Abstract

Background

Patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD), including stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD), are at high risk for stroke-related morbidity, mortality and bleeding. The overall risk/benefit balance of warfarin treatment among patients with ESRD and AF remains unclear.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the associations of warfarin use and stroke outcome, bleeding outcome or mortality in patients with ESRD and AF. We conducted a comprehensive literature search in Feb 2016 using key words related to ESRD, AF and warfarin in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library without language restriction. We searched for randomized trials and observational studies that compared the use of warfarin with no treatment, aspirin or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), and reported quantitative risk estimates on these outcomes. Paired reviewers screened articles, collected data and performed qualitative assessment using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-randomized Studies of Interventions. We conducted meta-analyses using the random-effects model with the DerSimonian - Laird estimator and the Knapp-Hartung methods as appropriate.

Results

We identified 2709 references and included 20 observational cohort studies that examined stroke outcome, bleeding outcome and mortality associated with warfarin use in 56,146 patients with ESRD and AF. The pooled estimates from meta-analysis for the stroke outcome suggested that warfarin use was not associated with all-cause stroke (HR = 0.92, 95 % CI 0.74–1.16) or any stroke (HR = 1.01, 95 % CI 0.81–1.26), or ischemic stroke (HR = 0.80, 95 % CI 0.58–1.11) among patients with ESRD and AF. In contrast, warfarin use was associated with significantly increased risk of all-cause bleeding (HR = 1.21, 95 % CI 1.01–1.44), but not associated with major bleeding (HR = 1.18, 95 % CI 0.82–1.69) or gastrointestinal bleeding (HR = 1.19, 95 % CI 0.81–1.76) or any bleeding (HR = 1.21, 95 % CI 0.99–1.48). There was insufficient evidence to evaluate the association between warfarin use and mortality in this population (pooled risk estimate not calculated due to high heterogeneity). Results on DOACs were inconclusive due to limited relevant studies.

Conclusions

Given the absence of efficacy and an increased bleeding risk, these findings call into question the use of warfarin for AF treatment among patients with ESRD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in adults with end stage renal disease (ESRD) is 11.6 % [1], about 11-times higher than the prevalence of AF in the general adult population [2]. Among patients with ESRD and AF, the incidence of stroke is 5.2 per 100 person-years and the incidence of mortality is 26.9 per 100 person-years. These incidences are notably higher than the incidence of stroke (1.9 per 100 person-years) and the incidence of mortality (13.4 per 100 person-years) in patients with ESRD who do not have AF [1].

Anticoagulation therapy, such as warfarin, is commonly prescribed to prevent ischemic stroke and its efficacy is well demonstrated in a meta-analysis of randomized trials and observational studies in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and AF [3]. Another meta-analysis suggested that using warfarin does not significantly increase adverse bleeding outcomes among patients with AF and mild to moderate CKD [4]. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) including dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban are available as alternatives to warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke and systemic thromboembolism in patients with AF without renal impairment. Some data on DOACs suggested a higher efficacy [3] and lower bleeding risk [4] of these agents compared with warfarin in patients with CKD and AF. However, the product labels stated that the use of dabigatran and rivaroxaban should be avoided in patients with severe renal impairment (i.e. creatinine clearance [CrCl] < 30 mL/min). Previous randomized controlled trials have excluded patients with advanced CKD on dialysis and thus there remains a lack of evidence to support the use of warfarin or DOACs in this population. Despite the wealth of evidence of anticoagulation therapy in patients with CKD, the benefits and risks of warfarin and DOACs in patients with ESRD and AF are unclear.

The guidelines for warfarin treatment in patients with ESRD and AF are not uniform. The current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) guideline recommends warfarin for oral anticoagulation in patients with ESRD and nonvalvular AF who have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or greater [5]. The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline suggests that routine anticoagulation in patients with ESRD and AF for primary prevention of stroke is not indicated because of increased risk for bleeding and lack of systematic evidence for stroke prevention benefit, whereas recommendations for secondary prevention and careful monitoring of all patients receiving dialysis anticoagulation remain valid [6]. Recently published systematic reviews which examined the benefit and risk of warfarin in patients with ESRD and AF were limited to patients on hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) [7, 8], or used an inappropriate measure of association (risk ratio [RR] instead of hazard ratio [HR]) [9]. Because the risk of outcomes may not remain constant over the study period and loss to follow up are common in observational studies, HR is more appropriate for evaluating the effects of warfarin as most observational studies report time-to-event data. Moreover, these studies reported conflicting results regarding the association between warfarin use and stroke outcome: one review reported warfarin use was associated with higher risk of any stroke (RR 1.50, 95 % CI: 1.13–1.99) [9] while other reviews reported a lack of association between warfarin use and stroke [7, 8, 10].

