Abstract

Background

Somatic amplifications of the LYL1 gene are relatively common occurrences in patients who develop uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC) as opposed to other cancers. This study was undertaken to determine whether such genetic alterations affect survival outcomes of UCEC.

Methods

In 370 patients with UCEC, we analysed clinicopathologic characteristics and corresponding genomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas database. Patients were stratified according to LYL1 gene status, grouped as amplification or non-amplification. Heightened levels of cancer-related genes expressed in concert with LYL1 amplification were similarly investigated through differentially expressed gene and gene set enrichment analyses. Factors associated with survival outcomes were also identified.

Results

Somatic LYL1 gene amplification was observed in 22 patients (5.9%) with UCEC. Patients displaying amplification (vs. non-amplification) were significantly older at the time of diagnosis and more often were marked by non-endometrioid, high-grade, or advanced disease. In survival analysis, the amplification subset showed poorer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates (3-year PFS: 34.4% vs. 79.9%, P = 0.031; 5-year OS: 25.1% vs. 84.9%, P = 0.014). However, multivariate analyses adjusted for tumor histologic type, grade, and stage did not confirm LYL1 gene amplification as an independent prognostic factor for either PFS or OS. Nevertheless, MAPK, WNT, and cell cycle pathways were significantly enriched by LYL1 gene amplification (P < 0.001, P = 0.002, and P = 0.004, respectively).

Conclusions

Despite not being identified as an independent prognostic factor in UCEC, LYL1 gene amplification is associated with other poor prognostic factors and correlated with upregulation of cancer-related pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Uterine corpus endometrial cancer (UCEC) imposes a global burden in both developed and developing countries [1]. In the United States, it is the most common gynecologic malignancy, accounting for 61,380 new cases in 2017 [2]. In Korea, the incidence of UCEC is clearly increasing and is estimated to comprise 2.5% (2578) of all new female cancers in 2017 [3, 4].

In 2013, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network issued an integrated report of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiles in 373 patients diagnosed with UCEC [5]. Furthermore, this consortium determined four prognostic categories (good→poor as shown) for classification of UCEC: (1) polymerase ɛ (POLE) ultramutated; (2) microsatellite instability (MSI) hypermutated; (3) low copy number; and (4) high copy number. The high copy number group in particular includes most of the serous and serous-like endometrioid tumors, sharing genomic features with ovarian serous carcinomas. Researchers have since incorporated these molecular criteria into clinical trials designed to gauge postsurgical adjuvant treatment of UCEC (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN11659025).

In keeping with the era of precision medicine, discovery of reliable genetic changes is essential to provide individualized treatment of patients with UCEC [5, 6]. Little-known genes such as LYL1 may now be identified as novel prognostic indicators or as potential therapeutic targets. The LYL1 gene is located on the short (p) arm of chromosome 19 at position 13.13, where it encodes a protein implicated in blood vessel maturation and haematopoiesis [7]. As a member of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family, the LYL1 gene is also known to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation [8], and a form of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia has been linked to a chromosomal aberration of LYL1 [7].

Curiously, somatic amplifications of the LYL1 gene frequently accompany UCEC, more so than most other cancers, ranking second among TCGA listings. However, its ramifications in this setting have yet to be fully explored. The current study, entailing TCGA database analysis, was undertaken to determine whether genetic alterations in the LYL1 gene (such as amplification) may impact survival outcomes in patients with UCEC.

Methods

Data acquisition

We downloaded genomic alteration data on patients with UCEC and corresponding clinicopathologic profiles at the Genomics Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org) web portals. The Illumina Genome Analyzer served as platform for DNA sequencing (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). This study complied with TCGA publication guidelines and policies (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/publications/publicationguidelines). The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital ruled that no formal ethics approval was required in this study.

Study population

In total, 370 patients with UCEC qualified for this study. The clinicopathologic data collected included age, underlying comorbidities, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, tumor histologic type and grade, and treatment of UCEC (ie, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy). Tumor MSI status was also collected. Patients were assigned to LYL1 gene amplification and non-amplification groups as warranted.

Bioinformatics analysis

LYL1 gene status, especially whether it was amplified, was determined through the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org). Level-3 data of patients with UCEC and raw reads (HTSeq-counts) of differentially expressed gene (DEG) analyses were accessed via FireBrowse (http://firebrowse.org). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of gene expression data [9] was subjected to Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [10]. For visualization of enrichment pathway, the NetworkAnalyst (http://www.networkanalyst.ca) was used [11].

