Abstract

Backgrounds

As the prevalence of dementia rises, caregiver burden also increases in South Korea, especially for informal family caregivers. This study aimed to analyze factors affecting caregiver burden by the severity of dementia based on data of patients in Seoul.

Methods

A total of 12,292 individuals aged ≥65 years enrolled in the Seoul Dementia Management Project from 2010 to 2016 in an online database were selected. Caregiver’s burden was assessed using the Korea version of Zarit Burden Interview. Multiple regression analyses were performed to determine factors associated with primary caregiver’s burden after stratifying the severity of dementia.

Results

Most patients showed moderate levels of cognitive impairment (49.4%), behavior problems (82.6%), and ADL dependency (73.6%). After stratifying the severity of dementia, caregivers caring for patients with mild symptoms of dementia were experienced with higher caregiver burden if patients were under a lower score of IADL. Significant factors for caregiver burden among caregivers supporting patients with moderate symptoms of dementia include caregivers’ residence with patients, subjective health status, and co-work with secondary caregivers. Lastly, caregivers for patients with severe dementia symptoms experienced a higher caregiver burden from limited cognitive function, problematic behavior, and caregivers’ negative health status.

Conclusion

In terms of sample size, this study had far more patients than any other domestic or international study. It was meaningful in that it analyzed characteristics of patients with dementia and caregivers affecting the burden of caregivers in Korea. Intensive social supports with multiple coping strategies focusing on different levels of patients’ clinical symptoms and caregivers’ needs should be planned to relieve the caregiver burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A rapidly aging society affects not only socioeconomic terms, but also puts a heavy burden of caring for patients with dementia. In South Korea, the prevalence of dementia has gradually increased. It is expected to increase from 10.16% in 2018 to 16.4% in 2050 [1] due to the high speed of population aging. The first National Dementia Management plan and the long-term care insurance for the elderly in South Korea were started in 2008. After the Dementia Management Law enacted in 2012, the National Institute of Dementia (NID) and Dementia Care Advising Service in public health center has launched a suitable healthcare service for the elderly. Since then, 12 cities and provinces nationwide have set up and operated regional a dementia center. Following national plans for patients with dementia, 256 local governments set up Dementia Safe Centers at provincial levels in 2018, with governmental financial support to prevent worsening symptoms of dementia.

Although there are some national care plans for improving the health status of patients with dementia, there is relatively little support for caregivers of patients with dementia. Distress from caregiver reflects multidimensional responses of physical, emotional, and financial difficulty related to patients’ cognitive impairment, behavioral disturbance, and limited daily activities [2]. Although several studies have mentioned the significant impact of dementia on caregiver burden, significant determinants are inconsistent. Among patient variables, psychiatric symptoms have a substantial effect on caregiver burden [3]. In some studies, behavioral problems are the most influential factors in deciding the caregiver burden [4, 5]. In cases of caregiver determinants, caregivers’ neuroticism also has an influence on caregiver burden [6, 7]. However, in contrast with this result, other studies have revealed that caregiver’s gender [8] and self-efficacy [9] decide caregiver burden.

It has been reported that caregivers for patients with dementia experience several mental health problems such as anxiety and depression [10,11,12,13]. As the prevalence of dementia rises, the burden of caregiving also increases in South Korea, especially among informal family caregivers [14]. In Korea, a filial duty under Confucian background and a lack of skilled nursing facilities put families no choice but to become informal caregivers. Although family caregivers perform their roles in taking care of patients with a sense of duty and cultural norms, they are highly likely to show degraded quality of life and suffer psychological distress. Therefore, it is important to analyze factors associated with patients with dementia that may influence the caregiver burden [15, 16]. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine effects of characteristics of patients with dementia and their caregivers on caregiver burden in Korea.

