Abstract

Background

Given the importance of knowing the potential impediments and enablers for physical activity (PA) and sedentary behaviour (SB) in a specific population, the aim of this study was to systematically review and summarise evidence on individual, social, environmental, and policy correlates of PA and SB in the Thai population.

Methods

A systematic review of articles written in Thai and English was conducted. Studies that reported at least one correlate for PA and/or SB in a healthy Thai population were selected independently by two authors. Data on 21 variables were extracted. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Results

A total of 25,007 records were screened and 167 studies were included. The studies reported associations with PA for a total of 261 variables, mostly for adults and older adults. For most of the variables, evidence was available from a limited number of studies. Consistent evidence was found for individual-level and social correlates of PA in children/adolescents and adults and for individual-level correlates of PA in older adults. Self-efficacy and perceived barriers were consistently associated with PA in all age groups. Other consistently identified individual-level correlates in adults and older adults included self-rated general health, mental health, perceived benefits, and attitudes towards PA. Consistent evidence was also found for social correlates of PA in adults, including social support, interpersonal influences, parent/family influences, and information support. The influence of friendship/companionship was identified as a correlate of PA only in children/adolescents.

A limited number of studies examined SB correlates, especially in older adults. The studies reported associations with SB for a total of 41 variables. Consistent evidence of association with SB was only found for obesity in adults. Some evidence suggests that male adults engage more in SB than females.

Conclusions

More Thai studies are needed on (i) PA correlates, particularly among children/adolescents, and that focus on environment- and policy-related factors and (ii) SB correlates, particularly among older adults. Researchers are also encouraged to conduct longitudinal studies to provide evidence on prospective and causal relationships, and subject to feasibility, use device-based measures of PA and SB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Even though physical activity (PA) has been identified as the ‘best buy’ in public health [1] and national actions for the promotion of PA have been employed in many countries [2], population levels of PA are still declining [2,3,4]. In contrast, time spent performing sedentary behaviour (SB) is increasing [3, 4]. SB refers to any waking activity in a sitting, reclining, or lying position with low energy expenditure [5]. In the academic literature, SB has been conceptualised in two ways: (i) as a health risk factor ‘independent’ of PA [6]; and (ii) as a part of the time-use composition consisting of sleep, SB, and PA co-dependent time-use components [7]. In both conceptualisations, SB is deemed a potentially important factor for population health. Nevertheless, there seem to be barriers to the promotion of PA and reduction of SB, especially in low- and middle-income countries. These barriers include workforce shortages in the PA/SB sector (e.g. lack of PA promoters), weak networks of collaboration with other sectors (e.g. education, sports, and transportation), the lack of effective actions, and lack of knowledge about what approaches to PA promotion and SB reduction are feasible [2, 8]. These have been major challenges in Thailand, where efforts have been made to design and implement policy-level interventions.

To develop effective programs or interventions to increase PA and reduce SB, there is a need to understand correlates of these behaviours in specific populations. Public health experts advise that this need is urgent in low- and middle-income countries [2, 9]. Moreover, given substantial differences between geographical areas in social, cultural, environmental, and economic factors, it is important to explore PA and SB correlates in specific countries so that feasible interventions can be developed and designed based on local data [10]. Studies on PA correlates in low- and middle-income countries have recently started receiving more attention [2, 9,10,11,12,13]. Since 1987, and especially over the last two decades, PA has been the focus of a plethora of Thai epidemiological research, and the attention has most commonly been placed on its correlates [14].

In Thailand, the data from a 2015 population-representative survey on PA and SB showed that 21-25% of Thai children and adolescents (aged 6–17 years) achieved the recommended level of PA (i.e. 60 minutes a day) [15]. In addition, more than 78% of Thai children and adolescents engaged in two or more hours of SB [15]. Around 40% of Thai adults (aged 18 and above) met the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations for moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) [16, 17]. Interestingly, 33.8% of Thai adults reported a high level of SB and no MVPA in the past week [16]. A better understanding of what makes some Thai population groups less active than others may help tackle the problem of insufficient PA.

Like other healthy behaviours, PA and SB are influenced by many factors [9, 18,19,20,21,22]. However, the focus to date has mostly been on individual-level correlates, such as sex, age, attitude, and self-rated general health [9, 11, 14, 20,21,22]. The social-ecological approach has been widely adopted to understand the interrelationships among multiple factors that contribute to PA and SB, including individual, social, environmental, and policy factors [9, 18,19,20,21,22]. The full spectrum of PA/SB correlates has been analysed in several reviews, mostly in high-income countries such as the United States, Australia, and Canada [9, 20,21,22,23,24,25]. Studies from low- and middle-income countries including Thailand have rarely been included [9, 20,21,22,23,24,25].

Given the importance of knowing which variables are associated with PA and SB in a specific population, the aim of this study was to systematically review and summarise the available evidence on individual, social, environmental, and policy correlates of PA and SB in Thai children, adolescents, adults, and older adults. We also aimed to identify the key gaps in the literature on PA and SB correlates in Thailand and provide recommendations for future research.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted by following the PRISMA guidelines [26]. The primary literature search was conducted from database inception to September 2016 using the following ten bibliographic databases: Academic Search Premier; CINAHL; Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition; MasterFILE Premier; PsycINFO; PubMed/MEDLINE; Scopus; SPORTDiscus; Web of Science; and the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD). The secondary literature search was conducted by using three main sources, including: the Google and Google Scholar internet search engines (using search terms in both Thai and English); references of the studies that were selected in the primary search; and the websites/databases of Thai health-related organizations and institutes including the Division of Physical Activity, Ministry of Public Health; Thai Health Promotion Foundation; Health System Research Institute; Physical Activity Research Institute; Thai National Research Repository; Thai Thesis Database; Thai NCD Network; Kasetsart University Research; Chulalongkorn University Intellectual Repository; and Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

Two researchers (NL and KS) independently screened all references obtained from the search results, removed duplicates, and selected studies. The third author (ZP) resolved discrepancies about the study selections. The eligibility criteria included the following: Published peer-reviewed journal papers, theses, reports, and conference papers written in Thai or English were included, and reviews, commentaries, and editorials were excluded. Observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, and prospective) that targeted healthy Thai people (as opposed to patients with a specific disease or health condition) of any ages were considered eligible for inclusion. To be included, the studies had to present the association of at least one variable with total PA (e.g. minutes per day or METs per week), MVPA, moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA), meeting/not meeting PA guidelines (e.g. meeting the PA recommendation of 60 minutes of MVPA per day), domain-specific PA (e.g. recreation, transportation), and exercise participation. For SB measures, total SB or sitting time or frequency and/or duration in one or more of sedentary activities including television (TV) viewing, screen time, and computer/internet use were included. Both self-reported and devise-based measurements qualified for inclusion. Longitudinal studies that analysed PA or SB as predictors of an outcome variable, were not considered eligible for inclusion.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the selected studies: (a) general bibliographical information, such as publication type and language; (b) research methods used, including sampling techniques; (c) characteristics of the study population such as sex, age, and region; (d) description of PA/SB measure, including the PA type as a dependent variable and validity information; (e) specific correlate(s) with an assigned, categorized domain such as socio-demographic, psychological, and social factors; and (f) the type of statistical analysis used in the included studies. Data were extracted separately for three age groups: children and adolescents (<18 years old); adults (between 18 and 59 years old); and older adults (>60 years old). The full extraction tables are provided in the Additional file 1.

Data coding and pooling

To pool the results of individual studies, we used the procedure proposed by Sallis et al. [24]. The pooled associations between potential correlates and PA and SB were classified as: a) mostly positive associations (denoted by ‘+’); b) mostly negative associations (denoted by ‘-‘); or c) mostly non-significant, indeterminate, or inconsistent associations (denoted by ‘?’). The codes were determined based on the percentage of significantly positive, significantly negative, and non-significant associations, according to the rules presented in Table 1 [24]. The classification system was slightly adapted from the original categorisation used by Sallis et al. [24], to better reflect the implication of non-significant relationships. The results from the most adjusted analysis reported in a paper were used for the classification. Letters ‘M’ and ‘F’ were used to indicate findings for male and female participants when results were reported separately for sexes.