Therefore, we expanded the population to stage 5 CKD, HD, and PD and conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses on the benefits and risks of warfarin use. We used appropriate analytic tools such as the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-randomized Studies of Interventions [11] for qualitative assessment and the Knapp-Hartung methods [12] for quantitative assessment. The objective of this study was to review and summarize the associations between warfarin use and stroke outcomes, bleeding outcomes and all-cause mortality, as compared to no warfarin use, aspirin or DOACs, among patients with ESRD and AF.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed the systematic review and meta-analysis in adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. First, we searched PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Central register using synonyms and variations of the following search terms without language or date restrictions: “end stage renal disease”, and “atrial fibrillation” and “anticoagulants or warfarin”. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g. MeSH and Emtree), free-text words (i.e. words appearing in the title, abstract or keywords of a database entry), and truncated terms as appropriate for each database (Appendix). All databases were searched from their start date to February 10, 2016. In addition to the electronic database searches, we hand-searched the reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Study selection

We searched for published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods), and observational studies which examined the benefits and risks of warfarin in patients with ESRD and AF. We included studies of at least 10 patients with ESRD (HD, PD, stage 5 CKD i.e. GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) and with pre-existing or newly diagnosed AF (all types). We also included studies with broader study populations (i.e. CKD) if they reported outcomes separately for participants with ESRD. We included studies which compared warfarin use with placebo, no treatment or other antithrombotic agents (e.g. aspirin, dabigatran, rivaroxban, apixaban). Studies needed to report quantitative data on the risk for any of the following outcomes: all-cause stroke (any stroke i.e. including ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, systematic thromboembolism and transient ischemic attacks; ischemic stroke), all-cause bleeding (any bleeding, major bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding) or all-cause mortality. We only reviewed full articles because conference abstracts would not provide the details necessary for qualitative and quantitative assessments.

Data collection

Two reviewer authors (JT, SL) independently conducted abstract screening and selected relevant studies for data abstraction according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria above. We used a web-based systematic review software DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada) to document the article screening process and to develop standardized data collection forms. For each study, we abstracted bibliographic information (first author, publication year); general information (location of study, sample size, number of treatment groups, number of participants); participant characteristics (age, gender, history of stroke and bleeding); interventions (treatment groups); outcomes (definition, analytic method, crude event data, adjusted risk estimates (HR) and their 95 % CIs); and study quality. We also contacted the corresponding authors of four included studies [13–16] to obtain missing outcome data. We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI) [11] to assess the risk of bias because it was designed specifically for non-randomized studies that evaluate effectiveness of interventions. We rated the risk of bias on seven domains at the study level, and rated the overall risk of bias based on the domain with the highest risk of bias. Discrepancies in study selection and data collection were resolved by the two reviewers through discussions and consensus.

Data analysis

We assessed the clinical and methodologic heterogeneity in participant characteristics (i.e. ESRD status, age, gender, comorbidities, prevalent vs. incident warfarin users) and assessments of outcomes (i.e. outcome definitions and analytic methods). We used the Cochran Q test, which follows a Chi-square distribution with n-1 of freedom, with an alpha of < 0.10 to assess the presence of statistical heterogeneity between studies. We also calculated the I2 statistic, which ranges between 0 and 100 %, to determine the proportion of between group variability that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance [17]. If there was evidence for considerable heterogeneity (i.e. I2 ≥ 80 %), we displayed the risk estimates in a forest plot but did not calculate the overall risk estimates. Otherwise, we conducted meta-analyses using the random effects model with the DerSimonian-Laird estimator [18] and the Knapp-Hartung approach [12], where appropriate, using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed pre-specified sensitivity analyses where studies with prevalent warfarin users and studies with low methodological quality were excluded from meta-analyses. We assessed the presence of publication bias using funnel plots with the natural log of HR plotted on the y-axis and the standard error of natural log of HR plotted on the x-axis. We also tested the presence of small-study effects using the Egger’s test [19]. We conducted meta-regressions with the Knapp-Hartung approach to evaluate the impact of study quality (moderate/high risk of bias vs critical risk of bias), patient population (HD only vs mixed ESRD population), and study design (studies including incident warfarin users only vs. studies including prevalent and incident warfarin users) on stroke outcome, bleeding outcome or mortality.

