Abstract

Background

Primary melanocytic neoplasms are rare in the pediatric age. Among them, the pattern of neoplastic meningitis represents a peculiar diagnostic challenge since neuroradiological features may be subtle and cerebrospinal fluid analysis may not be informative. Clinical misdiagnosis of neoplastic meningitis with tuberculous meningitis has been described in few pediatric cases, leading to a significant delay in appropriate management of patients. We describe the case of a child with primary leptomeningeal melanoma (LMM) that was initially misdiagnosed with tuberculous meningitis. We review the clinical and molecular aspects of LMM and discuss on clinical and diagnostic implications.

Case presentation

A 27-month-old girl with a 1-week history of vomiting with mild intermittent strabismus underwent Magnetic Resonance Imaging, showing diffuse brainstem and spinal leptomeningeal enhancement. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable. Antitubercular treatment was started without any improvement. A spinal intradural biopsy was suggestive for primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis. Chemotherapy was started, but general clinical conditions progressively worsened and patient died 11 months after diagnosis. Molecular investigations were performed post-mortem on tumor tissue and revealed absence of BRAFV600E, GNAQQ209 and GNA11Q209 mutations but the presence of a NRASQ61K mutation.

Conclusions

Our case adds some information to the limited experience of the literature, confirming the presence of the NRASQ61K mutation in children with melanomatosis. To our knowledge, this is the first case of leptomeningeal melanocytic neoplasms (LMN) without associated skin lesions to harbor this mutation. Isolated LMN presentation might be insidious, mimicking tuberculous meningitis, and should be suspected if no definite diagnosis is possible or if antitubercular treatment does not result in dramatic clinical improvement. Leptomeningeal biopsy should be considered, not only to confirm diagnosis of LMN but also to study molecular profile. Further molecular profiling and preclinical models will be pivotal in testing combination of target therapy to treat this challenging disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary melanocytic neoplasms are rare in the pediatric age and may present with a wide spectrum of clinical and pathological features [1]. Among them, the pattern of neoplastic meningitis represents a peculiar diagnostic challenge since the neuroradiological features may be subtle and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may not be informative [1]. Clinical misdiagnosis of neoplastic meningitis with tuberculous meningitis has been described in few pediatric cases, leading to a significant delay in appropriate management of patients (Table 1) [2–7].

We describe the case of a child with primary leptomeningeal melanoma (LMM) that was initially misdiagnosed with tuberculous meningitis. We review clinical and molecular aspects of LMM and discuss clinical and diagnostic implications.

Case presentation

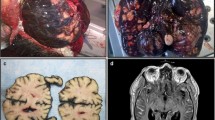

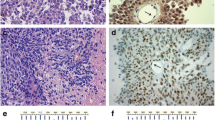

A 27- month-old girl was referred to Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital in 2009 after a 1-week history of vomiting associated to mild intermittent strabismus. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed bilateral papilledema. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed diffuse brainstem and spinal leptomeningeal enhancement (Fig. 1a–c). CSF analysis was unremarkable. Tuberculosis (TB) was not confirmed by a complete work-up. Nonetheless, antitubercular treatment was started based on the MRI findings. After 10 days the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit for a salt wasting syndrome. A new MRI demonstrated hydrocephalus (Fig. 1d) and progression of leptomeningeal enhancement (Fig. 1e–g). A new CSF examination was done and showed neoplastic cells with large cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2) positive for S100. Therefore, antitubercular therapy was discontinued and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed because of the progression of neurological symptoms. Moreover, a spinal intradural biopsy was performed: histological examination showed pleomorphic cells with vesicular nuclei, eosinophilic nuclear pseudoinclusion and moderate cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry showed intense positivity for MelanA, suggesting the diagnosis of primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis. No signs of cutaneous melanosis were observed. Chemotherapy was started, including temozolomide, cis-platinum, vindesine and peg-interferon alfa-2b. MRI was obtained every two months showing stable disease until the sixth course of chemotherapy when progression was found. At that time, radiation was associated to peg-interferon alfa-2b but the tumor rapidly spread to chest and abdomen. General clinical conditions progressively worsened and patient died 11 months after diagnosis. Molecular investigations were performed post-mortem on tumor tissue and revealed absence of BRAFV600E, GNAQQ209 and GNA11Q209 mutations but the presence of a NRASQ61K mutation.