In doing so, the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database was applied, achieving confidence scores of 400–1000 [12]. DEGs were identified through open-source software analysis (R package DESeq2; http://www.bioconductor.org) [13].

Statistical analysis

To compare clinicopathologic features of the two patient subsets, Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U-test were applied to continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

We defined PFS as the time elapsed between date of initial diagnosis and date of disease progression, whereas overall survival (OS) represented the time interval between date of initial diagnosis and date of cancer-related death or end of study. Survival estimates were generated via Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were engaged to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For survival analytics, we relied on commercially available software (SPSS v21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Open-source programming (R v2.12.1, ISBN 3–900,051–07-0, http://www.R-project.org; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for all other computations. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

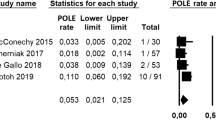

Somatic copy number variations in UCEC

Frequencies of somatic amplifications involving the LYL1 gene are depicted according to TCGA classification in Fig. 1a. UCEC ranked second among cancers in terms of LYL1 gene amplification. In genomic alteration analyses, chromosomes 1q, 3q, 8q, 17q, and 19p were frequently amplified in this patient population (Fig. 1b). The LYL1 gene of 19p arm was amplified in 5.9% (22/370) of patients with UCEC. Additionally, the LYL1 gene was one of the 15 mostly amplified oncogenes filtered by gene family in GSEA (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, the 15 mostly deleted tumor suppressor genes, including PTEN, are displayed in Fig. 1d.

Analysis of gene amplification in various cancer types and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma: a frequencies of copy number variations across chromosomes; b frequencies of LYL1 gene amplification in various cancer types; c correlations between amplification frequencies and mortality across top 15 oncogenes; and (d) correlations between deletion frequencies and mortality across top 15 tumor suppressor genes in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

Characteristics of patients with UCEC

Patients’ clinicopathologic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean patient age was 63 years. Of the 370 patient participants, 304 (82.2%), 52 (14.1%), and 14 (3.8%) displayed endometrioid, serous, and mixed histologic types of UCEC, respectively. Members of the LYL1 amplification (vs. non-amplification) group were significantly older at time of diagnosis and more often exhibited biologically aggressive tumors, marked by advanced-stage disease (FIGO stage III-IV; P = 0.003), high-grade malignancy (grade 3; P < 0.001), and serous histologic type (P < 0.001). Proportions of the four TCGA categories of UCEC also showed comparative differences, with 72.7% of amplification group members achieving high copy number rank, versus 12.1% in the non-amplification group (P < 0.001). In terms of adjuvant treatment, chemotherapy recipients were more numerous in LYL1 amplification group than in non-amplification group (50.0% vs 28.4%; P = 0.032) (Table 1).

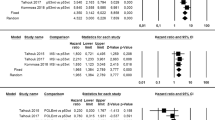

Between-group comparisons of survival outcomes and identification of prognostic factors

During the observation period (median, 23.9 months; range, 0.5–191.7 months), 5 patients in the amplification group and 34 in the non-amplification group died of their disease. Survival analysis indicated poorer 3-year PFS (34.4% vs. 79.9%; P = 0.031) and 5-year OS (25.1% vs. 84.9%; P = 0.014) in the amplification (vs. non-amplification) group (Fig. 2).

LYL1 gene amplification also showed a significant association with poor OS in univariate analysis (P = 0.019) (Table 2). However, after adjusting for variables such as histologic type, grade, and FIGO stage, LYL1 gene status was not confirmed as a significant prognostic factor in OS. Only advanced-stage disease (FIGO stage III-IV) emerged as an independent predictor of poor prognosis (adjusted HR, 3.509; 95% CI, 1.734–7.101; P < 0.001). Table 2 also presents factors associated with PFS. In univariate analysis, LYL1 gene amplification was associated with poor PFS (P = 0.037), but its statistical significance was not sustained in multivariate analysis. Advanced-stage disease (FIGO stage III-IV) was identified as an independent poor prognostic factor for PFS (adjusted HR, 3.581; 95% CI, 1.981–6.473; P < 0.001).

We also stratified patients by tumor histologic type for subgroup analysis. In those with endometrioid cancers (n = 304), neither PFS (P = 0.070) nor OS (P = 0.323) differed significantly by LYL1 gene status (amplification vs. non-amplification). However, results of multivariate analysis showed a trend towards worse PFS in the patients with LYL1 gene amplification (adjusted HR, 4.093; 95% CI, 0.926–18.012; P = 0.063) (Table 3).

