Abstract

Background

This is the first report of anisakiasis in a Croatian patient, evidenced from an archival paraffin-embedded and hematoxylin-eosin stained tissue section. Anisakiasis has been only suspected in the country based on previously detected anti-Anisakis IgE seroprevalence in the healthy coastal population, as well as an acute case where pathohistological and serological findings suggested the diseases, but the migrating larva has not been retrieved.

Case presentation

Seventy years-old female, operated in 1998 for pulmonary carcinoma, was admitted to the General hospital Šibenik, Croatia in 2003, because of gastric pain and nausea that lasted for couple of days. She was showing good general condition, full mobility and lucidity, subfebrile status. Abdominal palpation inferred acute pain in paraumbilical and ileocecal region. Exploratory right pararectal laparotomy revealed a hardened, 5 cm-long structure, located intraluminally in the sigmoid colon, not perforating colon serosa. The process has been dissected and sent for patohistological diagnosis. Results showed a 2 mm-long whitish nematode spiralised in muscular layer of colon mucosa surrounded by granulomatous inflammation.

Conclusion

After genomic DNA isolation of the nematode from the histological section, and amplification at the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 2 locus, etiological agent has been identified as Anisakis pegreffii. Used methodology suggests that screening of archival suspicious sections is feasible in order to study epidemiology of this zoonotic disease poorly recognised in Croatia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The genus Anisakis comprises parasites with an indirect generalist character [1] and an infective third-stage larvae (L3) that is commonly found in the viscera and musculature of many teleost species [2]. Post-mortem in fish, larvae tend to migrate from the abdominal cavity where the majority is spiralised intra vita, into fish flesh, where they are consequently difficult to detect at plain visual inspection [3]. It has been accepted that in humans, members of the nematode family Anisakidae cause a zoonotic disease anisakidosis, whereas anisakiasis is caused by members of the genus Anisakis [4]. Within genus Anisakis, two sibling species, A. pegreffii and A. simplex sensu stricto, are recognised as human pathogens in Europe and Japan [5, 6]. Although the first report of anisakiasis dates back to 1960 in Netherlands [7], an increase in Anisakis infection rate in human population has been observed nowadays, declaring anisakiasis as one of the most significant emerging food-borne diseases [8–18].

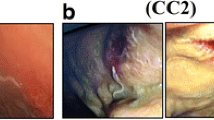

Paraffin-embedded section of the dissected patient colon showing degenerated body of the spiralised nematode (black arrowheads) and intensive eosinophilic infiltration (ei). Scale bar: 100 μm, magnification: 40x. Insert: Note the deterioration of the nematode cuticle (arrowhead). Scale bar 20 μm, magnification: 100x. H&E stained

The reasons range from purely ecological, as a more stringent conservation measures of protection of sea mammals as parasite’s final hosts, help increasing their populations and consequently that of their parasite [19]; to socio-cultural, as an ingression of “exotic” gastronomic habits throughout Europe [20]. The later includes consumption of thermally unprocessed or lightly processed traditional seafood like sushi and sashimi in Japan [21], tuna or sparid carpaccio, marinated, salted or pickled anchovy in Mediterranean [22–24], smoked or fermented herrings (maatjes) in Netherlands [25], dry cured salmon (gravlax) in Norway, raw salmon (lomi lomi) in Hawaii or ceviche in South America [26]. Finally, elevated medical consciousness to the disease and more detailed clinical examinations have enhanced the number of diagnosed cases in humans [27], although anisakiasis is still a misdiagnosed and underestimated entity in the Mediterranean.

