Abstract

Background

Metastasis of colorectal cancer (CRC) is directly linked to patient survival. We previously identified the novel gene Metastasis Associated in Colon Cancer 1 (MACC1) in CRC and demonstrated its importance as metastasis inducer and prognostic biomarker. Here, we investigate the geographic expression pattern of MACC1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma and tumor buds in correlation with clinicopathological and molecular features for improvement of survival prognosis.

Methods

We performed geographic MACC1 expression analysis in tumor center, invasive front and tumor buds on whole tissue sections of 187 well-characterized CRCs by immunohistochemistry. MACC1 expression in each geographic zone was analyzed with Mismatch repair (MMR)-status, BRAF/KRAS-mutations and CpG-island methylation.

Results

MACC1 was significantly overexpressed in tumor tissue as compared to normal mucosa (p < 0.001). Within colorectal adenocarcinomas, a significant increase of MACC1 from tumor center to front (p = 0.0012) was detected. MACC1 was highly overexpressed in 55% tumor budding cells. Independent of geographic location, MACC1 predicted advanced pT and pN-stages, high grade tumor budding, venous and lymphatic invasion (p < 0.05). High MACC1 expression at the invasive front was decisive for prediction of metastasis (p = 0.0223) and poor survival (p = 0.0217). The geographic pattern of MACC1 did not correlate with MMR-status, BRAF/KRAS-mutations or CpG-island methylation.

Conclusion

MACC1 is differentially expressed in CRC. At the invasive front, MACC1 expression predicts best aggressive clinicopathological features, tumor budding, metastasis formation and poor survival outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is still one of the most frequent malignancies in the Western world with more than 1 million new cases every year. The life time risk to suffer from CRC is about 5% in developed countries [1,2]. Metastasis of primary colorectal tumors is directly linked to patient survival and accounts for about 90% of patient deaths. About half of the subjects with CRC can be cured by surgery and multimodal treatment, but therapy options are limited particularly for metastasized patients. This is demonstrated by 5-year-survival rates of higher than 90% for early stage patients, 65% for patients with regional lymph node metastases, and less than 10% in patients with metastatic disease [2]. Synchronous distant metastases were already observed in about 30% of CRC patients, and at least a further third will develop metachronous metastases later, despite primary treatment with curative intention [2]. Therefore, development of distant metastases is the most crucial and lethal event during the disease course, critically limiting therapy options. Since current clinical and histopathological classifications and molecular markers are not sufficient for prediction of metastasis, the development of biomarkers for the early and precise identification of patients at high-risk for metastasis at early stages of the disease is of utmost importance.

We identified the novel gene Metastasis Associated in Colon Cancer 1, MACC1, based on human colon cancer specimens [3]. In cell culture, MACC1 drives proliferation, migration, invasion, wound healing and dissemination and regulates genes transcriptionally important for metastasis, e.g. the receptor tyrosine kinase MET. It is crucially involved in fundamental biological processes, e.g. apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), via pathways such as the HGF/MET/MACC1 axis. In several xenograft mouse models, MACC1 induces tumor progression and metastasis [3,4].

In CRC patients, MACC1 is a tumor stage-independent predictor for metastasis and survival, and allows early identification of high-risk cases [4-6]. Importantly, MACC1 has also been identified as a valuable biomarker in carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract such as gastric [7], esophagus [8], pancreatic [9] and hepatobiliary [10-12] as well as in carcinomas of the lung [13-15], ovaries [16], breast [17,18], upper urothelial tract [19], nasopharynx [20], malignant glioma [21,22] and osteosarcomas [23]. Remarkably, MACC1 levels consistently correlated with tumor progression, development of metastasis and patient survival in this broad range of solid tumor types, making MACC1 a decisive driver for disease progression (reviewed in [24]). The predictive value of MACC1 for therapy response was demonstrated in rectal, pancreatic, and advanced hepatocellular cancer [24]. Thus, MACC1 might be employed as a routine biomarker for diagnosis, disease prognosis and prediction of therapy response in the clinic. Tissue- and blood-based diagnostic tests have already been performed in retrospective and prospective studies [24].

