Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, suspension of visits by next of kin to patients in intensive care units (ICU), to prevent spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has been a common practice. This could impede established family-centered care and may affect the mental health of the next of kin. The aim of this study was to explore symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) in the next of kin of ICU patients.

Methods

In this prospective observational single-center study, next of kin of ICU patients were interviewed by telephone, using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), to assess symptoms of acute stress disorder during the ICU stay and PTSD symptoms at 3 months after the ICU stay. The primary outcome was the prevalence of severe PTSD symptoms (IES-R score ≥ 33) at 3 months. The secondary outcomes comprised the IES-R scores during the ICU stay, at 3 months, and the prevalence of severe symptoms of acute stress disorder during ICU stay. An inductive content analysis was performed of the next of kin’s comments regarding satisfaction with patient care and the information they were given.

Results

Of the 411 ICU patients admitted during the study period, 62 patients were included together with their next of kin. An IES-R score > 33 was observed in 90.3% (56/62) of next of kin during the ICU stay and in 69.4% (43/62) 3 months later. The median IES-R score was 49 (IQR 40–61) during the ICU stay and 41 (IQR 30–55) at 3 months. The inductive content analysis showed that communication/information (55%), support (40%), distressing emotions (32%), and suspension of ICU visits (24%) were mentioned as relevant aspects by the next of kin.

Conclusions

During the suspension of ICU visits in the COVID-19 pandemic, high prevalence and severity of both symptoms of acute stress disorder during the ICU stay and PTSD symptoms 3 months later were observed in the next of kin of ICU patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may develop after exposure to a single or multiple traumatic event(s) and/or prolonged traumatic event [1]. The published figures for life-time prevalence vary between 1.9 and 7.8% [2, 3].

The prevalence of clinically relevant PTSD symptoms among family members of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) has been estimated at 33 to 56% [4,5,6,7]. Sparse provision of family-centered care (e.g., timely provision of adequate information, involvement in decision-making, social and emotional support, next of kin’s abilities to provide care) in the ICU may play a crucial role in the development of PTSD symptoms [7]. Interventions to support next of kin of ICU patients during the ICU stay and there after often prove insufficient [8].

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 as a pandemic. Various measures, including social distancing, were introduced to reduce the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As recently shown, this pandemic has affected adult mental health; reports of the prevalence of clinically relevant PTSD symptoms range from 15.8 to 37.7% [9,10,11].

In many ICUs worldwide, visits were suspended to comply with social distancing requirements and prevent the spread of contamination among staff, patients, and next of kin. This practice may impede the provision of family-centered care in ICUs [12, 13]. Therefore, we hypothesize that patients’ next of kin may have been exposed to a higher risk of PTSD symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. This could have detrimental effects on health, social life, and working life [15].

We therefore set out to investigate the prevalence and experience of PTSD symptoms in the next of kin of ICU patients during suspension of ICU visits in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we interviewed next of kin of ICU patients by telephone, using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), to assess symptoms of acute stress disorder during the ICU stay and PTSD symptoms 3 months thereafter, with qualitative content analysis of their comments and experiences.

Methods

Study design

A prospective single-center study of the next of kin of ICU patients was performed at a tertiary academic center. The study was conducted in the interdisciplinary (medical/surgical) ICUs of the Department of Intensive Care Medicine at the Inselspital in Bern, Switzerland between March 16 and May 11, 2020. During this observation period, all hospital visits by next of kin were suspended to prevent spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 virus among staff, patients, and their family members. Exceptions were made for end-of-life visits.

Participants

The participants in this study were the next of kin of patients hospitalized in the ICU during the observation period. The exclusion criteria were patient/next of kin aged < 18 years; inability of next of kin to participate in a telephone interview due to insufficient knowledge of German, French, or Italian; refusal by next of kin to participate in the study; and failure to make contact with next of kin before patient’s discharge from the ICU.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee on Human Research, Bern, waived the requirement for ethics approval and the need to obtain consent for the collection, analysis, and publication of the data for this study (KEK Req-2020-00739). However, oral informed consent was obtained from the participating next of kin. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Outcome measures

In brief, for each individual patient who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study, the next of kin was identified at admission to the ICU. The next of kin who met the inclusion criteria were interviewed twice by telephone, to assess potential symptoms of acute stress disorder at 1–5 days after patient ICU admission and PTSD symptoms at 3 months after discharge from or death in the ICU (as defined in the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-5) [16].

