Abstract

Background

In the northern region of China, many greenhouse vegetable farmers are exposed to high cumulative levels of pesticides due to long-term work in greenhouses that impacts their health. The aim of the current study was to identify the relationship between cumulative pesticide exposure and sleep disorders among farmers in Yinchuan, Northwest China.

Methods

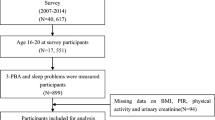

A cross-sectional study was conducted for 3 consecutive years in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Using a random sampling to select the resident teams, 1366 participants were enrolled, and information was collected via face-to-face interviews by trained investigators. Ordinal logistic, multinomial logistic and poisson logistic regression models were used to identify the associations between cumulative exposure intensity (CEI) and sleep disorders.

Results

High CEI (OR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.02–3.38) was associated with short sleep duration when compared with low CEI in the Full Model. CEI was not associated with long sleep duration. Self-rated sleep quality was associated with medium (OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.10–2.00) and high (OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.83–3.40) CEI. Similarly, having difficulty sleeping was associated with medium (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.02–2.24) and high (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.16–2.62) CEI. Differences in the associations by gender were also noted.

Conclusion

CEI was associated with sleep disorders, and gender differences were observed. Efforts should be made by local governments to address sleep problems that result from cumulative pesticide exposure in farmers, and gender differences should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sleep disturbances, a common risk factor of health conditions, affects millions of people around the world in modern society [1, 2]. Sleep disorders have also been found to be related to increased risks of all-cause morbidity and mortality [3], depression [4, 5], oral disease [6], and pain-related disease [7].

Pesticides are widely sold and used in agricultural production in China. The data according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) showed that the average use of pesticides per area of cropland (kg/ha) in each year in mainland China increased from 1990 to 2015. Pesticide exposure is a known risk factor of many diseases, such as cancer [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], asthma [15, 16], diabetes [17,18,19], Parkinson’s disease [20,21,22], leukemia [23, 24], mental diseases [25,26,27,28], and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [29] and may also be related to sleep disturbances. A case-control design study showed that increased tension, greater depression and fatigue, and more frequent symptoms of central nervous system disturbances were observed in pesticide-exposed women [30]. Although Baumert et al. revealed a positive correlation between pesticide exposure and sleep apnea among US male farmers [31], few studies have focused on the relationship between cumulative pesticide exposure (CEI) and sleep disorders.

Greenhouse planting is an important way to achieve higher crop production. More than 90% of the greenhouses in China are used for fresh vegetable or fruit production [32]; however, a previous study has reported that levels of pesticide residues in greenhouses was much higher than open-field vegetables due to the increased use of pesticides to control pests and improve crop yields [33]. Although another previous study reported that the exposure to pesticides in a greenhouse was lower than the acceptable daily intake, the threat of chronic cumulative exposure to pesticides is a health concern [34].

In the present study, 1366 independent farmers were enrolled in cross-sectional studies that were conducted in three consecutive year (2015, 2016 and 2017) to determine the prevalence of sleep disorders among greenhouse planting farmers and to evaluate the association with CEI.

Methods

Study setting

Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Northwest China, is located on the border of the Tengger Desert. This region lacks water resources (a very slight declining trend in rainfall occurred from 1960 to 2006), with the per capita water resource being only one-tenth of the national average [35]. Thus, more than 60,000 ha plastic greenhouses were established to satisfy the demand of fresh vegetables for local residents in 2013, most of which were financed by the government [36]. Detailed information on the study sites are displayed in Fig. 1.

Study design and data collection

Three cross-sectional studies were conducted from April to May in 2015, 2016, and 2017. As shown in Fig. 1, four villages (Liangtian, Maosheng, Yinhe, and Wudu) were chosen because of their long-term cooperation. In the investigation year for each village, one nonrepetitive resident team (primary resident unit in the village) was selected using a random sampling method. Six hundred questionnaires were distributed each year (150 questionnaires were sent to each resident team), and 448, 460, 458 valid, completed questionnaires were gathered in the 3 years; thus, the valid returned rate was 74.67, 76.67 and 76.33%, respectively.

The inclusion criteria for the participants were: adult greenhouse vegetable farmers who had lived at their current address at least 5 years and were engaged in vegetable planting in greenhouses more than 1 year.

