Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the short-term outcomes and prognosis of elderly and very elderly colorectal cancer (CRC) patients after primary CRC surgery using propensity score matching (PSM).

Methods

This study retrospectively collected the medical records of CRC patients ≥ 65 years old undergoing primary CRC surgery from Jan 2011 to Jan 2020. Short-term outcomes, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were compared between very elderly CRC patients (≥ 80 years old) and elderly CRC patients (65–79 years old).

Results

A total of 2084 patients were enrolled for analysis. After PSM, 331 very elderly patients were matched to 331 elderly patients. In terms of short-term outcomes, the very elderly patients had longer postoperative hospital stays (p = 0.007) after PSM. In terms of OS, it was found that age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.878, 95% CI 1.488–2.371), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.865, 95% CI 1.603–2.170), overall complications (p < 0.01, HR = 1.514, 95% CI 1.224–1.872) and major complications (p = 0.001, HR = 2.012, 95% CI 1.319–3.069) were independent prognostic factors. For DFS, age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.816, 95% CI 1.579–2.088), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.816, 95% CI 1.579–2.088), overall complications (p = 0.002, HR = 1.379, 95% CI 1.128–1.685) and major complications (p = 0.002, HR = 1.902, 95% CI 1.259–2.874) were found to be independent prognostic factors. Moreover, elderly patients had a better OS and DFS than very elderly patients.

Conclusion

Very elderly patients had a poorer prognosis than elderly patients after primary CRC surgery. Surgeons should be cautious when treating very elderly CRC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most commonly occurring cancer and the third-leading cause of cancer-related death globally [1]. The number of newly diagnosed cases of CRC reached 2 million, and cancer-related deaths were expected to reach 1 million in 2018 [1]. Radical CRC surgery is the primary course of treatment in resectable cases [2]. Predictive risk factors for the occurrence of CRC include age, alcohol consumption, a high-fat diet and physical inactivity [3,4,5].

It was reported that 16% of the world population would be ≥ 65 years of age by 2050 due to the aging of society, with an expected increase in elderly patients with CRC [6]. More elderly patients underwent CRC surgery and received chemoradiotherapy after surgery because of the updated techniques with higher safety and effectiveness [7]. However, compared with nonelderly patients, elderly patients usually had more comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes (T2DM), cardiopulmonary insufficiency or chronic renal insufficiency.

In previous studies, age was an independent risk factor for in-hospital complications and mortality after CRC surgery [8,9,10]. Patients ≥ 80 years of age can potentially suffer from severe complications and mortality [11]. However, no previous studies have reported comparisons between elderly and very elderly CRC patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the short-term outcomes and prognosis of elderly and very elderly CRC patients after primary CRC surgery.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively collected the medical records of CRC patients undergoing primary CRC surgery from Jan 2011 to Jan 2020 in a clinical center. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the local hospital (2021-517).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

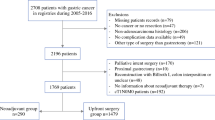

Patients who underwent primary CRC surgery and were diagnosed pathologically with CRC after surgery were initially included in this study (n = 5473). The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1, pathologically diagnosed stage IV CRC (n = 875); 2, an age of < 65 years (n = 2166); 3, incomplete medical records (n = 323); and 4, non-R0 resection (n = 25). Therefore, a total of 2084 patients were enrolled in the final analysis.

Peri-operative management and surveillance

Radical colorectal resection and lymph node dissection were routinely performed in all patients according to the AJCC 8th Edition [12].

All patients who underwent CRC surgery were advised to receive regular laboratory evaluation and appropriate exercise for postoperative recovery. Follow-up was recommended every three months after CRC surgery for the first three years and every six months for the next two years. The follow-up included carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and colonoscopy.

Definitions

The patients were divided into the following two groups: elderly patients were defined from 65 to 79 years old, and very elderly patients were defined as ≥ 80 years of age. The tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage was documented in accordance with the AJCC 8th Edition [12]. R0 resection was defined as a negative margin on pathological examination. Postoperative complications were graded by the Clavien-Dindo classification, [13] and the major complications were defined as ≥ grade III, which required surgery, endoscopy or radiological intervention. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from CRC surgery to death or last follow-up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from CRC surgery to recurrence, metastasis, death or last follow-up.

Data collection

The baseline information and short-term outcomes were collected from electronic medical records for analysis. The baseline information included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), T2DM, smoking, drinking, hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), surgical methods, tumor location and tumor stage. The short-term outcomes included operation time, blood loss, retrieved lymph nodes, postoperative hospital stay, overall complications and major complications. The follow-up results were collected from the outpatient department records or through telephone interviews.

