Abstract

Background

Having rich social networks is associated with better physical and cognitive health, however older adults entering long-term care may experience an increased risk of social isolation and consequent negative impacts on cognitive function. Our study aimed to identify if there is an association between accessing specific types of services or activities within long-term care on social networks and cognition.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 96 residents from 2 aged care providers in New South Wales, Australia. Residents were given a battery of assessments measuring social network structure (Lubben Social Network Scale, LSNS-12), quality of life (EuroQol 5D, Eq. 5D5L) and cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA). Demographic factors and service use factors were also collected from aged care providers’ electronic records. Independent sample t-test, ANOVA and linear regression analyses were used to explore associated factors for cognition.

Results

Residents had a mean age of 82.7 ± 9.4 years (median = 81) and 64.6% were women. Most residents had cognitive impairment (70.8%) and reported moderate sized social networks (26.7/60) (Lubben Social Network Scale, LSNS-12). Residents who had larger social networks of both family and friends had significantly better cognitive performance. Service type and frequency of attendance were not associated with cognitive function.

Conclusions

Among individuals most at risk of social isolation, having supportive and fulfilling social networks was associated with preserved cognitive function. The relationship between service provision and social interactions that offer psychosocial support within long-term facilities and its impact over time on cognitive function requires further exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As we approach older adulthood, opportunities for social interaction, availability of social support and active participation in socially stimulating activities often decrease. However, the value assigned to psychosocial components of ageing such as contribution to community and embodiment of social roles are identified as hallmarks of successful ageing amongst older adults [1]. Thus, maintaining social engagement is not only important throughout the life course it is particularly valuable as we get older. Remaining socially connected has beneficial effects on our physical and mental health, life satisfaction, quality of life, inclination to adopt positive health behaviours and reduced risk of functional decline and mortality [2]. The protective effects of sustaining social engagement on physiological processes associated with the delay of cognitive decline and dementia suggest it may support inflammatory processes, cardiovascular health and cognitive reserve, which refers to the underlying processes that equip the brain with flexibility and capacity to function adequately despite brain changes or damage [3,4,5,6,7].

A larger evidence base for structural (i.e., network size, frequency of contact and social activity participation) [6, 8] compared to functional aspects (i.e., social support and satisfaction with network) [9,10,11] of social relationships have been associated with a reduced risk of developing dementia. In an ageing society, without a cure yet, and with prevalence rates remaining high and rising rapidly in certain regions, the impact of dementia will continue to place large financial pressure on global health care systems through recurrent and prolonged demand for both health and aged care services [12,13,14]. Thus, deconstructing key elements of social stimulation and determining associations with cognition are worth exploration.

Recent cross-sectional and longitudinal studies provide further insight into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between social connection and cognition in older adults. Cross-sectional studies highlight that having larger social networks [15], more frequent interaction with friends rather than family [16], and receiving adequate social support [17] are associated with better cognitive function. Additional studies have found that better cognition is linked with older adults’ ability to maintain and create connections between their network members [18].

Longitudinal studies reinforce similar results. Greater emotional support [11], and larger networks consisting specifically of friendships [19, 20] are associated with sustained levels of overall cognition [21]; and that social disengagement [22, 23] and infrequent social activity participation is associated with an increased chance of developing dementia [24]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that social contact helps to build and sustain cognitive reserve which can act as a protective factor for future cognitive decline [25].

However, synthesised findings from systematic reviews and meta-analyses collectively demonstrate inconsistent evidence for satisfaction with social networks and that poor social engagement, defined by living alone, inadequate social support, minimal social contacts and lack of social activity is associated with increased dementia risk in later life [8,9,10].

The above-mentioned studies are primarily based on older adults living in the community or retirement villages and cannot be generalised to older adults requiring long-term care in permanent residential care homes, defined as care required in multiple facets of living for a prolonged period [26]. The social environment within institutionalised settings is often distinct from the general population and distinguished by substantial decrease in the quantity and quality of their social connections [27,28,29]. Typically, residents have significantly fewer social ties, a low number of new connections being made and of these, a lack of mutual friendships or reciprocity [29,30,31]. Residents also rely on pre-existing relationships with family and friends outside of the facility, are often unable to form meaningful social connections with others within the facility due to physical limitations, cognitive and communication difficulties, and have less opportune moments for social activity due to restrictive routines [31].