DEGs in LYL1 amplified tumors

We performed GSEA pathway analysis of 993 genes showing increased levels of expression in conjunction with LYL1 amplification. Consequently, we found significant upregulation of MAPK (P < 0.001), WNT (P = 0.002), cell cycle (P = 0.004), and cancer-related (P < 0.001) pathways (Fig. 3a, b). Of 993 DEGs, 384 cancer-related genes filtered via STRING database were enriched through these pathways. MYC, CDK6, PRKACA, and ERBB2 genes were found to frequently interact with other cancer-related genes (Fig. 3c).

Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), shown by LYL1 gene status: a significantly enriched pathway analysis in upregulated 993 DEGs; b expression levels of enriched DEGs across LYL1 amplification; and (c) genes in significant gene networks bearing simplified KEGG pathway annotations and grouped process-wise by commonest term prevailing in network (node size defined by degree of interaction)

We also conducted GSEA according to histologic types and TCGA classes (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Among the four TCGA classes, only the high copy number group showed LYL1 amplifications, and cell proliferation pathway was significantly enriched in this group. Compared to endometrioid type, cancer-related and cell proliferation pathways and genes were more commonly enriched in serous type (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Discussion

In the present study, we used TCGA database analysis to determine the potential impact of LYL1 gene amplification on survival outcomes in patients with UCEC. Although patients displaying LYL1 gene amplification showed poorer PFS and OS compared to those with non-amplification, multi-variate analyses failed to prove it as an independent prognostic factor.

A number of studies have been similarly conducted to date to identify novel biomarkers for patient survival in various types of cancer. In particular, the prognostic impact made by altered expression levels of L1CAM and MYC, both homeobox gene family members, has been researched through TCGA database analysis [14,15,16]. The LYL1 gene, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and a known oncogene in human and mouse cancers, is linked to many cancer-related properties, such as angiogenesis [17,18,19]. Through genetic and epigenetic modulations, the LYL1 gene acts to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation [8]. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have also demonstrated its interactions with various oncogenes, such as MYC, TAL1, TAL2, and LMO2 [20, 21].

Through our TCGA data analysis of LYL1 gene amplification in patients with UCEC, we discovered that overexpressed cancer-related genes are enriched by MAPK, WNT, and cell cycle pathways in such patients. Specifically, MYC, CDK6, PRKACA, and ERBB2, all well-known oncogenes and cancer markers, were overexpressed in conjunction with LYL1 gene amplification. Both MYC and ERBB2 have likewise shown associations with uterine cancers in earlier studies [22,23,24,25,26]. Additionally, expression of PRKACA was positively correlated with LYL1 amplification (Pearson’s coefficient (r), 0.442).

Unfortunately, only advanced-stage disease emerged as a significant marker of poor prognosis in multivariate analyses. LYL1 gene amplification was not identified as an independent prognostic factor. However, most of our cohort had early-stage disease (FIGO stages I and II: 68.6% and 6.5%, respectively). According to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data of the National Cancer Institute, the 5-year survival rate for UCEC with distant metastasis is a dismal 16.2%, compared with 95.3% for disease confined to primary sites [27]. It is thus apparent that the stage of UCEC impacts survival outcomes dramatically, hindering analysis of amplification effects in the current study population.

The current study has several acknowledged limitations, the first being that associations between the LYL1 gene and other genes or genetic mechanisms were not validated, and the proteins expressed were not measured. Such proteogenomic studies would perhaps underscore the effects of these genetic alterations and the accuracy and completeness of genomic profiling. In addition, further efforts to identify the genetic and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of the LYL1 gene and an evaluation of its efficacy as a prognostic indicator and therapeutic target are warranted. In UCEC cell lines, the LYL1 gene could be overexpressed or inhibited by siRNA, determining subsequent flux in cell differentiation, proliferation, or death. A LYL1 gene knock-out patient-derived xenograft animal model is one possible investigative approach. Another limitation was the sample size of the LYL1 gene amplification group (n = 22), which was too small for reasonable statistical inferences. Despite these drawbacks, we were able to explore the prognostic potential of the novel LYL1 gene in the setting of UCEC using both TCGA and clinicopathologic data. LYL1 gene amplification and its association with expression levels of other genes were demonstrated as well.