Propensity score matching (PSM)

To minimize the selection bias in baseline characteristics between the two groups, [14] very elderly patients were matched to elderly patients using the PSM method in this study. Nearest neighbor matching was performed without replacement at a 1:1 ratio, and a caliper width with a 0.01 standard deviation (SD) was specified.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD, and an independent-sample t test was used to compare the difference between the elderly and very elderly groups. Categorical variables are expressed as n (%), and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify predictors of overall complications. Predictive factors for OS and DFS were identified through Cox regression analyses. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare OS and DFS between the elderly and very elderly groups. Furthermore, multivariate linear regression was conducted between the length of postoperative hospital stay and the patient’s clinical characteristics. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 22.0) statistical software. A result was considered statistically significant when the bilateral p value was < 0.05.

Results

Patients

A total of 5473 patients were identified in a single clinical database. After adjusting for the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 2084 patients enrolled for analysis, including 331 very elderly patients and 1753 elderly patients. Then, after using a 1:1 ratio for PSM, 331 very elderly patients were matched to 331 elderly patients. The flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline characteristics

Very elderly patients and elderly patients were compared in terms of the baseline characteristics. Elderly patients had a younger age (p < 0.01), a higher BMI (p = 0.017), a higher proportion of smoking (p < 0.01), a higher proportion of drinking (p < 0.01), a lower proportion of hypertension (p < 0.01) and a lower proportion of CHD (p < 0.01). Moreover, tumor location (p = 0.001) and tumor stage (p = 0.035) were significantly different. No significant difference was found after PSM except for age (Table 1).

Short-term outcomes

Short-term outcomes were compared between the two groups, including operation time, blood loss, retrieved lymph nodes, postoperative hospital stay, overall complications and major complications. Very elderly patients had longer postoperative hospital stays (p = 0.015) and higher overall complications (p < 0.01) than elderly patients. After PSM, very elderly patients also had longer postoperative hospital stays (p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of OS

The median follow-up time was 37 (1–114) months. To identify predictive risk factors for OS, we carried out the univariate and multivariate analyses. In univariate analysis, major complications (p < 0.01, HR = 2.173, 95% CI 1.460–3.235), overall complications (p < 0.01, HR = 1.638, 95% CI 1.340–2.002), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.826, 95% CI 1.571–2.123), tumor location (p = 0.020, HR = 1.262, 95% CI 1.037–1.536) and age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.967, 95% CI 1.561–2.478) were considered as predictors. Furthermore, in multivariate analysis, we found that four independent prognostic factors for OS, which were as follows: age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.878, 95% CI 1.488–2.371), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.865, 95% CI 1.603–2.170), overall complications (p < 0.01, HR = 1.514, 95% CI 1.224–1.872) and major complications (p = 0.001, HR = 2.012, 95% CI 1.319–3.069) (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of DFS

In terms of DFS, we found four predictive risk factors in univariate analysis, including major complications (p = 0.001, HR = 1.992, 95% CI 1.350–2.939), overall complications (p < 0.01, HR = 1.500, 95% CI 1.240–1.813), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.788, 95% CI 1.554–2.056) and age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.826, 95% CI 1.467–2.274). In multivariate analysis, four independent prognostic factors were found for DFS, which included as follows: age (p < 0.01, HR = 1.816, 95% CI 1.579–2.088), tumor stage (p < 0.01, HR = 1.816, 95% CI = 1.579–2.088), overall complications (p = 0.002, HR = 1.379, 95% CI 1.128–1.685), and major complications (p = 0.002, HR = 1.902, 95% CI 1.259–2.874) (Table 4).

Prognosis before and after PSM

Kaplan–Meier curves were generated before and after PSM for OS and DFS, respectively. Before PSM, elderly patients had better OS (p < 0.01) and better DFS (p < 0.01) than very elderly patients (Fig. 2a, b). Furthermore, after PSM, elderly patients had better OS (p = 0.001) and better DFS (p = 0.001) than very elderly patients (Fig. 2c, d).

Multivariate analysis of the very elderly patients

To explore the predictive factors of overall complications and postoperative hospital stay, we conducted multivariate analysis in very elderly patients. Regarding overall complications, open CRC surgery (p = 0.002, OR = 2.552, 95% CI = 1.410–4.618) was an independent predictor (Table 5). In terms of postoperative hospital stay, operation time (β = 0.114, p = 0.046) was significantly correlated with the postoperative hospital stay (Table 6).

Discussion

A total of 2084 patients were included in this study. To balance the difference in baseline characteristics, 331 very elderly patients were matched to 331 elderly patients using the PSM method. In terms of short-term outcomes, very elderly patients had longer postoperative hospital stays than elderly patients. Elderly patients had better OS and DFS than very elderly patients. In multivariate analysis, it was found that age, tumor stage, overall complications and major complications were independent prognostic factors for OS and DFS.