A synthesis of the findings of this review was structured by applying the social-ecological model of PA/SB, where all correlates were categorised into key components of the model including individual (e.g. socio-demographic, biological), social (e.g. interpersonal, cultural), physical environment (e.g. facilities, neighbourhood), and policy (e.g. education and workplace policies) factors. The pooled results are presented separately for children and adolescents (6-17 years), adults (18-59 years), and older adults (60 years and over). We used this threshold for the ‘older adults’ group, because, according to the Thai Labour Protection Act, the retirement age applies to adults aged 60 years and more [27].

Risk of bias

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [28]. NOS was designed to evaluate the quality of observational studies for several purposes, such as to include/exclude studies for meta-analysis, weight studies, and address areas that need methodological improvements [29]. The three aspects of studies that were assessed using the NOS tool included the selection of study groups (4 items, maximum 5 points), adjustments for potential confounders (1 item, maximum 2 points), and ascertainment of exposure and outcomes (2 items, maximum 3 points) [28, 29]. The overall score was calculated as the sum of points across the three categories. The overall scores were classified into three groups: low (<5 points), moderate (5-7 points), and high (>7 points) study quality [30].

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

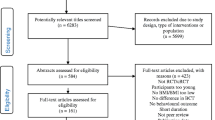

The search and study selection processes are illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 25,007 records were identified. Of these, 167 papers met the eligibility criteria and were included in the present review. Most studies focused on PA only (76%; n = 127), 15 studies (9%) examined SB correlates only, and 25 studies (15%) examined correlates of both PA and SB. The included articles were published between 1993 and 2016. All studies used a cross-sectional design. The average sample size cited in the studies was 3,317 and ranged from 27 to 87,134. Two studies included only male participants (1.2%), 17 studies included only female participants (10.2%), and the remainder included both sexes (88.6%; n = 148). Half of the studies were conducted among adults (50.3%; n = 100), followed by older adults (28.6%; n = 57) and children/adolescents (21.1%; n = 42). Of these, twenty-nine studied on adults/older adults and three on adolescents/adults. Most of the included publications were articles published in peer-reviewed journals (69.5%; n = 116), more than a quarter were doctoral and master’s theses (26.9%; n = 45), and the remaining publications were reports (2.4%; n = 4) and conference papers (1.2%; n = 2).

Nearly all studies were conducted using self-report instruments to measure PA (97.6%; n = 163). Three studies used accelerometers (1.8%) and one study used pedometers (0.6%). Sixty-three percent of the studies used previously validated PA measures (n = 96). More than half of the studies measured exercise participation (54.9%; n = 89), followed by MVPA (19.1%; n = 31) and total PA (13.6%; n = 22). Domain-specific PA was assessed in 6.8% of the studies (n = 11), which mainly included recreation and household PA. The remaining studies assessed VPA (3.1%; n = 5) and MPA (2.5%; n = 4). Presenting correlates of each PA type separately are available in the Additional file 2: Tables S1-S22.

SB was assessed using self-report instruments in all but one study. Most instruments used to measure SB had been previously validated (62.5%; n = 25). Watching television was the main SB independently investigated in several studies (30.6%; n = 15), followed by total SB time (20.4%; n = 10). Other individual sedentary activities included computer and internet use that were examined in 16.3% (n = 8) and 10.2% (n = 5) of the studies respectively. Screen time, which refers to TV viewing and computer use combined, was assessed in 12.2% of the studies (n = 6). The remainder observed the total duration of sitting during leisure time (6.1%; n = 3) and at work (4.1%; n = 2).

Methodological quality

The median overall score of the included studies on the NOS was 6 (‘moderate quality’). Twenty-three studies were categorised as ‘high quality’, 34 were considered ‘low quality’, while the remainder were of moderate quality (n = 110). Among the high-quality studies, seven studies dealt with children and adolescents, seven focused only on adults, two only on older adults, and seven on both adults and older adults. It was, therefore, not considered appropriate to perform a sensitivity analysis using only findings from high-quality studies, due to the fact that too few of these studies were available. The results of the quality assessment for all the included studies can be found in the Additional file 3.

Physical activity correlates

The included studies reported associations with PA for a total of 261 variables [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181]. Almost half of the variables were significantly associated with PA (47.5%; n = 124). Multiple factors were assessed, including individual, social, physical, and policy environment variables. The most frequently studied factors were those at the individual level (81.6%; n = 213). The statistically significant correlates most often included psychological factors, followed by biological, demographic, and health behavioural and lifestyle factors (Fig. 2).

Correlates of children’s and adolescents’ physical activity

A total of 52 potential PA correlates were studied in Thai children and adolescents (Table 2). Consistent evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following individual-level factors: younger age, being a male, higher self-efficacy, and lower perceived barriers. Consistent evidence of association with higher PA was found for the social factor of greater friendship/companionship influences. No consistent evidence was found for environmental and policy correlates of PA.

Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following individual-level factors: lower household income, going to mixed-gender schools (compared with single-gender schools), higher self-rated general health, greater enjoyment of PA/exercise, more past PA/exercise experience, higher resilience, higher perceived physical competence, greater knowledge of PA/exercise, not having asthma and hypertension, lower body dissatisfaction, lower duration of TV viewing, and lower grade point average. Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following social factors: greater parent/family influences, more involvement with friends, ease in making friends, better social supports, greater teacher influences, greater general interpersonal influences, and better information support. Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following environmental factors: better environmental supports, and better neighbourhood environment. No evidence was found for policy correlates of PA.

The associations between PA and school grade and body mass index (BMI) were mostly non-significant or largely inconsistent.

Correlates of adults’ physical activity

In total, 120 potential correlates of PA were studied in Thai adults (Table 3). Consistent evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following individual-level factors: higher self-rated general health, better mental health, positive attitudes towards PA/exercise, higher self-efficacy, higher perceived benefits of PA/exercise, lower perceived barriers for PA/exercise, and more spare time. Consistent evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following social factors: better social support, greater general interpersonal influences, greater parent/family influences, and better information support. No consistent evidence was found for environmental and policy correlates of PA.

Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following individual-level factors: being underweight, higher HDL-cholesterol level, higher VO2Max, lower triglycerides (TG) level, lower total cholesterol: HDL-C ratio, lower risk of having high TG, lower resting heart rate, lower haematocrit level, lower age-related macular degeneration, more years of working experience, having a ‘dream job’, ever attended a workshop on exercise, higher dietary calcium intake, higher sunlight exposure, having osteoporosis, greater overall health belief, higher career satisfaction, higher intrinsic motivation, healthier dietary habits, past PA/exercise experience, more enjoyment of PA/exercise, higher outcome expectancies, greater intention to take part in PA/exercise, better physical and functional fitness, engaging in enjoyable sports, lower extrinsic motivation, and lower stress level. Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following social factors: better cultural support, family members’ involvement in PA/exercise, and greater friendship/companionship influences. Some evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following environmental factors: less exposure to urban environment, later months of a calendar year (compared with the other months), and shorter distance to shopping place. Some evidence supported association between higher PA and the policy factor of better supportive education policies.

The associations between PA and age, sex, marital status, education level, university year, faculty, household income, occupation, campus/working location, BMI, being overweight, obesity, history of sickness, and knowledge of PA/exercise were mostly non-significant or largely inconsistent.

Correlates of older adults’ physical activity

A total of 89 potential correlates of PA were studied in Thai older adults (Table 4). Consistent evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following individual-level factors: higher self-rated general health, better mental health, positive attitudes towards PA/exercise, higher self-efficacy, higher perceived benefits of PA/exercise, lower perceived barriers for PA/exercise, higher outcome expectancies, greater knowledge of PA/exercise, and better physical and functional fitness. No consistent evidence was found for social, environmental, and policy correlates of PA.