The validated IES-R was used to estimate symptoms of acute stress disorder at day 1–5 [17,18,19] and PTSD symptoms after 3 months [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The IES-R is a 22-item questionnaire with three defined subscales (avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”), yielding a total score ranging between 0 (best) and 88 (worst). We chose an IES-R score of 33 as cut-off for severe PTSD symptoms, in line with previous studies [22, 24].

Family satisfaction in the ICU was assessed using an adapted version of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit 24-Item-Revised (FS-ICU 24R) questionnaire [27]. The questionnaire was adapted to the suspension of ICU visits by exclusion of questions that could not be answered without the physical presence of the next of kin in the ICU (see additional file 1). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale. The scale for items 1 to 8 ranged from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 5 (“completely satisfied”), while the scale for item 9 ranged from 1 (“I felt very excluded”) to 5 (“I felt very included”). The final score of the adapted FS-ICU 24R ranged from 9 (worst) to 45 (best). As proposed in the original scoring manual, responses on the adapted version were excluded whenever > 30% of items were missing (n = 9/62,14%) [28].

The patient data recorded included demographics, emergency admission, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), COVID-19 positivity, mechanical ventilation, length of stay, and death in the ICU. The demographics of the next of kin were also recorded. All data recorded are parameters that may contribute to symptoms of acute stress disorder and/or PTSD symptoms in the next of kin [7].

The primary outcome was the prevalence of severe symptoms of PTSD (defined as IES-R score > 33) among the next of kin at 3 months after patient discharge from the ICU (or death) [22, 24]. The secondary outcomes included the next of kin IES-R scores (range 0–88) at 3 months, the proportion with an prevalence of severe PTSD symptoms (IES-R score > 33,) and total IES-R score (0–88) during ICU stay.

Qualitative data

An inductive content analysis was performed on the next of kin’s comments and experience regarding general satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making [29]. This content analysis was embedded in the adapted FS-ICU 24R questionnaire, and data were used for hypothesis generation with regard to factors potentially contributing to symptoms of acute stress disorder, mental stress and PTSD symptoms. Two researchers (MMJ, KE) with experience in inductive content analysis evaluated the comments.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were computed as proportions; continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and standard deviation (SD), as appropriate. Normal distribution was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons of categorical variables between groups (defined by IES-R cut-off values) were performed with Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test or the t-test, as appropriate. The McNemar test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare IES-R categorical and continuous data between the ICU stay and the 3-month follow-up. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered to show a significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, 2017) and R (R Core Team, version 4.0.3).

If two or fewer answers were missing in the IES-R scale (n = 4 in the ICU survey, n = 3 in the 3-month survey) the missing responses were substituted using the person mean substitution method [30]. Data sets with three or more answers missing were excluded from analysis (n = 10).

Results

Study population

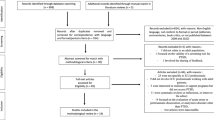

Of the 411 patients admitted to the ICU during the observation period, 62 patients and their next of kin were included in the study (Fig. 1). Among the 261 patients discharged prior to screening, 212 had an ICU stay of less than 24 h. The demographic characteristics of next of kin and patients are given in Tables 1 and 2. No differences in the demographic data of next of kin and patients were noted between the two IES-R groups (IES-R < 33 vs. IES-R > 33) during the ICU stay (Table 3). In addition, no differences in the demographic data of next of kin and patients were observed between the IES-R groups at 3 months’ follow-up, with the exception of admission to the ICU after surgery (p = 0.03; Table 4).

Prevalence of symptoms of acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms in next of kin of ICU patients during suspension of ICU visits

An IES-R score > 33 was observed in 90.3% (n = 56/62) of next of kin during the patients’ ICU stays and in 69.4% (n = 43/62) of next of kin 3 months after ICU discharge. The median IES-R score was 49 (IQR 40–61) in the ICU and 41 (IQR 30–55) at the 3-month follow-up (Table 1). A difference was observed between the frequency of severe symptoms of acute stress disorder (cut-off IES-R > 33) during the ICU stay (n = 56) and the frequency of severe PTSD symptoms at follow-up 3 months after discharge (n = 43; p = 0.001). The IES-R scores declined between the ICU stay and the 3-month follow-up (from 49 (IQR 40–61) to 41 (IQR 30–55); p < 0.0001).

