Abstract

Background

HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China is rising rapidly, and unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) is associated with HIV transmission. Recent research has shown that associations between UAI and other factors can differ according to the type of sex partners, including regular partners and casual partners. This study aimed to explore the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI according to partner type among MSM in Shanghai, China.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 547 MSM from four districts in Shanghai, China. All participants were recruited using snowball sampling. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale was used to evaluate participants’ sexual compulsivity. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with sexual compulsivity and UAI. The mediation effects of substance use before sex on the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI were tested through mediation analyses.

Results

After adjusting for sociodemographic variables, sexual compulsivity was associated with overall UAI (adjusted odds ratios [AOR] = 1.039, 95% confidence intervals [CI] = 1.004–1.075), UAI with non-regular sex partners (AOR = 1.089, 95% CI = 1.033–1.148) and UAI with commercial sex partners (AOR = 1.185, 95% CI = 1.042–1.349). No significant association was found between sexual compulsivity and UAI with regular sex partners (AOR = 1.029, 95% CI = 0.984–1.077). Mediation analyses indicated that the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI was not mediated by either alcohol use before sex or drug use before sex.

Conclusions

The association between sexual compulsivity and UAI varies depending on the type of UAI partner. Therefore, individuals may engage in different types of UAI for different reasons, and tailored HIV cognitive–behavioral intervention programs are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV transmission in China occurs in various ways, including intravenous drug use, blood or plasma transfusion, and high-risk sexual behaviors, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) [1]. Among people living with HIV (PLWH) in China, the approximate percentage of infections from unprotected male-to-male sexual contact was 7.3, 11.0, 14.7, and 17.4% in 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011, respectively [2,3,4,5]. Related data suggest that the fastest increase in HIV transmission in China is found in MSM [6, 7]. MSM have a disproportionately high HIV prevalence, which can be ascribed to the high prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) [8, 9], one of the riskiest sexual behaviors for HIV transmission [10,11,12,13] in this subpopulation. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of UAI is urgently needed to prevent the rapid spread of HIV among MSM. There are many factors related to UAI, such as drug use [14, 15], depressive symptoms [16], lower risk of perception of UAI [16, 17], non-disclosure of sexual orientation to parents [18], self-efficacy in condom use [19], sexual sensation seeking [15, 20], and sexual compulsivity [19, 21,22,23,24,25].

Sexual compulsivity is “an insistent, repetitive, intrusive, and unwanted urge to perform specific acts often in ritualized or routinized fashions” [24], which is characterized by sexual fantasies and can interfere with personal, interpersonal, and vocational activities [26,27,28]. Individuals who are incapable of controlling sexual impulses sufficiently and are preoccupied with sexual activities may tend to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors disregarding the probability of contracting HIV and other potential adverse consequences [29,30,31]. To assess the degree of sexual compulsivity, Kalichman and colleagues developed the 10-item Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS), which was based on a self-assisted guide for self-reported sexual addiction [24, 32,33,34]. This scale has been widely used and shown to be reliable among sexually active individuals, including MSM and heterosexual men and women [15, 24, 34,35,36,37]. High sexual compulsivity, in many studies, has been certified that corresponded to high-risk sexual behaviors in MSM [38, 39]. For MSM with different ethnic and racial backgrounds, sexual compulsivity has been recognized as a stable personality trait [40]. The SCS has been translated into Chinese and back-translated into English by Chinese researchers to verify its reliability and validity [36]. The validated Chinese version of sexual compulsivity scale used in the present study can also be applied in many other populations in China as long as they can read and write the same Chinese language [20].

Many previous studies have found a significant association between UAI and sexual compulsivity [19, 21,22,23,24,25]. Some research has examined this high-risk sexual behavior in relation to the type of sexual partner with whom participants practice UAI [20, 36, 41,42,43,44,45,46]. These studies have found variation in the relationships between independent variables and different types of UAI (including UAI with regular sex partners, UAI with casual sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners). In the meantime, some survey studies found the prevalence rates of different types of UAI vary [42, 45,46,47,48,49]. Wang et al. (2017) suggested that cognitive variables, psychological factors, emotion-related variables, and social-structural factors are strongly associated with UAI with regular and/or non-regular sexual partners [41]. Therefore, research on the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI according to partner type may help to inform partner type-specific HIV prevention strategies that target MSM. In addition, substance use has been recognized as a robust predictor of UAI [14, 15] and a mediator of the association between sexual compulsivity and UAI [21]. Therefore, testing for mediation by substance use before sex was conducted to understand whether the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI is mediated by substance use.