Because most participants in our study were busy with farming work at the time of our investigations, verbal consent from the participating farmers was obtained prior to the interview, which helped to facilitate management and improve investigation compliance and efficiency. The design for this study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningxia Medical University (No.2014–090). If participant disagreed to investigate, then we recorded he/she as nonresponse case on the last back of questionnaire paper. The questionnaires (Additional file 1) were completed through a face-to-face interview by a trained interviewer, and the basic personal demographic/socioeconomic information and medical history were obtained.

Physical, psychological and social stress

The revised SRHMS (SRH measurement scale) was used to assess physical, psychological and social interaction stress for the target sample. The measurement tool was developed by Xu et al. [37, 38], and social, historical and cultural factors were considered. Forty-eight items were included in the scale, which also contained three subscales, and it has been shown to be suitable for the general population, with a high reliability, validity and sensitivity of the health status [37, 38]. The valid methods of statistical scores of each subscale were derived from previous studies [39].

Sleep status

Sleep disturbances were identified by the following seven questions: The question, “In the last month, how long do you sleep per night average?” was used to measure sleep duration, and the response was categorized into short [40] (sleeping time less or equal to 6 h), optimal (ranging from 6 to 9 h) and long sleep duration (more than or equal to 9 h). Self-rated sleep quality was evaluated by “What do you think your sleep quality was in the last month?”, and the corresponding options were “excellent” =1, “good” =2, “worse” =3, and “much worse” =4. Hypnotic drug use, difficulty falling asleep, sleep apnea, and nightmares, suffering from disturbance of falling asleep were evaluated by “How often have you used hypnotic drugs in the last month”; “How often have you had trouble falling asleep in the last month? (failure to fall asleep within 30 min)”; “How often have you had sleep apnea in the past 30 d?”; “How often have had dreaminess or nightmares in the last 30 d?”; “How often have you suffered from trouble falling asleep in the last 30 d?”. Options for these questions were: “None” =1, “less than once a week” =2, “1 to 2 times per week” =3, “more than or equal to 3 times per week” =4.

Cumulative pesticide exposure index

Although the information collected through the questionnaires ignored specific pesticide use and exposure levels in evaluating CEI, it would be synthesized from exposures to multiple potential pesticides.

There are several latent factors that may affect the level of exposure to pesticides, including the areas of planting, duration of work in sheds, mixing of spray pesticides, habits of spraying, equipment of protection, and habits of hygiene in personal work. CEI was evaluated using a quantitative method, with validity that had been proven by precious studies [41, 42]. CEI was calculated using an equation that, at best, provided a semi-quantitative index to represent actual pesticide exposure levels. Two algorithms were used, with several parameters in the formula, such as the habit of spraying, planting areas, and personal protective equipment (PPE), which came from the questionnaire. In the second formula, behavior in spray processes were considered as an additive predictor with mixing status and application method. This could occur because the awareness of personal protection is low among greenhouse farmers, as proven in our previous study [43], and many farmers had unhealthy habits, such as chatting, eating and drinking water during the spray process, and these habits may have increased their level of exposure to pesticides. The parameter description and assigned scores from the formula are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Finally, the CEI were placed into tertiles, lower-, medium-, and high CEI, due to the positive-skewed distribution (Additional file 2). Corresponding cut-pointing was 13.6 and 40.8.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaire-collected data were double-entered and checked using Epidata 3.01 software and then analyzed using SPSS 24.0. Frequencies and percentages were used to report categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables. The F test, Pearson, and Fisher χ2 test were conducted to estimate the differences in sociodemographic, life habit, and sleep situation variables among the different CEI groups. A poisson regression model, ordinal logistic regression model and multinomial logistic regression model (if the ordinal regression model test of parallel lines not passed then selected) were performed to assess the associations between CEI and sleep disorders; age was entered into the model as a continuous covariate.