Prevalence of symptoms of acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms in next of kin subgroups of next of kin

Overall, 43.6% (27/62) of the patients were admitted to the ICU following surgical interventions (Table 2). No differences were observed in patients’ admissions after emergency surgery comparing next of kin with IES-R score < 33 and IES-R score > 33 (IES-R score < 33 vs. IES-R score > 33; n = 2/4, 50%; n = 15/23, 65.2%, respectively, p = 0.61,) neither in the ICU nor at 3 months (n = 7/12, 58.3%; n = 10/15, 66.7%, respectively, p = 0.71).

Information on the educational level was available in 75.8% of the next of kin (n = 47/62). Higher educational level (higher training/ university degree) was found in 29.8% (n = 14/47). No difference was observed regarding IES-R score (< 33 or > 33) between next of kin with and those without higher educational training, neither in the ICU (n = 3/5, 60% vs. n = 11/42, 26.2%; p = 0.15) or at 3 months follow-up (n = 6/16, 37.5% vs. n = 8/31, 25.8%; p = 0.5).

Overall family satisfaction

Family satisfaction was assessed using an adapted version of the FS-ICU 24R, and a median score of 33 (IQR 28–40; Table 1) was observed. No differences were observed between the two IES-R groups (IES-R score < 33 vs. > 33) during ICU stay (p = 0.63; Table 3) or at 3 months (p = 0.9; Table 4). The distribution of answers on the adapted FS-ICU 24R is shown in Fig. 2.

Proportions of answers on the adapted FS-ICU 24R ordered by degree of agreement. Responses for items 1 to 8 were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 5 (“completely satisfied”), while the scale for item 9 ranged from 1 (“I felt very excluded”) to 5 (“I felt very included”)

Qualitative content analysis

Overall, 156 comments from the 62 next of kin were evaluated in an inductive content analysis. Four main categories of experiences were elaborated from their comments: (1) communication and information (n = 34/62, 55%); (2) support received (n = 25/62, 40%); (3) distressing emotions (n = 20/62, 32%); (4) suspension of ICU visits (n = 15/62, 24%).

Aspects of communication and information appeared most important to the next of kin. Positive feedback was associated with no limitations being placed on time, active telephone calls from ICU staff, frankness about the specific situation, avoidance of technical terminology, repetition of information, and establishment of the current state of knowledge at the beginning of conversations. Factors cited as reasons for negative experiences included language barriers, decreased comprehensibility, and constraints on time to talk with the patient.

With regard to support, the next of kin appreciated the availability of video telephone calls and/or provision of ICU diaries (which forms part of the institutional standard of family-centered care) including photographs and explanations of the patient’s status and specific ICU setting. Further, questions regarding the well-being of the next of kin and provision of information about daily ICU care and routines (e.g., mobilization, weaning trials, interventions) elicited positive comments.

In the third category, the next of kin highlighted distressing emotions related to the situation and reported feelings of anxiety, worry, and loneliness. As for the fourth category, suspension of ICU visits, some next of kin described the situation as “terrible” because they “lost contact with loved ones”. However, we noted that the next of kin attempted to cope with specific situations and the respective consequences, including suspension of ICU visits.

Discussion

In a single-center prospective study, we investigated the prevalence of symptoms of acute stress disorder during the ICU stay and PTSD symptoms 3 months thereafter among the next of kin of ICU patients during suspension of ICU visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We observed that the majority of the next of kin experienced severe symptoms of acute stress disorder during their family member’s ICU stay and severe PTSD symptoms afterwards. Previous studies had reported that the next of kin of ICU patients may experience symptoms of PTSD [7]; however, we observed potentially higher prevalence and greater severity of PTSD symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [4,5,6].

A number of factors may be responsible for potentially higher prevalence and severity of the symptoms of acute stress disorder/PTSD symptoms among the next of kin of ICU patients in this specific context. First, it appears that the COVID-19 pandemic itself induces PTSD [9,10,11]. Among other factors, uncertainty, confusion, and anxiety regarding infection and the social consequences may increase the likelihood of symptoms of acute stress disorder and/or PTSD symptoms [9, 11]. This “baseline” psychological distress may be increased in the next of kin of ICU patients [7], with potential augmentation of existing symptoms of acute stress disorder and/or PTSD symptoms [31, 32].

