Abstract

Background

Disturbances in sleep and circadian rhythms are common among residents of long-term care facilities. In this systematic review, we aim to identify and evaluate the literature documenting the outcomes associated with non-pharmacological interventions to improve nighttime sleep among long-term care residents.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews guided searches of five databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) for articles reporting results of experimental or quasi-experimental studies conducted in long-term care settings (nursing homes, assisted-living facilities, or group homes) in which nighttime sleep was subjectively or objectively measured as a primary outcome. We categorized each intervention by its intended use and how it was administered.

Results

Of the 54 included studies evaluating the effects of 25 different non-pharmacological interventions, more than half employed a randomized controlled trial design (n = 30); the others used a pre-post design with (n = 11) or without (n = 13) a comparison group. The majority of randomized controlled trials were at low risk for most types of bias, and most other studies met the standard quality criteria. The interventions were categorized as environmental interventions (n = 14), complementary health practices (n = 12), social/physical stimulation (n = 11), clinical care practices (n = 3), or mind-body practices (n = 3). Although there was no clear pattern of positive findings, three interventions had the most promising results: increased daytime light exposure, nighttime use of melatonin, and acupressure.

Conclusions

Non-pharmacological interventions have the potential to improve sleep for residents of long-term care facilities. Further research is needed to better standardize such interventions and provide clear implementation guidelines using cost-effective practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many long-term care residents have sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances [1, 2] due to advanced age, the effects of certain chronic illnesses and medications, declining brain health, diminished mobility, and other causes [3, 4]. Therefore, the American Geriatrics Society and the National Institute on Aging now recognize a geriatric syndrome in which physical and mental risk factors overlap to increase risk for sleep and circadian disturbances. The relationship between some risk factors and sleep disturbance is often bidirectional [3]. Numerous negative consequences are associated with sleep disturbances, including increases in cognitive decline, metabolic disease, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease mortality, frailty, impaired quality of life, and hypersensitivity to pain [3].

Long-term care residents have a high prevalence of multimorbidity that includes both chronic physical (e.g., advanced cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, arthritis) and mental (e.g., dementia, depression) illnesses that are associated with sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances [4, 5]. More than a quarter of nursing-home residents and approximately 70% of assisted-living facility residents have been diagnosed with dementia [5, 6], and almost half of those will have sleep disturbance [7, 8]. Sleep disturbance in dementia patients is associated with anxiety and behavioral symptoms of agitation, aggressiveness, and disinhibition [7]. Sleep disturbances and accompanying symptoms often lead providers to prescribe psychoactive medications, including hypnotics. Sedative-hypnotic pharmaceuticals are commonly used for assisted-living facility residents with dementia [9]. Similarly, about 47% of nursing-home residents with dementia are prescribed sedative-hypnotics, especially when displaying anxiety and agitation [10].

However, both benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics have been associated with an increased risk of fall and fractures in older adults [11,12,13]. These challenges reinforce the need to consider non-pharmacological approaches in the unique physical environment and institutional milieu of long-term care facilities [14]. The potential for sleep or circadian rhythm disturbance is linked to an increase in vulnerability to environmental challenges in these facilities [1]. For some residents, a non-stimulating environment may lead to excessive daytime and early evening napping that would exacerbate sleep disturbances. Others may experience an over-stimulating nighttime environment due to light and noise or exposure to disruptive behaviors, including pain, discomfort, repetitive vocalizations, and wandering. Staff routines such as nighttime incontinence care are also disruptive to sleep maintenance [15].

The problems associated with existing pharmacological treatments, coupled with institutional environments that can further disrupt sleep, mean that non-pharmacological interventions should be considered to help prevent or manage sleep disturbance [16]. Consistent with recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society and the National Institute on Aging [3], the objective of this systematic review is to identify and evaluate the literature documenting the outcomes associated with non-pharmacological interventions to improve nighttime sleep among long-term care residents.

Methods

Our original intent for this systematic review was to evaluate the literature addressing non-pharmacological interventions to promote sleep among adults across all institutional settings. As described below, our search was adjusted to focus on long-term care settings due to important differences between acute-care and residential settings, such as high medical acuity and short length of stay.

Search methodology

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement was used to guide this review [17]. A library specialist (KP) performed systematic searches of MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Scopus (Elsevier), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley) between August and October of 2016, with weekly search updates for all five databases through December 2016. Major search terms for all databases were represented by both controlled vocabulary and keywords (Table 1) on the topic of sleep quality in institutional healthcare settings. Where appropriate, searches were restricted to human, adult, English-language studies but were not otherwise limited by study design or date of publication. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2 for the original systematic review. Studies were then further limited to those located in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care facilities. The complete search strategies are available in the supplemental materials (Additional file 1: Table S1- Search Strategies-BMC).