We conducted this cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China, and evaluated relationships between sexual compulsivity and different types of UAI. The main hypotheses were 1) sexual compulsivity is associated with UAI, and 2) the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI varies according to partner type.

Methods

Setting, sample and recruitment

Shanghai, a large cosmopolitan city with relatively more tolerance to people with diversified sexuality, MSM in particular, making it an appropriate social setting for studies targeting MSM. This cross-sectional study used a snowball sampling method to recruit eligible participants from the Changning, Jingan, Zhabei, and Pudong districts from March 2014 to August 2014. This method initially identifies subgroup members from whom the targeted data can be collected; then these initial members serve as “seed” to recruit new eligible participants. These participants, in turn, are encouraged to recruit other new participants until the sample size reaches the goal. Eligibility criteria in this research included male gender, age above 16 years, and having had UAI with another man in the past 6 months. With the help of the local Center for Disease Control and Prevention and some non-government organizations, 5 to 10 eligible persons from each district were enrolled as “seeds”. A total of 547 eligible participants were enrolled. Each participant signed an informed consent form before completing a questionnaire. Participants received 100 CNY (about 15.5 USD) as compensation. Trained workers introduced the survey to participants and answered any questions they had. Subsequently, anonymous face-to-face interviews were carried out to help participants to complete a series of questionnaires collecting sociodemographic data, data on behavioral variables, and SCS scores. At the end of this process, one participant’s data were excluded because he had not specified the partner type in his response.

Ethics, consent, and permissions

Each participant provided written, informed consent before participation. This study strictly complied with American Psychological Association standards and was approved by the institutional review board of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Public Health.

Measures

Questionnaire data on sociodemographics, behavioral variables, and total SCS scores comprised the independent variables.

Sociodemographics

Respondents were asked about their age, highest educational level, current marital status (with women), monthly salary, residential status, and self-reported sexual orientation.

Behavioral variables

Behavioral variables measured were overall UAI and different forms of UAI according to partner type in the past 6 months, as well as substance use before sex. Individuals who reported inconsistent condom use (any at all, over the last 6 months) during sex with men were coded as having had UAI with male sex partners; this operational recording has been commonly used in published studies [50, 51]. Information about the type of sexual partner was also obtained. Regular sex partners were defined as boyfriends; namely, those individuals in stable relationships with participants. Non-regular sex partners were defined as sexual partners who were neither regular nor commercial. Commercial sex partners were defined as partners receiving money from participants for transactional sex. Some published studies on sexual activities have used similar definitions for sex partner types [52,53,54].

Sexual compulsivity

The degree of sexual compulsivity was assessed using the SCS, a 10-item, four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score ranges from 10 to 40. Sample items included “My sexual appetite has gotten in the way of my relationships,” “My sexual thoughts and behaviors are causing problems in my life” and “I sometimes fail to meet my commitments and responsibilities because of my sexual behaviors.” A higher total score indicates a greater degree of sexual compulsivity. Cronbach’s α for this scale is 0.86, as reported by Kalichman & Rompa [24], and was 0.853 for the current sample.

Statistical analysis

Internal reliability was assessed by using the Cronbach’s α. Descriptive analysis was performed, then the associations between background variables and sexual compulsivity were examined using t-tests and ANOVA. In addition, multivariable logistic regression was conducted to determine the association between independent variables and different types of UAI, obtained their adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The criterion of statistical significance was p < .05. At the final stage, meditational analyses were conducted by computing the separate ZMediation, which was recommended by a published study for categorical mediators and dependent variables [55]. All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Mediation analyses

The aims of this research included investigating whether substance use before sex as a robust predictor of UAI mediate the relationship between sexual compulsivity and UAI. According to a published study recommending the solution for meditational analyses using categorical mediators and dependent variables, the ZMediation was computed [55]. The mediation effect is significant at the level of α = 0.05 if the ZMediation exceeds |1.96| (for a 2-tailed test with α = 0.05).

