Abstract

Background

Women harboring BRCA1/2 germline mutations have high lifetime risk of developing breast/ovarian cancer. The recommendation to pursue BRCA1/2 testing is based on patient’s family history of breast/ovarian cancer, age of disease-onset and/or pathologic parameters of breast tumors. Here, we investigated if diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) independently increases risk of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation in Pakistan.

Methods

Five hundred and twenty-three breast cancer patients including 237 diagnosed ≤ 30 years of age and 286 with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer were screened for BRCA1/2 small-range mutations and large genomic rearrangements. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed at one center. Univariate and multiple logistic regression models were used to investigate possible differences in prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations according to patient and tumor characteristics.

Results

Thirty-seven percent of patients presented with TNBC. The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations was higher in patients with TNBC than non-TNBC (37 % vs. 10 %, P < 0.0001). 1 % of TNBC patients were observed to have BRCA2 mutations. Subgroup analyses revealed a larger proportion of BRCA1 mutations in TNBC than non-TNBC among patients 1) diagnosed at early-age with no family history of breast/ovarian cancer (14 % vs. 5 %, P = 0.03), 2) diagnosed at early-age irrespective of family history (28 % vs. 11 %, P = 0.0003), 3) had a family history of breast cancer (49 % vs. 12 %, P < 0.0001), and 4) those with family history of breast and ovarian cancer (81 % vs. 28 %, P = 0.0005). TNBC patients harboring BRCA1 mutations were diagnosed at a later age than non-carriers (median age at diagnosis: 30 years (range 22–53) vs. 28 years (range 18–67), P = 0.002). The association between TNBC status and presence of BRCA1 mutations was independent of the simultaneous consideration of family phenotype, tumor histology and grade in a multiple logistic regression model (Ratio of the probability of carrying BRCA1/2 mutations for TNBC vs. non-TNBC 4.23; 95 % CI 2.50–7.14; P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Genetic BRCA1 testing should be considered for Pakistani women diagnosed with TNBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Women carrying a pathogenic germline mutation in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have an increased lifetime risk of developing breast, ovarian, and several other cancers [1]. The identification of women harboring mutations in these genes is clinically important and has a significant socio-cultural impact. A major challenge faced by physicians is to identify most appropriate candidates for genetic BRCA1/2 testing since the cost of comprehensive genetic testing can be high and only 3 % of all breast cancers are attributed to BRCA1/2 germline mutations.

The decision to offer genetic testing to a breast cancer patient is currently based on family history of breast/ovarian cancer and age of disease onset. Several prediction models, which consider age of onset and family history of cancer, can be used to estimate the prior probability of having a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [2]. In addition, histopathological tumor parameters can be considered to help predict the presence of a mutation.

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and accounts for 12–15 % of all invasive breast cancer [3]. It occurs most frequently in young women and African-Americans. In Pakistan, 10-year outcome analysis of 636 breast cancer patients registered at a tertiary-care cancer center (Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre - SKMCH & RC) showed that 30.5 % (194/636) of the cases had TNBC; and majority (56.2 %) had their diagnosis made at less than 40 years of age [4]. Patients with TNBC are known to have unfavorable survival compared to patients with other breast cancer subtypes [5].

A large proportion of tumors in women with BRCA1 mutations are associated with the TNBC phenotype [6]. BRCA1/2 mutations have been identified with frequencies varying from 9.4 to 15.4 % in unselected, 17.4 to 49.1 % in younger age and 11.6 to 62 % in high risk patients with TNBC [7–15]. Studies reporting the frequency of BRCA1/2 mutations in TNBC patients from Asia have had several deficiencies including small population size [16–18], restriction of analysis to BRCA1 gene [19, 20] and evaluation limited to small-range mutations [16, 21, 22]. In order to determine the utility of genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations for women with TNBC in Pakistan, we comprehensively screened both genes for small-range mutations as well as large genomic rearrangements in a group of 523 breast cancer patients who were selected based on early-age of disease onset or family history of breast/ovarian cancer, including 192 patients diagnosed with TNBC.

