Abstract

Background

Adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa are a vulnerable group at the intersection of poverty and health disparities. The family is a vital microsystem that provides financial and emotional support to achieve optimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence. In this study, we explore the association between family factors and ART adherence self-efficacy, a significant psychological concept playing a critical role in ART adherence.

Methods

Data from an NIH-funded study called Suubi + Adherence, an economic empowerment intervention for HIV positive adolescents (average age = 12.4 years) in southern Uganda was analyzed. We conducted multilevel regression analyses to explore the protective family factors, measured by family cohesion, child-caregiver communication and perceived child-caregiver support, associated with ART adherence self-efficacy.

Results

The average age was 12.4 years and 56.4% of participants were female. The average household size was 5.7 people, with 2.3 children> 18 years. Controlling for sociodemographic and household characteristics, family cohesion (β = 0.397, p = 0.000) and child-caregiver communication (β = 0.118, p = 0.026) were significantly associated with adherence self-efficacy to ART.

Conclusion

Findings point to the need to strengthen family cohesion and communication within families if we are to enhance adherence self-efficacy among adolescents living with HIV.

Trial registration

This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01790373) on 13 February 2013.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Uganda is a low-income country with one of the highest prevalence rates of HIV (7.3% among 15–49-year old) worldwide [1]. It is estimated that 130,000 children under the age of 14 in Uganda were living with HIV in 2016 [2]. Although the development of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has made HIV a manageable chronic illness, [3] adherence to ART needs to reach 95% in order to reach the desired treatment outcomes [4, 5]. However, research shows that ART adherence level in Uganda is still low among people living with HIV (PLWH), with only 66% reporting the desired adherence outcomes [6]. Moreover, in rural areas, adherence rates are much lower, with only 55% adhering to their medication [7]. Furthermore, the ART coverage for children in Uganda is estimated to be only 47% of the target population [8]. Yet, low ART adherence can result in increased viral duplication, rapid disease progression, reduced life quality, and even premature mortality [9]. Therefore, suboptimal ART adherence among children in Uganda is an urgent health issue that needs to be addressed. Against this backdrop, this study examines family factors that impact ART adherence self-efficacy among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents (aged 10 to 16 years) in southern Uganda so that more targeted interventions can be put in place to improve ART adherence.

Medication adherence and self-efficacy

In the context of HIV, ART adherence is defined as the degree to which an individual adheres to taking the prescribed antiretroviral drugs [4]. Observable ART adherence levels depend on a range of factors, [10] including self-efficacy i.e. the person’s perception of their own ability to accomplish a behavioral task, [11] which influences a person’s development or maintenance of a health behavior at the affective, cognitive and motivational levels [12]. More specifically, adherence self-efficacy –defined as the confidence in one’s ability to adhere to treatment plans, has been documented as an important predictor of medication adherence in the treatment of HIV and other medical conditions [13]. For example, an individual who feels able to successfully fulfill medication regimes as prescribed, in addition to following a specified diet, as well as executing recommended lifestyle changes, [14] will be more likely to achieve positive health outcomes. Moreover, individuals tend to be more motivated if they perceive that their actions can be completed [15]. Indeed, adherence self-efficacy has been linked to positive outcomes among patients with hypertension, [16] asthma, [17, 18] diabetes [19, 20] pain management [21] and depression [22].

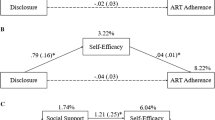

Among PLWH, self-efficacy has been corelated with adherence outcomes [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. For example, a meta-analysis examining the predictors and correlates of ART adherence found that adherence self-efficacy was positively associated with the initiation and maintenance of ART adherence [23]. In another study in South Africa, a strong association between self-efficacy and ART adherence was found in the nonadherent participants, explaining 9.8% of the variance [24]. In the United States and Puerto Rico, Nokes and colleagues [25] found adherence self-efficacy to be a robust predictor of ART adherence and a mediator between environmental influences and cognitive or personal factors. However, few of these studies have been conducted in SSA, and none have focused on children and adolescents living with HIV [24]. Yet, for children who depend on their caregivers to meet their adherence expectations, it is important to examine and understand their cognitive and motivational influences affecting medication adherence, including self-efficacy.