Results

Description of included studies

We identified 2709 references from the electronic database search; no additional references were identified from hand searching. After removing 593 duplicate references and excluding 2022 references in titles and abstracts screening, we did a full-text review of 94 references. After excluding another 74 references, we included 20 articles for qualitative and quantitative assessment (Fig. 1).

All 20 investigations were observational cohort studies examining the outcomes of warfarin use in patients with ESRD and AF. Nineteen studies compared warfarin use to no warfarin use, while two studies also compared warfarin use to aspirin [20, 21] and one study compared warfarin use to dabigatran and rivaroxaban [20]. A total of 56,146 patients with ESRD and AF, including 34,840 on HD, 315 on PD, 610 with stage 5 CKD, and 20,381 mixed ESRD population, were included in these studies. These studies included a median of 690 (interquartile range [IQR] 204–3012) patients with ESRD and AF, and had a median duration of 7.0 (IQR 2.9–9.4) years. Eight studies were based on administrative claims or national/regional registry data [13, 22–28], and they generally were longer and larger studies. Twenty studies included participants with a mean age above 60 years old, including two studies that were limited to older adults above 65 years old [22, 27]. Nine studies examined effects of warfarin use between incident warfarin users and nonusers [20, 22–29], whereas the other 11 studies compared prevalent warfarin users with nonusers (Table 1, Appendix Table 3).

Risk of bias assessment

Due to the observational nature of cohort studies, all 20 included studies had at least an overall rating of moderate risk of bias: 5 studies were rated as moderate [22, 25–28]; 7 studies were rated as serious [13, 14, 20, 23, 24, 30, 31]; 8 studies were rated as having a critical risk of bias [14–16, 21, 29, 32–35] (Table 2, Appendix Table 4).

Association of warfarin with stroke, bleeding and mortality

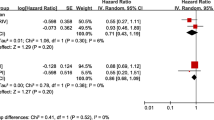

The meta-analyses of warfarin use included 15 studies that examined all-cause stroke (I2 68.1 %), 11 studies that examined all-cause bleeding (I2 48.3 %), and 12 studies that examined all-cause mortality (I2 85.7 %) and reported HRs as outcome measures (Fig. 2a-c). Warfarin use was not statistically associated with reduction in all-cause stroke (HR 0.92, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.74–1.16) (Fig. 2a), and was not associated with any stroke (HR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.81–1.26) or ischemic stroke (HR 0.80, 95 % CI 0.58–1.11).

a Meta-analysis of stroke outcome in patients with end stage renal disease and atrial fibrillation by warfarin use. b Meta-analysis of bleeding outcome in patients with end stage renal disease and atrial fibrillation by warfarin use. c Forest plot of mortality in patients with end stage renal disease and atrial fibrillation by warfarin use

By contrast, there was a positive and statistically significant association between warfarin use and all-cause bleeding (HR 1.21, 95 % CI 1.01–1.44) (Fig. 2b). Warfarin use was not associated with major bleeding (HR 1.18, 95 % CI 0.82–1.69) or gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 1.19, 95 % CI 0.81–1.76). While there was a trend towards increased risk of any bleeding, the association was not significant (HR 1.21, 95 % CI 0.99–1.48).

Finally, there was high statistical heterogeneity among the 12 studies (I2 = 85.7 %) that examined all-cause mortality, and thus we did not calculate an overall risk estimate (Fig. 2c). Most studies showed non-significant results except for 4 studies that found lower risk of mortality associated warfarin use [13, 16, 24, 34].

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis in which we excluded 11 studies with prevalent warfarin users, the overall risk estimates were 0.88 (95 % CI 0.65–1.18) for all-cause stroke, 1.14 (95 % CI 0.88–1.47) for all-cause bleeding, and 0.99 (95 % CI 0.83–1.17) for mortality respectively (Appendix Figure 4a–c). In the analysis which we included only studies with prevalent users, the results were consistent with the aforementioned sensitivity analysis: the overall risk estimates were 0.99 (95 % CI 0.69–1.42) for all-cause stroke, 1.31 (95 % CI 0.91–1.87) for all-cause bleeding, 0.72 (HR 0.47–1.11) for all-cause mortality. In the sensitivity analysis in which we excluded studies with critical risk of bias and low methodological quality (Appendix Figure 5a–c), the results were not statistically significant (all-cause stroke: HR 0.91, 95 % CI 0.73–1.14; all-cause bleeding: HR 1.13, 95 % CI 0.99–1.28; pooled risk estimate for mortality not calculated due to heterogeneity).