Anisakis L3 larvae can enter human gastrointestinal tract at different sites of infection after ingestion of contaminated seafood, eliciting gastric, intestinal or ectopic anisakiasis [28]. Gastric anisakiasis is characterized by epigastric pain, nausea and vomits after a short period of 1–12 h postingestion of live Anisakis larvae [1], while in the intestinal form, abdominal pain is also the predominant symptom, but the incubation period may be delayed until 48–72 h, sometimes 5–7 days postingestion [29]. Ectopic anisakiasis relates to migration of the infective larvae through body cavities. Additionally, gastroallergic anisakiasis is another clinical form expressed in a relevant number of patients with gastric anisakiasis that have associated allergic symptoms, ranging from urticaria to anaphylactic shock [30–32]. Since allergic symptoms may predominate over gastrointestinal manifestations and most Anisakis infections are subclinical [22, 33], this condition can only be detected using immunological tests [34]. The quantity of cases with allergic aspects of Anisakis infections over Europe [23, 27, 34–36], urged recommending to carry out serological studies in populations at risk, both healthy or with food allergies in anamnesis, to understand the relevance of Anisakis infections in Europe [37, 38]. In south coastal part of the Adriatic Sea, Croatian population traditionally consumes home-made thermally unprocessed fish, mostly pickled, marinated, salted anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) and sardine (Sardina pilchardus) and the recent epidemiological study of seroprevalence of anti-Anisakis IgE showed that the sensitisation reached 3.5 % in the islands’ population or 2 % in the overall tested population [39]. All Anisakis positive subjects were high fish consumers, mostly of raw and home-made thermally unprocessed fish prepared in the traditional manner. Most of them reported professional or hobby occupational contact with fishery or fish industry. Contradictory to the anti-Anisakis IgE seroprevalence in Croatian costal population, no firm medical cases reporting the larva from patients have been so far evidenced in Croatia. The aim of this case report was to identify nematode larva from archival paraffin sections of a suspected case of anisakiasis using molecular tools.

Case presentation

Seventy years-old female, operated in 1998 for pulmonary carcinoma, was admitted to the General hospital Šibenik, Croatia in 2003, because of gastric pain and nausea that lasted for couple of days. She was showing good general condition, full mobility and lucidity, subfebrile status. Abdominal palpation inferred acute pain in paraumbilical and ileocecal region. Exploratory right pararectal laparotomy revealed a hardened, 5 cm-long structure, located intraluminally in the sigmoid colon, not perforating colon serosa. In general, colon showed to be thicker on palpation, without additional processes visible by inspection. The process has been dissected and sent for patohistological diagnosis (PHD) that evidenced a 2 mm-long whitish nematode spiralised in muscular layer of colon mucosa surrounded by granulomatous inflammation, suspected as a member of Anisakis. PHD was done after dehydrating, paraffin-embedding, cutting sections of 5 μm thickness and hematoxylin-eosin staining of the dissected process. Granulomatous change was not encapsulated by connective tissue nor calcified, and lacked the necrotic central area, indicating an acute process. Section through intramural process revealed two asymmetrical segments of the spiralised nematode in developed state of decomposition, surrounded by eosinophils and other leukocytic cells that perforated nematode cuticle and infiltrated its polymyarian muscle cells (Fig. 1). Decomposition of the inner nematode parts did not permit to identify its hallmark structures (absence of the ventricular appendix and intestinal caecum), disabling morphological identification of the nematode.

For purpose of the molecular identification of paraffin-embedded nematode, nematode were dissected from the slides to obtain its largest area. From those sections, genomic DNA was isolated using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany), for purification of genomic DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Genomic DNA from histological sections was amplified, purified, and the mitochondrial cox2 locus (~645 bp) was sequenced, as described previously [40]. Obtained sequence was uploaded in the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and a nucleotide database using a nucleotide query was done by default parameters (database Other, Optimize for Highly similar sequences (megablast), algorithm parameters: default). Unambiguous sequence of the mitochondrial cox2 gene (stored in GenBank under accession number KU057355) revealed that the unidentified nematode from the archival paraffin-embedded and hematoxylin-eosin stained histological section belongs to Anisakis pegreffii. Distribution of 100 BLAST hits on the query sequence gave maximum and total score of 1085, query cover of 89 %, E value 0.0 and 100 % identity to Anisakis pegreffii haplotype isolated from the Adriatic Sea (KC479875).

