Abstract

Background

In China, men who have sex with men (MSM) face a high risk of HIV infection. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is common in this population and leads to various adverse consequences, including risky sexual behaviors, substance abuse, and poor mental health, which pose huge challenges to HIV prevention and control.

Methods

An anonymous cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the lifetime prevalence of IPV and prevalence of risky sexual behaviors during the previous 6 months in a convenience sample of 578 MSM from 15 cities covering seven geographical divisions in mainland China. The associations between IPV and risky sexual behaviors and the moderating effect of self-efficacy on these associations were explored through univariate and multivariate regression analyses.

Results

The prevalence rates of IPV perpetration and victimization were 32.5% and 32.7%, respectively. The proportions of participants who reported inconsistent condom use with regular or casual partners and multiple regular or casual sexual partners were 25.8%, 8.3%, 22.2%, and 37.4%, respectively. Multiple IPV experiences were positively associated with risky sexual behaviors; for example, any IPV victimization was positively associated with multiple regular partners, adjusted odds ratio (ORa) = 1.54, 95% CI [1.02,2.32], and multiple casual partners, ORa = 1.93, 95% CI [1.33, 2.80]. Any IPV perpetration was positively associated with inconsistent condom use with regular partners, ORa = 1.58, 95% CI [1.04, 2.40], and multiple casual partners, ORa = 2.11, 95% CI [1.45, 3.06]. Self-efficacy was identified as a significant moderator of the association between multiple casual sexual partnership and emotional IPV.

Conclusions

In conclusion, given the high prevalence of both IPV and risky sexual behaviors among Chinese MSM in this study, the inclusion of self-efficacy in interventions targeting IPV and risky sexual behaviors should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, men who have sex with men (MSM) are at high risk of HIV infection. According to a systematic analysis, the HIV prevalence among MSM populations nationwide was as high as 5.7% between 2001 and 2018[1]. Despite considerable efforts to implement HIV interventions, the prevalence of risky sexual behaviors, such as multiple sex partnership (ranged from 46.3 to 62.0%) and inconsistent condom use (ranged from 41.2 to 54.4%), remains high among MSM in China [2,3,4,5]. These high-risk behaviors have contributed substantially to the disease burden in MSM [6,7,8].

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to any stalking or other behavior by a person within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm to their current or former partner or spouse. This type of violence can occur among heterosexual or same-sex couples [9, 10], and may be experienced as a victim or perpetrator or both [11]. Recent global reviews have highlighted the high prevalence of IPV in MSM [12,13,14,15], which is comparable to or even higher than that of heterosexual women [16, 17]. Previous studies have explored the mechanisms linking IPV to risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among heterosexual females but not among MSM. IPV decreases individuals’ abilities to negotiate the timing and circumstances of sex, leading to more compulsive and condom less sex [18]. In addition, the psychological and behavioral impact of IPV is sustained [19], those who have experienced IPV may be more willing to engage in risky sexual behaviors as a maladaptive coping strategy [20]. The published literatures have reported that exposure to violence from a sexual partner is consistently associated with subsequent risky sexual behaviors, including multiple sexual partnerships, inconsistent condom use, more involvement in transactional sex, and increased substance and alcohol use during sex [18, 21,22,23]. As a major international public health issue, adverse health and behavioral consequences of IPV among MSM have been receiving increasingly attention globally, including HIV infection, substance use, poor mental health, and risky sexual behaviors [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, very few studies have been conducted among Chinese MSM exploring the association between IPV experience and risky sexual behaviors. In addition, it is worth noting that some studies have indicated that the health effects of different roles of IPV experiences (i.e., victimization vs. perpetration) often differ, with victims potentially facing additional hardship [24]. It was suggested to differentiate between IPV roles when exploring its health associations.