In the meta-regression, we did not find significant impact of study characteristics on outcomes except for study population in the analysis of all-cause stroke outcome. Compared to studies that included mixed ESRD population, studies including only patients on HD reported higher association with all-cause stroke outcome (OR 5.83, 95 % CI 1.22–27.98; P = 0.03). In the funnel plots, we did not observe obvious asymmetry in the funnel plots for all three outcomes (Fig. 3a–c). Statistical tests for small-study effects were not statistically significant for the three outcomes (P = 0.21, 0.51 and 0.68 for all-cause stroke, all-cause bleeding and all-cause mortality respectively).

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses of 20 observational studies examining the benefits and risks of warfarin use among patients with ESRD and AF. Meta-analyses provided no evidence to suggest associations between warfarin use and all-cause stroke (HR 0.92, 95 % CI 0.74–1.16) among these patients. By contrast, warfarin use was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause bleeding (HR 1.21, 95 % CI 1.01–1.44). There were insufficient data with good quality to estimate the association between warfarin use and mortality.

We did not evaluate hemorrhagic stroke in the meta-analyses because only two studies reported hemorrhagic stroke as separate outcomes (Appendix Table 4) [22, 30]. Chan et al. reported that warfarin use was significantly associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke (HR 2.22, 95 % CI 1.01–4.91) [30], and Winkelmayer et al. also reported that warfarin use was associated with hemorrhagic stroke (HR 2.38, 95 % CI 1.15–4.96) [22].

We attempted to evaluate warfarin use vs aspirin or DOACs which was not examined in previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses, but there were not enough studies to draw conclusions regarding these comparisons. For the two studies that examined ischemic stroke outcomes comparing warfarin vs aspirin, one study showed significant increased risk from warfarin (unadjusted rate ratio (RR) 1.23, 95 % CI 1.01–1.52) [20] whereas another study showed a significant reduced risk (adjusted HR: 0.16, 95 % CI 0.04–0.66) [21]. Warfarin was associated with significantly increased risk of major bleeding compared to aspirin (adjusted RR 1.28, 95 % CI 1.19–1.39) [20]. On the other hand, dabigatran (RR 1.48, 95 % CI 1.21–1.81) and rivaroxaban (RR 1.38, 95 % CI 1.02–1.83) were associated with higher risk of hospitalization or death from bleeding when compared with warfarin [20]. In terms of stroke, the authors noted that there were too few events in the study to detect meaningful differences.

Compared to previously published systematic reviews [7–10], our review included several studies recently published [15, 16, 35] and expanded the study population to include PD [21] and stage 5 CKD [25], which were not included in these reviews [7–9, 36]. Our pooled estimate of ischemic stroke and bleeding outcomes were consistent in direction and magnitude with those reported by Li et al., Liu et al. and Dahal et al. [7, 8, 10]. On the other hand, Lee et al. found that warfarin use was associated with increased risk of any stroke (RR 1.50, 95 % CI 1.13–1.99) [9], but our result was not significant (HR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.81–1.26) because we included eight more studies in our meta-analysis [13–15, 23, 26, 28, 31, 35] and abstracted a less extreme risk estimate from one of the studies [9, 30]. We would like to point out that we abstracted the results from the intention-to-treat analysis from Shen et al. for the meta-analyses [28], whereas other systematic review abstracted the results from the as-treated analysis from Shen et al. [8]. Such difference did not change the general inferences about the lack of association between warfarin use and stroke and the increased risk of bleeding outcome.

Warfarin acts by inhibiting the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, and its anticoagulation effect is influenced by possible interactions between drugs or foods and warfarin [37]. The effectiveness of warfarin use for stroke prevention is crucially dependent on the quality of anticoagulation therapy, which can be monitored by international normalized ratio (INR) and time in therapeutic range (TTR). Only 5 of the included studies discussed the influence of INR or TTR on the outcome results [13, 20, 30–32]. Patients with suboptimal warfarin management (e.g. warfarin users who did not receive INR monitoring [30] or patients with TTR < 60 % [13]) have the highest risk for stroke and thromboembolism. Increasing baseline INR level in warfarin users was positively associated with new stroke [30]. On the other hand, patients with CKD and AF treated with warfarin to maintain an INR between 2.0 and 3.0 had a significant reduction in thromboembolic stroke [32]. Higher TTR, an indicator for good warfarin management, had protective effect against bleeding risk [31]. These results highlighted the difficulty in achieving optimal warfarin management in patients with ESRD and AF, which could help explain the heterogeneous outcomes of warfarin use in this population.