Social support and adherence

Several studies have documented the role of social support, especially from family members in influencing adherence outcomes [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. For example, a meta-analysis of studies examining social support and patient adherence to medication showed that ART adherence was 1.74 times higher in patients from cohesive families and 1.53 times lower in patients from families experiencing conflict [30]. In Uganda, family cohesion and social support from caregivers/family were associated with self-reported adherence to ART among HIV-infected adolescents [31]. In another study examining the benefits of family and social relationships for health and mental health of PLWH, family functioning significantly contributed to ART adherence and quality of life [32]. Thus, strengthening positive family support and minimizing negative family interactions are crucial for increasing adherence rates [33].

Despite the unique developmental needs of children and adolescents, few studies have specifically focused on family systems among HIV-infected children and adolescents in SSA [31, 34, 35]. Moreover, these studies do not explicitly explore the relationship between family support and adherence self-efficacy –two factors that are critical to HIV management and adherence to treatment protocols among PLWH, including children and adolescents [36]. Thus, to bridge this gap, this study examines whether family factors, such as family cohesion, child–caregiver communication, and perceived child-caregiver support, are associated with ART adherence self-efficacy among HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda. We hypothesize that these family factors will be positively associated with positive ART adherence self-efficacy levels over time.

Methods

Study sample and context

This study utilized data from the Suubi+Adherence study, a longitudinal randomized clinical trial funded by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (Grant # R01HD074949). The Suubi+Adherence study examined an innovative family-based economic empowerment intervention on ART adherence among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda, a region heavily affected by HIV/AIDS. Uganda has a national HIV prevalence rate of 7.3% among adults aged 15–49, with higher prevalence rates of 12% in the southern region where the study was implemented [1]. The Suubi+Adherence study followed 702 HIV-positive adolescents (306 boys and 396 girls) between 2012 and 2017. Participants were identified and recruited from health clinics in the greater Masaka region associated with Reach the Youth (RTY) Uganda and the Masaka Diocese (our collaborating partners). All health clinics were accredited by the Uganda Ministry of Health to provide ART to all adolescents living with HIV in the region. The inclusion criteria for these adolescents were: 1) 10–16 years old, 2) HIV-positive and know their HIV status, 3) prescribed antiretroviral therapy, 4) living within a family, not an institution, and 5) enrolled in one of the 39 health centers or clinics in Rakai, Masaka, Lwengo, Lyantonde, Bukomasimbi, and Kalungu Districts in the study area. Detailed information on participants recruitment and selection process, as well as the study intervention is described in the study protocol and in our other publications [37, 38].

Data collection

Data were collected using a 90-min interviewer administered survey at baseline, 12, 24, 36 and 48-months post baseline. Survey instruments and all research related documents (including consent/assent forms) were translated into Luganda – the most widely spoken language in the study region – and back translated into English to ensure accuracy. This process was overseen by certified language experts at the Makerere University in Uganda. All interviewers completed the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) certificate and NIH certificate for protection of research participants, prior to participant contact. In addition, the study team received training on Good Clinical Practices (GCP) so that sensitive research activities were handled appropriately. Details on data protection are provided in the study protocol [37].

Measures

The dependent variable in this study is adherence self-efficacy, assessed by the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale [13]. The scale measures adolescents’ confidence in integrating prescribed ART plan into their routine life and maintaining optimal adherence levels. The scale was previously tested among people living with HIV in the southern region of Uganda, with a high reliability score (Cronbach’s alpha = .92) [39]. There are nine integration questions, such as “In the past month, how confident have you been that you can stick to your treatment plan even when side effects begin to interference with daily activities?” and three perseverance questions, such as “In the past month, how confident have you been that you can continue with the treatment plan your physician prescribed even if your T-cells drop significantly in the next three months?” The rating range is between 1 and 10, with a higher rating representing higher levels of adherence self-efficacy. The scale has a high reliability (alpha = 0.91).

Family support factors were measured by three indicators: 1) family cohesion, 2) perceived child–caregiver support, and 3) child-caregiver communication, all adapted from the Family Environment Scale, [40] and the Family Assessment Measure [41]. All these measures were tested in our previous studies in Uganda among children affected by HIV/AIDS [31, 42,43,44].

Family cohesion was assessed by an 8-item scale that measures the degree of commitment, help and support family members provide for one another. Participants were asked to rate how often each item occur in their family, on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘never’ and 5 = ‘always’). Sample items include: “Family members ask each other for help before asking non-family members.” and “Family members like to spend free time with each other.” The scale had a strong internal consistency (alpha = 0.79). Summary mean scores were created with higher scores indicating high levels of family cohesion.