Self-efficacy is defined as beliefs about one’s ability to organize and execute the course of action required to manage prospective situations [31]. It was proposed by the American psychologist Dr. Albert Bandura, who argued that individuals often have expectation about specific event/behavior in their lives, including consequence and efficacy expectation. Self-efficacy determines whether an individual can effectively cope with the frustrations they may encounter in performing a specific behavior and the level of effort they are willing to put in to overcome the obstacles [32]. A high level of general self-efficacy can increase a person’s resilience to setbacks and disappointments [33]. A study in Beijing report that a high level of general self-efficacy was negatively associated with depression and anxiety among MSM, with adjusted odds ratio (ORa) of 0.88, (95% CI = 0.85, 0.92) and 0.89 (95% CI = 0.86, 0.93), respectively [34]. Another study found that improving self-efficacy was effectively in reducing depression, anxiety, risky sexual behaviors, and injected drug use [35]. Furthermore, general self-efficacy among Chinese populations in mitigating negative effects of undesirable events on behavior and health problems [36, 37]. Therefore, it is important to consider self-efficacy when conducting research on the relationship between IPV experiences and risky sexual behaviors.

In this study, we hypothesize that general self-efficacy is a protective factor against risky sexual behaviors and has a moderating effect on the relationship between IPV and risky sexual behaviors. The aims of the study were to assess the prevalence of IPV perpetrator-victim roles and different kinds of IPV; to explore the relationships among IPV experiences, general self-efficacy, and four types of risky sexual behaviors, including inconsistent condom use with regular partners, inconsistent condom use with casual partners, multiple regular sexual partners, and multiple casual sexual partners; and to test whether general self-efficacy can moderate the relationships between IPV and risky sexual behaviors.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenience sample of participants recruited from 15 cities covering seven geographical divisions in mainland China: Central (Zhengzhou, Changsha), East (Fuzhou, Hangzhou, Qingdao, Hefei), North (Taiyuan), South (Sanya, Shenzhen, Nanning), Northeast (Changchun, Harbin), Northwest (Lanzhou, Urumqi), and Southwest (Kunming). The participants were recruited by local gay-friendly non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in each city. They were briefed about the purpose of the study and its anonymous and voluntary nature before the commencement of the survey. Those who agreed to participate were asked to complete an online questionnaire, which required approximately 20 min. Upon completion, the participants received a monetary compensation of RMB15 (approximately US$2.5) for their time. During the 3-month survey period (April–June 2019), 660 MSM subjects were approached and completed the online questionnaire, 578 who met the requirements were included in the final study. The inclusion criteria were an age of at least 18 years, male gender, a self-reported history of anal intercourse with at least one man during the last 6 months, and having at least one intimate partner. In this study, intimate partner was defined as the primary male partner with whom the participant had a dating or ongoing intimate relationship [38].

Measures

Demographics

The following information about general socio-demographic characteristics was collected: age, ethnicity, current residence, education level, marital status, work status, personal income, sexual orientation, and history of sexually transmitted infection (STI).

IPV

In this study, we used the IPV-GBM scale [39] to investigate the participants’ lifetime experiences of victimization and perpetration of five types of IPV, including physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling, and emotional IPV. The IPV-GBM scale has good internal reliability, Cronbach’s α > 0.90, and has been used in many studies of MSM [14, 40]. An example item used to assess physical IPV is “Have the following ever occurred during a heated argument between you and an intimate partner: destruction of property, hitting with fists, pushing, kicking, slapping, beating, threats of violence or other physical threats?” To clearly distinguish whether the participants had been the perpetrator or victim of IPV, we set four response options for the items: (A) I have done the above to my partner; (B) My partner has done the above to me; (C) Both A and B; and (D) Neither A nor B. We defined the participants who chose A or C as IPV perpetrators and those who chose B or C as IPV victims. In our study, Cronbach’s α = 0.71 for this scale.

Risky sexual behaviors

We included four risky sexual behaviors as outcome variables: inconsistent condom uses with regular partners, inconsistent condom uses with casual partners, multiple regular sexual partners, and multiple casual sexual partners.

