Abstract

Background

Frailty and cognitive impairment are two common geriatric symptoms linking adverse health-related outcomes. However, cognitive frailty, a new definition defined by an international consensus group, has been shown to be a better predictor of increased disability, mortality, and other adverse health outcomes among older people than just frailty or cognitive impairment. This study estimated the prospective association between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty over 1 year follow-up, and whether psychological distress mediated the association.

Methods

The data was drawn from a prospective repeated-measures cohort study on a sample of participants aged 60 and over. A total of 2785 older people who participated in both of the baseline and 1-year follow-up survey were included for the analysis. Cognitive frailty was measured by the coexistence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment without dementia. Control variables included sex, age, education, marital status, economic status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, chronic conditions, and functional disability. Path analyses with logistic function were performed to examine the direct effects of social support (predictors) on subsequent cognitive frailty (outcome) at 1-year follow-up and the mediating role of psychological distress (mediator) in this link.

Results

After adjusting for covariates and prior cognitive frailty status, social support was negatively associated with psychological distress (β = − 0.098, 95% CI = − 0.137 to − 0.066, P < 0.001) and was negatively associated with the log-odds of cognitive frailty (β = − 0.040, 95% CI = − 0.064 to − 0.016, P < 0.001). The magnitude of mediation effects from social support to cognitive frailty via psychological distress was a*b = − 0.009, and the ratio of a*b/(a*b + c’) was 24.32%.

Conclusions

Lower social support is associated with increased rates of subsequent cognitive frailty over 1-year follow-up, and this link is partially mediated through psychological distress, suggesting that assessing and intervening psychological distress and social support may have important implications for preventing cognitive frailty among older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frailty and cognitive impairment are two common geriatric symptoms linking adverse health-related outcomes [1]. However, cognitive frailty, a new definition proposed by the International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (I.A.N.A) and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (I.A.G.G) in 2013, was defined as “a heterogeneous clinical condition characterized by the simultaneous presence of both physical frailty and cognitive impairment and the exclusion of concurrent Alzheimer disease or other dementias” [2]. Increasing studies have shown that cognitive frailty plays a better role in predicting the short-term and the long-term all-cause mortality, disability, dementia, and other adverse health outcomes among older people than just frailty or cognitive impairment [3,4,5,6]. Importantly, the condition of cognitive frailty could recovery physically robust and/or cognitively normal due to its reversible process if effective interventions were employed [7]. Therefore, it is imperative to identify predictive and modifiable risk factors and underlying mechanisms concerning cognitive frailty in order to inform intervention strategies among older people. However, to date, the possible determinants as well as the underlying mechanisms of cognitive frailty among older people are still poorly understood.

One potential modifiable protective factor for cognitive frailty among older people is social support [8], which is defined as “the perceived and actual assistance that individuals can receive from family, friends, and other connections in the social environment” [9]. Many studies have shown that social support is associated with increased risk of both physical frailty and cognitive impairment among older people [10, 11]. However, previous studies on the association between social support and cognitive frailty are predominantly cross-sectional [12, 13], we found no prospective study specifically examined the longitudinal association between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty among older people in rural China. Identifying mediating factors could be important to further understand the relationship between social support and cognitive frailty. The psychological process driving the link between social support and cognitive frailty is not clear. Previous studies in other countries have shown that psychological health is associated with both of cognitive frailty [6] and social support [14], suggesting that the association between social support and cognitive frailty might be through psychological mechanism. While prior studies have investigated the direct effects of both social support and psychological health on cognitive frailty separately, no study has investigated potential mediating effects of psychological health on the link between social support and cognitive frailty among older people. In addition, previous studies have shown that psychological health plays an important mediating role in relationships between some factors and health [15, 16]. A recent study has shown that the relationship between cognitive function and physical frailty is partially mediated by psychological distress [17]. Consequently, one of the underlying mechanisms between social support and cognitive function might be through psychological distress.