However, the expression pattern of MACC1 protein within heterogeneous tumors with respect to refinement of patient risk assessment has not been addressed. Aim of this study is therefore to evaluate the geographic expression pattern of MACC1 protein in the tumor center, the invasion front and in tumor buds of clinical CRC samples. In parallel, we determined mismatch repair (MMR)-status, BRAF/KRAS-mutations and CpG-island methylation to determine the impact of oncogenic driver mutations on MACC1 expression. Taken together, we report for the first time the differential expression of MACC1 in CRC with increasing levels from tumor center to invasion front. MACC1 expression at the invasion front was identified as the best predictor for aggressive clinicopathological features, tumor budding, metastasis formation and poor survival outcome.

Methods

Patients and study design

Two hundred and twenty unselected, non-consecutive CRC patients surgically treated from 2004–2007 at the Aretaieion University Hospital, University of Athens, Greece were included in this study [Figure 1]. Clinical information on patient gender, age at diagnosis, tumor diameter, tumor location, post-operative therapy and disease-specific survival time was obtained from patient records. An experienced gastrointestinal pathologist (EK) reviewed all histopathological slides according to the UICC TNM Classification 7th edition. Data on pathological T (pT), N (pN), and M-stage (pM), the presence of lymphatic invasion (L), venous invasion (V), perineural invasion (Pn), tumor grade (G), histological subtype and tumor growth pattern was recorded. Tumor budding was assessed using the 10 high-power fields (10HPF) method (40×; HPF field area 0.049 mm2) of highest density along the invasive front [25,26]. For each case, one full tissue section of invasive adenocarcinoma including the geographic areas tumor center, invasive front and tumor buds were selected for analysis of MACC1 expression by immunohistochemistry. Peritumoral normal mucosa was evaluated for MACC1 expression where available (n = 59). 33 cases were excluded based on insufficient material remaining on the tissue block. Final patient number was 187. Patient characteristics are found in [Table 1]. This study was designed in accordance with the reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) criteria [27].

Study design. 220 CRC patients with full clinicopathological features were entered into the study. Cases were analyzed for BRAF and KRAS mutations and MMR-protein expression was determined. Tumors of the CpG-Island methylator phenotype were identified using pyrosequencing. MACC1 protein expression in normal mucosa, tumor center, tumor front and tumor buds was evaluated by immunohistochemistry using full tissue sections. MACC1 expression in each geographic area of CRC was analyzed with clinicopathological features, patient survival and molecular features.

Ethics committee approval

The use of patient data has been approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Athens, Greece.

Tissue sections and MACC1 immunohistochemistry

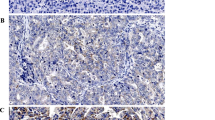

Full tissue sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded surgical resection specimens were cut at 4 μm. For immunohistochemistry of MACC1, sections were deparaffinized by successive immersions in xylene (20 minutes), acetone/Tris 2:1, acetone/Tris 1:2, Tris/NaCl, aqua dest (5 minutes each). Epitopes were demasked with 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6, microwave). After blocking (5% goat serum, 30 minutes), sections were incubated with the rabbit polyclonal anti-MACC1 antibody (1:100, Sigma HPA020103) for three hours at room temperature. Detection was performed using the biotin-based ABC kit (Dako; anti-rabbit biotin antibody and anti-biotin-streptavidin-HRP) and diaminobenzidine (1 minute) as substrate. Counter staining with Mayer’s haematoxylin was done for 2 minutes. Negative biological controls were performed using a matched multi-punch tissue microarray (TMA) of 50 CRC cases including normal mucosa [Figure 2A] and tumor tissue, negative technical controls were carried out by omitting the primary MACC1 antibody [Additional file 1: Figure S1].

MACC1 protein expression analysis in CRC. A: MACC1 expression in normal mucosa (1), tumor center (2), tumor front (3) and tumor buds (4; arrows) was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. B: Four representative cases of colorectal adenocarcinoma showing a significant increase of MACC1 expression from the tumor center towards the invasive front and MACC1 over-expressing tumor budding cells.