Methods

Study subjects

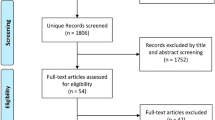

Index patients included in this study had a diagnosis of primary invasive breast cancer and were selected based on the following criteria: 1) one female breast cancer diagnosed ≤ 30 years of age; 2) two or more first- or second-degree (through a male) female relatives diagnosed with breast cancer with at least one diagnosed ≤ 50 years of age; or 3) at least one female breast cancer and one ovarian cancer at any age. A total of 573 women recruited at the SKMCH & RC in Lahore, Pakistan, from June 2001 to February 2014 fulfilled these criteria. Blood samples were obtained from all patients for the isolation of genomic DNA. Clinical, histopathologic and risk factor data were collected from all study participants. Fifty patients were excluded from the study. Reasons for exclusion are detailed in Fig. 1.

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the SKMCH & RC. All study participants signed informed written consent.

BRCA1/2 screening for small-range mutations and large genomic rearrangements

Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described [23]. One hundred and twenty-one cases comprehensively screened for BRCA1 (Genbank accession number U14680.1) and BRCA2 (Genbank accession number U43746.1) small-range mutations using protein-truncation test (PTT), single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis (SSCP) and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) analysis followed by DNA sequencing of variant fragments, and 26 BRCA1/2 mutations was described in an earlier report [23] (primer sequences are available upon request). When available, a mutation positive control was included in each set of PTT, SSCP and DHPLC analyses. A description of the BRCA1/2 screening methods is given in Supplementary methods (Additional file 1). The remaining 402 cases recruited subsequently were screened for BRCA1/2 small-range mutations using DHPLC and DNA sequencing analyses. Of these, 295 cases were previously described [24]. All patients negative for small-range BRCA1/2 mutations were further screened for large genomic rearrangements. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis was performed using probe mix P003 and P087 for BRCA1 and probe mix P045 for BRCA2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were retrieved from the pathology department; blocks were not available for 38 patients (Fig. 1). Tumor grade was assigned using the Nottingham Histologic Score. IHC analysis of ER, PR and HER2 expression was performed using standard methods [25]. Slides were interpreted by a trained breast pathologist who was blinded to BRCA1/2 mutation status. Tumors were considered negative for ER and PR if < 1 % of tumor cells demonstrated positive nuclear staining. Tumors were considered negative for HER2 if IHC score was 0 or 1+. Cases with IHC score 2+ were further subjected to fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using the PathVysion® HER2 DNA probe kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Tumors with a HER2/CEP17 ratio of > 2.2 and tumors with IHC score 3+ were considered positive.

Statistical analysis

The comparison of the distribution of clinical and histopathological characteristics between BRCA1/2 carriers and non-carriers was done using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for quantitative variables. Univariate and multiple logistic regression models were used to investigate possible differences in the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations according to patient and tumor characteristics. All statistical tests were two sided. Results were deemed statistically significant if the P value was 0.05 or less. All statistical computations were done using StatXact 4 for Windows (Cytel Inc., Cambridge, USA), SAS version 9.3 and R, version 2.1.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study participants and histopathologic parameters of tumors according to TNBC status

In total 523 unrelated Pakistani women diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer were included in the study. Of these, 45.3 % were diagnosed at young age (≤ 30 years) and 54.7 % reported a positive family history of breast/ovarian cancer. IHC analysis of ER, PR, and HER2 expression showed that 36.7 % of the patients presented with TNBC. Compared to non-TNBC patients, women with TNBC had an earlier age of diagnosis (31.6 years (range 18–67) and 35.6 years (range 19–73), respectively; P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), were more often premenopausal (91.1 % vs. 80.7 %, P = 0.002) and of Punjabi ethnicity (79.5 % vs. 69.2 %, P = 0.03). TNBC tumors were observed to have greater propensity for invasive ductal carcinoma compared to non-TNBC (96.4 % vs. 89.4 %, P = 0.004), higher tumor grade 3 (88.8 % vs. 62.9 %, P < 0.0001), and lymph node negativity (53.9 % vs. 32.5 %, P < 0.0001). Selected clinical and histopathologic characteristics of the study participants by TNBC status are shown in Table 1.

