Abstract

Background

Anxiety and depression can be a long-term strain in cancer survivors. Little is known about the emotional situation of cancer survivors who have to deal with work- and family-related issues. The purpose of this study was to investigate anxiety and depression in working-age cancer survivors and associated factors.

Methods

A register-based sample of 3370 cancer survivors (25 to 55 years at time of diagnosis) diagnosed up to six years prior to the survey was recruited from two German cancer registries. Demographic and medical characteristics as well as self-reported measures were used.

Results

Overall, approximately 40% of the survivors reported moderate to high anxiety scores and approximately 20% reported moderate to high depression scores. Compared to the general population, working-age cancer survivors were more anxious but less depressed (p < .001). Subgroups with regard to time since diagnosis did not differ in anxiety or depression. Anxiety and depression in cancer survivors were associated with various variables. Better social support, family functioning and physical health were associated with lower anxiety and depression.

Conclusions

Overall, we found higher anxiety levels in cancer survivors of working-age than in the general population. A considerable portion of cancer survivors reported moderate to high levels of anxiety and depression. The results indicate the need for psychosocial screening and psycho-oncological support e.g. in survivorship programs for working-age cancer survivors. Assessing the physical health, social support and family background might help to identify survivors at risk for higher emotional distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer patients display higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to the general population [1]. In particular, newly diagnosed cancer patients and patients under treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiation, are emotionally distressed [2,3,4].

The increase of the 5-years survival rate during the last decades contributes to a higher rate of cancer patients becoming long-term survivors and dealing with side effects of treatment and diagnosis [5]. Additionally to physical consequences, some studies suggest increased levels of anxiety and depression even years after diagnosis [6, 7]. Other studies report low levels of depression and anxiety [8, 9]. So far, in most studies on anxiety and depression the mean age of participants was 55 years or older [2,3,4, 7, 10]. Studies with younger cancer survivors have mainly focused on breast cancer patients [6, 8, 9, 11] or testicular cancer patients [12, 13].

According to Erikson’s theory of adult development, central developmental tasks during the developmental stages from 20 to 64 years (intimacy vs. isolation, generativity vs. stagnation) are forming a close relationship, raising children or building an economic existence e.g. with regard to work [14]. A cancer disease during this period can lead to particular challenges for patients. Parenting children but also financial aspects and career changes may lead to a high pressure to get well [15, 16]. Navigating family life during the trajectory of the cancer disease demands a careful balance between the roles as patient and parent [15]. At the same time, cancer disease and treatment can affect the working ability and the reintegration into daily work after successful treatment [17].

Findings of previous studies indicate that younger cancer survivors show higher distress levels than older cancer survivors [1, 9, 11, 18]. Since cancer survivors at working-age face developmental tasks with high responsibilities such as building and caring for a family and establishing the own identity in the social and work environment [14, 19], there is a need to better understand their emotional situation. Identifying the emotional burden and characteristics of cancer survivors most at risk may allow tailored support in after care and survivorship programs to improve their situation.

The first aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in a population-based sample of cancer survivors at working-age (25 to 55 years at the time of diagnosis) and to identify the rate of survivors with clinically relevant psychological burden during cancer survivorship. Secondly, we wanted to compare anxiety and depression in younger survivors to age- and gender-adapted normative values. Finally, we investigated socio-demographic, disease-related and family-related factors associated with anxiety and depression in cancer survivors.

Methods

Study design and participants

In cooperation with two regional cancer registries in northern Germany (Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein), cancer survivors between 25 and 55 years at the time of diagnosis who were diagnosed less than six years prior to the survey were identified as potentially eligible. An information letter, a set of self-report questionnaires, a consent form and a stamped return envelope were sent to all patients. After 4 weeks, non-responders received a reminder letter.

Due to ethical considerations, patients diagnosed with cancer entities with high mortality rates (digestive organs; lower respiratory organs; eye/brain/central nervous system; secondary/ill-defined and other malignant skin neoplasms) were excluded.

Datasets provided by the cancer registries contained date of birth, cancer diagnosis and date of cancer diagnosis for all patients. UICC–staging (TNM classification) was provided for 70.2% of the patients.

The local research ethics committees approved the survey.

Measures

We assessed socio-economic status (SES) using the Winkler-Stolzenberg index [20] including self-reported information on education and occupational qualification, job-related position and family income. The index was categorized into three levels (low, middle and high).