The perceived child-caregiver support scale assesses social support on two dimensions: (1) acceptance and warmth – the extent to which the child perceives the caregiver as involved in their life; and (2) psychological autonomy – the extent to which the caregiver employs a non-coercive, democratic discipline and encourages the child to express individuality within the family. Participants were asked to rate the adults they live with, on each of the 18 items (range: 18–70, alpha = 0.76), on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘never’ and 5 = ‘always’). Sample items include: “Child can count on parent/guardian to help in case of a problem,” and “Parent/guardian explains why they want the child to do something.” Summary mean scores were created, with higher scores indicating high levels of perceived child-caregiver support.

The child-caregiver communication scale assesses discussions between the child and the caregiver on 12 items related to issues such as puberty, cigarette smoking, sexual risk taking, puberty, HIV/AIDS, educational plans, etc. Participants were asked to indicate how often they discussed the specific topics with their caregivers, on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘never’ and 5 = ‘always’). Summary mean scores were created with higher scores indicating high levels of child-caregiver communication (range: 10–50, alpha = 0.79).

Control variables included in the analysis were: participants’ gender, age, total number of people in the household, total number of children in the household, primary caregiver (i.e. biological parent, grandparents, and others such as uncle, aunt, brother sister, etc.), school enrollment (whether enrolled in school or not), HIV disclosure status to other individuals other than the primary caregiver, medication regimen and study condition (whether assigned to the treatment or control condition).

Analysis procedures

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 15. Bivariate analyses were conducted on baseline sociodemographic and household characteristics, adherence self-efficacy and family support factors. Baseline results were compared between the control and treatment conditions (Table 1). Multilevel analysis was used to examine the relationship between adherence self-efficacy and family support factors over time based on the formula:

where β0 is intercept, X2ij through Xpij are covariates and ξij is a residual.

The models were built with -mixed command using vce (robust) option in STATA, that has the advantage that the estimated standard errors are valid even if the level-1 errors are heteroskedastic or autocorrelated [45]. This method was used to study adherence self-efficacy over time (time - level 1), person – level 2 characteristics (family support factors) that influence initial adherence self-efficacy (intercept) and change over time (slope). This approach did not require individuals to have equal numbers of measures and can handle both time invariant and time-varying covariates.

First, the analysis started with building unconditional three-level model to determine between-person and within-person variability in adherence self-efficacy scores (Table 2). Second, level-1 family factor variables (cohesion, communication and support) were added to the unconditional model (Table 3). Like for many other psychological constructs that lack a clearly interpretable or meaningful zero-point, [46] we used Centered Within Cluster (within subject) variables to establish a useful zero point [47]. To accommodate possible endogenous time-varying covariates that are correlated with the random-intercept ζj, the model was fitted allowing for different within and between effects for time-varying covariates by including both subject-mean centered and the occasion-specific deviations from the subject means as the subject-mean centered covariates are uncorrelated with ζj by construction, and the corresponding coefficients could be consistently estimated [45]. Finally, we fitted the model with all the control variables (Table 4). Statistical significance was determined at the 5% level.

Results

Baseline sociodemographic and household characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The average age was 12.4 years and the majority of participants were female (56.4%). About 38% of participants identified as single orphans, meaning they had one surviving biological parent, 24.4% were non-orphans. The majority of adolescents (46.3%) identified a surviving biological parent as the primary caregiver. Participants lived in household with an average of 5.7 people and 2.3 children under the age of 18. At baseline, 87.3% of participants were enrolled in school. In terms of HIV disclosure, 32.3% of adolescents reported that they never keep their HIV status a secret. However, about the same number of adolescents (32.2%) reported that they always keep their HIV a secret. The majority of participants (53.7%) had to take their HIV medication at least twice a day. In terms of family support factors, participants reported moderate levels of communication with their caregivers (mean = 21.1, SD = 7.6), and perceived child-caregiver support (mean = 46.5, SD = 10.3). Higher levels of family cohesion were reported, with mean score of 31.8 (SD = 6.7). Adolescents reported higher levels of adherence self-efficacy, with an average score of 94.28 (SD = 23.25). No statistically significant differences were observed between the control and treatment conditions.