Study selection, data extraction, and analysis

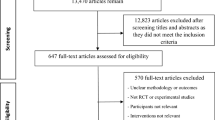

After the removal of duplicates, the final set of 6747 articles was transferred to Covidence software for synthesis of the literature data. Two review authors (AB and NJ) independently assessed the eligibility of the retrieved articles by title and abstract. A third author (EC, RZ or AK) resolved all conflicts, with a total of 6302 articles excluded. The library specialist downloaded full-text versions of the remaining 445 articles. Teams of two review authors (AB, NJ, RZ or EC) then independently assessed the eligibility of the full-text articles. Any conflicts at this stage were resolved by another author (AK). Applying the exclusion criteria to this body of literature, another 311 articles were removed. The major reasons for exclusion, in order of frequency, were literature review, presentation abstract, wrong patient population, editorial, wrong outcomes (not sleep), and wrong setting.

The resulting set of 134 articles was split between hospital-based studies (n = 79) and the final set of 54 articles focusing on long-term care settings that we used in this analysis. We used the details from the selection process in Covidence to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) [17] and exported all titles and abstracts to EndNote software. Two review authors (AB and NJ) independently extracted study characteristics in Microsoft Excel and then summarized the characteristics of the included studies. A second review author (RZ or EC) checked the accuracy of the table against the original articles.

We revised the intervention coding we used for an integrative review conducted by this research team that focused on non-pharmacological intervention for sleep in patients with advanced serious illness for this reviews’ population of long term care residents [18]. We used an iterative approach to code interventions. First, we examined the intent of the intervention, such as what risk factor for sleep disturbance was targeted for reduction or elimination (e.g., daytime physical exercise to address excessive daytime napping). The categories that emerged from the data were mostly interventions manipulated by staff or study personnel: environmental factors (external to the resident), complementary health practices (touch and oral supplements), social and physical stimulation (activities for exercise or engaging the resident cognitively), and clinical care practices (reducing sleep disruptions). The final category, mind-body practices, are those in which residents actively participate and include activities such as self-relaxation and meditation.

After evaluation of the interventions and intended outcomes, we then determined their overall effect on actual outcomes related to sleep disturbance. We categorized interventions as having a positive effect, a mixed effect (some positive and some inconclusive outcomes), no effect, or a negative effect. Our overall summary of the findings was based on nighttime sleep outcomes, although some studies also reported daytime sleep results. The risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias methodology for randomized clinical trials [19] and the Summary Quantitative Studies and Critical Appraisal Checklist for all other studies [20].

Results

Study characteristics are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 (multicomponent). Of the 54 studies, more than half employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design (n = 30); the others used a pre-post design with (n = 11) or without (n = 13) a comparison group.

Sites and participants

The 54 studies included 3627 participants residing in nursing homes (n = 42), assisted-living facilities (n = 11) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], and one elderly residential setting [32]. The facilities were located mostly in the United States (n = 25), Europe (n = 14) or Asia (n = 10). Most studies investigated one (n = 23) or two (n = 11) long-term care facilities, with a range from 1 to 20. The mean sample size was 66.5 patients (standard deviation [SD] = 58.6), with a range from 5 to 267 participants. The mean age was 81.9 years (SD = 4.4), and the study populations were 41.1% female on average. More than half (52%) of the studies included participants with dementia [23, 24, 27, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], and six studies targeted patients with known sleep problems [28, 30, 49,50,51,52].

Measures

More than half (n = 28) of the included studies objectively measured sleep with wrist actigraphy or a daysimeter (measures both light and activity) [53], and one study supplemented these findings with polysomnography [54]. Two studies used polysomnography exclusively [26, 55]. The remainder used self-reporting or reports completed by research or clinical staff, most frequently with the valid and reliable Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (n = 11) [22, 28, 32, 38, 49, 50, 56,57,58,59,60].

Quality assessment

The risks of bias for randomized clinical trials and all other quantitative studies are summarized in Tables 5 (n = 30) and 6 (n = 24), respectively. Risks of bias for individual studies are available in the supplemental materials (Additional file 2: Table S2-BMC and Additional file 3: Table S3-BMC). Among the 30 RCTs, most studies had a low (n = 11) or unclear (n = 15) risk of selection bias, and a majority (n = 28) had a low risk of reporting bias because there was clarity in the reporting of all pre-specified outcomes. Most studies were at low risk for detection (n = 21) and attrition (n = 19) bias. However, only 7 studies were deemed at low risk for incomplete outcome data for periods longer than 6 weeks because most studies only reported data in the immediate post-intervention period. Regarding performance bias, 9 studies were at high risk because it was not possible to blind anyone to the intervention.

