Abstract

Background

The way how technology addiction relates to psychosis remains inconclusive and uncertain. The present study aimed to test the hypothesis of a mediating role of depression, anxiety and stress in the association between three technology (behavioral) addictions (i.e., Addiction to the Internet, smartphones and Facebook) and psychosis proneness as estimated through schizotypal traits in emerging adults.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed among non-clinical Tunisian university students (67.6% females, mean age of 21.5 ± 2.5 years) using a paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire.

Results

Results for the Pearson correlation revealed that higher smartphone, Internet, and Facebook addictions’ scores were significantly and positively correlated with each of the depression, anxiety and stress subscores; whereas depression (r = 0.474), anxiety (r = 0.499) and stress (r = 0.461) scores were positively correlated with higher schizotypal traits. The results of the mediation analysis found a significant mediating effect for depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms on the cross-sectional relationship between each facet of the TA and schizotypal traits.

Conclusion

Our findings preliminarily suggest that an addictive use of smartphones, Internet and Facebook may act as a stressor that exacerbates psychosis proneness directly or indirectly through distress. Although future longitudinal research is needed to determine causality, we draw attention to the possibility that treating psychological distress may constitute an effective target of interventions to prevent psychosis in adolescents with technology addictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of smartphone owners has been on a constant rise over the last six years, from 49% of the world’s population in 2016 to 83% in 2022 [1]. Smartphones provide easy, practical, and non-restricted access to many online services, with approximately three-quarters of Internet users accessing the Internet exclusively via smartphones by 2025 [2]. One of the most popular daily activities on the Internet is interaction with various social media platforms. These platforms include (but are not limited to) Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, Tiktok, Twitter, Snapchat, the specifics depending on geographical region.

The amount of time Internet users spend on social media has also been increasing and has reached 144 min per day, an increase of more than 30 min/day since 2015 [3]. Such use has the potential of becoming rapidly addictive [4,5,6,7]; it has consequently been categorized as a new-era pandemic [8] and, in some countries, has become a public health problem [9]. In Tunisia, a substantial proportion of adolescents and young adults are reported at risk of internet [10,11,12,13], smartphone [14], and social media [15, 16] addiction.

Growing evidence supports the negative effects of the addictive use of digital technology on human physical and mental health. Being an addict to technology has repercussions on a youth’s abilities and habits, as well as on his/her social behavior [17]. It interferes with daily activities, school work, and academic performance [18,19,20,21]. Importantly, technology addiction (TA) negatively influences users’ emotional and social functioning [22,23,24,25,26], and correlates with the presence of psychopathologies such as depression, anxiety [22, 27, 28], insomnia [29], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and social anxiety disorder [4, 30]. However, although TA has been extensively investigated in relation to a wide range of mental health problems [15, 31, 32], there has been very little research thus far on how such addictions may influence the development of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders [33,34,35,36,37]. Most of the literature on the relationship between TA and psychosis risk has been based on case reports documenting an emergence of psychosis during withdrawal from internet addiction (e.g., [38,39,40]).

The relationship between TA and schizotypy

Schizotypy refers to a latent personality organization that manifests in several underlying subthreshold positive and negative psychotic symptoms, together with interpersonal difficulties [41]. Schizotypy is considered a potential precursor to formal schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis [42], thus offering a unique insight into the nature of the relationship between the behavioral TA and psychosis-proneness. A limited but increasing amount of studies suggests a potential link between TA and attenuated psychosis indicators among non-clinical youth, such as pre-psychotic symptoms [40, 43], brief psychotic episodes [16, 40, 44], high psychoticism scores [45], and schizotypal personality disorders [46, 47]. Recently, Massaro et al. [48] demonstrated a positive relationship between problematic technology use and schizotypal (mainly disorganized) trait levels among undergraduate students. Truzoli et al. [47] also highlighted associations between certain schizotypal traits (i.e., introverted anhedonia, impulsive nonconformity) and Internet addiction. Both schizotypy and TA share a myriad of characteristics, such as social anhedonia [49, 50], interpersonal deficits [32, 51, 52], impulsivity [53, 54], a propensity toward magical thinking [55, 56], and cognitive perceptual experiences [57, 58]. A recent study found that persisting patterns of problematic technology use was positively associated with an elevation of subthreshold psychotic symptoms over time, suggesting TA as “a new environmental stressor” contributing to the etiology of psychosis [33].

