables and displayed with numbers and percentages. We analysed the correlation between current smokers and other indicators by conducting a chi-square test. We used binary logistic regression to investigate the mixed effect of the smoking behaviour of drivers. We used the respondents’ smoking status as the dependent variable and the statistically significant correlation factors found in the chi-square test as the independent variables. We also included multiple categorical variables in the model as dummy variables. We considered a two-tailed P-value < 0.05 and ORs with 95% CIs for the significant relationship between the exposure and outcome variables. We conducted all analyses using SPSS software version 22.0.

Results

Characteristics of the drivers

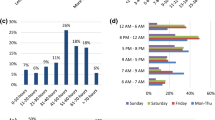

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the respondents. A total of 5133 cases (57.1%) were from the eastern regions, 1812 cases (20.2%) were from the central regions, and 2045 cases (22.7%) were from the western regions with the highest smoking rate (60.1%, P < 0.001). The proportion of male and female drivers was 95.9 and 4.1%, respectively, and the smoking rate of male drivers was significantly higher than that of female drivers (56.7% v 37.6%, P < 0.001). Moreover, 43.8, 31.4 and 24.8% of the drivers were working for < 10 h a day, 10–12 h a day and > 12 h a day. The longer the working hours, the higher the smoking rate (P = 0.005). Those who reported poor physical (P = 0.012) and mental health (P < 0.001) had a higher smoking rate than other drivers. Smoking habits were common amongst drivers who had unhealthy daily habits and behaviours, such as drinking alcohol (P < 0.001), irregular diet (P < 0.001), mainly eating out (P < 0.001), short sleep duration (P < 0.001) and little exercise time (P < 0.001).

The rate of current smoking amongst the respondents was 55.9%. Nearly one-third of smokers smoked in their cars (32.2%, Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis results

The logistic regression results were as follows (Table 4): gender, area of residence, the period of work, drinking status (whether a current drinker), eating habits, the number of days a week of engaging in at least 10 min of moderate or vigorous exercise, level of the initiative to acquire health knowledge and weight status were the relevant influencing factors of current smoking (P ≤ 0.001). Amongst them, current drinker (OR = 1.663, 95% CI [1.526, 1.813]), extremely regular eating habits (OR = 1.370, 95% CI [1.233, 1.523]) and underweight (OR = 1.249, 95% CI [1.001, 1.559]) were the risk factors of current smoking. The drivers in the central (OR = 1.172, 95% CI [1.049, 1.309]) and western regions (OR = 1.330, 95% CI [1.194, 1.480]) had a higher risk of smoking than those in eastern regions, and the smoking risk of the drivers who drove at night (OR = 1.938, 95% CI [1.463, 2.568]) or both daytime and night (OR = 1.287, 95% CI [1.164, 1.424]) or non-fixed time (OR = 1.393, 95% CI [1.223, 1.588]) was greater than that of day-shift drivers. Female (OR = 0.519, 95% CI [0.416, 0.647]), exercising at least three days per week (OR = 0.752, 95% CI [0.646, 0.875]), occasionally (OR = 0.882, 95% CI [0.783, 0.992]) or frequently acquiring health knowledge (OR = 1.393, 95% CI [1.223, 1.588]) and overweight (OR = 0.675, 95% CI [0.591, 0.770]) were protective factors for current smoking.

Discussion

Smoking behaviour of drivers

The prevalence of smoking amongst ride-hailing drivers in our survey was much higher than that of Chinese adults (26.6% [47]). It was consistent with that of taxi drivers in other large surveys across the country [7,8,9]. Many smokers also smoked in cars, forcing passengers to breathe second-hand smoke. This situation poses health risks and not conducive to the construction of urban civilisation.

Sociodemographic characteristics and smoking

Gender had a major influence on the current smoking of online ride-hailing drivers, which was consistent with the smoking pattern in most studies [48,49,50]. Some men see smoking as a sign of masculinity [51], and Chinese society, still influenced by a partly rooted tradition, is tolerant of male smoking but not female smoking [52]. Thus, smoking is more prevalent in men than in women.