In a systematic review of factors associated older adults’ social networks, nine studies in institutional care were identified [30]. Of these, having more connections with others indicated higher quality of life and cognitive status [32] and similarly, residents with higher cognitive deficits also reported less social ties [28]. However, several limitations prompt the need for further evaluation of the social factors for cognition in long-term care. These include inconsistently administered social network tools [28, 29, 32, 33], small sample sizes (ranging from 10 to 36 participants), and data obtained from only one aged care provider [28, 29, 32, 34], which all limit generalisability and interpretation.

Long-term care psychosocial services and activities (e.g., exercise class, reminiscence group) are primary sources of social interaction for residents in aged care facilities. However, the investigation of service use factors including type and frequency of activities and their impact on cognitive function inside facilities remains unknown [7]. Current knowledge is derived from activity participation amongst community dwelling older adults (e.g., facilitator led discussions, field trips, outings, religious activities, amongst others) which has propitious outcomes for better brain health and cognitive functioning [7, 35,36,37]. For example, by participating in a larger variety of services or activities [7, 37], older adults in the community have the potential to expand their social interactions and gain educational and creative opportunities, which may assist in maintaining quality of life [38, 39], improve functional health outcomes (activities of daily living) [40] and preserve cognitive performance [37]. Yet, this direct association remains unexplored. More extensive analysis of activity participation and their association with cognitive function in long-term care may further assist with optimising resident outcomes. During the pandemic, lockdowns posed a significant challenge for maintaining social contact for older adults due to their vulnerability to the disease and increased physical isolation [41]. Evidence suggests that being able to maintain a feeling of connection with a community may have had protective effects on perceived social isolation during the restrictive period of COVID-19 amongst community-dwelling adults, despite marked reductions in quality of life, wellbeing and life satisfaction [42, 43].

Our study thus aimed to identify the association between accessing specific types of services within long-term care, social networks and cognition pre-pandemic. This research will further assist in understanding the extent of the detrimental impact of the pandemic on social networks and cognition in aged care facilities faced with staffing restrictions, changes to usual visiting practices and a halt in psychosocial and recreational activities.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study design in seven facilities across two aged care providers comprising both metropolitan and regional-based facilities in the Central Coast and Greater Sydney regions of New South Wales, Australia was conducted. In total, the facilities housed 635 residents. A complete sampling approach was used, where residents who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e. aged 55 years or older, no diagnosis of advanced dementia, no history of significant brain trauma, stroke or epilepsy, no vision or severe hearing impairment) were invited to participate by their facility manager. Residents who expressed interest were then approached by members of the research team. Data was collected between September 2019 and January 2020.

Ethical considerations

The Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval for this study prior to commencement of participant recruitment (reference number: 5159).

Data collection and procedure

Participants were assessed on competency to provide consent per the study’s ethics protocol prior to obtaining written consent and engagement in the interview. Interviews ranged from 20 to 40 min in duration. Each participant provided information about their demographics (age, gender, marital status, educational level) and completed validated measures on social networks, cognition, and quality of life. Participants were then provided with a gift voucher to acknowledge their time and input into the research project. Following the completion of interviews, service use and resident information in the month prior to the date of interview assessment was extracted from the providers’ electronic database management system.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information was collected from the individual including age, gender, relationship and pension status, country of birth and main language spoken, highest level of education attained, religious affiliation, previous occupation, medical conditions/history (including number of falls in past 6 months) and current medications. Participant age, marital and pension status, medical conditions/history (including falls and mobility status), and current medications were verified with electronic service provider data.

Social networks

Social networks were assessed using the Lubben Social Network Scale-12 (LSNS-12) [44] which measures structural (e.g., network size, composition), interactional (e.g., duration of respondents’ relationships, frequency of contact, quality of exchange) and functional components (e.g., purpose of support) of the respondent’s contacts. The total score is calculated by summing all the items, with a higher score indicating more social engagement and better networks. For the LSNS-12, the score ranges between 0 and 60. LSNS-12 has strong methodological qualities (internal reliability 0.83) and has been developed specifically for older adults [44, 45].