Methods

Study settings

Seoul Dementia Management Project (SDMP) provides comprehensive healthcare programs under the supervision of Seoul Metropolitan Center for Dementia (SMCD) [17]. The SDMP emphasizes community-based integrative management for dementia, which encompasses education, preventive programs, early detection, therapeutic interventions, and proper care services that are closely linked to online case-registration & management systems. The online database from SDMP provides socio-demographic characteristics of patients, results of screening examination, and history of care programs such as detailed information of services to prevent worsening dementia symptoms, improve patients’ cognitive function, and provide social support for patients’ families.

Participants

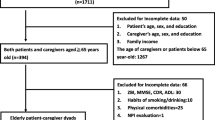

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, a generally used dementia staging instrument, was used by a panel of neurologists and psychiatrists from 25 districts of Dementia Safe Centers. CDR score was assessed using a collected clinical instrument during phase 1 and phase 2. This study followed global CDR criteria, a 5-point ordinal scale. CDR scores of 0.5 ~ 1, 2, and 3 refer to mild, moderate, and severe dementia, respectively, while CDR 0 indicates no dementia. In phase 1, a trained nurse performed a mental status examination to identify cognitive impairment. The cognitive impairment group had completed either Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease or Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery [18]. In phase 2, neurologists and psychiatrists diagnosed patients’ symptoms under the basis of clinical assessment or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV. Therefore, a total of 12,292 patients were analyzed after excluding those who had no information about their major caregiver (38,055), no Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) information (1527), and patients with no dementia (CDR = 0) [19] from 51,908 patients from 2010 to 2016 in an online database (Fig. 1).

Severity of dementia

The severity of dementia was assessed with the Seoul Dementia Assessment Packet (SDAP), a brief screening instrument that was developed to screen patients’ symptoms and caregiver burden in multidimensional aspects. SDAP was used to evaluate patients’ symptoms based on the summary score of cognitive impairment, Behavioral And Psychological Symptoms In Dementia (BPSD), Activities of Daily Living (ADL), and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [20].

Tools used for assessing the functional ability of patients with dementia are as follows. Cognitive impairment was measured by four items: memory, orientation, problem-solving, and communication skill. The severity of cognitive impairment was categorized into three levels based on total scores from the questionnaire: mild (0–4), moderate [5,6,7,8], and severe [9,10,11,12]. The severity of BPSD included six domains: delusion, hallucination, agitation, apathy, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and sleep disturbance. The severity of BPSD was classified into three categories after summing scores from each questionnaire: mild (score of 0 ~ 6), moderate (score of 7 ~ 12), and severe (score of 13 ~ 18). ADL consisted of nine items: bathing, dressing, grooming, mouth care, walking, climbing stairs, eating, transferring bed or chair, and getting toilet hygiene. The severity of ADL was determined as follows. Patients who gained a total score of 0 to 9 were considered to have mild symptoms. Those with a total score of 10 to 18 and 19 to 27 were defined as having moderate and severe symptoms, respectively. IADL included seven areas: ability to use a telephone, laundry, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, taking medication, and handling finances. The severity of IADL was classified into three categories: mild (score of 0–7), moderate (score of 8–14), and severe (score of 15–21).

Caregiver burden

Korea version of Zarit Burden Interview (ZBH-K) was used to measure caregiver burden [21]. Trained nurses were educated about burden interviews in advance. They recorded responses of caregivers during a 1:1 interview. Assessment tool was comprised of 22 domains, ranging from a score of 0 (not at all) to a score of 4 (have always been).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations. A chi-squared test was used to test the relationship between categorical variables. Multiple linear regression was used to analyze the relationship between CDR and characteristics of patients and caregivers. Patients’ CDR was used as a dependent variable which was stratified by severity level of dementia symptoms. All variables included in the bivariate analysis were entered in the multiple linear analysis except for patients’ and caregivers’ marital status and caregivers’ educational level. The marital status of the patients had strong collinearity with residence type. Therefore, we replaced marital status to residence type as one of the entry variables to understand the relationship between caregiver and patient. The reason for not including caregivers’ educational level is because more than 2000 caregivers did not answer for their education experience. Additionally, when we added the caregivers’ educational level to the regression model, no level of education was statistically significant, and the regression model was not improved. The number of missing in both patients’ and caregivers’ marital status were not large as that of caregivers’ educational level. However, it was not included in the model because of the same reason with the caregivers’ educational level.