For the 24 non-RCTs, most (n = 20) studies met at least 12 of the 17 criteria deemed most important for quality appraisal. Many studies, however, did not describe the statistical power of the study (n = 19), mention piloting of the intervention (n = 13), use valid or reliable measures (n = 8), or overstated study conclusions (n = 13). Few presented the ethical considerations of the study procedures or intervention (n = 19) (Table 6).

Outcomes

Most studies indicated positive findings (n = 24) of non-pharmacological interventions in improving nighttime sleep outcomes [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 30, 32, 34, 39, 42, 44, 48,49,50, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63] whereas 11 studies reported mixed findings (both positive and none) [29, 31, 36, 43, 45,46,47, 51, 53, 64, 65]. Although reporting other positive outcomes, 19 studies found no change in nighttime sleep quality after the intervention [33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 52, 54,55,56, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. The results differed among location sites, with studies conducted in assisted-living facilities reporting a higher proportion of positive findings than those in nursing homes (70 and 35.7%, respectively).

Study outcomes by intervention type

The interventions employed in the studies varied widely and included interventions in the following categories: clinical care practices (n = 3), mind-body practices (n = 3), social/physical stimulation (n = 11), complementary health practices (n = 12), and environmental interventions (n = 14). There were a total of 25 individual (same type, though differences in dose) interventions; 15 studies employed either a combination of interventions within a specific category (n = 4) or a multicomponent intervention consisting of two or more categories of non-pharmacological intervention (n = 11). The following sections summarize the results for each intervention category (Table 3).

Clinical care practices (n = 3) [25, 41, 73]

Practices implemented by nurses included administering a warm evening foot bath to adjust core body temperature [73], providing individualized care (e.g., residents have choice regarding bedtime) [41], and minimizing nighttime disruptions [25]. These interventions had no, mixed, and positive findings, respectively. All three studies used a pre-post design with sample sizes of 30, 33, and 18, respectively, and none of the authors described sample size calculation. All three studies used quasi-experimental designs, with only one including a comparison/control group as well as objectively measuring sleep with actigraphy [73]. Seven multicomponent studies utilized the clinical care practices of minimizing clinical disruptions [44, 45, 54, 65] and/or sleep-wake time management [34, 52, 54, 65]. Among these multicomponent studies, six incorporated clinical care practices to minimize disruptions [44, 45, 54, 65] and/or manage sleep-wake [34, 52, 54, 65].

Mind-body practices (n = 3) [22, 50, 58]

These interventions require some active involvement by the participant, and each of the three studies included only cognitively intact residents. One study was conducted with assisted-living facility residents in Taiwan [22]; the other two were in nursing homes in Egypt [50] and Turkey [58]. Two relaxation strategies had positive results: progressive muscle relaxation [58] and the meditative practice of yoga [22]. This was an adaptation of hatha yoga specifically developed for the reduced flexibility and exercise tolerance of older adults. All three were well-conducted, quasi-experimental studies using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index subjective measure. However, the study examining cognitive-behavioral therapy did not include a comparison group [50]. No mind-body practices were used in the multicomponent studies.

Social and physical stimulation (n = 11) [23, 26, 32, 33, 42, 43, 46, 51, 55, 57, 67]

Eleven studies utilized interventions that prompted participants to engage in a physical or social activity meant to stimulate cognition, mobility, or both. The latter included three RCTs using actigraphy [51] or polysomnography [26, 55] with low risk of bias; however, the findings were not consistent, with positive [26], none [55], and mixed findings [51]. Of three studies testing social and cognitive activities on nursing-home residents with dementia, one reported improved sleep [42], and the other two studies reported mixed findings [43, 46]. The remaining five studies employed physical exercise/activity and varied in quality. Three studies reported improved sleep [23, 32, 57] and two reported no changes in sleep [32, 33]. Six multicomponent studies included physical activity.

Complementary health practices (n = 12) [21, 28,29,30, 47, 48, 59, 60, 62, 68, 69, 74]

These are interventions that originated outside mainstream medicine, are administered by a practitioner or clinical staff member, and are received by touch, smell, or ingestion. Two studies examining the effect of massage alone [69, 74] did not find improvements in sleep, and one study combining massage with lavender aromatherapy [29] reported mixed findings. Other touch modalities positively improved sleep, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [48] and therapeutic touch [62]. However, these studies tested only 14 and 6 participants, respectively. Of the four studies of acupressure, three employed a RCT design with low risk of bias [21, 30, 59], while the fourth evaluated 8-h continuous acupressure using a pre-post design with 129 residents [60]. All four reported positive sleep outcomes. The three studies evaluating melatonin use reported no change in sleep (melatonin dose: 8.5 immediate + 1.5 mg sustained release) [68], mixed findings (melatonin dose: 5 mg to 20 mg of melatonin-rich milk) [41], and better sleep (5 mg + magnesium and zinc) [28]. Two multicomponent RCTs included melatonin (2.5 mg and 5 mg) and found positive [27] and no [66] changes in sleep, respectively.