Using the longitudinal data from the Shandong Rural Elderly Health Cohort (SREHC), the current analysis was conducted to understand the link between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty over 1-year follow-up. Specifically, our first aim, as part of the search to prove the main hypothesis (the second aim), was to examine whether lower levels of social support increased the risk of cognitive frailty among older people during the subsequent year. As our main objective, the second aim was to examine the main hypothesis that psychological distress meditated associations of social support with cognitive frailty.

Methods

Study design and participants

SREHC is a longitudinal study of older people behavior and health in rural Shandong, China. We used stratified multistage sampling to select our participants [18]. To begin this process, all counties of Shandong province were categorized into three levels (low, medium, and high) based on the GDP per capita in 2018. The second step was to select one rural county randomly in each level, and Rushan, Qufu, and Laoling were selected as our study sites. Once the county was chosen, five townships were chosen from each aforesaid county randomly. Third, four communities/villages were chosen from each township randomly. In each community/village, we chose individuals aged 60 years or over using village resident registry randomly. A total of 3243 respondents aged 60+ without a clinical diagnosis of dementia and psychiatric diseases participated the baseline survey from May 2019 to June 2019. Of the 3243 respondents at baseline, 2785 participated in the follow-up survey from August 2020 to September 2020, with a follow-up rate of 85.88%. To ensure quality, both the two surveys were conducted by the same group of trained master public health students using the same questionnaires face-to-face. Training was supervised by our principal investigator, and all questionnaires were double-checked by our quality group. Our trained students read the questionnaires to the poor vision of older individuals. Before each survey, we obtained the written informed consents from each respondents stating the study purposes, value, methods, and potential risks. For illiterate older people, in addition to obtaining their verbal consent, we also require their legally/kin authorized representative to provide a proxy written informed consent. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (approval No. 20181228) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cognitive frailty

According to the definition from I.A.N.A and I.A.G.G, respondents who had the co-existence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment were classified as having cognitive frailty in this study. Specifically, cognitive impairment was assessed by the Chinese version of the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [19]. MMSE has been widely used in the assessment of cognitive function level in older adults and has excellent reliability and validity [20]. The cut-off values of the MMSE for cognitive impairment according to educational level were ≤ 17 for the uneducated, ≤ 20 for the primary school educated, ≤ 22 for those accepted the junior high school, and ≤ 24 for those university or above, respectively [13]. Most of the measures of cognitive frailty use Fried frailty phenotype [21, 22] because it is more suitable for an immediate identification of non-disabled elders at risk of negative events. Thus, in our study, frailty was measured by frailty phenotype criteria, which was proposed and validated by Fried et al. [23]. Frailty phenotype consists of 5 items: shrinking (unintentional weight loss), weakness (grip strength), self-reported exhaustion, slowness (a walking time of 15 ft adjusted by gender and height), and low activity. Older people with 3-5 criteria were considered frail.

Social support

We adopted the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) [24] to measure social support. The SSRS is a 10-item self-reported scale composed of three parts: subjective support, objective support, and support utilization. Subjective support reflects perceived social support that individuals feel understood, supported, or helped by others. Objective support represents the actual support that individuals received, such as the financial support and the practical assistance. The utilization of support reflects the degree of social support used, such as individuals how to seek and get actual help when in need. The SSRS has been shown a reliability and validity measure in China [25, 26], The total score of SSRS ranges from 12 to 66, with higher scores indicate higher levels of social support.

Psychological distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was adopted to identify the non-specific psychological distress in this study, including depression and anxiety disorders [27, 28]. The K10 has been confirmed to have high reliability and validity in China [17, 29]. It contains 10-item and each item is assessed by using a 5-point Likert-type from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all the time). The possible score ranges from 10 to 50, with a higher score indicating higher levels of psychological distress.

