Abstract

Background and objective

Studies focusing on pulmonary tuberculosis in advanced age (≥80 years) are lacking. This study aimed to explore treatment delay, outcomes and their predictors in this group.

Methods

Adult (≥20 years) patients with pulmonary tuberculosis were identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan from 2004 to 2009. Treatment completion and mortality rates were noted at one year after treatment.

Results

Among the 81,081 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis identified, 13,923 (17.2%) were aged ≥80 years, and 26,897 (33.2%) were aged 65–79 years. The treatment completion, mortality rates and treatment delay were 54.8%, 34.7% and 61 (12–128) [median, (1st-3rd quartiles)] days in patients aged ≥80 years, 68.3%, 18.5% and 53 (8–122) days in patients aged 65–79 years, and 78.9%, 6.5% and 21 (1–84) days in patients aged <65 years, respectively. The elder patients were more likely to receive second-line anti-tuberculosis agents. The treatment completion rate decreased with older age, female sex, comorbidities, low income, requiring second-line anti-tuberculosis agents, severity of pulmonary tuberculosis and longer treatment delay. Older age, female sex, comorbidities, low income, and not undergoing rapid molecular diagnostic tests were independently associated with longer treatment delays.

Conclusions

Pulmonary tuberculosis in advanced age has a longer treatment delay and a higher mortality rate. Applying rapid molecular diagnostic tools may reduce treatment delay and should be integrated into the diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary tuberculosis, particularly in elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Because of increasing life expectancy and declining birth rates, the ageing population problem has become a critical worldwide public health concern, particularly in developed countries [1]. Dysfunction in cellular immunity caused by chronic comorbidities, malnutrition, and age-related changes can render elderly people more susceptible to infectious agents, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis [2, 3]. In 2015, 10.4 million people were diagnosed as active tuberculosis (TB) and among them, 1.8 million died [4]. In industrialised societies, the trend of institutionalised care further exposes elderly patients to a higher risk of TB infection. The elderly population therefore represents a large reservoir of TB infection. In developing countries, TB continues to affect all susceptible individuals, including elderly adults [5].

Delay in initiation of anti-TB treatment is a major impediment to effective control of TB [6]. However, in elderly people, the clinical presentations of TB can be myriad and easily confused with other age-related illnesses [7]. Although the standard four-combined anti-TB treatment is highly effective, it is associated with a high pill burden, long treatment course, and severe drug-related adverse events. Elderly patients are more prone to experience adverse events such as severe hepatotoxicity during anti-TB treatment [8]. These factors result in a unique challenge and suboptimal outcomes in management of TB among the geriatric population.

Sputum smear microscopy remains the most common method for diagnosing pulmonary TB (PTB), but smear-positive TB accounted for only 56% of all notified new TB cases [4]. A mycobacterial culture, although more sensitive, requires an average of 9.7 and 20.2 days to detect M. tuberculosis in liquid and solid culture media, respectively [9]. The advent of rapid molecular diagnostic tools, which are sensitive, specific, and quick, provides new opportunities to facilitate the microbiological diagnosis of PTB [10, 11].

In this nationwide retrospective cohort study, we investigated the impact of advanced age (≥80) on delay and outcome of anti-TB treatment with an emphasis on the influence of rapid molecular diagnostic tools.

Methods

The National Health Insurance (NHI) programme of Taiwan is a compulsory insurance system covering 99.6% of the national population with a benefit package including comprehensive inpatient and outpatient medical services. The claims data were collected systemically and de-identified before being released for research purposes. The data were issued by the National Health Research Institute with delegation of authority from the Ministry of Health and Welfare under license for the current study.

In this study, patients with PTB during 2004–2009 were selected from the NHI Research Database (NHIRD) and followed-up until death or 31st December 2010, whichever came first. The Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital approved the study (NTUH REC: 201,309,064 W).

