Abstract

Introduction

Undernutrition is prevalent in older age. Current management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) requires modified diet patterns; however, older adults with diabetes may also be at the risk of undernutrition due to age, disease, and medication-related factors. Our objectives in this study were to examine the proportion and associations of undernutrition among community-dwelling older adults with T2DM.

Methods

This prospective, cross-sectional study involved older outpatient adults (≥ 65 years) with and without T2DM. We assessed the nutritional status using the Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form. Undernutrition referred to being either at risk of malnutrition or malnourished. Variables independently associated with undernutrition were evaluated by logistic regression analysis.

Results

Five hundred forty-six older adults [n = 215 with T2DM and n = 331 control; mean (SD) age, 74.9 (6.3) years; 388 (71.1%) female] were included in the study. The frequency of undernutrition was 31.1%, which was higher in patients with T2DM than in those without (36.7% vs. 27.5%, p < 0.05). However, the difference was no longer significant after adjustment for covariates (gender, lower education, lower body mass index, cardiovascular disease, multimorbidity, cognitive performance, functional performance, depressive symptoms, and polypharmacy). In the T2DM group, the ratio of multiple antihyperglycemic drug use (≥ 2) was higher in those with undernutrition compared with normal nutritional status (78.5% vs. 59.6%, p = 0.005). On multivariable analysis, decreased functional performance, depressive symptoms, and use of multiple antihyperglycemic drugs were associated with undernutrition in patients with T2DM.

Conclusions

Undernutrition was more common among older adults with T2DM compared with the control group. Undernutrition was further dependent on chronic conditions and diabetes management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term “malnutrition” is frequently used synonymously with “undernutrition” in the elderly [1]. Like many chronic conditions, undernutrition is prevalent among older adults and affects > 50% of nursing home residents [2, 3]. According to the latest International Diabetes Federation report (2017), the worldwide prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) among older adults (aged ≥ 65 years) is 18.8% and can be as high as 26.3% in North America [4]. Although one of the management strategies of type 2 DM (T2DM) is dietary modification as part of lifestyle changes [5,6,7], undernutrition may also occur in an older adult despite the diagnosis of T2DM. Indeed, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors are frequent among adults with DM aged ≥ 50 years [8]. In addition to multiple comorbidities and medications, these patients may have appetite changes, mobility limitations, social isolation, and economic difficulties, which contribute to poor nutritional status [9, 10]. Moreover, the consequences of undernutrition may be more troublesome in older adults with DM as they are prone to faster functional and cognitive decline [11,12,13]. These patients also have more comorbidities and complications compared with individuals without DM [14]. A recent study reported 69% higher mortality rates among patients with diabetes having undernutrition compared with those with normal nutritional status [15].

The prevalence of undernutrition may vary across populations from developed to less developed countries [6] or different settings of healthcare provision [2]. More than 50% of hospitalized older adults with DM may be at the risk of malnutrition [16, 17]. However, the rate and associations of undernutrition among community-dwelling older adults with T2DM are mostly unknown. Thus, our objectives in the present study were to investigate the frequency of undernutrition among older outpatients with T2DM compared with subjects without DM and to identify the relationships between the risk of undernutrition and other factors such as age, comorbidities, and medications.

Methods

Study Population

We recruited community-dwelling individuals who were ≥ 65 years old through the geriatrics outpatient clinic as part of a cross-sectional survey on the associations between cardiovascular disease and common geriatric comorbidities. The study sample included subjects with a history of physician-diagnosed T2DM. Individuals who had a history of T2DM but no active treatment were also included when their glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) value was > 7%. The control group included individuals who met the following criteria; no history of DM or hypoglycemic medications, no symptom of hyperglycemia, and normal fasting plasma glucose (< 100 mg/dl) and HbA1c (< 6.5%) levels. Subjects with dementia or cognitive deficits, delirium, or overt neuropsychiatric behavior, recent major surgery, limited mobility, or significant mobility impairment were excluded. The Institutional Review Board of Gulhane School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey, approved the study; written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the study procedures conform to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Working Protocol