Chinese drivers’ smoking behaviour also reflected regional differences. Smoking poses higher risks amongst the drivers in the central and western regions than those in the eastern regions. The Report on the Current Situation of Smoking in China in 2016 [53] showed that the central and western regions and Yunnan Province had the highest proportion of smokers, followed by the eastern coastal areas. The distribution of smoking amongst online taxi-hailing drivers was similar. Given the various reasons, the influence of smoking culture has the most effect. Smoking culture in China has a long history, and it varies from place to place due to vast Chinese territory. Northeast tobacco and Hunan tobacco are typical examples, where the proportion of smokers in China is also at a high level. The central and western regions are also known for their prominent tobacco industries. As a big part of their regional economies, such industries will have an effect to some extent. Finally, the strictness of policies and regulations in different regional areas is varied. The eastern regions are more developed, with a relatively complete smoke-free policy and stricter implementation. Therefore, the proportion of smokers in the eastern regions has been declining compared with the central and western regions in recent years [54].

Unlike day-shift drivers, working at night, working at both daytime and night and working at the non-fixed time were risk factors for drivers to smoke. Some ride-hailing platforms need to ensure a certain amount of time online every day, and due to the uncertainty of the orders, the driver needs to keep an eye on the phone. Full-time ride-hailing drivers tend to work long hours with relatively little freedom. More than half (56.2%, Table 2) of the respondents worked more than 10 h a day, and 71.3% usually drove at night, both daytime and night or an irregular time. Studies have shown that shift work can cause the disorder of human biological rhythm, which harms health. Bad behaviours, such as smoking and drinking, are common amongst shift workers [55], and drivers may use smoking to refresh themselves and relieve fatigue.

Health behaviour and smoking

Our analysis results showed that more exercise could reduce smoking risk, which was consistent with prior findings on the association between physical activity and smoking [56]. Studies have shown that exercise can reduce smoking desire and withdrawal response to smoking cessation and ultimately help people stop smoking [57,58,59]. The mechanism may be that exercise and smoking have similar effects on neurobiological processes, such as increasing the levels of beta-endorphin in smokers, to serve as an alternative reinforcer of smoking [60, 61].

Drivers with extremely irregular eating habits had a higher risk of smoking than those with extremely regular eating habits, which was consistent with the results of Doris Anzengruber et al. [62] on the relationship between smoking and irregular diet. Smoking behaviour was common in individuals with irregular diets and associated with impulsive personality traits in groups with eating disorders, such as overeating.

In the current study, we found that current drinkers had a higher risk of smoking than nondrinkers. Johannes Thrul et al. [63] pointed out that alcohol and tobacco were often used together, and smoking whilst drinking could increase pleasure. Thus, drinking might inhibit successful smoking cessation. For drivers, alcohol will directly damage their health and increase the risk of other health hazards and be one of the main culprits of traffic accidents. In 2011, drunk-driving was included in criminal law in China. Thus, strengthening drivers’ perception of the risks brought by drinking is crucial. Understanding this matter will help them control their drinking behaviour.

Health literacy and smoking

The health awareness of the ride-hailing drivers was weak, which needs to be improved. Nearly half of the drivers sought health knowledge only when they were sick or not feeling well (49.7%, Table 2). Less than one-third often actively acquired health knowledge. Health literacy can promote healthy behaviour in the general population and reduce the risk of addiction to unhealthy behaviours. People with high health literacy will be more aware of the hazards associated with smoking and pay more attention to their health, leading to a low smoking rate. This statement is consistent with the theoretical model of Knowledge, Trust and Practice (KPA) in health education.

