Abstract

Background

The underlying pathophysiology of BA distribution is unclear and intriguing. Using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (HR-MRI), we sought to explore the plaque distribution of low-grade basilar artery (BA) atherosclerosis and its clinical relevance.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the imaging and clinical data of 61 patients with low-grade atherosclerotic BA stenosis (<50%). On HR-MRI, the plaques were categorized based on the involvement of the ventral, dorsal, or lateral sides of BA wall. A culprit plaque was defined if it was on the same slice or neighboring slices of symptomatic pontine infarcts and played a probable causal role (dorsal plaques with median pontine infarcts or lateral plaques with ipsilateral pontine infarcts). The relationships between plaque distribution and clinical presentations were analyzed.

Results

Twenty-five symptomatic and thirty-six asymptomatic BAs with 752 HR-MRI image slices were studied. The average length of BA atherosclerosis plaques was 12.16 ± 5.61mm (10.30 ± 6.44mm in symptomatic and 13.46 ± 7.03mm in asymptomatic patients, p = 0.079). The plaque distribution was similar at ventral (29.0%), dorsal (37.6%) and lateral walls (33.1%). The BA plaques in symptomatic patients were more frequently located at the dorsal (42.5%) and lateral (41.2%) walls than at the ventral walls (16.1%; P < 0.05). Compared with symptomatic patients, asymptomatic patients more likely had their plaques distributed at the ventral walls (P = 0.022). Culprit plaques were observed in 85.0% (17/20) pontine infarcts in symptomatic patients and only 14.3% (2/14) silent pontine infarcts in asymptomatic patients (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Low-grade BA atherosclerosis has a long distribution and evenly involves ventral, dorsal and lateral walls. The plaques at dorsal and lateral walls are associated with symptomatic pontine infarcts but not with silent infarcts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Emerging evidence has suggested the distribution of atherosclerotic plaque plays an important role in the occurrence of ischemic events [1]. In coronary artery and middle cerebral artery atherosclerosis, plaques naturally tend to form at the positions opposite to the orifices of branch or penetrating arteries [2, 3]. Once the plaques locate near the perforating orifices, they are more likely symptomatic and related to “snow plowing” effect during stenting process [3].

Basilar artery (BA) is the largest artery in the posterior circulation and forms the central core of this vascular territory. It gives rise to many side branches which can be divided into three groups: the cerebellar arteries, cerebral hemisphere branches and the perforating arteries [4]. The dorsal and lateral surfaces of the BA are a rich source of perforating arteries, while nearly no perforating arteries arise from the ventral surfaces of the BA [5]. To provide deep insight of the pathophysiology of BA atherosclerosis, in this study, we systematically described and compared the plaque distributions of symptomatic and asymptomatic low-grade BA atherosclerosis and clarify their clinical relevance.

Methods

Patients

This observational study was approved by the ethics committee at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, General Hospital of Chinese People’s Armed Police Forces, and Zhejiang University 2nd affiliate hospital. We retrospectively reviewed the high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (HR-MRI) databases (2006 to 2013) from three medical centers in China. All patients with BA atherosclerotic plaque on HR-MRI were enrolled if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) low-grade BA atherosclerotic stenosis (<50%) were detected by magnetic resonance angiography; (2) one or more atherosclerotic risk factors including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and cigarette smoking; (3) image quality good enough for analysis. Patients with the following conditions were excluded by clinical presentations, lab work and imaging:(1) arteritis; (2) dissection; (3) evidence of cardioembolism; and (4) co-existent vertebral artery atherosclerotic stenosis (≥50%).

Symptomatic patients were defined if there was an ischemic stroke in the distribution of BA within the proceeding four weeks, and new ischemic lesions were identified on diffusion-weighted and T2 weighted images. Asymptomatic patients were defined if there was no history of cerebrovascular events in the distribution of BA. Silent infarcts were defined if brain stem lesions were incidentally identified by MRI in clinical stroke-free subjects.

