Abstract

Background

Malnutrition negatively impacts on health, quality of life and disease outcomes in older adults. The reported factors associated with, and determinants of malnutrition, are inconsistent between studies. These factors may vary according to differences in rate of ageing. This review critically examines the evidence for the most frequently reported sociodemographic factors and determinants of malnutrition and identifies differences according to rates of ageing.

Methods

A systematic search of the PubMed Central and Embase databases was conducted in April 2019 to identify papers on ageing and poor nutritional status. Numerous factors were identified, including factors from demographic, food intake, lifestyle, social, physical functioning, psychological and disease-related domains. Where possible, community-dwelling populations assessed within the included studies (N = 68) were categorised according to their ageing rate: ‘successful’, ‘usual’ or ‘accelerated’.

Results

Low education level and unmarried status appear to be more frequently associated with malnutrition within the successful ageing category. Indicators of declining mobility and function are associated with malnutrition and increase in severity across the ageing categories. Falls and hospitalisation are associated with malnutrition irrespective of rate of ageing. Factors associated with malnutrition from the food intake, social and disease-related domains increase in severity in the accelerated ageing category. Having a cognitive impairment appears to be a determinant of malnutrition in successfully ageing populations whilst dementia is reported to be associated with malnutrition within usual and accelerated ageing populations.

Conclusions

This review summarises the factors associated with malnutrition and malnutrition risk reported in community-dwelling older adults focusing on differences identified according to rate of ageing. As the rate of ageing speeds up, an increasing number of factors are reported within the food intake, social and disease-related domains; these factors increase in severity in the accelerated ageing category. Knowledge of the specific factors and determinants associated with malnutrition according to older adults’ ageing rate could contribute to the identification and prevention of malnutrition. As most studies included in this review were cross-sectional, longitudinal studies and meta-analyses comprehensively assessing potential contributory factors are required to establish the true determinants of malnutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Improvements in healthcare, along with the development of medical treatments and vaccines, have increased life expectancy worldwide [1]. This has radically changed the global population demographic, with the proportion of older adults increasing, especially in developed countries [2]. Within Europe, 19.2% of the population were aged 65 years or over in 2016, with a projected increase to 29.1% by 2080 [3]. Considerable challenges arise with this increasing ageing population, among them promoting good health and well-being within this group so that they can live independently in the community for as long as possible [4].

One such challenge among older adults living in the community is risk of malnutrition and more specifically undernutrition (hereafter referred to as malnutrition) [5, 6]. Older adults are at increased risk of developing malnutrition due to natural age-related changes [7], namely, unfavourable changes in body composition, increased requirements for protein and certain micronutrients, alterations in appetite and declining sensory function. Left untreated, malnutrition can detrimentally affect cognitive and physical function, both of which can lead to loss of independence, increased risk of disease and poorer health outcomes [8,9,10,11]. Moreover, malnutrition is a complex multifactorial process, with many other components, such as, lifestyle, financial, social, psychological, presence of disease and medication use, known to contribute [12]. Within the published literature, there is little consistency between previously reported factors associated with malnutrition. In developed countries, malnutrition prevalence differs across community and healthcare settings depending on the individual’s characteristics, and the tools used to identify malnutrition. The greatest number of malnourished older adults in the UK is in the community setting (accounting for approximately 5% of the older population) [13, 14]. Community-dwelling older adults are a heterogeneous group who may experience remarkable differences in their ageing trajectory; namely, successful, usual or accelerated rates [15]. Successfully ageing older adults have few health conditions, are independent, rarely use healthcare services and their years of ill health are condensed into the end-of-life. Usually ageing older adults typically maintain their functional ability and independence but have health conditions and require frequent visits to their general practitioner (GP) to maintain their health status. Those experiencing an accelerated rate of ageing are frailer and more dependent than expected for their age, have multiple chronic diseases or experience rapid disease progression, and are frequent users of healthcare services [15].

With the global increase in life expectancy, more attention is being drawn to different rates of ageing. In particular, the concept of successful ageing is now acknowledged to be an important area of research. Nonetheless, whilst there is general agreement on the characteristics typical of a person ageing at a successful rate, to date, there is no consensus on how this concept should be defined. One of the most used definitions for successful ageing is someone who is ‘free of disease and disability, has a high physical and cognitive functioning ability and has an active engagement with life in general’ [16]. Rate of ageing can be influenced both positively and negatively by lifestyle, diet, psychological, psychosocial and disease related factors. Higher rates of physical activity throughout life are strongly linked to successful ageing [17, 18]. Older adults who self-report good health and no pain are more likely to age successfully than those that don’t [19]. Older adults experiencing different ageing trajectories may have different determinants of malnutrition which are specific to their rate of ageing.

Malnutrition in older adults is often under-recognised and poorly managed [20]. This can be attributed to the fact that it is a slow progressing condition and, therefore, its early signs and symptoms are not easily recognised either by affected individuals [21] or healthcare professionals (HCPs) [22]. Additionally, a universal definition and agreed diagnostic criteria have only recently emerged [20, 23, 24]. With the aim of achieving consensus on the definition of malnutrition, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) stated (in 2015) that the following definition of malnutrition was generally accepted; “a state resulting from lack of uptake or intake of nutrition leading to altered body composition (decreased FFM) and body cell mass leading to diminished physical and mental function and impaired clinical outcome from disease” [25]. Furthermore, a global consensus for the diagnosis of malnutrition has recently (2019) been published based on a two-step approach; screening for risk of malnutrition using a validated tool, followed by assessment of the condition to provide a diagnosis of malnutrition and to grade its severity [26, 27].