Some evidence of association with higher PA was found for the following individual-level factors: being a senior-citizen club member, being a Buddhist (when compared with being a Muslim), not being obese, lower triglyceride (TG), lower total cholesterol: HDL-C ratio, less likely to have high TG, lower resting heart rate, higher bone mineral density (BMD), higher HDL-cholesterol, higher VO2max, better health-related quality of life, ever attended a workshop on exercise, higher dietary calcium intake, higher sunlight exposure, better saliva flow rate, less daily duty, lower hematocrit level, less likely to have abnormal symptoms, not having osteoporosis, not having age-related macular degeneration, not having periodontal disease, not perceiving exercise-related effect, lower score on Timed Up and Go test, lower sedentary time, greater perceived control, higher subjective norms, higher life satisfaction, higher career satisfaction, commitment to a plan of exercise, ability to do daily activities, greater enjoyment of PA/exercise, more spare time, better oral-health behaviours, and greater intention to PA/exercise. Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following social factors: greater friendship/companionship influences, better hospital staff support, and better information support. Some evidence supported associations between higher PA and the following environmental factors: better physical environment, better supportive neighbourhood environment, a sense of community, less exposure to urban environment, living in a residential community, and shorter distance to shopping place. No evidence was found for policy correlates of PA.

The associations between PA and age, sex, marital status, education level, and household income were mostly non-significant or largely inconsistent.

Sedentary behaviour correlates

The included studies reported associations with SB for a total of 41 variables [32, 42, 45, 46, 56, 67, 79, 80, 83, 89, 93, 97, 102, 109, 116, 117, 119, 120, 122, 124, 126, 143, 155, 161, 162, 182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196]. More than half of them were significantly associated with SB (53.7%; n = 22). In older adults, the included studies investigated only potential SB correlates at the individual level, while they also examined social factors in children and adolescents, and in adults, also environmental factors.

Correlates of children’ and adolescents’ sedentary behaviour

A total of 19 potential correlates of SB were studied in Thai children and adolescents (Table 5). Some evidence of association with higher SB was found for older age/higher school grade, higher body weight, higher BMI, more physical pain, less participation in sports, more time spent with family, and more participation in extracurricular activities. Non-significant associations with SB were consistently found for sex, being overweight, and obesity.

Correlates of adults’ sedentary behaviour

In total, 17 potential correlates of SB were studied in Thai adults (Table 6). A consistent association with SB was found for obesity. Some evidence of association with higher SB was found for being a male, higher education level, low back pain, higher alcohol consumption, lower grade point average, more musculoskeletal symptoms, heavy Internet use, less transport PA, less recreation PA, and more exposure to an urban environment.

Correlates of older adults’ sedentary behaviour

Only five potential correlates of SB were studied in Thai older adults (Table 7). No consistent evidence from multiple studies was found on SB correlates in this age group. Some evidence of an association with higher SB was found for obesity, higher alcohol consumption, worse mental health, less active transport, and less recreational PA.

Discussion

Physical activity correlates

A range of factors potentially associated with PA levels in the Thai population were identified at the individual, social, environmental, and policy levels. However, consistent evidence of association with PA was found only for individual-level and social correlates in children/adolescents and adults and for individual-level correlates in older adults. The summary findings suggest that PA promotion strategies in Thailand need to address several intrapersonal and interpersonal factors and may need to be tailored specifically for different age groups. The lack of consistent evidence from multiple studies for environmental and policy correlates may partially be explained by the fact that most of the included studies assessed individual-level and social correlates only. Future research should, therefore, place more focus on examining potential environmental and policy correlates of PA in the Thai population. Our findings also suggest that correlates of PA in Thailand may be different than in some other countries, calling for more focused, individual-country reviews of this kind.

In the current review, we found consistent evidence for the associations of younger age and male sex with higher PA only in children and adolescents. Among Thai adults and older adults these associations were inconsistent. A previous review for low- and middle-income countries [2] reported “mixed or weak” associations of gender and age with PA, whilst reviews for high-income countries [9, 23, 25] reported consistent associations. This might suggest that socioeconomic context in a given country may play a role in shaping the relationships of age and gender with PA. This should be further explored in future reviews of PA correlates in low- and middle-income countries and individual studies on gender- and age-specific determinants of PA. Given a relatively large number of studies included in the current review examining the association of PA with age and sex, the lack of consistent evidence in adults and older adults may suggest that the situation in Thailand is indeed different than in some other countries. For most other demographic variables, evidence on their association with PA was scarce or inconsistent in all age groups. More research is needed to understand which demographic characteristics are associated with higher PA levels in Thailand.

Evidence has strongly supported associations between different aspects of health and PA regardless of age [1, 197,198,199,200]. Whilst we found evidence on the association of PA with self-reported general health in all age groups and with mental health in adults and older adults, evidence for most other, specific health variables and biological factors was scarce or inconsistent. Moreover, it should be noted that some of the identified health-related variables associated with PA may be outcomes of PA rather than factors affecting PA [201]. For example, it may be that in Thai adults high PA improves general health status, whilst it may also be that healthier Thai adults are more likely to engage in PA. The causality might as well be bidirectional [201]. From the cross-sectional studies included in this review, it was not possible to conclude about the causal direction of the relationships. Clearly, more research is needed on biological and health-related correlates of PA in the Thai population. Furthermore, a large proportion of non-significant associations found between obesity and PA in Thai adults is in accordance with findings of most previous, non-country-specific reviews [6]. Although it may seem reasonable to assume that obese people are less likely to engage in PA, and that more physically active people are less likely to get obese, this association is clearly not so straightforward. Multiple other factors, particularly diet, need to be considered to understand the potential association between PA and obesity.

Previous reviews have identified physical skills, abilities, and fitness as important correlates of PA in all age groups [25, 202, 203]. Based on our review, it seems that this is also the case in the Thai context. It should be noted, however, that findings for nearly every variable in this category are based on results from only one study. Furthermore, findings for behavioural and lifestyle correlates of PA were mixed. We found evidence suggesting that higher PA is associated with past PA/exercise experience in children/adolescents and adults and knowledge of PA/exercise in children and older adults. Providing exercise instructions and opportunities to gain experience in PA/exercise might, therefore, be an effective way to increase PA participation in the Thai population. We also found that having more spare time may be associated with higher PA in adults and older adults. Time management interventions aimed at achieving balanced time use, to ensure enough spare time is available for engaging in PA, may be needed to increase PA levels in the Thai population [7].

It is interesting that consistent evidence of association with PA across all three age groups was found only for two psychological factors; namely self-efficacy and perceived barriers. Our finding regarding self-efficacy is in accordance with previous studies that identified this characteristic as an important determinant of PA behaviour across lifespan; from childhood to older age [2, 9, 25, 204, 205]. Furthermore, perceived barriers for PA are one’s evaluations of potential obstacles to start engaging in PA and/or to maintain regular PA (e.g. time constraints, lack of skills, unsuitable weather conditions). Although barriers for PA/exercise may be perceived differently by members of different age groups [206], they seem to be consistently negatively associated with PA behaviour for people of all ages in the Thai population. In previous, multinational reviews, including studies conducted in low-, middle-, and high-income countries, the authors reached inconsistent conclusions with respect to barriers to PA/exercise [2, 9, 24, 25]. For example, whilst Sallis et al. [24] suggested that perceived barriers are significantly associated with PA in children, van der Horst et al. suggested they are not [207]. Similarly, inconclusive findings for adults and older adults have also been reported by other authors [2, 25]. It may be that the association between perceived barriers to PA and PA levels is country-specific. Thus, acquiring country-level evidence may be needed to design effective interventions to tackle perceived barriers to PA.