BRCA1/2 mutation prevalence in patients with TNBC and non-TNBC

The complete coding regions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were screened for small-range mutations and large genomic rearrangements in all 523 breast cancer patients. Overall, 125 cases with deleterious mutations were identified, of these, 105 occurred in BRCA1 (84 %) and 20 (16 %) in BRCA2 (Table 2). BRCA1 mutations were more frequent in patients with TNBC than in those with non-TNBC (37 % vs. 10.3 %, P < 0.0001). Majority of the mutations in patients with TNBC, 97.3 % (71/73), were detected in BRCA1; 2.7 % (2/73) had mutations in BRCA2 (P < 0.0001) (Additional file 2: Table S1). The corresponding percentage for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in non-TNBC cases was 65.4 % (34/52) and 34.6 % (18/52) (P = 0.04).

In this study, patients with TNBC harboring a BRCA1 mutation (n = 71) were older than BRCA1/2 non-carriers (n = 119) with mean age of diagnosis 32.9 years (range 22–53) and 30.9 years (range 18–67), respectively (P = 0.002, Exact Wilcoxon rank-sum test). The mean age for non-TNBC patients was 33.5 years (range 21–72) for BRCA1 carriers (n = 34), 36.8 (range 25–54) for BRCA2 carriers (n = 18) and 35.7 (range 19–73) for non-carriers (n = 279).

Subgroup analysis by family phenotype, age of diagnosis, and ethnicity

Prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in patients with TNBC and non-TNBC distributed by family phenotype, age of diagnosis, and ethnicity is detailed in Table 3. Among patients with TNBC, BRCA1 mutations were identified in 14.4 % of patients with early-onset disease (≤ 30 years), 48.7 % of patients with familial breast cancer and in 80.8 % of patients with familial breast and ovarian cancer. These frequencies were higher than the corresponding frequencies of 5.4, 12.0 and 28.0 % observed in non-TNBC patients (P = 0.03, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0005, respectively). Mutations in BRCA2 were detected in 2.6 % of patients with familial breast cancer and were absent in those with early-onset disease and familial breast and ovarian cancer. Similar frequencies were observed in non-TNBC patients; 4.1 % in patients with early-onset disease, 6.9 % in those with familial breast cancer, and 4.0 % in patients with familial breast and ovarian cancer (P = 0.09, P = 0.73 and P = 1.0, respectively).

In this study, age appeared to have a marked influence on the BRCA1 mutation frequency in familial breast/ovarian cancer patients diagnosed with TNBC. In patients over 50 years of age, the frequency was 11.1 %. For younger patients the frequency was 58.5 % for those ≤ age 30, 68.8 % for those between 31 and 40 years, and 55 % for those between 41 and 50 years. The BRCA1 mutation frequency in the age subgroups 31–40 and 41–50 years were higher in patients with TNBC than those with non-TNBC (68.8 % vs. 15.2 %, P < 0.0001 and 55 % vs. 7 %, P < 0.0001). Higher BRCA1 mutation frequency was observed in early-onset breast cancer patients regardless of family history of breast/ovarian cancer (28.2 % vs. 11 %, P = 0.0003).

In this study, analysis by ethnicity showed that BRCA1 mutation frequency in patients with TNBC belonging to the ethnic group of Punjabis, Pathans and other minor ethnic groups was higher than observed in non-TNBC patients (37.1 % vs. 12.2 %, P < 0.0001; 31.6 % vs. 5.6 %, P = 0.01 and 40 % vs. 6.2 %, P = 0.003), respectively.

Results from logistic regression analysis

BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and non-carriers were diagnosed with breast cancer at similar age. Each additional year at diagnosis translated into a 1 % lower risk of carrying BRCA1 mutations and a 1 % higher risk of harboring BRCA2 mutations, but differences did not reach statistical significance (Ratio of the probability of carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RP) = 0.99; 95 % CI 0.97–1.01; P = 0.34 and RP = 1.01; 95 % CI 0.97–1.05; P = 0.56), respectively (Table 4). Patients with a family history of breast cancer, and in particular patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer, showed 237 and 1172 % increased risk of carrying BRCA1 mutations, respectively, compared to women affected by early-onset breast cancer (Global P < 0.0001) (corresponding RP = 3.37; 95 % CI 1.96–5.80; and RP = 12.72; 95 % CI 6.22–26.0, respectively). Patients presenting with breast tumor histology of other than invasive ductal carcinoma showed a 73 % decreased risk of BRCA1 mutations (RP = 0.27; 95 % CI 0.08–0.89; P = 0.03). The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations also varied with tumor grade; women affected by grade 3 tumors showed the highest risk of carrying a BRCA1 mutation (Global P < 0.0001). In comparison with patients diagnosed with non-TNBC, patients affected by TNBC showed a 390 % higher risk of BRCA1 mutations (RP = 4.90; 95 % CI 3.09–7.77; P < 0.0001).