Hypnotic drug use was recoded as a binary variable, “Yes” (constituted by < 1 times/week, 1–2 times/week, ≥3 times/week) and “No” (constituted by none) for the poisson regression model because there were only 26 participants that reported they used drugs. A multinomial logistic regression was used to identify the association between the sleep disorders and CEI, and optimal sleep duration was set as a reference. Two models were employed to test the associations between CEI and sleep disorders to identify whether the results were robust: Empty Model included CEI as an independent variable only, Full Model was adjusted by all potential confounders (include Number of family member, Gender, Ethnicity, Age, Education level, Marital status, Smoking status, Drinking status, Breakfast status, Family net income status, Number of chronic diseases, Survey year, Physical, psychological and social interaction stress). The proportional adds assumption for an ordinal logistic regression test was not passed for sleep apnea and nightmares, so the multinomial regression model was employed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A stratified analysis was performed by gender due to the gender differences in physiology and psychology.

Results

Demographic distribution

All farmers in the present study reported that they used at least one type of pesticide to control pests and to improve the production yield. The distribution of sleep disorders was observed according to the demographic/socioeconomic characteristics and spray behavior, and the results are shown in Additional file 3. At least one sleep disorder showed a significant distribution in one of the items that was used to calculate CEI, which indicates that pesticide spray habits and behavior might be associated with sleep disorders.

The distribution of the sociodemographic, life habit, and sleep information for the CEI groups is displayed in Table 3. Overall, 1366 independent farmers were included, with 448, 460, and 458 participants surveyed in 2015, 2016, and 2017, respectively. Males accounted for 53.1% of the participants, and more than 88% were of the Han ethnic. The mean age was 46.84 ± 10.27 (range 21–79) years. Significant differences in CEI levels occurred for ethnicity, educational level, breakfast habits, family net income level, and number of chronic diseases. Hui ethnicity, high educational status, highest family net income group, two or more chronic diseases, and irregular breakfast behavior had the higher risk of high CEI (P < 0.05).

Five sleep problems were found to be significant (P < 0.05) among the CEI groups from the univariate analysis (Table 3), excluding sleep apnea and nightmares. Sleep duration showed differences in distribution among the CEI groups, with 7.85, 7.74, and 7.51 average hours in the low, medium, and high CEI groups, respectively. The short, optimal and long sleep duration prevalence were 17.8, 59.4 and 22.8%, respectively. Significant differences in multi-comparisons favored high versus low CEI. Sleep duration in the high CEI group was less than in the other groups, and excellent self-rated sleep quality was observed in a smaller proportion (25.14%) of the high CEI group. Twenty-six participants reported that they had relied on medication to fall asleep in the past month; therein, 11 reported a drug use frequency of less than once a week, 7 reported 1 to 2 times per week, and 8 respondents indicated more than or equal to 3 times per week. A high frequency of medication use occurred in the high CEI group. The distribution of characteristics related to drug use are shown in Additional file 4, and three variables had significant differences. A higher proportion of having trouble falling asleep was observed in the medium and high CEI groups, and the frequency was from one to three times per week.

Odds ratio for sleep items

Empty Model in Table 4 show that high CEI was significantly associated with short sleep duration compared with low CEI. Nonsignificant associations were observed for comparisons with the medium CEI group. There was not enough evidence to identify the relationship between CEI and long sleep duration. For self-rated sleep quality, high CEI had a tighter relationship than medium (2.46- vs. 1.37-fold likelihood, P-value< 0.05). A similar trend occurred in trouble falling asleep (1.82- and 1.64-fold significant likelihood, respectively). Nonsignificant differences were observed for drug use, sleep apnea, nightmares and suffered from sleep disorders in all models (data not shown for the last three items).

The results showed robust conditions in Full Model, where the low CEI was used as the reference. Short sleep duration had a 1.56-fold significant odds relationship with high CEI. Nonsignificant associations were observed for medium CEI with short sleep duration and all CEI groups with long sleep duration. An association also found between CEI and self-rated sleep quality and having trouble falling asleep, with nearly 1.5-fold likelihood in medium CEI and 2.50- and 1.74-fold likelihood for self-rated sleep quality and trouble falling asleep in high CEI.

The sensitivity analysis was based on the sample of excluded individuals who reported using hypnotic drugs to help themselves fall asleep. The results are represented in Additional file 5, which indicates similar associations as those shown in Table 4. Stable results were carried out and further validated it.