It was reported that age was associated with prognosis in terms of treating malignant tumors [15, 16]. In general, elderly patients were more likely to have cardio-cerebrovascular and pulmonary comorbidities, which affected the postoperative recovery and the sequential postoperative chemoradiotherapy [17, 18]. Utsumi M et al. [19] compared the surgical outcomes between the elderly group (≥ 80 years old) and the nonelderly group (< 80 years old) using the PSM method and found that age was not a predictor of postoperative complications after CRC surgery; however, the conclusion was unconvincing due to limited data. Thus, we further investigated whether age (focused on aged CRC patients) had an effect on short-term outcomes or prognosis after CRC surgery using the PSM method.

PSM was a relatively optimal method to minimize the bias of baseline information, and after matching, no significant difference was found in the elderly and very elderly groups. The cutoff age varied when defining the elderly and the very elderly groups [9, 10]. In this study, we chose 80 years of age as the cutoff age for analysis, which was consistent with the majority of previous studies [19,20,21,22].

As previous studies reported, postoperative complications were associated with longer postoperative hospital stays, heavier financial burdens, lower quality of life and worse prognoses [23, 24]. Odermatt M et al. [25] reported that elderly CRC patients experienced more major complications after surgery, including cardio-cerebrovascular accidents, pulmonary infections, deep venous thrombosis and anastomotic leakage. Furthermore, it was reported that age was an independent risk factor for anastomotic leakage [26]. However, we analyzed the current data and found no significant difference in postoperative complications between elderly and very elderly patients. The reason might be that the baseline information was matched between the two groups. In addition, very elderly patients had longer postoperative hospital stays than elderly patients in this study. Potential malnutrition and poor healing ability might contribute to this result. Furthermore, for very elderly patients, open CRC surgery was an independent predictor of overall complications, and operation time was significantly correlated with the postoperative hospital stay. Therefore, laparoscopic surgery with a shorter operation time is recommended for very elderly CRC patients [27, 28].

Most studies reported that CRC patients (age ≥ 80 years old) had higher mortality after CRC surgery [29, 30]. Chan et al. [31] reported that 36.8% of elderly patients suffered from pneumonia and respiratory failure, the leading cause of mortality after CRC surgery. Hinoi et al. [20] reported that the 3-year OS rate in elderly (age ≥ 80 years old) colon cancer patients with stage I-III disease was 85.5%, and the 3-year OS rate was 78.6% in elderly (age ≥ 80 years old) rectal cancer patients. In this study, we found that elderly patients had better OS than very elderly patients. Furthermore, tumor stage and complications were predictors of OS. Aging leads to a progressive decline in the functional reserve of multiple organ systems; [32] therefore, very elderly patients have worse OS.

In fact, the treatment for elderly CRC patients is based on the assessment of physiological age, patient life expectancy, and tolerance to treatment [33]. Very elderly patients who commonly have concurrent impaired liver or renal function might be undertreated for malignancy, which leads to the rapid recurrence of tumors and worse DFS [32]. In our study, very elderly patients had worse DFS than elderly patients, which could be explained by the undertreatment of very elderly patients.

Interestingly, the process of aging is highly individualized, and discrepancies between physiological and chronological age are a challenge for surgeons [25, 35]. Therefore, the surgical strategy and postoperative chemotherapy regimen should be conducted individually.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to compare the short-term outcomes and prognosis between very elderly patients and elderly patients using the PSM method. However, there were some limitations in this study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, which might cause bias. Second, the median follow-up time was relatively short. Thus, multicenter prospective randomized controlled trials with comprehensive perioperative information should be performed in the future.

In conclusion, very elderly patients had a poorer prognosis than elderly patients after primary CRC surgery. Surgeons should be cautious about aged CRC patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [The database from our clinical center were relatively private] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- TNM:

-

Tumor node metastasis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

Kekelidze M, D’Errico L, Pansini M, et al. Colorectal cancer: current imaging methods and future perspectives for the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic response evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(46):8502–14. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8502.

Marventano S, Forjaz M, Grosso G, et al. Health related quality of life in colorectal cancer patients: state of the art. BMC Surg. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S15.

Schlesinger S, Walter J, Hampe J, et al. Lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(1):99–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0313-y.

Neuman HB, Weiss JM, Leverson G, et al. Predictors of short-term postoperative survival after elective colectomy in colon cancer patients ≥ 80 years of age. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1427–35. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2721-8.

Søreide K, Wijnhoven BP. Surgery for an ageing population. Br J Surg. 2016;103(2):e7-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10071.