Depression, anxiety, and stress as mediators between TA and schizotypy

There is increasing evidence that TA is positively related to self-perceived psychological distress [59,60,61,62]. At the same time, psychological distress has been found to be significantly linked to elevated psychosis risk, attenuated psychosis syndromes, and a heightened risk of transition from these to diagnosable psychosis [63, 64]. One hypothetical route from TA addiction to psychosis is the incursion of addiction into the time and energy needed to succeed in academic/professional tasks and interpersonal relationships. This, in turn, can lead to psychological distress and subsequent raise in psychosis risk [65]. Untreated psychopathology may add additional vulnerability to young adults with TA, and can be regarded as “a perpetuating risk of psychosis” [40]. To further explore the pathways between TA and psychosis, we hypothesized that psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress) mediates the relationship between TA and schizotypal traits. A literature search revealed that scant research attention has been given to understanding the nature and the mediating factors in the relationship between TA specifically and psychosis proneness.

Rationale and objectives of the present study

Exploring the interplay between behavioral addictions, psychological distress, and psychosis in young adults is relevant, given that this age group represents people at the peak of the onset of this psychopathology [66]. Additionally, today’s young adults are first exposed to technology at an early age and, thus, by adolescence, have been addicted for many years [67, 68]. Globally, nine out of ten youths report daily use of online activities [69], with smartphones and social media being preferred above all else [70,71,72]. Despite the available data, it is not known how TA can result in mental illness, psychosis in particular [73]. Investigating the mediating factors between TA and proneness to psychosis, as evidenced by the presence of schizotypal traits in adolescents may assist in designing effective intervention.

In this context, the present study aimed to test the hypothesis of a mediating role of psychological distress (depression and anxiety) in the association between three technology (behavioral) addictions (i.e., addiction to the Internet, smartphones, and Facebook) and the presence of schizotypal traits among non-clinical Tunisian university students. By researching different dimensions of TA (tech hardware, smartphone; tech software, Internet, and Facebook), we aim to provide a complete overview of how each dimension relates to schizotypy. In addition, by investigating all three psychological distress dimensions, we aim to offer a complete and thorough description of how each of these distress factors may serve as intermediaries between TA and schizotypy.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This is a cross-sectional study of Tunisian students enrolled at public universities in 2021–22. Eligibility criteria to participate were: age 18 or older, no personal history of psychosis, and no exposure to antipsychotic drugs. To be included, students needed to own a smartphone, have access to the Internet and a Facebook account. Participants were selected using convenience sampling over a three-month period (October-December 2021). A total of 745 students agreed to participate and provided informed written consent. After excluding incomplete questionnaires, 700 responses were used in the final analysis.

Questionnaire

A paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaire was used, containing two sections. The first section covered sociodemographic information, including age, gender, living arrangement, place of residence, and monthly family income. To evaluate the extent of participants’ smartphones, Internet, Facebook addictions, psychological distress, and schizotypal traits, the questionnaire included the following screening instruments in the second section:

The Smartphone Addiction Scale – Short Version (SAS-SV, [74])

This is a 10-items research tool representing a shortened version of the original 33-items scale [75]. A total score is obtained by summing the items and ranges from 10 to 60. Higher scores point to an increased risk of smartphone addiction. The Arabic SAS-SV that we used in our study has good psychometric properties [76] and showed adequate internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88).

The Internet Addiction Test (IAT, [77, 78])

The IAT is a 20-item measure used to evaluate dysfunctional Internet usage through probing feelings, productivity, social life, and sleeping pattern. The 5-point Likert scale yields total scores ranging from 20 to 100, with higher scores suggesting greater Internet addiction. The Arabic IAT employed in this study has good internal consistency [79] and revealed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89 in the present study.

The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS, [80])

The BFAS is a 5-point Likert-type 6-item scale, widely used to assess the six following features and symptoms of Facebook addiction: mood modification, conflict, salience, tolerance, withdrawal, and relapse [81]. Total scores may reach a maximum of 30, with higher scores indicating increased Facebook addiction. We utilized the Arabic version of the BFAS (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) [82], which has shown to reliability in our sample (alpha = 0.84).