Inconsistent condom uses with regular/casual partners We used two items to define and assess inconsistent condom uses with regular and casual partners (coded as 0 or 1). The participants were asked to answer the following two questions: In the past 1 month, how often did you use condoms during anal sex with a regular partner? In the past 1 month, how often did you use condoms during anal sex with a casual partner? We set four response options for these items: (A) never, (B) occasionally, (C) regularly, and (D) every time. The participants who selected A, B, and C were defined as inconsistent condom users (all coded as 1 in the follow-up analysis).

Multiple regular/casual sexual partners The participants were asked to answer the following questions: How many sexual partners in total have you had in the past 6 months? How many of them were regular sexual partners and how many were casual sexual partners? A number of casual and/or regular partners > 1 was defined as multiple sexual partners (all coded as 1 in the follow-up analysis).

Self-efficacy

We used the 10-item General Self-Efficacy (GSE) scale to assess self-efficacy. Example items include “I can face difficulties calmly because I trust my ability to deal with them” and “I can solve most problems if I put in the necessary effort.” The GSE scale has been adapted for the Chinese MSM population [41, 42] and has been used in previous study [34]. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all correct) to 4 (completely correct). The total scores ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-efficacy. In this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.93 for this scale.

Statistical analysis

We first applied a one-way logistic regression model to capture background variables that were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with the four risky sexual behaviors identified above. Second, we used a multiple logistic regression analysis to obtain ORa values and 95% CIs of these associations adjusted for background variables. Finally, a hierarchical logistic regression was conducted to examine the moderating effect of self-efficacy. The variables were included in this analysis in four steps: significant background variables; different types of IPV victimization or perpetration; general self-efficacy; and interaction terms between different species of IPV and self-efficacy, such as emotional IPV perpetration × self-efficacy. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (Version 25). We set the level of statistical significance at p = 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Most of the participants were younger than 30 years (62.8%), and the majority were of Han ethnicity (91.3%). More than half had completed a university education (54.3%) and held full-time employment (66.1%). Nearly half of them had a monthly income in the range of CNY2001–5000 (47.9%). In terms of marital status and sexual orientation at the time of the survey, 51.2% were single, 36.0% had a male partner, and 81.3% self-identified as gay. Approximately one in five (18.2%) reported having had an STI.

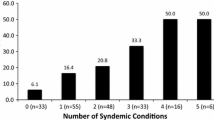

The rates of inconsistent condom use with regular and casual partners were 25.8% (149/578) and 8.3% (48/578), respectively. The prevalence of multiple regular sexual partners and multiple casual sexual partners was 22.2% (128/578) and 37.4% (216/578), respectively. Table 1 presents the basic demographic characteristics and risky sexual behaviors reported by the participants.

IPV

Any IPV The lifetime prevalence of any experience of IPV (i.e., without role differentiation) in our sample was 41.2% (238/578). The lifetime prevalence rates of experience of any physical, sexual, monitoring, controlling, and emotional IPV were 11.6% (67/578), 14.0% (81/578), 20.9% (121/578), 12.3% (71/578), and 22.5% (130/578), respectively.

IPV perpetration In our sample, 32.5% of the participants (188/578) reported that they had been involved in any type of IPV perpetration. Emotional perpetration was the most frequent type, at 17.1% (99/578), followed by monitoring perpetration, at 15.2% (88/578). Sexual perpetration was the least prevalent, at 6.9% (40/578). Controlling IPV and physical IPV perpetration were reported by 9.5% (55/578) and 9.2% (53/578) of the participants, respectively.

IPV victimization In our sample, 32.7% of the participants (189/578) reported that they had experienced any type of IPV victimization. Again, emotional victimization was the most frequent type, at 17.1% (99/578), followed by monitoring victimization, at 15.1% (87/578). Controlling victimization was reported least frequently, at 9.2% (53/578). Sexual and physical victimization were reported by 11.6% (67/578) and 9.5% (55/578) of the participants, respectively.