Evaluation of MACC1

We analyzed MACC1 expression in each geographic zone (normal mucosa, tumor center, invasive front) of whole tissue sections in analogy to the Rüschoff criteria for evaluation of Her2 biomarker expression [28]. Briefly, MACC1 expression was scored from 0 (absent staining) to 3 (strong staining). A score of 3 was assigned when a strong, unequivocally positive cytoplasmic and/or nuclear staining was observed at low magnification (5×) in a given geographic area. A score of 2 was assigned when higher magnification (10×) was needed to recognize MACC1 positivity. When high-power magnification (20×-40×) was required to recognize MACC1 positivity, a score of 1 was assigned. For tumor buds, the total number of buds was counted in one HPF of highest density at the invasive front and the number and proportion of buds showing MACC1 positivity was recorded.

KRAS, BRAF and MMR status

BRAF (exon 15, V600E mutations) and KRAS (exon 2, codon 12 and 13) mutations were analyzed using pyrosequencing as previously described [29]. For identification of tumors with high-level CpG island methylation (CpG island methylator phenotype, CIMP), PCR analysis of CpG-loci of six genes (SOCS1, NEUROG1, MLH1, CRABP1A, CDKN2A, RUNX3) was carried out by pyrosequencing as recently reported [29].

Mismatch-repair (MMR) protein expression was determined by immunohistochemistry for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 using a multi-punch tissue microarray containing an average of four tumor cores per case. Staining was carried out as previously described. MMR-protein expression was scored as positive when staining for all MMR-proteins was observed.

Statistical analysis

MACC1 positive cases were defined as MACC1 scores 1–3 by immunohistochemistry, negative cases were defined as score 0. Differences in MACC1 expression by geographic area and tissue type were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The correlation of MACC1 expression with clinicopathological and molecular features was evaluated using the Chi-Square, or Fisher’s Exact test as appropriate. Survival time analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and tested using the log-rank test in univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis for the prognostic effect of MACC1 expression at the tumor front and the potential confounders pT, pN, pM and adjuvant therapy was performed using a Cox regression model after verification of the proportional hazards assumption. Adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing was not undertaken [30]. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS (V9.2, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Geographic analysis of MACC1 expression

MACC1 was significantly over-expressed in tumor tissue as compared to normal mucosa (p < 0.001) [Figure 2A]. In tumor tissue, a gradient of MACC1 expression from the tumor center to the invasive front was identified (p = 0.0012) [Figure 2B]. In tumor buds, a strong cytoplasmic expression was observed: 55% of the dissociated single cells or small clusters of up to five cells identified at the invasive front demonstrated MACC1 expression [Figure 2B]. No MACC1 expression was observed in the tumor stroma.

MACC1 expression in the tumor center

In the tumor center, MACC1 expression (score 1–3) was observed in 58.3% of cases. Patients with strong MACC1 expression in the tumor center frequently presented with locally advanced pT3/4 tumors (p = 0.0288) as compared to MACC1 negative cases [Table 1]. In fact, 80% of MACC1 positive tumors showed infiltration into the pericolic fat or penetration of the serosa. MACC1 positivity in the tumor center further predicted aggressive tumor growth with presence of lymphatic invasion (p = 0.0373), venous invasion (p = 0.0352) and frequent metastasis to loco regional lymph nodes (p = 0.0018). Further, MACC1 expression in the tumor center was highly correlated with presence of high-grade tumor budding. However, no impact of MACC1 expression in the tumor center on the frequency of distant metastasis or patient survival was observed.

MACC1 expression at the invasive front

At the tumor front, MACC1 expression was observed in 72.2% of cases. MACC1 staining at the tumor front was seen in aggressive tumors with more advanced pT-stage (p = 0.0005), presence of lymphatic (p = 0.002) and venous (p = 0.0125) invasion as well as frequent nodal metastasis (p = 0.0001) [Table 2]. MACC1 expression at the tumor front was strongly predictive for the formation of distant metastasis (p = 0.0223). In fact, 18 of 19 patients with distant metastasis were correctly identified based on marker expression in this geographic area, indicating that MACC1 expression at the tumor host interface may be particularly important for tumor spread to distant organs. In consistence with this, strong MACC1 expression at the invasive front correlated with a high grade tumor budding phenotype (p = 0.0006). MACC1 positivity at the invasive front predicted poor overall survival outcome (p = 0.0217) in univariate analysis [Figure 3], however the prognostic impact of marker expression was not independent of T-stage, N-stage and adjuvant therapy as identified in multivariable analysis (p = 0.7827) [Table 3].