Imaging protocol

A 3.0 T GE scanner (Twinspeed; GE Medical Systems) with an 8-channel head coil was used. Conventional 3 dimensional time-of-flight (3D TOF) magnetic resonance angiography was obtained in an axial plane with the following parameters: repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 25.0/3.1ms; flip angle = 20°; field of view(FOV) = 240mm × 240mm; matrix size = 384 × 224; slice thickness = 1.4 mm, without slice gap; 1 signal averages. To examine the BA wall, HR-MRI sequences including T2 weighted imaging (T2WI), T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) and proton density weighted imaging (PDWI) were performed. Eight to fourteen slices, depending on the length of BA, were acquired along the short axis of the BA using the double-oblique plane with the following parameters: T2WI (TR/TE = 3360/45.3ms; FOV = 130mm × 130mm; matrix size = 384 × 384; slice thickness = 2mm; slice gap = 0.5mm; scan times = 2min10s), T1WI (TR/TE = 840/11.4ms; FOV = 130mm × 130mm; matrix size = 384 × 384; slice thickness = 2mm; slice gap = 0.5mm; scan times = 1min38s), PDWI (TR/TE = 2440/19.7ms; FOV = 130mm × 130mm; matrix size = 384 × 384; slice thickness = 2mm; slice gap = 0.5mm; scan times = 2min53s); 4 signal averages. Voxelsize was 0.33 × 0.33 × 2 mm. No smoothing filter was applied.

Image analysis

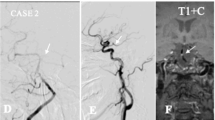

A plaque was identified if there was eccentric wall thickening, whereas the thinnest part was estimated to be <50% of the thickest point by visual inspection [6]. All cross-sections with eccentric plaque were classified based on their plaque orientation being centered on the ventral, dorsal, and lateral (left or right) sides of the vessel (Fig. 1). Each cross-section was grouped into 1 of the 4 quadrants. In cases when the plaque was distributed more than 1 quadrant, the quadrant with the maximal plaque thickness was chosen [2]. For each patient, we calculated the total length of BA atherosclerosis plaques (plaque length = plaque slices × slice thickness + slices gaps). A culprit plaque was defined if it fulfilled the following criteria: 1, an infarct occurred in the pon (Fig. 2); 2, the BA plaque can be seen on the same slice of the infarct or on the adjacent upper or lower slice; 3, there was a probable casual relationship between the plaque and the infarct (dorsal wall plaque with median pontine infarcts or lateral wall plaque for lateral pontine infarcts). All images were reviewed by two experienced readers blinded to clinical data, who used the software of the syngofast View-Viewer for DICOM images (Ver.1.0.0.34). The differences between the two observers were solved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SD and qualitative data are expressed as percentage. The continuous variables between the two groups were compared by the independent samples t-test. Categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. For each stenosis, the percentage of individual plaque distribution was calculated (Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1). The mean ventral, dorsal, lateral (left and right) plaque orientation of the total group was derived from the individual percentage distribution [3]. The comparison of the plaque distribution among different walls was performed by a Kruskal-Wallis test of the mean percentage of the distribution for each individual stenosis followed by Variance analysis and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Data comparisons between symptomatic and asymptomatic vessels were conducted with the Wilcoxon test. A probability value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Seventy and four patients with BA plaque were considered for enrollment. Five patients with poor image qualities and eight patients with vertebral artery stenosis (≥50%) were excluded. Sixty-one patients were finally included for analysis. Twenty-five patients were symptomatic and thirty-six patients asymptomatic. Of the symptomatic patients, 18 had pontine infarcts, 2 had infarcts involving both pontine and extra-pontine area (1 with thalamus infarct and 1 with cerebellum infarct), and 5 with extra-pontine infarcts (1 with cerebellum infarct, 1 with occipital lobe infarct, and 3 with thalamic infarct). Of the asymptomatic patients, 14 had silent pontine infarcts. Table 1 summarizes the demographic data, showing no difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic patient groups.

A total of 752 HR-MRI image slices were reviewed. Plaques were identified in 305 slices. Plaque distribution was found to be eccentric in 299 (98.0%) and concentric in 6 (1.97%) cross sections. Only seven patients (11.5%) had a one-slice plaque, while most BA plaque involved multiple slices on HR-MRI. The average length of BA atherosclerosis plaques was 12.16 ± 5.61mm (10.30 ± 6.44mm in symptomatic and 13.46 ± 7.03mm in asymptomatic patients, p = 0.079).