The association between TNBC and prevalent BRCA1 mutations was independent of the simultaneous consideration of family history, tumor histology and tumor grade in a multiple logistic regression model (Table 5). After adjustment for family history, tumor histology and tumor grade, patients affected by TNBC showed a 323 % higher risk of BRCA1 mutations than non-TNBC patients (RP = 4.23; 95 % CI 2.50–7.14; P < 0.0001).

Discussion

We report a comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Pakistani patients with TNBC and non-TNBC selected for age of onset or family history of breast/ovarian cancer. Results from our analysis showed that 97 % of all BRCA1/2 mutations in patients with TNBC were found in the BRCA1 gene. The BRCA1 mutation frequency in patients diagnosed at early age who did not report a family history of breast/ovarian cancer, patients diagnosed at early age irrespective of family history, patients with a family history of breast cancer, and patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer were approximately 3 to 4 times higher than those observed in non-TNBC patients. The diagnosis of TNBC independently increased the risk of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation. Several studies have demonstrated the relevance of TNBC status as a criterion for genetic BRCA testing [7, 13, 15, 22, 26–28]; our study confirms this observation for patients with TNBC in an Asian population from Pakistan.

Pakistani women were diagnosed with TNBC at a younger age and with higher grade tumors than non-TNBC. These findings confirm those from previous studies conducted among Asian [4, 29], North-American [30, 31] and African-American patients [31, 32]. A lower rate of lymph node involvement was observed in Pakistani patients with TNBC than non-TNBC, which is in line with previous data from other Asian [29, 33, 34] and North-American studies [35]. A higher rate was observed in one study among North-Americans [30], while no difference was observed in a European study [36]. The discrepant data may be explained by differences in the study design or the IHC cut-off values for ER and PR negativity. While data from the study of Dent and colleagues were based on unselected cases and a cut-off for ER/PR negativity of < 10 % of tumor cells staining positive, the Pakistani study participants were selected for young age or family history of breast/ovarian cancer and the threshold for negative ER/PR result was < 1 % of tumor cells staining positive.

In Pakistan, 42 distinct mutations including 40 in BRCA1 and two in BRCA2 were identified in patients with TNBC. Of these mutations, 17 mutations (including five mutations previously identified in Pakistani breast/ovarian cancer patients) are population-specific as they were not identified in other populations [23, 37]. Twenty-five recurrent BRCA1/2 mutations (including 18 mutations previously reported in Pakistani breast/ovarian cancer patients) have also been described elsewhere in the world, indicating that majority of mutations found in the current study did not differ from those previously reported in Pakistan or elsewhere.

In most Western studies, the mean age of diagnosis of TNBC in BRCA1 mutation carriers was significantly lower than in non-carriers [7, 13, 15]. No difference in the age of TNBC diagnosis between BRCA1 carriers and non-carriers was detected in some studies on early-onset or familial cases from the US [6] and Singapore [18]. In contrast, Pakistani BRCA1 carriers were two years older at TNBC diagnosis than non-carriers implying that other environmental or genetic factors may be operant in TNBC in this group of women. It is also possible that the diverse results are due to differences in study design, selection criteria or ethnicity.

Pakistani women are usually diagnosed with breast cancer below 40 years of age [38] and often present with advanced disease [39]. In the current study, BRCA1 mutations were identified in 14.4 % of early-onset patients with TNBC, who had no family history of breast/ovarian cancer. Lower BRCA1 mutations frequencies of 4.3, 7.4 and 8.7 % were observed in other studies conducted in China, Italy, and the UK, respectively [9, 22, 40]. However, given the small number of patients with TNBC diagnosed < 30 years of age investigated in these studies (n = ≤ 30), the percentages may not be truly representative.