Our review has several strengths including our conduct of a comprehensive search in multiple electronic databases with the application of rigorous qualitative and quantitative assessment. We performed our qualitative assessment using the recently developed Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions, which was designed specifically for non-randomized studies that compare the health effects of two or more intervention [11], and unlike the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, does not require modification for use in reviews of effectiveness of interventions [38]. We conducted our quantitative assessment using the Knapp-Hartung method based on small-sample adjustments [12], which provided more accurate confidence limits than the DerSimonian-Laird estimator and has been advocated as an alternative method for meta-analysis with a limited number of studies [39, 40]. In addition, we were able to obtain missing outcome data from four study authors [13–16], and thus examined a greater number of studies than previous authors.

Our report also has several limitations. First, we observed high heterogeneity (I2 = 85.7 %) in all-cause mortality across the 12 studies [13–16, 22, 24, 25, 28–30, 34], which limited our ability to estimate a pooled risk estimate. In the sensitivity meta-analysis of all-cause mortality using studies that only included incident warfarin users [22, 24, 25, 28], the pooled risk estimate was not statistically significant (HR 0.99, 95 % CI 0.79–1.22). Second, we were not able to conduct meta-analysis on the association between warfarin use and hemorrhagic stroke or on the comparison between warfarin and aspirin or DOACs because there were insufficient studies available on this topic. Finally, as with all systematic review and meta-analyses, our results were limited by the quality of the available studies for inclusion. Although all included studies reported warfarin use in patients with ESRD and AF, we could not confirm that such use was indicated for AF treatment because the included studies did not report such information. We could not verify that the ischemic outcomes reported in the included studies were confirmed by imaging, since several studies were based on administrative claims or registry data [13, 22, 27, 28].

We observed substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity in the studies we examined with respect to participant characteristics, study conduct and outcome assessment. Study population seems to have significant impact on the association between warfarin use and all-cause stroke outcome as evidenced in the meta-regression. Compared to 9 studies that included patients on HD only, 6 studies that included mixed ESRD population [13, 14, 22, 23, 26] or patients on PD only [41] reported lower association between warfarin use and all-cause stroke. This may reflect heterogeneous treatment effects among subgroups of patients with ESRD and requires further investigation. Although meta-regression did not show significant impact on outcomes due to study quality or study design, these characteristics helped explain the heterogeneity observed in the included studies. A majority of the included studies had serious or critical risk of bias, particularly in the bias due to confounding [14–16, 21, 23, 24, 29, 32–35], bias in selection of participants [13, 20, 29, 31–34], and bias due to departures from intended interventions domains [13, 15, 16, 20, 21, 23, 24, 31, 32, 34, 42]. While all studies attempted to control for confounding bias by covariate adjustment or propensity score adjustment/matching except for one [15], there may be inherent confounding bias due to unobserved covariates, residual confounding or unsuccessful adjustment. Studies that included prevalent [13, 15, 16, 21, 29, 31–35, 42], rather than new warfarin users, could introduce selection bias because the effect measure was weighted toward prevalent users who had survived the early events [43]. This would underestimate the events that occur early among prevalent users when the risk of treatment-related outcome varies with time [44]. Patients that started on warfarin could discontinue the therapy and thus switched over to the non-use group, leading to bias due to departures from intended interventions [28].

Conclusions

Despite the degree of heterogeneity across studies and the bias in selected studies, our study showed that warfarin use was not associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, consistent with recent studies [7–9], and was associated with a significant higher risk for bleeding [7–10, 36] among patients undergoing HD. There was insufficient evidence with good quality to estimate the association between warfarin use and hemorrhagic stroke or mortality. Given the limitations of observational studies described above, large randomized controlled trials involving patients with ESRD and AF may be warranted to definitively evaluate the benefits and risks of warfarin. However, we recognize that such study may be too costly to be carried out, so high-quality observational studies are necessary to address the clinical decision dilemma regarding warfarin use in this population.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DOAC:

-

Direct oral anticoagulants

- ESRD:

-

End stage renal disease

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- HD:

-

Hemodialysis

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- PD:

-

Peritoneal dialysis

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- TTR:

-

Time in therapeutic range

References

Zimmerman D, Sood MM, Rigatto C, Holden RM, Hiremath S, Clase CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, prevalence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3816–22.