The plaques distributed at 1 quadrant of BA wall on 271 (88.9%) image slices, 2 quadrants on 18 (5.9%) slices, 3 quadrants on 10 (3.3%) slices, and 4 quadrants on 6 (1.97%) slices. Thirty -nine patients only with 1 quadrant of BA plaque were found, 16 patients with 2 quadrants, 7 patients with 3 quadrants, 4 patients with 4 quadrants. The percentage of plaque distribution was similar in ventral (29.0%), dorsal (37.6%) and lateral walls (33.1%; P > 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test). However, in symptomatic group, plaques were more frequently located at the dorsal (42.5%) and lateral (41.2%) walls than at the ventral walls (16.1%; P < 0.05, Variance analysis and Bonferroni correction test; Table 2). Compared with symptomatic patients, asymptomatic patients more likely had their plaques distributed at the ventral walls (P = 0.022). Symptomatic patients with pontine infarcts had more “culprit plaques” (17/20, 85.0%) than the patients with silent pontine infarcts (2/14, 14.3%; p = 0.000, Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, it was observed low-grade BA plaques had a long distribution and evenly involved ventral, dorsal and lateral walls. They did not follow the rule of coronary artery and middle cerebral artery atheroscleros is that plaques tend to locate at the opposite side of the orifices of penetrating arteries. However, BA plaques in symptomatic patients predominantly distributed in the dorsal and lateral walls. Comparatively, BA plaques in asymptomatic patientsmore likely located at ventral walls. Interestingly, it was also observed that the culprit plaques were only associate with symptomatic infarcts, not with silent infarcts. These results suggest the plaque distribution of BA atherosclerosis has unique characteristics and is closely relevant with ischemic events.

There have been several HR-MRI studies focusing on symptomatic BA atherosclerosis [7–11]. Klein et al. enrolled 41 patients with pontine infarct. More than 70% patients had a BA plaque detected on HR-MRI, including a high proportion of patients with normal basilar angiograms. The authors hypothesized BA plaques might protrude into the orifice of the perforators and cause the infarcts [7]. In another study, 38 symptomatic patients with at least 30% stenosis were recruited [8]. The plaque distribution on the narrowest lumen slice was evaluated. The authors reported the ventral wall was more likely involved. The current study has several strengths. First, the whole plaque distribution of BA was evaluated and the culprit plaques were further defined based on vascular anatomy. Second, both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were included, which make it possible to perform a comparative analysis. Third, only the patients with low grade BA stenosis and without vertebral artery stenosis were enrolled, that make the mechanism of embolism less likely account for the pontine infarcts.

The underlying pathophysiology of BA distribution is intriguing. Pathologic studies have shown that early atherosclerotic plaques appear to develop at the sites with the low or oscillatory wall shear stress [12]. Such sites commonly locate at the outer wall of a bifurcation, the inner wall of a curved artery, and the apex of a confluence. The blood flow of BA comes from two vertebral arteries and enters posterior cerebral arteries, with many penetrating arteries arise from its dorsal and lateral wall. Given the more widely and complicated microanatomy of BA than coronary artery and middle cerebral artery, it is difficult to identify the low sheer stress zones by simply following the rules established in coronary artery atherosclerosis. Further computerized hemodynamic studies on BA are warranted.

The results of our study are clinically meaningful. First, about two-thirds of BA plaques locate at ventral and dorsal walls, nearby the penetrating artery orifices, suggesting BA atherosclerosis has a high risk of developing penetrating infarcts. It may partly explain why intracranial stenting therapy has more snow-plowing complications in patients with BA atherosclerosis than the patients with middle cerebral artery atherosclersosis [3, 13, 14]. The close association between culprit plaques and symptomatic pontine infarcts suggest the knowledge of BA plaque distribution may potentially help us to estimate the likelihood of occlusion of the penetrating arteries and reduce the complication risk during stenting. Second, the underlying mechanisms of brain stem silent infarcts have been less well studied. Potential etiologies were presumed to be BA atherosclerosis or small vessel disease [11]. The high prevalence of non-culprit plaques in patients with silent pontine infarcts in our study doesn’t support the parent artery plaque as the causes. These plaques are more likely innocent bystander although they can be a potential marker for unhealthy vessel tree conditions.

Our study suffered from several limitations. First, the pathophysiology difference between low-grade and advanced BA stenosis has been not well studied. In current study, a proportion (7/25) of extra-pontine ischemic lesions were observed in symptomatic patients, suggesting the mechanisms of embolism may also involve. The interpretations of our data should be cautious and may not be applicable in advanced BA atherosclerosis. Second, we can not entirely exclude the possibility that the acute cerebral infarcts were caused by the branches or penetrating arteries lesions in our patients. Third, the retrospective design and the small sample size might lead to selective bias and thus limited its reliability.