Stratified analysis

Stratification was according to gender, and the results are displayed in Additional file 6. For sleep duration (contained long and short sleep duration simultaneously), nonsignificant relationships with CEI were shown in the subsample of males and females. Similar results occurred for hypnotic drug use in each stratum, as there were nonsignificant associations with CEI. Both medium and high CEI were associated with self-rated sleep quality in the female, but the significant correlation was only observed with high CEI in males, for which the estimated odds ratio was close to the overall sample. In the female, having trouble falling asleep was associated with high CEI. In males, this finding only occurred in medium CEI.

Discussion

This study revealed that adverse associations between CEI and sleep problems among greenhouse vegetable farmers. Due to the natural environmental and socioeconomical limitations in Northwest China, the local government authorities encouraged farmers to engage in jobs related to the production of greenhouse vegetables to satisfy the huge demands of the local residents for fresh vegetables. Farmers working in greenhouses would have increased CEI due to the warm, humid climate and long-term, frequent pesticide use [44], and consequently, high pesticide exposure is a risk to farmers in greenhouses that should be a public health concern.

Short sleep duration was significantly associated with high CEI, and nonsignificant results occurred for long sleep duration. One plausible reason is that most pesticides have detrimental impacts on human health, which occur via the influence of neurologic functions, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibition [45,46,47], and it could easily make related nerves active. Short sleep duration reflects nervous stress or disruption or highly reactive nerve cells, and exposure to pesticides might delay sleep time and reduce sleep duration. Quality of sleep [48] is an integrated index indicating the quality of sleep situations. Self-rated sleep quality was measured in the current study, and significant associations occurred with CEI at both the medium and high levels. High CEI showed a bigger likelihood to perceive worse sleep quality than medium. These findings are in line with the results of Zhao et al. [49], who reported that long-term exposure to pesticides could cause a sleep-awaking function disorder, which could lead to poor quality of sleep. Furthermore, it has also been validated by animal experiments [50] under restricted and controlled conditions.

Although exposure to carbofuran was associated with sleep apnea in 1569 U.S. male farmers in a previous report [31], a nonsignificant relationship between pesticide exposure and sleep apnea was observed in the present study. Possible reasons for this difference may be the different measurement tools used to determine sleep apnea in the two studies. The lack of a uniform concept for understanding nightmares and dreaminess might explain their nonsignificant association with CEI, as well as suffering from sleep. Furthermore, the high pain tolerance of farmers may have reduced the reflection probability of sleep disorders in local farmers. Having trouble falling asleep had significant associations with both medium and high CEI. A large portion of people that had trouble falling asleep had insomnia that due to physical pain and the use of medications. Oral exposure was a common pathway [46] in the farming spray pesticide process that tended to impact the respiratory system, meanwhile the corresponding symptoms, such as apnea and chest tightness, also occurred [51], which might influence individuals’ perception of sleep quality as well. Physical pain from respiratory diseases could also contribute to the negative relationship with sleep. Hypnotic drug use, sleep apnea and nightmare suffering from sleep disorders did not have significant relationships with CEI. The possible reason for this may be that these issues are more serious. Since the 2000s, the Chinese government has banned the sale of highly toxic pesticides and has undergone efforts to regulate the use of pesticides. That may explain the nonsignificant finding.

Differences occurred by gender for the relationship between sleep disorders and CEI. Sensitivity-perceived sleep quality was observed in the female sample and was significantly associated with both medium and high CEI level, meanwhile statistically significant differences in the male sample only occurred at the high level. This means that the quality of sleep for females was susceptible to pesticides exposure, possibly because women are more exquisite and pay attention to detail, so depending on the psychological condition, it would easily lead to a larger reduction in the quality of sleep for women than man. Interestingly, feeling trouble to sleep was associated with the medium and high levels for males and females, respectively, which was a novel finding of this research and may need further study.