In the present study BRCA1/2 mutations were identified in 58.8 % of patients with TNBC, who reported a family history of breast/ovarian cancer. In other Asian studies performed in China, Malaysia, and Korea and also in Caucasian studies conducted in Australia, Europe, and the United States, the mutation frequencies were similar or lower ranging from 20.8 to 59.5 % [17, 22, 26, 41, 42] and 11.6 to 62 % [7, 8, 10–13, 15], respectively. The varying mutation frequencies obtained in these studies may be explained by differences in sample size, mutation detection assays used, or ethnic origin of study participants.

The low frequency of BRCA2 mutations detected in our study is in keeping with prior reports and suggests that BRCA2 may not play an important role in the development of early-onset TNBC. With the exception of one small German study that included 30 patients with TNBC [11], BRCA2 mutations were less common than BRCA1 mutations in several studies among patients of European or North-American origin [9, 14, 15, 28] and patients from Asia [22, 26] including the present one. These data indicate the tendency for BRCA1 carriers to primarily develop TNBC compared to BRCA2 carriers, which most commonly develop ER positive breast tumors [43].

Recommendations for genetic BRCA1/2 testing for patients with TNBC are not universally accepted and vary between professional societies [13] and studies [15, 22, 26, 28]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that women with TNBC diagnosed before or at age 60 should be considered for genetic BRCA1/2 testing (NCCN Guidelines), while the guidelines of the European Society of Medical Oncology [44] and the Cancer Institute New South Wales (https://www.eviq.org.au) recommend testing if TNBC is diagnosed under the ages of 50 and 40 years, respectively. Moreover, testing was suggested to Mexican patients affected by disease below age 60 [28], below or at age 50 to patients from the UK [27], China [22] and Malaysia [26], and irrespective of age to Polish and Australian patients [15]. The high frequency of BRCA1 mutations in Pakistani patients with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer diagnosed with TNBC below or at age 50 and in early-onset patients diagnosed before or at age 30 irrespective of family history suggest that genetic testing should be considered for these groups of women. Testing women with TNBC diagnosed below age 50 has previously been shown to be a cost-effective strategy [45]. Given the financial burden these considerations are of particular importance for developing countries like Pakistan.

Recently, deleterious mutations in 14 known breast cancer susceptibility genes including BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51C were identified at a frequency of 3.7 % in a large series of 1,824 patients with TNBC unselected for family history of breast cancer [7]. As in the study reported by Couch and colleagues, no mutations in the CHEK2 and TP53 genes were observed in two Pakistani studies among 374 (including 103 with TNBC) [46] and 105 (including 47 with TNBC) breast/ovarian cancer patients [47], respectively. Recently, a deleterious mutation (c.5101C > T) in the FANCM gene was identified in BRCA1/2-negative familial patients with TNBC from Finland [48]. This mutation was not detected in a Pakistani study that included 117 patients with TNBC [49].

There are several limitations of our study. First, we have screened only patients with TNBC, who were selected for early-age of onset (≤ 30 years) or family history of breast/ovarian cancer. Hence the selection of high-risk patients may explain the higher BRCA1/2 mutation frequency observed in our study compared to those that evaluated unselected TNBC patients. Secondly, we did not use BRCA1/2 prediction models. However, given the previously observed inaccuracy of these algorithms in predicting risk precisely in Asian populations, limits the usefulness of these algorithms and warrants further investigation [50, 51]. Strengths of the present study include the sample size (N = 523) comprising sufficiently larger number of early-onset breast cancer (≤ 30 years) women (n = 303) with TNBC (n = 131) or non-TNBC (n = 172) compared to studies reported from Asia previously. Additionally, our study evaluated the complete coding regions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that were comprehensively screened for both, small-range mutations and large genomic rearrangements. Screening for both types of mutations has only been reported in few studies performed previously [10, 26]. Yet another strength was that all data were generated at a single institution, therefore no variability was introduced by using different methods for tumor grading and IHC analysis and evaluation and the pathologist, who evaluated the ER, PR, and HER2 status, was blinded to the mutation status. Finally, the majority of study participants (73.4 %) were recruited within one year of disease presentation, which minimizes the likelihood of survival bias.