To assess anxiety and depression, the German Version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) was used [21]. Each of the 14 items was rated from 0 to 3, and item scores were generated for the two subscales. Based on the commonly used cut-off scores, patients were assigned to the categories normal (0–7), moderate (8–10) and high (11 or above) levels of anxiety and depression [22]. The instrument shows good to very good validity and satisfactory reliability for both subscales [23].

The Oslo Social Support Scale was used to assess social support [24]. Three questions were asked: ‘How easy is it for you to get practical help from neighbours if you should need it?’ (very easy, easy, possible, difficult, very difficult), ‘How many people are so close to you that you can count on them if you have serious problems?’ (none, 1–2, 3–5, 6 or more) and ‘How much concern do people show in what you are doing?’ (a lot, some, uncertain, little, no concern). The total score was calculated by summarizing the raw scores of each item. Higher scores indicate higher social support. In our sample the internal consistency was 0.71.

Physical quality of life was measured with the physical component summary of the SF-8 Health Survey [25]. The instrument has proven to be reliable and valid [26]. The scale ranges from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate higher physical health.

The general functioning scale of the Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF) [27] was used to measure family functioning. The general functioning scale measures the overall health and pathology of the family with regard to family functioning and shows excellent psychometric properties [27, 28]. Twelve items (6 positive and 6 negative) were rated from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree), and a global family functioning score was generated with higher scores indicating worse family functioning.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Predictive Analytics Software PASW 18.0. To investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer survivors, we used descriptive analyses. To identify the rate of cancer survivors with clinical relevant anxiety and depression during survivorship, we used cut-off scores of the HADS [22, 29]. We conducted group comparisons between cancer survivors with regard to time since diagnosis (<2 years, 3–4 years, 5–6 years >6 years since diagnosis) using chi2-tests for categorical data.

We compared our sample with a representative sample of the German population (N = 4110, mean age 50.3 years) [29] using one-sample t-tests with age- and gender-adapted mean values. For this, we assigned an age- and gender-adapted norm value for each patient, computed the mean value and included it as the reference value.

To investigate the representativeness of the sample, responders and non-responders were compared using chi2-tests for categorical data and t-tests for metric data.

To identify factors associated with anxiety and depression, multiple linear regression analyses utilizing a stepwise backward method with anxiety and depression scores (HADS) as dependent variables were performed. The independent variables entered in the analyses were socio-demographic variables (age at time of the survey (in years), gender (male/female), employment status (employed/unemployed), socioeconomic status (high/middle/low), social support (OSLO)). Family-related variables entered in the analyses were living with a partner (yes/no), having a child aged ≤21 years at the time of diagnosis (yes/no) and family functioning (FAD-GF). Disease-related variables included were number of treatment modalities received (none/one/two/three), cancer diagnosis (breast/female genital organs/male genital organs/hematological/skin/other), time since diagnosis (in months) and physical health (SF-8). Nominal variables were converted into dummy variables.

To estimate effect sizes we used Cohen’s d and Cramer’s V [30]. Two-tailed significance was determined using a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Participants

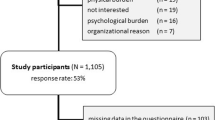

Eight thousand one hundred forty-four patients were invited to participate in the study. Four thousand seven hundred seventy-four persons did not take part in the survey for several reasons (Fig. 1). Altogether, the data from N = 3370 (response rate 41.3%) cancer survivors were included in the analyses (Fig. 1).

Seventy-four percent of the survivors were female; mean age was 50 years (SD 6.8). Most survivors were living with a partner (76%) and were employed in full- or part-time (72%). About half of the survivors had been diagnosed with breast cancer (52%). The mean time since diagnosis was 44 months. We found significant differences between men and women with small effect sizes for most variables. However, men were more likely to be employed in full-time (p < .001, V = 0.45) and belonged more often to upper socioeconomic class (p < .001, V = 0.16). With regard to disease-related variables men and women differed in cancer entities (p < .001, V = 0.79), UICC-stage (p < .001, V = 0.40) and kind of treatment received (p < .001, V = 0.18–0.33) (Table 1).

According to the large sample size, we found statistically significant differences between responders and non-responders in age (mean: 50.1 years vs 49.1 years), gender (74% women vs 66% women), diagnosis (breast cancer 52%vs 38%) and time since diagnosis (mean: 44.4 months vs 46.6 months). However, the effect sizes were small (range d = 0.11 to d = 0.15) [31].