MACC1 expression in tumor buds

MACC1 expression was observed in 55% of tumor buds. In tumor buds, MACC1 expression correlated with aggressive disease biology. A higher proportion of MACC1 positive tumor buds was detected in patients with more advanced T-stage (p < 0.0001), higher overall TNM-stage (p = 0.0004) and presence of nodal metastasis (p = 0.0453) [Table 2]. No impact of MACC1 expression in tumor buds on survival was observed.

Geographic expression patterns of MACC1 in a molecular pathology context

KRAS mutations were identified in 32.6% of patients (n = 61) by pyrosequencing, while activating BRAF (V600) mutations were found in 8.5% of patients (n = 16). 8.5% of patients showed loss of MMR-protein expression by immunohistochemistry, while 7% (n = 13) of cases were classified as CIMP-high. No impact of molecular features on MACC1 protein expression was observed independent of the geographic area analyzed.

Discussion

In the current study we perform a geographic analysis of MACC1 expression in CRC with a particular focus on EMT-like cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment, also called tumor buds. As molecular features of CRC impact prognosis, we correlate MACC1 protein expression with MMR-status, BRAF- and KRAS-mutation as well as CpG-island methylation.

We demonstrate that MACC1 is variably expressed in normal mucosa, tumor center, invasive front and tumor buds. CRC is a highly heterogeneous disease characterized by marked genetic, spatial and temporal dynamics [31]. Tumor heterogeneity is present even in early invasive disease and may affect the reproducibility of biomarker assessment [32]. In a novel geographic approach towards immunohistochemical MACC1 expression analysis on full tissue sections, we identify a progressive increase of MACC1 positivity from the tumor center towards the invasive front with frequent overexpression in tumor budding cells. MACC1 gene function has been implicated in disease progression of CRC through activation of the MET- and beta-catenin (CTNNB1) pathways [3,33]. Activation of EMT in the process of invasion is a central step towards the seeding of metastasis [34-36]. Importantly, MACC1 overexpression at the invasive front was significantly associated with presence of distant metastasis and was a strong prognostic indicator. As death from CRC is predominantly determined by metastatic dissemination, the prognostic impact of MACC1 in this geographic area further corroborates the exceptional importance of the tumor microenvironment for determining prognosis [37].

Tumor budding is officially recognized by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) as an independent additional prognostic indicator in CRC [38]. A high grade tumor budding phenotype is consistently associated with aggressive clinicopathological features, lymph node and distant metastasis [36]. It is thought that tumor budding at the tumor invasive front is a histomorphological hallmark of EMT. Tumor buds overexpress protein markers associated with tumor cell migration and invasion such as matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2), MMP9 and cathepsinB (CTSB) [36]. Interestingly, MMP9 was previously described as being regulated by MACC1 in hepatocellular carcinoma and gastric cancer cell lines [39,40]. Further, activation of WNT-signaling and loss of E-Cadherin (CDH1) contributes to dissociative growth of tumor budding cells and loss of an epithelial phenotype. The expression of proteins such as Raf-kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) and neurotrophic tropomyosine kinase receptor type 2 (NTRK2) contribute to the resistance to apoptosis and anoikis [41,42]. Interestingly, MACC1 overexpression in any geographic region of CRC was significantly associated with high grade tumor budding at the invasive front and aggressive histopathological features including more advanced pT and pN-stages, venous and lymphatic invasion. In consistence with recently published literature, this suggests that active MET signaling contributes to dissociative tumor growth, tumor progression and invasion [43]. MACC1 overexpression in tumor budding cells themselves provides further evidence of their biological aggressiveness and likens these cells to EMT-like cancer cells [43]. As MACC1 has been suggested as a potential therapeutic target, overexpression on EMT-like cancer cells may represent an attractive option to manipulate cancer initiating cells at the tumor host interface in the process of invasion [44].

Biomarkers with predictive value for metastatic disease relapse have the potential to aid clinical management of CRC patients as additional prognostic indicators. The current approach towards active surveillance of CRC patients following resection is monitoring of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, but suffers from suboptimal sensitivity and specificity [45]. As metastatic relapse is a decisive event that determines prognosis of the CRC patient, early identification of high risk patients is an important goal for biomarker development. Several biomarkers have recently been highlighted to guide the identification of patients at risk of metastatic relapse. Examples include expression of RKIP in the primary tumor [41] and serum biomarkers such as microRNA-200c [46]. Based on the variety of detection methods, possibilities for assessment in tumor tissue and plasma and inclusion in early clinical trials, MACC1 is a promising candidate in the growing list of potentially valuable biomarkers to aid the identification of high risk CRC patients [6,24].