Cognition

Classification of cognitive status was conducted by in-person administration of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [46], a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. The MoCA has an estimated duration of ten minutes, and assesses visuospatial/executive function, naming, episodic memory, attention, language, abstraction, and orientation. The total possible score is 30 points. The original manual cites a score of 26 or above as normal, however a cut-off score of 23 has recently been recommended for greater diagnostic accuracy [47]. The MoCA has acceptable psychometric properties [48], and at an optimal cut-off of below 22 for MCI, the MoCA is considered to counteract the limitations of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), achieving significantly superior values in sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and classification accuracy in High Income Settings [49]. The MoCA has been validated for a variety of different languages and aetiologies [50,51,52,53], including Alzheimer’s disease.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-5L scale, which is a generic instrument consisting of a self-administered health index and a visual analogue scale (VAS), a 20-cm scale in which respondents are asked to rate their current health state [54]. It is a brief instrument, representing five dimensions of health related quality of life [55], as opposed to quality of life in general [56, 57]. The EQ-5D-5L contains five domains: mobility, self-care, pain/discomfort, usual activities and anxiety/depression. There are five levels per dimension: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems or extreme problems. For the items measuring experience of pain and anxiety, the five ratings relate to the severity of symptoms. Utility scores quantify health-related quality of life along a continuum that ranges from − 0.59 (worst health) to 1.00 (perfect health). Respondents are asked to mark their current health state on a 100-point VAS scale, with 100 representing the ‘best imaginable health state’ and 0 representing the ‘worst imaginable health state’.

EQ-5D-5L data was converted into health utility scores, providing a single evaluation, using the time trade-off method based on the tariff developed for the EQ-5D-5L index in the UK [58]. This scale has high measurement properties, improved discriminatory power and establishing convergent and known groups validity [58].

Service use

Frequency of service use was extracted from the providers’ electronic database management system one month prior to the date of interview for each resident. Frequency refers to the number of times a participant attended a particular service type in the last 30 days. A one-month time-frame was selected for numerous reasons. It ensured that the data captured reflected the current state of service use amongst residents and allowed for precision and targeted analysis when evaluating the impact of psychosocial activities which is particularly important when activities vary each month. It also enhanced efficiency in data storage, processing and analysis as well as minimised staff burden without compromising the value of the data. To streamline service types between providers, the research team re-categorised existing data into four distinct categories: (1) cognitive (e.g. quizzes, puzzles, crosswords, news and current affairs, cognitive and sensory stimulation, music and memory, dementia specific programs, reminiscence therapy), (2) physical (e.g. walks, exercises, fine and gross motor skill activities, chair aerobics, tai chi), (3) social (e.g. conversation groups, one on one time, special events, visitors, happy hour, breakfast club, coffee club, school student visit, high tea, men’s club, knitting club) and (4) personal interests (e.g. horticulture, spiritual, reading, art and craft, pet therapy, musical, cooking group, outings, hairdresser visits, shopping). Total number of service attendances was also computed.

Other resident information

Additionally, resident date of admission into facility and medical conditions and mobility status were also extracted from provider’s electronic database management system.

Control variables

Potential confounding variables of demographic and socioeconomic determinants on cognitive function were controlled for in the analyses and included age, gender, education and marital status as identified from the literature [59]. There were no missing data.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses for all continuous variables, including variables that were not normally distributed, were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine associations between: (i) social networks and quality of life; (ii) social networks and residential care service utilisation; and (iii) social networks and cognition. Analyses were performed to build a step-wise model adjusted for demographics (age, gender, marital status and education) identified in the literature as potential covariates. Adjusted R2 values were reported for regression models to indicate the proportion of variance explained by variables in the model. Regression coefficients were also reported. All analyses were conducted using SPSS V25.

Results

Descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants (n = 96) had a mean age of 82.7 years (median = 81), were mostly women (64.6%), widowed (58.3%), born in an English-speaking country (88.5%), and been a resident of the facility for an average of 2.3 years.

Residents reported greater ties with their family circle (18.4 out of 30) more so than friends (9.3 out of 30) which contributed to a mean social network score of 26.7 (out of a possible 60), indicating residents were socially integrated. A total social network score of less than 20 indicates an extremely limited social network, with 29.2% participants meeting this criterion. There was substantial variation (range 0–52, interquartile range [IQR] 35,75).