Clinical onset MRI (a, b, c). Follow-up MRI (d, e, f, g). T1 axial basal image (a): no evidence of LMM’s typical hyperintensities. T1 Contrast enhancement images (b, c): intense base and peri-spinal leptomeningeal enhancement and nodular pontine enhancing lesion (white arrow); (e, f, g) increase of enhancing lesions. T1 axial (a, d): progressive hydrocephalus

Conclusions

Primary leptomeningeal melanocytic neoplasms (LMN) can be focal (melanomas) or diffuse (melanomatosis) [8]. Since the first description by Virchow in 1859 [9], primary LMM has been reported in few hundreds of patients, mainly adults, with peak incidence in the fourth decade of life [2, 10, 11]. Pediatric experience is extremely limited, accounting for about 0.1 % of central nervous system tumors, this affecting the diagnostic approach and clinical management of patients. During embryogenesis, melanocytic precursors spread from the neural crest to the skin. Few cells can also be found in mucosae, eyes and leptomeninges, explaining primary extracutaneous localizations of melanomas.

Isolated LMNs are a challenging diagnosis in children because they are usually found in association to cutaneous melanomatosis. As previously reported, neurologic signs and symptoms of primary LMM are nonspecific, including seizures, psychiatric disturbances, and signs and symptoms of raised intracranial pressure, often with rapid evolution and fatal course [2]. Unlike most other cerebral tumors, the classic MRI appearance of LMM consists in high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, depending on the presence of free paramagnetic radicals from melanin. Nonetheless, different signal patterns may be observed because of intratumoral hemorrhage [11]. A milestone in the characterization of cutaneous melanoma is the finding of the BRAFV600E mutation in over 50 % of cases. Few molecular data are available about LMN making diagnosis challenging both on the clinical and pathological side [12].

Recent data suggest the presence of specific mutations in diffuse melanomatosis. Interestingly, different mutations have been found in adults (GNAQ and GNA11 mutations) and children (NRASQ61K), with BRAFV600E mutation being observed in only 2 % of adult cases. In the largest series of children with cutaneous melanomatosis, 51 out of 66 were found to have the NRASQ61K mutation in their lesions [13]. Notably, in children with the neurocutaneous form (12 out of 16), the same mutation was found in leptomeningeal lesions suggesting a common origin of neoplastic precursors [14–16]. It has been suggested that a post-zygotic NRAS mutation of neural crest cells during embryogenesis, before migration to skin and leptomeninges, might condition a NRAS mosaicism in the same organism [17]. Nonetheless, mutations occurring before commitment to the neural crest lineage might explain the detection of the same NRAS mutation in tumors other than melanocytic. Interestingly, a NRASQ61R mutation has been reported in a spinal neurocristic hamartoma associated to NCM and leptomeningeal melanocytosis by Kinsler et al. Other observed tumors include meningioma and choroid plexus papilloma. Shih et al. reported a NRASG13R mutation in a primary mesenchimal brain neoplasm [18]. Invariably, the same mutation was documented in associated CMN but the observation of a germline single-nucleotide polymorphism of the MET gene suggests the possibility of a second hit to condition the clinical picture. In fact, NRAS mutations do not result in melanoma according to in vitro and in vivo preclinical models and to the evidence of mutated cells in CMN [19]. Possible co-operators in melanoma development include MET and CDKN2A [15, 20, 21].

Our case adds some information to the limited experience of the literature, confirming the presence of the NRASQ61 mutation in children with meningeal melanomatosis. To our knowledge, this is the first case of LMN without associated skin lesions to harbor this mutation. Despite thorough clinical examination we cannot exclude the possibility of cutaneous melanoma having been overlooked in our patient. Nonetheless, cutaneous melanomas have also been described to regress spontaneously. Our child was initially treated for tuberculous meningitis based on MRI picture. LMNs have typically been described to show T1 hyperintensity and T2 hypointensity on baseline MRI [22]. Our patient did not show these features, making the diagnosis of infective meningitis more appealing in the first instance, even in presence of a negative work-up for TB. We would recommend reconsideration of diagnosis in case of suspect TB showing clinical-radiological progression during anti-tubercular treatment. Biopsy should be considered, not only to confirm diagnosis of LMN but also to study molecular profile and guide target therapy. NRAS inhibitors are not currently available but downstream pathways, such as MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR constitute possible targets. In fact, promising results have been reported both in vitro and in vivo [16, 23–27]. Multi-target combinational approaches might help overcome resistance to treatment, however their clinical significance remains to be further determined [23, 24, 27–29].