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21, [83])

This consists of a 21-item measure used to assess the severity of psychological distress symptoms and is divided into three subscales: DASS-depression (7 items), DASS-anxiety (7 items), and DASS-stress (7 items). The DASS-21 is a four-point Likert-type scale (from “I strongly disagree” = 0 to “I totally agree” = 3), with higher scores in each subscale referring to greater distress. The Arabic DASS-21 [84] showed good reliability in this study, with Cronbach’s alpha for the total DASS-21 score of 0.93.

The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ, [85])

The SPQ is a 74-item used to examine schizotypal traits and symptoms. It includes nine dimensions (i.e. Ideas of reference, paranoid ideation/suspiciousness, odd beliefs or magical thinking, unusual perceptual experiences, lack of close friends, excessive social anxiety, odd or eccentric behavior, odd speech, and constricted affect), divided into three subscales (i.e. positive, negative, disorganized). The higher the score, the more schizotypy features. The Arabic version of the SPQ [86] yielded good reliability with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.91 for the total score (74 items).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 26.0 for windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Shapiro–Wilk test revealed a normal distribution of data. Descriptive statistics were performed for the sociodemographic data. Then, the correlations between the SAS-SV, IAT, BFAS, DASS-21, and SPQ scores were evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. Subsequently, mediation analyses were used to test the indirect effects of psychological distress in the relationship between each aspect of the TA (smartphone, Internet, and Facebook addictions) as independent variables and schizotypy as the dependent (outcome) variable. We conducted generalized linear models (GLM) equations for each distress dimension in predicting its mediation on the relationships between smartphone addiction-schizotypy, Internet addiction-schizotypy, and Facebook addiction-schizotypy, respectively. According to the models built, we hypothesized that: (1) The three independent variables (smartphone, Internet, and Facebook addictions) would affect the mediator variables (depression, anxiety, and stress) in the first equation, (2) smartphone, Internet and Facebook addictions would affect the outcome variable (schizotypy total scores) in the second equation; and (3) The three mediators (depression, anxiety, and stress scores) would affect schizotypy scores in the third equation. We also hypothesized that the effect of TA on schizotypal traits would be smaller in the third equation as compared to the second one.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants were mostly females (67.6%), and had a mean age of 21.5 ± 2.5 years. More than half of the participants lived with their parents (57.4%), and the majority were from urban areas (87.3%). Further sociodemographic information is displayed in Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficient analysis

Results for the Pearson correlation between study variables are presented in Table 2. Higher smartphone, Internet, and Facebook addictions’ scores were significantly and positively correlated with each of the depression, anxiety and stress subscores; and depression (r = 0.474), anxiety (r = 0.499) and stress (r = 0.461) scores were positively correlated with higher schizotypal traits.

Mediation analyses: direct and indirect associations of TA with schizotypy

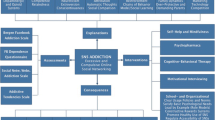

The results of the mediation analysis found a significant mediating effect for depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms on the relationship between each facet of the TA and schizotypal traits (Fig. 1).

The estimation of the direct and indirect effects of depression, anxiety and stress between TA and schizotypy. Each line is labeled with effects estimate and their 95%- confidence intervals. IAT: Internet Addiction Test; BFAS: Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale; SAS-SV: Smartphone Addiction Scale –Short Version; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales; SPQ: Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

This work focused on elucidating cross-sectional relationships between TA and schizotypy in samples of non-clinical emerging adults and deepening knowledge about the nature of the interaction between these variables on psychological distress (the mediator variable). The main finding was that, as expected, the mediation paths revealed that depression, anxiety, and stress played a significant indirect role in the association between each TA facet investigated and schizotypal traits.