Potential confounders

We identified potential confounders for social support and cognitive frailty based on the previous studies [12, 30, 31]. Potential confounders included socio-demographic characteristics, life behaviors, and health status. Socio-demographic was measured by sex, age, education, marital status, and economic status (household income per capita, Quartile 1 was the poorest and Quartile 4 was the richest). Life behaviors included smoking status (current vs. never/past), and alcohol drinking status (current vs. never/past). Health status included chronic conditions, and functional disability. Functional disability was measured by activity of daily living (ADL), including bathing, dressing, using the toilet, continence, transferring and eating.

Analytical strategy

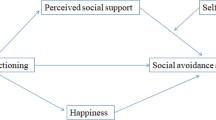

We used Chi-square tests for dichotomous variables and student t-tests for continuous variables to compare social support, psychological distress, and individual characteristics between participants with and without a cognitive frailty status at baseline survey. Path analyses with logistic function were performed to examine the direct effects of social support (predictors) on subsequent cognitive frailty (outcome) at 1-year follow-up and the mediating role of psychological distress (mediator) in this link. Both the outcome variable and mediator were measured at the 1-year follow up, and the focal parameters were labeled in Fig. 1. Specifically, we were interested in: (1) the path coefficient from social support to psychological distress at the follow-up (coefficient a), (2) the path coefficient from psychological distress at the follow-up to subsequent cognitive frailty (coefficient b), and (3) the path coefficient from social support to subsequent cognitive frailty with mediator (coefficient c′) and without mediator (coefficient c). We conducted both unadjusted and adjusted mediation models. The mediation effect was quantified as a*b [32, 33]. We also used a bootstrapping strategy resampled 5000 times to estimate the bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals to test the indirect effects. Path analyses were performed using Mplus 8.3 with robust maximum likelihood estimation method, and all other analyses were performed using Stata 14.2.

Hypothesized mediation models. Path a, the coefficient from social support to psychological distress at the follow up; path b, the coefficient from psychological distress at the follow up to subsequent cognitive frailty; path c, the coefficient from social support to subsequent cognitive frailty without psychological distress; path c’, the coefficient from social support to subsequent cognitive frailty with psychological distress

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the respondents according to cognitive frailty at baseline. Of the 2785 respondents, the average age was 69 years and most of the older adults were female (63.55%), illiterate (41.80%), and married (75.04%). At baseline, 6.71% of participants had cognitive frailty. At 1-year follow-up, the rates of cognitive frailty were 7.47%. Participants with cognitive frailty scored significantly higher on K10 (22.41 ± 9.19 vs. 16.22 ± 7.12, t = − 11.23, P < 0.001) and lower on social support (39.07 ± 7.07 vs. 43.39 ± 6.11, t = 9.23, P < 0.001) than those participants without cognitive frailty at baseline, respectively.

Table 2 presents the unstandardized path coefficients (a, b, c’, and c) of subsequent cognitive frailty in relation to social support mediated by psychological distress. The path coefficients related to binary outcomes were presented in log-odds unit. In the unadjusted models, social support was negatively associated with psychological distress (a path in the unadjusted model: β = − 0.176, 95% CI = − 0.225 to − 0.136, P < 0.001) and was negatively associated with cognitive frailty (c path in the unadjusted model: β = − 0.080, 95% CI = − 0.100 to − 0.061, P < 0.001). The effect of social support on cognitive frailty was attenuated after adjusting for psychological distress (c’ path in the unadjusted model: β = − 0.067, 95% CI = − 0.088 to − 0.047, P < 0.001). Univariate analyses showed that the log-odd of cognitive frailty was significantly higher in older people who were having lower social support score. Both a*b and c’ were negative and significant when predicting from social support. A partial mediation relationship was supported for cognitive frailty, with a ratio of a*b/(a*b + c’) was 18.29%.