Selection criteria for pulmonary tuberculosis

PTB was defined as having at least two outpatient visits or any inpatient record with compatible diagnoses of PTB (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 010–012, 018) [12, 13]. Participants needed to have been prescribed at least two anti-TB drugs simultaneously for ≥120 days within a period of 180 days as well as at least one prescription of ≥3 anti-TB drugs. Patients were also considered to have PTB if they had a positive TB culture or received ≥2 anti-TB drugs simultaneously for ≥30 days during the last 3 months before loss to follow-up [13]. Patients who were diagnosed with non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection (ICD-9-CM code 031) during the last 2 months of anti-TB treatment were excluded. The annual number of PTB cases identified with abovementioned criteria has been verified with that reported from the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control [12, 13].

Treatment outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis

The index date was defined as the date when anti-TB treatment began. For those who did not receive anti-TB treatment, the index date was defined as the date of death. The first-line anti-TB agents included isoniazid, rifampicin/rifabutin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. The second-line anti-TB agents included quinolones, aminoglycosides, prothionamide, cycloserine, terizidone and para-aminosalicyclic acid. Treatment outcome was recorded 1 year after the index date. Anti-TB treatment was traced until the last prescription comprising two or more anti-TB drugs followed by no further anti-TB agents in the subsequent 60 days. Anti-TB treatment was considered completed for those who remained alive at the end of anti-TB treatment and received ≥144 days of rifamycin (a corresponding adherence ≥80% of 180 days) and a total treatment duration ≤365 days. Mortality was recorded if death occurred within 365 days and before the anti-TB treatment was completed [14].

Anti-tuberculosis treatment delay

Treatment delay was calculated as the interval from the earliest date fulfilling any two events possibly indicating the onset of PTB to the index date (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Events possibly indicating the onset of PTB included: diagnoses of TB or pneumonia (ICD-9-CM code 480–486 or 507), consulting pulmonologists or infectious disease specialists, receiving chest radiography, taking airway medications or antibiotics, and requiring a mycobacterial culture or M. tuberculosis–nucleic acid amplification test (MTB–NAAT) within 6 months prior to the index date. Airway medications included oral antitussives, mucolytic agents, and sympathomimetics. Antibiotics included penicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, carbapenems, and macrolides. The treatment delay was further decomposed into two parts. Delay in arousing clinical suspicion was defined as delay prior to the date first mycobacterial culture study was prescribed. Delay due to technical limitation in diagnosis was the interval from first mycobacterial culture study to the start of anti-TB treatment.

Possible confounding factors

Underlying comorbidities that have been shown to interfere with the treatment outcomes and delays were recorded at the index date [12, 13, 15]. The low-income group was identified from the insurance status and required the annual household income to be below 4500 US dollars [16].

Baseline TB severity was assessed by the presence of extra-pulmonary TB (diagnostic code of ICD-9-CM codes 012.0, 013 ~ 018), requiring second-line anti-TB agents and the requirement of hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilatory support during the first 14 days of anti-TB treatment [15].

The healthcare system factors of initial medical visits indicating PTB onset, including hospital accreditation level, specialty and location, were recorded. The location was classified as an urban (population density ≥ 1500 people/km2) or rural area.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as either the median (first to third quartiles) or number (%). Intergroup differences were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for numerical variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis, including age, sex, comorbidities, low-income status, baseline TB severity, healthcare system factors, and treatment delay, was applied to identify the independent predictors of anti-TB treatment completion within 1 year. Factors influencing the length of treatment delay were evaluated using multivariate linear regression analysis. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Subpopulation and sensitivity analyses

Subpopulation analyses were performed to investigate the impact of the MTB–NAAT on treatment delay in three subgroups: (i) patients with age ≥ 65 years; (ii) patients with age ≥ 80 years; and (iii) patients whose delay due to technical limitation longer than 7 days, implying that they were smear-negative PTB cases.

A sensitivity analysis was performed by adopting a stricter definition for treatment delay, which was calculated as the interval between the earliest date fulfilling any three events possibly indicating the onset of PTB and the index date.

Results

From the nationwide database, 81,081 adult patients with PTB were identified (Fig. 1). Among them, 3747 (4.6%) died before anti-TB treatment began. The median age was 65.2 (47.5–76.9) years, with a male–female ratio of 2.25. The incidence rate of PTB was exponentially correlated to the age (R 2 = 0.962; Fig. 2).