Understanding and identifying factors that lead to malnutrition is critical for developing interventions aimed at preventing or delaying disability in older adults. This is particularly important in the community, where although prevalence is low, the greatest number of at-risk individuals reside [14, 28]. Community-dwelling older adults are a heterogeneous group; thus, the factors related to, or determinants of, malnutrition may vary according to individual differences in the rate of ageing. Potential differences in determinants of, and factors related to malnutrition according to differences in ageing rates may contribute to the heterogeneity between currently published studies. The aim of this review, therefore, is to summarise the current evidence relating to the sociodemographic factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition and malnutrition risk in community-dwelling older populations and, to explore potential differences according to different rates of ageing [15].

Methods

Search strategy

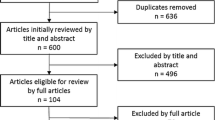

Two independent systematic searches (Search 1, LAB; Search 2, KL, ML, MGB) of PubMed Central and Embase databases were conducted in April 2019 to identify relevant papers on ageing and poor nutritional status. Duplicates were excluded (LAB and KL), and titles examined to assess suitability for inclusion (LAB and ML). Studies examining the sociodemographic factors associated with, or determinants of, malnutrition were included. The key search terms were as follows: the primary outcome (protein-energy malnutrition, malnutrition, undernutrition, weight loss, nutritional status); the population sub-group (elderly, older adults, ageing, aging); and the exposure (determinants, predictors, risk factors). Figure 1 shows the exact search terms used.

Inclusion criteria

Studies with populations with mean age > 65 years, majority community-dwelling (> 80%), and conducted in Western populations (specifically European, North American, Canadian, Australian and New-Zealanders) were selected for consideration. Studies containing populations from multiple countries were only included if the majority of the population came from the specified Western countries. As the standardised criteria for diagnosing malnutrition were only published in 2019 [26, 27], papers using any definition of malnutrition arising from use of screening tools, specific BMI cut-offs or weight loss percentages were considered for inclusion. Only papers which were published since 2000, peer-reviewed, available in full-text, written in English, conducted on humans and in which the study authors completed multivariate statistical analysis were considered for inclusion. As the main aim of this review was to assess the sociodemographic factors associated with malnutrition according to a population’s rate of ageing, studies examining a combination of biochemical or nutritional factors in addition to sociodemographic factors were excluded [29,30,31].

Study selection

Abstracts were screened for inclusion by two authors independently (LAB and ML). If a study appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, full text articles were read and analysed for inclusion by two authors working independently (LAB and MGB). Final inclusion was decided by consensus discussion with a senior researcher working on the topic of community malnutrition (PDC).

Data synthesis

Selected full-text articles were read in full and the investigated factors categorised into domains. Factors suggested as being associated with malnutrition or as determinants of malnutrition were categorised under nine known domains: demographic, food intake, oral, lifestyle, social, economic, physical functioning, psychological and disease-related [32]. For the purposes of this review, poverty was included in the social domain and both edentulousness and chewing difficulties included in the food intake domain. Factors reported within each domain are summarised in Table 1. Where possible, study populations were categorised into successful, usual or accelerated rate of ageing groups according to the criteria suggested by Keller et al. (2007), as summarised below [15] (Fig. 2).

-

Successful ageing: predominantly functionally independent (> 60%), not frail (< 40%), low prevalence of polypharmacy (< 40%), and low prevalence of multi-morbidity (< 40%).

-

Usual ageing: predominantly functionally independent (> 60%), not frail (< 40%), a high proportion regularly attending a GP (> 50%), high prevalence of multi-morbidity (> 50%) and polypharmacy (> 50%).

-

Accelerated ageing: predominantly frail (> 60%), functionally dependent (> 60%), users of home-care services (> 40%), and a high proportion was recently hospitalised (> 50%).

For each of the parameters listed above, any measure or tool or definition used by a particular study was deemed acceptable. In order for study populations to be categorised, information had to be available for at least two of the above criteria. Study populations were placed between two categories if there was insufficient information to differentiate which specific category the population should be placed in.

Results

Search results

The initial database search yielded 21,326 papers once duplicates were deleted. All papers were considered for inclusion; reasons for exclusion are outlined in Fig. 3. The most common reasons for exclusion were studies conducted in non-Western populations, younger populations (mean < 65 years), populations with a specific disease or condition (e.g., Parkinson’s disease), studies whose primary focus was not malnutrition and studies completed in hospital, residential care, or rehabilitation settings. A total of 68 papers met the final inclusion criteria (Fig. 3).

The articles included were heterogeneous in study design (Table 2). Studies were predominantly of cross-sectional (N = 54) or longitudinal design (N = 11). There were two systematic reviews of observational studies and one meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sample size of the studies ranged from 49 to 15,669 participants. The majority of included studies were conducted within European countries.

Categorisation of studies according to rate of ageing

Nine studies were classified as ageing at a usual rate [35, 36, 39, 49, 63, 66, 70, 84, 99]. Three studies were classified as ageing successfully and five studies were categorised as ageing at an accelerated rate. Six studies were placed between the successful and usual ageing groups [34, 41, 42, 45, 68, 100] and five studies were placed between the usual and accelerated ageing categories [38, 44, 53, 77, 93]. In order to include as many studies as possible in our results, studies classed within the usual to successful ageing category were collapsed into the successful ageing category [21, 85, 87] whilst studies within the usual to accelerated category were collapsed into the accelerated ageing category [40, 46, 94,95,96] (Fig. 2). Forty studies remained uncategorised so were omitted from the synthesis of studies by ageing rate; however, the details of each of these studies are described in Table 2. Primary reasons for not categorising studies included lack of information on presence of chronic diseases, polypharmacy, functionality, frailty or use of social or medical services not being provided or that the study included multiple cohorts (details of all studies included in this review are within Table 2).

Factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition

Factors in the demographic and disease-related domains were most-commonly examined (63 and 54 studies respectively), followed by the social (50 studies), psychological and physical functioning domains (46 studies each) (Table 2). Factors under the food intake and lifestyle domains were the least well studied (32 and 20 studies respectively). The factors most-commonly reported to be associated with malnutrition were within the demographic (41 studies), disease-related (34 studies), physical functioning (30 studies) and psychological (30 studies) domains. Domains less commonly reported as associated with malnutrition were the social (27 studies), food intake (23 studies) and lifestyle (7 studies). The evidence for individual factors within each domain is critically considered.