Self-efficacy

In this study, the mean self-efficacy score was 27.45 (SD = 6.00). In a background variable-adjusted analysis, self-efficacy was found to have negative associations with two risky sexual behaviors: inconsistent condom uses with regular partners, ORa = 0.96, 95% CI [0.93, 1.00], and multiple casual sexual partners, ORa = 0.97, 95% CI [0.94, 1.00]. It was not significantly associated with inconsistent condom use with a casual partner or multiple regular sexual partners.

Associations between IPV and risky sexual behaviors

Association between IPV and inconsistent condom uses with regular partners In a univariate analysis, we found significant associations between sexual orientation, marital status, and inconsistent condom uses with regular partners, and these were included as control variables in a multiple logistic regression. Generally, any IPV experience, ORa = 1.51, 95% CI [1.00, 2.29], sexual IPV, ORa = 1.86, 95% CI [1.06, 3.24], and monitoring IPV, ORa = 1.90, 95% CI [1.18, 3.05], were positively associated with inconsistent condom uses with regular partners. Specifically, any IPV perpetration, ORa = 1.58, 95% CI [1.04, 2.40], and monitoring IPV perpetration, ORa = 2.25, 95% CI [1.32, 3.81], were associated significantly with inconsistent condom uses with regular partners. The adjusted logistic regression also revealed that sexual, ORa = 2.11, 95% CI [1.16, 3.85], control, ORa = 1.94, 95% CI [1.00, 3.76], and emotional IPV victimization, ORa = 1.71, 95% CI [1.02, 2.87], were positively associated with inconsistent condom uses with regular partners.

Association between IPV and inconsistent condom uses with casual partners In a univariate analysis, we observed significant associations between STI, marital status, and inconsistent condom use with casual partners, and these were subsequently included as control variables in a multiple logistic regression. Generally, any sexual, ORa = 2.35, 95% CI [1.15, 4.84], and any controlling IPV, ORa = 2.48, 95% CI [1.12, 5.45], were positively associated with inconsistent condom uses with casual partners. Specifically, only sexual IPV perpetration, ORa = 2.58, 95% CI [1.01, 6.59], had a significant association with inconsistent condom uses with casual partners. Similarly, the adjusted logistic regression also revealed that only controlling IPV victimization, ORa = 2.39, 95% CI [1.011, 5.66] was positively associated with inconsistent condom uses with casual partners.

Association between IPV and multiple regular sexual partners In a univariate analysis, we found significant associations between STI, marital status, and multiple regular sexual partners, and these were subsequently included as control variables in a multiple logistics regression. Generally, any sexual IPV, ORa = 2.16, 95% CI [1.30, 3.60], was positively associated with multiple regular sexual partners. Specifically, only sexual IPV perpetration, ORa = 2.43, 95% CI [1.24, 4.80], was significantly associated with multiple regular sexual partners. Similarly, the adjusted logistic regression revealed that any IPV victimization, ORa = 1.54, 95% CI [1.02, 2.32], and sexual IPV victimization, ORa = 2.25, 95% CI [1.30, 3.88] were positively associated with multiple regular sexual partners.

Association between IPV and multiple casual sexual partners In a univariate analysis, we found significant associations between ethnicity, marital status, STI, and multiple casual sexual partners, and these were subsequently included as control variables in a multiple logistic regression. Generally, any exposure to IPV, ORa = 2.02, 95% CI [1.41, 2.90], sexual IPV, ORa = 1.69, 95% CI [1.03, 2.77], controlling IPV, ORa = 2.27, 95% CI [1.34, 3.84], and emotional IPV, ORa = 1.65, 95% CI [1.09, 2.50], were positively associated with multiple casual sexual partners. Specifically, any IPV perpetration, ORa = 2.11, 95% CI [1.45, 3.06], monitoring IPV perpetration, ORa = 1.71, 95% CI [1.05, 2.776], and emotional IPV perpetration, ORa = 1.74, 95% CI [1.10, 2.75], showed significant associations with multiple casual sexual partners. It also revealed that any IPV, ORa = 1.93, 95% CI [1.33, 2.80], sexual IPV, ORa = 1.73, 95% CI [1.01, 2.96], and controlling IPV victimization, ORa = 3.21, 95% CI [1.75, 5.89], were positively associated with multiple casual sexual partners. Details of these associations between IPV and risky sexual behaviors are shown in Table 2.