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–5.

Providencia R, Marijon E, Boveda S, Barra S, Narayanan K, Le Heuzey JY, Gersh BJ, Goncalves L. Meta-analysis of the influence of chronic kidney disease on the risk of thromboembolism among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(4):646–53.

Bai Y, Chen H, Yang Y, Li L, Liu XY, Shi XB, Ma CS. Safety of antithrombotic drugs in patients with atrial fibrillation and non-end-stage chronic kidney disease: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Thromb Res. 2016;137:46–52.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland Jr JC, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199–267.

Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, Charytan DM, Diez J, Hart RG, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, McCullough PA, Passman RS, et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80(6):572–86.

Li J, Wang L, Hu J, Xu G. Warfarin use and the risks of stroke and bleeding in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(8):706–13.

Liu G, Long M, Hu X, Hu CH, Liao XX, Du ZM, Dong YG. Effectiveness and safety of warfarin in dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine. 2015;94(50):e2233.

Lee M, Saver JL, Hong KS, Wu YL, Huang WH, Rao NM, Ovbiagele B. Warfarin Use and Risk of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(6):e2741.

Dahal K, Kunwar S, Rijal J, Schulman P, Lee J. Stroke, Major Bleeding, and Mortality Outcomes in Warfarin Users With Atrial Fibrillation and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Chest. 2016;149(4):951–9.

Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT, Reeves BC on behalf of the development group for ACROBAT-NRSI. A Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI), Version 1.0.0, 24 September 2014. Available from http://www.riskofbias.info. Accessed 14 Apr 2016.

Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22(17):2693–710.

Friberg L, Benson L, Lip GY. Balancing stroke and bleeding risks in patients with atrial fibrillation and renal failure: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation Cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(5):297–306.

Wang TKM, Sathananthan J, Marshall M, Kerr A, Hood C. Relationships between anticoagulation, risk scores and adverse outcomes in dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2015;25(3):243–9.

Findlay MD, Thomson PC, Fulton RL, Solbu MD, Jardine AG, Patel RK, Stevens KK, Geddes CC, Dawson J, Mark PB. Risk factors of ischemic stroke and subsequent outcome in patients receiving hemodialysis. Stroke. 2015;46(9):2477–81.

Tanaka A, Inaguma D, Shinjo H, Murata M, Takeda A. Presence of atrial fibrillation at the time of dialysis initiation is associated with mortality and cardiovascular events. Nephron. 2016;132(2):86–92.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Chan KE, Edelman ER, Wenger JB, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Dabigatran and rivaroxaban use in atrial fibrillation patients on hemodialysis. Circulation. 2015;131(11):972–9.

Chan PH, Huang D, Yip PS, Hai J, Tse HF, Chan TM, Lip GY, Lo WK, Siu CW. Ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Europace. 2015;18(5):665–71.

Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Setoguchi S, Choudhry NK. Effectiveness and safety of warfarin initiation in older hemodialysis patients with incident atrial fibrillation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(11):2662–8.

Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, Hommel K, Kober L, Lane DA, Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625–35.

Bonde AN, Lip GY, Kamper AL, Hansen PR, Lamberts M, Hommel K, Hansen ML, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Olesen JB. Net clinical benefit of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: a nationwide observational cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2471–82.

Carrero JJ, Evans M, Szummer K, Spaak J, Lindhagen L, Edfors R, Stenvinkel P, Jacobson SH, Jernberg T. Warfarin, kidney dysfunction, and outcomes following acute myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):919–28.

Chen CY, Lin TC, Yang YHK. Use of warfarin and risk of stroke and mortality in chronic dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation in taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:457–8.

Shah M, Avgil Tsadok M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Rahme E, Humphries KH, Tu JV, Behlouli H, Guo H, et al. Warfarin use and the risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing dialysis. Circulation. 2014;129(11):1196–203.

Shen JI, Montez-Rath ME, Lenihan CR, Turakhia MP, Chang TI, Winkelmayer WC. Outcomes after warfarin initiation in a cohort of hemodialysis patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(4):677–88.

Wakasugi M, Kazama JJ, Tokumoto A, Suzuki K, Kageyama S, Ohya K, Miura Y, Kawachi M, Takata T, Nagai M, et al. Association between warfarin use and incidence of ischemic stroke in Japanese hemodialysis patients with chronic sustained atrial fibrillation: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18(4):662–9.

Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R, Hakim RM. Warfarin use associates with increased risk for stroke in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(10):2223–33.