Obesity and smoking

More than half of the ride-hailing drivers (53.2%, Table 2) were overweight, much higher than the national average of 42.1% [64]. Some studies have shown that obesity and smoking, both as influencing factors of various diseases, can increase the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases amongst drivers [65, 66]. The relationship between smoking and obesity is extremely complicated. Current studies generally agree that smoking can reduce obesity because smoking suppresses appetite at the cellular level and reduces energy intake and consumption [67]. Other studies suggest that obese people may lose weight by starting to smoke. Consequently, it may increase nicotine dependence and influence smoking intensity [68]. However, through Mendel randomised studies with large samples, Carreras-Torres et al. [69] found that the increase in BMI had a high correlation with current smoking status and smoking intensity. Such a high association may be caused by clusters of single nucleotide polymorphisms in neuronal pathways, suggesting that addictive behaviours, such as nicotine addiction, and high energy intake may have a common biological basis. Thus, the causal relationship between obesity and smoking requires further investigations.

Weight may also temporarily increase in the process of quitting smoking. Thus, some smokers, especially women, do not try to or fail to give up smoking [70].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, numerous complex factors affect smoking behaviour. We could only discuss the main factors by combining our literature review with the characteristics of the respondents. Thus, neglecting some possible influencing factors is difficult to avoid. Secondly, given the limitations of cross-sectional studies, we could not determine causal relationships between certain variables and smoking outcomes. We only inferred such relationships from similar studies. Thirdly, we adopted an electronic self-filling questionnaire. Such a method could not ensure the authenticity and independent completion of the respondents. Accordingly, we guaranteed the quality of the questionnaire through a standardised questionnaire option design and online car-hailing platform system monitoring.

Conclusion

Our survey showed that the smoking rate of online ride-hailing drivers was high, demanding immediate action. Policymakers and company managers can implement tobacco control amongst online ride-hailing drivers from two aspects. Firstly, online ride-hailing drivers should be encouraged to stop or limit smoking. On the one hand, they should undergo psychological intervention, especially the male drivers in the central and western regions. Company managers should consider adding ‘No Smoking’ signs in the car and setting up health promotion columns on the driver and passenger interface of online ride-hailing apps. Such materials can remind and inform the drivers about the health risks of smoking. In this way, drivers can stop relying on misleading information available online. On the other hand, behavioural intervention should guide drivers to exercise more, eat a balanced meal and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Alcohol restriction intervention and weight intervention should also assist in tobacco cessation or restriction. Secondly, authorities in the ride-hailing industry can set up convenient channels for complaints as part of the credit rating system amongst drivers and riders.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xiao Y. Analysis of the influencing factors of the unsafe driving behaviors of online car-hailing drivers in China. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231175.

Wang YX, Chen JY, Xu N, Li W, Yu Q, Song X. GPS data in urban online Car-hailing: simulation on optimization and prediction in reducing void cruising distance. Math Probl Eng. 2020;2020:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6890601.

Li X, Zhang Z. Research on Local Government Governance and Enterprise Social Responsibility Behaviors under the Perspective of Cournot Duopoly Competition: Analyzing Taxi Companies and Online Car-Hailing Service Companies. Math Probl Eng. 2018;2018(PT.9):5794232.1–12.

People's Daily. The Didi cooperation network covers thousands of cities around the world. 2017. Available: http://it.people.com.cn/n1/2017/0815/c1009-29470482.html. Accessed 25 May 2019.

iiMedia Research. 2017-2018 China Network Car Industry Research Special Report. 2018. Available: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/61053.html. Accessed 20 May 2019.

China Internet Network Information Center. Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. 2020. Available: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202009/t20200929_71257.htm. Accessed 20 Aug 2020.

Pan LL, Duan YF, Lai JQ, et al. Survey on life style and health condition of taxi drivers in Beijing. Chin J Health Educ. 2012;28(02):114–7.

Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, Lin DQ, et al. Investigation on Smoking and Drinking in 81547 Drivers in Guangzhou. China Public Health. 2001;(06):63–5.