Molecular markers such as KRAS- and BRAF-mutations contribute predictive information for response to EGFR-inhibitors, but their value for identification of patients at high risk of metastatic relapse independent of disease stage is limited [47]. Interestingly, MACC1 expression was found to be independent of oncogenic driver mutations including activating KRAS-, BRAF- mutations, microsatellite instability and CIMP. This suggests that the association of MACC1 overexpression with presence of metastatic disease may be independent of the genetic features of CRC. MACC1 may therefore represent a complementary biomarker to KRAS- and BRAF- gene mutation status allowing the identification of patients at high risk of metastatic relapse. However, based on the relatively small number of cases identified with KRAS-, BRAF- mutations, CIMP or MMR-deficiency, this data cannot exclude an association between MACC1 and the molecular markers under study and requires independent validation.

This investigation has several strengths. The study is designed based on a hypothesis driven approach in full accordance with the REMARK guidelines for tumor marker prognostic studies [27]. Analyses are based on a very well characterized cohort of 187 CRC patients with full clinicopathological data, follow-up and therapy information. Marker analysis on full tissue sections accounts for tumor heterogeneity and allows expression analysis in tumor buds at the tumor-host interface. Weaknesses include the relatively small patient number included in the analysis of molecular pathology features with MACC1 expression. Further, marker cut-off levels may be influenced by the analysis methods and specific characteristics of the cohort under study. Consequently we recommend validation of the geographic expression pattern of MACC1 as a biomarker using independent patient cohorts.

Conclusions

This study further advances the development of MACC1 as a predictive biomarker. By geographic protein expression analysis, we illustrate that MACC1 is differentially expressed in normal mucosa, tumor center and at the invasive front of colorectal cancer. Marker positivity is frequently seen in tumor buds and identifies cancer cells with particularly aggressive behavior. At the invasive front, MACC1 expression best predicts aggressive clinicopathological features, tumor budding, and metastasis formation. MACC1 biomarker expression was not influenced by MMR-status, BRAF or KRAS-mutations or CpG-island methylation. Based on meaningful functional data and strong potential for translational application, MACC1 has to be classified as a promising biomarker for validation in prospective studies.

Abbreviations

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- CDH1:

-

E-Cadherin

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CTNNB1:

-

Beta-catenin

- CTSB:

-

CathepsinB

- CIMP:

-

CpG-island methylator phenotype

- HPF:

-

High-power field

- MACC1:

-

Metastasis associated in colon cancer 1

- MET:

-

MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase

- MMP:

-

Matrix metallopeptidase

- MMR:

-

Mismatch repair

- NTRK2:

-

Neurotrophic tropomyosine kinase receptor type 2

- REMARK:

-

Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies

- RKIP:

-

Raf kinase inhibitor protein

- TMA:

-

Tissue microarray

- UICC:

-

Union for International Cancer Control

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30.

Stein U, Schlag PM. Clinical, biological, and molecular aspects of metastasis in colorectal cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2007;176:61–80.

Stein U, Walther W, Arlt F, Schwabe H, Smith J, Fichtner I, et al. MACC1, a newly identified key regulator of HGF-MET signaling, predicts colon cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):59–67.

Pichorner A, Sack U, Kobelt D, Kelch I, Arlt F, Smith J, et al. In vivo imaging of colorectal cancer growth and metastasis by targeting MACC1 with shRNA in xenografted mice. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29(6):573–83.

Nitsche U, Rosenberg R, Balmert A, Schuster T, Slotta-Huspenina J, Herrmann P, et al. Integrative marker analysis allows risk assessment for metastasis in stage II colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;256(5):763–71. discussion 771.

Stein U, Burock S, Herrmann P, Wendler I, Niederstrasser M, Wernecke KD, et al. Circulating MACC1 transcripts in colorectal cancer patient plasma predict metastasis and prognosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49249.