Results

Sample description

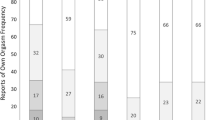

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of participant sociodemographic characteristics and Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for sexual compulsivity. Most respondents were single non-local people aged 25–40 years, with a college-level education or above and self-reported as gay/homosexual. The distribution of income was even. Regarding the substance use, 49.3% of participants reported alcohol use before sex, and 96.9% of participants reported no drug use before sex during the 6 months prior to the study. Of the participants, 54.4% were coded as having had UAI with male sex partners in the past 6 months. Regarding sex partners, 61.5% of respondents reported having regular sex partners and 50.9% of these had had UAI with regular sex partners in the past 6 months; 51.8% of respondents reported having non-regular sex partners and 42.8% of these had had UAI with non-regular sex partners in the past 6 months; 14.3% of respondents reported having commercial sex partners and 55.1% of these had had UAI with commercial sex partners in the past 6 months. The range, mean and median of participants’ SCS scores were 30, 22.41 and 23.00 respectively.

Table 2 shows total SCS scores by sociodemographic and behavioral variables. There were significant between-group differences in SCS scores for highest educational level, current marital status, residential status, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners. Individuals having had UAI with non-regular sex partners and with commercial sex partners have a higher SCS mean scores than individuals having had UAI with regular sex partners.

Relationships between background variables and UAI, UAI with regular sex partners, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners

Analyses showed that highest educational level and monthly salary were significantly related to UAI. Age was significantly related to UAI with regular sex partners. Age, highest educational level, and self-reported sexual orientation were significantly related to UAI with non-regular sex partners. Self-reported sexual orientation was significantly related to UAI with commercial sex partners. Table 3 presents the main outcome of the analysis.

Relationships between sexual compulsivity and UAI, UAI with regular sex partners, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners

The relationships between sexual compulsivity and UAI, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners were significant. AORs for the associations between sexual compulsivity and different types of UAI were calculated after adjusting for background variables. Sexual compulsivity was found to be associated with overall UAI (AOR = 1.039, 95% CI = 1.004–1.075), UAI with non-regular sex partners (AOR = 1.089, 95% CI = 1.033–1.148) and UAI with commercial sex partners (AOR = 1.185, 95% CI = 1.042–1.349). No significant association was found between sexual compulsivity and UAI with regular sex partners (AOR = 1.029, 95% CI = 0.984–1.077).

After adjusting for the effects of background variables, the results showed that for each unit increase in the total SCS score, the odds of having had UAI increased by 3.9%, the odds of having had UAI with non-regular sex partners increased by 8.9% and the odds of having had UAI with commercial sex partners increased by 18.5%. Given the range of the total SCS score, these increases in odds are considerable. Table 3 presents the main outcome of this analysis.

Mediation analyses

The meditational analyses indicated that the relationships between sexual compulsivity and UAI, UAINP, UAICP were not mediated by either alcohol use before sex or drug use before sex. Table 4 presents the main outcomes of the analyses.

Discussion

This survey explored the relationships between sexual compulsivity and different types of UAI among MSM in Shanghai, China. The prevalence rates for different types of UAI among participants were 50.9% (UAI with regular sex partners), 42.8% (UAI with non-regular sex partners), and 55.1% (UAI with commercial sex partners). These statistics are in line with previous study [42, 45,46,47,48,49], indicating that the prevalence rate of UAI with regular sex partners is higher than the prevalence rate of UAI with non-regular sex partners. The findings also showed that the association between sexual compulsivity and UAI varied according to partner type. In other words, sexual compulsivity was significantly associated with UAI in general, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners. No significant association was observed between sexual compulsivity and UAI with regular sex partners. This result is consistent with findings from several previous studies, suggesting that individuals who exhibit a greater degree of sexual compulsivity are more likely to engage in UAI with casual sex partners than those who exhibit less sexual compulsivity [17, 23, 32,33,34, 56]. In addition, we investigated potential mediators of the relationships between sexual compulsivity and UAI, UAINP, UAICP, and failed to find any significant mediation effect. More research is warranted to understand whether substance use before sex mediates the association between sexual compulsivity and UAI in Chinese MSM.

