Abstract

Background

Dementia in the oldest-old is projected to increase exponentially as is the burden of their caregivers who may experience unique challenges and suffering. Thus, we aim to investigate which factors are associated with older caregivers’ burden in caring demented outpatients in a multicenter cohort.

Methods

Patients and their caregivers, both aged ≧65 years, in the National Dementia Registry Study in Taiwan (T-NDRS) were included in this study. Caregiver burden was measured with the short version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI). The correlations between the ZBI scores and characteristics of caregivers and patients, including severity of dementia, physical comorbidities, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), neuropsychiatric symptoms assessed by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), and family monthly income, were analyzed.

Results

We recruited 328 aged informal caregiver-patient dyads. The mean age of caregivers was 73.7 ± 7.0 years, with female predominance (66.8%), and the mean age of patients was 78.8 ± 6.9 years, with male predominance (61.0%). Multivariable linear regression showed that IADLs (β = 0.83, p < 0.001) and NPI subscores of apathy (β = 3.83, p < 0.001)and irritability (β = 4.25, p < 0.001) were positively associated with ZBI scores. The highest family monthly income (β = − 10.92, p = 0.001) and caregiver age (β = − 0.41, p = 0.001) were negatively correlated with ZBI scores.

Conclusions

Older caregivers of older demented patients experience a higher care burden when patients had greater impaired functional autonomy and the presence of NPI symptoms of apathy and irritability. Our findings provide the direction to identify risky older caregivers, and we should pay more attention to and provide support for these exhausted caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dementia is characterized by irreversible and progressive impairments in cognition, behavioral function and activities of daily living (ADL). The growing numbers of people affected by dementia, with the number expected to double every 20 years worldwide, makes caring in dementia a global public health issue [1]. Because the symptoms of dementia interfere with patient function and increase their dependency, patients with dementia require more support in daily living and long-term care from their caregivers, which often results in substantial financial and health distress of their caregivers [2]. The obligation to care for dementia patients is often shifted to their original family, mainly the spouse, children or siblings of the patients. Many of them have to cut back on work to take the role as caregivers and face additional expensive medical services. Dementia patient caregivers encounter extra household expenditure, which has been shown to be associated with their caring role [3]. As family is expected to be the primary source of care going forward, especially in Asian populations, understanding the burden suffered by family caregivers of dementia patients is of great importance.

Dementia caregiving has negative associations with the caregiver’s physical and mental illness [4,5,6]. Previous research has found that various factors, such as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and abnormal behaviors of demented patients, more severe dementia severity, higher functional dependence, cognitive impairment, low level of education and family income, and impaired health status of the caregivers are significantly associated with higher caregiver burden [7, 8]. Although studies have tried to investigate the factors associated with caregiver burden, there is a lack of research focusing on older caregivers of patients with dementia. The age of most caregivers in past studies is often mixed, ranging from 50 to 65 years old [9,10,11,12].

Taiwan has entered the stage of an aged society as people over 65 years old accounted for more than 15.3% of the country’s total population [13], and this group includes a large number of demented patients and their caregivers. However, the increase in dementia in the older adults coincides with a dramatic decline in the potential support ratio, namely, the number of persons aged 20–64 per person aged 65 or older [12]. According to the population projections reported by the National Development Council of Taiwan, the potential support ratio is predicted to drop from 5.9 in 2015 to approximately 2.7 by 2030 [14], with similar declines expected in most countries worldwide [12, 15]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of older people who have become caregivers for their elderly relatives. There is a need to examine the social context in which an older individual must take care of a centenarian one with dementia, although this emerging problem has been overlooked, and few studies have emphasized this collateral issue.

The aim of this study was to investigate factors that may be associated with informal caregiver burden for those who provide “elderly-for-elderly care”. We examined the associations among caregiver burden and demographic variables of patients and caregivers, NPS, cognitive impairments, physical dependencies, underlying medical conditions, and contextual factors in a large multicenter cohort of aged caregiver-patient dyads.