Guo T, Yang J, Yao J, Zhang Y, Da M, Duan Y. Expression of MACC1 and c-Met in human gastric cancer and its clinical significance. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13(1):121.

Wang JJ, Hong Q, Hu CG, Fang YJ, Wang Y. [Significance of MACC1 protein expression in esophageal carcinoma]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2013;93(32):2584–6.

Wang G, Kang MX, Lu WJ, Chen Y, Zhang B, Wu YL. MACC1: A potential molecule associated with pancreatic cancer metastasis and chemoresistance. Oncol Lett. 2012;4(4):783–91.

Xie C, Wu J, Yun J, Lai J, Yuan Y, Gao Z, et al. MACC1 as a prognostic biomarker for early-stage and AFP-normal hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64235.

Gao S, Lin BY, Yang Z, Zheng ZY, Liu ZK, Wu LM, et al. Role of overexpression of MACC1 and/or FAK in predicting prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(3):268–75.

Ji D, Lu ZT, Li YQ, Liang ZY, Zhang PF, Li C, et al. MACC1 expression correlates with PFKFB2 and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(2):999–1003.

Chundong G, Uramoto H, Onitsuka T, Shimokawa H, Iwanami T, Nakagawa M, et al. Molecular diagnosis of MACC1 status in lung adenocarcinoma by immunohistochemical analysis. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(4):1141–5.

Shimokawa H, Uramoto H, Onitsuka T, Chundong G, Hanagiri T, Oyama T, et al. Overexpression of MACC1 mRNA in lung adenocarcinoma is associated with postoperative recurrence. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(4):895–8.

Wang Z, Li Z, Wu C, Wang Y, Xia Y, Chen L, et al. MACC1 overexpression predicts a poor prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(1):790.

Sheng XJ, Li Z, Sun M, Wang ZH, Zhou DM, Li JQ, et al. MACC1 induces metastasis in ovarian carcinoma by upregulating hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-MET. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(2):891–7.

Huang Y, Zhang H, Cai J, Fang L, Wu J, Ye C, et al. Overexpression of MACC1 and Its significance in human Breast Cancer Progression. Cell & Biosci. 2013;3(1):16.

Muendlein A, Hubalek M, Geller-Rhomberg S, Gasser K, Winder T, Drexel H, et al. Significant survival impact of MACC1 polymorphisms in HER2 positive breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(12):2134–41.

Hu H, Tian D, Chen T, Han R, Sun Y, Wu C. Metastasis-associated in colon cancer 1 is a novel survival-related biomarker for human patients with renal pelvis carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100161.

Meng F, Li H, Shi H, Yang Q, Zhang F, Yang Y, et al. MACC1 down-regulation inhibits proliferation and tumourigenicity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells through Akt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60821.

Yang T, Kong B, Kuang YQ, Cheng L, Gu JW, Zhang JH, et al. Overexpression of MACC1 protein and its clinical implications in patients with glioma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(1):815–9.

Hagemann C, Fuchs S, Monoranu CM, Herrmann P, Smith J, Hohmann T, et al. Impact of MACC1 on human malignant glioma progression and patients’ unfavorable prognosis. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(12):1696–709.

Zhang K, Zhang Y, Zhu H, Xue N, Liu J, Shan C, et al. High expression of MACC1 predicts poor prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(2):1343–50.

Stein U. MACC1 - a novel target for solid cancers. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17(9):1039–52.

Horcic M, Koelzer VH, Karamitopoulou E, Terracciano L, Puppa G, Zlobec I, et al. Tumor budding score based on 10 high-power fields is a promising basis for a standardized prognostic scoring system in stage II colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(5):697–705.

Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I, Kolzer V, Kondi-Pafiti A, Patsouris ES, Gennatas K, et al. Proposal for a 10-high-power-fields scoring method for the assessment of tumor budding in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(2):295–301.

Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. BMC Med. 2012;10:51.

Ruschoff J, Nagelmeier I, Baretton G, Dietel M, Hofler H, Schildhaus HU, et al. Her2 testing in gastric cancer. What is different in comparison to breast cancer? Pathologe. 2010;31(3):208–17.

Dawson H, Galvan JA, Helbling M, Muller DE, Karamitopoulou E, Koelzer VH, et al. Possible role of Cdx2 in the serrated pathway of colorectal cancer characterized by BRAF mutation, high-level CpG Island methylator phenotype and mismatch repair-deficiency. Int J Cancer J Int du Cancer. 2014;134(10):2342–51.

Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316(7139):1236–8.

Staub E, Groene J, Heinze M, Mennerich D, Roepcke S, Klaman I, et al. Genome-wide expression patterns of invasion front, inner tumor mass and surrounding normal epithelium of colorectal tumors. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:79.

Lips EH, van Eijk R, de Graaf EJ, Doornebosch PG, de Miranda NF, Oosting J, et al. Progression and tumor heterogeneity analysis in early rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(3):772–81.

Zhen T, Dai S, Li H, Yang Y, Kang L, Shi H, et al. MACC1 promotes carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer via beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2014;5(11):3756–69.

Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Kunz-Schughart LA, et al. Variable beta-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10356–61.

Brabletz T, Hlubek F, Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Hiendlmeyer E, Jung A, et al. Invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer: epithelial-mesenchymal transition, mesenchymal-epithelial transition, stem cells and beta-catenin. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179(1–2):56–65.

Zlobec I, Lugli A. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and tumor budding in aggressive colorectal cancer: tumor budding as oncotarget. Oncotarget. 2010;1(7):651–61.

Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature. 2006;441(7092):444–50.

Bosman FT. World Health Organization., International Agency for Research on Cancer.: WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system, 4th edn. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

Gao J, Ding F, Liu Q, Yao Y. Knockdown of MACC1 expression suppressed hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion and inhibited expression of MMP2 and MMP9. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;376(1–2):21–32.

Wang L, Wu Y, Lin L, Liu P, Huang H, Liao W, et al. Metastasis-associated in colon cancer-1 upregulation predicts a poor prognosis of gastric cancer, and promotes tumor cell proliferation and invasion. Int J Cancer J Int du Cancer. 2013;133(6):1419–30.

Koelzer VH, Karamitopoulou E, Dawson H, Kondi-Pafiti A, Zlobec I, Lugli A. Geographic analysis of RKIP expression and its clinical relevance in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2088–96.

Dawson H, Koelzer VH, Karamitopoulou E, Economou M, Hammer C, Muller DE, et al. The apoptotic and proliferation rate of tumour budding cells in colorectal cancer outlines a heterogeneous population of cells with various impacts on clinical outcome. Histopathology. 2014;64(4):577–84.

Luraghi P, Reato G, Cipriano E, Sassi F, Orzan F, Bigatto V, et al. MET signaling in colon cancer stem-like cells blunts the therapeutic response to EGFR inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2014;74(6):1857–69.

Mathias RA, Gopal SK, Simpson RJ. Contribution of cells undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition to the tumour microenvironment. J Proteomics. 2013;78:545–57.

Kin C, Kidess E, Poultsides GA, Visser BC, Jeffrey SS. Colorectal cancer diagnostics: biomarkers, cell-free DNA, circulating tumor cells and defining heterogeneous populations by single-cell analysis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2013;13(6):581–99.

Toiyama Y, Hur K, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M, Boland CR, et al. Serum miR-200c is a novel prognostic and metastasis-predictive biomarker in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):735–43.

De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):753–62.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank José Galvan, Dominique Müller and Caroline Hammer from the Translational Research Unit, Institute of Pathology, University of Bern for excellent technical support.

Funding source

This project was funded by the German Cancer Consortium DKTK (US) and the Bernese Cancer League (IZ). The funding source had no influence on the study design, analyses or interpretation of the results presented in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Authors’ contributions

PH performed immunohistochemistry; VHK scored immunohistochemistry, reviewed cases, performed data interpretation and drafted the manuscript; US drafted the manuscript and together with AL conceived the study and study design, reviewed and approved the final manuscript; IZ performed data interpretation and statistical analysis, reviewed and approved the final manuscript. EK obtained, reviewed and categorized patient material and clinical data, reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Technical controls. No immune reactivity was observed in technical controls of normal mucosa (A), tumor center (B), tumor front (C) and tumor buds (D; arrows).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Koelzer, V.H., Herrmann, P., Zlobec, I. et al. Heterogeneity analysis of Metastasis Associated in Colon Cancer 1 (MACC1) for survival prognosis of colorectal cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 15, 160 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1150-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1150-z