The frequency of factors reported as associated with malnutrition according to the rate of ageing category is presented in Table 3. In this review, demographic factors such as being female (successful, N = 2; usual, N = 1; accelerated, N = 1) and increasing age (successful, N = 2; usual, N = 3; accelerated, N = 1) were commonly reported as associated with malnutrition/malnutrition risk across all ageing rate categories. Other demographic (unmarried status (N = 4) [42, 45, 85, 100] and a low education level (N = 2) [34, 68]) and physical functioning factors were more commonly reported within the successful ageing category compared to the other ageing rate categories. Factors within the food intake and disease-related domains were most-commonly reported in older adults who are ageing at an accelerated rate.

This review found that factors reported to be associated with malnutrition from the food intake domain increased in frequency and severity across the three ageing categories (successful, usual, accelerated). Food insecurity was reported as a risk factor in the successfully ageing category [42], choosing foods that were easy to chew was a risk factor in the usual ageing category [39], whilst difficulties eating and eating dependency were associated with malnutrition risk in the accelerated ageing category [77]. Having a poor or reduced appetite is reported as being associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk across all categories of ageing rate [39, 44, 77, 87].

Within this review, lifestyle factors were rarely reported as being associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in any of the ageing categories. Lack of physical activity was reported once in both the successfully [68] and accelerated [46] ageing categories. Alcohol use was reported as being associated with a lower risk of malnutrition once within the usual ageing category [49]. Smoking was reported to be associated with malnutrition in one study from the accelerated ageing category [46].

Cognitive impairment, a factor within the psychological domain was reported as being associated with malnutrition by one study in the successful ageing category [85], whilst dementia was reported as associated with malnutrition risk in both the usual (N = 1) [36] and accelerated (N = 2) [53, 94] ageing categories. Depressive symptoms were reported in the successful ageing (N = 2) [34, 45], usual ageing (N = 3) [35, 36, 49] and accelerated ageing (N = 2) [38, 53] categories.

Indicators of declining mobility (difficulty walking 100 m and difficulty climbing a flight of stairs) were reported in the successful ageing category only (N = 2) [85, 87]. Factors indicative of physical dependency (being unable to go outside) were reported in one study from the accelerated ageing category [46]. Falls were reported to be associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in the successful ageing (N = 1) [85] and accelerated ageing (N = 1) [96] categories.

Living with others was associated with reduced risk of developing malnutrition in the successful ageing category (N = 1) [45], whilst living alone was associated with increased risk of malnutrition risk in the usual ageing category (N = 2) [35, 39]. Social support was reported to be associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in both the successful (N = 2) [85, 100] and usual (N = 2) [35, 99] ageing categories.

This review found factors from the disease-related domain were commonly reported across all ageing rate categories but increased in severity as the ageing rate progressed into the accelerated ageing category. Recent hospitalisation was reported in the successful (N = 1) [85] and accelerated (N = 2) [94, 96] ageing categories. Factors such as multi-morbidity were more commonly reported in the successful ageing category (N = 2) (N = 0, usual ageing category, N = 1, accelerated ageing category) whilst individual diseases such as cancer and osteoporosis (N = 1) [46] and extended hospital stays (N = 1) [96] were reported in the accelerated ageing category.

Discussion

This review provides a summary of the factors associated with malnutrition and malnutrition risk reported in community-dwelling older adults with an emphasis on differences identified according to rate of ageing [15]. This novel approach has found that as the rate of ageing accelerates, an increasing number of factors are reported within the food intake, social and disease-related domains; and these factors increase in severity in the accelerated ageing category. Within the usual and accelerated ageing categories, dementia is reported to be associated whilst cognitive impairment appears in the successful ageing category. Indicators of declining mobility and function are associated with malnutrition and these indicators increase in severity across the ageing categories. Within the successful ageing category, demographic factors such as low education level and unmarried status appear to be most important. Factors such as hospitalisation and falls appear to be relevant regardless of rate of ageing.

The findings presented in this paper contribute to our understanding of the factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition in older adults and may explain differences in factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition reported in previously published studies. Standardised criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition were only published as recently as 2019 [26, 27]. The majority of studies included in this review were published prior to this date; thus, many differing definitions of malnutrition were used. The lack of consistency between studies makes comparisons difficult; however, implementation of these 2019 criteria in future studies should help to reduce the heterogeneity.

Factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition

Demographic domain

Numerous cross-sectional studies included in this review reported no association between marital status and malnutrition [34, 37, 46, 47, 50, 51, 62, 70, 88, 93]. Conversely, other studies, including a recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, did report a relationship, whereby not being married was associated with an increased risk of developing malnutrition [33, 42, 45, 56, 73, 76, 95, 99]. This may be attributed to the fact that being married is linked to better health behaviours across life, with this effect being more pronounced in men [52]. In this review, unmarried status was frequently reported to be associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in the successful ageing category. Most of the evidence in this review suggested that level of education is not associated with malnutrition [32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 42, 45, 46, 49, 50, 54, 55, 61, 62, 66, 67, 70, 71, 73, 76, 85, 87, 88, 93, 99,100,101,102]. However, when stratified by rate of ageing, a low level of education appeared to be more commonly reported as being associated with malnutrition within the successful ageing category. These demographic factors could be playing a key role in the development of malnutrition within the successful ageing group as older adults in this category are not burdened with chronic diseases, mental or physical functional limitations to the same extent as older adults in the other ageing rate categories.