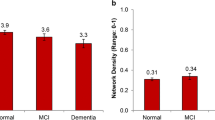

Quality of life was moderately low with mean utility and EQ-VAS scores of 0.6 (SD = 0.3) and 70.2 (SD = 19.7), respectively. Problems with mobility were the most frequently reported, two-thirds (68.8%) with slight to extreme mobility issues (level 2 or more), and around one in seven (14.6%) reporting that they are unable to walk (level 4 or 5) (Table 2). In contrast nearly three-quarters of residents (74.0%) reported no issues carrying out daily activities. Majority of residents were cognitively impaired with 70.8% of individuals scoring less than 22 and an average MoCA score of 16.8 (SD = 6.3) out of a possible 30. There were no significant associations between quality of life (EQ-VAS score and utility index) and cognition (p > 0.05).

Residents attended an average number of 52.6 (SD = 44.0) activities across a one-month period with 63% of residents attending all four types of activities (Table 1). Of these, residents tended to attend social activities the most (mean = 17.2 sessions, SD = 12.8) and cognitive activities the least (mean = 8.8 sessions, SD = 10.9). There was no clear relationship between frequency of long-term care activity attendances or taking part in multiple activity types and cognition.

In the univariate analysis, younger age (p = 0.039), more years of education (p = 0.002), high social networks (p = 0.04), high family network score (p = 0.04) and being born in an English-speaking country (p = 0.003) were significant predictors of higher cognitive function (Table 3). Linear stepwise regression of cognitive function (model adjusted R2 = 0.17, F[13,76] = 2.42, p = 0.002) using social network, service use, quality of life and demographic parameters resulted in only one significant predictor: residents with high social networks (ß=0.15, p 0.01) had higher cognition. Service use type or frequency did not predict cognition in this model (Table 4).

Discussion

We investigated cross-sectional relationships between the characteristics of social networks, cognition, quality of life and service activity frequency and type in the preceding month amongst older adults in two long-term care settings. Individuals with larger social networks including family and friend connections had better cognition. The relationship between social networks and cognitive function were independent of quality of life and specific activity type and attendance. These findings provide useful insights into the factors associated with better cognition in older long-term care adults and contributes to the view that aged care reform may be necessary to optimise activities and opportunities that support residents’ cognition and social wellbeing.

Frequency of attendance and type of scheduled activities within the facility was not related to cognitive performance. Given the promising evidence on the link between service attendance and better outcomes on older adults’ social engagement, brain health, functional status and wellbeing [35, 37] this finding is surprising, but also hopeful post pandemic in that the detrimental impacts of reductions in recreational activities for residents in long-term care may have influenced some aspects of physical and mental health but not others [60]. Although activity attendance is the most consistently reported indicator of social participation across community day centres and long-term care facilities [61], our study highlights that the relationship between activities, social networks and cognition is more complex. It may be that residents with declining cognition and function are less likely to participate in social activities [62], or that existing larger social networks and guaranteed social engagement have a protective effect on cognitive function [5, 6]. However, evidence over time is inconclusive and specific to cognitive domains [7, 35, 37, 63]. The social connections developed in long-term care can overcome social isolation, create a sense of autonomy and counterbalance resident’s physical limitations in some circumstances [64]. Therefore, it is essential to determine whether scheduled activities act as facilitating agents or preclude the broadening of social networks and improvements in cognition as favourable mechanisms remain unknown. Future studies adopting a longitudinal design with longer follow-up periods and a larger sample size may contribute further knowledge.

In other studies, residents have reported that most social interaction within the facility occurs in public spaces e.g., corridor, café or during visits/outings with family members rather than scheduled activities [31, 65, 66]. Planned activities were seen as spaces where residents were physically together but were insufficient at promoting positive participation and conversation e.g. assigned seating at mealtimes [31, 67], thus residents remained unfamiliar with each other [31, 65]. This implies that broadening social networks through traditional service provision may be unattainable. Instead, it calls for research into the structure, quality and nature of engagement in recreational programming in long-term care to provide residents with psychosocial support from meaningful, ecological and fulfilling social encounters.

Having larger overall social networks was the main driving factor for greater cognition. This is consistent with previous cross-sectional [15, 32, 37] and longitudinal data [22,23,24] for older adults in the general population and those accessing community aged care services. Our results suggest that having access to a greater number of close social ties, and repeated social engagement unique to this setting (i.e., with staff, family members, long-term friends, other residents) may reflect positively on cognitive health. Previous evidence suggests a residents’ typical social network in long-term care is static (no incoming or outgoing social ties), with friendship ties that lack mutuality [30]. Additionally, long-term care characteristics such as facility size, limited choice in social partners, reduced resources for social engagement, unique resident mix (which predominantly consists of individuals who are cognitively impaired) and various other uncertainties (length of time until death, major health deteriorations and discharges) are recognised barriers to forming new friendships [28, 31, 68, 69]. Considering this, and the higher number of family contacts reported in our study, residents may invest a greater degree of effort and emotional affection into maintaining established long-term relationships with family members [31].