Baseline characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1. Presence of coronary heart disease (CHD) was based on self-reported history of coronary revascularization, angiographic evidence of significant CHD, or a documented clinical history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris. Stroke diagnosis was based on self-reported history of a thrombotic event, cerebral hemorrhage, or small stroke/transient ischemic attack documented by hospital admission records. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) was diagnosed by the ankle-brachial index measurement [18]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) referred to the composite of CHD, stroke, and PAD. Due to lower LDL cholesterol goals, patients with T2DM were using more statins, and their mean LDL cholesterol level was lower than those without DM. Although a lower cholesterol level may be associated with malnutrition among the elderly [19], a recent study reported that statins also influence eating behavior in the long term [20]. Thus, the main dyslipidemia variable in our analyses was statin use. The definition of multimorbidity was consistent with ≥ 3 coexisting chronic conditions severe enough to require medications or lifestyle management [5, 21]. All participants had their weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) measured during the physical examination. Blood tests obtained during the outpatient geriatric evaluation were recorded for this research.

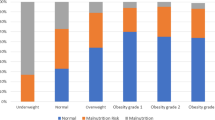

We evaluated the nutritional status using the Mini Nutritional Assessment short form (MNA-SF) [22]. The sum of questions on the MNA-SF can provide a maximum score of 14; a score ≥ 12 indicates normal nutritional status, a score between 8 and 11 indicates “at risk for malnutrition,” and a 0–7 score is indicative of “malnourishment.” Instead of the term “malnutrition,” “undernutrition” is used synonymously in the present report, which covers subjects who are classified as either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition by the MNA-SF [1].

We determined functional performance through the Barthel Index [23], which rates basic activities of daily living (BADL), and the Lawton-Brody instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale [24]. To assess cognitive functions, we used the Mini-Mental State Examination test (scores 0–30; higher scores show better cognitive functions) [25]. We evaluated depressive symptoms by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [26] (scores 0–15; scores > 5 show depression). Dementia was excluded using previously established criteria [27, 28].

Over- and undertreatment of DM was defined according to the health status-based HbA1c goals as recommended by the American Geriatrics Society (7.0–7.5%, 7.5–8.0%, and 8–9%) [29]. We defined the patients over- or undertreated when their HbA1c value remained below or above the recommended lower or upper limit for the corresponding health status category [5, 29]. Multiple antihyperglycemic drug use referred to the prescription of ≥ 2 antihyperglycemics (oral agents or oral agents plus insulin), and an insulin-based treatment indicated the use of insulin alone or insulin plus oral antihyperglycemics.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation). Categorical data were described as an absolute number and a percentage of the total or either group. Nonnormal distribution was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between patients with and without diabetes were analyzed using the independent t test, χ2 test, or Mann-Whitney U test. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to test linear correlations, and partial correlations were calculated by controlling for covariates. Uni- and multivariate logistic regressions were studied to identify independent variables associated with undernutrition. Associations at p ≤ 0.25 in univariate analysis were entered in the full model. The Box-Tidwell test was used to check the linearity of the logit for the continuous independent variables in logistic regression analysis. No significant violations of the linearity in the logit assumption were observed in the two final models. Multicollinearity was studied in each model. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS (PASW) 23.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient Description

The total sample included 546 participants (mean age: 74.9 ± 6.3 years, female: 71.1%). T2DM (n = 215) and control (n = 331) groups were matched for age and gender. As shown in Table 1, hypertension, statin use, CHD, PAD, CVD, anemia, and multimorbidity were more prevalent in patients with T2DM. These patients also had lower scores on MMSE, BADLs, and IADLs and higher scores on GDS compared with controls. Medication count and polypharmacy were also significantly higher in the T2DM group. There was a marginally significant difference in mean BMI between the patients and controls, but the proportion of individuals with BMI < 25 was similar.

Frequency of Undernutrition in the Total Sample

Mean MNA-SF score was significantly lower in patients with T2DM (Table 1). The proportion of subjects having undernutrition according to the MNA-SF score was 31.1% in the total sample. Most of the participants (90%) having undernutrition fell under the “at-risk” category. As shown in Table 1, patients with T2DM had a significantly higher prevalence of undernutrition compared with the controls. However, this difference was evident only in the “at-risk” category. The proportion of malnourished individuals was overall small in the two groups. There was no age-adjusted correlation between the MNA score and HbA1c in patients with T2DM (r = − 0.060, p = 0.423).