The choice of variable type (categorical variable versus continuous variable) is a critical issue that could potentially influence the result of statistical analyses. Before presenting results produced by using the continuous SC variable in Table 3, multivariable analyses were carried out respectively to compare the results obtained by using the continuous SCS variable and by using the categorical SCS variable. In despite of a lack of established, defined cut-point to designate sexual compulsivity, the developers of this scale used the 80th percentile as their cut-point to ensure that compulsive individuals defined by them were at least one SD (standard deviation) above the mean on this scale [21]. The 85% percentile was defined as the cut-point in our study according to this method. The result obtained by using the categorical variable still failed to find a significant association between SC and UAI with regular sex partners while still finding evidence of association for the other partner types (general UAI and UAI with commercial sex partners). Given that the result may vary according to different cut-points and the cut-point may vary according to different samples, using the continuous variable may produce a more stable result.

Analyses indicated that highest educational level and monthly salary were significantly related to UAI; age was significantly related to UAI with regular sex partners; age, highest educational level, and self-reported sexual orientation were significantly related to UAI with non-regular sex partners; self-reported sexual orientation was significantly related to UAI with commercial sex partners. Participants with a higher educational level were less likely to perform UAI. This difference may result from the situation that participants with a lower educational level are less informed about HIV prevention knowledge in China [57]. Therefore, sex and HIV/AIDS-related education and research are urgently needed, not only to fill the knowledge gap in Chinese sex education but also to help mitigate social discrimination and stigma toward MSM [58].

The differences in the associations between sexual compulsivity and UAI with regular sex partners, UAI with non-regular sex partners, and UAI with commercial sex partners provide new insights into the reasons for different UAI and indicate the importance of differentiating between these practices in future research [41]. Continued research on the nature of sexual compulsivity may help to clarify the mechanism underlying UAI with non-regular and commercial sex partners. Sexual compulsivity represents sexual preoccupation and lack of sexual control, which is more likely to be associated with casual sexual interactions [32, 34]. This may be a result of a diminished ability to avoid sexual risk, as rational decision-making may be impaired under sexual arousal, making sexual risks less salient [59]. In other words, individuals who are sexually aroused may have a compromised capacity in perceiving specific risky sexual behaviors and avoid them. Therefore, individuals with a high level of sexual compulsivity may show a diminished long-term ability to avoid risky sexual behaviors, as such individuals experience prolonged states of sexual arousal [59]. However, although there is a relatively high prevalence rate of UAI with regular sex partners, it seems not to be a result of an impaired ability to avoid sexual risks. Crawford et al. (2006) reported that with regular partners who are HIV-seropositive, insertive UAI without ejaculation is much more frequent than receptive UAI with ejaculation, whereas with casual partners who are HIV-seropositive, insertive and receptive UAI practices occur almost as frequently [46]. Therefore, it is possible that individuals who practice UAI with regular sex partners are not unaware of the HIV risk. Previous studies on regular sex partners have suggested several important factors related to UAI with regular sex partners, including greater sexual impulsivity and concern about perceptions of mistrust between partners, intimacy interference, and syndemic stress [47, 60,61,62].

Thus, factors related to UAI should be considered in light of participants’ partner types, and HIV prevention strategies should be tailored to specific types of UAI, which is in line with previous research recommendations [41, 63]. For UAI with non-regular and commercial sex partners, therapy for sexual compulsivity may be effective to promote sexual health. Furthermore, providing condoms, communication, and behavior change can help to decrease UAI exposure [45]. Regarding UAI with regular sex partners, pre-exposure prophylaxis is a promising way to prevent HIV transmission among MSM individuals who are willing to practice condomless sex with partners to maintain intimacy [64]. However, a baseline survey for a clinical trial of PrEP in Shanghai indicated that the actual willingness of MSM to participate in the PrEP program is low [65]. At current circumstance in China, the implementation of PrEP is still challenging, and effective education to promote acceptance of PrEP is needed.