SPSS version 20.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. The probability level indicating statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients with dementia

Table 1 shows general characteristics of patients with dementia. The average age of patients was 80.5 years. The majority (68.4%) of them were females, which was twice as many as males (31.6%). The highest percentage was found for those with at least elementary education (36.9%) regarding education level, those who were bereaved (53.8%) regarding marriage status, those who were co-residing with other family members (36.9%) regarding co-resident type, and those who had no religion (36.5%) regarding religion status. Among patients classified by the severity of dementia, most patients had at least CDR 1 level (70.6%), followed by those with CDR 2 (18.5%) and CDR 3 (10.9%).

Results of SDAP

Results of SDAP are shown in Table 2. Most patients showed a moderate level of cognitive impairment (49.4%), behavior problems (82.6%), and ADL dependency (73.6%). However, a severe level of IADL dependency was the most frequent case (40.5%) among patients.

Characteristics of caregivers

As shown in Table 3, most (68.5%) caregivers were females with an average age in the early 40s to late 50s (49.9%). They had 10 years to 12 years of upper secondary education (27.9%), co-residing with patients (63.8%), non-religion (45.8%), married (80.5%), unemployed (56.3%), and a moderate level of self-rated health status (56.0%). Mostly daughters were taking care of patients (27.8%) with no secondary caregiver (57.5%).

Determinants of caregiver burden

General characteristics of patients with dementia and caregivers were used as independent variables in multiple regression analysis to identify significant factors affecting caregiver burden (Table 4). Before stratifying the severity of dementia, significant determinants of patients and caregivers were as follows. Male patients (β = − 1.396), and living with spouse and other family members (β = − 1.487) or others such as friends or volunteer workers (β = − 6.889) showed negative relationships with caregiver burden. Caregivers who were not co-residing with patients (β = − 3.769), who had Christian religion (β = − 1.071), who had no family relationship with patients (β = − 1.795), who answered that their recent health status was more than moderate (moderate: β = − 7.019, good: β = − 10.299), and who shared their works with secondary caregivers (β = − 2.399) showed similar results. However, patients with cognitive impairment (β = 1.312), limited ADL (β = 0.072), limited IADL (β = 0.698), and severe BPSD (β = 1.545) had positive relationships with caregiver burden. In the case of caregiver characteristics, those who were females (β = 3.386) or having parent and child relationships (daughter: β = 1.838, son: β = 2.835) had more caregiver burden.

After stratifying the severity of dementia, results of CDR 1 were similar to overall patients’ caregiver burden. However, in case of CDR 2, patients who were living with others (β = − 6.451), caregivers who were not cohabitating with patients (β = − 4.706), who had moderate (β = − 7.452) or good (β = − 10.380) health status, or those who were working with secondary caregivers (β = − 3.460) showed less caregiver burden. On the other hand, female caregivers (β = 1.131) or patients who had limited IADL (β = 0.267) and severe BPSD (β = 1.368) had positive relationships with caregiver burden. Results of CDR 3 showed that patients who were co-residing with others (β = − 5.720) and caregivers who answered their health status as moderate (β = − 9.470) or good (β = − 9.924), and who were living independently with patients (β = − 5.726) showed less caregiver burden. In contrast with this, patients who were experiencing cognitive impairment (β = 0.806) or severe BPSD (β = 1.206) and female caregivers (β = 4.172) showed more burden.

Discussion

This study analyzed relationships between caregiver burden and characteristics of patients with dementia and caregivers. A total number of 12,292 patients were analyzed, which outnumbered previous studies from Korea (609) and other countries (732) [22,23,24]. In this study, female patients were twice as many as male patients [25,26,27,28] because the prevalence of dementia had a positive relationship with age. In addition, life expectancy was different by gender.