Some limitations of this study need to be noted. The lack of information on specific pesticide exposures could limit the applicability of these findings. CEI may be underestimated because not all pesticide exposure came from greenhouse planting processes, as other emission sources, such as regular household exposure [52] and open environment exposure, were not considered in the current study. Memory recall bias could exist due to pesticide use and personal information recall, which might affect the precision of the results. Sleep problems were measured at one time-point; therefore, this measurement would not reflect sleep status changes and might lead to results that do not reflect the real sleep situation. Compared with a cohort study design, the fact that the current cross-sectional design could not achieve causal inference is the major limitation. Future studies should include a cohort study design and the follow-up evaluations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, despite the above limitations, the results showed the stable effects of CEI associated with sleep problems. CEI was positively associated with short sleep duration and negatively associated with self-perceived sleep quality, and trouble falling asleep in plastic greenhouse vegetable farmers. High CEI showed a stronger correlation coefficient than medium CEI groups compared with the low exposure. Gender differences in the relationship between CEI and self-rated sleep quality and having trouble falling asleep were observed. Efforts should be made to address sleep problems due to the effects of cumulative pesticide exposure in farmers, taking into account gender differences.

Abbreviations

- CEI:

-

Cumulative Exposure Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- IRR:

-

Incidence-rate ratios

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

References

Research IOMU, Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;47(4):473–4.

Chuang HC, Su TY, Chuang KJ, Hsiao TC, Lin HL, Hsu YT, Pan CH, Lee KY, Ho SC, Lai CH. Pulmonary exposure to metal fume particulate matter cause sleep disturbances in shipyard welders. Environ Pollut. 2017;232:523–32.

Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. SLEEP. 2010;33(5):585–92.

Nutt D, Wilson S, Paterson L. Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):329–36.

Brunello N, Armitage R, Feinberg I, Holsboertrachsler E, Léger D, Linkowski P, Mendelson WB, Racagni G, Saletu B, Sharpley AL. Depression and sleep disorders: clinical relevance, economic burden and pharmacological treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42(3):107–19.

Huynh N, Emami E, Helman J, Chervin R. Interactions between sleep disorders and oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2014;20(3):236–45.

Roizenblatt M, Neto NSR, Tufik S, Roizenblatt S. Pain-related diseases and sleep disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2012;45(9):792–8.

Koutros S, Lynch CX, Lee W, Hoppin J, Christensen C, Andreotti G, Freeman L, Rusiecki J, Hou L, Sandler D. Heterocyclic aromatic amine pesticide use and human cancer risk: results from the U.S. agricultural health study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(5):1206–12.

Loffredo CA. Pesticides, gene polymorphisms, and bladder Cancer among Egyptian agricultural workers. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2015;70(1):19–26.

Samanic CM, Roos AJD, Stewart PA, Rajaraman P, Waters MA, Inskip PD. Occupational exposure to pesticides and risk of adult brain tumors. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(8):976–85.

Teras LR, Diver WR, Turner MC, Krewski D, Sahar L, Ward E, Gapstur SM. Residential radon exposure and risk of incident hematologic malignancies in the Cancer prevention study-II nutrition cohort. Environ Res. 2016;148:46–54.

Clara V, Andrés V, Noelia M, Andrea R, Elena R, Mariel NE, Claudia C. Chlorpyrifos inhibits cell proliferation through ERK1/2 phosphorylation in breast cancer cell lines. Chemosphere. 2015;120:343–50.

Merhi M, Raynal H, Cahuzac E, Vinson F, Cravedi JP, Gamet-Payrastre L. Occupational exposure to pesticides and risk of hematopoietic cancers: meta-analysis of case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(10):1209–26.

Lerro C, Koutros S, Andreotti G, Hines C, Lubin J, Zhang Y, Beane FL. 0301 Use of acetochlor and cancer incidence in the agricultural health study cohort. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(5):1167–75.

Ndlovu V, Dalvie MA, Jeebhay MF. Asthma associated with pesticide exposure among women in rural Western cape of South Africa. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57(12):1331–43.

Hernández AF, Parrón T, Alarcón R. Pesticides and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(2):90–6.

Tang M, Chen K, Yang F, Liu W. Exposure to organochlorine pollutants and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):1–12.

Azandjeme CS, Bouchard M, Fayomi B, Djrolo F, Houinato D, Delisle H. Growing burden of diabetes in sub-saharan Africa: contribution of pesticides ? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2013;9(6):437–49.

Everett CJ, Frithsen IL, Diaz VA, Koopman RJ, Simpson WM Jr, Mainous AG 3rd. Association of a polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, a polychlorinated biphenyl, and DDT with diabetes in the 1999-2002 National Health and nutrition examination survey. Environ Res. 2007;103(3):413–8.