Methods

The National Dementia Registry Study in Taiwan (T-NDRS) is a multicenter research study conducted by the Institute of Population Health Sciences, Taiwan National Health Research Institute since 2017. Eight hospitals (three in northern Taiwan, two in middle Taiwan and three in southern Taiwan) participated in this project. All patients with dementia received clinical examinations, including a thorough survey of medical history, physical and neurological evaluations, laboratory tests (complete blood counts, serum B12 and folic acid, thyroid hormone levels, syphilis serology, routine biochemical tests) and brain image evaluations (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). The T-NDRS aimed to investigate the baseline characteristics (including demographics, cognitive status, and other measures), cognitive and functional changes in patients with dementia and their caregivers’ burden. The T-NDRS study was approved by the ethics committees of the hospital sites.(National Health Research Institutes, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Changhua Christian Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Cardinal Tien Hospital) Written informed consent and permission for interviews were received from all study participants and their main adult caregivers.

Study overview and inclusion criteria

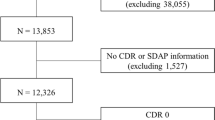

All participants received assessments, and their family caregivers reported patients’ NPS and their own caregiver burden. General demographics and clinical information, such as history of major psychiatric diseases, neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric disturbances, functional disability, ADLs, and monthly income, physical activity per week were collected [16]. For inclusion, patients in the age range between 65 and 90 years must had a diagnosis of dementia with a clinical dementia rating (CDR) score ≧0.5 (covering from very mild to severe dementia) and had at least one main caregiver defined as the person who frequently took care of/talked to/interacted with the dementia patient for at least 10 h a week. The caregivers should accompany the dementia patients for the interview and annual follow-ups. The exclusion criteria for all participants included having any other central nervous system disease other than dementia, having psychosis not due to dementia, having alcohol use disorder or hepatic encephalopathy, or having expected life expectancy less than 6 months. Only family caregiver-patient dyads aged ≧65 years old were analyzed in this study. From 2017 to 2019, 328 elderly patient-caregiver dyads (19.2%) were retrieved from the T-NDRS database (Fig. 1).

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of dementia type was made according to any of the following criteria: (1) NIA-AA criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [17], (2) NINDS-AIREN criteria for vascular dementia [18], (3) Lund-Manchester criteria of frontotemporal dementia [19], (4) 2015 International Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) conference criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies [20], and (5) The Movement Disorders Society (MDS) criteria for dementia from Parkinson’s disease [21].

Assessment of questionnaire and scores

Mini-mental status exam (MMSE)

The MMSE demonstrates moderately levels of reliability and is a most often used assessment instrument for dementia screening. It provides a total score ranging from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. It was administered to patients to provide an overall measure of cognitive impairment [22].

Clinical dementia rating scale (CDR)

The severity of dementia was defined according to the CDR [23]. The CDR is a widely used clinical staging instrument characterizing the manifestation and severity of dementia, that is generated from a semi-structured interview with the patient and a knowledgeable informant evaluating six areas of cognitive domains (memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). The overall CDR is derived by synthesizing ratings in each of the six domains where score = 0 indicates normal, score = 0.5 signifies uncertain or very mild impairment, and score = 1, 2, or 3 corresponds to mild, moderate, or severe impairment.

Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q)

The NPI-Q is a validated caregiver-based questionnaire in which the informants indicated the presence and severity of NPS and caregiver distress in the demented patient during the last few weeks [24]. The informant rates both the severity of the symptoms present on a 3-point scale (1 = mild; 2 = moderate; and 3 = severe) and the associated distress on them using a 5-point scale (0 = no distress; 1 = minimal distress; 2 = mild distress; 3 = moderate distress; 4 = severe distress; and 5 = extreme distress). A total score for the NPI-Q was generated by summing all the individual severity scores.

Instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADL)

The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale was used to evaluate independent living skills such as doing a laundry, telephone using, and dealing with financial matters of the persons with dementia, which consisted of 8 domains of functions [25]. Persons are scored according to their highest level of functioning in that category. A summary score ranges from 0 (low function, dependent) to 8 (high function, independent).