Conclusions

We found high prevalence and predominance of BRCA1 germline mutations in Pakistani women with TNBC compared to patients with non-TNBC presenting before or at age 30 irrespective of family history of breast/ovarian cancer and before or at age 50 with familial breast cancer or familial breast and ovarian cancer. The association between TNBC status and presence of BRCA1 mutations was independent of the simultaneous consideration of family phenotype, tumor histology, and tumor grade in a multiple logistic regression model. Our data suggest that TNBC status should be incorporated as a criterion for genetic BRCA1 testing in Pakistan. Identification of individuals with BRCA1 germline mutations will enable physicians to optimize cancer management for this high risk phenotype.

Abbreviations

- DHPLC:

-

Denaturing High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

- ER:

-

Estrogen Receptor

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded

- HER2:

-

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemical

- MLPA:

-

multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- NCCN:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PR:

-

Progesterone Receptor

- SKMCH & RC:

-

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore, Pakistan

- TNBC:

-

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

References

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, Bishop DT, Weber B, Lenoir G, Chang-Claude J, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:676–89.

Antoniou AC, Easton DF. Risk prediction models for familial breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2006;2:257–74.

Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–48.

Bhatti AB, Khan AI, Siddiqui N, Muzaffar N, Syed AA, Shah MA, Jamshed A. Outcomes of triple-negative versus non-triple-negative breast cancers managed with breast-conserving therapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2577–81.

Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, Andre F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1275–81.

Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, Valero V, Amos CI, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hortobagyi GN, Arun BK. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4282–8.

Couch FJ, Hart SN, Sharma P, Toland AE, Wang X, Miron P, Olson JE, Godwin AK, Pankratz VS, Olswold C, et al. Inherited mutations in 17 breast cancer susceptibility genes among a large triple-negative breast cancer cohort unselected for family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;33:304–11.

Bayraktar S, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Liu D, Tasbas T, Akar U, Litton JK, Lin E, Albarracin CT, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Outcome of triple-negative breast cancer in patients with or without deleterious BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:145–53.

Evans DG, Howell A, Ward D, Lalloo F, Jones JL, Eccles DM. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in triple negative breast cancer. J Med Genet. 2011;48:520–2.

Hartman AR, Kaldate RR, Sailer LM, Painter L, Grier CE, Endsley RR, Griffin M, Hamilton SA, Frye CA, Silberman MA, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations in an unselected population of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:2787–95.

Meyer P, Landgraf K, Hogel B, Eiermann W, Ataseven B. BRCA2 mutations and triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38361.

Pern F, Bogdanova N, Schurmann P, Lin M, Ay A, Langer F, Hillemanns P, Christiansen H, Park-Simon TW, Dork T. Mutation analysis of BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 and BRD7 in a hospital-based series of German patients with triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47993.

Sharma P, Klemp JR, Kimler BF, Mahnken JD, Geier LJ, Khan QJ, Elia M, Connor CS, McGinness MK, Mammen JM, et al. Germline BRCA mutation evaluation in a prospective triple-negative breast cancer registry: implications for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer syndrome testing. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:707–14.

Young SR, Pilarski RT, Donenberg T, Shapiro C, Hammond LS, Miller J, Brooks KA, Cohen S, Tenenholz B, Desai D, et al. The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations among young women with triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:86.

Wong-Brown MW, Meldrum CJ, Carpenter JE, Clarke CL, Narod SA, Jakubowska A, Rudnicka H, Lubinski J, Scott RJ. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:71–80.

Li YT, Ni D, Yang L, Zhao Q, Ou JH. The prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations of triple-negative breast cancer patients in Xinjiang multiple ethnic region of China. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:35.

Seong MW, Kim KH, Chung IY, Kang E, Lee JW, Park SK, Lee MH, Lee JE, Noh DY, Son BH, et al. A multi-institutional study on the association between BRCA1/BRCA2 mutational status and triple-negative breast cancer in familial breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:63–9.