Age and female sex are reported to be associated with malnutrition and malnutrition risk across all ageing rate categories. It has been reported that females have a 45% higher chance of developing malnutrition compared to their male counterparts [72]. This could be due to a multitude of factors including the fact that globally women have longer life expectancies than men [72, 82]. Women are also more likely to experience adverse social and economic circumstances in old age [72, 103,104,105], which are themselves independently associated with increased risk of malnutrition. Within the included studies, many reported an independent association between increasing age and deteriorating nutritional status [34, 42, 43, 53, 57, 62, 63, 76, 79, 81, 83, 88, 106, 107]; conversely, a systematic review concluded there was moderate strength evidence to suggest that older age and malnutrition are not associated [32]. Furthermore, a second systematic review concluded that it is likely that frailty is driving the association seen between malnutrition and advancing age [89]. Factors within the demographic domain are frequently reported to be associated with malnutrition; however, consideration should be given as to whether these are true determinants of the condition or whether the associations seen are false positives due to frequency of assessment.

Food intake domain

Factors affecting food intake, such as the amount of food eaten or the ability to eat/feed oneself, appear to be particularly associated with malnutrition within the accelerated ageing category, compared to the other categories. This may be in line with the fact that this group comprises a sicker, and more diseased population group. The escalation in the severity of these factors across the ageing categories (from food insecurity to factors affecting food choice to having difficulty or being unable to self-feed), highlights that as older adults deteriorate in health and function, they become more vulnerable to developing malnutrition.

In this review, a reduced/poor appetite appears to be associated with malnutrition across all ageing rate categories. Reduced appetite can be a consequence of many factors known or suggested to be associated with, or determinants of, malnutrition, including depression, cognitive decline, chewing or swallowing difficulties and sensory changes [90, 108, 109]. Two systematic reviews included in this review reported that reduced appetite is associated with malnutrition with one of these reviews reporting that poor appetite was the only factor that had strong evidence to support an association with malnutrition [32, 110]. Conversely however, a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies reported no association with incident malnutrition [73]. These differences may be related to the fact most studies included in the systematic reviews and categorised by rate of ageing in this review were cross-sectional in design, whilst the meta-analysis only included longitudinal studies. In addition, variances in the way the question on appetite was asked between studies may have contributed to these differences.

Evidence surrounding the association between dental status and presence of chewing problems and malnutrition is conflicting [39, 44, 55, 61, 63, 79, 93, 110, 111]. Having no/few teeth and difficulties chewing can be detrimental to diet quality and lead to malnutrition as nutrient-dense foods (e.g., meat, fruit and vegetables) may be avoided in favour of softer, higher calorie but less nutrient-dense foods which may be easier to eat [98]. However, difficulties chewing or swallowing may also be a consequence of malnutrition as a decline in physical function is a known outcome of malnutrition which may explain the conflicting findings found amongst the cross-sectional studies included in this review [41, 44, 63, 97].

Lifestyle domain

Lifestyle factors were seldom reported across all categories of ageing rate; thus, the evidence surrounding lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption, smoking and low physical activity and malnutrition is weak. Few associations have been reported for physical activity as a protective factor [51, 56, 68] and smoking as increasing risk [33, 46] of malnutrition in cross-sectional studies. One cross-sectional study reported alcohol intake as protective against malnutrition [49]. This study was conducted in The Netherlands which is one of the lowest alcohol-consuming countries in Europe; therefore, this finding may not be applicable in countries with higher consumption rates [112]. All other included studies, including a meta-analysis and two systematic reviews, failed to report associations between alcohol consumption and malnutrition [32, 37, 46,47,48,49, 70, 73, 85, 87, 96, 110, 111, 113]. As reported in a previous systematic review [110], our review reinforces the conclusion that factors within the lifestyle domain do not appear to be determinants of malnutrition in older adults.

Social domain

Factors within the social domain, predominantly factors related to social support, were apparent within the successful and usual ageing categories, where social factors related to use of services were more prevalent amongst the accelerated ageing category, likely reflecting increased dependency among this group and subsequently, a higher need for these services. This finding is supported by two longitudinal studies which reported that meals-on-wheels use, which may be linked to reduced social (and physical) functioning, was associated with increased risk of malnutrition [40, 94]. Amongst fit, community-dwelling older adults, those with the highest levels of social vulnerability (defined using the social vulnerability index) have been reported to be more than twice as likely to die compared to their counterparts who had the lowest levels of social vulnerability [58]. In contrast, a meta-analysis has reported that living alone or receiving social support do not predict incident malnutrition [73]. These differences may be related to study design as our review is predominantly comprised of cross-sectional studies.

Physical functioning domain

Evidence surrounding a relationship between inability or difficulty completing activities of daily living (ADLs) and malnutrition is conflicting [34, 36, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 63, 71, 83, 88, 92,93,94,95, 97, 111]. A systematic review has stated there was inconclusive evidence to identify whether there was an association with malnutrition [32]. This conflicts with other studies which suggest that declining health and/or functionality can make cooking, personal transport and grocery shopping difficult; therefore, negatively affecting nutritional status [114]. Further work is required to fully understand this.

Low handgrip strength (HGS) did not appear to be associated with malnutrition across any of the rate of ageing categories. Furthermore, HGS, was reported to have no association with incident malnutrition following a meta-analysis of longitudinal cohorts [73]. Although this may seem surprising as HGS is often used as a marker for functionality and/or frailty, it may be explained by the fact that declines in physical function are a known outcome of malnutrition and, therefore, low HGS is likely a consequence as opposed to a determinant of the condition. As such, low HGS may be a useful indicator of those who are severely malnourished as opposed to those exhibiting early signs or risk of developing malnutrition.

Falls among older adults, can be an indicator of declining cognition or onset of frailty [91, 115] and can result in fractures and hospitalisation, known risk factors for nutritional decline [116, 117]. Increased risk of falling appears to be associated with malnutrition in both the successful ageing and accelerated ageing groups, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between falling and malnutrition, whereby it could be a determinant of malnutrition for an older person ageing at a successful rate, initiating a rapid deterioration in health. Equally, it could be a consequence of malnutrition in an older person ageing at an accelerated rate. Adding weight to this hypothesis, a recent meta-analysis of six longitudinal studies reported no association between falls and incident malnutrition. However, this study reported that difficulty walking 100 m and difficulty climbing a flight of stairs (indicators of mobility) were determinants of incident malnutrition [73]. Indicators of declining mobility associated with malnutrition appear to increase in severity across ageing rate categories. Difficulties walking 100 m or climbing a flight of stairs appeared as associated factors in the successful ageing group whilst being unable to go outside is an associated factor in the accelerated ageing category.