Genovesi S, Rossi E, Gallieni M, Stella A, Badiali F, Conte F, Pasquali S, Bertoli S, Ondei P, Bonforte G, et al. Warfarin use, mortality, bleeding and stroke in haemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(3):491–8.

Lai HM, Aronow WS, Kalen P, Adapa S, Patel K, Goel A, Vinnakota R, Chugh S, Garrick R. Incidence of thromboembolic stroke and of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease treated with and without warfarin. Int J Nephrol Renov Dis. 2009;2:33–7.

Wizemann V, Tong L, Satayathum S, Disney A, Akiba T, Fissell RB, Kerr PG, Young EW, Robinson BM. Atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients: clinical features and associations with anticoagulant therapy. Kidney Int. 2010;77(12):1098–106.

Khalid F, Qureshi W, Qureshi S, Alirhayim Z, Garikapati K, Patsias I. Impact of restarting warfarin therapy in renal disease anticoagulated patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ren Fail. 2013;35(9):1228–35.

Yodogawa K, Mii A, Fukui M, Iwasaki YK, Hayashi M, Kaneko T, Miyauchi Y, Tsuruoka S, Shimizu W. Warfarin use and incidence of stroke in Japanese hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessels. 2016;31(10):1676–80.

Elliott MJ, Zimmerman D, Holden RM. Warfarin anticoagulation in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review of bleeding rates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(3):433–40.

Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, Halperin JL. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation guide to warfarin therapy. Circulation. 2003;107(12):1692–711.

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, Petticrew M, Altman DG. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess (Winch Eng). 2003;(27):iii-x, 1–173.

Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, Stack CB, Meibohm AR, Guallar E, Goodman SN. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):267–70.

Guolo A, Varin C. Random-effects meta-analysis: the number of studies matters. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015.

Chan PH, Siu CW. Clinical benefit of warfarin in Dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1310–1.

Wang TKM, Sathananthan J, Hood C, Marshall M, Kerr A. Anticoagulation and outcomes of dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: 9-year cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:746.

Johnson ES, Bartman BA, Briesacher BA, Fleming NS, Gerhard T, Kornegay CJ, Nourjah P, Sauer B, Schumock GT, Sedrakyan A, et al. The incident user design in comparative effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(1):1–6.

Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Lori Rossman for helping develop the literature search strategy for the systematic review and Dr. Tianjing Li for providing helpful comments during the inception of this study.

Funding

This research was supported by the pre-doctoral training grant T32HL007024 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the doctoral dissertation fund from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Department of Epidemiology. Mara McAdams-DeMarco was supported by the American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant and Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, P30AG021334 and K01AG043501 from the National Institute on Aging. Jodi B. Segal was supported by K24AG049036 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, analysis or interpretation of the data; and preparation or final approval of the manuscript prior to publication.

Availability of data and materials

Relevant data tables can be found in the Appendix.

Authors’ contributions

JT, MMA, JBS and GCA participated in study design. JT and SL screened articles and collected data. JT synthesized study results and wrote the first draft of manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final draft of manuscript.

Competing interests

G. Caleb Alexander is Chair of the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; serves as a paid consultant to PainNavigator, a mobile startup to improve patients’ pain management; serves as a paid consultant to IMS Health; and serves on an IMS Health scientific advisory board. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Search strategies in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library

PubMed

#1 kidney failure, chronic [mh] OR renal insufficiency, chronic [mh] OR renal replacement therapy [mh] OR renal dialysis [mh] OR kidney transplantation [mh]

OR kidney disease [tw] OR renal disease [tw] OR kidney failure [tw] OR renal failure [tw] OR kidney dysfunction [tw] OR renal dysfunction [tw] OR kidney impairment [tw] OR renal impairment [tw] OR kidney insufficiency [tw] OR renal insufficiency [tw] OR ESRD [tw] OR CKD [tw] OR kidney replacement therap* [tw] OR renal replacement therap* [tw] OR dialy* [tw] OR hemodialysis [tw] OR haemodialysis [tw] OR hematodialysis [tw] OR kidney transplantation [tw] OR renal transplantation [tw] OR kidney grafting [tw]

#2 atrial fibrillation [mh]

OR atrial fibrillation [tw] OR auricular fibrillation [tw] OR atrium fibrillation [tw]

#3 anticoagulants [mh] OR warfarin [tw]

