Abstract

Background

To estimate the prognostic value of inflammatory markers in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC).

Methods

A total of 361 resected LSCC patients were included. The preoperative and postoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and l actate dehydrogenase (LDH) were assessed. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox regression analysis were conducted on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Both Kaplan-Meier analysis and univariate analysis demonstrated significant prognostic value of preoperative and postoperative NLR, PLR and MLR. However, only preoperative ALP was predictive of OS and PFS, and LDH failed to be predictor of OS and PFS. The multivariate analysis showed that preoperative NLR (OS: HR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.06–2.54, p = 0.026; PFS: HR = 1.52, 95%CI: 1.04–2.23, p = 0.029) and postoperative MLR (OS: HR = 2.02, 95%CI: 1.29–3.14, p = 0.002; PFS: HR = 1.57, 95%CI: 1.05–2.34, p = 0.026) were independently related with survival.

Conclusions

The elevated preoperative NLR, PLR, MLR and ALP were significantly associated with worse survival and cancer progression. The preoperative NLR and postoperative MLR might be independent prognostic markers of OS and PFS in LSCC patients undergoing surgical resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laryngeal cancer is one of the most common cancers in head and neck region with 26,300 new cases and 14,500 deaths in China in 2015 [1]. The 5-year overall survival rate was approximately 60% in the United States based on SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) accounts for 85–95% of laryngeal cancer [2]. Various treatments are used to cure laryngeal cancer patients, including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [3]. However, the review of American Cancer Society suggested that 5-year survival rate was on the decline despite the improvement of therapy [4, 5]. Therefore, it is of great importance to estimate the effectiveness of novel prognostic markers for predicting survival and optimizing therapeutic strategies in LSCC patients.

Pathological TNM stage was considered as the best predictor of long-term survival [6], but it is not available before surgery. Recent evidences have proved that tumor-related immune responses are significantly related with tumor progression [7]. Cytokines produced by tumor cells or tumor microenvironment can stimulate the host inflammation, which led to a rise of circulating peripheral blood cells, including neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and monocyte [8]. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was related with tumorigenesis, aggressiveness and poor prognosis [9]. Meanwhile, the platelets can promote the angiogenesis, microvascular permeability and extravasation of tumor cells [10]. Accordingly, the NLR and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have reflected significant prognostic role in different cancers, including prostate cancer and lung cancer [11, 12]. And NLR was regarded as a better predictor than PLR in several studies [13]. The monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were also reported as prognostic factors [14]. In terms of LSCC, high preoperative NLR and PLR were significantly relevant with worse OS and PFS in LSCC patients [10, 15, 16]. However, the independent prognostic value of NLR and PLR based on multivariate analysis still remains controversial. The MLR, LDH and ALP have not been systematically estimated, which need further analysis and discussion.

The aim of this study was to estimate and compare the prognostic value of inflammatory markers (NLR, PLR, MLR, ALP and LDH) on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in LSCC patients treated with surgical resection. Therefore, we performed a retrospective and single-center study with a large sample of 361 eligible patients.

Methods

Patients

A total of 361 patients diagnosed with LSCC in the West China Hospital (Sichuan, China) from January 2010 to December 2014 were included in the present study. Patients were included refers to the following criteria: (1) LSCC was confirmed by pathological examination; (2) patients were older than 18 years old; (3) patients underwent laryngectomy without neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (4) clinical information such as laboratory test and radiologic examination was complete; (5) the minimum follow-up period was 3 years; and (6) patients had no concurrent acute inflammatory diseases or haematological disorders that might affect the level of inflammatory markers.

Data extraction and follow-up

We extracted the data of patient demographics, laboratory tests, imaging reports and pathologic characteristics from electronic medical records. The TNM stage of laryngeal cancer was confirmed by pathological findings primarily and imaging reports secondly according to AJCC- TNM stage seventh edition [17]. The NLR, PLR, MLR, ALP and LDH were obtained from blood tests within 1 week before surgery (preoperative), and 2 week to 1 month after surgery but before adjuvant therapy (postoperative). Patients were evaluated through routine radiologic and laboratory reexamination and telephone follow-up. The median period of follow-up was 47 months (range: 4–98). The endpoints were OS and PFS. The OS was measured from the date of pathologic diagnosis to death, and the PFS referred to the period from pathologic diagnosis to the date of recurrence, metastasis or death. In addition, the living patients without cancer progression were censored on the last follow-up. The patients were followed up until December 2017 or their death.