Psychological domain

The prevalence of malnutrition is significantly higher among people with dementia; however, this is more likely to impact on the determinants of malnutrition in long-term care settings where dependency is higher compared to the community setting [118, 119]. Difficulties assessing whether cognitive decline is a determinant of malnutrition are compounded by the under-representation of this cohort of older adults within studies. Cognitive decline appears to be associated with malnutrition in one study in the successful ageing category, while dementia is associated with malnutrition within the usual ageing and accelerated ageing categories. It is likely that this is signifying the progressive decline in health as older adults move from ageing at a successful rate into the other less successful ageing categories.

Disease-related domain

Disease-related factors appear across all ageing categories; however, specific diseases such as cancer and osteoporosis only appear within the accelerated ageing category. Malnutrition is common among older adults with cancer, with the prevalence ranging from 30 to 85% depending on the cancer type [120]. Recent hospitalisation is the factor most likely to impact negatively on an older person’s nutritional status within the disease-related domain [32, 73, 110]. Hospitalisation appears as an important factor within the successful and accelerated ageing categories in this review. However, prolonged hospital stay (> 4 weeks) only appears as a factor within the accelerated ageing category. Similar to falls, hospitalisation is likely to have a bidirectional relationship with malnutrition, being a determinant of the condition for those ageing at a successful rate and a consequence for those within the accelerated ageing category.

Numerous studies have reported associations between poor self-rated (SR) health and malnutrition [32, 37, 42, 47, 81, 84, 88, 94, 106, 110, 121, 122] with SR health being a prevalent factor across all ageing rate categories in this review. This contrasts with a recent meta-analysis (of longitudinal studies) that reported no association between SR health and incident malnutrition [73]. Contradictory results have been reported surrounding the relationship between polypharmacy and the number of chronic diseases with malnutrition and malnutrition risk. Two systematic reviews have concluded that the evidence for polypharmacy as a factor associated with malnutrition was inconclusive and that there was moderate evidence to support no association with number of comorbidities [32, 110]. The conflicting results reported for these factors is likely due to the differing numbers of medications/diseases being used to define polypharmacy/multimorbidity between studies.

Strengths and limitations

This review used a novel approach of categorising community-dwelling older adults according to their rate of ageing (successful, usual or accelerated) and assessed whether differences occurred in the factors associated with malnutrition for each category. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has taken this approach previously. This approach may contribute to reducing the heterogeneity in factors reported to be associated with malnutrition among older adults in the community setting.

There are a number of limitations associated with the published literature on the determinants of malnutrition in older adults. Whilst 68 studies were initially identified as relevant for inclusion in this review, 40 could not be categorised according to rate of ageing due to the lack of detailed information on the characteristics of the study population provided within the published manuscripts. These studies were, therefore, omitted from the synthesis of factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition by rate of ageing. Had these manuscripts contained sufficient information to permit categorisation by rate of ageing, our results would have been strengthened or potentially different. Where possible, the current review sub-categorised the study populations from the included studies into successful, usual or accelerated ageing. It is likely that there was heterogeneity between the participants included in individual studies; however, group means were used to categorise the populations from individual papers as a whole into rate of ageing categories. Furthermore, there was variation in the parameters used in different studies, for example, number of medications to define polypharmacy and method of measuring functional independence.

The majority of studies included in this review used convenience samples, often with small sample sizes. This limits the use of the results as they cannot be extrapolated to represent the general population of community-dwelling older adults. A number of studies only investigated factors from one or two domains, thus, failing to acknowledge the multifactorial aetiology of malnutrition. Furthermore, a factor or determinant could not be identified as associated with malnutrition if it had not been included in the original study. The majority of current published literature is cross-sectional in design. Studies of longitudinal design are superior to definitively determine the factors which predict malnutrition as cross-sectional studies cannot distinguish between the causes and consequences of malnutrition. This review included only studies published in the English language and from the year 2000 onwards. The timeframe chosen was to ensure a more standardised approach to the identification of malnutrition and malnutrition risk and allowed for the identification of potential factors and determinants of malnutrition relevant to the health of older adults in the past 20 years. Nonetheless, these factors may have introduced selection bias into our results.

Conclusions

Numerous changes occur with ageing, increasing the vulnerability of older adults to developing malnutrition. Older adults are a heterogeneous group; thus, assessment of individuals’ rate of ageing could aid in identifying specific determinants for different cohorts of community-dwelling older adults. In the future, categorising community-dwelling older adults according to their rate of ageing could also be incorporated into malnutrition screening methods; this would allow for a more personalised approach to identifying malnutrition in older adults as different domains and different individual factors appear to be important depending on the ageing category. Further longitudinal studies and meta-analyses, segregating elderly by ageing rate, are warranted to clearly distinguish which factors are true determinants of malnutrition and not simply the consequences of the condition.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ESPEN:

-

European society of Clinical nutrition and metabolism

- FFM:

-

Fat free mass

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- HGS:

-

Handgrip strength

- SR:

-

Self-rated

References

World Health Organisation. Global Health and ageing. Geneva: WHO Press; 2011.

United Nations (2015) World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. no. ESA/P/WP.241.

European Commission (2017) Population Structure and Ageing http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Population_structure_and_ageing#Past_and_future_population_ageing_trends_in_the_EU (accessed 14th Sept 2017).

European Commission. Population ageing in Europe: facts, implications and policies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2014.

Sullivan DH. The role of nutrition in increased morbidity and mortality. Clin Geriatr Med. 1995;11:661–74.