Zarit burden interview (ZBI)

The ZBI is a well-known self-report measure of perceived burden among caregivers. The instrument measures the caregiver’s emotion, psychological health, well-being, social and family life, finances, and degree of control over one’s life [26]. This version contains 22 items and each item on the questionnaire question is a statement which the caregiver is asked to endorse on a 5-point Likert scale (0: never; 1: rarely; 2: sometimes, 3: quite frequently; and 4: nearly always).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented by numbers with percentages, and continuous variables were presented by means with standard deviations. Chi-square tests and independent t-tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariable linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the associations between covariates and ZBI scores (caregiver burden). β values and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated after adjustments in different models. Multivariable linear regression model 1 was adjusted for all variables listed in Table 1 except NPI total scores and NPI severity scores for the 12 items. Model 2 and model 3weremodel 1 plus adjusting for the total summed NPI severity scores or the severity score for each NPI item, respectively. Finally, the approaches of stepwise selection were applied in model 2 and model 3 to identify significant covariables for caregiver burden. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0(IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) with 2-tailed statistical tests. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We did the power analysis for multiple regression and the power achieved is 99% with sample size of 328.

Results

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients and their caregivers are presented in Table 1. A total of 328 patients (61% male, mean age = 78.8, mean education = 9.5 years) were included. Their caregivers were mostly female (66.8%), with a mean age of 73.7 years and a mean education of 10.1 years. The mean ZBI score was 26.7 ± 18.1. The majority of caregivers were spouses (87.0%) or offspring (8.8%). Most caregivers lived with the patients (91.5%) and had earnings in the middle family income class. The caregivers had a similar age distribution to the patients with dementia, with the exception that the caregivers aged over 95 years mostly took care of patients aged 75–84 years (Table 1). Regarding the relationships between the patients and caregivers, the spouses (n = 285) were in dyads with patients aged 78.1 ± 6.7 years, and caregivers aged 74.6 ± 7.0 years; the offspring (n = 29) were in dyads with patients aged 88.0 ± 2.1 years, and caregivers aged 67.0 ± 1.6 years. With regard to the dementia severity of patients, the average scores were 17.8 on the MMSE, 1.2 on the CDR, and 4.3 on the IADL. Each NPI item demonstrated similar averaged severity with the exception of relatively lower severity of euphoria and relatively higher severity of sleep/nighttime behavior change.

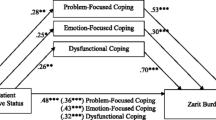

In multivariable model 1(Table 2), the ZBI scores were negatively associated with the highest income class but positively associated with IADLs. Physical diseases, psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder and anxiety, physical activities and life habits such as drinking and smoking did not show an influence on the ZBI scores. After the total NPI score was added to the analysis (model 2, Table 2), the NPI total scores were positively associated with increases in the ZBI scores (β: 1.09, 95% CI: 0.68 to 1.49, p < 0.001). We further analyzed each NPI item in model 3 (Table 2). The NPI scores for the apathy, depression and irritability domains were significantly associated with ZBI scores. For every additional unit of severity for the aforementioned NPI domains, there was a 3.7-point increase in the ZBI score for apathy (95% CI: 1.5 to 5.9, p = 0.001), a 3.3-point increase for irritability (95% CI: 0.3 to 6.3, p = 0.03) and a 3.0-point decrease for depression (95% CI:-6.0 to − 0.0, p = 0.047). In addition, the NPI anxiety and euphoria domains delivered trend-like positively related influences (Table 2).

In the stepwise multivariable regression (Table 3), the model that included total NPI severity scores showed that IADLs, the highest class of family income, caregiver age and total NPI severity scores were significantly correlated with the ZBI scores. In detail and listed by the order of importance, another model including the 12 NPI items demonstrated that IADLs, NPI_irritability/lability, NPI_apathy/indifference, the highest family income, and caregiver age had significant influences on the ZBI scores. Other NPI domains did not have a significant impact on caregiver burden.

Discussion

This nationwide multicenter study included informal caregivers of patients who, for the most part, suffered from mild or moderate probable or possible AD and exhibited, on average, mild NPS (Table 1). The study was performed in 8 memory clinics of medical centers and local hospitals in both urban and rural areas. Among our aged patient-caregiver dyads, most patients were male and cared for by female family caregivers. This corresponds to international findings that have shown that caregiving for dementia patients is usually informal and a female dominant [9, 27,28,29,30,31]. Spouses played a major role (86.9%) in caregiving in these old-old dyads, rather than offspring, such as middle-aged daughters or daughters-in-law [32, 33].