Prevalence of anxiety and depression

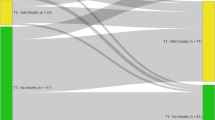

The mean anxiety score of the sample was 6.8 (SD = 4.1) and the mean depression score was 4.1 (SD = 4.0). In the total sample 39% of the survivors reported moderate to high anxiety scores indicating borderline or clinically relevant levels of anxiety. Nineteen percent reported moderate to high depression scores indicating borderline or clinically relevant levels of depression. In the subgroups with regard to time since diagnosis, the rate of survivors with borderline or clinically relevant anxiety scores ranged from 36 to 41%. The rate for borderline and clinically relevant anxiety scores ranged from 17 to 19%. We found no differences in any of the subscales (anxiety, depression) between survivors ≤2 years post diagnosis, survivors 3–4 years post diagnosis, survivors 5–6 years post diagnosis and survivors more than 6 years post diagnosis (Fig. 2).

Anxiety and depression a, months post-diagnosis, n = 3370.

a According to the Cut-Off Scores of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [22]

In the total sample as well as in all subgroups with regard to time since diagnosis, cancer survivors reported statistically significant higher levels of anxiety and lower levels of depression compared with population-based norms (p = .001) (Table 2).

Factors associated with anxiety and depression

Stepwise-backward multiple linear regression analysis revealed that higher anxiety was statistically significant associated with female gender, younger age, less social support, diagnosis breast cancer compared to diagnosis skin cancer, lower physical health and poorer family functioning (Table 3). Being unemployed, receiving less social support, receiving no treatment, shorter time since diagnosis, lower physical health and poorer family functioning were statistically significant associated with higher depression (Table 3). Diagnoses of female or male genital organ cancer, diagnosis of hematological cancer or of the category “other cancer entity” were statistically significant associated with higher depression scores compared to survivors with breast cancer.

The model for depression (adjusted R2 = 45%) performed better than that for anxiety (adjusted R2 = 28%).

Discussion

In this study, we examined anxiety and depression in a large epidemiological sample of cancer survivors of working-age. The findings of this study show that among working-age cancer survivors, about 40% reported elevated levels of anxiety and 20% elevated levels of depression. Anxiety and depression rates of survivors diagnosed 1–2 years or 3–4 years prior to the survey did not differ statistically significant from those of patients diagnosed 5–6 years prior to the survey. These findings are similar to another cross-sectional population-based study in breast cancer survivors (mean age 62 years), who also found no differences in anxiety and depression with regard to time since diagnosis [11]. However, to investigate the course and possible stability of anxiety and depression after diagnosis longitudinal studies on cancer survivors at working-age are necessary.

Depression scores in our sample were statistically significantly lower and anxiety scores were significantly higher than in the general population. Effects between groups for both subscales were small. Nevertheless, the results indicate that cancer diagnosis seems to be a long-term strain regarding anxiety in cancer survivors of working-age. This finding is in line with the conclusions of a meta-analysis in long-term cancer survivors by Mitchell and colleagues (2013) [32]. Cancer survivors may fear cancer recurrence and cancer progress, which may be a stressor even years after diagnosis [33]. Cancer survivors need to adapt to the uncertainty of the cancer disease, which may affect work life and family life [34] and can enhance anxiety. To fulfill their developmental tasks [14], cancer survivors of working-age struggle to stay in workforce, raise their children and get back to ‘normal’ life, which may lead to additional burden. At the same time, better appreciation of life, closer relationships and priority changes may help cancer survivors to overcome depressive symptoms [35].

Several demographic and disease-related variables were significantly associated with anxiety and depression (Table 3). Besides disease-related factors such as cancer entity or number of treatment modalities received, unemployment was statistically significant associated with higher depression scores. Reintegration in daily work and structured daily routines may improve the well-being of cancer patients after treatment [36, 37]. However, in our study the predictive value of employment was statistically significant but rather low. We found no associations between family-related factors such as having minor children or living with a partner and anxiety or depression. It seems that rather psychosocial factors are related to anxiety and depression. Higher social support, better physical functioning and better family functioning were the strongest predictors of lower anxiety and lower depression scores. Better physical health may help to encounter daily requirements successful and hence, rebuild daily life, structure and normalcy after diagnosis and treatment [38]. Furthermore, the results reveal the importance of familial and social background to overcome the burden of cancer disease, and illustrate the importance of supporting all family members to enhance family functioning.

There are some limitations in the current study. Because we used register-based recruitment, all patients were contacted without previous reference to our institution. Nevertheless, a response-rate of 41% was reached, which is similar to other register-based studies [39, 40]. Comparing responders and non-responders, in our sample women and breast cancer survivors are slightly overrepresented and responders are marginally older than non-responders, which may lead to limitations with regard to representativeness of our sample and generalizability of the findings. However, effect sizes of the differences were small. Moreover, UICC staging was only provided for approximately 70% of the patients, and therefore, it was not included in the regression analyses.