Vellas BJ, Hunt WC, Romero LJ, et al. Changes in nutritional status and patterns of morbidity among free-living elderly persons: a 10-year longitudinal study. Nutrition. 1997;13:515–9.

Brownie S. Why are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency? Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:110–8.

Donini LM, De Bernardini L, De Felice MR, et al. Effect of nutritional status on clinical outcome in a population of geriatric rehabilitation patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:132–8.

Soderstrom L, Rosenblad A, Adolfsson ET, et al. Nutritional status predicts preterm death in older people: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:354–9.

Artacho R, Lujano C, Sanchez-Vico AB, et al. Nutritional status in chronically-ill elderly patients. Is it related to quality of life? J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18:192–7.

Arvanitakis M, Beck A, Coppens P, et al. Nutrition in care homes and home care: how to implement adequate strategies (report of the Brussels forum (22-23 November 2007)). Clin Nutr. 2008;27:481–8.

Volkert D. Malnutrition in older adults - urgent need for action: a plea for improving the nutritional situation of older adults. Gerontology. 2013;59:328–33.

Elia M, Russell CA, Stratton RJ. Malnutrition in the UK: policies to address the problem. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:470–6.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1734–8.

Keller HH. Promoting food intake in older adults living in the community: a review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:991–1000.

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237:143–9.

Hamer M, Lavoie KL, Bacon SL. Taking up physical activity in later life and healthy ageing: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:239–43.

Gutiérrez M, Tomás JM, Calatayud P. Contributions of psychosocial factors and physical activity to successful aging. Span J Psychol. 2018;21:E26.

Reichstadt J, Depp CA, Palinkas LA, et al. Building blocks of successful aging: a focus group study of older adults' perceived contributors to successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:194–201.

Volkert D, Saeglitz C, Gueldenzoph H, et al. Undiagnosed malnutrition and nutrition-related problems in geriatric patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:387–92.

Craven DL, Lovell GP, Pelly FE, et al. Community-living older Adults' perceptions of body weight, signs of malnutrition and sources of information: a descriptive analysis of survey data. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:393–9.

Craven DL, Pelly FE, Isenring E, et al. Barriers and enablers to malnutrition screening of community-living older adults: a content analysis of survey data by Australian dietitians. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23:196–201.

Pezzana A, Cereda E, Avagnina P, et al. Nutritional care needs in elderly residents of long-term care institutions: potential implications for policies. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:947–54.

Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN consensus statement. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:335–40.

Sobotka L, editor. Basics in clinical nutrition. 4th ed. Somerville, New Jersey: Galen; 2012.

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia M, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):1–9.

Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Correia M, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43(1):32–40.

Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (IRSPEN) (2015) Malnutrition in Ireland. http://www.irspen.ie/malnutrition/understanding-malnutrition/ (accessed 17th July 2017).

Ulger Z, Halil M, Kalan I, et al. Comprehensive assessment of malnutrition risk and related factors in a large group of community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:507–11.

Tasci I, Safer U, Naharci MI. Multiple Antihyperglycemic drug use is associated with Undernutrition among older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:1005–18.

Farre TB, Formiga F, Ferrer A, et al. Risk of being undernourished in a cohort of community-dwelling 85-year-olds: the Octabaix study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:702–9.

van der Pols-Vijlbrief R, Wijnhoven HA, Schaap LA, et al. Determinants of protein-energy malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;18:112–31.

Grammatikopoulou MG, Gkiouras K, Theodoridis X, et al. Food insecurity increases the risk of malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults. Maturitas. 2019;119:8–13.

Gunduz E, Eskin F, Gunduz M, et al. Malnutrition in community-dwelling elderly in Turkey: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:2750–6.

Ramage-Morin PL, Garriguet D. Nutritional risk among older Canadians. Health Rep. 2013;24:3–13.

Torres MJ, Dorigny B, Kuhn M, et al. Nutritional status in community-dwelling elderly in France in urban and rural areas. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105137.

Fjell A, Cronfalk BS, Carstens N, et al. Risk assessment during preventive home visits among older people. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:609–20.

Chen CC, Chang CK, Chyun DA, et al. Dynamics of nutritional health in a community sample of american elders: a multidimensional approach using Roy adaptation model. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2005;28:376–89.

de Morais C, Oliveira B, Afonso C, et al. Nutritional risk of European elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:1215–9.

Keller HH. Meal programs improve nutritional risk: a longitudinal analysis of community-living seniors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1042–8.

Serra-Prat M, Palomera M, Gomez C, et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia as a risk factor for malnutrition and lower respiratory tract infection in independently living older persons: a population-based prospective study. Age Ageing. 2012;41:376–81.

Simsek H, Meseri R, Sahin S, et al. Prevalence of food insecurity and malnutrition, factors related to malnutrition in the elderly: a community-based, cross-sectional study from Turkey. Eur Geriatr Med. 2013;4:226–30.

Fagerstrom C, Palmqvist R, Carlsson J, et al. Malnutrition and cognitive impairment among people 60 years of age and above living in regular housing and in special housing in Sweden: a population-based cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:863–71.

Geurden B, Franck ME, Lopez Hartmann M, et al. Prevalence of 'being at risk of malnutrition' and associated factors in adult patients receiving nursing care at home in Belgium. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:635–44.

Wham CA, McLean C, Teh R, et al. The BRIGHT trial: what are the factors associated with nutrition risk? J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18:692–7.

Pols-Vijlbrief R, Wijnhoven HA, Molenaar H, et al. Factors associated with (risk of) undernutrition in community-dwelling older adults receiving home care: a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:2278–89.

Ganhao-Arranhado S, Paul C, Ramalho R, et al. Food insecurity, weight and nutritional status among older adults attending senior centres in Lisbon. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:81–8.