Our results represent the first molecular confirmation of the infective A. pegreffii larvae from the Croatian patient that presented an acute form of intestinal anisakidosis, identified in the archival hematoxylin-eosin stained histological section of the colon. Compared to Japan and United States [4], in the Mediterranean part of Europe there is still a scarce number of reported cases of clinical anisakiasis in contrast to the significant levels of parasitation that have been observed in some of the most economically important fish species consumed in this area as thermally insufficiently processed [41–45]. In a detailed study of evaluation of the Anisakis risk management in the Europe, [46] estimated anisakiasis incidence of 0.038 %, averaging to 20 cases per country per year. However, epidemiological data are scattered and occasionally reported for the Mediterranean basin.

In Italy, 54 cases reported in a 5 year period (1996–2011) [46] were associated with thermally unprocessed anchovies, herring and mackerel [46–48]. Among those showing acute gastrointestinal form, usually only eosinophilic granuloma associated with larvae is observed [49], while larva itself is isolated on rare occasions [50–52]. In Spain, while the allergic aspects of Anisakis infections have been extensively studied resulting in hundreds of cases of allergy reported since 1995 [27, 31, 53], less information is available on acute anisakiasis. For comparison, till 1999 in Spain 9 acute cases were described [54]; in 1997 96 cases of gastroallergic anisakiasis were diagnosed in patients in Madrid [55]; while from 1999–2003, in total 65 acute cases were reported [56, 57]. Moreover, while individual accidental anisakiasis is more frequent in Europe, three massive outbreaks have been described in Spain [58–60]. In France another massive infection was reported in 6 people after consumption of raw herring. In period between 1985–1987, 21 cases were confirmed by parasitological identification and ten years later, number increased to 80 cases [61, 62]. No official records exist for other countries in the Mediterranean basin, but in general anisakiasis can be considered as an reemerging, misdiagnosed and underestimated zoonosis.

Epidemiological situation in Croatia is even less clear. A recent epidemiological study that encompassed asymptomatic rural inland, urban and island population in Mid and South Dalmatia (South-East Croatia), revealed 2 % seroprevalence [39], which is less than in Spain, Italy and Morocco [23, 62–64] and higher than in Norway [65]. Differences could be a consequence of study design (e.g. Croatian asymptomatic vs. symptomatic populations in other countries), sensitivity of the method used [34, 65, 66], as well as fish consumption per capita in each of these countries, being fairly low in Croatia (8.5 kg/year per capita; [67]). Nevertheless, the presence of circulating anti-Anisakis IgE in the high-risk asymptomatic coastal population, indicates that in past the population was in contact with the live larva, but the lack of anisakiasis reports further suggests that the diseases in Croatia is underestimated. Recently, a case report describing a small intestine obstruction in a 14-year-old boy was suspected as enteric anisakiasis [68]. Anamnestic data included consumption of sushi and onset of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting 3 days later. After emergency laparotomy, inflammation and edematous changes of the terminal ileum, and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes were observed. Histopathological analysis revealed edema and diffuse infiltration of eosinophils in muscular layer and serosa of the appendiceal wall, but no parasites at the inflammation site or in process of migration. Specific anti-Anisakis IgE levels were significantly increased, although authors did not report the serological test deployed or its sensitivity. Considering the absence of morphological or molecular identification of the parasite in mentioned case, as well as the possibility of false Anisakis-positivity of some accepted serological tests [68], much evidence is missing to relate the etiological agent to Anisakis.