After controlling for sex, age, education, marital status, economic status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, chronic conditions, ADL, and cognitive frailty at baseline, we found that social support was negatively associated with cognitive frailty (path c in the adjusted model: β = − 0.040, 95% CI = − 0.064 to − 0.016, P < 0.001). When further adjusting for baseline psychological distress, social support was also negatively associated with psychological distress (path a in the adjusted model: β = − 0.098, 95% CI = − 0.137 to − 0.066, P < 0.001), and the direct effect of social support on cognitive frailty (coefficient c’) was reduced (c’ path in the adjusted model: β = − 0.028, 95% CI = − 0.053 to − 0.007, P < 0.001), which suggested social support played protective roles in psychological health and cognitive frailty. All path coefficients including a, b, c’ and c were statistically significant when predicting subsequent cognitive frailty from social support (the adjusted models in Table 2), suggesting that the protective effect of social support on cognitive decline may be mediated by psychological pathway. Specifically, the magnitude of direct effects of low social support on cognitive frailty changed from c’ = − 0.067 to − 0.028. The magnitude of mediation effects from social support to cognitive frailty via psychological distress changed from a*b = − 0.015 to − 0.009, and the ratio of a*b/(a*b + c’) was 24.32%. These results suggested that psychological distress partially mediated the relationship between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty, which was further confirmed by Bootstrapping tests. The results from Bootstrapping test showed that the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect and direct effect did not span zero, indicating both the indirect effect and direct effect were statistically significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively examine the association of social support with subsequent cognitive frailty in a sample of rural Chinese older adults, as well as the mediating role of psychological distress in this process. There are two key findings. First, social support at baseline was significantly associated with decreased risk of subsequent psychological distress and cognitive frailty over 1-year follow-up. Second, the association of social support with cognitive frailty was partially mediated by psychological distress.

In this study, we also provided evidence about the prevalence of the cognitive frailty in rural China. We found the prevalence of cognitive frailty among rural Chinese older adults was approximately 7%, which was in accordance with previous studies using a similar definition in measurements (i.e. physical frailty was defined by phenotype criteria and cognitive impairment was defined by the MMSE) [30, 34]. However, one study using the data from the China Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Study reported 2.3% of the prevalence of cognitive frailty, which is lower than our current study [35]. A possible explanation is weakness, as one of the important items in the measurement of frailty criteria, is not included in that study, which may underestimate the prevalence. Liu et al. [36] found that the prevalence of cognitive frailty is 13.3%, which is higher than the current study. One possible explanation is that Liu et al. included an older age group (≥ 65; mean age: 73) than our study. Previous studies and our research all suggest that cognitive frailty in Chinese older adults is not uncommon.

Social support is believed to be an important determinant of healthy ageing. A considerable body of epidemiological research has documented the health benefits from social support, such as lower mortality risks, better psychological and physical health outcomes [37,38,39]. The association between social support and cognitive frailty has been shown by a handful of cross-sectional studies [12, 13]. For example, in a study of 815 older adults aged 60 years and above in Malaysia, Malek et al. found that social support is significantly associated with decreased risk for cognitive frailty (β = − 0.021, P < 0.001) [12]. To our knowledge, there are no prospective studies that have specifically examined the association between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty among older people. In the current study, we found the rates of subsequent cognitive frailty over 1-year follow-up increased with lower social support (path c and c’). Social support has been considered as a trait factor that has positive consequences for health and well-being by providing people with access to various tangible, health-enhancing resources, including, but not limited to, esteem, control, and connection [40]. These psychological resources have been found to be particularly beneficial in helping people to cope with a range of challenges, such as depression and anxiety, which in turn can affect cognitive frailty. Our finding highlights again the importance of assessing and intervening in social support for older people because it is a modifiable predictor for cognitive frailty.