Table 2 presents results from a multilevel unconditional model conducted to determine between-person and within-person variability in adherence self-efficacy scores. The variance in adherence self-efficacy over time for each child was 391.7 (s2 = 391.7), explaining 83% of total variance. The variance of the true self-efficacy averaged over time was 79.3(16.7% of variance), while variability of clinic means around the grand mean was only 2.75 (0.6% of the variance). The intraclass correlation for individual level (level 2) was 0.173, and - 0.006 at the clinic level (level 3). The likelihood ratio test indicated that there was evidence that using a random intercept model could explain the variance in adherence self-efficacy even in the absence of any covariates (LR test vs. linear model: χ2 (1) = 153.04, p = 0.000). Further analysis showed that there was no significant difference between 3-level and 2-level models (LR χ2 (1) =1.65, p = 0.198), thus analysis was continued with exploring 2-level models.

Table 3 presents results from the multilevel model with socio-demographic and household characteristics. Participants’ age was statistically associated with adherence self-efficacy (β = 0.835, p = 0.000). In addition, HIV status disclosure, whether sometimes (β = 3.16, p = 0.001) or always (β = 5.22, p = 0.000), was also associated with adherence self-efficacy. Group assignment (whether control or treatment condition) was not significant (β = − 0.877, p = 0.428). The overall model was statistically significant (F (16, 702) = 84.2, p = 0.000). The variability of self-efficacy over time for each child slightly decreased to 389.8, from 391.1 (Table 2) and variance of the true self-efficacy averaged over time also slightly decreased to 62.7 from 64.3 (Table 2).

Table 4 presents results from the full multilevel analysis models conducted to determine the association between family factors and adherence self-efficacy, controlling for sociodemographic and household characteristics. Family cohesion (β = 0.397, p = 0.000) and child–caregiver communication (β = 0.118, p = 0.026) were both positively associated with adherence self-efficacy. Perceived child-caregiver support was not statistically significant (β = − 0.087, p = 056). The entire model was statistically significant (F (19, 702) = 177.29, p = 0.000).

In comparison to the previous model with socio-demographic and household characteristics only (Table 3), the variability in adherence self-efficacy changed even more. Specifically, over time, self-efficacy for each child decreased even more to 384.3while variance of the true self-efficacy averaged over time decreased to 53.9 indicating that family factors can play significant role to define adolescents’ adherence self-efficacy.

Discussion

This study examined the family factors (family cohesion, child-caregiver communication and perceived child-caregiver support) associated with ART adherence self-efficacy among HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda. Findings from our study indicate that family cohesion and communication represent emotional support from family members towards HIV-infected adolescents and is felt by adolescents through daily communication and care expressed by family members. Although adolescence involves developing independence as a developmental stage, the supportive relationships and connections with family and caregivers continue to be protective factors. Specifically, for HIV-infected adolescents, family is the primary source of financial, physical, and emotional support. Moreover, most adolescents rely on their family members, especially caregivers, to access HIV care and help administer medication regimes [48, 49]. As such, family members’ assistance in helping with HIV-related concerns or problems encountered by adolescents can contribute to improving adolescents’ self-efficacy in integrating treatment plans into their daily routines. This finding underscores the protective role of family and provides further evidence for transitioning from individual-based to family-focused health interventions.

Orphanhood status was not associated with adherence self-efficacy. This finding somewhat deviates from past research in other sub-Saharan African countries, which showed that orphaned children were more likely to be ART nonadherent [50, 51]. One possible explanation for this finding could be that given that all adolescents included in this study were living within a family (either with a surviving biological parent or another relative), they were already being supported by family members to access and adhere to their medication, regardless of their biological relatedness. This finding also points to the fact that extended family networks in Uganda are very supportive, which is in line with the cultural norms where the extended family is expected to assume caregiving responsibilities following parental death [42].

Lastly, this study substantiates for the reasonable application of adherence self-efficacy concept and social cognitive theory in ART adherence. The study findings respond well to the reciprocal determinism of social cognitive theory and highlight family cohesion and child-caregiver communication as significant environments for improving ART adherence among HIV-infected adolescents in low-resource communities.

Even with these findings, a few limitations are worth pointing out. With a general aim to explore the outcomes of the Suubi+Adherence study, this study examined adherence self-efficacy rather than participants’ ART adherence. Theoretically, adherence self-efficacy is an important determinant of ART adherence behavior, however, it may not reflect the actual behavioral outcome [52]. In addition, family is an emotional unit that profoundly influences its members’ thoughts and actions, but the dynamics between individuals and their family systems are complicated. Although we examined family cohesion and child–caregiver relationship in this study, further research using systems thinking to demonstrate how the Suubi+Adherence project can contribute to adherence self-efficacy improvement through enhancing protective functions of family is needed.