Conclusions

A. pegreffii identified from archival histopathological microscopic slides taken in 2003, morphologically could not be distinguished due to advanced processes of larval degradation. One of the main histopathological features of the local inflammatory lesions produced by infective larvae is intensive eosinophilic infiltration in the tissues surrounding the parasite, but seemingly, immune cells adherent to the larval epicuticle can not damage the nematode, instead affecting surrounding host tissue in both acute and chronic infections [69]. This suggests that anisakid larva in our case, being degraded, possibly died embedded in patient’s colon, as a plausible outcome for nematode that cannot fulfil reproductive cycle in humans. In such cases, molecular identification by PCR using Anisakis-specific primers is a method of choice that might be also helpful for better resolution of anisakiasis prevalence in old cases. The drawback of DNA isolated from paraffin blocks is the possibility of recovery of a degraded and fragmented DNA that would result in false-negative results [70]. In such cases, design of specific primers that amplify smaller and thus potentially intact DNA loci fragments is suggested to confirm the outcome. Previously only a single case of A. pegreffii infection from an Italian patient was identified from paraffin-embedded tissue [52], while this is the first case of its identification in Croatia.

Consent

Data used in this study were from a patient deceased in 2003 from primary disease other than the one studied in this work. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Croatian National Institute of Public Health (No: 001-41/1-11) based on the given consent of the next of kin.

References

Chai JY, Murrell KD, Lymbery AJ. Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: status and issues. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1233–54.

Pozio E. Integrating animal health surveillance and food safety: the example of Anisakis. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 2013;32:487–96.

Šimat V, Miletić J, Bogdanović T, Poljak V, Mladineo I. Role of biogenic amines in the post-mortem migration of Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae Dujardin, 1845) larvae into fish fillets. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;214:179–86.

Hochberg NS, Hamer DH. Anisakidosis: Perils of the deep. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:806–12.

Umehara A, Kawakami Y, Araki J, Uchida A. Molecular identification of the etiological agent of the human anisakiasis in Japan. Parasitol Int. 2007;56:211–5.

Fumarola L, Monno R, Ierardi E, Rizzo G, Giannelli G, Lalle M, et al. Anisakis pegreffii etiological agent of gastric infections in two Italian women. Foodborne Path Dis. 2009;6:1157–9.

Van Thiel FH, Kuipers FC, Roskam RT. A nematode parasitic to herring, causing acute abdominal syndromes in man. Trop Geogr Med. 1960;2:97–113.

Adams AM, Murrell KD, Cross JH. Parasites of fish and risk to public health. Rev Sci Tech. 1997;16:652–60.

Kim H-J, Park C, Cho S-Y. A case of extragastrointestinal anisakiasis involving a mesocolic lymph node. Korean J Parasitol. 1997;35:63–6.

Yeum C-H, Ma S-K, Kim S-W, Kim N-H, Kim J, Choi K-C. Incidental detection of an Anisakis larva in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis effluent. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1522–3.

Mineta S, Shimanuki K, Sugiura A, Tsuchiya Y, Kaneko M, Sugiyama Y, et al. Chronic anisakiasis of the ascending colon associated with carcinoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:169–74.

HJ Y, Kim SH, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. The association of anisakiasis in the ascending colon with sigmoid colon cancer: CT colonography findings. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:S56–60. doi:10.3348/kjr.2008.9.s.s56.

Hwang D, Park SI, Pack SC, Lee KS, Choib SK, Kang H, et al. A case of duodenal anisakiasis with duodenal ulcer. Chonnam Med J. 2012;48:73–5.

Valle J, Lopera E, Sánchez ME, Lerma R, Ruiz JL. Spontaneous splenic rupture and Anisakis appendicitis presenting as abdominal pain: a case report. J Med Case Report. 2012;6:114. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-114.

Ramanan P, Blumberg AK, Mathison B, Pritt BS. Parametrial anisakidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3430–4. doi:10.1128/JCM.01398-13.

Yorimitsu N, Hiraoka A, Utsunomiya H, Imai Y, Tatsukawa H, Tazuya N, et al. Colonic intussusception caused by anisakiasis: a case report and review of the literature. Internal Med. 2013;52:223–6. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8629.

Choi S-C, Lee S-Y, Song H-O, Ryu J-S, Ahn M-H. Parasitic infections based on 320 clinical samples submitted to Hanyang University, Korea (2004-2011). Korean J Parasitol. 2014;52:215–20. doi:10.3347/kjp.2014.52.2.215.