OR anticoag* [tw] OR anti-coag* [tw] OR vitamin K antagonist [tw] OR VKA [tw] OR antithrombo* [tw] OR anti-thrombo* [tw] OR warfarin [mh] OR indirect thrombin inhibitor [tw] OR Coumadin* [tw] OR coumarin* [tw] OR dabigatran [tw] OR factor Xa inhibitor [tw] OR rivaroxaban [tw] OR apixaban [tw]

#1 AND #2 AND #3

Embase

#1 ‘end stage renal disease’/exp OR ‘chronic kidney failure’/exp OR ‘renal replacement therapy’/exp OR ‘kidney transplantation’/exp

OR ‘kidney disease’:ab,ti OR ‘renal disease’:ab,ti OR ‘kidney failure’:ab,ti OR ‘renal failure’:ab,ti OR ‘kidney dysfunction’:ab,ti OR ‘renal dysfunction’:ab,ti OR ‘kidney impairment’:ab,ti OR ‘renal impairment’:ab,ti OR ‘kidney insufficiency’:ab,ti OR ‘renal insufficiency’:ab,ti OR esrd:ab,ti OR ckd:ab,ti OR (‘kidney replacement’ NEXT/1 therap*):ab,ti OR (‘renal replacement’ NEXT/1 therap*):ab,ti OR dialy*:ab,ti OR hemodialysis:ab,ti OR haemodialysis:ab,ti OR hematodialysis:ab,ti OR ‘kidney transplantation’:ab,ti OR ‘renal transplantation’:ab,ti OR ‘kidney grafting’:ab,ti

#2 ‘atrial fibrillation’/exp

OR ‘atrial fibrillation’:ab,ti OR ‘auricular fibrillation’:ab,ti OR ‘atrium fibrillation’:ab,ti

#3 ‘anticoagulant agent’/exp OR ‘warfarin’/exp OR anticoag*:ab,ti OR (anti NEXT/1 coag*):ab,ti OR ‘vitamin k antagonist’:ab,ti OR vka:ab,ti OR antithrombo*:ab,ti OR (anti NEXT/1 thrombo*):ab,ti OR warfarin:ab,ti OR ‘indirect thrombin inhibitor’:ab,ti OR coumadine:ab,ti OR dabigatran:ab,ti OR ‘factor xa inhibitor’:ab,ti OR rivaroxaban:ab,ti OR apixaban:ab,ti

#1 AND #2 AND #3

Cochrane library

ID Search

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Kidney Failure, Chronic] explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Renal Insufficiency, Chronic] explode all trees

#3 “kidney disease” or “renal disease” or “kidney failure” or “renal failure” or “kidney dysfunction” or “renal dysfunction” or “kidney impairment” or “renal impairment” or “kidney insufficiency” or “renal insufficiency” or ESRD or CKD

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Renal Replacement Therapy] explode all trees

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Renal Dialysis] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Kidney Transplantation] explode all trees

#7 kidney replacement therap* or renal replacement therap* or dialy* or hemodialysis or haemodialysis or hematodialysis or “kidney transplantation” or “renal transplantation” or “kidney grafting”

#8 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7

#9 MeSH descriptor: [Atrial Fibrillation] explode all trees

#10 “atrial fibrillation” or “auricular fibrillation” or “atrium fibrillation”

#11 #9 or #10

#12 MeSH descriptor: [Anticoagulants] explode all trees

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Warfarin] explode all trees

#14 anticoag* or anti-coag* or “vitamin K antagonist” or VKA or antithrombo* or anti-thrombo* or warfarin or “indirect thrombin inhibitor” or coumadine or dabigatran or “factor Xa inhibitor” or rivaroxaban or apixaban

#15 #12 or #13 or #14

#16 #8 and #11 and #15

Fig. 4

a Sensitivity meta-analysis: stroke outcome by warfarin use, excluding studies with prevalent warfarin users. b Sensitivity meta-analysis: bleeding outcome by warfarin use, excluding studies with prevalent warfarin users. c Sensitivity meta-analysis: mortality by warfarin use, excluding studies with prevalent warfarin users

Fig. 5

a Sensitivity meta-analysis of on stroke outcome by warfarin use, excluding studies with critical risk of bias. b Sensitivity meta-analysis of on bleeding outcome by warfarin use, excluding studies with critical risk of bias. c Sensitivity meta-analysis of on mortality outcome by warfarin use, excluding studies with critical risk of bias

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, J., Liu, S., Segal, J.B. et al. Warfarin use and stroke, bleeding and mortality risk in patients with end stage renal disease and atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol 17, 157 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0368-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0368-6