Due to ethical reasons, we did not include cancer patients with diagnoses with a high mortality rate in our survey. To prevent families from an additional burden where a patient might have recently died or is in the palliative stage, we excluded tumor diagnoses with poor 5-year-survival rates such as lung cancer and brain tumors. Previous studies assessing anxiety and depression with the HADS found that lung cancer patients and advanced cancer patients reported higher rates of depression than in our sample [2, 41,42,43,44]. Therefore, our study might underestimate anxiety and depression in working-age cancer survivors. With regard to the use of the HADS as assessment instruments, most analyses confirm the two-factorial structure, while some studies suggest other factorial solutions [29, 45]. Moreover, the thresholds for clinical elevated levels of anxiety and depression vary between studies [46]. Since there are no normative data and final solutions, we decided to use the established subscales anxiety and depression with the commonly used cut-off scores [22, 29].

Finally, as we conducted the study in Germany, the results can only be generalized to countries with socialized medicine. Cancer survivors in countries without socialized medicine may experience other stressors and challenges with regard to child rearing and work.

Conclusions

Dealing with cancer during working-age can be challenging and enhance levels of anxiety and depression. Our findings show that even up to six years after diagnosis survivors report elevated levels of anxiety compared to norm values. The results indicate the necessity of psychological screening up to years after diagnosis to identify cancer survivors at risk and may give implications for survivorship programs adjusted to the situation of cancer survivors at working-age. Additionally to physical health, survivorship programs should address psychosocial issues such as social support and family background.

Abbreviations

- FAD-GF:

-

Family Assessment Device – General Functioning Scale

- HADS-D:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – German Version

- PASW:

-

Predictive Analytics Software

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- TNM:

-

Tumor, nodes, metastases classification

- UICC:

-

Union for International Cancer Control

References

Hinz A, Krauss O, Hauss J, Höckel M, Kortmann R, Stolzenburg J, Schwarz R. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients compared with the general population. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19:522–9.

Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–51.

Stafford L, Judd F, Gibson P, Komiti A, Mann GB, Quinn M. Screening for depression and anxiety in women with breast and gynaecologic cancer: course and prevalence of morbidity over 12 months. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:2071–8.

Frick E, Tyroller M, Panzer M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital outpatient centre. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:130–6.

DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–71.

Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702.

Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Janssens ACJW, Schroder FH, de Koning HJ. Anxiety and depression after prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment: 5-year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1093–8.

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt G, Pendlebury S, Hobbs K, Wain G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:515–23.

Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Hopper JL. Age-specific norms and determinants of anxiety and depression in 731 women with breast cancer recruited through a population-based cancer registry. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:755–62.

Boyes AW, Girgis A, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C. Anxiety and depression among long-term survivors of cancer in Australia: results of a population-based survey. Med J Aust. 2009;190:S94–8.

Mehnert A, Koch U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:383–91.

Dahl AA, Haaland CF, Mykletun A, Bremnes R, Dahl O, Klepp O, Wist E, Fossa SD. Study of anxiety disorder and depression in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2389–95.

Vehling S, Mehnert A, Hartmann M, Oing C, Bokemeyer C, Oechsle K. Anxiety and depresion in long-term testicular germ cell tumor survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;38:21–5.

Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle: selected papers [German]. 1st ed. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp; 1985.

Semple CJ, McCance T. Parents’ experience of cancer who have young children: a literature review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:110–8.

Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:109–30.

Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119:2151–9.

Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM, Bennett S, Krasner C, Moy B, Younger J, Goodman A, Berkowitz R, Winer E. Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:895–903.

Slater CL. Generativity versus stagnation: an elaboration of Erikson’s adult stage of human development. J Adult Dev. 2003;10:53–65.

Winkler J, Stolzenberg H. [adjustment of the social class index for ist application in the German health survey for children and adolescents (KIGGS)]. In Wismarer Diskussionspapiere (pp.1–28). Wismar: HWS-Hochschule Wismar; 2009.

Herrmann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP. HADS-D: hospital anxiety and Drepression scale - German version. Bern: Hans-Huber Verlag; 1995.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Herrmann C. International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale--a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:17–41.

Meltzer H. Development of a common instrument for mental health. In: Nosikov A,Gudex C, Hrsg. EUROHIS: developing common instruments for health surveys. IOS Press: Amsterdam; 2003.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8 health survey (3. Aufl.). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 1999.