Chen LQ, Zhou Q, Gao M. Survey on the prevalence of cigarette smoking among professional drivers in Linyi City. Chin J Health Educ. 2007;(07):532–4.

Chai JX, Cao Y, Wan GF, et al. Investigation on tobacco hazard and tobacco control knowledge among taxi drivers in Beijing. Chin J Prevent Control Chronic Dis. 2019;27(04):296–8.

Zhong. Drivers should not smoke when they are tired. Occupation and Health. 1995;(02):8.

Mangiaracina G, Palumbo L. Smoking while Driving and its Consequences on Road Safety. Ann Ig. 2007;19(3):253–67.

Ravara SB, Castelo-Branco M, Aguiar P, et al. Compliance and enforcement of a partial smoking ban in Lisbon taxis: an exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:134.

Chung W, Lim S, Lee S. Factors influencing gender differences in smoking and their separate contributions: evidence from South Korea. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1966–73.

Li S, Kwon SC, Weerasinghe I, et al. Smoking among Asian Americans: acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York City. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:18S–28S.

Levin KA, Dundas R, Miller M, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in adolescent smoking: a multilevel cross-sectional study of 15 year olds in Scotland. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107(100):162–70.

Li H, Zhou Y, Li S, et al. The relationship between nicotine dependence and age among current smokers. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:495–500.

Ramsey MW, Chen-Sankey JC, Reese-Smith J, et al. Association between marital status and cigarette smoking: Variation by race and ethnicity. Prev Med. 2019;119:48–51.

Macy JT, Chassin L, Presson CC. Predictors of health behaviors after the economic downturn: A longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2013;89:8–15.

Khlat M, Pampel F, Bricard D, et al. Disadvantaged social groups and the cigarette epidemic: limits of the diffusion of innovations vision. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1230.

Goel, R. K. Economic stress and cigarette smoking: Evidence from the United States[J]. Econ Model. 2014;40:284–9.

de Leeuw RN, Verhagen M, de Wit C, et al. One cigarette for you and one for me: Children of smoking and non-smoking parents during pretend play. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):344–8.

Thomeer MB, Hernandez E, Umberson D, et al. Influence of Social Connections on Smoking Behavior across the Life Course. Adv Life Course Res. 2019;42.

Kim SS, Son H, Nam KA. Personal factors influencing Korean American men's smoking behavior: addiction, health, and age. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2005;19(1):35–41.

Tsai J, Ford ES, Li C, et al. Multiple healthy behaviors and optimal self-rated health: Findings from the 2007 behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. Prev Med. 2010;51:268–74.

Forman-Hoffman VL, Hedden SL, Glasheen C, et al. The role of mental illness on cigarette dependence and successful quitting in a nationally representative, household-based sample of U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(7).

Prochaska JJ, Das S, Young-Wolff KC. Smoking, Mental Illness, and Public Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:165–85.

Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Firth J, et al. Association between depression and smoking: A global perspective from 48 low- and middle-income countries. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:142–9.

Gurung MS, Pelzom D, Dorji T, et al. Current tobacco use and its associated factors among adults in a country with comprehensive ban on tobacco: findings from the nationally representative STEPS survey. Popul Health Metr. 2016;14:28.

Coleman SRM, Gaalema DE, Nighbor TD, et al. Current cigarette smoking among U.S. college graduates. Prev Med. 2019;128:105853.

Higgins ST, Kurti AN, Redner R, et al. Co-occurring risk factors for current cigarette smoking in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Prev Med. 2016;92:110–7.

Pryce R. The effect of the United Kingdom smoking ban on alcohol spending: Evidence from the Living Costs and Food Survey. Health Policy. 2019;123(10):936–40.

Pagano A, Gubner NR, Le T, et al. Differences in tobacco use prevalence, behaviors, and cessation services by race/ethnicity: A survey of persons in addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;94:9–17.