Conclusions

In conclusion, LYL1 gene amplification is not identified as an independent prognostic factor in UCEC. However, we discovered that cancer-related pathways, such as MAPK, WNT, and cell cycle pathways are upregulated in patients with LYL1 amplification. Correlations between LYL1 amplification and increased expression levels of cancer-related genes (MYC, CDK6, PRKACA, and ERBB2) are also observed. Its potential for prognostic indicator and therapeutic targeting may be implied based on overexpression of such affiliated oncogenes. Additional multi-omics and genome-wide data studies are warranted.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- KEGG:

-

The kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

FIGO

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- POLE:

-

Polymerase ɛ

- STRING:

-

The search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins

- TCGA:

-

The cancer genome atlas

- UCEC:

-

Uterine corpus endometrial cancer

References

Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, et al. The global burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505–27.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30.

Lim MC, Moon EK, Shin A, Jung KW, Won YJ, Seo SS, et al. Incidence of cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in Korea, 1999-2010. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013;24:298–302.

Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH. Prediction of Cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2017. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:306–12.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73.

Hodson R. Precision medicine. Nature. 2016;537:S49.

LYL1 [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004 – [cited 2018 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/4066/.

San-Marina S, Han Y, Suarez Saiz F, Trus MR, Minden MD. Lyl1 interacts with CREB1 and alters expression of CREB1 target genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:503–17.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–61.

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50.

Xia J, Gill EE, Hancock RE. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:823–44.

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–52.

Varet H, Brillet-Gueguen L, Coppee JY, Dillies MA. SARTools: a DESeq2- and EdgeR-based R pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-Seq data. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157022.

Dellinger TH, Smith DD, Ouyang C, Warden CD, Williams JC, Han ES. L1CAM is an independent predictor of poor survival in endometrial cancer - an analysis of the Cancer genome atlas (TCGA). Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:336–40.

Eoh KJ, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Nam EJ, Kim S, Kim SW, et al. Upregulation of homeobox gene is correlated with poor survival outcomes in cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:84396–402.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15.

Meng YS, Khoury H, Dick JE, Minden MD. Oncogenic potential of the transcription factor LYL1 in acute myeloblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1941–7.

Pirot N, Deleuze V, El-Hajj R, Dohet C, Sablitzky F, Couttet P, et al. LYL1 activity is required for the maturation of newly formed blood vessels in adulthood. Blood. 2010;115:5270–9.

Orsulic S, Li Y, Soslow RA, Vitale-Cross LA, Gutkind JS, Varmus HE. Induction of ovarian cancer by defined multiple genetic changes in a mouse model system. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:53–62.

Bain G, Engel I, Robanus Maandag EC, te Riele HP, Voland JR, Sharp LL, et al. E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in alphabeta T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4782–91.

Deleuze V, El-Hajj R, Chalhoub E, Dohet C, Pinet V, Couttet P, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is a direct transcriptional target of TAL1, LYL1 and LMO2 in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40484.

Li L, Osdal T, Ho Y, Chun S, McDonald T, Agarwal P, et al. SIRT1 activation by a c-MYC oncogenic network promotes the maintenance and drug resistance of human FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:431–46.

Tadesse S, Yu M, Kumarasiri M, Le BT, Wang S. Targeting CDK6 in cancer: state of the art and new insights. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(20):3220–30.

Martinez-Ledesma E, Verhaak RG, Trevino V. Identification of a multi-cancer gene expression biomarker for cancer clinical outcomes using a network-based algorithm. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11966.

Elsahwi KS, Santin AD. erbB2 overexpression in uterine serous Cancer: a molecular target for Trastuzumab therapy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/128295.

Subramaniam KS, Omar IS, Kwong SC, Mohamed Z, Woo YL, Mat Adenan NA, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote endometrial cancer growth via activation of interleukin-6/STAT-3/c-Myc pathway. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:200–13.

National Cancer Institute. SEER Research Data 1973–2014 [Internet]. Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch; 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.seer.cancer.gov/.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study were downloaded at the Genomics Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org) web portals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML, YSS, and JSS contributed to the study conception and design. SIK, JWL, and NL analysed and interpreted the data. SIK, JWL, and ML were major contributors in writing the manuscript. HSK, HHC, JWK, and NHP involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it. All authors have read and approved the original and revised versions of the manuscript, as well as the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complied with TCGA publication guidelines and policies (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/publications/publicationguidelines). A local ethics committee, the Seoul National University Hospital Institutional Review Board, ruled that no formal ethics approval was required in this particular case.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Gene set enrichment analysis according to histologic types and TCGA classes. (PNG 144 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Enriched genes of cancer-related and cell proliferation pathways according to the two histologic types; serous and endometrioid. (PNG 486 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.I., Lee, J.W., Lee, N. et al. LYL1 gene amplification predicts poor survival of patients with uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma: analysis of the Cancer genome atlas data. BMC Cancer 18, 494 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4429-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4429-z