Dupouy-Camet J, Gay M, Bourgau O, Nouchi A, Léger E, Dei-Cas E. Oesophageal localization: A rare complication of anisakidosis due to Pseudoterranova. Presse Med. 2014;43:91–2. In French.

Gutiérrez-Galindo JF, Osanz-Mur AC, Mora-Ventura MT. Occurrence and infection dynamics of anisakid larvae in Scomber scombrus, Trachurus trachurus, Sardina pilchardus, and Engraulis encrasicolus from Tarragona (NE Spain). Food Control. 2010;21:1550–5. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.03.019.

Strømnes E, Andersen K. Spring rise of whaleworm (Anisakis simplex; Nematoda, Ascaridoidea) third-stage larvae in some fish species from Norwegian waters. Parasitol Res. 2000;86:619–24.

Oshima T. Anisakiasis is the Sushi bar guilty? Parasitol Today. 1987;3:44–8.

Valiñas B, Lorenzo S, Eiras A, Figueiras A, Sanmartín ML, Ubeira FM. Prevalence and risk factors for IgE sensitization to Anisakis simplex in a Spanish population. Allergy. 2001;56:667–71.

Puente P, Anadón AM, Rodero M, Romarís F, Ubeira FM, Cuéllar C. Anisakis simplex: the high prevalence in Madrid (Spain) and its relation with fish consumption. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:271–4.

Rello FJ, Adroher FJ, Benitez R, Valero A. The fishing area as a possible indicator of the infection by anisakids in anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) from southwestern Europe. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;129:277–81.

Levsen A, Lunestad BT. Anisakis simplex third stage larvae in Norwegian spring spawning herring (Clupea harengus L.), with emphasis on larval distribution in the flesh. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:247–53.

Dias FJE, Clemente SCS, Pinto RM, Knoff M. Anisakidae nematodes and Trypanorhyncha cestodes of hygienic importance infecting the king mackerel Scomberomorus cavalla (Osteichthyes: Scombridae) in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:351–5.

Audícana MT, Ansotegui IJ. Fernández de Corres L, Kennedy MW. Anisakis simplex: dangerous — dead and alive? Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:20–5.

Ishikura H, Kikuchi Y, Nagasawa K, Ooiwa T, Takamiya H, Sato N, et al. Anisakidae andanisakidosis, In Sun T, Progress in Clinical Parasitology, Vol III. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1993:43–102.

Matsui T, Iida M, Murakami M, Kimura Y, Fujishima M, Yao Y, et al. Intestinal anisakiasis: clinical and radiologic features. Radiology. 1985;157:299–302.

Daschner A, Alonso-Gómez A, Cabañas R, Suarez-de-Parga JM, López-Serrano MC. Gastroallergic anisakiasis: borderline between food allergy and parasitic disease-clinical and allergologic evaluation of 20 patients with confirmed acute parasitism by Anisakis simplex. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:176–81.

Daschner A, Cuéllar C, Rodero M. The Anisakis allergy debate: does an evolutionary approach help? Trend Parasitol. 2012;28:9–15.

European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion of the Panel on Biological Hazards on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products. EFSA J. 2010;8:10–43. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1543.

Ubeira FM, Anadón AM, Salgado A, Carvajal A, Ortega S, Aguirre C, et al. Synergism between prior Anisakis simplex infections and intake of NSAIDs, on the risk of upper digestive bleeding: a case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1214.

Anadón AM, Rodríguez E, Gárate MT, Cuéllar C, Romarís F, Chivato T, et al. Diagnosing human anisakiasis: recombinant Ani s 1 and Ani s 7 allergens versus the UniCAP 100 fluorescence enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vacc Immunol. 2010;17:496–502.