Moisan F, Spinosi J, Delabre L, Gourlet V, Mazurie JL, Bénatru I, Goldberg M, Weisskopf MG, Imbernon E, Tzourio C. Association of Parkinson’s disease and its subtypes with agricultural pesticide exposures in men: a case–control study in France. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(11):1123–9.

Pezzoli G, Cereda E. Exposure to pesticides or solvents and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80(22):2035–41.

Brouwer M, Koeman T, Pa VDB, Kromhout H, Schouten LJ, Peters S, Huss A, Vermeulen R. Occupational exposures and Parkinson's disease mortality in a prospective Dutch cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(6):448–55.

Maele-Fabry GV, Lantin AC, Hoet P, Lison D. Residential exposure to pesticides and childhood leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2011;37(1):280–91.

Maryam Z, Sajad A, Maral N, Zahra L, Sima P, Zeinab A, Zahra M, Fariba E, Sezaneh H, Davood M. Relationship between exposure to pesticides and occurrence of acute leukemia in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(1):239–44.

Lee DH, Lind PM, Jr JD, Salihovic S, Van BB, Lind L. Association between background exposure to organochlorine pesticides and the risk of cognitive impairment: a prospective study that accounts for weight change. Environ Int. 2016;89-90:179–84.

Cherry N, Burstyn I, Beach J, Senthilselvan A. Mental health in Alberta grain farmers using pesticides over many years. Occup Med. 2012;62(6):400–6.

Beard JD, Hoppin JA, Richards M, Alavanja MCR, Blair A, Sandler DP, Kamel F. Pesticide exposure and self-reported incident depression among wives in the agricultural health study. Environ Res. 2013;126(4):31–42.

Kim J, Shin DH, Lee WJ. Suicidal ideation and occupational pesticide exposure among male farmers. Environ Res. 2014;128(2):52–6.

Hu L, Luo D, Zhou T, Tao Y, Feng J, Mei S. The association between non-Hodgkin lymphoma and organophosphate pesticides exposure: a meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2017;231(Pt 1):319–28.

Bazylewicz-Walczak B, Majczakowa W, Szymczak M. Behavioral effects of occupational exposure to organophosphorous pesticides in female greenhouse planting workers. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(5):819–26.

Baumert BO, Carnes MU, Hoppin JA, Jackson CL, Sandler DP, Freeman LB, Henneberger PK, Umbach DM, Shrestha S, Long S, et al. Sleep apnea and pesticide exposure in a study of US farmers. Sleep Health. 2017;4(1):20–26.

Chang J, Wu X, Liu A, Wang Y, Xu B, Yang W, Meyerson LA, Gu B, Peng C, Ge Y. Assessment of net ecosystem services of plastic greenhouse vegetable cultivation in China. Ecol Econ. 2011;70(4):740–8.

Cai QY, Mo CH, Wu QT, Katsoyiannis A, Zeng QY. The status of soil contamination by semivolatile organic chemicals (SVOCs) in China: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2008;389(2):209–24.

Eissa FI. Determining pesticide residues in honey and their potential risk to consumers. Pol J Environ Stud. 2014;23(5):1573–80.

Li Y, Wu Y, Conway D, Preston F, Lin E, Zhang J, Wang T, Jia Y, Gao Q, Shifeng Z. Climate and livelihoods in rural Ningxia: final report. The impacts of climate change on Chinese agriculture - phase II National Level Study final report. Didcot: AEA Group; 2008.

Wu B. The factor analysis about the current state of the Yinchuan suburban vegetable greenhouses pesticide residues and plant personnel cardiovascular health impact. Yinchuan: Ningxia Medical University; 2016.

Jun X, Rong G, Yongsheng L, Ping W, Weiyi H, Zhiliang C. The study of responsiveness on Sel-rated health measurement scale (the revised version 1.0). Chin J Health Stat. 2003;20(05):272–5.

Xu Y, Xue Z. A comparative study of SCL-90 and self-rated health Measurenment scale in college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2003;3:232.

Xu J, Zhang J, Feng L, Qiu J. Self-rated health of population in southern China: association with socio-demographic characteristics measured with multiple-item self-rated health measurement scale. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):393.