Ellert U, Lampert T, Ravens-Sieberer U. Measuring health-related quality of life with the SF-8. Normal sample of the German population [German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2005;48:1330–7.

Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster family assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171–80.

Beierlein V, Bultmann JC, Möller B, von Klitzing K, Flechtner HH, Resch F, Herzog W, Brähler E, Führer D, Romer G, Koch U, Bergelt C. Measuring family functioning in families with parental cancer: reliability and validity of the German adaptation of the family assessment device (FAD). J Psychosom Res. 2017;93:110–7.

Hinz A, Brähler E. Normative values for the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in the general German population. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:74–8.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associated; 1988.

Ernst JC, Beierlein V, Romer G, Moller B, Koch U, Bergelt C. Use and need for psychosocial support in cancer patients: a population-based sample of patients with minor children. Cancer. 2013;119:2333–41.

Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouse and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:721–32.

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence and psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients and their carers. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:841–8.

Mishel MH. The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1981;30:258–63.

Morrill EF, Brewer NT, O'Neill SC, Lillie SE, Dees EC, Carey LA, Rimer BK. The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:948–53.

Main DS, Nowels CT, Cavender TA, Etschmaier M, Steiner JF. A qualitative study of work and work return in cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:992–1004.

Ferrell BR, Grant MM, Funk B, Otis-Green S, Garcia N. Quality of life in breast cancer survivors as identified by focus groups. Psycho-Oncology. 1997;6:13–23.

Krauss O, Ernst J, Kuchenbecker D, Hinz A, Schwarz R. Predictors of mental disorders in patients with malignant diseases: empirical results. [German]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2007;57:273–80.

Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, Keegan THM, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Deapen D, Shnorhavorian M, Tompkins BJ, Simon M. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–62.

Koch L, Bertram H, Eberle A, Holleczek B, Schmid-Höpfner S, Waldmann A, Zeissig SR, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors—still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the cancer survivorship—a multi-regional population-based study. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23:547–54.

Castelli L, Binaschi L, Caldera P, Torta R. Depression in lung cancer patients: is the HADS an effective screening tool? Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1129–32.

O'Connor M, White K, Kristjanson LJ, Cousins K, Wilkes L. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in palliative care patients with cancer in Western Australia and new South Wales. Med J Aust. 2010;193:S44–7.

McCoubrie RC, Davies AN. Is there a correlation between spirituality and anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer? Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:379–85.

Teunissen SCCM, de Graeff A, Voest EE, de Haes JCJM. Are anxiety and depressed mood relatied to physical symptoms burden? A study in hospitalized advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2007;21:341–6.

Cosco TD, Doyle F, Ward M, McGee H. Latent structure of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: a 10-year systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:180–4.

Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-ananlysis. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1899.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all patients who participated and our collaborators at the Hamburg Cancer Registry (Head: Dr. Hentschel), and the Schleswig-Holstein Cancer Registry (Head: Prof. Dr. Katalinic) for a productive cooperation and their valuable contribution to this work. This study is part of the German multisite research project “Psychosocial Services for Children of Parents with Cancer “and is supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant # 108303). In this multisite project, the following institutions and Principal Investigators are collaborating:

- Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Hamburg-Eppendorf University Medical Center (Prof. Georg Romer);

- Institute for Medical Psychology, Hamburg Eppendorf Medical Center (Prof. Uwe Koch-Gromus);

- Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, Charité University Medical Center, Berlin (Prof. Ulrike Lehmkuhl);

- Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center, Leipzig (Prof. Kai v. Klitzing);

- Institute of Medical Psychology, University Medical Center, Leipzig (Prof. Elmar Braehler);

- Department of Psychosomatics and General Clinical Medicine, University Medical Center, Heidelberg (Prof. Wolfgang Herzog);

- Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Medical Center, Heidelberg (Prof. Franz Resch);

- Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg (Prof. Hans-Henning Flechtner).

Funding

This study was part of the German multisite research project “Psychosocial Services for Children of Parents with Cancer “and is supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant # 108303). The funding source has played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Due to ethical restrictions, the raw data underlying this manuscript are not open for the public.

Authors' contributions

LI BM GR UK and CB contributed to the conceptualization and design of this study. LI VB JCB and CB were involved in the acquisition of data. LI and CB were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising in critically, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained by the local ethic committees (Hamburg Medical Chamber and Schleswig-Holstein Medical Chamber). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Inhestern, L., Beierlein, V., Bultmann, J.C. et al. Anxiety and depression in working-age cancer survivors: a register-based study. BMC Cancer 17, 347 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3347-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3347-9