Primary LMNs constitute a wide family of rare tumors. Peculiar pathogenetic mutations have been described in the adult (GNAQ and GNA11) and pediatric (NRAS) population. Most LMN present in association to cutaneous melanosis (NCM, CMN) and, in fact, a common molecular signature has been demonstrated in these cell populations. Our case is, to our knowledge, the first report of a LMN not associated to cutaneous findings but sharing the same NRASQ61 mutation widely reported in the literature. Isolated LMN presentation might be insidious, mimicking TB meningitis, and should be suspected if no definite diagnosis is possible or if anti-TB treatment does not result in dramatic clinical improvement. Further molecular profiling and preclinical models will be pivotal in testing combination of target therapy to treat this challenging disease.

Abbreviations

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LMM, leptomeningeal melanoma; LMN, leptomeningeal melanocytic neoplasms; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis

References

Perry A, Dehner LP. Meningeal tumors of childhood and infancy. An update and literature review. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:386–408.

Makin GW, Eden OB, Lashford LS, Moppett J, Gerrard MP, Davies HA, Powell CV, Campbell AN, Frances H. Leptomeningeal melanoma in childhood. Cancer. 1999;86:878–86.

Nicolaides P, Newton RW, Kelsey A. Primary malignant melanoma of meninges: atypical presentation of subacute meningitis. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;12:172–4.

Selcuk N, Elevli M, Inanc D, Arslan H. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor mimicking tuberculous meningitis. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:325–6.

Demir HA, Varan A, Akyüz C, Söylemezoğlu F, Cila A, Büyükpamukçu M. Spinal low-grade neoplasm with leptomeningeal dissemination mimicking tuberculous meningitis in a child. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27:187–92.

Kosker M, Sener D, Kilic O, Hasiloglu ZI, Islak C, Kafadar A, Batur S, Oz B, Cokugras H, Akcakaya N, Camcioglu Y. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis mimicking tuberculous meningitis. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:NP171–5.

Erdogan EB, Asa S, Yilmaz Aksoy S, Ozhan M, Aliyev A, Halac M. Primary spinal leptomeningeal gliomatosis in a 3-year-old boy revealed with MRI and FDG PET/CT mimicking tuberculosis meningitis. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2014;33:127–8.

Brat DJ, Perry A. Melanocytic lesions. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Weistler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Lyon: Intl. Agency for Research; 2007.

Virchow R. Pigment und diffuse melanose der arachnoides. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1859;16:180.

Hsieh YY, Yang ST, Li WH, Hu CJ, Wang LS. Primary Leptomeningeal Melanoma Mimicking Meningitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Oncol. 2014. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.0264.

Allcutt D, Michowiz S, Weitzman S, Becker L, Blaser S, Hoffman HJ, Humphreys RP, Drake JM, Rutka JT. Primary leptomeningeal melanoma: an unusually aggressive tumor in childhood. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:721–9.

Küsters-Vandevelde HV, Küsters B, van Engen-van Grunsven AC, Groenen PJ, Wesseling P, Blokx WA. Primary melanocytic tumors of the central nervous system: a review with focus on molecular aspects. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:209–26.

Salgado CM, Basu D, Nikiforova M, Bauer BS, Johnson D, Rundell V, Grunwaldt LJ, Reyes-Múgica M. BRAF mutations are also associated with neurocutaneous melanocytosis and large/giant congenital melanocytic nevi. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2015;18(1):1–9.

Pedersen M, Küsters-Vandevelde HV, Viros A, Groenen PJ, Sanchez-Laorden B, Gilhuis JH, van Engen-van Grunsven IA, Renier W, Schieving J, Niculescu-Duvaz I, Springer CJ, Küsters B, Wesseling P, Blokx WA, Marais R. Primary melanoma of the CNS in children is driven by congenital expression of oncogenic NRAS in melanocytes. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(4):458–69.

Kinsler VA, Thomas AC, Ishida M, Bulstrode NW, Loughlin S, Hing S, Chalker J, McKenzie K, Abu-Amero S, Slater O, Chanudet E, Palmer R, Morrogh D, Stanier P, Healy E, Sebire NJ, Moore GE. Multiple congenital melanocytic nevi and neurocutaneous melanosis are caused by postzygotic mutations in codon 61 of NRAS. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(9):2229–36.