Kerkhof GA. Epidemiology of sleep and sleep disorders in the Netherlands. Sleep Med. 2017;30:229–39.

Dosemeci M, Alavanja MC, Rowland AS, Mage D, Zahm SH, Rothman N, Lubin JH, Hoppin JA, Sandler DP, Blair A. A quantitative approach for estimating exposure to pesticides in the agricultural health study. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002;46(2):245–60.

Kang ML, Park SY, Lee K, Oh SS, Sang BK. Pesticide metabolite and oxidative stress in male farmers exposed to pesticide. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2017;29(1):5.

Bing W, Huifang Y, Lingqin Z, Jian S, Ji Z, Lijun D. The using status and the influencing factors in greenhouse Workers in Yinchuan. J Ningxia Med Univ. 2016;38(6):670–3.

Ohlberger J, Staaks G, Hölker F. Effects of temperature, swimming speed and body mass on standard and active metabolic rate in vendace ( Coregonus albula ). J Comp Physiol B Biochemical Systemic & Environmental Physiology. 2007;177(8):905–16.

Linz DH, MD MS, MD RRS, Lockey JE, MD MS, MD PJK, RS PD, CHR PD, Pflaumer JE, MSN RN, RTM PD, GKL PD, MD REA. Health status of pesticide applicators with attention to the peripheral nervous system. J Agromedicine. 1994;1(1):23–42.

Kim KH, Kabir E, Jahan SA. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci Total Environ. 2016;575:525–35.

Meyerbaron M, Knapp G, Schäper M, Van TC. Meta-analysis on occupational exposure to pesticides--neurobehavioral impact and dose-response relationships. Environ Res. 2015;136:234–45.

Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S10–7.

Zhao Y, Zhang M, Huan YU, Xing-Nuan LI, Wei HE, Zhou YC. Survey of correlation between Long-term exposure to organophosphorus pesticides and sleep quality of peasants. Occupation & Health. 2010;26(18):2051–3.

Nadzhimutdinov KN, Kamilov IK, Muzrabekov SM. Influence of pesticides on the duration of hexobarbital-induced sleep. Farmakologiya I Toksikologiya. 1974;37(5):533–7.

Ye M, Beach J, Martin JW, Senthilselvan A. Pesticide exposures and respiratory health in general populations. J Environ Sci-China. 2017;51(1):361–70.

Sheng C, Gu S, Yue W, Yao Y, Wang G, Yue J, Wu Y. Exposure to pyrethroid pesticides and the risk of childhood brain tumors in East China. Environ Pollut. 2016;218:1128–34.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research team for their contribution to the survey data collection. Additionally, we thank the participants for their agreement to take part in the present study and the four villages’ management for organizing the local residents.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from the Project for Developing Top Western Disciplines in University (Public Health and Preventive Medicine) (No. NXYLXK2017B08), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81460490) and the Important Research Topic of Health and Family Planning Commission of Ningxia (No. 2017-NW-018). The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript and the decision to publish.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article. Additional data are available on individual request at jpingl1273@163.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JPL was the main author of the manuscript and was involved in all aspects of this paper. YXH and DNT participated in the data collection and cleaning. SLH and XS performed the data analysis, explained the results, and modified the manuscript. HFY conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningxia Medical University (No.2014–090), and oral consent was obtained from participants prior to the interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire. (DOCX 33 kb)

Additional file 2:

The distribution and describe of CEI. (DOCX 25 kb)

Additional file 3:

Sleep disorders distribution in behavior variables of pesticides used characteristic and significant test (n, %). (DOCX 56 kb)

Additional file 4:

Distribution of characteristic in participants between hypnotic use and nonuse. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 5:

Association between sleep issues and CEI levels from different adjusted models among plastic greenhouses vegetable farmers exclude sample of hypnotic drug use. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 6:

Subset adjusted odds ratio of sleep issues with CEI levels (reference: low CEI level) among plastic greenhouse vegetable farmers, Yinchuan, China. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Hao, Y., Tian, D. et al. Relationship between cumulative exposure to pesticides and sleep disorders among greenhouse vegetable farmers. BMC Public Health 19, 373 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6712-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6712-6