Chen GB, Zou XN, Chen YL, et al. Investigation of Nicotine Dependence and Its Influencing Factors of Smokers in China. Med Society. 2013;26(12):1–4.

Xie J. A Study on the relationship between smoking behavior and psychological stress of urban residents. Master Thesis, Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China. 2009;28(3):229–32.

Hu WB, Zhang T, Zhang XH, et al. Smoking status and associated factors among residents aged 18-69 years old in Kunshan City of Jiangsu Province. Chin J Health Educ. 2018;34(05):395–9.

Li XF, Tian GQ, Zhu QB. The impacts of social-economic factors on rural residents smoking of four provinces. Chin J Health Educ. 2016;32(09):771–4.

Brown JM, Anderson Goodell EM, Williams J, et al. Socioecological Risk and Protective Factors for Smoking Among Active Duty U.S. Mil Med. 2018;183(7-8):e231–9.

Mbarek H, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Jan Hottenga J, et al. Association Between rs1051730 and Smoking During Pregnancy in Dutch Women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(6):835–40.

Ye SY, Chen ZY, Qiu YB. Analysis of smoking status and influencing factors among manufacturing workers in Baoan District, Shenzhen city. China Health Ind. 2018;15(34):184–6.

Norman GJ, Ribisl KM, Howard-Pitney B, et al. Smoking bans in the home and car: Do those who really need them have them? Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):581–9.

Martin J, George R, Andrews K, et al. Observed smoking in cars: a method and differences by socioeconomic area. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):409–11.

Jain NB, Hart JE, Smith TJ, et al. Smoking behavior in trucking industry workers. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(12):1013–20.

Ozoh OB, Akanbi MO, Amadi CE, et al. The prevalence of and factors associated with tobacco smoking behavior among long-distance drivers in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(3):886–95.

Shao ZQ. Method for determining sample size in sampling survey. Statistics & Decision. 2012;(22):12–4.

Wang BY. Study on structural characteristics and temporal and spatial differences of. Available: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/61053.html. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The results of the 2018 China Adult Tobacco Survey were released- The smoking rate among people aged 15 and above in China is on the decline. 2019. Available: http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/sthd_3844/slhd_4156/201905/t20190530_202932.html. Accessed 15 Oct 2019.

Ferguson SG, Frandsen M, Dunbar MS, et al. Gender and stimulus control of smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(4):431–7.

Amos A, Greaves L, Nichter M, et al. Women and tobacco: a call for including gender in tobacco control research, policy and practice. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):236–43.

Curto A, Martínez-Sánchez JM, Fernández E. Tobacco consumption and secondhand smoke exposure in vehicles: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000418.

Kodriati N, Pursell L, Hayati EN. A scoping review of men, masculinities, and smoking behavior: The importance of settings. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(sup3):1589763.

Fang YH, He YN, Bai GY, et al. Prevalence of alcohol drinking and influencing factors in female adults in China, 2010-2012. Chin J Epidemiol. 2018;39(11):1432–7.

Shuo SS. A report on smoking status and anti-smoking attitudes of Chinese people in 2016. 2016. Available: http://www.catcprc.org.cn/index.aspx?menuid=21&type=articleinfo&lanmuid=175&infoid=7626&language=cn. Accessed 15 Nov 2019.

Chen YH. Epidemiological investigation of lifestyle and health status of shift workers. Master Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China. 2011.

Tosun NL, Allen SS, Eberly LE, et al, Association of exercise with smoking-related symptomatology, smoking behavior and impulsivity in men and women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:29–37.

Ussher MH, Taylor A, Faulkner G. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD002295.

Vaughan Roberts, Ralph Maddison, Caroline Simpson, et al, The acute effects of exercise on cigarette cravings, withdrawal symptoms, affect, and smoking behaviour: systematic review update and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacol. 2012;222(1):1–15.