Küsters-Vandevelde HV, Willemsen AE, Groenen PJ, Küsters B, Lammens M, Wesseling P, Djafarihamedani M, Rijntjes J, Delye H, Willemsen MA, van Herpen CM, Blokx WA. Experimental treatment of NRAS-mutated neurocutaneous melanocytosis with MEK162, a MEK-inhibitor. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:41.

Hafner C, Groesser L. Mosaic RASopathies. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(1):43–50.

Shih F, Yip S, McDonald PJ, Chudley AE, Del Bigio MR. Oncogenic codon 13 NRAS mutation in a primary mesenchymal brain neoplasm and nevus of a child with neurocutaneous melanosis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:140.

Bauer J, Curtin JA, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Congenital melanocytic nevi frequently harbor NRAS mutations but no BRAF mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(1):179–82.

Chin L, Pomerantz J, Polsky D, Jacobson M, Cohen C, Cordon-Cardo C, Horner 2nd JW, DePinho RA. Cooperative effects of INK4a and ras in melanoma susceptibility in vivo. Genes Dev. 1997;11(21):2822–34.

Ackermann J, Frutschi M, Kaloulis K, McKee T, Trumpp A, Beermann F. Metastasizing melanoma formation caused by expression of activated N-RasQ61K on an INK4a-deficient background. Cancer Res. 2005;65(10):4005–11.

Smith AB, Rushing EJ, Smirniotopoulos JG. Pigmented lesions of the central nervous system: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(5):1503–24.

Nagashima Y, Miyagi Y, Aoki I, Funabiki T, Ikuta K, Umeda M, Kuchino Y, Misugi K. Establishment and characterization of a malignant melanoma cell line (YP-MEL) derived from a patient with neurocutaneous melanosis. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190(2):178–85.

Kelleher FC, McArthur GA. Targeting NRAS in melanoma. Cancer J. 2012;18(2):132–6.

von Euw E, Atefi M, Attar N, Chu C, Zachariah S, Burgess BL, Mok S, Ng C, Wong DJ, Chmielowski B, Lichter DI, Koya RC, McCannel TA, Izmailova E, Ribas A. Antitumor effects of the investigational selective MEK inhibitor TAK733 against cutaneous and uveal melanoma cell lines. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:22.

Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, Agarwala SS, van Herpen CM, Queirolo P, Blank CU, Hauschild A, Beck JT, St-Pierre A, Niazi F, Wandel S, Peters M, Zubel A, Dummer R. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):249–56.

Ruan Y, Kovalchuk A, Jayanthan A, Lun X, Nagashima Y, Kovalchuk O, Wright Jr JR, Pinto A, Kirton A, Anderson R, Narendran A. Druggable targets in pediatric neurocutaneous melanocytosis: Molecular and drug sensitivity studies in xenograft and ex vivo tumor cell culture to identify agents for therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(6):822–31.

Roberts PJ, Usary JE, Darr DB, Dillon PM, Pfefferle AD, Whittle MC, Duncan JS, Johnson SM, Combest AJ, Jin J, Zamboni WC, Johnson GL, Perou CM, Sharpless NE. Combined PI3K/mTOR and MEK inhibition provides broad antitumor activity in faithful murine cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(19):5290–303.

Rebecca VW, Alicea GM, Paraiso KH, Lawrence H, Gibney GT, Smalley KS. Vertical inhibition of the MAPK pathway enhances therapeutic responses in NRAS-mutant melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(6):1154–8.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the child’s parents, who gave their informed consent for publication.

Funding

No funding was received for the present study.

Availability of data and materials

We considered the literature and articles that are available on PubMed. Radiological and histological specific images of our case are loaded as files in addition to text. We are available for further information or data, please contact us.

Authors' contributions

GA drafted the manuscript. MDDP, LDS, AS, LM, LL, AntM and AC were involved in clinical care of the patient and contributed to the draft. RDV performed cytological and histological analysis and contributed to the draft. MA, FG and MG carried out the molecular genetic studies and contributed to the draft. LM, LS and DL performed imaging and contributed to the draft. AngM conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm that consent for publication has be obtained from child’s parents.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The manuscript is a retrospective case report, that does not require ethics committee approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Angelino, G., De Pasquale, M.D., De Sio, L. et al. NRASQ61K mutated primary leptomeningeal melanoma in a child: case presentation and discussion on clinical and diagnostic implications. BMC Cancer 16, 512 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2556-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2556-y