Ommundsen N, Wyller TB, Nesbakken A, et al. Preoperative geriatric assessment and tailored interventions in frail older patients with colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20(1):16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13785.

Chong RC, Ong MW, Tan KY. Managing elderly with colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(6):1266–73. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2019.09.04.

Day LW, Velayos F. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in the elderly: updates and controversies. Gut Liver. 2015;9(2):143–51. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14302.

Angenete E. Reducing morbidity and mortality in the elderly population with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(4):362–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15029.

Itatani Y, Kawada K, Sakai Y. Treatment of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018;11(2018):2176056. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2176056.

Weiser MR. AJCC 8th edition: colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1454–5. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6462-1.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3697.

Wang D, Zhang J, Bai Z, et al. Associations of postoperative complications assessed by Clavien-Dindo classification and comprehensive complication index with long-term overall survival in elderly patients after radical CRC resection. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;13(15):1939–49. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S271969.

Wakahara T, Ueno N, Maeda T, et al. Impact of gastric cancer surgery in elderly patients. Oncology. 2018;94(2):79–84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481404.

Dekker JW, van den Broek CB, Bastiaannet E, et al. Importance of the first postoperative year in the prognosis of elderly colorectal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1533–9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1671-x.

Zawadzki M, Krzystek-Korpacka M, Rząca M, et al. Colorectal surgery in elderly population. Pol Przegl Chir. 2018;90(4):29–34. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0011.8179.

Utsumi M, Matsuda T, Yamashita K, et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic surgery for elderly patients with colorectal cancer aged over 80 years: a propensity score matching analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(11):2519–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-03973-z.

Hinoi T, Kawaguchi Y, Hattori M, et al. Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a multicenter matched case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):2040–50. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4172-x.

Wong JU, Tai FC, Huang CC. An examination of surgical and survival outcomes in the elderly (65–79 years of age) and the very elderly (≥ 80 years of age) who received surgery for gastric cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(2):229–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1520083.

Zhang H, Hu H, Huang R, et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional laparoscopic-assisted resection for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a propensity-score matching study. Updates Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01143-y.

de la Plaza LR, Hidalgo Vega Á, Latorre Fragua RA, et al. The Cost of postoperative complications and economic validation of the comprehensive complication index: prospective study. Ann Surg. 2021;273(1):112–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003308.

Bai Z, Wang J, Wang T, et al. Clinicopathologic parameters associated with postoperative complications and risk factors for tumor recurrence and mortality after tumor resection of patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(2):176–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-017-1708-0.

Odermatt M, Miskovic D, Flashman K, et al. Major postoperative complications following elective resection for colorectal cancer decrease long-term survival but not the time to recurrence. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(2):141–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12757.

Bakker IS, Grossmann I, Henneman D, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage and leak-related mortality after colonic cancer surgery in a nationwide audit. Br J Surg. 2014;101(4):424–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9395.

Devoto L, Celentano V, Cohen R, et al. Colorectal cancer surgery in the very elderly patient: a systematic review of laparoscopic versus open colorectal resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(9):1237–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2848-y.

Shen L, Meng K, Wang Y, et al. The clinical features, management, and survival of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(1):89–99. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo-21-63.

Taylor JC, Iversen LH, Burke D, et al. YCR BCIP Study Group Influence of age on surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer in Denmark and Yorkshire, England. Colorectal Dis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15910.

Papamichael D, Audisio RA, Glimelius B, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(3):463–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu253.

Chan TY, Foo CC, Law WL, et al. Outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery in the nonagenarians: 20-year result from a tertiary center. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0623-4.

Millan M, Merino S, Caro A, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(10):204–20. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v7.i10.204.

Vacante M, Cristaldi E, Basile F, et al. Surgical approach and geriatric evaluation for elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Updates Surg. 2019;71(3):411–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00650-3.

Bouassida M, Charrada H, Chtourou MF, et al. Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: how could we improve early outcomes? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(5):PC04-8. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/12213.5973.

Kowdley GC, Merchant N, Richardson JP, et al. Cancer surgery in the elderly. SciWorldJ. 2012;2012: 303852. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/303852.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the authors whose publications are referred in our article, and we thank Xun Lei for the substantial work in the statistical methods.

Funding

This study was supported by Chongqing key diseases Research and Application Demonstration Program (Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Treatment Technology Research and Application Demonstration [No. 2019ZX003]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to data collection and analysis, drafting or revising the manuscript, have agreed on the journal to which the manuscript will be submitted, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, 2021-517), and all patients signed informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki as well.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, YX., Liu, XY., Kang, B. et al. Comparison of surgical and oncologic outcomes in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years old) and elderly (65–79 years old) colorectal cancer patients: a propensity score matching. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 205 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02277-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02277-y