Previous research suggests that years of education and actively working to preserve cognition across the life-span provides protective effects from cognitive decline (e.g., helping to build cognitive reserve and delaying the clinical expression of dementia) [36, 70, 71]. Distinct from these studies, this study suggests education was not significantly associated with cognitive impairment. A reason for this may be that in comparison to adults in the general population or accessing community care, individuals in residential aged care are older, with 58% of people in long-term care over the age of 85 compared to 41% of those accessing home care [72]. This is reflected in the average age of our study population which is relatively high (82.7). The protective effects of education attainment may only work below a threshold at which normative age-related impairments may surpass [73]. Therefore, the extent to which years of education can stave off cognitive decline is potentially limited in the later years of life.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, using a cross-sectional design, causality is not assumed as reverse causality is a possibility, with poorer functional and cognitive status being associated with ageing, which can influence the ability to navigate social relationships [18, 62] and lead to social withdrawal [74]. Furthermore, older age, cognitive impairment and social vulnerability are also known predictors of entry into long-term care [75]. It was beyond the scope of this study to identify whether participants had experienced diminishing social networks or some level of cognitive impairment prior to admission into long-term care, however future studies should adopt a longitudinal approach to investigate the relationship between psychosocial service use, cognition, and social networks over longer periods of time.

Secondly, we were only able to recruit from two aged care providers, and the study outcomes and nature of the population required researchers to select participants through the provider. Willingness to participate and eligibility was assessed by the staff, which may be a potential source of bias. The lack of missing data is unusual suggesting some bias in selection of those able and sufficiently well to participate and willing to respond to all questions. Despite this, researchers did not encounter any drop outs when approaching residents to participate, enhancing the generalisability of the findings [76]. Studies should further explore objective measures of quality of life and cognition as reported measures remain high for this population group (i.e., over three quarters reporting no assistance required for activities of daily living), however residents were pre-selected by staff and thus might be biased. Another option would be verifying self-reported responses with staff or family reported observations to ensure researchers are not solely relying on residents’ perceived needs. Another source of bias could stem from the decision to extract one month of psychosocial service use data, whereas a longer period of time would more sufficiently depict typical resident activity attendance. Finally, this study is limited in its assessment of psychosocial service use through activity attendance and excludes those who may have specific social participation goals (i.e. prefer not to participate), and neglects the shared experiences that naturally occur outside of these activities in long-term care [31].

Implications

The nature and design of activity programs in long-term care could also be a critical factor contributing to cognitive health. Many activities in long-term care are not tailored to the functional or social needs of the residents and are incongruent with their interests and expectations of friendship [29, 61]. For example, residents with cognitive impairment often refrain from attending activities or adopt a passive and superficial approach to interactions due to communication difficulties; residents with functional limitations i.e., visual or hearing impairments may require assistive technologies to participate which are not always accessible [77]; and those requiring more physical care may also have restrictive routines which limit their activity choices [61]. It is possible that inclusion of resident preferences for recreational programming was inadequate, or that activities were unable to provide relief from the monotony of their daily routine [31, 78].

Indeed, recreational activities in long-term care are often void of opportunities for choice and autonomy, learning or personal development and instead are provided with the intention to entertain or distract [31, 61, 79]. Future studies should seek to observe the social components of recreational programs that contribute a sense of coherence, value and purpose for residents. This includes standardising activity participation reporting and measurement to include frequency, duration, level of social engagement as well as satisfaction and perceived social support within long-term care to gather a more holistic view of residents’ social context that accounts for the interaction of life experience, life stage and the environment [80]. Emerging research from population-based studies suggests that the role of risk factors for cognitive decline, including social integration and engagement amongst others, differ according to context (e.g., built environment, residential location) and life stage which may have ramifications for levels of cognitive preservation [25, 81]. Thus, a more extensive evaluation of the social context in long-term care will help to determine whether residents’ social needs are being met as well as explore the mechanisms within these psychosocial and recreational services that are associated with resident cognition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our current study advances the understanding of the relationship between social networks and cognitive function in the context of long-term care. We suggest that a larger social network may be associated with cognitive health benefits for older adults accessing long-term care services. However, despite this potential, the persistent challenge of fostering social inclusion through conventional psychosocial service delivery remains evident for policymakers and long-term care service providers. Thus, there is an evolving realisation that traditional or customary approaches may not yield the presumed efficacy in promoting both social and cognitive wellbeing. Consequently, there is a need for further investigation into the quality of social interactions and the interpersonal dynamics within the social context that underlie the design and implementation of service provision. Such research endeavours will deepen our comprehension of how social inclusion strategies impact cognitive health, providing valuable insights for the improvement of long-term care practices.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LSNS-12:

-

Lubben Social Network Scale

- EQ5D5L:

-

EuroQol 5D

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

References

Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BCM, Brayne C. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002710. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002710.

Bath PA, Deeg D. Social engagement and health outcomes among older people: introduction to a special section. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2(1):24–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-005-0019-4.

Cherry KE, Walker EJ, Brown JS, Volaufova J, Lamotte LR, Welsh DA, et al. Social Engagement and Health in younger, older, and oldest-old adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32(1):51–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464811409034.

Sachdev PS. Social health, social reserve and dementia. Curr Opin. 2022;35(2):111–7.

Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(6):343–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7.

Wang H, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the kungsholmen project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(12):1081–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/155.12.1081.

Wang H-X, Xu W, Pei J-J. Leisure activities, cognition and dementia. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2012;1822(3):482–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.002.

Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC, Zuidema SU, van Den Heuvel ER, Stolk RP, et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22(C):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006.

Penninkilampi R, Casey AN, Singh MF, Brodaty H. The Association between Social Engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1619–33. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-180439.

Evans IEM, Martyr A, Collins R, Brayne C, Clare L. Social isolation and cognitive function in later life: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(s1):119–s44. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-180501.

Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):243. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243.

Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, Prina M, et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia, an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI); 2015. 7 July 2023.

World Health Organization. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: a public health priority. UK: World Health Organisation; 2012.

Access Economics. Keeping dementia front of mind: incidence and prevalence 2009–2050. Alzheimers Australia; 2009.7 July 2023.

Schafer MH. Structural Advantages of Good Health in Old Age: investigating the health-begets-position hypothesis with a full Social Network. Res Aging. 2012;35(3):348–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027512441612.

Fu C, Li Z, Mao Z. Association between Social activities and cognitive function among the Elderly in China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020231.

Li J, Wang Z, Lian Z, Zhu Z, Liu Y, Social Networks. Community Engagement, and cognitive impairment among Community-Dwelling Chinese older adults. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;9(3):330. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502090.

Cornwell B. Good Health and the bridging of Structural Holes. Social Networks. 2009;31:92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2008.10.005.

Giles LC, Anstey KJ, Walker RB, Luszcz MA. Social Networks and memory over 15 years of Followup in a cohort of older australians: results from the Australian longitudinal study of Ageing. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:856048. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/856048.

Sharifian N, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Zahodne LB. Social network characteristics and cognitive functioning in ethnically diverse older adults: the role of network size and composition. Neuropsychology. 2019;33(7):956–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000564.

Sommerlad A, Sabia S, Singh-Manoux A, Lewis G, Livingston G. Association of social contact with dementia and cognition: 28-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(8):e1002862. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002862.

Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(3):165–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002.

Zhou Z, Wang P, Fang Y. Social Engagement and its change are Associated with Dementia Risk among Chinese older adults: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1551. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17879-w.

Zunzunegui M-V, Alvarado BE, Del Ser T, Otero A, Social Networks. Social Integration, and Social Engagement Determine Cognitive decline in Community-Dwelling Spanish older adults. J Gerontol - B Psychol Sci. 2003;58(2):93–S100. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.2.S93.

Evans IEM, Llewellyn DJ, Matthews FE, Woods RT, Brayne C, Clare L, et al. Social isolation, cognitive reserve, and cognition in healthy older people. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201008.

Roberts K. International aged care: a quick guide. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2017.

Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP Study. J Gerontol - B Psychol Sci. 2009;64B(suppl1):i38–i46. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp037.

Abbott KM, Pachucki MC. Associations between social network characteristics, cognitive function, and quality of life among residents in a dementia special care unit: a pilot study. Dement (London). 2017;16(8):1004–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301216630907.