Moderating effect of self-efficacy on the association of IPV with risky sexual behaviors

As shown in Table 3, we observed a significant moderating effect of self-efficacy on the associations of multiple casual sexual partners with any emotional IPV (B = 0.09, p < 0.05), emotional IPV perpetration (B = 0.10, p < 0.05), and emotional IPV victimization (B = 0.11, p < 0.05). However, self-efficacy did not have a significant moderating effect on the associations of the four risky sexual behaviors with the other types of IPV exposure (data not shown).

Discussion

The study explored the association between IPV experience and risky sexual behaviors among Chinese MSM, also examined the potential moderating effect of self-efficacy on these relationships.

The IPV prevalence of our sample was consistent with the results of previous studies that confirmed a high prevalence (18.7–51.0%) of IPV among MSM in China [2, 43,44,45,46,47]. In addition, unlike some foreign studies where victimization rates were significantly higher than perpetration rates [48, 49], the prevalence rates of perpetration and victimization in this sample were similar, possible reasons for the difference may derive from study locations and measurements, in addition, our sample was younger and mostly from urban areas, a population group with a higher risk of IPV perpetration [50]. A study has shown a significant association between IPV perpetration and risky sex, including inconsistent or no condom use during sex or forcing sexual intercourse without a condom [22]. Our results suggest that equal attention should be given to victimization and perpetration when addressing IPV among Chinese MSM. Notably, our study also reaffirmed emotional IPV as the most prevalent reported by MSM in China [2, 14]. A possible reason was due to the specific identity of MSM, events involving sexual identity, homophobia, jealousy, power differentials, and external discrimination could all trigger conflict between partners and cause emotional violence, and emotional violence has been identified as the most common and harmful form of violence in MSM [51].Therefore, emotional IPV should be given more attention when designing relevant interventions targeted at Chinese MSM.

When exploring the relationships between specific types of IPV and risky sexual behaviors, we found that any sexual IPV was associated with all risky sex included while physical IPV had no effect with any of the four risky sexual behaviors. The result indicated the adverse effects of sexual IPV on risky sex, which was consistent with the previous research [52]. Unlike sexual violence often directly influences the occurrence of risky sexual behaviors, physical violence was unlikely to be accompanied by sexual intercourse. However, several existing studies on females had confirmed sexual IPV is likely to be accompanied by physical IPV [53, 54], which suggested that physical IPV may have an indirect rather than a direct effect on risky sex. Experience with any emotional IPV was positively correlated with multiple casual sexual partners.

Among casual partners, we reported IPV victimization would increase the number of casual partner, however, it did not associated with inconsistent condom use. We hypothesized that IPV experience with regular partner may be the trigger event for MSM to seek for casual sexual partners outside of their relationships. However, condom use was more dependent on participants’ risk perceptions of HIV/STI infection by casual partners [55], which usually wasn’t related to their IPV experiences with their regular partners. However, from a public health perspective, the risk of STI/HIV infection increases considerably with the increased number of sexual partners, even when the condom use rate is unchanged. Empirical and modeling studies have demonstrated that the number of sexual partners is strongly correlated with the risk of HIV infection [56]57. In contrast, we reported that IPV mainly influenced condom use among regular partners while it had limited impact on the number of regular partners. Studies showed that physical, sexual, emotional, and control IPV could reduce the effectiveness of condom use negotiation; as the number of IPV exposure types increased, the rate of successful negotiation decreased [27]. In addition, violent relationship dynamics may increase the difficulties for MSM to negotiate for safe sex [58]. These suggested that condom use with regular partners may be closely related to negotiation skills and power dominance roles between intimate partners. Therefore, we should aim to increase risk awareness and health education to reduce the occurrence of risky sex associating with multiple casual partners and to strengthen the empowerment and negotiation skill training in interventions for MSM with IPV experiences, especially for the victims.