Daschner A, Alonso-Gómez A, Caballero T, Suarez-De-Parga JM, López-Serrano MC. Usefulness of early serial measurement of specific and total immunoglobulin E in the diagnosis of gastro-allergic anisakiasis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1260–4.

Toro C, Caballero ML, Baquero M, García-Samaniego J, Casado I, Rubio M, et al. High prevalence of seropositivity to a major allergen of Anisakis simplex, Ani s 1, in dyspeptic patients. Clin Diagn Immunol. 2004;11:115–8.

Foti C, Nettis E, Cassano N, Di Mundo I, Vena GA. Acute allergic reactions to Anisakis simplex after ingestion of anchovies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:121–3.

AAITO-IFIACI Anisakis Consortium. Anisakis hypersensitivity in Italy: prevalence and clinical features: a multicenter study. Allergy. 2011;66:1563–9.

Mladineo I, Poljak V, Martínez-Sernández V, Ubeira MF. Anti-Anisakis IgE seroprevalence in the healthy Croatian coastal population and associated risk factors. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2673.

Petrić M, Mladineo I, Krstulović ŠS. Insight into short-finned squid Illex coindetii (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) feeding ecology: is there a link between helminth parasites and food composition? J Parasitol. 2011;97:55–62.

Silva MER, Eiras JC. Occurrence of Anisakis sp. in fish off the Portuguese West coast and evaluation of its zoonotic potential. Bull Eur Ass Fish Pathol. 2003;23:13–7.

Mattiucci S, Abaunza P, Ramadori L, Nascetti G. Genetic identification of Anisakis larvae in European hake from Atlantic and Mediterranean waters for stock recognition. J Fish Biol. 2004;65:495–510.

Gutiérrez-Galingo JF, Osanz-Mur AC, Mora-Ventura MT. Occurrence and infection dynamics of anisakid larvae in Scomber scombrus, Trachurus trachurus, Sardina pilchardus and Engraulis encrasicolus from Tarragona (NE Spain). Food Control. 2010;21:1550–5.

Mladineo I, Šimat V, Miletić J, Beck R, Poljak V. Molecular identification and population dynamic of Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae Dujardin, 1845) isolated from the European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus L.) in the Adriatic Sea. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;157:224–9.

Mladineo I, Poljak V. Ecology and genetic structure of zoonotic Anisakis spp. from Adriatic commercial fish species. AEM. 2014;80:1281–90.

D’amico P, Malandra R, Costanzo F, Castigliero L, Guidi A, Gianfaldoni D, et al. Evolution of the Anisakis risk management in the European and Italian context. Food Res Int. 2014;64:348–62.

Bucci C, Gallotta S, Morra I, Fortnato A, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Anisakis, just think about it in an emergency! Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e1071–2.

Mattiucci S, Fazii P, De Rosa A, Paoletti M, Megna AS, Glielmo A, et al. Anisakiasis and gastroallergic reactions associated with Anisakis pegreffii infection, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:496–9.

Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Criscuolo M, De Benedittis A, Gentile A, Russo S, et al. Human anisakiasis in Italy: a report of eleven new cases. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:429–34.

Montalto M, Miele L, Marcheggiano A, Santoro L, Curigliano V, Vastola M, et al. Anisakis infection: a case of acute abdomen mimicking Chron’s disease and eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:62–4.

Pellegrini M, Occhini R, Tordini G, Vindigni C, Russo S, Marzocca G. Acute abdomen due to small bowel anisakiasis. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:65–7.

Mattiucci S, Paoletti M, Borrini B, Palumbo M, Macarone Palmieri R, Gomes V, et al. First molecular identification of the zoonotic parasite Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in a paraffin-embedded granuloma taken from a case of human intestinal anisakiasis in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:82. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/82.

Valls A, Pascual CY, Martin EM. Anisakis allergy: an update. Rev Fr Allergol. 2005;45:108–13.

Rosales MF, Mascaro C, Fernandez C, Luque F, Sanchez Moreno M, Parras L, et al. Acute intestinal anisakiasis in Spain: a fourth-stage Anisakis simplex larva. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:823–6.