Casey A-NS, Low L-F, Jeon Y-H, Brodaty H. Residents perceptions of friendship and positive Social Networks within a nursing home. Gerontologist. 2015;56(5):855–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv146.

Ayalon L, Levkovich I, A Systematic Review of Research on Social Networks of Older Adults. Gerontologist. 2018;59(3):e164–e76. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx218.

Park NS, Zimmerman S, Kinslow K, Shin HJ, Roff LL. Social Engagement in assisted living and implications for practice. J Appl Gerontol. 2012;31(2):215–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464810384480.

Hardiman K. Social networks, depression, and quality of life among women religious in a residential facility. In: Cannon B, editor.: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2017.

Abbott KM, Bettger JP, Hampton KN, Kohler HP. The feasibility of measuring social networks among older adults in assisted living and dementia special care units. Dement (London). 2015;14(2):199–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213494524.

Abbott KM, Bettger JP, Hampton K, Kohler H-P. Exploring the Use of Social Network Analysis to measure Social Integration among older adults in assisted living. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(4).

Kelly ME, Duff H, Kelly S, McHugh Power JE, Brennan S, Lawlor BA, et al. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6.

Siette J, Georgiou A, Brayne C, Westbrook JI. Social networks and cognitive function in older adults receiving home- and community-based aged care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104083.

Herzog AR, Franks MM, Markus HR, Holmberg D. Activities and well-being in older age: effects of Self-Concept and Educational Attainment. Psychol Aging. 1998;13(2):179–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.13.2.179.

Lampinen P, Heikkinen RL, Kauppinen M, Heikkinen E. Activity as a predictor of mental well-being among older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(5):454–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600640962.

de Leon CFM, Seeman TE, Baker DI, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Self-efficacy, physical decline, and change in Functioning in Community-Living elders: a prospective study. J Gerontol - B Psychol Sci. 1996;51B(4):183–S90. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/51B.4.S183.

Dawes P, Siette J, Earl J, Johnco C, Wuthrich V. Challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic for social gerontology in Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2020;39(4):383. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12845.

Siette J, Dodds L, Seaman K, Wuthrich V, Johnco C, Earl J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of older adults receiving community‐based aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2021;40(1):84–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12924.

Clair R, Gordon M, Kroon M, Reilly C. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit soc sci. 2021;8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3.

Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health. 1988.

Siette J, Pomare C, Dodds L, Jorgensen M, Harrigan N, Georgiou A. A comprehensive overview of social network measures for older adults: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;97:104525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2021.104525.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief Screening Tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x.

Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ. A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):379–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4756.

Sweet L, Van Adel M, Metcalf V, Wright L, Harley A, Leiva R, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in geriatric rehabilitation: psychometric properties and association with rehabilitation outcomes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(10):1582–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610211001451.

Freitas S, Simoes MR, Alves L, Santana I. Montreal cognitive assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(1):37–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bfe.

Tsai CF, Lee WJ, Wang SJ, Shia BC, Nasreddine Z, Fuh JL. Psychometrics of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and its subscales: validation of the Taiwanese version of the MoCA and an item response theory analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(4):651. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610211002298.

Beath N, Asmal L, van den Heuvel L, Seedat S. Validation of the Montreal cognitive assessment against the RBANS in a healthy South African cohort. SAJP. 2018;24:1304. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v24i0.1304.

Freitas S, Prieto G, Simoes MR, Santana I. Psychometric properties of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): an analysis using the Rasch model. Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;28(1):65–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2013.870231.

Benabdeljlil M, Azdad A, Mustapha EAF. Standardization and validation of montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) in the Moroccan population. J Neurol Sci. 2017;381:318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.901.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6.

EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9.

Lawton MP. Assessing quality of life in Alzheimer disease research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 6):91–9.

Siette J, Knaggs GT, Zurynski Y, Ratcliffe J, Dodds L, Westbrook J. Systematic review of 29 self-report instruments for assessing quality of life in older adults receiving aged care services. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e050892. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050892.

Dolan P. Modelling valuations for health states: the effect of duration. Health Policy. 1996;38(3):189–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(96)00853-6.

Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of Dementia. Rev JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.4782.

Thomas S, Bolsewicz K, Latta R, Hewitt J, Byles J, Durrheim D. The Impact of Public Health Restrictions in residential aged care on residents, families, and Staff during COVID-19: getting the Balance Right. J Aging Soc Policy. 2022:1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2022.2110802.