Environment (n = 14) [24, 31, 35,36,37,38, 40, 49, 53, 56, 61, 63, 64, 71]

With the exception of one study evaluating the use of a medium-firmness mattress (no improvement in sleep) [56], all studies of the environment focused on increasing light exposure via natural (outdoor) [38, 63] or bright artificial light illumination during the day. The “dose” of light varied considerably from 2500 lx to 10,000 lx administered for 30 min to 8 h per day for 10 days to 10 weeks. It was not possible to correlate dose with findings of no [35,36,37,38, 40, 71], positive [24, 49, 61, 63], or mixed [31, 36, 53, 64] improvement in sleep outcomes. Similarly, there was no relationship between study design/risk of bias and outcomes. Light was also included in most (n = 8) multicomponent studies, using either natural light [39, 52, 65, 72] or a bright light source of 2500 lx to 10,000 lx [27, 54, 66, 70] for a range of time periods.

Multicomponent (n = 11) [27, 34, 39, 44, 45, 52, 54, 65, 66, 70, 72]

Table 4 provides a summary of the characteristics and components of each multicomponent intervention. These studies included an average of 3 (SD = 1.2) interventions with a range of 2 to 5. All included an environmental intervention: increased light (n = 8) [27, 39, 52, 54, 65, 66, 70, 72] and/or reduced noise (n = 5) [34, 44, 45, 54, 65]. Three included the use of melatonin [27, 66] or a vitamin B12 supplement [70]. Two studies included 5 interventions (light, noise, activity, fewer disruptions, and sleep-wake management) [54, 65], and two other studies investigated 4 interventions (light, noise, individual care, and sleep-wake management) [44, 45], but the findings were not consistent. Physical activity was investigated in six studies [34, 39, 52, 54, 65, 72], and four studies employed the clinical care practices of individual care [44, 45], fewer disruptions [44, 45, 54, 65], and sleep-wake management [34, 52, 54, 65]. Most studies (n = 9) were RCTs, and many of these had a low risk of bias [27, 45, 52, 54, 65]. No clear pattern of intervention combinations emerged among studies with no [52, 54, 66, 70, 72], positive [27, 34, 39, 44], or mixed [45, 65] effect on sleep. The highest proportion of RCTs with several areas of high risk of bias was found among this category of studies [34, 45, 52, 54, 65, 72].

Discussion

Despite the minimization of the use of physical restraint, the promotion of function-focused care, and the growing trend of culture change in nursing homes, residents spend considerable time inactive, including large amounts of time in bed [75, 76]. Moreover, the institutional environment provides little opportunity for residents to synchronize their circadian clock to the solar day, which is necessary to support alertness during the day and the consolidation of sleep at night. During the night, residents may experience frequent awakenings and fragmented sleep from clinical care practices that increase light and noise. These factors together contribute to the sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances frequently encountered among long-term care residents. In this systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions to improve sleep among long-term care residents, it was found that nearly three-quarters (n = 37) of the studies aimed to normalize circadian rhythms by increasing daytime activity (100% of social and physical stimulation category), increasing daytime light (93% of environment category), improving nighttime staff routines to minimize disruptions (67% of clinical care practices), or a combination of these interventions (100% of multicomponent). Although there is sound evidence to support these strategies, the variation in how the interventions were delivered (type of daytime activity or dose of light) reduces the ability to draw definitive conclusions.

Given the functional and cognitive limitations of long-term care residents, it is not surprising that the most frequently studied interventions were largely passive in nature: environmental interventions, complementary health practices, and social/physical stimulation. Daytime light therapy was highly correlated with improved sleep [77], including in those with dementia [78], but more evidence-based guidance is needed regarding dose, delivery, frequency, and duration [79]. Because exposure to natural daylight is often not feasible due to location or building design, supplementing the environment with bright artificial light is a feasible option. Current room lighting systems that eliminate safety concerns (excessive heat or UV rays) can be incorporated in high-use areas such as day and dining rooms. However, this intervention was not found in this review. Other environmental interventions, such as control of ambient temperature with a cooler nighttime temperature, were not found in this review and deserve to be explored in future research [80].