Consistent with previous studies [24], we observed the negative effect of high self-efficacy against risky sexual behaviors, including inconsistent condom use with regular partners and multiple sexual casual partners. Self-efficacy was also found for the first time to have a moderating effect on the association between emotional IPV and multiple casual sexual partners. Aspects of self-efficacy, such as positive attitude toward the self, a sense of personal competence, and confidence in the ability to handle problems reduce the likelihood that those who have experienced IPV will engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as seeking comfort in a new casual partner. These demonstrated the importance of efforts to improve individual self-efficacy among Chinese MSM.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it involved only a cross-sectional survey. Therefore, we cannot infer a definitive causal relationship and will need to conduct further longitudinal studies to explore and corroborate the associations identified herein. Second, the sample was recruited by convenience sampling and may be subject to selection bias, as individuals who were familiar with NGOs may have been more likely to participate. Engagement in risky sexual behaviors may have been less frequent in our sample compared with the general population, due to the support provided by the NGOs. Additionally, the collection of self-reported data via online questionnaires may have led to reporting bias. Third, we used the GSE scale to measure self-efficacy and did not distinguish between context-specific types of self-efficacy, which resulted in relatively weak protective and moderating effects. Finally, the results of this study may only be applicable to the urban MSM population in China and are not generalizable to other contexts.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the high prevalence of IPV and risky sexual behaviors in a sample of Chinese MSM and identified the adverse effects of IPV experiences on the prevalence of risky sexual behaviors. In addition, we also tested the moderating effect of self-efficacy on the association between IPV and risky sexual behaviors and found that higher self-efficacy mitigated this association. Our results thus highlight some key targets in the development of interventions for the MSM population with IPV experience and suggest that increasing self-efficacy in this group may reduce the prevalence of risky sexual behaviors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental organizations

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- IPV-GBM:

-

Intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men scale

- GSE:

-

General self-efficacy

References

Dong MJ, Peng B, Liu ZF, Ye QN, Liu H, Lu XL, et al. The prevalence of HIV among MSM in China: a large-scale systematic analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1000.

Davis A, Best J, Wei C, Luo J, Van Der Pol B, Meyerson B, et al. Intimate partner violence and correlates with risk behaviors and HIV/STI diagnoses among men who have sex with men and men who have sex with men and women in china: a hidden epidemic. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(7):387–92.

Wang X, Wang Z, Jiang X, Li R, Wang Y, Xu G, et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between sexual compulsivity and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in shanghai, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):465.

Zhang X, Jia M, Chen M, Luo H, Chen H, Luo W, et al. Prevalence and the associated risk factors of HIV, STIs and HBV among men who have sex with men in Kunming, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(11):1115–23.

Zhu Z, Yan H, Wu S, Xu Y, Xu W, Liu L, et al. Trends in HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among men who have sex with men from 2013 to 2017 in Nanjing, China: a consecutive cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1): e021955.

Althoff MD, Anderson-Smits C, Kovacs S, Salinas O, Hembling J, Schmidt N, et al. Patterns and predictors of multiple sexual partnerships among newly arrived Latino migrant men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2416–25.

Yang H, Hao C, Huan X, Yan H, Guan W, Xu X, et al. HIV incidence and associated factors in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Nanjing, China. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(4):208–13.

Beyrer C, Baral SD, vanGriensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):367–77.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence. Accessibility verified April 6, 2021.

World Health Organization & Pan American Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432. Accessibility verified April 6, 2021.

Melander LA, Noel H, Tyler KA. Bidirectional, unidirectional, and nonviolence: a comparison of the predictors among partnered young adults. Violence Vict. 2010;25(5):617–30.

Chong ES, Mak WW, Kwong MM. Risk and protective factors of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28(7):1476–97.