We found that family monthly income, IADL functional impairment, NPS, and caregiver age emerged as independent predictors of elderly caregiver burden in the present cohort regarding after adjusting for severity of dementia, medical comorbidities, education, relationship between patients and caregivers, and physical activities per week. Many studies have consistently found that both NPS and functional impairment caused more distress to family caregivers than other care demands, such as cognitive deficits [8].

Our findings corroborate previous research that IADL deficits in patients with dementia were associated with more caregiver burden and depression [34, 35].In addition to the physical burden of the caregivers, the ADL dependency of the patient is also correlated with the number of care hours, and it has been shown to be the only factor independently associated with missing more hours at work for those who were employed [29].

By conducting multiple regression analysis using different NPS as individual predictors of caregiver burden, we found that the NPI apathy and NPI irritability subscores were independent factors for caregiver burden. In a prior study of 548 French caregivers without mention of the mean value of caregivers’ age, it found that apathy, agitation/aggression, aberrant were related to caregivers’ burden significantly [34]. Other studies recruited older adult caregivers mainly showed that delusions, agitation/aggression and irritability of demented patients caused the most distress to their caregivers [10, 36]. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia may worsen the caregiver’s burden of providing care for ADLs [37]. Resistiveness to care is common in demented patients especially those residing at home, Fauth and colleagues found that NPS that observed in the context of ADL assistance (i.e., care refusal) mainly accounted for the relation between ADL dysfunction and level of caregiver burden [38].

Dementia creates a substantial burden on human and financial resources, and the costliest part of the total cost of home care is unpaid assistance [39]. It is common for family caregivers to experience financial strain as a result of providing care during the long disease course of dementia, both when the relative is cared for at home or in nursing homes [40]. Adult caregivers with low incomes perceive more distress than caregivers with higher incomes [11, 41], and low levels of financial resources have been shown to predict depressed mood in caregivers of persons with dementia [42]. Caregivers with higher financial resources probably have more access to supportive services (home health aides, adult day care) that may reduce their burden [42]. Compared with adult caregivers, most elderly caregivers are retired or unemployed. The government launched he Long-Term Care 2.0 (LTC2.0) Plan in 2016 and the payment system was categorized into four parts as personal care, professional care, transportation assistive devices and barrier free environment modification, and respite care for family caregivers. Each recipient has an upper limit and care delivery is paid by fee-for-service. Although co-payments are exempted for extremely-low-income users, others are responsible for fee for service usage exceeding the upper limit with the co-payment rate of 16% under current LTC2.0 system [43]. Developing policies such as programs that pay family caregivers, providing financial compensation, and special tax deductions for caregivers may be helpful. Further larger-scale follow-up cohort studies are required to verify this opinion.

Similar to several publications [27, 30, 44, 45] but in contrast to other studies [46,47,48], our study revealed an inverse relationship between caregiver burden and caregiver age among those aged 65 and older. Young-old caregivers may still be at work, and caregiving-related contradiction with their job and leisure activities might explain the more severe burden in young-old than old-old caregivers.

Our findings may help to identify elderly caregivers who are at risk of caregiver burden and serve to take targeted steps to alleviate their suffering, such as effective management of IADL functional decline and NPS of the client, personal and psychological support for the caregiver, and presumably, better financial funding of informal care.

This study had several limitations. First, information about caregiver-related comorbidities and general health conditions, social support, and cumulative duration of care was not available in the T-NDRS. Without these, we cannot evaluate their impacts. Family caregivers of person with dementia reported a greater number of physical health problems and worse overall health compared with non-caregiver controls [49]. Since we didn’t evaluate the underlying diseases of family caregivers (such as diabetes, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, poor immune functioning) which may contribute to caregiver burden, the present study could not go further to explore the influence between caregiver’s general health and burden. Second, this study only recruited family caregiver-patient dyads who had sought medical services. Although different types of caregivers may have different level of perceived burden, previous studies found that no matter whether the background of the caregiver is family, professional, or paid caregiver, the most relevant burden is psychological burden and stress caused by behavioral disturbances [50, 51]. In addition, most of the eight participating hospitals were medical centers, and our findings may not be generalizable to those visiting community clinics alone or those not seeking medical help.