Wham CA, Teh R, Moyes S, et al. Health and social factors associated with nutrition risk: results from life and living in advanced age: a cohort study in New Zealand (LiLACS NZ). J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:637–45.

van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Lonterman-Monasch S, de Vries OJ, et al. Prevalence and determinants for malnutrition in geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:1007–11.

Akin S, Şafak ED, Coban SA, et al. Nutritional status and related risk factors which may lead to functional decline in community-dwelling Turkish elderly. Eur Geriatr Med. 2014;5:294–7.

Tomstad ST, Soderhamn U, Espnes GA, et al. Living alone, receiving help, helplessness, and inactivity are strongly related to risk of undernutrition among older home-dwelling people. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:231–40.

Schone BS, Weinick RM. Health-related behaviors and the benefits of marriage for elderly persons. Gerontologist. 1998;38:618–27.

Krzyminska-Siemaszko R, Chudek J, Suwalska A, et al. Health status correlates of malnutrition in the polish elderly population - results of the Polsenior study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:4565–73.

Maseda A, Gomez-Caamano S, Lorenzo-Lopez L, et al. Health determinants of nutritional status in community-dwelling older population: the VERISAUDE study. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:2220–8.

Syrjala AM, Pussinen PI, Komulainen K, et al. Salivary flow rate and risk of malnutrition - a study among dentate, community-dwelling older people. Gerodontology. 2013;30:270–5.

Söderhamn U, Dale B, Sundsli K, et al. Nutritional screening of older home-dwelling Norwegians: a comparison between two instruments. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:383–91.

Romero-Ortuno R, Casey AM, Cunningham CU, et al. Psychosocial and functional correlates of nutrition among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:527–31.

Andrew MK, Mitnitski A, Kirkland SA, et al. The impact of social vulnerability on the survival of the fittest older adults. Age Ageing. 2012;41:161–5.

Cramer JT, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, et al. Impacts of high-protein Oral nutritional supplements among malnourished men and women with sarcopenia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:1044–55.

Smoliner C, Fischedick A, Sieber CC, et al. Olfactory function and malnutrition in geriatric patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1582–8.

Nykanen I, Lonnroos E, Kautiainen H, et al. Nutritional screening in a population-based cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23:405–9.

Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Weiss CO, et al. Financial strain is associated with malnutrition risk in community-dwelling older women. Epidemiol Res Int. 2012;2012:696518.

Chatindiara I, Williams V, Sycamore E, et al. Associations between nutrition risk status, body composition and physical performance among community-dwelling older adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43:56–62.

McElnay C, Marshall B, O'Sullivan J, et al. Nutritional risk amongst community-living Maori and non-Maori older people in Hawke's bay. J Prim Health Care. 2012;4:299–305.

Wham C, Maxted E, Teh R, et al. Factors associated with nutrition risk in older Maori: a cross sectional study. N Z Med J. 2015;128:45–54.

Jyrkka J, Mursu J, Enlund H, et al. Polypharmacy and nutritional status in elderly people. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:1–6.

Soderhamn U, Christensson L, Idvall E, et al. Factors associated with nutritional risk in 75-year-old community living people. Int J Older People Nursing. 2012;7:3–10.

Timpini A, Facchi E, Cossi S, et al. Self-reported socio-economic status, social, physical and leisure activities and risk for malnutrition in late life: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:233–8.

Zeanandin G, Molato O, Le Duff F, et al. Impact of restrictive diets on the risk of undernutrition in a free-living elderly population. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:69–73.

Martin CT, Kayser-Jones J, Stotts NA, et al. Risk for low weight in community-dwelling, older adults. Clin Nurse Spec. 2007;21:203–11 quiz 212-203.

Jung SE, Bishop AJ, Kim M, et al. Nutritional status of rural older adults is linked to physical and emotional health. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:851–8.

Crichton M, Craven D, Mackay H, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition: associations with geographical region and sex. Age Ageing. 2019;48:38–48.

Streicher M, van Zwienen-Pot J, Bardon L, et al. Determinants of incident malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults: a MaNuEL multicohort Meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(12):2335–43.

Kvamme JM, Gronli O, Florholmen J, et al. Risk of malnutrition is associated with mental health symptoms in community living elderly men and women: the Tromso study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:112.

Johnson CS. Psychosocial correlates of nutritional risk in older adults. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2005;66:95–7.

Krzyminska-Siemaszko R, Mossakowska M, Skalska A, et al. Social and economic correlates of malnutrition in polish elderly population: the results of PolSenior study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:397–402.

Lahmann NA, Tannen A, Suhr R. Underweight and malnutrition in home care: a multicenter study. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1140–6.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, et al. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:514–22.

Gil-Montoya JA, Subira C, Ramon JM, et al. Oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68:88–93.

Toussaint N, de Roon M, van Campen JP, et al. Loss of olfactory function and nutritional status in vital older adults and geriatric patients. Chem Senses. 2015;40:197–203.

Margetts BM, Thompson RL, Elia M, et al. Prevalence of risk of undernutrition is associated with poor health status in older people in the UK. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:69–74.

World Health Organisation WHO. Life Expectancy: Global Health Observatory (GHO) data; 2015. http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/. (accessed 12th Mar 2017)

Sharkey JR, Schoenberg NE. Variations in nutritional risk among black and white women who receive home-delivered meals. J Women Aging. 2002;14:99–119.

Weatherspoon LJ, Worthen HD, Handu D. Nutrition risk and associated factors in congregate meal participants in northern Florida: role of elder care services (ECS). J Nutr Elder. 2004;24:37–54.

Bardon LA, Streicher M, Corish CA, et al. Predictors of incident malnutrition in older Irish adults from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA) cohort- a MaNuEL study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018.

Shatenstein B, Kergoat MJ, Nadon S. Weight change, nutritional risk and its determinants among cognitively intact and demented elderly Canadians. Can J Public Health. 2001;92:143–9.

Schilp J, Wijnhoven HAH, Deeg DJH, et al. Early determinants for the development of undernutrition in an older general population: longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:708–17.