Tran A, Lin L, Nehl EJ, Talley CL, Dunkle KL, Wong FY. Prevalence of substance use and intimate partner violence in a sample of A/PI MSM. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(11):2054–67.

Wei D, Hou F, Hao C, Gu J, Dev R, Cao W, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and associated factors among men who have sex with men in China. J Interpers Violence. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519889935.

Davis DA, Rock A, Santa Luce R, McNaughton-Reyes L, Barrington C. Intimate partner violence victimization and mental health among men who have sex with men living with HIV in Guatemala. J Interpers Violence. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520928960.

Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013;14(2):168–85.

Goldberg NG, Meyer IH. Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: results from the California health interview survey. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28(5):1109–18.

Dunkle KL, Decker MR. Gender-based violence and HIV: reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):20–6.

Wang SH, Rowley W. Rape: how men, the community and the health sector respond. Geneva: Sexual Violence Research Initiative and the World Health Organization; 2007.

Johnson SD, Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB. A tripartite of HIV-risk for African American women: the intersection of drug use, violence, and depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2):169–75.

Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2107–14.

Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–8.

Dunkle KL, Jewkes R, Nduna M, Jama N, Levin J, Sikweyiya Y, et al. Transactional sex with casual and main partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1235–48.

Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, Bacchus LJ. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3): e1001609.

Dustin TD, William CG, Christopher BS, William JB, Forrest AB, Jermaine SB, et al. A study of intimate partner violence, substance abuse, and sexual risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in a sample of geosocial-networking smartphone application users. Am J MEN’s Health. 2018;12(2):1–10.

Mthembu JC, Khan G, Mabaso M, Simbayi LC. Intimate partner violence as a factor associated with risky sexual behaviors and alcohol misuse amongst men in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(9):1132–7.

Stephenson R, Freeland R, Finneran C. Intimate partner violence and condom negotiation efficacy among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. Sex Health. 2016;13:366–72.

Ogunbajo A, Oginni OA, Iwuagwu S, Williams R, Biello K, Mimiaga MJ. Experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) is associated with psychosocial health problems among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in Nigeria, Africa. J Interpers Violence. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520966677.

Stults CB, Javdani S, Greenbaum CA, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Intimate partner violence and substance use risk among young men who have sex with men: the P18 cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:54–62.

Wong JYH, Choi EPH, Lo HHM, Wong W, Chio JHM, Choi AWM, et al. Intimate partner sexual violence and mental health indicators among chinese emerging adults. J Interpers Violence. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519872985.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy theory: towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In: Encyclopedia of human behavior. Academic Press, Camnridge. 1994; 4:71–81

Wang N, Wang S, Qian HZ, Ruan Y, Amico KR, Vermund SH, et al. Negative associations between general self-efficacy and anxiety/depression among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. AIDS Care. 2019;31(5):629–35.

Murphy DA, Stein JA, Schlenger W, Maibach E. Conceptualizing the multidimensional nature of self-efficacy: assessment of situational context and level of behavioral challenge to maintain safer sex. National Institute of Mental Health Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):281–90.

Li Y, Zhang J, Wang S, Guo S. The effect of presenteeism on productivity loss in nurses: the mediation of health and the moderation of general self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1745.

Lu CQ, Siu OL, Cooper CL. Managers’ occupational stress in China: the role of self-efficacy. Personal Individ Differ. 2005;38(3):569–78.

Davis A, Kaighobadi F, Stephenson R, Rael C, Sandfort T. Associations between alcohol use and intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):400–6.

Stephenson R, Finneran C. The IPV-GBM scale: a new scale to measure intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6): e62592.

Stephenson R, Finneran C. Receipt and perpetration of intimate partner violence and condomless anal intercourse among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2253–60.

Han Y, Xia D, Sun Y, Li G, Lu H, He X, et al. HIV prevalence and its related factors among men who have sex with men in Beijing. Chin J AIDS STD. 2013;19(06):399–412.