The clinical characteristics and treatment courses are summarised in Table 1. More PTB cases were ≥80 years after 2006 than those before, reflecting the trend of ageing. The most common underlying comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (28.4%), malignancy (8.7%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8.2%). Compared with patients 65–79 years of age, patients with age ≥ 80 years had generally lower prevalences of comorbidities except for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis was more common among younger patients. Computerised tomography (CT) scan was performed more frequently among older patients (age of 65 years or more). Invasive diagnostic procedures such as bronchoscopy and CT-guided biopsy were done more frequently among patients 65–79 years of age and less common among patients with age ≥ 80 years.

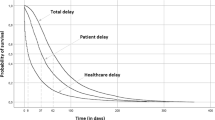

The elder patients required more outpatient visits, emergency room visits, admissions, chest x ray, mycobacterial culture, and MTB-NAAT studies to confirm the TB diagnosis and to start the anti-TB treatment (Additional file 1: Table S3). Among the ageing population, the duration of anti-TB treatment as well as duration covered by each first-line anti-TB drug was shorter while second-line anti-TB drugs were prescribed more frequently; indicating regimen modification. The elder patients had higher baseline disease severity reflected by the higher probabilities of requiring hospitalisation, intensive care, and mechanical ventilatory support during the first 14 days of anti-TB treatment, and consumed more medical resources during the anti-TB treatment course. However, the elder patients carried a lower treatment completion rate and a higher mortality rate (Fig. 3, Table 1). Female patients were younger, had less comorbidities, and a lower mortality rates than male patients (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Additional file 1: Table S2 summarises specific events that indicated the PTB onset. The prescription of airway medications or antibiotics tended to occur much earlier than chest x ray examination as well as mycobacterial study in the clinical course. The treatment delay was longer among the elderly than that among younger patients (Fig. 2). A later TB diagnosis year was associated with a shorter treatment delay in all age groups (P < 0.001) except for patients ≥80 years old (P = 0.678). The treatment delay was longer among patients with a fatal outcome (71 [11–139] days, Fig. 4) than those who completed treatment (33 [4–99] days) (P < 0.001)

The overall treatment completion rate within 1 year was 71.2%. Multivariate logistic regression showed an association of lower treatment complete rate with age and longer treatment delay, after adjusting the effect of sex, co-morbidities, healthcare system factors of initial visits, baseline TB severity, and use of second-line anti-TB agents (Table 2).

The median treatment delay was 37 (4–107) days. The length of delay increased with age, comorbidities, low-income status, and initially seeking medical help in an urban area (Table 3). Men (coefficient − 6.81 [−7.68 , −5.95]) and performing an MTB–NAAT (coefficient − 2.20 [−3.51, −0.90]) were independently associated with a shorter treatment delay.

Subpopulation analyses illustrated a stronger impact of performing MTB–NAAT on the treatment delay among the elderly patients (coefficient − 3.97 [−7.09, −0.84]) and smear-negative PTB (coefficient − 4.35 [−6.14, −2.55]) (Additional file 1: Table S4). In the sensitivity analysis adopting a stricter definition of treatment delay, the results were consistent with those in the main scenario (Additional file 1: Tables S5-S6, Table 3).

Discussion

The present study is the first nationwide report on the outcome of anti-TB treatment in advanced age. It has three crucial findings. First, the incidence rate of PTB is exponentially correlated with the age that elderly adults are the major reservoir of PTB infections in Taiwan. Second, although the anti-TB treatment completion rate has increased following the implementation of directly observed treatment, short course (DOTS) programme in Taiwan since 2006, elder patients with PTB remained to have longer treatment delays and worse outcomes, particularly those with underlying comorbidities. Third, the length of treatment delay is inversely correlated with the treatment completion rate. The treatment delay can be shortened by applying rapid molecular diagnostic tools such as the MTB–NAAT. The extent of benefit is even greater among the elder patients and those with smear-negative PTB. Given the increasing elderly populations worldwide, the findings of the present study can serve as a reference for policies regarding TB care.