Results also showed that 70% of patients had mild severity, implying that patients with more than moderate severity were residing in a nursing home while patients with mild severity were using SCD as an outpatient service. It was found that 41% of patients were residing with a spouse or other family members while 37% of patients were bereaved but living with other extended families. These results suggest that cultural background such as a strong Confucianism in Korea can influence patients’ family to be a major informal caregiver and accelerate caregiver burden [29].

Patients with worse cognitive functions and IADL were heavily relying on their caregivers. About 26% of them needed assistance for most of their daily activities. This finding suggests that most patients need the help of caregivers to keep their daily living, such as preparing a meal, taking medications, and managing financial statements due to their lack of ability to do so [30].

While taking care of patients with dementia, caregiver burden might exacerbate according to characteristics of caregivers. Considering that the mean age of caregivers was in the 60s, elderly care by elderly baby boomers not only could aggravate caregiver burden, but also could cause socioeconomic concern due to extensive health service use and unmet need [31]. Among patients’ SDAP evaluation criteria, cognitive impairment and limited IADL had significant relationships with caregiver burden. In particular, caregiver burden increased when patients were experiencing severe BPSD. Therefore, it would be critical to apply BPSD intervention programs for efficient patient care, consistent with findings of previous studies [32,33,34].

In addition to characteristics of patients, caregiver burden was related to determinants of caregivers. Male caregivers and those who were not residing with patients had a relatively lower caregiver burden. These results suggest that caregivers may be overwhelmed by the overly long working time for supporting patients with dementia. Therefore, proper allocation of caregivers’ work should be considered as one of the measurements for solving caregiver burden issues. Governmental strategies, considering caregivers’ self-rated health status and their patients’ clinical symptoms, should be arranged to relieve the caregiver burden. Intensive social support and social networks for caregivers are essential for solving the caregiver burden [19]. In particular, differentiated policy supports such as patients’ cognitive or behavioral problem-focused coping strategies or caregivers’ emotion-focused programs depending on caregivers’ needs, rather than applying the same coping plans [35], should be implemented considering the severity of patients’ clinical symptoms and caregivers’ situational coping strategies for more effective interventions.

After stratifying the severity of dementia, significant factors related to caregiver burden were different for each level of severity. Caregivers’ gender was a significant factor determining caregiver burden among patients with mild and severe severity, but not for those with moderate dementia symptoms. In contrast with this, having a secondary caregiver was related to less burden of caregivers for patients with mild and moderate severity of dementia, but not for those with severe dementia. The reason for such results might be because most patients with more than moderate severity were bedridden that required intensive care most of the time. Therefore, it would be more efficient to organize and apply health promotion program for patients with dementia and their caregivers based on dementia severity [36].

Lastly, caregivers for patients with severe dementia symptoms experienced a higher caregiver burden from patients’ limited cognitive function, problematic behavior, and caregivers’ negative health status. This implies the importance of supporting the health of caregivers for patients with severe symptoms of dementia, suggesting both physical and psychological health intervention programs for managing caregivers’ health status are needed [22, 37].

This study had some limitations. Firstly, most study participants were home-based patients recruited from an online database of SDMP. In addition, most (around 70%) study participants had mild symptoms. Thus, general characteristics of total patients might reflect traits of patients with mild severity. Therefore, results of this study could be only applied to a limited range of patients with dementia. Secondly, although a trained nurse had taken a series of training courses to measure caregiver burden, there might be observer variations. Also, some possible factors such as hours of caregiving, caregivers’ self-efficacy, and type of coping strategies could be included in this study due to limited information. Additionally, this study excluded participants who have no caregiver, CDR, or SDAP information or CDR scored 0. Considering the potential significance of their characteristics, the results of this study should be carefully interpreted. Nevertheless, this study had a strength in that it analyzed the relationship between caregiver burden and possible determinants considering both characteristics of patients with dementia and their caregivers in Korea with a large sample size. In particular, this study emphasized the importance of caring for the elderly since the elderly would become a grave social burden issue in the geriatric public health sector.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the relationship between caregiver burden and socio-demographical characteristics of patients with dementia and caregivers by the severity of dementia symptoms. Results of analysis of 12,292 individuals enrolled in the Seoul Dementia Management Projects from 2010 to 2016 showed that gender was a significant factor affecting the burden of caregivers for patients with moderate or severe dementia symptoms. Additionally, secondary caregivers’ assistance was related to the burden of caregivers for patients with mild to moderate symptoms of dementia. However, caregivers’ self-rated health status and co-residence with patients also showed significant relationships with burden of caregiver for patients with severe symptoms of dementia.