Undernutrition and Normal Nutritional Status in Patients with T2DM

T2DM patients having undernutrition (n = 79) and normal nutritional status (n = 136) were similar for most parameters. However, those having undernutrition were more often female and had more CHD, PAD, composite CVD, anemia, and multimorbidity (Table 2). Compared with those with normal nutritional status, the mean BMI was slightly higher in patients with undernutrition, but the prevalence of BMI < 25 was similar. Patients with undernutrition also had lower scores on MNA-SF, MMSE, BADL, and IADL tests and higher scores on GDS. Interestingly, their fasting plasma glucose was higher than in those with normal nutritional status. There were age-adjusted partial correlations between the MMSE and MNA-SF scores in both the total sample (r = 0.306, p < 0.001) and T2DM group (r = 0.332, p < 0.001).

There were numeric but nonsignificant differences between the patients with T2DM with and without undernutrition in the length of diabetes diagnosis, HbA1c, and the rates of over- and undertreatment. More patients with undernutrition were using multiple antihyperglycemic agents (≥ 2) compared with those with normal nutritional status (Table 2). There was no patient with normal nutritional status taking triple antihyperglycemics (≥ 3 oral agents or insulin), but 8.9% of the patients with undernutrition were on such treatment. Use of insulin-based treatments (single insulin or insulin plus oral antihyperglycemics) was similar in patients with and without undernutrition. The length of diabetes duration (mean approximately 10 years) correlated positively with the number of antihyperglycemic drugs (r = 0.338, p < 0.001).

Multiple Antihyperglycemic Use and its Association with Undernutrition

Uni- and multivariate associations of undernutrition with the study variables were tested in the total sample (Table 3). Logistic regression analysis showed that a lower BMI, lower scores on the Barthel Index, lower scores on MMSE, and presence of depressive symptoms were independently associated with undernutrition in the total sample.

In patients with T2DM, univariate associations were significant between undernutrition and female gender, lower education, CVD, lower scores on MMSE and BADL tests, and depressive symptoms (Table 4). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjustment for covariates, lower scores on the Barthel Index, depressive symptoms, and the use of multiple antihyperglycemic drugs were independently associated with undernutrition. Unlike the total sample, BMI < 25 was not associated with undernutrition in patients with T2DM. Also, there were no independent associations between undernutrition and insulin use, diabetes overtreatment or diabetes undertreatment in patients with T2DM.

Discussion

In this study of community-dwelling older adults, we found that a diagnosis of T2DM was associated with increased prevalence of undernutrition compared with matched controls without DM. However, after controlling for confounders, T2DM was not independently associated with undernutrition, but the presence of a lower BMI, poor cognition, reduced functional performance, depressive symptoms, and taking multiple antihyperglycemic drugs determined the increased risk in these patients. Our findings also indicated that there were more comorbidities, mostly age related, in patients with T2DM having undernutrition whose glycometabolic state was also unhealthy (i.e., higher HbA1c, higher FPG, BMI around 30, more drug use, more undertreatment) (Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report this kind of a relationship between T2DM, undernutrition, disease-specific medications, and geriatric conditions. The study indicates that, in the presence of some age- and disease-related factors, older adults with T2DM may suffer from undernutrition more than their counterparts without DM.

We used the MNA-SF to define nutritional status [30] because of ease of application and usefulness in both clinical practice and research settings [31, 32]. Because the MNA includes functional, psychologic, and cognitive parameters, it was proposed to be a more appropriate tool for geriatric individuals to assess malnutrition [33]. Moreover, a lower MNA score can predict functional dependence, suggesting a further role for its clinical usefulness in the care of older adults [34].