Findings showed that the relationships between each independent variable (i.e., smartphone, Internet and Facebook addictions) and the dependent variable (i.e., schizotypy) were significant. These results are in agreement with previous literature that showed that excessive digital technology use relates to a wide range of psychopathology symptoms and manifestations, including attenuated psychotic symptoms [16, 40, 43, 44] and schizotypal personality traits and disorders [46,47,48]. TA has even been suggested by some authors as an environmental risk factor that interacts with genetic vulnerability to “cause” psychosis [33, 38,39,40]. Indeed, the recent literature has documented a link between Internet addiction and substantial structural brain changes [87] in regions closely associated with subclinical psychotic symptoms [88]. This might suggest that changes in a developing brain made vulnerable by TA confer an elevated risk of psychosis development by harming analogous brain pathways. Furthermore, a genetic link between TA and psychosis is also possible. A specific polymorphism in the CHRNA4 gene (gene coding for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 4, rs1044396) has been identified in individuals presenting with internet addiction [89], and a similar profile of genetic polymorphisms has been found in schizophrenia [90]. In addition, the serotonin genotype 5-HTTLPR (short alleles of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region) has been identified in Internet addiction [91] and schizophrenia [92]. Other explaining mechanisms of the relationship between TA and psychosis can be hypothesized, including negative cognitions about the self and world (e.g., beliefs that one is more valuable online than offline or that the real world is unsafe compared to the world online), which have been reported in both TA [93, 94] and psychosis [95, 96]. We are aware, however, that although we have demonstrated a significant cross-sectional relationship between TA and schizotypy, longitudinal studies are still needed before any causal conclusions can be drawn. It is plausible that the association between these two variables is bidirectional, and that highly schizotypal individuals are more prone to show behavioral addictions in comparison to healthy people. Indeed, people with high schizotypy have certain traits that may increase their vulnerability to develop TA, such as excessive social anxiety [97], having poor social support and no close friends [98]. We thus urge readers to interpret our results with caution.

Overall, these data suggest that the interaction between TA and psychosis is rather complex, and likely underpinned by several factors and mechanisms. Hence the importance of further exploring the pathways linking TA to psychosis and psychosis vulnerability by considering potential mediators. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show that depression, anxiety and stress can act as mediators in the cross-sectional association between TA and schizotypy among non-clinical emerging adults. Our findings are consistent with the evidence of the previously established positive association between TA and psychological distress on the one hand [59,60,61,62, 99, 100], and between distress and schizotypy symptoms on the other [101, 102]. These data, along with our findings, suggest that the relationship between TA and schizotypy is not only direct but is also mediated by the action of psychological distress. Therefore, the presence of depression, anxiety and stress, either as a result of excessive digital technology use or as pre-existing conditions [103], partially explains the relationship between TA and schizotypy. In other words, the various forms of TA examined in this study might have been associated with more severe symptoms of schizotypy through symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress.

However, again, we are aware that our findings should be interpreted cautiously because of the study’s limitations. The cross-sectional research design of our study can say nothing definitive about causality. Future prospective longitudinal research studies are needed. Secondly, despite the use of psychometrically valid and reliable measures, the self-report nature of our survey questions its accuracy. Thirdly, while three aspects of TA, namely smartphones, the Internet, and Facebook, have been considered in this study, the latter aspect was assessed only in reference to the Facebook platform. Participants who mainly have used other platforms (e.g., Instagram, YouTube) and Facebook non-users were omitted from this study, limiting its representativeness of Tunisian youth. Participants were mainly women; it is possible that the results may not speak as accurately for men. Youth from other cultures and geographical regions may also not be represented.

Study implications

Although preliminary, the present research shows that all three facets of TA are strongly and positively associated with schizotypy among non-clinical emerging adults. It is hoped that these results will help parents, educational institutions, clinicians, and researchers understand the effects of TA on young individuals vulnerable to psychosis. Previous longitudinal research [33] found that continued problematic technology use was associated with persistence and worsening of psychotic symptoms and experiences, whereas discontinuation of usage was followed by a significant improvement in symptoms. This only preliminarily supports previous conclusions that technology addiction may, like cannabis use at this time of life, serve as an environmental stressor that “unmasks the subtle vulnerability” to psychosis [33] as per the diathesis-stress model of psychosis [104]. Previous data combined with our findings draw attention to the possibility, and likely benefits, of considering TA as a target for prevention and early intervention in psychosis. Until now, the development and implementation of prevention and intervention strategies for technology-related addictions have been addressed poorly in empirical research. A few psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy [105], and mindfulness techniques [106] have shown positive results for TA, but these and other psychotherapies need more serious study.

This study provides initial evidence that depression, anxiety, and stress may serve as strong mediators in the relationship between TA and schizotypal traits. Consequently, treating psychological distress may constitute an effective target for intervention and prevention of psychosis in adolescents with TA. Technology-based interventions for psychosis prevention (e.g., web-based psycho-education, integrated web-based therapy, web-based CBT, text messaging interventions, social networking, and peer and expert moderation) [107] may be highly acceptable, relevant, and feasible form of reaching youth.