Several limitations of this study should be pointed out. First, caution is needed in drawing a causal conclusion, as this was a cross-sectional study. Second, the snowball sampling method may have caused selection bias, which might have affected the accuracy of the study conclusions; however, this sampling method is frequently used in studies targeting hard-to-reach populations. Additionally, social desirability may have affected the responses, as the questionnaire surveys were completed with the help of face-to-face interviews; participants thus may have been reluctant to provide honest answers. Finally, the HIV serostatus of participants and the type of sexual behavior (e.g., insertive or receptive) were not measured in this study.

Conclusions

Our study showed that the association between sexual compulsivity and UAI varies according to the type of UAI. Sexual compulsivity is not significantly associated with UAI with regular sex partners but is significantly associated with UAI with non-regular and commercial sex partners. Tailored cognitive–behavioral therapies targeting various types of UAI are urgently needed to optimize current HIV intervention programs.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- ORu:

-

Univariate odds ratio

- SCS:

-

Sexual Compulsivity Scale

- UAI:

-

Unprotected anal intercourse

References

Lu L, Jia M, Ma Y, Yang L, Chen Z, Ho DD, et al. The changing face of HIV in China. Nature. 2008;455(7213):609.

Ministry of Health of China, UNAIDS, WHO. 2005 HIV/AIDS epidemic and work progress of prevention and control in China. China: Beijing; 2006.

Ministry of Health of China, UNAIDS, WHO. 2009 estimates for the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China. China: Beijing; 2010.

Ministry of Health of China, UNAIDS, WHO. 2011 estimates for the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China. China: Beijing; 2011.

State Council AIDS Working Committee Office. UN theme group on AIDS in China. In: A joint assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in China (2007). Beijing, China; 2007.

Hei FX, Wang L, Qin QQ, Wang L, Guo W, Li DM, et al. Epidemic characteristics of HIV/AIDS among men who have sex with men from 2006 To 2010 in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2012. 33(1):67–70.

Hong S, Xu J, Han X, Li JS, Arledge KC, Zhang L. Bring safe sex to China. Nature. 2012;485(7400):576–7.

Zhong F, Lin P, Xu H, Wang Y, Wang M, et al. Possible increase in HIV and syphilis prevalence among men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China: results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1058–66.

Zablotska IB, Prestage G, Middleton M, Wilson D, Grulich AE. Contemporary HIV diagnoses trends in Australia can be predicted by trends in unprotected anal intercourse among gay men. AIDS. 2010;24:1955–8.

Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Walavalkar I, Chiasson MA. Crystal methamphetamine use predicts incident STD infection among men who have sex with men recruited online: a nested case-control study. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e41.

Li HM, Peng RR, Li J, Yin YP, Wang B, et al. HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in China: a meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23431.

Berry M, Wirtz AL, Janayeva A, Ragoza V, Terlikbayeva A, et al. Risk factors for HIV and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Almaty, Kazakhstan. PloS One. 2012;7:e43071.

Vu L, Andrinopoulos K, Tun W, Adebajo S. High levels of unprotected anal intercourse and never testing for HIV among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: evidence from a cross-sectional survey for the need for innovative approaches to HIV prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:659–65.

Carey JW, Mejia R, Bingham T, Ciesielski C, Gelaude D, Herbst JH, et al. Drug use, high-risk sex behaviors, and increased risk for recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chicago and Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1084–96.

Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, Kelly JA. Sexual sensation seeking: scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. J Pers Assess. 1994;62(3):385–97.

Wim VB, Christiana N, Marie L. Syndemic and other risk factors for unprotected anal intercourse among an online sample of Belgian HIV negative men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):50–8.

Lau JTF, Siah PC, Tsui HY. A study of the STD/AIDS related attitudes and behaviors of men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(4):367–73.