The frequency of undernutrition may be higher in hospitalized patients with DM, especially in individuals having multiple comorbidities [35]. However, less is known about community-dwelling older adults. An earlier study with 35 older adults with T2DM and 35 matched control subjects evaluated the frequency of undernutrition by the MNA full form in a case-control design [36]. The patient group scored worse on the MNA, and most of them were in the at-risk category. There were also simple correlations between the scores on the MNA and ADLs tests, but the authors were not able to assess potential associates of poor nutrition because of the small sample size. Our findings are mainly in agreement with these findings, but we also found that a lower score on the Barthel Index was independently associated with undernutrition in both the diabetes group and the overall sample.

Although patients with DM may need to use more drugs [37], there were no associations between polypharmacy and undernutrition in this study. Among older adults, even polypharmacy (when defined as taking ≥ 10 drugs) was not consistently associated with malnutrition in either gender in a previous meta-analysis [38]. However, in the present study, the use of two or more antihyperglycemic drugs was recorded twice more in patients with T2DM having undernutrition, and this variable was independently associated with undernutrition. Moreover, the length of diabetes duration correlated positively with the number of antihyperglycemic drugs. This finding is in agreement with an earlier study that showed that most patients needed more than one antihyperglycemic drug at 9 years [39]. While the requirement of more drugs to treat DM may indicate a more complicated disease, insulin-based treatments, another marker of disease severity, did not significantly modulate undernutrition in our study. Similarly, over- or undertreatment showed no influence on nutritional status.

Previous studies have raised concerns about the safety of antihyperglycemic combination therapies in relation to diabetes-related outcomes such as hypoglycemia [40], cardiovascular events and mortality [41], and microvascular complications [42]. However, recent studies have also focused on some less-known safety issues related to multiple drug use, including dementia [43], fracture risk [44], and community-acquired pneumonia [45]. Our findings suggest that undernutrition is another condition that can be found more frequently in older adults with T2DM requiring multiple antihyperglycemics.

Compared with people without DM, BADL and IADL limitations are generally more common in patients with DM [46]. Association of nutrition with BADL capability in our study was previously reported in institutionalized older adults [47]. At present, BADL dependency seems to be a significant risk for undernutrition in subjects with or without DM. Unlike BADLs, we observed no association of the scores on IADLs test with the nutritional status in either the total sample or the T2DM group. However, in a study conducted using a clinical database, IADL but not BADL dependency was a predictor of undernutrition among community-dwelling older adults [48]. Nevertheless, that study defined BADL or ADL dependency arbitrarily through patient interviews without referring to specific assessment tools. Because IADL includes more complex tasks compared with BADL, the amount of impairment was probably not severe enough to influence the nutritional status of our community-dwelling participants.

Depressive symptoms, a must-have confounder in clinical nutrition research, were consistently associated with undernutrition in the present study in both the overall sample and the T2DM group. Our results confirmed the well-known association of undernutrition and depression in the community setting [48]. Moreover, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey cohort also identified the symptoms of depression among the causative factors for weight loss even in the adults < 65 years of age [49]. Increased rates of undernutrition in patients with T2DM having depressive symptoms in our study emphasize the importance of regular screening of these individuals [5].

Undernutrition may adversely affect functional and cognitive performance in the long term [50]. Cognitive disorders are more common among older adults with DM [51], and these patients have increased odds of having dementia in later years [7, 37]. Although dementia is a well-known cause of nutritional disorders, the association of cognitive decline with undernutrition among older adults without dementia is less clear [52]. We did not enroll patients with dementia, but 69% of our sample had scores < 30 on the MMSE test, indicating not all of our participants had similar cognitive skills. A lower MMSE score was associated with increased likelihood of undernutrition in the whole sample but not in the T2DM group when separately analyzed. On the other hand, patients with T2DM having undernutrition scored significantly lower on the MMSE test than those with normal nutritional status. Furthermore, we observed correlations between the MMSE and MNA-SF scores in both the overall sample and the T2DM group. Thus, our findings suggest the need to explore the adverse effects of poorer cognition on nutritional status among community-dwelling older adults with T2DM.