Statistical analysis

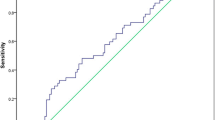

The differences between patients grouped by high and low level of preoperative NLR PLR and MLR were evaluated by Chi squared test. The t-test and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the mean value of preoperative inflammatory markers. After classifying the patients with cancer progression, we calculated the optimal cutoff values of NLR, PLR, MLR, ALP and LDH based on maximum Youden index (sensitivity+specificity− 1) through receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis. Survival curves were obtained by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and compared by log-rank test. Both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate the association between inflammatory markers and survival outcome. The significant variables in univariate analysis or Chi squared test were included in multivariate analysis. The multivariable analysis was conducted through forward stepwise (Likelihood Ratio) selection, thus only the significant variables were present with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We performed all the statistical analyses on SPSS version 21.0 and p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Cutoff values of inflammatory markers

According to the ROC curves, the areas under the curve (AUCs) and 95%CIs of preoperative NLR, PLR, MLR, ALP and LDH were 0.631 (0.569–0.692, P < 0.001), 0.612 (0.543–0.680, P = 0.002), 0.573 (0.514–0.632, P = 0.017), 0.563 (0.495–0.631, P = 0.074) and 0.493 (0.429–0.558, P = 0.841), respectively. The optimal cutoff value was 2.45 for NLR, 114 for PLR, 0.21 for MLR, 78 (U/L) for ALP and 185 (U/L) for LDH. In the same way, the AUCs and 95%CI of postoperative NLR, PLR, MLR, ALP and LDH were 0.568 (0.509–0.627, P = 0.025), 0.605 (0.542–0.688, P = 0.001), 0.614 (0.550–0.678, P < 0.001), 0.495 (0.423–0.568, P = 0.895) and 0.524 (0.460–0.587, P = 0.466), respectively. The optimal cutoff value was 2.85 for NLR, 111 for PLR, 0.36 for MLR, 84 (U/L) for ALP and 158 (U/L) for LDH.

Baseline characteristics of patients

The entire cohort (N = 361) consisted of 353 male and 8 female with median age at diagnosis of 60 years old (range: 35–87). The detailed process of patient selection was presented in Additional file 1: Figure S1. All patients were diagnosed with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma without distant metastases. The postoperative therapies included intensity-modulated radiation therapy and cisplatin based chemotherapy. There were 62 and 6 patients received radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone, and 20 patients underwent both chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Forty-seven patients had medications that might affect inflammatory markers within 1 week before blood test. A total of 87 patients had comorbidities, 51, 20 and 6 patients had hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipemia. In addition, 14, 5 and 3 patients had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease and gastritis.

The grouped clinicopathological parameters according to NLR, PLR and MLR were showed in Table 1. Significant differences were found in the distribution of tumor location and histology between high and low PLR groups. Compared with low NLR/PLR group, there were more patients with worse T classification and TNM stage in the high NLR/PLR group. The NLR, PLR and MLR were all significantly relevant with selection of surgical removal. We also compared the mean value of preoperative inflammatory markers by patient’s clinicopathological characteristics (Additional file 2: Table S1). The adverse tumor features including worse T classification, advanced TNM stage and total laryngectomy were associated with higher level of inflammatory markers.

Overall survival according to preoperative inflammatory markers

On the last follow-up, 40 (17.1%) and 49 (42.5%) patients were died in the NLR < 2.45 and NLR ≥ 2.45 groups, the 5-year OS rates were 81.8% and 60.3% (p < 0.001). The univariate HR and 95% CI of NLR was 2.53 (1.66–3.84, p < 0.001). The survival results were also significantly different between the PLR (HR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.35–3.12, p = 0.001), MLR (HR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.30–3.06, p = 0.002) and ALP (HR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.05–2.41, p = 0.030) groups (Fig. 1, Table 2). However, the LDH failed to show significant prognostic role.

In terms of clinicopathological parameters, the patient’s age (p = 0.009), tumor location (all p < 0.001), T classification (p < 0.001), N classification (p < 0.001), TNM stage (p < 0.001), histology (p < 0.001) and laryngectomy methods (p < 0.001) were found statistically significant in univariate analysis (Table 3). However, the multivariate analysis only supported that NLR (HR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.06–2.54, p = 0.026), tumor location (glottic vs. supraglottic, HR = 2.71, 95%CI: 1.26–5.80, P = 0.011) and TNM stage (HR = 4.24, 95%CI: 2.13–7.79, p < 0.001) were independent prognostic factors of OS in LSCC patients (Table 4).