Conclusion

By testing the mediating paths between TA and schizotypy, this study provides data that have not been researched before. The findings of this study in Tunisian university undergraduates has revealed a significant mediating role of depression, anxiety and stress in the cross-sectional relationship between TA and schizotypy. This preliminarily supports prior assumptions that the addictive use of smartphones, the Internet, and Facebook at vulnerable ages, when brain circuits are still being developed, may act as a stressor that directly or via psychological distress, can increases the risk for psychosis. This deserves the attention of parents, educators, counselors, and clinicians working in early intervention services. Finally, although the current findings are suggestive, they must be considered preliminary until further research is able to longitudinally replicate the association between TA and schizotypy.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to the privacy of the participants' identities. The dataset supporting the conclusions is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Turner A. How Many Smartphones Are in the World? 2020. 2021. https://www.bankmycell.com/blog/how-many-phones-are-in-the-world. Accessed 21 May 2021.

Handley L. Nearly three quarters of the world will use just their smartphones to access the internet by 2025. CNBC TV. 2019.

Dixon S. Number of global social network users 2018-2027. 2022.

Ko C-H, et al. The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):1–8.

Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(2):175–84.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(9):3528–52.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):311.

Block JJ. Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):306-7.

Jeri-Yabar A, et al. Association between social media use (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook) and depressive symptoms: Are Twitter users at higher risk? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;65(1):14–9.

Ben Thabet J, et al. Factors associated with Internet addiction among Tunisian adolescents. Encephale. 2019;45(6):474–81.

Mellouli M, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Internet Addiction among College Students in Sousse, Tunisia. J Res Health Sci. 2018;18(1):e00403.

Haddad C, et al. Association of problematic internet use with depression, impulsivity, anger, aggression, and social anxiety: Results of a national study among Lebanese adolescents. Pediatr Investig. 2021;5(4):255–64.

Dib JE, et al. Factors associated with problematic internet use among a large sample of Lebanese adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):148.

Halayem S, et al. The mobile: a new addiction upon adolescents. Tunis Med. 2010;88(8):593–6.

Amara A, et al. Addictions and mental health disorders among adolescents: a cross-sectional study; Tunisia 2020. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(Supplement_5):ckaa166-1068.

Fekih-Romdhane F, Sassi H, Cheour M. The relationship between social media addiction and psychotic-like experiences in a large nonclinical student sample. Psychosis. 2021;13(4):349–60.

Stanton J. Web addict or happy employee? Company profile of the frequent Internet user. Commun ACM. 2002;45(1):55–9.

Yoo HJ, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(5):487–94.

Chou C, Hsiao M-C. Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students’ case. Comput Educ. 2000;35(1):65–80.

Nalwa K, Anand AP. Internet addiction in students: A cause of concern. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6(6):653–6.

Tsai C-C, Lin SS. Internet addiction of adolescents in Taiwan: An interview study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6(6):649–52.

Shapira NA, et al. Problematic internet use: proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17(4):207–16.

Malaeb D, et al. Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: Any mediating effect of stress? Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):539–49.

Awad E, Hallit R, Haddad C, Akel M, Obeid S, Hallit S. Is problematic social media use associated with higher addictions (alcohol, smoking, and waterpipe) among Lebanese adults?. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021.

Barbar S, et al. Factors associated with problematic social media use among a sample of Lebanese adults: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(3):1313–22.

Dagher M, et al. Association between problematic social media use and memory performance in a sample of Lebanese adults: the mediating effect of anxiety, depression, stress and insomnia. Head Face Med. 2021;17(1):6.

Iftene F, Roberts N. Internet use in adolescents: hobby or avoidance. Can J Psychiat. 2004;49(11):789.

Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive Internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010;43(2):121–6.

Cheung LM, Wong WS. The effects of insomnia and internet addiction on depression in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents: an exploratory cross-sectional analysis. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(2):311–7.

Yen J-Y, et al. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(1):93–8.

Huang C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(1):12–33.

Hao Q.-H, et al. The Correlation Between Internet Addiction and Interpersonal Relationship Among Teenagers and College Students Based on Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:818494.