We would like to point out the strengths of the study, which include the prospective design, extensive data set, collection of nutritional, functional, and cognition data using validated tools, and exclusion of dementia, which causes a particular type of eating disorder. Consequently, data consistency and quality are reflected in the findings of well-known measures in studies with the elderly. Our study also had several limitations, includeing the cross-sectional design, limiting conclusions regarding causality. Second, we were not able to test the association of microvascular complications of T2DM with the nutritional status, but their influences on functional performance cannot be neglected. Third, drug-food interactions and quality of life measures such as income, mobility, pain, oral, and social relationships, which are known to affect eating behavior [9, 10, 53], were also not available in this project. Lastly, the present study did not include food insecurity as a confounder, which is an important but less recognized predictor of undernutrition [54].

Conclusions

We found one-third of community-dwelling older adults with T2DM struggle with undernutrition, which was independently associated with some age- and disease-related factors including functional performance, depressive symptoms, and use of multiple antihyperglycemic drugs. While the prescription of antihyperglycemic drugs have been increasing [55] and there is limited evidence regarding deprescribing of hypoglycemic medicines [56], restricted food intake or poor choices may adversely affect the nutritional status among older adults with T2DM having functional limitations, psychologic disturbances, and multiple antihyperglycemic drug use.

References

White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M. Consensus statement: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. J Parenteral Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:275–83.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Rämsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1734–8.

Bell CL, Tamura BK, Masaki KH, Amella EJ. Prevalence and measures of nutritional compromise among nursing home patients: weight loss, low body mass index, malnutrition, and feeding dependency, a systematic review of the literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:94–100.

Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2650–64.

Dyson PA. A practical guide to delivering nutritional advice to people with diabetes. Diabetes Therapy. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-018-0556-4.

Kalra S, Sharma SK. Diabetes in the elderly. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:493–500.

Nelson KM, Reiber G, Boyko EJ, Nhanes III. Diet and exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes: findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III). Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1722–8.

Drewnowski A, Warren-Mears VA. Does aging change nutrition requirements? J Nutr Health Aging. 2001;5:70–4.

Brownie S. Why are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency? Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:110–8.

Gregg EW, Beckles GL, Williamson DF, et al. Diabetes and physical disability among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1272–7.

Volpato S, Blaum C, Resnick H, et al. Comorbidities and impairments explaining the association between diabetes and lower extremity disability: the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:678–83.

Gregg EW, Yaffe K, Cauley JA, et al. Is diabetes associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline among older women? Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:174–80.

American Diabetes Association. 12. Older adults: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2018;42:S139–47.

Ahmed N, Choe Y, Mustad VA, et al. Impact of malnutrition on survival and healthcare utilization in Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6:e000471.

Vischer UM, Perrenoud L, Genet C, Ardigo S, Registe-Rameau Y, Herrmann FR. The high prevalence of malnutrition in elderly diabetic patients: implications for anti-diabetic drug treatments. Diabetes Med. 2010;27:918–24.

Sanz Paris A, Garcia JM, Gomez-Candela C, Burgos R, Martin A, Matia P. Malnutrition prevalence in hospitalized elderly diabetic patients. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28:592–9.

Tasci I, Safer U, Naharci MI, et al. Undetected peripheral arterial disease among older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2018;33:5–11.

Casiglia E, Mazza A, Tikhonoff V, Scarpa R, Schiavon L, Pessina AC. Total cholesterol and mortality in the elderly. J Intern Med. 2003;254:353–62.

Sugiyama T, Tsugawa Y, Tseng C-H, Kobayashi Y, Shapiro MF. Different time trends of caloric and fat intake between statin users and nonusers among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1038.

Laiteerapong N, Iveniuk J, John PM, Laumann EO, Huang ES. Classification of older adults who have diabetes by comorbid conditions, United States, 2005–2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E100.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:782–8.

Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–9.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44.

Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Montes-Paixao Junior C, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of newly proposed clinical criteria for possible vascular dementia. Neurology. 1997;49:690–4.

Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2020–6.

Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–72.

Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, et al. Overview of the MNA–its history and challenges. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:456–63 (discussion 463–5).

Martín A, Ruiz E, Sanz A, et al. Accuracy of different mini nutritional assessment reduced forms to evaluate the nutritional status of elderly hospitalised diabetic patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;20:370–5.

Donini LM, Poggiogalle E, Molfino A, et al. Mini-nutritional assessment, malnutrition universal screening tool, and nutrition risk screening tool for the nutritional evaluation of older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(959):e11–8.