Other investigations have proposed that the risk of developing PTSD symptoms may be associated with particular demographic characteristics (e.g., female gender, age of next of kin and/or patient, educational level) [33,34,35]. In our study, however, no association between specific demographic data and the development of severe PTSD symptoms was observed. Further, levels of communication and information provision seemed to be risk factors for PTSD development [6, 36, 37]. Interestingly, despite good ratings for the next of kin’s satisfaction with regard to information provided, the prevalence and severity of PTSD symptoms among them remained high. This may imply that provision of information during the suspension of ICU visits meets the requirements of family-centered care [12].

Indeed, information can still be provided during suspension of ICU visits [13, 38, 39]. Other components of family-centered care can also be delivered in alternative ways at such a time [13, 14, 40]. However, the effects on symptoms of acute stress disorder/PTSD symptoms among next of kin remain unclear [8]. Indeed, inadequate provision of emotional support [41, 42] and insufficient communication regarding the patient’s prognosis [43, 44] and shared decision-making [45] may be related to PTSD symptoms. However, the importance of the physical presence of the next of kin for these specific family-centered care components remains unclear.

The qualitative data (inductive content analysis) may appear to imply that suspension of visits is challenging for next of kin. It is therefore tempting to speculate that suspension of ICU visits amplifies uncertainty regarding comfort and the specific patient situation in the ICU [6, 14, 46]. Investigations into liberal visiting policies in the ICU have revealed a positive impact on family satisfaction; however, the impacts on anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms remained unclear [47]. Hence, the content and context of the ICU visits may be crucial for coping with PTSD symptoms (avoidance of frustration, improvement of vigilance, reassurance, proximity, provision of information) [48, 49].

The next of kin’s symptoms of acute stress disorder may be explained by the exceptional situation due to the patients’ ICU stay. Importantly, this acute stress disorder should subside within days [50]. This may partly explain the decline of the IES-R score. However, despite a decline in the prevalence and severity of the PTSD stress symptoms relative to the time of the ICU stay, the respective IES-R scores remained high 3 months later. Certainly, the mental stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic seems to continue to this time. Likewise, the stress arising from ICU hospitalization may still be noticeable [4, 6]. These two factors appear to contribute to the severe PTSD symptoms in the next of kin of ICU patients [31, 32]. Notably, although the next of kin who exhibit transient symptoms of an acute stress disorder within days may not necessarily receive the diagnosis of PTSD after 3 month or later [51].

This study has several important limitations. The monocentric study design with a limited sample size and the imbalance between the groups compared may lead to a reduced external validity, especially in the context of family-centered care concepts. Nevertheless, the strengths of our study include the prospective design and the qualitative content analysis. Importantly, the IES-R is not suitable for the diagnosis of PTSD as defined in the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). To diagnosis PTSD, a clinician-administered structured clinical assessment is needed. Hence, in this study only symptoms of acute stress disorder and PTSDrelated symptoms could be estimated, with all the inherent limitations of a questionnaire. The IES-R was originally used to estimate PTSD symptoms [22]. Therefore, we used the IES-R, during the traumatic event (ICU hospitalization of a family member) for the sake of better comparability and progression of the symptoms among next of kin during and after the event [17,18,19]. This should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Moreover, no information was available on quarantine and/or isolation, which could theoretically impact on PTSD symptoms. However, the data on this topic remain controversial [9,10,11].

Furthermore, no data were available on the potential role of missing social support, which could affect PTSD symptoms [10, 52,53,54]. Also, despite good provision of information on the patients’ condition in the ICU, the impact of information about the COVID-19 pandemic, which itself could contribute to PTSD symptoms, should not be neglected [10]. Information on pre-existing psychological disorders and/or PTSD symptoms was not available for the next of kin; hence, the potential impact of any such factors remains unclear. In addition, our data show an imbalance in the gender distribution of the next of kin (more women), and previous studies indicate that women may be more susceptible to PTSD symptoms, both in general and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [9,10,11, 55, 56].