Mittal VA, Dean DJ, Pelletier A. I nternet addiction, reality substitution and longitudinal changes in psychotic-like experiences in young adults. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7(3):261–9.

Torous J. 152. Technology and Smartphone Ownership, Interest, and Engagement Among Those with Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(9):S62.

Torous J, et al. Patient Smartphone Ownership and Interest in Mobile Apps to Monitor Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions: A Survey in Four Geographically Distinct Psychiatric Clinics. JMIR Ment Health. 2014;1(1):e5.

Ben-Zeev D, et al. Mobile technologies among people with serious mental illness: opportunities for future services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):340–3.

Bao Y, Pincus HA. The Three-Part Model to Pay for Early Interventions for Psychoses. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):764.

Paik A, Oh D, Kim D. A case of withdrawal psychosis from internet addiction disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11(2):207.

Mendhekar DN, Chittaranjan AC. Emergence of psychotic symptoms during Internet withdrawal. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66(2):163–163.

Tzang RF, Chang CH, Chang YC. Adolescent’s psychotic-like symptoms associated with Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(6):384–384.

Claridge GE. Schizotypy: Implications for illness and health. Oxford University Press; 1997.

Flückiger R, et al. Psychosis-predictive value of self-reported schizotypy in a clinical high-risk sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(7):923–32.

Rizzo A, Della Villa L, Crisi A. Can the Problematic Internet Use evolve in a pre-psychotic state? A single case study with the Wartegg. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;51:532–8.

Lee J-Y, et al. Negative life events and problematic internet use as factors associated with psychotic-like experiences in adolescents. Front Psych. 2019;10:369.

Cao F, Su L. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: prevalence and psychological features. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33(3):275–81.

Mittal VA, Tessner KD, Walker EF. Elevated social Internet use and schizotypal personality disorder in adolescents. Schizophr Res. 2007;94(1–3):50–7.

Truzoli R, et al. The relationship between schizotypal personality and internet addiction in university students. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;63:19–24.

Massaro D, Nitzburg G, Dinzeo T. Schizotypy as a predictor for problematic technology use in emerging adults. Curr Psychol. 2022. pp. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02700-3.

Barkus E, Badcoc J.C. A transdiagnostic perspective on social anhedonia. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:216.

Guillot CR, et al. Longitudinal Associations between Anhedonia and Internet-Related Addictive Behaviors in Emerging Adults. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;62:475–9.

Aghvinian M, Sergi MJ. Social functioning impairments in schizotypy when social cognition and neurocognition are not impaired. Schizophrenia research Cognition. 2018;14:7–13.

Yang S.Y, et al. Does Smartphone Addiction, Social Media Addiction, and/or Internet Game Addiction Affect Adolescents’ Interpersonal Interactions? Healthcare (Basel. 2022;10(5):963.

Cerniglia L, et al. The use of digital technologies, impulsivity and psychopathological symptoms in adolescence. Behav Sci. 2019;9(8):82.

Badoud D, et al. Encoding style and its relationships with schizotypal traits and impulsivity during adolescence. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):1020–5.

Elek Z, et al. Magical thinking as a bio-psychological developmental disposition for cognitive and affective symptoms intensity in schizotypy: Traits and genetic associations. Personality Individ Differ. 2021;171:110498.

Rosen LD, et al. The media and technology usage and attitudes scale: An empirical investigation. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(6):2501–11.

Leung L. Generational differences in content generation in social media: The roles of the gratifications sought and of narcissism. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(3):997–1006.

Locatelli SM, Kluwe K, Bryant FB. Facebook use and the tendency to ruminate among college students: Testing mediational hypotheses. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 2012;46(4):377–94.

Ho RC, et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:183.

Yang J, et al. Association of problematic smartphone use with poor sleep quality, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112686.

Yoon S, et al. Is social network site usage related to depression? A meta-analysis of Facebook–depression relations. J Affect Disord. 2019;248:65–72.

Marino C, et al. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274–81.

Fusar-Poli P, et al. Comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders in 509 individuals with an at-risk mental state: impact on psychopathology and transition to psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):120–31.

Devylder J, et al. Temporal association of stress sensitivity and symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):259–68.

Henzel V, Håkansson A. Hooked on virtual social life. Problematic social media use and associations with mental distress and addictive disorders. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0248406.

Solmi M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281–95.