Conclusion

Older caregivers of aged demented patients experience higher caregiver burden, which may be positively associated with impairments in functional autonomy and more severe NPS of apathy and irritability and negatively correlated with higher family income.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Dementia Registry Study group (T-NDRS) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of T-NDRS study group (National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan) via corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- CDR:

-

Clinical dementia rating

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale

- MDS:

-

Movement Disorders Society

- MMSE:

-

Mini-mental Status Exam

- NPI-Q:

-

Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire

- NPS:

-

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

- T-NDRS:

-

National Dementia Registry Study in Taiwan

- ZBI:

-

Zarit Burden Interview

References

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75 e2.

Prince M, Dementia Research G. Care arrangements for people with dementia in developing countries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(2):170–7.

Philp I, McKee KJ, Meldrum P, Ballinger BR, Gilhooly ML, Gordon DS, et al. Community care for demented and non-demented elderly people: a comparison study of financial burden, service use, and unmet needs in family supporters. BMJ. 1995;310(6993):1503–6.

von Kanel R, Mausbach BT, Patterson TL, Dimsdale JE, Aschbacher K, Mills PJ, et al. Increased Framingham coronary heart disease risk score in dementia caregivers relative to non-caregiving controls. Gerontology. 2008;54(3):131–7.

Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE, Semple SJ, Grant I. Accelerated risk of hypertensive blood pressure recordings among Alzheimer caregivers. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(3):215–27.

Joling KJ, van Marwijk HW, Veldhuijzen AE, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, Smit F, et al. The two-year incidence of depression and anxiety disorders in spousal caregivers of persons with dementia: who is at the greatest risk? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):293–303.

Bergvall N, Brinck P, Eek D, Gustavsson A, Wimo A, Winblad B, et al. Relative importance of patient disease indicators on informal care and caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(1):73–85.

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):112–28.

Bleijlevens MH, Stolt M, Stephan A, Zabalegui A, Saks K, Sutcliffe C, et al. Changes in caregiver burden and health-related quality of life of informal caregivers of older people with Dementia: evidence from the European RightTimePlaceCare prospective cohort study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(6):1378–91.

Huang SS, Lee MC, Liao YC, Wang WF, Lai TJ. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in Taiwanese elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(1):55–9.

Andren S, Elmstahl S. Relationships between income, subjective health and caregiver burden in caregivers of people with dementia in group living care: a cross-sectional community-based study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(3):435–46.

Win KK, Chong MS, Ali N, Chan M, Lim WS. Burden among Family Caregivers of Dementia in the Oldest-Old: An Exploratory Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017;4:205.

Interior Mot. Monthly Bulletin of Interior Statistics for the R.O.C. (Taiwan) 2020 [Available from: https://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/news_detail.aspx?sn=17589].

Council ND. Population Projections for the R.O.C. (Taiwan): 2018∼2065 2018 [Available from: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=84223C65B6F94D72].

Raftery AE, Li N, Sevcikova H, Gerland P, Heilig GK. Bayesian probabilistic population projections for all countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(35):13915–21.

Liou YM, Jwo CJ, Yao KG, Chiang LC, Huang LH. Selection of appropriate Chinese terms to represent intensity and types of physical activity terms for use in the Taiwan version of IPAQ. J Nurs Res. 2008;16(4):252–63.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9.

Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN international workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–60.

The Lund and Manchester groups. Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57(4):416–8.

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100.

Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1689–707 quiz 837.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the neuropsychiatric inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–9.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86.

Hebert R, Bravo G, Préville M. Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit burden interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with Dementia. Can J Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2000;19:494–507.

Schneider J, Murray J, Banerjee S, Mann A. EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: I--factors associated with carer burden. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(8):651–61.

Springate BA, Tremont G. Dimensions of caregiver burden in dementia: impact of demographic, mood, and care recipient variables. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):294–300.

Hughes TB, Black BS, Albert M, Gitlin LN, Johnson DM, Lyketsos CG, et al. Correlates of objective and subjective measures of caregiver burden among dementia caregivers: influence of unmet patient and caregiver dementia-related care needs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1875–83.

Kang HS, Myung W, Na DL, Kim SY, Lee JH, Han SH, et al. Factors associated with caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11(2):152–9.

Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, et al. Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(5):455–532.

Moïse P, Schwarzinger M, Um M-Y. Dementia care in 9 OECD countries; 2004.

Knapp M, Prince M, Albanese E, Banerjee S, Dhanasiri S, Fernandez Plotka J-L. Dementia UK: The full report. London: Alzheimer’s Society; 2007.

Dauphinot V, Delphin-Combe F, Mouchoux C, Dorey A, Bathsavanis A, Makaroff Z, et al. Risk factors of caregiver burden among patients with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders: a cross-sectional study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(3):907–16.

Hasegawa N, Hashimoto M, Koyama A, Ishikawa T, Yatabe Y, Honda K, et al. Patient-related factors associated with depressive state in caregivers of patients with dementia at home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(5):371–e15–8.

Fauth EB, Gibbons A. Which behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most problematic? Variability by prevalence, intensity, distress ratings, and associations with caregiver depressive symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(3):263–71.

Cheng ST. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64.

Fauth EB, Femia EE, Zarit SH. Resistiveness to care during assistance with activities of daily living in non-institutionalized persons with dementia: associations with informal caregivers' stress and well-being. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(9):888–98.

Rigaud AS, Fagnani F, Bayle C, Latour F, Traykov L, Forette F. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease living at home in France: costs and consequences of the disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(3):140–5.

Wimo A, Karlsson G, Sandman PO, Corder L, Winblad B. Cost of illness due to dementia in Sweden. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(8):857–61.

Williams AM, Forbes DA, Mitchell J, Essar M, Corbett B. The influence of income on the experience of informal caregiving: policy implications. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24(4):280–91.

Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, Wood J, Sands L, Dane K, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1006–14.

Chen CF, Fu TH. Policies and transformation of long-term care system in Taiwan. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2020;24(3):187–94.

Haro JM, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Bruno G, Belger M, Dell'Agnello G, Dodel R, et al. Analysis of burden in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease using self-report and supervision hours. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(7):677–84.

Miller LA, Mioshi E, Savage S, Lah S, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Identifying cognitive and demographic variables that contribute to carer burden in dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;36(1–2):43–9.

Iavarone A, Ziello AR, Pastore F, Fasanaro AM, Poderico C. Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1407–13.

Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, Lopez-Pousa S. Differential features of burden between spouse and adult-child caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an exploratory comparative design. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(10):1262–73.

Shin H, Youn J, Kim JS, Lee JY, Cho JW. Caregiver burden in Parkinson disease with dementia compared to Alzheimer disease in Korea. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(4):222–6.

Martire LM, Hall M. Dementia caregiving: recent research on negative health effects and the efficacy of caregiver interventions. CNS Spectr. 2002;7(11):791–6.

Krutter S, Schaffler-Schaden D, Essl-Maurer R, Wurm L, Seymer A, Kriechmayr C, et al. Comparing perspectives of family caregivers and healthcare professionals regarding caregiver burden in dementia care: results of a mixed methods study in a rural setting. Age Ageing. 2020;49(2):199–207.

Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655–63.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan (PH-109-GP-05, PH-108-GP-01, and PH-107-SP-13), the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 106-3114-Y-043-022, 107-2221-E-075-006-, 108-2321-B-075-001-, 109-2314-B-075-052-MY2, V110C-057). Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V108C-113, V108D43-002-MY2-1, V109C-061, VGHUST109-V1-5-1) and the Brain Research Center, National Yang-Ming University from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: CFT, WSH, CCH, JLF. Data acquisition: CFT, JJL, WFW, LCH, LKH, WJL, PSS, YCL, JLF. Data analysis: CFT, WSH, JLF. Interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: CFT, WSH. Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. JLF had full access to all data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of data analysis. The final manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent and permission for interviews and publication were received from all study participants and their main adult caregivers. The National Dementia Registry Study was approved by the ethics committees of the nine participated hospital sites (2017-06-007B) (National Health Research Institutes, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Changhua Christian Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Cardinal Tien Hospital).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, CF., Hwang, WS., Lee, JJ. et al. Predictors of caregiver burden in aged caregivers of demented older patients. BMC Geriatr 21, 59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02007-1