Social support (e.g. from parents, family, and friends) was identified as a motivator for increased participation in PA, especially for Thai children/adolescents and adults. This is in accordance with findings of previous reviews [2, 9, 24, 208,209,210]. Interestingly, friend or peer influences have been shown to have a significant direct effect on PA among adolescents, while parents seem to have a more indirect influence [211]. In the current review, we found evidence suggesting that influences from both friends and parents may play important roles in children’s/adolescents’ engagement in PA. Several studies included in the present review also suggested that parental or family influences may be important correlates of PA in Thai adults. Although only one study showed a positive correlation between friendship/companionship influences and PA in this age group, the evidence should not be ignored, as this was a relatively large study [74]. Social support from friends and companions seem to be an enabler of PA also in Thai older adults. In this age group, support from hospital staff to engage in PA may be important. Therefore, improving different aspects of social support need to be taken into consideration when designing PA strategies and interventions for the Thai population.

Worldwide, a range of environmental attributes have been associated with PA, such as community resources, neighbourhood safety, transportation environment, access to sport and exercise facilities, routine destinations in daily life, and accessibility of public green spaces [2, 9, 18, 24, 25, 208,209,210, 212,213,214,215,216]. Interestingly, access and proximity to facilities appear to be important contributors to youth PA regardless of country’s economic status [2, 9, 24, 208, 209, 216]. Evidence on the associations between most aspects of physical environment and PA in Thai adults is inconclusive. This is mainly because of the limited number of studies conducted on this topic. Some evidence suggests that PA of children/adolescents and older adults in Thailand may be associated with neighbourhood design, which is consistent with findings from other, non-country specific reviews [217, 218]. Given the plethora of evidence from other countries and some evidence from Thailand, it seems important to improve features of the physical environment to increase PA participation in the Thai population. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to investigate environmental correlates of PA that are specific for Thailand.

In terms of policy-related correlates of PA, very few variables have been investigated. Only five studies have examined the effects of policies on PA in Thailand, and were carried out at the local level (i.e. the school and workplace) and among adults [70, 75, 84, 87, 219]. Some evidence suggests that education policies (in specific, university policies) may be associated with PA, whilst a single study did not find a significant association between workplace policies and PA. Further investigations on the potential impact of policies on PA is encouraged.

Sedentary behaviour correlates

A limited number of studies have examined correlates of SB in Thai populations, especially in older adults. Some evidence suggests that, among Thai adults, males engage more in SB than females. This is in accordance with the associations between overall SB and sex found in several other countries [20]. Furthermore, consistent evidence from multiple studies was found for the association between obesity and SB in Thai adults. An umbrella review has suggested that available evidence is not supportive of this association in adults [220]. It might, therefore, be that the findings of the current review reflect only a context-specific situation in Thailand. Based on the available evidence, it seems that interventions for reducing SB should particularly focus on obese individuals, as being obese seems to be associated with more SB. It should be noted, however, that all Thai studies supporting this association are cross-sectional; hence, no inferences can be made about the direction of the relationship. Nevertheless, a previous longitudinal study suggested that obesity may lead to a subsequent increase in SB, whilst there was no evidence for the association in the other direction [221]. Besides, we found mostly non-significant associations between being overweight and engaging in SB. It might, therefore, be that only more severe issues with excessive weight lead to increases in SB. We also found some evidence supporting the association between SB and musculoskeletal disorders. Experiencing bodily pain was associated with higher SB in children and adolescents, whilst having musculoskeletal symptoms and low back pain were associated with higher SB in adults. These findings must be taken with caution, because previous longitudinal studies provided very little evidence in support of such associations [6, 222]. Furthermore, alcohol consumption was found to be associated with increased SB in both adults and older adults. These are, however, findings from one study only (examining both age groups), and given the inconsistent evidence for this association found in a previous review [20], this warrants further investigation. Associations of other variables and SB were either non-significant or supported by a single study, which demonstrates the need for more studies on SB in Thai populations, and particularly in older adults.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has several strengths. Most previous reviews of PA/SB correlates did not present country-specific findings. In the current review, for the first time, findings on potential PA/SB correlates in the Thai population were extracted and summarised from many original studies (n = 167). Previous reviews on PA/SB correlates have cited primarily research published in the English language, which may have introduced bias into their findings. In this review, we included publications in both Thai and English; the languages that Thai researchers predominantly use in academic communication. Furthermore, we examined numerous potential correlates, particularly for PA, at all levels—individual, social, environmental, and policy. This comprehensive approach enabled us to better elucidate the complexity of PA and SB behaviours in the Thai population.

This review was not without limitations. Firstly, we did not use a formal meta-analytical procedure to combine the results of individual studies. Given the large number of analysed correlates and great heterogeneity between studies in terms of measures of PA/SB and statistical methods they used, we opted for the procedure for summarising results of individual studies proposed by Sallis et al. [24]. This procedure has been used in several previous systematic reviews in the field of public health. Secondly, relying on evidence from cross-sectional studies has prevented us from drawing conclusions about the direction of the summarised relationships. This was inevitable, because we did not identify any longitudinal studies on factors affecting PA/SB in Thailand. Finally, the findings of this review may have been influenced by recall errors, because the clear majority of included studies relied on self-reported PA/SB, and only a few used devices to assess these behaviours.

Recommendations for future research

A limited number of studies examined SB correlates, particularly for older adults. More research is needed to understand why Thais engage in excessive SB and which factors to address to prevent it. Furthermore, less than one-fourth of all studies on PA correlates were conducted among children and adolescents. These age groups should, therefore, be designated as a priority target for future research on PA correlates. For most correlates of both PA and SB, only few findings from individual studies are available. This is particularly the case for social, environmental, and policy-related variables. More research is needed on most potential correlates of PA and SB in the Thai population. Another challenge stems from the fact that all studies included in this review used cross-sectional designs. To provide evidence on prospective and causal relationships between the variables and PA/SB, longitudinal and intervention studies should be conducted. In addition, to improve the validity of PA/SB estimates and avoid the potential recall bias, subject to feasibility, researchers are encouraged to employ devices, such as accelerometers, pedometers, or multi-sensor measures.

Conclusions

This review is one of the first to summarise within-country correlates of PA and SB across population groups. Given a range of differences between the findings of the current review and the findings of previous non-country specific reviews, it may be important to consider correlates of PA and SB at the country-level. This may be particularly relevant when such reviews are completed to inform national- and local-level public health interventions.

Findings of the current review suggest that several factors are associated with PA levels in the Thai population. Based on the available evidence, to increase PA in Thailand, public health interventions should focus on helping individuals: improve self-efficacy; circumvent perceived barriers for PA; improve general and mental health; find enough spare time to engage in PA; improve physical skills, abilities, and fitness; gain knowledge about and experience in exercise; and receive adequate social support for participation in PA. Furthermore, the body of literature on correlates of SB in Thailand is limited. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that interventions for reducing SB in Thai adults should primarily target obese individuals, as they seem to be at a greater risk of high SB.

More Thai studies are needed on PA correlates, particularly among children and adolescent and with a focus on environment- and policy-related factors. Much greater commitment is needed to investigating correlates of SB in Thailand, particularly among older adults. The Thai Government and public health stakeholders should provide a systematic support to such research, as it provides knowledge that is crucial for designing public health policies, strategies, and interventions.

Abbreviations

- MPA:

-

Moderate Physical Activity

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

- NDLTD:

-

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations

- PA:

-

Physical Activity

- SB:

-

Sedentary Behaviour

- TV:

-

Television

- VPA:

-

Vigorous Physical Activity

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Morris JN. Exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease: today’s best buy in public health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(7):807–14.

Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, Heath GW, Inoue S, Kelly P, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1325–36.

Ng SW, Popkin BM. Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev. 2012;13(8):659–80.

Katzmarzyk PT, Mason C. The physical activity transition. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(3):269–80.

Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):75.

de Rezende LF, Rodrigues Lopes M, Rey-López JP, Matsudo VK, Luiz OC. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105620. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105620.

Pedišić Ž, Dumuid D, Olds T. Integrating sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity research in the emerging field of time-use epidemiology: definitions, concepts, statistical methods, theoretical framework, and future directions. Kinesiology. 2017;49(2):252–69.

Topothai T, Chandrasiri O, Liangruenrom N, Tangcharoensathien V. Renewing commitments to physical activity targets in Thailand. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1258–60.

Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJF, Martin BW, Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380:258–71.

Atkinson K, Lowe S, Moore S. Human development, occupational structure and physical inactivity among 47 low and middle income countries. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;3:40–5.

Koyanagi A, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D. Correlates of low physical activity across 46 low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional analysis of community-based data. Prev Med. 2018;106:107–13.

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Firth J, Hallgren M, Schuch F, Lahti J, et al. Physical activity correlates among 24,230 people with depression across 46 low- and middle-income countries. Prev Med. 2017;221:81–8.

Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Hallgren M, Schuch F, Veronese N, et al. Physical activity correlates among people with psychosis: Data from 47 low- and middle-income countries. Prev Med. 2018;193:412–7.

Liangruenrom N, Suttikasem K, Craike M, Bennie JA, Biddle SJH, Pedisic Z. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour research in Thailand: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):733.

Amornsriwatanakul A, Nakornkhet K, Katewongsa P, Choosakul C, Kaewmanee T, Konharn K, et al. Results from Thailand’s 2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(11 Suppl 2):S291–S8.

Liangruenrom N, Topothai T, Topothai C, Suriyawongpaisan W, Limwattananon S, Limwattananon C, et al. Do Thai people meet recommended physical activity level?: the 2015 national health and welfare survey. J Health Syst Res Inst. 2017;11(2):205–20 (Thai paper).

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(12):1793–812.

Stokols D. Translating socio-ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10(4):282–98.

O’Donoghue G, Perchoux C, Mensah K, Lakerveld J, van der Ploeg H, Bernaards C, et al. A systematic review of correlates of sedentary behaviour in adults aged 18–65 years: a socio-ecological approach. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):163.

Uijtdewilligen L, Nauta J, Singh AS, van Mechelen W, JWR T, van der Horst K, et al. Determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in young people: a review and quality synthesis of prospective studies. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(11):896–905.

Chastin SFM, Buck C, Freiberger E, Murphy M, Brug J, Cardon G, et al. Systematic literature review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in older adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):127.

Sallis JF, Owen N. Physical Activity and Behavioral Medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. p. 110–134.

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–75.

Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Loannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Detsiri U. Deemed Retirement Age Now 60-Right to Statutory Severance. 2017. http://www.pricesanond.com/knowledge/employment-and-labour/blogdeemed-retirement-age-now-60-right-to-statutory-severance-php.php. Accessed 16 April 2018.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 28 April 2018.

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(27):iii–x 1-173.

Gao Y, Huang YB, Liu XO, Chen C, Dai HJ, Song FJ, et al. Tea consumption, alcohol drinking and physical activity associations with breast cancer risk among Chinese females: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7543–50.

Akkayagorn L, Tangwongchai S, Worakul P. Cognitive profiles, hormonal replacement therapy and related factors in Thai menopausal women. Asian Biomedicine. 2009;3(4):439–44.

Amini M, Alavi-Naini A, Doustmohammadian A, Karajibani M, Khalilian A, Nouri-Saeedloo S, et al. Childhood obesity and physical activity patterns in an urban primary school in Thailand. Rawal Med J. 2009;34(2):203–6.

Amnatsatsue K. Measurement of physical function in Thai older adults [dissertation]. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2002.

Angkurawaranon C, Lerssrimonkol C, Jakkaew N, Philalai T, Doyle P, Nitsch D. Living in an urban environment and non-communicable disease risk in Thailand: Does timing matter? Health Place. 2015;33:37–47.

A-piwong C. Exercise behaviors of students at university of the Thai Chamber of Commerce [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Graduate School, Srinakharinwirot University; 2011.

Aree-Ue S, Petlamul M. Osteoporosis Knowledge, Health Beliefs, and Preventive Behavior: A Comparison between Younger and Older Women Living in a Rural Area. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(12):1051–66.

Ar-Yuwat S, Clark MJ, Hunter A, James KS. Determinants of physical activity in primary school students using the health belief model. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:119–26.

Asawachaisuwikrom W. Physical activity and its predictors among older Thai adults. J Sci Technol Humanit. 2003;1(1):65–76.

Asawachaisuwikrom W. Factors influencing physical activity among older adults in Saensuk sub-district, Chonburi Province. Chonburi, Thailand: Burapha University; 2004 Oct. Report No.:ISBN974-382-100-7.

Assantachai P, Maranetra N. Nationwide Survey of the Health Status and Quality of Life of Elderly Thais Attending Clubs for the Elderly. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(10):938–46.

Assantachai P, Sriussadaporn S, Thamlikitkul V, Sitthichai K. Body composition: Gender-specific risk factor of reduced quantitative ultrasound measures in older people. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(8):1174–81.

Atchara P, Kasem N, Mayuree T, Suporntip P, Seabra A, Carvalho J. Associations between Physical Activity, Functional Fitness, and Mental Health among Older Adults in Nakornpathom, Thailand. Asian J Exerc Sports Sci. 2014;11(2):25–35.

Aungsusuknarumol C. Exercise for health behavior of community college students in Northern colleges of physical education [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand, Thailand: Graduate School, Srinakharinwirot University; 2000.

Baiya N, Tiansawad S, Jintrawet U, Sittiwangkul R, Pressler SJ. A Correlational Study of Physical Activity Comparing Thai Children With and Without Congenital Heart Disease. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2014;18(1):29–41.

Banks E, Lim L, Seubsman SA, Bain C, Sleigh A. Relationship of obesity to physical activity, domestic activities, and sedentary behaviours: Cross-sectional findings from a national cohort of over 70,000 Thai adults. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):762.

Banwell C, Lim L, Seubsman SA, Bain C, Dixon J, Sleigh A. Body mass index and health-related behaviours in a national cohort of 87,134 Thai open university students. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(5):366–72.

Binhosen V, Panuthai S, Srisuphun W, Chang E, Sucamvang K, Cioffi J. Physical activity and health related quality of life among the urban Thai elderly. Thai J Nurs Res. 2003;7(4):231–43.

Boonrin P, Choeychom S, Nantsupawat W. Predictive factors on exercise behaviors of nursing students. J Nurs Health Care. 2015;33(2):176–86.

Charoensook K. Factors affecting exercise behaviors of teachers in Nakhonpanom province in academic year 2007 [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Graduate School, Srinakharinwirot University; 2007.

Charoneying W, Asawachaisuwikrom W, Junprasert S. Factors affecting exercise behavior of upper secondary level school students in schools upper the office of Prachinburi educational service area. J Fac Nurs Burapha Univ. 2006;11(1):23–34.

Chawla N, Panza A. Assessment of childhood obesity and overweight in Thai children grade 5-9 in BMA bilingual schools, Bangkok. Thai J Health Res. 2012;26(6):317–22.

Chinuntuya P. A causal model of exercise behavior of the elderly in Bangkok metropolis [dissertation]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University; 2001.

Chongwatpol P, Gates GE. Differences in body dissatisfaction, weight-management practices and food choices of high-school students in the Bangkok metropolitan region by gender and school type. Public Health Nutrition. 2016;19(7):1222–32.

Chotikacharoensuk P. Physical activity and psychological well-being among the elderly [master’s thesis]. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Graduate School, Chiang Mai University; 2002.

Chuamoor K, Kaewmanee K, Tanmahasamut P. Dysmenorrhea among Siriraj nurses; Prevalence, quality of life, and knowledge of management. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(8):983–91.