This study demonstrated that caregivers taking care of patients with dementia experienced different levels of caregiver burden according to their socio-demographical characteristics and patients’ clinical and socio-demographical characteristics. In particular, caregivers’ health should be considered to prevent caregiver burden. Therefore, social supports with multiple coping strategies focusing on different levels of patients’ clinical symptoms and caregivers’ needs should be given. Governmental supports such as expanding beneficiaries for caregivers’ health management programs or providing secondary caregivers for mitigating caregivers’ workload would be essential.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Seoul Metropolitan Center for Dementia. However, restrictions may apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, as they are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Seoul Metropolitan Center for Dementia.

Abbreviations

- NID:

-

The National Institute of Dementia

- SDMP:

-

Seoul Dementia Management Project

- CDR:

-

Clinical Dementia Rating

- SDAP:

-

Seoul Dementia Assessment Packet

- BPSD:

-

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- ZBH-K:

-

Korean version of Zarit Burden Interview

References

Kim KW KB, Kim SY, Kim SG, Kim JR, Kim TH, et al.. Nationwide survey on the epideiology of Korea.: Korea Ministry of Health & welfare; 2012.

Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26(3):260–6.

Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos CG, Schneider LS. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(10):917–27.

Aminzadeh F, Byszewski A, Dalziel WB. A prospective study of caregiver burden in an outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment program. Clin Gerontol. 2006;29(4):47–60.

Bédard M, Kuzik R, Chambers L, Molloy DW, Dubois S, Lever JA. Understanding burden differences between men and women caregivers: the contribution of care-recipient problem behaviors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17(1):99.

Campbell P, Wright J, Oyebode J, Job D, Crome P, Bentham P, et al. Determinants of burden in those who care for someone with dementia. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(10):1078–85.

Allegri RF, Sarasola D, Serrano CM, Taragano FE, Arizaga RL, Butman J, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as a predictor of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2(1):105.

Bédard M, Molloy DW, Pedlar D, Lever JA, Stones MJ. Associations between dysfunctional behaviors, gender, and burden in spousal caregivers of cognitively impaired older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(3):277–90.

Cheng ST, Lam LC, Kwok T, Ng NS, Fung AW. Self-efficacy is associated with less burden and more gains from behavioral problems of Alzheimer’s disease in Hong Kong Chinese caregivers. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):71–80.

Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G. Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):929–36.

Pioli MF. Global and caregiving mastery as moderators in the caregiving stress process. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(5):603–12.

Rabinowitz YG, Mausbach BT, Gallagher-Thompson D. Self-efficacy as a moderator of the relationship between care recipient memory and behavioral problems and caregiver depression in female dementia caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):389–94.

Wu HZY, Low LF, Xiao S, Brodaty H. Differences in psychological morbidity among Australian and Chinese caregivers of persons with dementia in residential care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1343–51.

Kwon OD, Kim TW, Park MY, Yi S-D, Yi H-A, Lee HW, et al. Factors affecting caregiver burden in family caregivers of patients with dementia. Dement Neurocogn Dis. 2013;12(4):107–13.

Burgener S, Twigg P. Relationships among caregiver factors and quality of life in care recipients with irreversible dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(2):88–102.