Many single and most multicomponent studies also aimed to “reset” residents’ circadian rhythm with stimulating activities during the day and/or strategies that promote relaxation or deter sleep disruption at night. Fewer than half of those studies that tested either exercise or passive social stimulation reported positive findings [23, 32, 34, 39, 42, 57], although several were well-executed RCTs [26, 39, 57]. Most were conducted by research staff to establish intervention efficacy; thus, translating these time-consuming strategies to current staff levels and roles needs careful consideration. The low number of studies directed toward changing clinical care practices to promote sleep suggests difficulty in altering entrenched routines [52]. These concerns underscore the need to consider intervention feasibility in a low-resource practice environment. A community-participatory approach that actively includes equitable input from long-term care staff, residents, and their families may be needed to overcome challenges to practice change [81]. For example, there is considerable evidence to support acupressure [82], but further research is needed with nursing staff to understand how easily (or not) this practice could be incorporated within their nighttime care routines. Another aspect of feasibility that was absent from the reviewed studies is a cost/benefit analysis, which is needed for buy-in from administrators.

Complementary health practices, although not commonly employed in nursing homes, represented more than a quarter of the included studies and were associated with a high proportion of positive outcomes for both acupressure and melatonin in well-executed studies. Although there were no consistent findings with melatonin in this review, possibly because the dose regimen was quite variable, melatonin is considered a safe and effective approach to improve sleep in older adults [83], including those with dementia [84].

Because some of the studies evaluating mind-body techniques were performed in nursing homes outside the United States, their findings may not be fully generalizable, as their population included more cognitive and physically able residents [50, 58, 75], who could be actively involved in the practice of sleep hygiene principles [50] or self-relaxation techniques [58, 75]. Studies using these interventions may demonstrate better outcomes among the growing population in assisted-living facilities, which has similar characteristics.

The overall assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies revealed that the majority of RCTs were at low risk for most types of risk of bias and most non-RCTs met the standard quality criteria. There were several quality concerns, however, for both study types because we chose to include studies that were underpowered, had a high dropout rate, did not include a control/comparison group, and/or did not collect long-term outcomes.

Also, in some cases, it was difficult to identify which component(s) of a multicomponent intervention contributed to the outcome [85]. These complex interventions, as well as single-component interventions, require considerable resident or staff effort, resulting in participant attrition. Treatment adherence is an important aspect of any proposed intervention, indicating its acceptability to both the participant and the staff. Some interventions require equipment that needs to be maintained by staff and may not be readily available. Correct use of an intervention, whether equipment-based or staff-delivered, necessitates staff/provider training. Also, regular supervision is needed to ensure continued accurate execution, and a quality-improvement program is needed to monitor institution-based outcomes. Intervention integrity was not assessed in this review because only a few studies documented any aspect of treatment fidelity.

Conclusions

This systematic review located 54 articles evaluating the effects of 25 different non-pharmacological interventions aimed at improving nighttime sleep in long-term care settings. The analysis of these interventions, applied either in isolation or combination, did not reveal a clear pattern of positive findings. Three interventions had the most promising results: increased daytime light exposure (n = 21), nighttime use of melatonin (n = 6), and acupressure prior to sleep (n = 4).

This review highlights the need for further research to help standardize non-pharmacological interventions to improve sleep in institutionalized settings, including dose and timing of light and melatonin use and site of acupressure, and to determine the optimal combination of interventions. Furthermore, more consistent outcome measurements and identification of sub-groups that would best benefit from certain interventions, along with detailed analyses of cost/benefit ratios and feasibility are needed. In summary, non-pharmacological interventions have the potential to improve sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances in residents of long-term care facilities; however, further research is needed to better standardize such interventions and provide clear implementation guidelines using cost-effective practices.

Abbreviations

- RCT :

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SD :

-

Standard deviation

References

Fung CH, Martin JL, Chung C, Fiorentino L, Mitchell M, Josephson KR, et al. Sleep disturbance among older adults in assisted living facilities. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:485–93.

Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disturbances in nursing homes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:207.

Fung CH, Vitiello MV, Alessi CA, Kuchel GA. AGS/NIA Sleep Conference Planning Committee and Faculty. Report and research agenda of the American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging bedside-to-bench conference on sleep, circadian rhythms, and aging: new avenues for improving brain health, physical health, and functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:238–47.

Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, Cauley JA. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:21–30.

Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA, Schwartz JB. Patterns of chronic co-morbid medical conditions in older residents of US nursing homes: differences between the sexes and across the agespan. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(4):429–36.

Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D. Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:658–66.

Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, Nuti A. Sleep disturbances and dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015;15:65–74.

Saeed Y, Abbott SM. Circadian disruption associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(4):29.

Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Brown LC, Ives TJ, Walsh JF. Inappropriate medication prescribing in residential care/assisted living facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1001–11.