Conclusion

Study findings underscore family as a microsystem for HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda, that provides both tangible and emotional support to enhance adherence self-efficacy. Family cohesion, a composite concept representing family closeness and functioning, as well as communication, are both positively associated with adherence self-efficacy. Hence, our findings provide further evidence to consider including families—biological and extended—and targeting family cohesion in interventions aiming at increasing ART adherence among HIV-infected adolescents, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- PLWH:

-

People living with HIV

References

Uganda AIDS Commission. Uganda HIV/AIDS country progress report, July 2016–2017. 2017. Accessed July 5th, 2019 from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/UGA_2018_countryreport.pdf.

World Bank. Children (0-14) living with HIV data. 2018. Accessed July 5th, 2019 from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.HIV.0014?locations=UG.

Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):49–62.

Lima VD, Harrigan R, Murray M, Moore DM, Wood E, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Differential impact of adherence on long-term treatment response among naive HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22(17):2371–80.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21.

Byakika-Tusiime J, Oyugi JH, Tumwikirize WA, Katabira ET, Mugyenyi PN, Bangsberg DR. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy in HIV+ Ugandan patients purchasing therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(1):38–41.

Scheibe FJ, Waiswa P, Kadobera D, Müller O, Ekström AM, Sarker M, Neuhann HF. Effective coverage for antiretroviral therapy in a Ugandan district with a decentralized model of care. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69433.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2017. Accessed July 5th , 2019 from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf.

Wools-Kaloustian K, Kimaiyo S, Diero L, Siika A, Sidle J, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Viability and effectiveness of large-scale HIV treatment initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa: experience from western Kenya. AIDS. 2006;20(1):41–8.

Heestermans T, Browne JL, Aitken SC, Vervoort SC, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(4):1–13.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. 1st ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997.

Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educ Psychol. 1993;28(2):117–48.

Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med. 2007;30(5):359–70.

Sabaté E, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Connolly FR, Aitken LM, Tower M. An integrative review of self-efficacy and patient recovery post-acute injury. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(4):714–28.

Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME. Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(6):520–9.

Campbell TS, Lavoie KL, Bacon SL, Scharf D, Aboussafy D, Ditto B. Asthma self-efficacy, high frequency heart rate variability, and airflow obstruction during negative affect in daily life. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;62(1):109–14.

Ngamvitroj A, Kang DH. Effects of self-efficacy, social support and knowledge on adherence to PEFR self-monitoring among adults with asthma: a prospective repeated measures study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(6):882–92.

Gerber BS, Pagcatipunan M, Smith EV Jr, Basu SS, Lawless KA, Smolin LI, Berbaum ML, Brodsky IG, Eiser AR. The assessment of diabetes knowledge and self-efficacy in a diverse population using Rasch measurement. J Appl Meas. 2006;7(1):55–73.

Gleeson-Kreig JM. Self-monitoring of physical activity. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32(1):69–77.

Gard G, Rivano M, Grahn B. Development and reliability of the motivation for change questionnaire. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(17):967–76.

Tonge B, King N, Klimkeit E, Melvin G, Heyne D, Gordon M. The self-efficacy questionnaire for depression in adolescents (SEQ-DA). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;14(7):357–63.

Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Richter C, Sprangers MA, Nieuwkerk PT. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):142.

Adefolalu A, Nkosi Z, Olorunju S, Masemola P. Self-efficacy, medication beliefs and adherence to antiretroviral therapy by patients attending a health facility in Pretoria. S Afr Fam Pract. 2014;56(5):281–5.

Nokes K, Johnson MO, Webel A, Rose CD, Phillips JC, Sullivan K, Tyer-Viola L, Rivero-Méndez M, Nicholas P, Kemppainen J, Sefcik E. Focus on increasing treatment self-efficacy to improve human immunodeficiency virus treatment adherence. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(4):403–10.

Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):124.

Gifford AL, Bormann JE, Shively MJ, Wright BC, Richman DD, Bozzette SA. Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(5):386–95.

Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E, Gore-Felton C, Goldsten RB, Wolfe H, Lightfoot M, Chesney MA. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the healthy living project. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17(12):645–56.

Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, Vella S, Robbins GK. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(2):141–50.

DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207.

Damulira C, Mukasa MN, Byansi W, Nabunya P, Kivumbi A, Namatovu P, Namuwonge F, Dvalishvili D, Sensoy Bahar O, Ssewamala FM. Examining the relationship of social support and family cohesion on ART adherence among HIV-positive adolescents in southern Uganda: baseline findings. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2019;14(2):181–90.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Stein JA, Jiraphongsa C, Khumtong S, Lee SJ, Li L. Benefits of family and social relationships for Thai parents living with HIV. Prev Sci. 2010;11(3):298–307.