Progression-free survival according to preoperative inflammatory markers

There were 117 patients had evidence of cancer progression. Forty, 15 and 7 patients developed local recurrence, cervical lymph nodes metastases and distant metastases, respectively. The 5-year PFS rates were 73.8% and 50.9% in two NLR groups (p < 0.001), 69.3% and 57.0% in two PLR groups (p = 0.015). Both high NLR (HR = 2.13, 95%CI: 1.49–3.07, p < 0.001) and PLR (HR = 1.58, 95%CI: 1.09–2.29, p = 0.016) were related with decreased PFS in univariate analysis (Fig. 2, Table 2). The HRs and 95%CIs were 1.61 (1.12–2.32, p = 0.011) of MLR groups and 1.48 (1.03–2.13, p = 0.034) of ALP groups, which reflected additional PFS benefiting from low MLR or ALP (Fig. 2, Table 2). Significant differences of survival curve were not found in the analysis of LDH (p = 0.451).

In univariate analysis, the patient’s age (p = 0.020), tumor location (p = 0.008, p < 0.001), T classification (p < 0.001), N classification (p < 0.001), TNM stage (p < 0.001), histology (p < 0.001) and laryngectomy (p < 0.001) reflected significant predictive values of PFS (Table 3). In the multivariate model, high NLR (HR = 1.52, 95%CI: 1.04–2.23, p = 0.029) and advanced TNM stage (HR = 3.41, 95%CI: 2.25–5.16, p < 0.001) remained independent predictors for poor PFS in LSCC patients (Table 4).

Survival according to postoperative inflammatory markers

In terms of OS, the HRs and 95%CIs were 3.18 (2.08–4.86, p < 0.001), 3.13 (1.98–4.94, p < 0.001), 3.65 (2.40–5.56, p < 0.001) for NLR, PLR and MLR, respectively (Table 2, Additional file 3: Figure S2). The high NLR (HR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.52–3.14, p < 0.001), PLR (HR = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.28–2.68, p = 0.001) and MLR (HR = 2.60, 95%CI: 1.79–3.79, p < 0.001) were associated with worse PFS (Table 2, Additional file 4: Figure S3). Neither ALP nor LDH were significant prognostic factors for OS and PFS. In multivariate analysis, the postoperative MLR was still significantly related with OS (HR = 2.02, 95%CI: 1.29–3.14, p = 0.002) and PFS (HR = 1.57, 95%CI: 1.05–2.34, p = 0.026) (Table 4).

Discussion

Recruited by tumor cells, the tumor infiltrating neutrophils (TINs) can produce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and protease to promote the formation of tumor microenvironment and enhance tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, invasiveness and metastasis [18]. TINs also contribute to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and infiltration growth of tumor cells [19, 20]. Cooperate with tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), TINs can produce IL-6 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, activate the STAT3 signaling pathway to slow down neutrophil degranulation and enhance tumor proliferation [21, 22]. On the contrary, lymphocytes have an adverse effect on growth and maturation of tumor cells [23]. The elevated level of NLR means relative increase of neutrophils and decrease of lymphocytes, thereby increasing the risk of tumor recurrence and metastasis. In previous studies, the preoperative NLR was an independent predictor for OS, cancer-specific survival (CSS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in LSCC according to multivariate analyses [15, 24]. However, studies also indicated non-significant correlation between preoperative NLR and DFS [25], and high NLR was not independently related with poor OS in patients undergoing postoperative radiotherapy [9]. In our study, the preoperative NLR showed significant predictive role of OS and PFS, which supported preoperative NLR was an independent factor in the prognosis of patients with LSCC.

The PLR was also widely used in predicting survival outcome of cancer patients. The tumor cells can increase peripheral platelet count via thrombopoietin, IL-6 or leukemia inhibitory factor [26]. Then platelets can promote the growth and metastasis of tumor cells in turn. For instance, platelets can form platelets-tumor cell complexes to protect tumor cells from immune response. Activated platelets would secrete transforming growth factor-beta to suppress NK cells, and VEGF to promote tumor angiogenesis, which all contribute to the tumor proliferation and metastasis [27, 28]. Therefore, PLR was inversely relevant with patients’ survival and disease progression. The prognostic value of preoperative PLR in LSCC was less reported. The published studies concluded that low PLR was independently associated with better OS, CSS and DFS in multivariate analyses [9, 24]. However, we only found significant predictive role of preoperative PLR in univariate analyses. The PLR failed to be an independent prognostic biomarker, which indicated that preoperative NLR might be a better predictor for OS and PFS in LSCC.