Maust DT, Langa KM, Blow FC. Psychotropic use and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms among patients with dementia in the USA. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:164–74.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46.

Berry SD, Lee Y, Cai S, Dore DD. Non-benzodiazepine sleep medications and hip fractures in nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:754–61.

Saarelainen L, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Sund R, Tiihonen J, et al. Risk of hip fracture in benzodiazepine users with and without Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:87–e15.

Bicket MC, Samus QM, McNabney M, Onyike CU, Mayer LS, Brandt J, et al. The physical environment influences neuropsychiatric symptoms and other outcomes in assisted living residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1044–54.

Cruise PA, Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, Ouslander JG. The nighttime environment and incontinence care practices in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:181–6.

Cabrera E, Sutcliffe C, Verbeek H, Saks K, Soto-Martin M, Meyer G, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions as a best practice strategy in people with dementia living in nursing homes. A systematic review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6:134–50.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;6:e100010.

Capezuti E, Sagha Zadeh R, Woody N, Basara A, Krieger AC. An integrative review of nonpharmacological interventions to improve sleep among adults with advanced serious illness. Palliat Med. 2018.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 4th ed. Maidenhead Berkshire: Open University Press; 2014.

Chen ML, Lin LC, Wu SC, Lin JG. The effectiveness of acupressure in improving the quality of sleep of institutionalized residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M389–94.

Chen KM, Chen MH, Lin MH, Fan JT, Lin HS, Li CH. Effects of yoga on sleep quality and depression in elders in assisted living facilities. J Nurs Res. 2010;18:53–61.

Lee Y, Kim S. Effects of indoor gardening on sleep, agitation, and cognition in dementia patients—a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:485–9.

Lyketsos CG, Lindell Veiel L, Baker A, Steele C. A randomized, controlled trial of bright light therapy for agitated behaviors in dementia patients residing in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(7):520–5.

O’Rourke DJ, Klaasen KS, Sloan JA. Redesigning nighttime care for personal care residents. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27:30–7.

Richards KC, Lambert C, Beck CK, Bliwise DL, Evans WJ, Kalra GK, et al. Strength training, walking, and social activity improve sleep in nursing home and assisted living residents: randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:214–23.

Riemersma-Van Der Lek RF, Swaab DF, Twisk J, Hol EM, Hoogendijk WJ, Van Someren EJ. Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2642–55.

Rondanelli M, Opizzi A, Monteferrario F, Antoniella N, Manni R, Klersy C. The effect of melatonin, magnesium, and zinc on primary insomnia in long-term care facility residents in Italy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:82–90.

Soden K, Vincent K, Craske S, Lucas C, Ashley S. A randomized controlled trial of aromatherapy massage in a hospice setting. Palliat Med. 2004;18:87–92.

Sun JL, Sung MS, Huang MY, Cheng GC, Lin CC. Effectiveness of acupressure for residents of long-term care facilities with insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:798–805.

Wu MC, Sung HC, Lee WL, Smith GD. The effects of light therapy on depression and sleep disruption in older adults in a long-term care facility. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:653–9.

Taboonpong S, Puthsri N, Kong-In W, Saejew A. The effects of Tai Chi on sleep quality, well-being and physical performances among older adults. Thai J Nurs Res. 2010;12:1–13.

Alessi CA, Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Ouslander JG, Al-Samarrai N, Simmons SF, et al. Does physical activity improve sleep in impaired nursing home residents? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1098–102.

Alessi CA, Yoon EJ, Schnelle JF, Al-Samarrai NR, Cruise PA. A randomized trial of a combined physical activity and environmental intervention in nursing home residents: do sleep and agitation improve? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:784–91.

Ancoli-Israel S, Gehrman P, Martin JL, Shochat T, Marler M, Corey-Bloom J, et al. Increased light exposure consolidates sleep and strengthens circadian rhythms in severe Alzheimer's disease patients. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1:22–36.

Ancoli-Israel S, Martin JL, Kripke DF, Marler M, Klauber MR. Effect of light treatment on sleep and circadian rhythms in demented nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:282–9.

Burns A, Allen H, Tomenson B, Duignan D, Byrne J. Bright light therapy for agitation in dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:711–21.

Calkins M, Szmerekovsky JG, Biddle S. Effect of increased time spent outdoors on with dementia residing in nursing homes. J Hous Elderly. 2007;21:211–28.

Connell BR, Sanford JA, Lewis D. Therapeutic effects of an outdoor activity program on nursing home residents with dementia. J Hous Elderly. 2007;21:194–209.