According to a World Health Organization report, the TB notification rate increases with age worldwide [4]. As a result of population ageing, the proportion of elder TB patients increased steadily from 1990 to 2015 [17]. The gradual deterioration of the immune system (involving both the host’s capacity to respond to infections and the development of long-term immune memory as age increases, referred to as immunosenescence) may be the major contributor [18, 19]. Other factors, such as malnutrition, poverty, decreased access to health services, comorbidities, and iatrogenic immunosuppression, also contribute to the higher risk of infection in ageing populations [20,21,22]. However, the correlation between age and PTB incidence has never been calculated, and reports on advanced aged population are currently lacking. This is the first study showing that the risk of PTB not only increases but is exponentially correlated with age (R 2 = 0.962; Fig. 2).

Because of the high prevalence of underlying comorbidities, anti-TB treatment in elderly patients is frequently complicated by drug–drug interaction and adverse drug reactions, leading to an increased rates of regimen modification and default [8, 23]. Consequently, advanced age increases the mortality rate of TB significantly and eclipses the treatment completion rate [23,24,25,26,27]. In this study, the treatment completion rate among patients ≥65 years old was comparable to the two previous reports (71%–73%) [25, 26]. An even lower treatment completion rate was demonstrated among those with age ≥ 80 years.

Another crucial contributor to poor outcomes in elderly patients with PTB is the delay in anti-TB treatment. The clinical symptoms and radiographic findings of PTB in elderly people tend to be less specific [25, 28, 29]. Extrapulmonary TB including TB meningitis, osteomyelitis or urological involvement is more common with advancing age [3]. Combined with decreased access to health services [30], the atypical manifestations of TB in elder people result in a delay in the diagnosis and treatment [24, 28, 29]. As shown in the present study, prescription of airway medications and antibiotics occurred early in the course prior to chest x ray examination as well as the diagnosis of PTB, suggesting that these cases are already symptomatic and may be infectious in the community and health care system for a long period. Moreover, even when chest radiography is ordered, the duration of treatment delay is still far from negligible, indicating that a high proportion of patients presented with non-diagnostic radiographic findings, particularly in elderly patients. Consistent with previous studies, treatment delay increases mortality rates in patients with PTB [31, 32].

A treatment delay may result from either a delay in seeking health service (patient delay) or failure in establishing diagnosis and starting treatment (provider delay) [6, 33]. In countries with a high TB burden, insufficient patients’ awareness for the TB disease and financial barrier are major contributors for delay in diagnosis [6]. In countries with a low TB burden, the percentage of advanced pulmonary TB with positive sputum smear and cavitary lesions steadily increased due to declining clinicians’ vigilance to the presentations of TB and a lack of efficient diagnostic tools to diagnose TB in its early stage [34, 35]. Because of the built-in shortage of claims data, patient delay cannot be accessed in this study. However, the median of provider delay among patients aged 65–79 years was 32 days longer than that among those aged <65 years (53 vs 21 days). For those aged ≥80 years, the impact can be higher since the treatment delay is longer. In addition to the negative impact on treatment outcome, failure to recognise active PTB cases increases the risk of transmission [36], thus constituting a major hindrance to effective control for TB.

Because ageing is a well-known risk factor for adverse events during anti-TB treatment [8, 23, 37], for safety concerns, physicians are becoming increasingly hesitant to initiate anti-TB treatment unless solid bacteriologic evidence exists. Furthermore, because of the improved accessibility of health services in Taiwan, patients tend to seek medical help while their disease is minimal. This probably explains why an initial medical visit in an urban area is associated with a longer treatment delay than in a rural area. Implementing MTB–NAAT was shown to reduce treatment delay (Table 3), especially among the elderly and smear-negative PTB cases. These findings support the implementation of a rapid molecular assay for PTB diagnosis.

Most patient factors leading to treatment non-adherence can be eliminated with supervision, resulting in an improved treatment completion rate and reduction in unfavourable outcomes [38]. Under Taiwan’s national TB programme, DOTS has been implemented countrywide since 2006. The findings of this study support the continuous government commitment to TB control and the necessity of continuing DOTS programme in Taiwan.