Schrader E, Baumgartel C, Gueldenzoph H, et al. Nutritional status according to mini nutritional assessment is related to functional status in geriatric patients—independent of health status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;18:257–63.

Corkins MR, Guenter P, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients: united States, 2010. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:186–95.

Turnbull PJ, Sinclair AJ. Evaluation of nutritional status and its relationship with functional status in older citizens with diabetes mellitus using the mini nutritional assessment (MNA) tool–a preliminary investigation. J Nutr Health Aging. 2002;6:185–9.

Bannister M, Berlanga J. Effective utilization of oral hypoglycemic agents to achieve individualized HbA1c targets in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7:387–99.

Fávaro-Moreira NC, Krausch-Hofmann S, Matthys C, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:507–22.

Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, Holman RR. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA. 1999;281:2005–12.

Downes MJ, Bettington EK, Gunton JE, Turkstra E. Triple therapy in type 2 diabetes; a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1461.

Kuo S, Yang C-T, Wu J-S, Ou H-T. Effects on clinical outcomes of intensifying triple oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) therapy by initiating insulin versus enhancing OAD therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide population-based, propensity-score-matched cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:312–20.

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Diabetes treatments and risk of amputation, blindness, severe kidney failure, hyperglycaemia, and hypoglycaemia: open cohort study in primary care. BMJ. 2016;352:i1450.

Bohlken J, Jacob L, Kostev K. Association between the use of antihyperglycemic drugs and dementia risk: a case-control study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;66:725–32.

Losada E, Soldevila B, Ali MS, et al. Real-world antidiabetic drug use and fracture risk in 12,277 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a nested case–control study. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:2079–86.

Gorricho J, Garjón J, Alonso A, et al. Use of oral antidiabetic agents and risk of community-acquired pneumonia: a nested case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:2034–44.

Wu JH, Haan MN, Liang J, Ghosh D, Gonzalez HM, Herman WH. Diabetes as a predictor of change in functional status among older Mexican Americans: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:314–9.

Cereda E, Valzolgher L, Pedrolli C. Mini nutritional assessment is a good predictor of functional status in institutionalised elderly at risk of malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:700–5.

van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Lonterman-Monasch S, de Vries OJ, Danner SA, Kramer MHH, Muller M. Prevalence and determinants for malnutrition in geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:1007–11.

DiPietro L, Anda RF, Williamson DF, Stunkard AJ. Depressive symptoms and weight change in a national cohort of adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16:745–53.

Formiga F, Ferrer A, Padrós G, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for functional and cognitive decline in very old people: the Octabaix study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:924–8.

Munshi MN. Cognitive dysfunction in older adults with diabetes: what a clinician needs to know. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:461–7.

Orsitto G. Different components of nutritional status in older inpatients with cognitive impairment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:468–71.

Hays NP, Roberts SB. The anorexia of aging in humans. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:257–66.

Burks CE, Jones CW, Braz VA, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition among older adults in the emergency department: a multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1741–7.

Naser AY, Wang Q, Wong LYL, et al. Hospital admissions due to dysglycaemia and prescriptions of antidiabetic medications in england and wales: an ecological study. Diabetes Therapy. 2017;9:153–63.

Black CD, Thompson W, Welch V, et al. Lack of evidence to guide deprescribing of antihyperglycemics: a systematic review. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:23–31.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Ilker Tasci and Umut Safer designed the study and developed the methodology; Ilker Tasci, Umut Safer and Mehmet Ilkin Naharci collected the data; Ilker Tasci and Mehmet Ilkin Naharci performed the analysis; Ilker Tasci wrote the manuscript; Ilker Tasci, Umut Safer and Mehmet Ilkin Naharci drafted and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

All three authors (Ilker Tasci, Umut Safer and Mehmet Ilkin Naharci) have no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The Institutional Review Board of Gulhane School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey, approved the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were also in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Gulhane School Medicine, Ankara, Turkey) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7837703.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tasci, I., Safer, U. & Naharci, M.I. Multiple Antihyperglycemic Drug Use is Associated with Undernutrition Among Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Ther 10, 1005–1018 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0602-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0602-x