Our mediation analysis showed that the association between social support and cognitive frailty was mediated by psychological distress, which could explain the longitudinal association between social support and cognitive frailty in part. Specifically, older people with higher levels of social support were associated with less psychological distress (path a), which, in turn, lead to attenuated odds of cognitive frailty (path b). This suggests that people with lower social support have more likelihoods of cognitive frailty in part because they have worse psychological health. There is substantial evidence that those with higher social support have better psychological health than those with less social support [14, 41,42,43,44]. For example, Bai et al. reported social support does not promote the physical health of the Chinese elderly in rural areas, but it has a significant positive impact on their mental health [41]. Higher levels of social support mean meaningful interpersonal relations, Yang et al. found meaningful interpersonal relations may directly reduce psychological stress levels and in turn provide positive psychological implications such as enhancement of endocrine and immune functioning [45]. However, few studies have focused on the relationships between psychological factors and cognitive frailty. Only in a recent cross-sectional survey, the authors found mood disorder symptoms are strongly associated with cognitive frailty among community-dwelling people aged 60 years and over [6]. This is the first study to report psychological distress as a mediator in relationship between social support and subsequent cognitive frailty among Chinese older people. Our findings underpin the conceptual model of social relationships proposed by Berkman [46]. The model hypothesizes that health is impacted by social relationships through a series of causal processes that begin at the macro-social level (upstream factors) to micro-psychobiological processes (downstream factors). In the social network framework, psychological factors such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, depression, psychological distress, and sense of well-being represent some of the “downstream” pathways linking social relationships to health. Our study provides the evidence that social support as one of the “downstream factors” of social relationship can affect older adults’ cognitive frailty by psychological pathway (i.e., psychological distress). Psychological distress may serve as a negative form of the robust positive effects of social support on cognitive frailty in this population. Also, this finding suggests the importance of screening for psychological distress and providing strategies to mitigate the effects of poor mental health in later life. Further neurobiological and behavioral research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms between social support, psychological distress, and cognitive frailty among older people.

The current study has several strengths. The first strength is the longitudinal design that allows us to look at the association between social support and cognitive frailty over time. The second strength is that this study was the first to test the mediating role of psychological distress in the relation between social support and cognitive frailty among older people. The third strength is that multiple potential confounders such as socio-demographic, health behavioral (smoking and alcohol drinking), health (chronic conditions and ADL disability), and prior cognitive frailty status were controlled when examining the link between social support and cognitive frailty. Despite the strengths, our study is limited in several ways. First, the relatively small number of observations who developed cognitive frailty at the one year of follow up may cause small-sample bias. Second, the key variables (such as psychological distress) in this study, were based on self-reported data, which might lead to recall bias. Third, only one mediation variable was used in this study, and more potential paths need to be explored in the future. Finally, the current work was conducted only in rural areas, thus the results obtained from this study may be limited in urban settings, and future research should include urban areas for comparison.

Conclusions and implications

Our study provides evidence that low social support is associated with increased rates of subsequent cognitive frailty among older people over 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, the effect of social support on cognitive frailty is partially mediated through psychological distress. These findings may have several important clinical and public health policy implications. First, the findings underscore the importance of screening older people at risk of cognitive frailty by assessing psychological distress. Second, the findings underline the need for clinicians to be alert to older people who report psychological distress, and it is important to help these older people getting appropriate treatment for their psychological distress. Third, social support is also important for older people to prevent cognitive frailty because it is a modifiable predictor, and improving the levels of social support is also a main way to effectively reduce psychological pressure for rural older people, such as organizing group activities and providing rural older service center.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in the current study are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- I.A.N.A:

-

International Academy on Nutrition and Aging

- I.A.G.G:

-

International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics

- SREHC:

-

Shandong Rural Elderly Health Cohort

- MMSE:

-

Mini Mental Status Examination

- SSRS:

-

Social Support Rating Scale

- K10:

-

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale

- ADL:

-

Activity of Daily Living

References

Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Tsutsumimoto K, Anan Y, et al. Combined prevalence of frailty and mild cognitive impairment in a population of elderly Japanese people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(7):518–24.

Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, van Kan GA, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.a.N.a./I.a.G.G.) international consensus group. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(9):726–34.