Theurer K, Mortenson WB, Stone R, Suto M, Timonen V, Rozanova J. The need for a social revolution in residential care. J Aging Stud. 2015;35:201–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2015.08.011.

Green AF, Rebok G, Lyketsos CG. Influence of social network characteristics on cognition and functional status with aging. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):972–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2023.

Aartsen MJ, Smits CH, van Tilburg T, Knipscheer KC, Deeg DJ. Activity in older adults: cause or consequence of cognitive functioning? A longitudinal study on everyday activities and cognitive performance in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(2):P153–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.2.p153.

Gleibs IH, Sonnenberg SJ, Haslam C, Activities. Adaptation Aging. 2014;38(4):259–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2014.966542.

Li C, Kang K, Lin X, Hu J, Hengeveld B, Hummels C. Promoting older residents’ Social Interaction and Wellbeing: A Design Perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(7):2834.

Siette J, Dodds L, Surian D, Prgomet M, Dunn A, Westbrook J. Social interactions and quality of life of residents in aged care facilities: a multi-methods study. PloS One. 2022;17(8):e0273412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273412.

Martin MD, Hancock GA, Richardson B, Simmons P, Katona C, Mullan E, et al. An evaluation of needs in elderly continuing-care settings. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):379–88. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610202008578.

Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Connell BR, Hollingsworth C, King SV, et al. Managing decline in assisted living: the key to aging in place. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(4):202–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.4.s202.

Sikorska E. Organizational determinants of resident satisfaction with assisted living. Gerontologist. 1999;39(4):450–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.4.450.

Meng X, D’Arcy C. Education and Dementia in the context of the Cognitive Reserve Hypothesis: a systematic review with Meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038268.

Brayne C, Ince PG, Keage HA, McKeith IG, Matthews FE, Polvikoski T, et al. Education, the brain and dementia: neuroprotection or compensation? Brain. 2010;133(Pt 8):2210–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq185.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. People using aged care: AIHW; 2021 [updated 27 Apr 2021. Available from: https://www.gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/Topics/People-using-aged-care.

Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and cognitive functioning across the Life Span. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020;21(1):6–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620920576.

Ayalon L, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Roziner I. A cross-lagged model of the reciprocal associations of loneliness and memory functioning. Psychol Aging. 2016;31(3):255–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000075.

Kendig H, Browning C, Pedlow R, Wells Y, Thomas S. Health, social and lifestyle factors in entry to residential aged care: an Australian longitudinal analysis. Age Ageing. 2010;39:342–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq016.

Banack HR, Kaufman JS, Wactawski-Wende J, Troen BR, Stovitz SD. Investigating and remediating selection Bias in Geriatrics Research: the selection Bias Toolkit. JAGS. 2019;67(9):1970–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16022.

Jaiswal A, Fraser S, Wittich W. Barriers and facilitators that influence social participation in older adults with dual sensory impairment. Front Educ. 2020;5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00127.

Annear MJ, Elliott K-EJ, Tierney LT, Lea EJ, Robinson A. Bringing the outside world in: enriching social connection through health student placements in a teaching aged care facility. Health Expectations: Int J Public Participation Health care Health Policy. 2017;20(5):1154–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12561.

Hay ME, Mason ME, Connelly DM, Maly MR, Laliberte Rudman D. Pathways of participation by older adults living in Continuing Care homes: a Constructivist grounded Theory Study. Act Adapt Aging. 2020;44(1):1–23.

Koelen M, Eriksson M, Older, People. Sense of coherence and community. Springer International Publishing; 2022. pp. 185–99.

Brayne C, Wu Y-T. Population-Based studies in Dementia and Ageing Research: a local and national experience in Cambridgeshire and the UK. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2022;37:15333175221104347. https://doi.org/10.1177/15333175221104347.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the aged care providers and residents who supported and participated in this research and dedicated much of their time.

Funding

This work was supported by a Macquarie University Restart Grant awarded to JS. The funding body did not influence the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joyce Siette: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision. Laura Dodds: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration. Carol Brayne: Validation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval for this study (reference number: 5159). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dodds, L., Brayne, C. & Siette, J. Associations between social networks, cognitive function, and quality of life among older adults in long-term care. BMC Geriatr 24, 221 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04794-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04794-9