Dowling GA, Hubbard EM, Mastick J, Luxenberg JS, Burr RL, Van Someren EJ. Effect of morning bright light treatment for rest–activity disruption in institutionalized patients with severe Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17:221–36.

Matthews EA, Farrell GA, Blackmore AM. Effects of an environmental manipulation emphasizing client-centered care on agitation and sleep in dementia sufferers in a nursing home. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:439–47.

Richards KC, Sullivan SC, Phillips RL, Beck CK, Overton-McCoy AL. The effect of individualized activities on the sleep of nursing home residents who are cognitively impaired: a pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27:30–7.

Richards KC, Beck C, O'Sullivan PS, Shue VM. Effect of individualized social activity on sleep in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1510–7.

Schnelle JF, Cruise PA, Alessi CA, Al-Samarrai N, Ouslander JG. Individualizing nighttime incontinence care in nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 1998;47:197–204.

Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Al-Samarrai NR, Fricker RD Jr, Ouslander JG. The nursing home at night: effects of an intervention on noise, light and sleep. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:430–8.

Thodberg K, Sørensen LU, Christensen JW, Poulsen PH, Houbak B, Damgaard V, et al. Therapeutic effects of dog visits in nursing homes for the elderly. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16:289–97.

Valtonen M, Niskanen L, Kangas AP, Koskinen T. Effect of melatonin-rich night-time milk on sleep and activity in elderly institutionalized subjects. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59:217–21.

Van Someren EJ, Scherder EJ, Swaab DF. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) improves circadian rhythm disturbances in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12(2):114–8.

Akyar I, Akdemir N. The effect of light therapy on the sleep quality of the elderly: an intervention study. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2013;31:31.

El Kady HM, Ibrahim HK, Mohamed SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for institutionalized elders complaining of sleep disturbance in Alexandria, Egypt. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:1173–80.

Kuck J, Pantke M, Flick U. Effects of social activation and physical mobilization on sleep in nursing home residents. Geriatr Nurs. 2014;35:455–61.

Martin JL, Marler MR, Harker JO, Josephson KR, Alessi CA. A multicomponent nonpharmacological intervention improves activity rhythms among nursing home residents with disrupted sleep/wake patterns. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:67–72.

Figueiro MG, Plitnick BA, Lok A, Jones GE, Higgens P, Hornick TR, et al. Tailored lighting intervention improves measures of sleep, depression, and agitation in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia living in long-term care facilities. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1527–37.

Ouslander JG, Connell BR, Bliwise DL, Endeshaw Y, Griffiths P, Schnelle JF. A nonpharmacological intervention to improve sleep in nursing home patients: results of a controlled clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:38–47.

Lorenz RA, Gooneratne N, Cole CS, Kleban MH, Kalra GK, Richards KC. Exercise and social activity improve everyday function in long-term care residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:468–76.

Ancuelle V, Zamudio R, Mendiola A, Guillen D, Ortiz PJ, Tello T, et al. Effects of an adapted mattress in musculoskeletal pain and sleep quality in institutionalized elders. Sleep Sci. 2015;8:115–20.

Chen KM, Huang HT, Cheng YY, Li CH, Chang YH. Sleep quality and depression of nursing home older adults in wheelchairs after exercises. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63:357–65.

Örsal Ö, Alparslan GB, Özkaraman A, Sönmez N. The effect of relaxation exercises on quality of sleep among the elderly: holistic nursing practice review copy. Holist Nurs Pract. 2014;28:265–74.

Reza H, Kian N, Pouresmail Z, Masood K, Sadat Seyed Bagher M, Cheraghi MA. The effect of acupressure on quality of sleep in Iranian elderly nursing home residents. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:81–5.

Simoncini M, Gatt A, Quirico PE, Balla S, Capellero B, Obialero R, et al. Acupressure in insomnia and other sleep disorders in elderly institutionalized patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:37–42.

Fetveit A, Skjerve A, Bjorvatn B. Bright light treatment improves sleep in institutionalised elderly—an open trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:520–6.

Braun C, Layton J, Braun J. Therapeutic touch improves residents' sleep. J Am Health Care Assoc. 1986;12:48.

Castor D, Woods D, Pigott K. Effect of sunlight on sleep patterns of the elderly. J Am Acad Physician Assist. 1991;4:321–6.

Fetveit A, Bjorvatn B. The effects of bright-light therapy on actigraphical measured sleep last for several weeks post-treatment. A study in a nursing home population. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:153–8.

Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, Cynthia Kim E, Harker JO, Josephson KR. Randomized, controlled trial of a nonpharmacological intervention to improve abnormal sleep/wake patterns in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:803–10.

Dowling GA, Burr RL, Van Someren EJ, Em H, Luxenberg JS, Mastick J, et al. Melatonin and bright-light treatment for rest–activity disruption in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:239–46.