Churangsarit S, Chongsuvivatwong V. Spatial and social factors associated with transportation and recreational physical activity among adults in Hat Yai city, Songkhla, Thailand. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(6):758–65.

Dajpratham P, Chadchavalpanichaya N. Knowledge and practice of physical exercise among the inhabitants of Bangkok. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(11):2470–6.

Dancy C, Lohsoonthorn V, Williams MA. Risk of dyslipidemia in relation to level of physical activity among Thai professional and office workers. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39(5):932–41.

Dasa P. Exercise behaviors and perceived barriers to exercise among female faculty members in Chiang Mai University [master’s thesis]. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Graduate School, Chiang Mai University; 2001.

Decharat S, Phethuayluk P, Maneelok S. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms among Dental Health Workers, Southern Thailand. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2016; http:dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5494821.

Deenan A, Thanee S, Sumonwong W. A Comparative Study of Exercise Behaviors, Eating Behaviors, Serum Lipids, and Body Mass Index of Thai Adolescents: Urban and Rural Areas of the Eastern Seaboard of Thailand. Chonburi, Thailand: Burapha University; 2001. Report No.:ISBN974-352-001-5.

Ekpanyaskul C, Sithisarankul P, Wattanasirichaigoon S. Overweight/obesity and related factors among Thai medical students. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 2013;25(2):170–80.

Ethisan P, Somrongthong R, Ahmed J, Kumar R, Chapman RS. Factors Related to Physical Activity Among the Elderly Population in Rural Thailand. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;8(2):71–6.

Henry CJ, Webster-Gandy J, Varakamin C. A comparison of physical activity levels in two contrasting elderly populations in Thailand. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13(3):310–5.

Howteerakul N, Suwannapong N, Sittilerd R, Rawdaree P. Health risk behaviours, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among rural community people in Thailand. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 2006;18(1):3–9.

Ing-Arahm R, Suppuang A, Imjaijitt W. The study of medical students' attitudes toward exercise for health promotion in Phramongkutklao College of Medicine. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(Suppl 6):S173–8.

Insawang T, Selmi C, Cha'on U, Pethlert S, Yongvanit P, Areejitranusorn P, et al. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) intake is associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a rural Thai population. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-50.

Intorn S. Relationships between selected factors and exercise behaviors of middle aged adult in Nakorn Sawan province [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University; 2003.

Ishimaru T, Arphorn S. Hematocrit levels as cardiovascular risk among taxi drivers in Bangkok, Thailand. Ind Health. 2016;54:433–8.

Jarupanich T. Prevalence and risk factors associated with osteoporosis in women attending menopause clinic at Hat Yai Regional Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(5):865–9.

Jermsuravong W, Vongjaturapat N, Li F. The influence of exercise motivation on exercise behavior among Thai youth. J Popul Soc Stud. 2008;17(1):93–114.

Jirapinyo P, Wongarn R, Limsathayourat N, Maneenoy S, Somsa-Ad K, Thinpanom N, et al. Adolescent Height : Relationship to Exercise, Milk Intake and Parents' Height. J Med Assoc Thai. 1997;80(10):641–6.

Jitnarin N, Kosulwat V, Boonpraderm A, Haddock CK, Poston WS. The relationship between smoking, BMI, physical activity, and dietary intake among Thai adults in central Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(7):1109–16.

Jitramontree N. Predicting exercise behavior among Thai elders: Testing the theory of planned behaviour [dissertation]. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 2003.

Julvanichpong T. Predictive Factors of Exercise Behaviors of Junior High School Students in Chonburi Province. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering. 2015;9(7):2633-8.

Junlapeeya P. Model testing of exercise behavior in Thai female registered nurses in an urban hospital [dissertation]. College Park, MD: University of Maryland; 2005.

Kabkaew T. Factors affecting exercise behavior of assistant-nurse students, Hospital for Tropical Disease, Mahidol University [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand, Thailand: Graduate School, Kasetsart University; 2006.

Kaewthummanukul T, Chanprasit C, Poosawang R, Tripibool D, Songkham W. Predictors of exercise among practical nurses. Nurs J. 2008;35(1):22–35.

Kanchanomai S, Janwantanakul P, Pensri P, Jiamjarasrangsi W. Prevalence of and factors associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in the spine attributed to computer use in undergraduate students. Work. 2012;43(4):497–506.

Kantachuvessiri A, Sirivichayakul C, Kaewkungwal J, Tungtrongchitr R, Lotrakul M. Factors associated with obesity among workers in a metropolitan waterworks authority. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(4):1057–65.

Keawvilai S. The predictive factors on exercise behaviors of undergraduate students Rajamangala University of Technology Phra Nakhon. Bangkok, Thailand: Rajamangala University of Technology Phra Nakhon; 2009.

Khotcharrat R, Patikulsila D, Hanutsaha P, Khiaocham U, Ratanapakorn T, Sutheerawatananonda M, et al. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration among the elderly population in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(8):790–7.

Khruakhorn S, Sritipsukh P, Siripakar Y, Vachalathit R. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among the university staff. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(Suppl 7):S142–S8.

Khwanchuea R, Thanapop S, Samuhasaneeto S, Chartwaingam S, Mukem S. Bone Mass, Body Mass Index, and Lifestyle Factors: A Case Study of Walailak University Staff. Walailak J Sci Tech. 2012;9(3):263–75.

Kitrungpipat N, Phannithit A. Self-health care behavior student in Silpakorn University Phrtchaburi IT Campus. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Management Science, Silpakorn University; 2012.

Kittipimpanon K. Factors Associated with Physical Performance among Elderly in Urban Poor Community [master’s thesis]. Nakorn Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University; 2006.

Klainin-Yobas P, He HG, Lau Y. Physical fitness, health behaviour and health among nursing students: A descriptive correlational study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(12):1199–205.

Kongcheewasakul C, Klanarong S, Sathirapanya C. Exercise behavior for health of Rajamangala Srivijaya university students, Songkhla Campus. AL-NUR. 2014;9(16):59–70.

Konharn K, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC. Socioeconomic status and objectively measured physical activity in Thai adolescents. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(4):712–20.

Konharn K, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC. Differences between weekday and weekend levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in Thai adolescents. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP2157–NP66.

Kraithaworn P, Sirapo-ngam Y, Piaseu N, Nityasuddhi D, Gretebeck KA. Factors predicting physical activity among older Thais living in low socioeconomic urban communities. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2011;15(1):39–56.

Kruavit A, Chailurkit LO, Thakkinstian A, Sriphrapradang C, Rajatanavin R. Prevalence of Vitamin D insufficiency and low bone mineral density in elderly Thai nursing home residents. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12(1):49.

Lim LL-Y, Kjellstrom T, Sleigh A, Khamman S, Seubsman SA, Dixon J, et al. Associations between urbanisation and components of the health-risk transition in Thailand. A descriptive study of 87,000 Thai adults. Glob Health Action. 2009;2(1):1914.

Laosupap K, Sota C, Laopaiboon M. Factors affecting physical activity of rural Thai midlife women. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(8):1269–75.

Le D, Garcia A, Lohsoonthorn V, Williams MA. Prevalence and risk factors of hypercholesterolemia among Thai men and women receiving health examinations. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37(5):1005–14.

Leethong-in M. A causal model of physical activity in healthy older Thai people [dissertation]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University; 2009.

Limpawattana P, Assantachai P, Krairit O, Kengkijkosol T, Wittayakom W, Pimporm J, et al. The predictors of skeletal muscle mass among young Thai adults: A study in the rural area of Thailand. Biomed Res (India). 2016;27(1):29–33.

Mahanonda N, Bhuripanyo K, Leowattana W, Kangkagate C, Chotinaiwattarakul C, Panyarachun S, et al. Regular exercise and cardiovascular risk factors. J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83(Suppl 2):S153–S8.