In addition, the prognostic values of MLR, ALP and LDH were also estimated. The high preoperative ALP was prominently related with worse OS and PFS according to this univariate analyses. The increased ALP was often found in bone metastatic tumors or liver lesions, and showed prognostic function in several solid tumors such as metastatic prostate cancer [29]. The higher glycolysis of tumor tissue than normal tissue may result in elevated LDH [30]. However, preoperative LDH had no important effect on OS and PFS in this study. TAMs were derived from circulating monocytes, and the M2 phenotype of TAMs can stimulate tumor-cell proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis via growth factors and angiogenic factors [31]. In our study, preoperative MLR showed prognostic value of OS and PFS in univariate analyses. However, all preoperative MLR, LDH and ALP were not independent predictors of OS and PFS, which urged more studies about MLR, ALP and LDH in LSCC patients.

There were few studies examining the prognostic role of post-treatment inflammatory markers in laryngeal cancer. Previous study indicated that post-treatment neutrophil count was related with OS and local control, but post-treatment NLR didn’t show prognostic value in oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer undergoing radiotherapy [32]. However, the post-treatment NLR was an independent predictor of OS and PFS in advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma receiving chemoradiotherapy [33]. In this study, the high postoperative NLR, PLR and MLR were significantly associated with increased risk of death and tumor progression. And postoperative MLR remained an independent predictor of OS and PFS in LSCC patients.

Among the clinicopathological factors, TNM stage is widely used in estimation of prognosis and selection of standardized treatment plan. The present study also supported TNM stage as an independent prognostic factor of OS and PFS. However, whether age is an effective predictor of survival outcome remains controversial. The age at diagnosis was an independent predictor of OS in several previous articles [16, 34]. In contrast, researchers also found that there was no significant association between age and prognosis [3, 35]. Based on our study, age at diagnosis only had effect on prognosis in univariate analyses. Pathological T classification, N classification, histological differentiation, adjuvant therapy, medication and comorbidities failed to show significant results. Therefore, the independent prognostic value of clinicopathological factors and inflammatory markers requires further investigation.

There were several limitations in the present study. First of all, this study was a retrospective and single-center study that might cause selection bias, thus prospective and multi-center studies were needed to support the prognostic role of inflammatory markers. Secondly, although we added the significant parameters in Chi squared test into multivariate analyses, the various patients’ characteristics could be potential confounders that influence the survival outcome. Furthermore, since our study was limited to Chinese population, the preliminary results may not apply to other ethnic populations.

Conclusions

In summary, elevated preoperative NLR, PLR, MLR and ALP were significantly associated with worse OS and PFS in LSCC patients undergoing surgical resection. In addition, preoperative NLR and postoperative MLR might be independent prognostic biomarkers for identifying survival outcome and cancer progression. The inflammatory markers were suggested to be novel and effective predictors with simple examination method. However, it still needs to be proved by further multi-center and large-scale prospective studies.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

alkaline phosphatase

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- CI:

-

confidence intervals

- CSS:

-

cancer-specific survival

- DFS:

-

disease-free survival

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- LSCC:

-

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- MLR:

-

monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NLR:

-

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PFS:

-

progression-free survival

- PLR:

-

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ROC:

-

receiver operating curve

- TAM:

-

tumor-associated macrophages

- TINs:

-

tumor infiltrating neutrophils

References

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32.

Schorn VJ, Miles BA. Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. New York: Springer; 2014.

Santos TS, Estevao R, Antunes L, Certal V, Silva JC, Monteiro E. Clinical and histopathological prognostic factors in locoregional advanced laryngeal cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(10):948–53.

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29.

Hoffman HT, Porter K, Karnell LH, et al. Laryngeal cancer in the United States: changes in demographics, patterns of care, and survival. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(9 Pt 2 Suppl 111):1–13.

Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American joint committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3622–34.

Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and Cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–99.

Valero C, Pardo L, Lopez M, Garcia J. Pretreatment count of peripheral neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes as independent prognostic factor in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39(2):219–26.

Wang J, Wang S, Song X, et al. The prognostic value of systemic and local inflammation in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:7177–85.

Kara M, Uysal S, Altinisik U, Cevizci S, Guclu O, Derekoy FS. The pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and red cell distribution width predict prognosis in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(1):535–42.