Morimoto T, Schreiner AS, Asano H. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among Japanese stroke caregivers. Age Ageing. 2003;32(2):218–23.

Lee DY. Seoul dementia management project and Seoul metropolitan center for dementia. J Korean Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;11(1):8.

Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean version of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease assessment packet (CERAD-K) clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(1):P47–53.

Epstein-Lubow G. Family caregiver health: what to do when a spouse or child needs help. Med J Rh Island. 2009;92(3):106.

Lee Y, Jung KJ, Kim JH, Lee SJ, Choe YM, Byun MS, et al. Development and validation of the Seoul dementia assessment packet (SDAP). Alzheimer's Dementia. 2015;11(7):P459–P60.

Yoon E, Robinson M. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the Zarit burden interview (K-ZBI): preliminary analyses. J Soc Work Res Eval. 2005;6(1):75.

Han SJ, Lee S, Kim JY, Kim H. Factors associated with family caregiver burden for patients with dementia: a literature review. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2014;16(3):242–54.

Han JW, Jeong H, Park JY, Kim TH, Lee DY, Lee DW, et al. Effects of social supports on burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(10):1639–48.

Brodaty H, Woodward M, Boundy K, Ames D, Balshaw R, Group PS. Prevalence and predictors of burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(8):756–65.

Kim JS, Kim MS, Kim SO, Yoo YJ, Won DY. Factors influencing dementia Caregivers' health-related quality of life. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2007;18(2):232–41.

Kim H, Chang M, Rose K, Kim S. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(4):846–55.

Lee Y, Park M. Factors Influencing Caregiving Satisfaction among Family Caregivers of Patients with Dementia. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2016;18(3):117–27.

Shaji K, George RK, Prince MJ, Jacob K. Behavioral symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):45.

Kim JS, Park NH, Kim MS. Development of a Korean senile dementia management model. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2004;15(3):450–9.

Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Frey MT, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, et al. Executive function and instrumental activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):300–8.

Bell CM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ. The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(3):129–36.

Kwon OD, Kim TW, Park MY, Yi S-D, Yi H-A, Lee HW. Factors affecting caregiver burden in family caregivers of patients with dementia. Dementia Neurocogn Disord. 2013;12(4):107–13.

Bae K, Shin I, Kim S, Kim J, Yang S, Mun J, et al. Care burden of caregivers according to cognitive function of elderly persons. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2006;12(1):66–75.

Melo G, Maroco J, de Mendonça A. Influence of personality on caregiver's burden, depression and distress related to the BPSD. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(12):1275–82.

Sun F. Caregiving stress and coping: a thematic analysis of Chinese family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia. 2014;13(6):803–18.

Mioshi E, Foxe D, Leslie F, Savage S, Hsieh S, Miller L, et al. The impact of dementia severity on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(1):68–73.

Andrén S, Elmståhl S. Relationships between income, subjective health and caregiver burden in caregivers of people with dementia in group living care: a cross-sectional community-based study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(3):435–46.

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted by analyzing secondary data after obtaining approval for the use of data managed by Seoul Metropolitan Center for Dementia.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK designed the study, performed the data analyses, and prepared the manuscript. She is co-author #1 who defined the overall study method and interpreted the results. JK provided guidance for the discussion section of the article and reviewed the article for editing purposes. She is co-author #2 who reviewed the paper, proposed various refinements for the study, and proposed the core scientific idea to improve the paper. NH evaluated the methodological quality of study and provided critiques for the discussion section of this article. KL evaluated the methodological quality of study and critically revised overall contents of the manuscript. KC performed the data analysis and evaluated the methodological quality of study. SK contributed to the interpretation of the results and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Songeui Campus, the Catholic University of Korea (IRB approval no., MC17EESI0034). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B., Kim, J.I., Na, H.R. et al. Factors influencing caregiver burden by dementia severity based on an online database from Seoul dementia management project in Korea. BMC Geriatr 21, 649 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02613-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02613-z