Conclusions

During the suspension of ICU visits in the COVID-19 pandemic, high prevalence and severity of both symptoms of acute stress disorder during the ICU stay and PTSD symptoms 3 months after discharge or death were observed in the next of kin of ICU patients. Additional investigations are required to investigate factors involved in PTSD and symptom development in the next of kin of ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, interventional strategies should be developed to provide specific support to next of kin both during and after the patient’s ICU stay.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and in its supplementary information file).

Abbreviations

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IES-R:

-

Impact of event scale-revised

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- KEK:

-

Kantonale ethikkommission (regional ethics committee)

- FS-ICU 24R:

-

Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit 24-item-revised

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- APACHE II:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified acute physiology score

References

Bisson JI, Cosgrove S, Lewis C, Robert NP. Post-traumatic stress disorder. BMJ. 2015;351:h6161.

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Lépine JP. The European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD) project: an epidemiological basis for informing mental health policies in Europe. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;s420(420):5–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00325.x.

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012.

Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Ingleby S, Eddleston J, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):456–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-2149-5.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–78. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa063446.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–94. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC.

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9.

Zante B, Camenisch SA, Schefold JC. Interventions in post-intensive care syndrome-family: a systematic literature review. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(9):e835–e40. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004450.

Traunmüller C, Stefitz R, Gaisbachgrabner K, Schwerdtfeger A. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 pandemic in the Austrian population. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09489-5.

González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos M, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:172–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040.

Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world: effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the italian population. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1802.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, et al. Guidelines for family-centered Care in the Neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169.

Azoulay E, Kentish-Barnes N. A 5-point strategy for improved connection with relatives of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30223-X.

Azoulay É, Curtis JR, Kentish-Barnes N. Ten reasons for focusing on the care we provide for family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;47(2):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06319-5.

Al-Saffar S, Borgå P, Hällström T. Long-term consequences of unrecognised PTSD in general outpatient psychiatry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(12):580–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0586-z.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2013.

Komachi M, Kamibeppu K. Acute stress symptoms in families of patients admitted to the intensive care unit during the first 24 hours following admission in Japan. Open J Nurs. 2015;5(4):325–35. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2015.54035.

Mongodi S, Salve G, Tavazzi G, Politi P, Mojoli F. High prevalence of acute stress disorder and persisting symptoms in ICU survivors after COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(5):616–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06349-7.

Pillai L, Aigalikar S, Vishwasrao SM, Husainy SM. Can we predict intensive care relatives at risk for posttraumatic stress disorder? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2010;14(2):83–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-5229.68221.

Motlagh H. Impact of event scale-revised. J Phys. 2010;56(3):203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70029-1.

Asukai N, Kato H, Kawamura N, Kim Y, Yamamoto K, Kishimoto J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(3):175–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200203000-00006.

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale - revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010.

Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2016;316(1):51–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8474.

Cox CE, Hough CL, Carson SS, White DB, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, et al. Effects of a telephone- and web-based coping skills training program compared with an education program for survivors of critical illness and their family members. A randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):66–78. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201704-0720OC.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Max A, Lerin T, Gregoire C, Ruckly S, Kloeckner M, et al. Impact of proactive nurse participation in ICU family conferences: a mixed-method study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1116–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001632.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Champigneulle B, Thirion M, Souppart V, Gilbert M, et al. Effect of a condolence letter on grief symptoms among relatives of patients who died in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(4):473–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4669-9.

Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland DK, Curtis JR. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the family satisfaction in the intensive care unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):271–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000251122.15053.50.

Critical Care Connections Inc., Scoring FS-ICU 24R, Queens: Critical Care Connections Inc.; [cited 2020 04.12.]. Available from: https://fsicu.org/wp-content/uploads/FS-ICU24R-Scoring-Instructions-.pdf.

Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse Weinheim Basel: Belz-Verlag; 2015, Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse.

Downey RG, King CV. Missing data in Likert ratings: a comparison of replacement methods. J Gen Psychol. 1998;125(2):175–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309809595542.

Suliman S, Mkabile SG, Fincham DS, Ahmed R, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Cumulative effect of multiple trauma on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(2):121–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.006.

Scott ST. Multiple traumatic experiences and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(7):932–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507301226.

Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2.

Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, Nielsen EL, Zatzick D, Curtis JR. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(4):795–801. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-0652.

Oliveira HSB, Fumis RRL. Sex and spouse conditions influence symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in both patients admitted to intensive care units and their spouses. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(1):35–41. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507x.20180004.