Poudel KC, Buchanan DR, Amiya RM, Poudel-Tandukar K. Perceived family support and antiretroviral adherence in HIV-positive individuals: results from a community-based positive living with HIV study. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2015;36(1):71–91.

Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11):1035–41.

Inzaule SC, Hamers RL, Kityo C, de Wit TF, Roura M. Long-term antiretroviral treatment adherence in HIV-infected adolescents and adults in Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0167492.

Martos-Méndez MJ. Self-efficacy and adherence to treatment: the mediating effects of social support. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues. 2015;7(2):19–29.

Ssewamala FM, Byansi W, Bahar OS, Nabunya P, Neilands TB, Mellins C, McKay M, Namuwonge F, Mukasa M, Makumbi FE, Nakigozi G. Suubi+ adherence study protocol: a family economic empowerment intervention addressing HIV treatment adherence for perinatally infected adolescents. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;1(16):100463.

Bermudez LG, Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Lu L, Jennings L, Nakigozi G, Mellins CA, McKay M, Mukasa M. Does economic strengthening improve viral suppression among adolescents living with HIV? Results from a cluster randomized trial in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(11):3763–72.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Musisi S, Katabira E, Nachega J, Bass J. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive disorders in an HIV+ rural patient population in southern Uganda. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):160–7.

Moos RH, Moos BS. Family environment scale manual. Redwood City: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1994.

Skinner HA, Steinhauer PD, Santa-Barbara J. The family assessment measure. Can J Community Ment Health. 2009;2(2):91–103.

Karimli L, Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L. Extended families and perceived caregiver support to AIDS orphans in Rakai district of Uganda. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(7):1351–8.

Osuji HL, Nabunya P, Byansi W, Parchment TM, Ssewamala F, McKay MM, Huang KY. Social support and school outcomes of adolescents orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS living in South Western Uganda. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2018;13(3):228–38.

Ssewamala FM, Han CK, Neilands TB. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):191–8.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. Lakeway Drive, College Station: STATA press; 2008.

Blanton H, Jaccard J. Arbitrary metrics in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61(1):27.

Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(2):121–38.

Busza J, Strode A, Dauya E, Ferrand RA. Falling through the gaps: how should HIV programmes respond to families that persistently deny treatment to children? J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20789.

Gross R, Bandason T, Langhaug L, Mujuru H, Lowenthal E, Ferrand R. Factors associated with self-reported adherence among adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):322–6.

Kikuchi K, Poudel KC, Muganda J, Majyambere A, Otsuka K, Sato T, Mutabazi V, Nyonsenga SP, Muhayimpundu R, Jimba M, Yasuoka J. High risk of ART non-adherence and delay of ART initiation among HIV positive double orphans in Kigali, Rwanda. PLoS One. 2012;7(7).

Vreeman RC, Wiehe SE, Ayaya SO, Musick BS, Nyandiko WM. Association of antiretroviral and clinic adherence with orphan status among HIV-infected children in Western Kenya. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(2):163–70.

Holloway A, Watson HE. Role of self‐efficacy and behaviour change. Int J Nurs Pract. 2002;2:106–15.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff and the volunteer team at the International Center for Child Health and Development (ICHAD) in Uganda for monitoring the study implementation process. Our special thanks go to all children and their caregiving families who agreed to participate in the study.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Participation in the Suubi + Adherence study was voluntary. All caregivers provided written consent for their children to participate in the study. Similarly, all adolescents provided written assent to participate –obtained separately from their caregivers to avoid coercion. The study received Institutional Review Board approval from Columbia University (AAAK3852), from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (SS 2969), and from the Makerere University School of Public Health Higher Degrees Research Ethics Committee (210). The study is registered in the Clinical Trials database (NCT01790373).

Consort

The study adheres to the CONSORT guidelines.

Full study protocol

Funding

The Suubi + Adherence study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (Grant # 1R01HD074949–01, PI: Fred M. Ssewamala). NICHD had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of findings and preparing this manuscript. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PN and BC wrote the manuscript. CD managed the study data and DD led the data analysis process. FMS wrote the grant and obtained funding for the study. OSB and FMS reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and made significant additions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nabunya, P., Bahar, O.S., Chen, B. et al. The role of family factors in antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence self-efficacy among HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda. BMC Public Health 20, 340 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8361-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8361-1