Alonso-Gómez A, Moreno-Ancillo A, López-Serrano MC, Suarez-de-Parga JM, Daschner A, Caballero MT, et al. Anisakis simplex only provokes allergic symptoms when the worm parasitises the gastrointestinal tract. Parasitol Res. 2004;93:378–84.

EFSA. Scientific Opinion on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products1 EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). EFSA J. 2010;8:1543.

López-Penas D, Ramírez Ortiz LM, Del Rosal Palomeque López Rubio F, Fernández-Crehuet Navajas R, Mino Fugarolas G. Study of 13 cases of anisakiasis in the province of Cordoba. Med Clin. 2000;114:177–80.

Daschner A, Alonso-Gómez A, Mora C, Moreno-Ancillo A, Villanueva R, López-Serrano MC. Anisakiasis gastroalérgica con parasitación masiva. Rev Esp Alergol Inmunol Clin. 1997;12:370–3.

Amo Peláez M, Muñoz Codoceo C, Martínez Montiel P, Sánchez Gómez F, Castellano G, Solís Herruzo JA. Anisakiasis múltiple. Rev Esp Enferm Dig (Madrid). 2008;100:581–2.

Cabrera R. Anisakiasis outbreak by Anisakis simplex larvae associated to Peruvian food in Spain. Rev Esp Enferm Dig (Madrid). 2010;102:610–1.

Hubert B, Bacou J, Belveze H. Epidemiology of human anisakiasis: Incidence and source in France. Am Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:301–3.

Bouree P, Paugam A, Petithory J-C. Anisakidosis: Report of 25 cases and review of the literature. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;18:75–84.

Mazzucco W, Lacca G, Cusimano R, Provenzani A, Costad A, Di Notod AM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for IgE sensitization to Anisakis simplex in a Spanish population. Allergy. 2001;56:667–71.

Abattouy N, Valero A, Martín-Sánchez J, Peñalver MC, Lozano J. Sensitization to Anisakis simplex species in the population of northern Morocco. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:514–9.

Lin AH, Nepstad I, Florvaag E, Egaas E, Van Do T. An extended study of seroprevalence of anti-Anisakis simplex IgE antibodies in Norwegian blood donors. Scand J Immunol. 2014;79:61–7. doi:10.1111/sji.12130.

Cuéllar C, Daschner A, Valls A, De Frutos C, Fernández-Fígares V, Anadón AM, et al. Ani s 1 and Ani s 7 recombinant allergens are able to differentiate distinct Anisakis simplex-associated allergic clinical disorders. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:283–8.

Caldarovic O, Franicevic V. Sociological studies on the dietary preferences of fish and other fishery products of the Croatian population. Zagreb: Philosophical Faculty - Department of Sociology; 2007. p. 16–20.

Jurić I, Pogorelić Z, Despot R, Mrklić I. Unusual cause of small intestine obstruction in a child small intestine anisakiasis: report of a case. Scott Med J. 2013;58:e32–6.

Deardorff TL, Jones RE, Kayes SG. Adherence of eosinophils to the epicuticle of infective juveniles of Anisakis simplex (Nematoda: Anisakidae). J Helminthol Soc Wash. 1991;58:131–7.

Deagle BE, Eveson JP, Jarman SN. Quantification of damage in DNA recovered from highly degraded samples – a case study on DNA in faeces. Front Zool. 2006;3:11. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-3-11.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Croatian Scientific Found grant # 5576 to IM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IM and VP had the initial idea for the study and collected and processed the data. MP and IDH isolated DNA from archival histological sections and obtained photodocumentation. Molecular and BLAST analysis was done by IM. Writing was done by IM, while IDH and VP have critically read and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mladineo, I., Popović, M., Drmić-Hofman, I. et al. A case report of Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda, Anisakidae) identified from archival paraffin sections of a Croatian patient. BMC Infect Dis 16, 42 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1401-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1401-x