Mongkhonsiri P. The mindful self: sense of self and health-promoting lifestyle behaviours among Thai college women [dissertation]. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Massey University; 2007.

Morinaka T, Limtrakul PN, Makonkawkeyoon L, Sone Y. Comparison of variations between percentage of body fat, body mass index and daily physical activity among young Japanese and Thai female students. J Physiol Anthropol. 2012;31(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1880-6805-31-21.

Mosuwan L, Geater AF. Risk factors for childhood obesity in a transitional society in Thailand. Int J Obesity. 1996;20(8):697–703.

Mo-suwan L, Nontarak J, Aekplakorn W, Satheannoppakao W. Computer Game Use and Television Viewing Increased Risk for Overweight among Low Activity Girls: Fourth Thai National Health Examination Survey 2008-2009. Int J Pediatr. 2014; https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/364702.

Nakhern P, Kananub P. Exercise behavior of public health officer in Nakhorn Pathom province. Nonthaburi, Thailand: Division of Epidemiology, Ministry of Public Health; 2000 Jan. 6 p. Report No.:ISSN0125-7447.

Nanakorn S, Osaka R, Chusilp K, Tsuda A, Maskasame S, Ratanasiri A. Gender differences in Health-Related practices among University students in Northeast Thailand. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 1999;11(1):10–5.

Napradit P, Pantaewan P, Nimit-arnun N, Souvannakitti D, Rangsin R. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Royal Thai Army personnel. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(2):335–40.

Narin J, Taravut T, Sangkoumnerd T, Thimachai P, Pakkaratho P, Kuhirunyaratn P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with sufficient physical activity among medical students in Khon Kaen University. Srinagarind Med J. 2008;23(4):389–95.

Ng N, Hakimi M, Minh HV, Juvekar S, Razzaque A, Ashraf A, et al. Prevalence of physical inactivity in nine rural INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems in five Asian countries. Global Health Action. 2009;2:44–53.

Ngamjaroen A. Factors affecting exercise behavior among health group members at Ratchaburi province [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Graduate School, Silpakorn University; 2005.

Nintachan P. Resilience and risk-taking behavior among Thai adolescents living in Bangkok, Thailand [dissertation]. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University; 2007.

Osaka R, Nanakorn S, Sanseeha L, Nagahiro C, Kodama N. Healthy dietary habits, body mass index, and predictors among nursing students, northeast Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30(1):115–21.

Othaganont P, Sinthuorakan C, Jensupakarn P. Daily living practice of the life-satisfied Thai elderly. J Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(1):24–9.

Page RM, Suwanteerangkul J. Self-rated health, psychosocial functioning, and health-related behavior among Thai adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(1):120–5.

Page RM, Taylor J, Suwanteerangkul J, Novilla LM. The influence of friendships and friendship-making ability in physical activity participation in Chiang Mai, Thailand high school students. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2005;8:95–103.

Pancharean S, Wanjan P. Influencing factors of exercise behavior among high school students. Thai J Nurs Counc. 2007;22(3):80–90.

Pasiri P, Kuhirunyaratn P. Knowledge, attitude and practice related to physical exercise among health volunteers in Amphoe Meuang, Nong Bua Lam Phu province. Paper presented at: The 34th National Graduate Research Conference; 2015 March 27; Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Pawloski LR, Kitsantas P, Ruchiwit M. Determinants of overweight and obesity in Thai adolescent girls. Int J Med. 2010;3(2):352–6.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Leisure time physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour and lifestyle correlates among students aged 13–15 in the association of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) member states, 2007–2013. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:217.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Apa P, Somchai V. Obesity and Lifestyle Factors in Male Hospital Out-patients in Thailand. Gender Behav. 2015;13(2):6668–74.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Apidechkul T. Heavy Internet use and its associations with health risk and health-promoting behaviours among Thai university students. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;26(2):187–94.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Overweight and obesity and associated factors among school-aged adolescents in Thailand. African J Phys Health Educ Recreation Dance. 2013;19(2):448–58.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Bullying and its associated factors among school-aged adolescents in Thailand. Sci World J. 2013;2013:254083.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence of overweight and underweight and its associated factors among male and female university students in Thailand. HOMO-J Comparative Human Biol. 2015;66(2):176–86.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Kassean HK, Tsala JPT, Sychareun V, Müller-Riemenschneider F. Physical inactivity and associated factors among university students in 23 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(5):539–49.

Pensri P, Janwantanakul P, Chaikumarn M. Biopsychosocial Factors and Musculoskeletal Symptoms of the Lower Extremities of Saleswomen in Department Stores in Thailand. J Occup Health. 2010;52(2):132–41.

Piaseu N, Komindr S, Chailurkit LO, Ongphiphadhanakul B, Chansirikarn S, Rajatanavin R. Differences in bone mineral density and lifestyle factors of postmenopausal women living in Bangkok and other provinces. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(6):772–81.

Pipatkasira K. The comparison of physical activity in urban and rural Thai school children using validated Thai physical activity questionnaire [master’s thesis]. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University; 2008.

Podang J, Sritara P, Narksawat K. Prevalence and factors associated with metabolic syndrome among a group of Thai working population: a cross sectional study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(Suppl 5):S33–41.

Polin S. Relationships between personal factors, self-efficacy in exercise, perceived benefits of exercise, college environment and exercise behaviors of nursing students [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University; 1999.

Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen T, Kosulwat V, Rojroongwasinkul N, Charoenkiatkul S, Eisman J, et al. Effects of physical activity and dietary calcium intake on bone mineral density and osteoporosis risk in a rural Thai population. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(10):807–13.

Poolsawat W. Physical activity of the older adults in Bangkok [master’s thesis]. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University; 2007.

Poomsrikaew O. Social-cognitive factors and exercise behavior among Thais [dissertation]. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago; 2011.

Pothiban L. Risk factor prevalence, risk status, and perceived risk for coronary heart disease among Thai elderly [dissertation]. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama at Birmingham; 1993.

Prapimporn Chattranukulchai S, Pariya P, Orawan P, La-or C, Tanarat L, Suwannee C, et al. Vitamin D status is a determinant of skeletal muscle mass in obesity according to body fat percentage. Nutrition. 2015;31(6):801–6.

Prombumroong J, Janwantanakul P, Pensri P. Prevalence of and biopsychosocial factors associated with low back pain in commercial airline pilots. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2011;82(9):879–84.

Rapheeporn K, Sasithorn T, Suchittra S, Suree C, Sirirak M. Waist Circumference: A Key Determinant of Bone Mass in University Students. Walailak Jo Sci Technol. 2013;10(6):665–76.

Razzaque A, Nahar L, Minh HV, Ng N, Juvekar S, Ashraf A, et al. Social factors and overweight: evidence from nine Asian INDEPTH Network sites. Global Health Action. 2009;2:54–9.

Rungruang S, Pattanittum P, Kamsa-ard S. Physical Exercise of Khon Kaen University Students. J Health Sci. 2006;15(2):315–22.

Saithong T, Boonyasopun U, Naka K. Relationships among situational influences, interpersonal influences, commitment to exercise and exercise behavior of exercise group members in Phang-nga province. Thai J Nurs Counc. 2004;19(2):39–52.

Samnieng P, Ueno M, Zaitsu T, Shinada K, Wright FA, Kawaguchi Y. The relationship between seven health practices and oral health status in community-dwelling elderly Thai. Gerodontology. 2013;30(4):254–61.

Sangthong R, Wichaidit W, McNeil E, Chongsuvivatwong V, Chariyalertsak S, Kessomboon P, et al. Health behaviors among short- and long- term ex-smokers: Results from the Thai National Health Examination Survey IV, 2009. Prev Med. 2012;55(1):56–60.

Siangsai C, Sukonthasab S. Factors related physical activities of higher education institutes students in Bangkok metropolis. J Sports Sci Health. 2015;16(3):63–75.