Roberts KC, Wolfson C, Payette H. Predictors of nutritional risk in community-dwelling seniors. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:331–6.

Fávaro-Moreira NC, Krausch-Hofmann S, Matthys C, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:507–22.

Cederholm T, Jagren C, Hellstrom K. Nutritional status and performance capacity in internal medical patients. Clin Nutr. 1993;12:8–14.

Abellan van Kan G, Rolland YM, Morley JE, et al. Frailty: toward a clinical definition. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:71–2 United States.

Pearson JM, Schlettwein-Gsell D, Brzozowska A, et al. Life style characteristics associated with nutritional risk in elderly subjects aged 80-85 years. J Nutr Health Aging. 2001;5:278–83.

Bakker MH, Vissink A, Spoorenberg SLW, et al. Are Edentulousness, Oral health problems and poor health-related quality of life associated with malnutrition in community-dwelling elderly (aged 75 years and over)? A cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1965.

Johansson L, Sidenvall B, Malmberg B, et al. Who will become malnourished? A prospective study of factors associated with malnutrition in older persons living at home. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:855–61.

Sharkey JR. Variation in nutritional risk among Mexican American and non-Mexican American homebound elders who receive home-delivered meals. J Nutr Elder. 2004;23:1–19.

Visvanathan R, Macintosh C, Callary M, et al. The nutritional status of 250 older Australian recipients of domiciliary care services and its association with outcomes at 12 months. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1007–11.

Sorbye LW, Schroll M, Finne Soveri H, et al. Unintended weight loss in the elderly living at home: the aged in home care project (AdHOC). J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:10–6.

Walls AW, Steele JG. The relationship between oral health and nutrition in older people. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:853–7.

Locher JL, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, et al. Social isolation, support, and capital and nutritional risk in an older sample: ethnic and gender differences. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:747–61.

Maseda A, Diego-Diez C, Lorenzo-López L, et al. Quality of life, functional impairment and social factors as determinants of nutritional status in older adults: the VERISAÚDE study. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:993–9.

Hernández-Galiot A, Goñi I. Quality of life and risk of malnutrition in a home-dwelling population over 75 years old. Nutrition. 2017;35:81–6.

Rullier L, Lagarde A, Bouisson J, et al. Psychosocial correlates of nutritional status of family caregivers of persons with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:105–13.

Haitz N. Old-age poverty in OECD countries and the issue of gender pension gaps; 2015.

Zunzunegui MV, Minicuci N, Blumstein T, et al. Gender differences in depressive symptoms among older adults: a cross-national comparison: the CLESA project. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:198–207.

Carayanni V, Stylianopoulou C, Koulierakis G, et al. Sex differences in depression among older adults: are older women more vulnerable than men in social risk factors? The case of open care centers for older people in Greece. Eur J Ageing. 2012;9:177–86.

Johansson Y, Bachrach-Lindstrom M, Carstensen J, et al. Malnutrition in a home-living older population: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. A prospective study. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1354–64.

Bailly N, Maitre I, Van Wymelbeke V. Relationships between nutritional status, depression and pleasure of eating in aging men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61:330–6.

Moriguti JC, Moriguti EK, Ferriolli E, et al. Involuntary weight loss in elderly individuals: assessment and treatment. Sao Paulo Med J. 2001;119:72–7.

Volkert D, Frauenrath C, Kruse W, et al. Malnutrition in old age--results of the Bethany nutrition study. Ther Umsch. 1991;48:312–5.

O'Keeffe M, Kelly M, O'Herlihy E, et al. Potentially modifiable determinants of malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2018.

Ritchie CS, Joshipura K, Silliman RA, et al. Oral health problems and significant weight loss among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M366–71.

World Health Organisation WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Luxembourg: WHO Press; 2014.

Hengeveld LM, Wijnhoven HAH, Olthof MR, et al. Prospective associations of poor diet quality with long-term incidence of protein-energy malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults: the health, aging, and body composition (health ABC) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:155–64.

Wolfe WS, Frongillo EA, Valois P. Understanding the experience of food insecurity by elders suggests ways to improve its measurement. J Nutr. 2003;133:2762–9.

Mignardot JB, Beauchet O, Annweiler C, et al. Postural sway, falls, and cognitive status: a cross-sectional study among older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:431–9.

Koren-Hakim T, Weiss A, Hershkovitz A, et al. The relationship between nutritional status of hip fracture operated elderly patients and their functioning, comorbidity and outcome. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:917–21.

Allard JP, Keller H, Jeejeebhoy KN, et al. Decline in nutritional status is associated with prolonged length of stay in hospitalized patients admitted for 7 days or more: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:144–52.

Suominen M, Muurinen S, Routasalo P, et al. Malnutrition and associated factors among aged residents in all nursing homes in Helsinki. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:578–83.

Galesi LF, Leandro-Merhi VA, de Oliveira MR. Association between indicators of dementia and nutritional status in institutionalised older people. Int J Older People Nursing. 2013;8:236–43.

Argiles JM. Cancer-associated malnutrition. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9(Suppl 2):S39–50.

Westergren A, Hagell P, Sjodahl Hammarlund C. Malnutrition and risk of falling among elderly without home-help service--a cross sectional study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18:905–11.

Wham C, Carr R, Heller F. Country of origin predicts nutrition risk among community living older people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:253–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was part-funded by the Irish Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine (DAFM) and the Irish Health Research Board (HRB). The funders had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LAB, CAC, MC, LCP, ERG and PDC were responsible for the review protocol and study hypothesis. LAB, ML, KLV, MGB and PDC were involved in conducting the literature search, screening potentially eligible studies, extracting and analysing studies. LAB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CAC, MC, LCP, ERG and PDC provided feedback on the first and subsequent drafts. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bardon, L.A., Corish, C.A., Lane, M. et al. Ageing rate of older adults affects the factors associated with, and the determinants of malnutrition in the community: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Geriatr 21, 676 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02583-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02583-2