Zheng LF, Li GC, Gao DW, Wang S, Meng XF, Wang C, et al. Cognitive frailty as a predictor of dementia among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;87:103997.

Bu ZH, Huang AL, Xue MT, Li QY, Bai YM, Xu GH. Cognitive frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain and Behavior. 2020;11(1):e01926.

Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Feng L, Yap KB, Ng TP. Cognitive frailty and adverse health outcomes: findings from the Singapore longitudinal ageing studies (SLAS). J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):252–8.

De Roeck EE, van der Vorst A, Engelborghs S, GAR Z, Dierckx E, Consortium DS. Exploring cognitive frailty: prevalence and associations with other frailty domains in older people with different degrees of cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2020;66(1):55–64.

Ruan QW, Yu ZW, Chen M, Bao ZJ, Li J, He W. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:1–10.

Catabay CJ, Stockman JK, Campbell JC, Tsuyuki K. Perceived stress and mental health: the mediating roles of social support and resilience among black women exposed to sexual violence. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:143–9.

Kelly ME, Duff H, Kelly S, McHugh Power JE, Brennan S, Lawlor BA, et al. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):259.

Li J, Zhao DD, Dong B, Yu DD, Ren QQ, Chen J, et al. Frailty index and its associations with self-neglect, social support and sociodemographic characteristics among older adults in rural China. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(7):987–96.

Noguchi T, Nojima I, Inoue-Hirakawa T, Sugiura H. The association between social support sources and cognitive function among community-dwelling older adults: a one-year prospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4228.

Malek Rivan NF, Shahar S, Rajab NF, Singh DKA, Din NC, Hazlina M, et al. Cognitive frailty among Malaysian older adults: baseline findings from the LRGS TUA cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1343–52.

Katayama O, Lee S, Bae S, Makino K, Shinkai Y, Chiba I, et al. Lifestyle activity patterns related to physical frailty and cognitive impairment in Urban Community-dwelling older adults in Japan. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;22(3):583–9.

Gronning K, Espnes GA, Nguyen C, Rodrigues AMF, Gregorio MJ, Sousa R, et al. Psychological distress in elderly people is associated with diet, wellbeing, health status, social support and physical functioning- a HUNT3 study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):205.

Mordeno IG, Badawi JK, Marcera JL, Ramos JM, Cada PB. Psychological distress and perceived threat serially mediate the relationship between exposure to violence and political exclusionist attitude. Curr Psychol. 2020:1–9. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-020-01170-9.

Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, Namdar P, Griffiths MD, Ahorsu DK, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100307.

Jing ZY, Li J, Wang Y, Ding LL, Tang X, Feng YJ, et al. The mediating effect of psychological distress on cognitive function and physical frailty among the elderly: evidence from rural Shandong, China. J Affect Disord. 2020;268:88–94.

Wang Y, Fu P, Li J, Jing Z, Wang Q, Zhao D, et al. Changes in psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults: the contribution of frailty transitions and multimorbidity. Age Ageing. 2021;50(4):1011–18

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Fang SC, Huang CJ, Wu YL, Wu PY, Tsai PS. Effects of napping on cognitive function modulation in elderly adults with a morning chronotype: a nationwide survey. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(5):e12724.

Rivan NFM, Singh DKA, Shahar S, Wen GJ, Rajab NF, Din NC, et al. Cognitive frailty is a robust predictor of falls, injuries, and disability among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):593.

Vatanabe IP, Pedroso RV, Teles RHG, Ribeiro JC, Manzine PR, Pott-Junior H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on cognitive frailty in community-dwelling older adults: risk and associated factors. Aging Ment Health. 2021;1-13.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol a-Biol. 2001;56(3):M146–M56.

Xiao SY. Social supporting scale: the theoretical foundation and research applications (in Chinese). J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;4(2):98–100.

Lin J, Su Y, Lv X, Liu Q, Wang G, Wei J, et al. Perceived stressfulness mediates the effects of subjective social support and negative coping style on suicide risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;265(1):32–8.