Zhao Y, Ma Y, Chen R, Li F, Xia Q, Hu Z. Non-disclosure of sexual orientation to parents associated with sexual risk behaviors among gay and bisexual MSM in China. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):193–203.

O'Leary A, Wolitski RJ, Remien RH, Woods WJ, Parsons JT, Moss S, et al. Psychosocial correlates of transmission risk behavior among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. Aids. 2005;19(suppl 1(19 Suppl 1)):S67–75.

Xu W, Zheng L, Yong L, Yong Z. Sexual sensation seeking, sexual compulsivity, and high-risk sexual behaviours among gay/bisexual men in Southwest China. AIDS Care. 2016;28(9):1138.

Benotsch EG, Kalichman SC, Kelly JA. Sexual compulsivity and substance use in hiv-seropositive men who have sex with men: prevalence and predictors of high-risk behaviors. Addict Behav. 1999;24(6):857.

Dodge B, Reece M, Cole SL, Sandfort TG. Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. J Sex Res. 2004;41(4):343–50.

Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(4):940.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):586.

Schnarrs PW, Rosenberger JG, Satinsky S, Brinegar E, Stowers J, Dodge B, et al. Sexual compulsivity, the internet, and sexual behaviors among men in a rural area of the United States. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(9):563–9.

Bancroft J. Sexual behavior that is “out of control”: a theoretical conceptual approach. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;31:593–601.

Black DW. Compulsive sexual behavior: a review. J Pract Psychol Behav Health. 1998;4:219–29.

Kafka MP, Prentky RA. Preliminary observations of DSM-III-R Axis I comorbidity in men with paraphilias and paraphilias-related disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:481–7.

Gold SN, Heffner CL. Sexual addiction: many conceptions, minimal data. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(3):367.

Quadland MC. Compulsive sexual behavior: definition of a problem and an approach to treatment. J Sex Marital Ther. 1985;11(2):121.

Quadland MC, Shattls WD. AIDS, sexuality, and sexual control. J Homosex. 1987;14(1–2):277.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale: further development and use with HIV-positive persons. J Personal Assess, 2001. 76(3):379.

Kalichman SC, Cain D. The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexually transmitted infection clinic. J Sex Res. 2004;41(3):235–41.

Kalichman SC, Greenberg J, Abel GG. HIV-seropositive men who engage in high-risk sexual behaviour: psychological characteristics and implications for prevention. AIDS Care. 1997;9(4):441–50.

McBride K, Reece M, Sanders SA. Using the sexual compulsivity scale to predict outcomes of sexual behavior in young adults. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2008;15:97–115.

Liao W, Lau JT, Tsui HY, Gu J, Wang Z. Relationship between sexual compulsivity and sexual risk behaviors among Chinese sexually active males. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(3):791–8.

Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, et al. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(5):817–26.

Dodge B, Reece M, Herbenick D, et al. Relations between sexually transmitted infection diagnosis and sexual compulsivity in a community-based sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(84):324–7.

Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2011;102(1):156.

Coleman E, Horvath KJ, Miner M, et al. Compulsive sexual behavior and risk for unsafe sex among internet using men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(5):1045–53.

Wang Z, Wu X, Lau J, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with unprotected anal intercourse with regular and nonregular male sexual partners among newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men in China. HIV Med. 2017;18(9):635–46.

Li X, Shi W, Li D, et al. Predictors of unprotected sex among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39(1):99–108.

Mor Z, Davidovich U, BessuduManor N, et al. High-risk behaviour in steady and in casual relationships among men who have sex with men in Israel. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(87):532–7.

Lim SH, Bazazi AR, Sim C, et al. High rates of unprotected anal intercourse with regular and casual partners and associated risk factors in a sample of ethnic Malay men who have sex with men (MSM) in Penang, Malaysia. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(8):642.

Wu J, Hu Y, Jia Y, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in China: an updated meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98366.

Crawford JM, Kippax SC, Mao L, et al. Number of risk acts by relationship status and partner Serostatus: findings from the HIM cohort of homosexually active men in Sydney, Australia. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):325–31.