Conclusion

In this study, we described the plaque distribution of low-grade BA plaque and reported its clinical relevance. Further prospective studies are required to investigate whether our findings are helpful in stratifying stroke risk in patients with BA atherosclerotic disease.

Abbreviations

- 3D TOF:

-

3Dimensional Time-of-flight

- BA:

-

Basilar artery

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- HR-MRI:

-

High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging

- PDWI:

-

Proton density weighted imaging

- T1WI:

-

T1 weighted imaging

- T2WI:

-

T2 weighted imaging

References

Ryu CW, Kwak HS, Jahng GH, Lee HN. High-resolution MRI of intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Neurointervention. 2014;9:9–20.

Watanabe H, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, Hozumi T, Yoshikawa J. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of plaque distribution in the ostium of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:827–9.

Xu WH, Li ML, Gao S, Ni J, Zhou LX, Yao M, et al. Plaque distribution of stenotic middle cerebral artery and its clinical relevance. Stroke. 2011;42:2957–9.

Marinković SV, Gibo H. The surgical anatomy of the perforating branches of the basilar artery. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:80–7.

Saeki N, Rhoton Jr AL. Microsurgical anatomy of the upper basilar artery and the posterior circle of Willis. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:563–78.

Xu WH, Li ML, Gao S, Ni J, Zhou LX, Yao M, et al. In vivo high-resolution MR imaging of symptomatic and asymptomatic middle cerebral artery atherosclerotic stenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:507–11.

Klein IF, Lavallée PC, Mazighi M, Schouman-Claeys E, Labreuche J, Amarenco P. Basilar artery atherosclerotic plaques in paramedian and lacunar pontine infarctions: a high-resolution MRI study. Stroke. 2010;41:1405–9.

Huang B, Yang WQ, Liu XT, Liu HJ, Li PJ, Lu HK. Basilar artery atherosclerotic plaques distribution in symptomatic patients: a 3.0T high-resolution MRI study. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:199–203.

Lou X, Ma N, Ma L, Jiang WJ. Contrast-enhanced 3T high-resolution MR imaging in symptomatic atherosclerotic basilar artery stenosis. A JNR Am Neuroradiol. 2013;34:513–7.

Ma N, Jiang WJ, Lou X, Ma L, Du B, Cai JF, et al. Arterial remodeling of advanced basilar atherosclerosis: a 3-tesla MRI study. Neurology. 2010;75:253–8.

Feng C, Xu Y, Bai X, Hua T, Li Q, Tang GY, et al. Basilar artery atherosclerosis and hypertensive small vessel disease in isolated pontine infarctions: a study based on high-resolution MRI. Eur Neurol. 2013;70:16–21.

Asakura T, Karino T. Flow patterns and spatial distribution of atherosclerotic lesions in humancoronaryarteries. Circ Res. 1990;66:1045–66.

Jiang WJ, Srivastava T, Gao F, Du B, Dong KH, Xu XT. Perforator stroke after elective stenting of symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Neurology. 2006;66:1868–72.

Leung TW, Yu SC, Lam WW, Chan AY, Lau AY, Wong LK. Would self-expanding stent occlude middle cerebral artery perforators? Stroke. 2009;40:1910–2.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is supported by Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University of China (NCET-12-0069), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471207, 81671370) and the Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2014-4-4015).

Authors’ contributions

W-HX was responsible for designing the study, analyzing the data and revising the manuscript. JY was responsible for collecting and analyzing the data, and drafting the manuscript. M-LL, Y-YX, ML, S-WW and X-TM were responsible for data collection. FF and SG were responsible for the study supervision and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This observational study was approved by the ethics committee at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, General Hospital of Chinese People’s Armed Police Forces, and Zhejiang University 2nd affiliate hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Percentage of individual plaque distribution. Calculations of the percentage of individual plaque distribution: The quadrant grouping slice is patient specific. For each stenosis, the percentage of individual plaque distribution was calculated. If a stenosis only had one slice with ventral plaque, for example, the percentage of its individual plaque distribution is ventral 100%, dorsal 0%, latera l0%. If the stenosis have 3 slices (ventral 2, dorsal 1), the percentage is ventral 66%, dorsal 33%, lateral 0% (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Li, ML., Xu, YY. et al. Plaque distribution of low-grade basilar artery atherosclerosis and its clinical relevance. BMC Neurol 17, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0785-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0785-y