Jin Y, Si H, Qiao X, Tian X, Liu X, Xue QL, et al. Relationship between frailty and depression among community-dwelling older adults: the mediating and moderating role of social support. Gerontologist. 2020;60(8):1466–75.

Kessler R, Barker P, Colpe L, Epstein J, Zaslavsky A. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76.

Arvidsdotter T, Marklund B, Kylen S, Taft C, Ekman I. Understanding persons with psychological distress in primary health care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(4):687–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12289.

Zhou CC, Chu J, Wang T. Reliability and validity of 10-item Kessler scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of mental health status of Chinese population (in Chinese). Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2008;17(6):627–9.

Xie B, Ma C, Chen Y, Wang J. Prevalence and risk factors of the co-occurrence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;29(1):294–303.

Yeh SCJ, Liu YY. Influence of social support on cognitive function in the elderly. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):9.

Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115.

Liu X, Yang Y, Liu ZZ, Jia CX. Longitudinal associations of nightmare frequency and nightmare distress with suicidal behavior in adolescents: mediating role of depressive symptoms. Sleep. 2020;44(1):zsaa130.

Majnaric LT, Bekic S, Babic F, Pusztova L, Paralic J. Cluster analysis of the associations among physical frailty, cognitive impairment and mental disorders. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924281.

Ma L, Zhang L, Sun F, Li Y, Tang Z. Cognitive function in Prefrail and frail community-dwelling older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):53.

Liu LK, Chen CH, Lee WJ, Wu YH, Hwang AC, Lin MH, et al. Cognitive frailty and its association with all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan: results from I-Lan longitudinal aging study. Rejuvenation Res. 2018;21(6):510–7.

Weiss-Faratci N, Lurie I, Neumark Y, Malowany M, Cohen G, Benyamini Y, et al. Perceived social support at different times after myocardial infarction and long-term mortality risk: a prospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(6):S1047279716300758.

Muramatsu N, Yin H, Hedeker D. Functional declines, social support, and mental health in the elderly: does living in a state supportive of home and community-based services make a difference? Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1050–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.005.

Tao Y, Yu S. The influence of social support on the physical and mental health of the rural elderly (in Chinese). Popul Econ. 2014;3:6–17.

Lu J, Zhang C, Xue Y, Mao D, Zheng X, Wu S, et al. Moderating effect of social support on depression and health promoting lifestyle for Chinese empty nesters: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:495–508.

Bai YL, Bian F, Zhang LX, Cao YM. The impact of social support on the health of the rural elderly in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2004.

Matud MP, Garcia MC. Psychological distress and social functioning in elderly Spanish people: a gender analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):341.

Milner A, Krnjacki L, Butterworth P, LaMontagne AD. The role of social support in protecting mental health when employed and unemployed: a longitudinal fixed-effects analysis using 12 annual waves of the HILDA cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:20–6.

Lakey B, Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: a new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. 2011;118(3):482–95.

Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(3):578–83.

Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–57.

Acknowledgments

We thank the officials of health agencies, all participants and staffs at the study sites for their cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 71774104, 71974117); and the China Medical Board (grant numbers 16-257), Cheeloo Youth Scholar Grant, and Shandong University (Grant Numbers IFYT1810, 2012DX006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing and Funding Acquisition. Y.W.: Writing - original draft and formal analysis. J.L., P.F., Z.J., and D.Z.: Acquired the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before each survey, we obtained the written informed consents from each respondents stating the study purposes, value, methods, and potential risks. For illiterate older people, in addition to obtaining their verbal consent, we also require their legally/kin authorized representative to provide a proxy written informed consent. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (approval No. 20181228) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Li, J., Fu, P. et al. Social support and subsequent cognitive frailty during a 1-year follow-up of older people: the mediating role of psychological distress. BMC Geriatr 22, 162 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02839-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02839-5