Qiu X, Zhang J, Xie A, Ye H, Li S, Gong W, et al. Study on the effect of general self-efficacy on knowledge and behavior about AIDS in MSM. Pract Prev Med. 2013;20(11):1297–300.

Liu Y, Zhang Y, Ning Z, Zheng H, Ding Y, Gao M, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. Biosci Trends. 2018;12(2):142–8.

Dunkle KL, Wong FY, Nehl EJ, Lin L, He N, Huang J, et al. Male-on-male intimate partner violence and sexual risk behaviors among money boys and other men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):362–5.

Ibragimov U, Harnisch JA, Nehl EJ, He N, Zheng T, Ding Y, et al. Estimating self-reported sex practices, drug use, depression, and intimate partner violence among MSM in China: a comparison of three recruitment methods. AIDS Care. 2017;29(1):125–31.

Li D, Zheng L. Intimate partner violence and controlling behavior among male same-sex relationships in china: relationship with ambivalent sexism. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(1–2):208–30.

Wang HY, Wang N, Chu ZX, Zhang J, Mao X, Geng WQ, et al. Intimate partner violence correlates with a higher HIV incidence among MSM: a 12-month prospective cohort study in Shenyang, China. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2879.

Bacchus LJ, Buller AM, Ferrari G, Peters TJ, Devries K, Sethi G, et al. Occurrence and impact of domestic violence and abuse in gay and bisexual men: a cross sectional survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(1):16–27.

Miltz AR, Lampe FC, Bacchus LJ, McCormack S, Dunn D, White E, et al. Intimate partner violence, depression, and sexual behavior among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the PROUD trial. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):431.

Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Sheidow AJ, Henry DB. Partner violence and street violence among urban adolescents: do the same family factors relate? J Res Adolesc. 2001;11:273–95.

Woodyatt CR, Stephenson R. Emotional intimate partner violence experienced by men in same-sex relationships. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(10):1137–49.

Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate partner violence, minority stress, and sexual risk-taking among US men who have sex with men. J Homosex. 2014;61(2):288–306.

Zilkens RR, Phillips MA, Kelly MC, Mukhtar SA, Semmens JB, Smith DA. Non-fatal strangulation in sexual assault: a study of clinical and assault characteristics highlighting the role of intimate partner violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;43:1–7.

McQuown C, Frey J, Steer S, Fletcher GE, Kinkopf B, Fakler M, et al. Prevalence of strangulation in survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(7):1281–5.

Lightfoot M, Song J, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Newman P. The influence of partner type and risk status on the sexual behavior of young men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(1):61–8.

Gilmour S, Li J, Shibuya K. Projecting HIV transmission in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8): e43473.

You X, Gilmour S, Cao W, Lau JT, Hao C, Gu J, et al. HIV incidence and sexual behavioral correlates among 4578 men who have sex with men (MSM) in Chengdu, China: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):802.

Casey EA, Querna K, Masters NT, Beadnell B, Wells EA, Morrison DM, et al. Patterns of intimate partner violence and sexual risk behavior among young heterosexually active men. J Sex Res. 2016;53(2):239–50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks to all the participants in this study. Special thanks to the local NGO, Chengdu Tongle Health Counseling Service Center, for its support, and all field workers for their contribution to data collection.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81803334, 71774178, 71974212), The Science and Technology Innovation Committee of Shenzhen Municipality (JCYJ20190809162411393), a Major Infectious Disease Prevention and Control of the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2018ZX10715004), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2017A020212006), and Science and Technology Research Project of Guangzhou (201607010332, 201607010368).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design and preparation: JL and FH; Data collection: DW, LP and XY; Data analysis: YZ, FH, CC; Original manuscript: YZ, FH, JL. Review and editing: YZ, FH, CH, JG, YH, JL. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained ethical approval of the study from the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University ([2018] 049).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Hou, F., Chen, C. et al. Moderating effect of self-efficacy on the association of intimate partner violence with risky sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men in China. BMC Infect Dis 21, 895 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06618-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06618-2