Wong ES, Shekar S, Chan CH, Hong LZ, Poon SY, Silla T, Lin C, Kumar V, Davila S, Voorhoeve M, et al. Predictive factors for BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing in an Asian clinic-based population. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134408.

Chen W, Pan K, Ouyang T, Li J, Wang T, Fan Z, Fan T, Lin B, Lu Y, You W, et al. BRCA1 germline mutations and tumor characteristics in Chinese women with familial or early-onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:55–60.

Kuo WH, Lin PH, Huang AC, Chien YH, Liu TP, Lu YS, Bai LY, Sargeant AM, Lin CH, Cheng AL, et al. Multimodel assessment of BRCA1 mutations in Taiwanese (ethnic Chinese) women with early-onset, bilateral or familial breast cancer. J Hum Genet. 2012;57:130–8.

Ou J, Wu T, Sijmons R, Ni D, Xu W, Upur H. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in breast cancer women of multiple ethnic region in northwest China. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16:50–4.

Wang C, Zhang J, Wang Y, Ouyang T, Li J, Wang T, Fan Z, Fan T, Lin B, Xie Y. Prevalence of BRCA1 mutations and responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among BRCA1 carriers and non-carriers with triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:523–8.

Rashid MU, Zaidi A, Torres D, Sultan F, Benner A, Naqvi B, Shakoori AR, Seidel-Renkert A, Farooq H, Narod S, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Pakistani breast and ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2832–9.

Rashid MU, Muzaffar M, Khan FA, Kabisch M, Muhammad N, Faiz S, Loya A, Hamann U. Association between the BsmI polymorphism in the vitamin D receptor gene and breast cancer risk: results from a Pakistani case–control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141562.

Chen X, Cho DB, Yang PC. Double staining immunohistochemistry. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2:241–5.

Phuah SY, Looi LM, Hassan N, Rhodes A, Dean S, Taib NA, Yip CH, Teo SH. Triple-negative breast cancer and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) loss are predictors of BRCA1 germline mutations in women with early-onset and familial breast cancer, but not in women with isolated late-onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R142.

Robertson L, Hanson H, Seal S, Warren-Perry M, Hughes D, Howell I, Turnbull C, Houlston R, Shanley S, Butler S, et al. BRCA1 testing should be offered to individuals with triple-negative breast cancer diagnosed below 50 years. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1234–8.

Villarreal-Garza C, Weitzel JN, Llacuachaqui M, Sifuentes E, Magallanes-Hoyos MC, Gallardo L, Varez-Gomez RM, Herzog J, Castillo D, Royer R, et al. The prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among young Mexican women with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:389–94.

Lee JA, Kim KI, Bae JW, Jung YH, An H, Lee ES. Triple negative breast cancer in Korea-distinct biology with different impact of prognostic factors on survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:177–87.

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–34.

Phipps AI, Buist DS, Malone KE, Barlow WE, Porter PL, Kerlikowske K, Li CI. Family history of breast cancer in first-degree relatives and triple-negative breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:671–8.

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–502.

Lin C, Chien SY, Chen LS, Kuo SJ, Chang TW, Chen DR. Triple negative breast carcinoma is a prognostic factor in Taiwanese women. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:192.

Xue C, Wang X, Peng R, Shi Y, Qin T, Liu D, Teng X, Wang S, Zhang L, Yuan Z. Distribution, clinicopathologic features and survival of breast cancer subtypes in Southern China. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1679–87.

Tischkowitz M, Brunet JS, Begin LR, Huntsman DG, Cheang MC, Akslen LA, Nielsen TO, Foulkes WD. Use of immunohistochemical markers can refine prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:134.

Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Green AR, Lee AH, Robertson JF, Ellis IO. Prognostic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:25–32.

Liede A, Malik IA, Aziz Z, De Los Rios P, Kwan E, Narod SA. Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast and ovarian cancer in Pakistan. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:595–606.

Usmani K, Khanum A, Afzal H, Ahmad N. Breast carcinoma in Pakistani women. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1996;15:251–3.