Eggermont LH, Blankevoort CG, Scherder EJ. Walking and night-time restlessness in mild-to-moderate dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2010;9:746–9.

Gehrman PR, Connor DJ, Martin JL, Shochat T, Corey-Bloom J, Ancoli-Israel S. Melatonin fails to improve sleep or agitation in double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of institutionalized patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:166–9.

Harris M, Richards KC, Grando VT. The effects of slow-stroke back massage on minutes of nighttime sleep in persons with dementia and sleep disturbances in the nursing home: a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30:255–63.

Ito T, Yamadera H, Ito R, Suzuki H, Asayama K, Endo S. Effects of vitamin B12 on bright light on cognitive and sleep–wake rhythm in Alzheimer-type dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:281–2.

Koyama E, Matsubara H, Nakano T. Bright light treatment for sleep–wake disturbances in aged individuals with dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53:227–9.

Gammack JK, Burke JM. Natural light exposure improves subjective sleep quality in nursing home residents. JAMDA. 2009;10(6):440–1.

Kim HJ, Lee Y, Sohng KY. The effects of footbath on sleep among the older adults in nursing home: a quasi-experimental study. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:40–6.

Nelson R, Coyle C. Effects of a bedtime massage on relaxation in nursing home residents with sleep disorders. Act Adapt Aging. 2010;34(3):216–31.

Anderiesen H, Scherder EJ, Goossens RH, Sonneveld MH. A systematic review–physical activity in dementia: the influence of the nursing home environment. Appl Ergon. 2014;45:1678–86.

Resnick B, Galik E, Boltz M. Function focused care approaches: literature review of progress and future possibilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:313–8.

Van Maanen A, Meijer AM, van der Heijden KB, Oort FJ. The effects of light therapy on sleep problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:52–62.

Chiu HL, Chan PT, Chu H, Hsiao SS, Liu D, Lin CH, et al. Effectiveness of light therapy in cognitively impaired persons: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2227–34.

Ploeg ES, O'Connor DW. Methodological challenges in studies of bright light therapy to treat sleep disorders in nursing home residents with dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:777–84.

Lack LC, Gradisar M, Van Someren EJ, Wright HR, Lushington K. The relationship between insomnia and body temperatures. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:307–17.

Burns D, Hyde P, Killett A, Poland F, Gray R. Participatory organizational research: examining voice in the co-production of knowledge. Br J Manag. 2014;25:133–44.

Waits A, Tang YR, Cheng HM, Chen-Jei T, Chien L-Y. Acupressure effect on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.12.004; [Epub ahead of print]

Xu J, Wang LL, Dammer EB, Li CB, Xu G, Chen SD, et al. Melatonin for sleep disorders and cognition in dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30:439–47.

Wang YY, Zheng W, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Wei W, Xiang YT. Meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of melatonin in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;32:50–7.

Petticrew M, Anderson L, Elder R, Grimshaw J, Hopkins D, Hahn R, et al. Complex interventions and their implications for systematic reviews: a pragmatic approach. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1211–6.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Paul Eshelman, MFA, and Jennifer Tiffany, RN, MRP, PhD, of Cornell University for their substantive input to the overall design of the grants supporting this work. We acknowledge the assistance of Cynthia Lien, MD; Eugenia L. Siegler, MD; and Dale Johnson for input on research scope. Special thanks to Hessam Sadatsafavi for grant submission management, Kimia Erfani for assistance with the PRISMA flow chart, and Melissa Kuhnell for manuscript preparation.

Funding

This study was supported by the New York State Department of Food and Agriculture’s Smith Lever Fund, the Building Faculty Connections Program Fund of Cornell University’s College of Human Ecology, and the Professional Staff Congress at CUNY. These funders had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author took an active role in the literature data collection, evaluation, and synthesis. RSZ, ACK and EC worked closely with KP to develop the search strategies. After KP located articles, all other co-authors reviewed the studies based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Research assistants AB and NZJ developed the tables under our supervision and we all contributed to the reporting of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Detailed search strategies. Detailed search strategies for each database: Cochrane Library (Wiley), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus. (PDF 89 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Individual study results for Cochrane Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Trials [89] (n = 30). Provides details (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting) for individual studies. (DOC 75 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Individual studies’ results for the quantitative studies and critical appraisal checklist (n = 24). Provides details for each individual study using the nineteen criteria from the Summary Quantitative Studies and Critical Appraisal Checklist. (DOC 109 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Capezuti, E., Sagha Zadeh, R., Pain, K. et al. A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions to improve nighttime sleep among residents of long-term care settings. BMC Geriatr 18, 143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0794-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0794-3