Siramaneerat I, Sawangdee Y. Socioeconomic-demographic factors and health-risk behaviors in the Thai population. Population. 2015;29(6):457–63.

Siriphakhamongkhon S, Sawangdee Y, Pattaravanich U, Mongkolchati A, Hlaing ZN, Rattanapan C, et al. Determinants and consequences of childhood overweight-health status and the child s school achievement in Thailand. J Health Res. 2016;30(3):165–71.

Siripul P. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Thai adolescents [dissertation]. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University; 2000.

Srichaisawat P. Factors affecting exercise behaviors of undergraduate students, Srinakharinwirot University. J Faculty Phys Educ. 2006;9(2):5–18.

Sritara C, Thakkinstian A, Ongphiphadhanakul B, Pornsuriyasak P, Warodomwichit D, Akrawichien T, et al. Work- and travel-related physical activity and alcohol consumption: Relationship with bone mineral density and calcaneal quantitative ultrasonometry. J Clin Densitometry. 2015;18(1):37–43.

Stewart O, Yamarat K, Neeser KJ, Lertmaharit S, Holroyd E. Buddhist religious practices and blood pressure among elderly in rural Uttaradit Province, northern Thailand. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(1):119–25.

Sukrasorn S. Decision making process and determinants of exercise among urban elderly in Prachuapkhirikhan province. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate School, Mahidol University; 2008.

Sumkaew J. Physical exercise behaviors for health of nursing students in Bangkok Metropolis [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University; 2002.

Sumpowthong K. Physical activity assessment and determinants of active living: the development of a model for promoting physical activity among older Thais [dissertation]. Adelaide, SA: University of Adelaide; 2002.

Sutthajunya C. Factors related to the exercise behaviors of Rajabhat institutes undergraduate students in Bangkok Metropolis [master’s thesis]. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University; 2003.

Suwanachaiy S. Six minute walk test in healthy persons with sufficient and insufficient levels of physical activity [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn, University; 2007.

Teparatana C. Factors predicting exercise behaviors in lower secondary school students [master’s thesis]. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Graduate School, Chiang Mai University; 1997.

Thanakwang K. Social relationships influencing positive perceived health among Thai older persons: A secondary data analysis using the National Elderly Survey. Nurs Health Sci. 2009;11(2):144–9.

Thasanasuwan W, Srichan W, Kijboonchoo K, Yamborisut U, Wimonpeerapattana W, Rojroongwasinkul N, et al. Low sleeping time, high TV viewing time, and physical inactivity in school are risk factors for obesity in pre-adolescent Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99(3):314–21.

Thavillarp P. Health beliefs and exercise behavior among health science students Chiang Mai University [master’s thesis]. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Graduate School, Chiang Mai University; 2004.

Triprakong S, Sangmanee W, Thavalphasit K. Factors Influencing Exercise Behavior of Nursing Department Personnel in Songklanagarind Hospital. J Faculty Nurs Burapha University. 2012;20(2):75–92.

Vannarit T. Predictors of exercise activity among rural Thai older adults [dissertation]. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama at Birmingham; 1999.

Vathesatogkit P, Sritara P, Kimman M, Hengprasith B, E-Shyong T, Wee HL, et al. Associations of Lifestyle Factors, Disease History and Awareness with Health-Related Quality of Life in a Thai Population. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49921.

Voraroon S, Phosuwan A, Jaiyangyeun U, Bunyasit P. The predictors of exercise behavior among health volunteers, Sanamchai, Mueng district, Suphanburi provice. J Nurs Educ. 2011;4(1):52–61.

Wakabayashi M, McKetin R, Banwell C, Yiengprugsawan V, Kelly M, Sam-ang S, et al. Alcohol consumption patterns in Thailand and their relationship with non-communicable disease. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2662-9.

Wannasuntad S. Factors predicting Thai children's physical activity [dissertation]. San Francisco, CA: University of California, San Francisco; 2007.

Watcharathanakij S, Moolasarn S, Phanritdam S, Noobome M. Physical Exercise Behavior of Ubon Ratchathani University Undergraduate Students. Isan J Pharm Sci. 2012;8(3):35–47.

Wattanapisit A, Fungthongcharoen K, Saengow U, Vijitpongjinda S. Physical activity among medical students in Southern Thailand: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013479. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013479.

Wattanapisit A, Gaensan T, Anothaisintawee T. Prevalence of physical activity and associated factors of medium and high activity among medical students at Ramathibodi Hospital. Paper presented at: The 6th International Conference on Sport and Exercise Science; 2015 Jun 24-26; Chonburi, Thailand.

Wattanasirichaigoon S, Polboon N, Ruksakom H, Boontheaim B, Sithisarankul P, Visanuyothin T. Thai physicians' career satisfaction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(Suppl 4):S5–8.

Wattanasit P. Determinants of physical activity in Thai adolescents: Testing the youth physical activity promotion model [dissertation]. Songkla, Thailand: Nursing (International Program), Prince of Songkla University; 2009.

Wichaidit W, Sangthong R, Chongsuvivatwong V, McNeil E, Chariyalertsak S, Kessomboon P, et al. Religious affiliation and disparities in risk of non-communicable diseases and health behaviours: Findings from the fourth Thai National Health Examination Survey. Global Public Health. 2014;9(4):426–35.

Yamchanchai W. The relationship between perceived self-efficacy, perceived health status and health-promoting behaviors in elderly persons [master’s thesis]. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Faculty of Graduate School, Mahidol University; 1995.

Yiammit C. The study of exercise behavior of Rambhai Barni Rajabhat in academic year 2010 [master’s thesis]. Bangkok, Thailand: Graduate School, Srinakharinwirot University; 2013.

Youngpradith A, Gretebeck KA, Charoenyooth C, Phancharoenworakul K, Vorapongsathorn T. A causal model of promoting leisure-time physical activity among middle-aged Thai women. Thai J Nurs Res. 2005;9(1):49–62.

เงินทอง ว, ทองวินิชศิลป์ เ, เงินทอง ก. ปัจจัยที่มีอิทธิพลต่อพฤติกรรมการออกกำลงกาย ของสมาชิกชมรมสร้างสุขภาพจังหวัดสุโขทัย [Factors affecting exercising behavior of member in the health promotion clubs, Sukho Thai province]. วารสารวิชาการ สถาบันการพลศึกษา. [Academic Journal Institute of Physical Education]. 2014;6(2):51–63.

เชยชม ก. พฤติกรรมการออกกำลังกายของนักเรียนประถมศึกษาในจังหวัดกระบี่ [Exercise behavior of pupils in Krabi province]. วารสารวิชาการ สถาบันการพลศึกษา[Academic Journal Institute of Physical Education]. 2015;7(1):29–38.

ชลานุภาพ บ. การศึกษาความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างทัศนคติในการดูแลสุขภาพกับพฤติกรรม การออกกำลังกายของบุคคลวัยทำงานในเขตกรุงเทพมหานคร [A study of the association between attitude of healthcare and exercise behavior of working adults in Bangkok metropolitan [master’s thesis]]. Bangkok: Graduate School, Bangkok University; 2009.

ทองสุขนอก จ, ธีระวิวัฒน์ ม, อิมามี น. ปัจจัยที่มีผลต่อพฤติกรรมการออกกำลังกายของผู้สูงอายุ ชมรมผู้สูงอายุ โรงพยาบาลเจริญกรุงประชารักษ์ [Factors associated to exercise behaviors of elderly, elderly club, Charoenkrunk Pracharak hospital]. วารสารสุขศึกษา [Journal of Health Education]. 2008;31(110):107–23.

นาคะ ข, ตะบูนพงศ์ ส, คู่พันธวี เ. สถานการณ์การออกกำลังกายของผู้สูงอายุในจังหวัดสงขลา [Exercise situation of the elderly in Songkla province]. Songkla, Thailand; 2002.