Stefanie De Jesus, Harry Prapavessis. Smoking behaviour and sensations during the pre-quit period of an exercise-aided smoking cessation intervention. Addict Behav. 2018;81:143–9.

Julie A. Morgan, Gaurav Singhal, Frances Corrigan, et al, Ceasing exercise induces depression-like, anxiety-like, and impaired cognitive-like behaviours and altered hippocampal gene expression. Brain Res Bull. 2019;148:118-30.

Donrawee Leelarungrayub, Sainatee Pratanaphon, et al, Vernonia cinerea Less. supplementation and strenuous exercise reduce smoking rate: relation to oxidative stress status and beta-endorphin release in active smokers. J Int Society Sports Nutr. 2010;7(1).

Rod K. Dishman, Patrick J. O'Connor, Lessons in exercise neurobiology: The case of endorphins. MENT HEALTH PHYS ACT. 2009;2(1):4-9.

Anzengruber D, Klump KL, Thornton L, et al. Smoking in eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2006;7(4):291-9.

Thrul J, Gubner NR, Tice CL, et al. Young adults report increased pleasure from using e-cigarettes and smoking tobacco cigarettes when drinking alcohol. Addict Behav. 2019;93:135-40.

Zhan WH. New progress in the application of intervention measures in adult obese patients. China Practical Medcine. 2019;14(29):194-5.

Martin WP, Sharif F, Flaherty G. Lifestyle risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetic risk in a sedentary occupational group: the Galway taxi driver study. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185(2):403-12.

Gany F, Bari S, Gill P, et al. Step On It! Workplace Cardiovascular Risk Assessment of New York City Yellow Taxi Drivers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(1):118-34.

Chen H, Saad S, Sandow SL, et al. Cigarette smoking and brain regulation of energy homeostasis. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:147.

Rupprecht LE, Donny EC, Sved AF. Obese Smokers as a Potential Subpopulation of Risk in Tobacco Reduction Policy. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(3):289-94.

Carreras-Torres R, Johansson M, Haycock PC, et al. Role of obesity in smoking behaviour: Mendelian randomisation study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2018;361:k1767.

Dare S, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Correction: Relationship between Smoking and Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of 499,504 Middle-Aged Adults in the UK General Population. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172076.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yue Bai, Yamin Bai, Xingming Li and Ling Hu for their support of survey design and questionnaire.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71403178) and the research project of the Health Development Research Center of the Health and Family Planning Commission and the Red Cross Society of China (04279).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.C and N.N.W conceived and designed the study. X.F.G, T.T.L, L.R.X, and B.P. collected the data. X.L.C, N.N.W and X.F.G analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. T.T.L, L.R.X, B.P., and Q.Y.L. provided statistical analysis support. All authors supplied critical revisions to the manuscript and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was implemented in November 2016. According to the Regulation on Ethical Review Methods Relating to Human Biomedical Research (Trial Implementation) then in effected, issued by National Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China (Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/bgt/pw10702/200703/02ff483b38e947769adc271b581e3451.shtml), ethical review includes the following two aspects: (1) Research activities are adopted on human physiology, pathology, and diseases of the diagnosis, treatment and prevention, by using of modern physics, chemistry and biological methods in the human body. (2) A medical technology formed by biomedical research or their products experimentally applied on the human body. The research objects were beyond that scope. Furthermore, there was no interventional measures on the subjects in study. Therefore, there is no ethical approval during the study. We discussed the study with ethics committee of the Capital Medical University recently, and obtain confirmation from the committee that the study would not have required ethics approval. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The data were collected by issuing electronic questionnaires, which were not face-to-face and filled out voluntarily by drivers with informed consent, and the questionnaires could not be traced to individual drivers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

A questionnaire on the health status and behavior of online ride-hailing drivers in China.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Gu, X., Li, T. et al. Factors influencing smoking behaviour of online ride-hailing drivers in China: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 21, 1326 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11366-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11366-8