Black MD, Vigorito MC, Curtis JR, Phillips GS, Martin EW, McNicoll L, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve compliance with process measures for ICU clinician communication with ICU patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(10):2275–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182982671.

Kodali S, Stametz R, Clarke D, Bengier A, Sun H, Layon AJ, et al. Implementing family communication pathway in neurosurgical patients in an intensive care unit. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):961–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951514000650.

Mistraletti G, Umbrello M, Mantovani ES, Moroni B, Formenti P, Spanu P, et al. A family information brochure and dedicated website to improve the ICU experience for patients' relatives: an Italian multicenter before-and-after study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(1):69–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4592-0.

Kennedy NR, Steinberg A, Arnold RM, Doshi AA, White DB, DeLair W, et al. Perspectives on telephone and video communication in the ICU during COVID-19. Ann Am Thoracic Soc. 2020;18(5):838–47. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-729OC.

Zante B, Camenisch S, Jeitziner MM, Jenni-Moser B, Schefold JC. Fighting a family tragedy: family-centred care in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2020;52(4):336–8. https://doi.org/10.5114/ait.2020.100501.

Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, White DB. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1311–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8.

Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):844–9. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC.

Curtis JR, Ciechanowski PS, Downey L, Gold J, Nielsen EL, Shannon SE, et al. Development and evaluation of an interprofessional communication intervention to improve family outcomes in the ICU. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(6):1245–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.06.010.

White DB, Ernecoff N, Buddadhumaruk P, Hong S, Weissfeld L, Curtis JR, et al. Prevalence of and factors related to discordance about prognosis between physicians and surrogate decision makers of critically ill patients. Jama. 2016;315(19):2086–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.5351.

Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-1291.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1341–52. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00160014.

Nassar Junior AP, Besen B, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(7):1175–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003155.

Plost G, Nelson D. Family care in the intensive care unit: the Golden rule, evidence, and resources. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):669–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000254040.14921.26.

Slota M, Shearn D, Potersnak K, Haas L. Perspectives on family-centered, flexible visitation in the intensive care unit setting. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5 Suppl):S362–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000065276.61814.B2.

World Health O. ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems : tenth revision. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Bryant RA. Acute stress disorder as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):233–9. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09r05072blu.

Pinto RJ, Morgado D, Reis S, Monteiro R, Levendosky A, Jongenelen I. When social support is not enough: trauma and PTSD symptoms in a risk-sample of adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;72:110–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.017.

Price M, Lancaster CL, Gros DF, Legrand AC, van Stolk-Cooke K, Acierno R. An examination of social support and PTSD treatment response during prolonged exposure. Psychiatry. 2018;81(3):258–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2017.1402569.

McGuire AP, Gauthier JM, Anderson LM, Hollingsworth DW, Tracy M, Galea S, et al. Social support moderates effects of natural disaster exposure on depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: effects for displaced and nondisplaced residents. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(2):223–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22270.

Garza K, Jovanovic T. Impact of gender on child and adolescent PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(11):87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0830-6.

Kornfield SL, Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. What does sex have to do with it? The role of sex as a biological variable in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(6):39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0907-x.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: BZ, KE, MMJ. Data collection: JG, SCA. Analysis and interpretation: BZ, MMJ, SCA, JCS. Draft manuscript preparation: BZ, KE, SG, SCA, JCS, MMJ. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee on Human Research, Bern, waived the requirement for ethics approval and the need to obtain consent for the collection, analysis, and publication of the data for this study (KEK Req-2020-00739). However, oral informed consent was obtained from the participating next of kin. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Full departmental disclosure: BZ, KE, JG, JCS, and MMJ report grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd., Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestle, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lilly and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien, Hemotune, Phagenesis, Philips Medical, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, and Nycomed outside the submitted work. The money received was paid into departmental funds. No personal financial gain applied. SAC declares that no conflict of interest exists.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Items of the adapted FS-ICU-24R. Table S2. Descriptive analysis of the adapted FS-ICU-24R. Table S3. Item loadings of the adapted FS-ICU-24R. Fig. S1. Scree plot.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zante, B., Erne, K., Grossenbacher, J. et al. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in next of kin during suspension of ICU visits during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry 21, 477 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03468-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03468-9