The present study has some limitations. First, because of the built-in shortage of claims data, the results of mycobacterial studies and radiographic findings were unavailable. Second, the disease severity, a critical determinant of patient outcome, was not known. Although hospitalisation and admission to intensive care unit were used as surrogates of disease severity in this study, they may not correlate 100%. Third, the impact of the MTB–NAAT on treatment delay may be confounded by the indication, resulting in an overestimation of it benefits. Lastly and importantly, though the overall delay was calculated by fulfilling two or more events indicating TB onset, they could be due to clinical conditions other than TB. However, it may not be a considerable bias since sensitivity tests showed that the model was consistent across the broader or stricter definitions of delay in treatment.

Conclusions

The incidence of PTB increased exponentially with age. Ageing is associated with unfavourable outcomes and longer treatment delay, particularly for those with underlying comorbidities. Rapid molecular diagnostic tools can shorten treatment delay and should be integrated in the diagnostic algorithm for PTB, particularly in patients with advanced age.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computerised tomography

- DOTS:

-

Directly observed treatment, short course

- ICD-9-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- MTB-NAAT:

-

M. tuberculosis–nucleic acid amplification test

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD:

-

National Health Insurance Research Database

- PTB:

-

Pulmonary tuberculosis

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs.: the world ageing situation: exploring a society for all ages. New York: United Nations; 2001.

Haq K, McElhaney JE. Ageing and respiratory infections: the airway of ageing. Immunol Lett. 2014;

Byng-Maddick R, Noursadeghi M. Does tuberculosis threaten our ageing populations? BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:119.

WHO: Global Tuberculosis Report 2016. In. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2016.

Rajagopalan S. Tuberculosis and aging: a global health problem. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(7):1034–9.

Li Y, Ehiri J, Tang S, Li D, Bian Y, Lin H, et al. Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:156.

Yoshikawa TT. Tuberculosis in aging adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(2):178–87.

Shu CC, Lee CH, Lee MC, Wang JY, Yu CJ, Lee LN. Hepatotoxicity due to first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs: a five-year experience in a Taiwan medical centre. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(7):934–9.

Pfyffer GE, Welscher HM, Kissling P, Cieslak C, Casal MJ, Gutierrez J, et al. Comparison of the mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT) with radiometric and solid culture for recovery of acid-fast bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(2):364–8.

Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, Nicol MP, Shenai S, Krapp F, et al. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(11):1005–15.

Kivihya-Ndugga L, van Cleeff M, Juma E, Kimwomi J, Githui W, Oskam L, et al. Comparison of PCR with the routine procedure for diagnosis of tuberculosis in a population with high prevalences of tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1012–5.

Wang JY, Lee MC, Shu CC, Lee CH, Lee LN, Chao KM, et al. Optimal duration of anti-TB treatment in patients with diabetes: nine or six months? Chest. 2015;147(2):520–8.

Wang JY, Lee CH, Yu MC, Lee MC, Lee LN, Wang JT. Fluoroquinolone use delays tuberculosis treatment despite immediate mycobacteriology study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(2):567–70.

WHO: Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis – 2013 revision. In.; 2014: 40.

Wang JY, Lee MC, Chang JH, Yu MC, Wu VC, Huang KL, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification tests reduce nosocomial tuberculosis exposure in intensive care units: a nationwide cohort study. Respirology. 2015;20(8):1233–40.

Public Assistance Act. In., 7th edn. Taipei, Taiwan (R.O.C): Ministry of the Interior; 2010.

Li J, Nishikiori N, Leung CC, Yeoh E, Chung P. Is population ageing cancelling out progress made in tuberculosis control in Hong Kong special administrative region SAR (China)? Age-adjusted analysis of case notification data, 1990-2015. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2017;8(1):33–6.

Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007;120(4):435–46.

Cuervo AM, Macian F. Autophagy and the immune function in aging. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;29:97–104.

Akinosoglou KS, Karkoulias K, Marangos M. Infectious complications in patients with lung cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(1):8–18.

Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Socioeconomic differentials in immune response. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):902–8.

Lee CH, Lee MC, Shu CC, Lim CS, Wang JY, Lee LN, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with chronic obstructive airway disease in Taiwan: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:194.