Griffiths MD. Social Networking Addiction: Emerging Themes and Issues. J Addict Res Ther. 2013;4:e118.

Shin J. Teenagers peer relationship stress, academic stress, stress coping, effects of smartphone addiction (master’s thesis). Kyungju: Dongguk University; 2015. p. 1–74.

Statista. Global Gen Z Online Activity Reach by Device 2018. 2019.

O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800–4.

Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use among Teens and Young Adults. Millennials. Pew internet & American life project. 2010.

Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. 2018;2018(31):1673–89.

Orben A, Przybylski AK. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat Hum Behav. 2019;3(2):173–82.

Kwon M, et al. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83558.

Kwon M, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56936.

Zeidan J, et al. Problematic smartphone use and affective temperaments among Lebanese young adults: scale validation and mediating role of self-esteem. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):136.

Young KS. Internet addiction test. Center for on-line addictions. 2009.

Young KS. Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of internet addiction--and a winning strategy for recovery. John Wiley & Sons; 1998.

Hawi NS. Arabic validation of the Internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(3):200–4.

Andreassen CS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501–17.

Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance use. 2005;10(4):191–7.

Ghali H, Ghammem R, Zammit N, Fredj SB, Ammari F, Maatoug J, Ghannem H. Validation of the Arabic version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale in Tunisian adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2022;34(1).

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43.

Antony MM, et al. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998;10(2):176.

Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(4):555–64.

Mohamed AL, et al. Psychometric properties of the arabic version of the schizotypal personality questionnaire in Tunisian university students. Tunis Med. 2014;92(5):318–22.

Yuan K, et al. Microstructure abnormalities in adolescents with internet addiction disorder. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20708.

Jacobson S, et al. Structural and functional brain correlates of subclinical psychotic symptoms in 11–13 year old schoolchildren. Neuroimage. 2010;49(2):1875–85.

Montag C, et al. The role of the CHRNA4 gene in Internet addiction: a case-control study. J Addict Med. 2012;6(3):191–5.

Li YY, et al. Association Study of Polymorphisms in Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Genes With Schizophrenia in the Han Chinese Population. Psychiatry Investig. 2021;18(10):943–8.

Pardiñas AF, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50(3):381–9.

Ghamari R, et al. Serotonin transporter functional polymorphisms potentially increase risk of schizophrenia separately and as a haplotype. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1336.

Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(5):1089–97.

Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2001;17(2):187–95.

Kesting ML, Lincoln TM. The relevance of self-esteem and self-schemas to persecutory delusions: a systematic review. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):766–89.

Taylor CDJ, et al. Characterizing core beliefs in psychosis: a qualitative study. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2020;48(1):67–81.

Lee-Won RJ, Herzog L, Park SG. Hooked on Facebook: The role of social anxiety and need for social assurance in problematic use of Facebook. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(10):567–74.

Meshi D, Ellithorpe ME. Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addict Behav. 2021;119:106949.

Elhai JD, et al. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:251–9.

Thomée S, Härenstam A, Hagberg M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults–a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:66.

Lewandowski KE, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in psychometrically identified schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(2–3):225–35.

Debbané M, et al. Cognitive and emotional associations to positive schizotypy during adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):326–34.

Lau JTF, et al. Bidirectional predictions between Internet addiction and probable depression among Chinese adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(3):633–43.

Walker E, Mittal V, Tessner K. Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:189–216.

Sharma MK, Palanichamy TS. Psychosocial interventions for technological addictions. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(Suppl 4):S541-s545.

Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths M. Practical tips for teaching mindfulness to children and adolescents in school-based settings. Educ Health. 2014;32(2):69–72.

Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophr Res. 2014;156(1):96–106.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all students who participated in this study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FFR designed the study. FFR and RA coordinated data collection, data entry and data cleaning. FFR and HJ performed statistical analyses and wrote the first draft. FFR, HJ, KT, SRP, MVS, SH and MC provided intellectual contributions to strengthening the manuscript and edited original draft. All authors provided critical revisions of manuscript, involved in writing and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Razi hospital, Manouba, Tunisia. Online informed consent to participate was obtained for all participants before survey initiation. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fekih-Romdhane, F., Jahrami, H., Away, R. et al. The relationship between technology addictions and schizotypal traits: mediating roles of depression, anxiety, and stress. BMC Psychiatry 23, 67 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04563-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04563-9