Khokher S, Qureshi MU, Riaz M, Akhtar N, Saleem A. Clinicopathologic profile of breast cancer patients in Pakistan: ten years data of a local cancer hospital. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:693–8.

Palomba G, Budroni M, Olmeo N, Atzori F, Ionta MT, Pisano M, Tanda F, Cossu A, Palmieri G. Triple-negative breast cancer frequency and type of mutation: Clues from Sardinia. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:948–52.

Zhang J, Pei R, Pang Z, Ouyang T, Li J, Wang T, Fan Z, Fan T, Lin B, Xie Y. Prevalence and characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Chinese women with familial breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:421–8.

Yip CH, Taib NA, Choo WY, Rampal S, Thong MK, Teo SH. Clinical and pathologic differences between BRCA1-, BRCA2-, and non-BRCA-associated breast cancers in a multiracial developing country. World J Surg. 2009;33:2077–81.

Bane AL, Beck JC, Bleiweiss I, Buys SS, Catalano E, Daly MB, Giles G, Godwin AK, Hibshoosh H, Hopper JL, et al. BRCA2 mutation-associated breast cancers exhibit a distinguishing phenotype based on morphology and molecular profiles from tissue microarrays. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:121–8.

Balmana J, Diez O, Rubio IT, Cardoso F. BRCA in breast cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2011;22 Suppl 6:vi31–4.

Kwon JS, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Young D, Sun CC, Daniels MS, Lu KH, Arun B. Expanding the criteria for BRCA mutation testing in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4214–20.

Rashid MU, Muhammad N, Faisal S, Amin A, Hamann U. Constitutional CHEK2 mutations are infrequent in early-onset and familial breast/ovarian cancer patients from Pakistan. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:312–8.

Rashid MU, Gull S, Asghar K, Muhammad N, Amin A, Hamann U. Prevalence of TP53 germ line mutations in young Pakistani breast cancer patients. Fam Cancer. 2012;11:307–11.

Kiiski JI, Pelttari LM, Khan S, Freysteinsdottir ES, Reynisdottir I, Hart SN, Shimelis H, Vilske S, Kallioniemi A, Schleutker J, et al. Exome sequencing identifies FANCM as a susceptibility gene for triple-negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15172–7.

Rashid MU, Muhammad N, Khan FA, Hamann U. Absence of the FANCM c.5101C > T mutation in BRCA1/2-negative triple-negative breast cancer patients from Pakistan. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:229–30.

Kang E, Park SK, Yang JJ, Park B, Lee MH, Lee JW, Suh YJ, Lee JE, Kim HA, Oh SJ, et al. Accuracy of BRCA1/2 mutation prediction models in Korean breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:1189–97.

Thirthagiri E, Lee SY, Kang P, Lee DS, Toh GT, Selamat S, Yoon SY, Taib NA, Thong MK, Yip CH, et al. Evaluation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and risk-prediction models in a typical Asian country (Malaysia) with a relatively low incidence of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R59.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study subjects for their participation in this study. We thank clinicians for the recruitment of study subjects.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre and the German Cancer Research Center.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the manuscript or additional files.

Authors’ contributions

MUR contributed to conception and design of the study, patient recruitment and data acquisition. In addition, he was involved in data analysis, interpretation and in drafting and revising the manuscript. NM performed the molecular analyses and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. SB was involved in collection of pathology specimen and data acquisition. SF was involved in patient recruitment and data acquisition. MT was involved in the retrieval of FFPE blocks and further performed IHC analysis of ER, PR and HER2 expression. JLB performed statistical analysis and contributed to data interpretation. AA was involved in the recruitment of study subjects, clinical data collection and revising the manuscript. AL was involved in the pathological data acquisition and interpretation. UH contributed to conception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (SKMCH & RC), Lahore, Pakistan. The ethics committee name is the “Institutional Review Board”. The approval number is ONC-BRCA-001. All study participants signed informed written consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supplementary methods BRCA mutation analyses. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Deleterious BRCA1/2 germline mutations in Pakistani patients with TNBC. (DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rashid, M.U., Muhammad, N., Bajwa, S. et al. High prevalence and predominance of BRCA1 germline mutations in Pakistani triple-negative breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 16, 673 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2698-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2698-y