Cai Y, Lau JT. Multi-dimensional factors associated with unprotected anal intercourse with regular partners among Chinese men who have sex with men in Hong Kong: a respondent-driven sampling survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):1–10.

Lau JT, Cai W, Tsui HY, Cheng J, Chen L, Choi KC, et al. Prevalence and correlates of unprotected anal intercourse among Hong Kong men who have sex with men traveling to Shenzhen, China. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1395–405.

Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. Aids. 2009;23(9):1153–62.

Gu J, Bai Y, Lau JT, et al. Social environmental factors and condom use among female injection drug users who are sex workers in China. Aids Behav. 2014;18(2):181–91.

Yan J, Lau JT, Tsui HY, Gu J, Wang Z. Prevalence and factors associated with condom use among Chinese monogamous female patients with sexually transmitted infection in Hong Kong. J Sex Med. 2012;9(12):3009–17.

Jin X, Smith K, Chen RY, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among male clients of female sex workers in Yunnan, China. Jaids. 2010;53(1):131–5.

Li J, Liu H, Li J, et al. Sexual transmissibility of HIV among opiate users with concurrent sexual partnerships: an egocentric network study in Yunnan, China. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1780–7.

Lau JT, Tsui HY, Cheng S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative efficacy of adding voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) to information dissemination in reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among Hong Kong male cross-border truck drivers. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):17–28.

Iacobucci D. Mediation analysis and categorical variables: the final frontier. J Consum Psychol. 2012;22(4):582–94.

Eric G, Benotsch SCK, Steven D. Pinkerton. Sexual compulsivity in HIV-positive men and women: prevalence, predictors, and consequences of high-risk behaviors. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2001;8(2):83–99.

Feng Y, Wu Z, Detels R, et al. HIV/STD prevalence among men who have sex with men in Chengdu, China and associated risk factors for HIV infection. Jaids. 2010;53(1):74–80.

Lau JT, Cai WD, Tsui HY, Chen L, Cheng JQ. Psychosocial factors in association with condom use during commercial sex among migrant male sex workers living in Shenzhen, mainland China who serve cross-border Hong Kong male clients. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):939–48.

Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, Long J. Sexual risk-taking in gay men: the relevance of sexual arousability, mood, and sensation seeking. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:555–72.

Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(2):177–86.

Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Neilands TB, Darbes LA. Relationship characteristics associated with sexual risk behavior among MSM in committed relationships. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(12):738.

Starks TJ, Tuck AN, Millar BM, Parsons JT. Linking Syndemic stress and behavioral indicators of main partner HIV transmission risk in gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(2):439–48.

Starks TJ, Millar BM, Parsons JT. Predictors of condom use with main and casual partners among HIV-positive men over 50. Health Psychol. 2015;

Centers for Disease Control (USA). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

Ding Y, Yan H, Ning Z, et al. Low willingness and actual uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among men who have sex with men in shanghai, China. Biosci Trends. 2016;10(2):113.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants for their contribution. We thank the Shanghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Shanghai Dermatology Hospital, and the Shanghai Youth AIDS Health Promotion Centre for helping us to organize the survey.

We thank Diane Williams, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (14YS022), the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (14XJ10007), the Cross-study Research Foundation about Medicine and Engineering of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2014QN23), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71603166, 71673187), the Shanghai Pujiang Program (14PJC076), the 2016 Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Public Health-SCDC Research Cooperation Fund, the Social Cognitive and Behavioral Sciences program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (14JCRY03), the Natural Sience Foundation of China Young Scientist Fund (81703278), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (APP1092621), and the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201811071). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, and data will not be shared because of some sensitive information contained in it and of the agreement with the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YC, YW, XW, and other authors discussed, conceived, and designed the study. ZZW and XQJ performed the data collection and were involved in data analysis. XW, GX, and YC analyzed the data with suggestions from other authors. HZ and RL contributed to the critical revision. XW, ZZW, and XQJ wrote the paper. GX, XW, HZ, and YC contributed substantially to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was provided by the School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Written consent was obtained from the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Wang, Z., Jiang, X. et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between sexual compulsivity and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in shanghai, China. BMC Infect Dis 18, 465 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3360-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3360-x