Lorente D, Mateo J, Templeton AJ, et al. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second-line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):750–5.

Dilek U, Celalettin E, Neslihan K, et al. Are neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelet/lymphocyte rates in patients with non-small cell lung cancer associated with treatment response and prognosis? Asian Pac J Cancer P. 2013;14(9):5237–42.

Choi WJ, Cleghorn MC, Jiang H, Jackson TD, Okrainec A, Quereshy FA. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a better prognostic serum biomarker than platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients undergoing resection for nonmetastatic colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S603–13.

Kano S, Homma A, Hatakeyama H, et al. Pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as an independent prognostic factor for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;39(2):247.

Tu XP, Qiu QH, Chen LS, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic marker in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC cancer. 2015;15:743.

Fu Y, Liu W, OuYang D, Yang A, Zhang Q. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts long-term survival in patients undergoing Total laryngectomy with advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center retrospective study. Medicine. 2016;95(6):e2689.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American joint committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–4.

Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Mestas J, Gomperts B, Keane MP, Belperio JA. Cancer CXC chemokine networks and tumour angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(6):768–78.

Grosse-Steffen T, Giese T, Giese N, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and pancreatic tumor cell lines: the role of neutrophils and neutrophil-derived elastase. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:720768.

Gaida MM, Steffen TG, Gunther F, et al. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils promote dyshesion of tumor cells and elastase-mediated degradation of E-cadherin in pancreatic tumors. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(12):3369–80.

Galdiero MR, Bonavita E, Barajon I, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Jaillon S. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2013;218(11):1402–10.

Yan B, Wei JJ, Yuan Y, et al. IL-6 cooperates with G-CSF to induce protumor function of neutrophils in bone marrow by enhancing STAT3 activation. J Immunol. 2013;190(11):5882–93.

Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21(2):137–48.

Hsueh C, Tao L, Zhang M, et al. The prognostic value of preoperative neutrophils, platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes and calculated ratios in patients with laryngeal squamous cell cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(36):60514–27.

Wong BY, Stafford ND, Green VL, Greenman J. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1903–8.

Ciurea SO, Hoffman R. Cytokines for the treatment of thrombocytopenia. Semin Hematol. 2007;44(3):166–82.

Gersuk GM, Westermark B, Mohabeer AJ, Challita PM, Pattamakom S, Pattengale PK. Inhibition of human natural killer cell activity by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). III. Membrane binding studies and differential biological effect of recombinant PDGF isoforms. Scand J Immunol. 1991;33(5):521–32.

Varon D, Shai E. Role of platelet-derived microparticles in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Discov Med. 2009;8(43):237–41.

Brasso K, Christensen IJ, Johansen JS, et al. Prognostic value of PINP, bone alkaline phosphatase, CTX-I, and YKL-40 in patients with metastatic prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 2006;66(5):503–13.

Fantin VR, Stpierre J, Leder P. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(6):425.

Sica A, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cancer related inflammation: the macrophage connection. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):204–15.

Sumner WA, Stokes WA, Oweida A, et al. Survival impact of pre-treatment neutrophils on oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy.[J]. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):168.

Kim DY, Kim IS, Park SG, et al. Prognostic value of posttreatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated by chemoradiotherapy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2017;44(2):199–204.

Ramroth H, Schoeps A, Rudolph E, et al. Factors predicting survival after diagnosis of laryngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(12):1154–8.

Nguyen TD, Malissard L, Theobald S, et al. Advanced carcinoma of the larynx: results of surgery and radiotherapy without induction chemotherapy (1980-1985): a multivariate analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36(5):1013–8.

Funding

The authors declare no funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC collected, analyzed the data and wrote the article. XM designed the study. HZ and JY analyzed the data. YL, DZ and JW contributed to the data of medical records. CK, SZ and MW contributed to the data of follow-up. All authors revised and approved the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institution Ethics Commission of West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The need for consent to participate was waived by Ethics Commission of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The flowchart of patient selection. (TIF 4156 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. The mean value of preoperative inflammatory markers by patient’s clinicopathological characteristics (DOCX 27 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for postoperative NLR (A), PLR (B), MLR (C), ALP (D) on overall survival. (TIF 4684 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S3. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for postoperative NLR (A), PLR (B), MLR (C), ALP (D) on progression-free survival. (TIF 4684 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Zeng, H., Yang, J. et al. Survival and prognostic analysis of preoperative inflammatory markers in patients undergoing surgical resection for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 18, 816 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4730-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4730-x