Teale C, Goldman JM, Pearson SB. The association of age with the presentation and outcome of tuberculosis: a five-year survey. Age Ageing. 1993;22(4):289–93.

Cruz-Hervert LP, Garcia-Garcia L, Ferreyra-Reyes L, Bobadilla-del-Valle M, Cano-Arellano B, Canizales-Quintero S, et al. Tuberculosis in ageing: high rates, complex diagnosis and poor clinical outcomes. Age Ageing. 2012;41(4):488–95.

Leung CC, Yew WW, Chan CK, Chau CH, Tam CM, Lam CW, et al. Tuberculosis in older people: a retrospective and comparative study from Hong Kong. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(7):1219–26.

Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare of Japan: Tuberculosis surveillance annual report 2007. In.: Tokyo: Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association; 2007.

Yen YF, Feng JY, Pan SW, Chuang PH, Su VY, Su WJ. Determinants of mortality in elderly patients with tuberculosis: a population-based follow-up study. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(7):1374–81.

Chan CH, Woo J, Or KK, Chan RC, Cheung W. The effect of age on the presentation of patients with tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76(4):290–4.

Liaw YS, Yang PC, Yu CJ, Wu ZG, Chang DB, Lee LN, et al. Clinical spectrum of tuberculosis in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(3):256–60.

Cheng G, Tolhurst R, Li RZ, Meng QY, Tang S. Factors affecting delays in tuberculosis diagnosis in rural China: a case study in four counties in Shandong Province. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99(5):355–62.

Wang JY, Hsueh PR, Jan IS, Lee LN, Liaw YS, Yang PC, et al. Empirical treatment with a fluoroquinolone delays the treatment for tuberculosis and is associated with a poor prognosis in endemic areas. Thorax. 2006;61(10):903–8.

Wang JY, Hsueh PR, Wang SK, Jan IS, Lee LN, Liaw YS, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis: a 10-year experience in a medical center. Medicine. 2007;86(1):39–46.

Ngadaya ES, Mfinanga GS, Wandwalo ER, Morkve O. Delay in tuberculosis case detection in Pwani region, Tanzania A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:196.

Wallace RM, Kammerer JS, Iademarco MF, Althomsons SP, Winston CA, Navin TR. Increasing proportions of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis reported in the United States: are delays in diagnosis on the rise? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(10):1016–22.

Dale KD, Tay EL, Trauer JM, Trevan PG, Denholm JT. Comparing tuberculosis management under public and private healthcare providers: Victoria, Australia, 2002-2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):324.

Greenaway C, Menzies D, Fanning A, Grewal R, Yuan L, FitzGerald JM. Canadian collaborative group in nosocomial transmission of T: delay in diagnosis among hospitalized patients with active tuberculosis--predictors and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(7):927–33.

Rajagopalan S. Tuberculosis in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(3):479–91.

Weis SE, Slocum PC, Blais FX, King B, Nunn M, Matney GB, et al. The effect of directly observed therapy on the rates of drug resistance and relapse in tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(17):1179–84.

Acknowledgements

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the of National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan and managed by National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan or National Health Research Institutes.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan [grant number NSC-101-3114-Y-002-003]; the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan [grant number MOHW-105-CDC-C-114-000103]; and Wanfang Hospital [grant number 105swf10].

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Health Research Institute but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of National Health Research Institute.

Authors’ contributions

CHL, JYW, LNL, and KJB designed the study. CHL and PYL involved in data acquisition. CH L, PYL, JYW, HCL, JHC, and CCL were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. CHL, JYW, and KJB drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the draft and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The present study contains no personal information of individual subjects.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital approved the study (NTUH REC: 201,309,064 W).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplemental data for “Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Advanced Age”. The file contains the schematic diagram for delay calculation, the clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, treatment delay in pulmonary tuberculosis, medical resource utilisation, subpopulation analyses, and sensitivity analyses (PDF 1066 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CH., Wang, JY., Lin, HC. et al. Treatment delay and fatal outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis in advanced age: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 17, 449 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2554-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2554-y