Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is growing globally. The practice of health professionals when prescribing antibiotics in primary health care settings significantly impacts antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic prescription is a complex process influenced by various internal and external factors. This systematic review aims to summarize the available evidence regarding factors contributing to the variation in antibiotic prescribing among physicians in primary healthcare settings.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted based on PRISMA guidelines. We included qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies that examined factors influencing prescription practice and variability among primary healthcare physicians. We excluded editorials, opinions, systematic reviews and studies published in languages other than English. We searched studies from electronic databases: PubMed, ProQuest Health and Medicine, Web Science, and Scopus. The quality of the included studies was appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Version 2018). Narrative synthesis was employed to synthesize the result and incorporate quantitative studies.

Results

Of the 1816 identified studies, 49 studies spanning 2000–2023 were eligible for review. The factors influencing antibiotic prescription practice and variability were grouped into physician-related, patient-related, and healthcare system-related factors. Clinical guidelines, previous patient experience, physician experience, colleagues’ prescribing practice, pharmaceutical pressure, time pressure, and financial considerations were found to be influencing factors of antibiotic prescribing practice. In addition, individual practice patterns, practice volume, and relationship with patients were also other factors for the variability of antibiotic prescription, especially for intra-physician prescription variability.

Conclusion

Antibiotic prescription practice in primary health care is a complex practice, influenced by a combination of different factors and this may account for the variation. To address the factors that influence the variability of antibiotic prescription (intra- and inter-physician), interventions should aim to reduce diagnostic uncertainty and provide continuous medical education and training to promote patient-centred care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A pandemic of disease with antibiotic resistance is spreading throughout the planet [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 80% of antibiotics are used in primary health care [2]. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat bacterial infections, especially acute respiratory tract infections, raises the risk of antibiotic resistance [3]. The practice of health professionals when prescribing antibiotics in primary healthcare settings significantly contributed to antibiotic resistance [4, 5]. The prescribing of antibiotics can vary significantly from one medical practice to another and evidence highlights that primary care physicians in different locations have variable rates for the prescription of antibiotics [6,7,8,9,10].

Studies reported that variation in patient characteristics, physician experience, patient expectation, power distance and the practice environment which may affect how often a physician prescribes antibiotics [9, 11]. The observed variability in antibiotic prescribing, according to Schwartz, et al. [12], may not be only explained by clinical or sociodemographic variations among the patient population. Instead, it may be related to each physician's unique prescribing patterns and patient preference. Furthermore, variance in the prescription of antibiotics by primary healthcare physicians in different nations has been observed; however, it remains unclear which factors play important roles and how different factors interact with prescribing variation [13, 14].

Published studies overlooked physicians’ beliefs on antibiotic resistance and the unforeseen factors contribute to prescription variability [15, 16]. Recent studies by Durand, et al. [17], Manne, et al. [14], and Queder, et al. [18] investigated factors influencing physician’s antibiotic prescribing practice in specific locations. These findings indicated that physicians’ antibiotic prescribing is influenced by contextual factors at the individual practice and systemic levels. However, it is 128important to note that these findings may not be generalizable to healthcare systems in other countries outside the study area. To support optimal prescribing interventions, understanding the underlying cause of variation is crucial [19, 20]. Due to knowledge gap in this area, a systematic review is required to synthesize the existing qualitative and quantitative research on primary health care physicians’ experience with prescribing antibiotics. Therefore, this review aims to identify the potential drivers that influence prescription practice and variability in antibiotic prescribing among primary healthcare physicians.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [21] and followed a predefined protocol. The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) CRD42023438530.

Eligibility criteria

The reasons for variation in antibiotic prescribing among physicians in primary healthcare settings were the main focus of the review. Studies that focused on factors that influence prescribing practices and variations in antibiotic prescriptions, published in English-language peer-reviewed journals with primary healthcare physicians as participants were included. The studies were included without restriction in study methods (qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies). Studies that did report factors affecting antibiotic prescription practice and variation, as well as editorials, study protocols, systematic reviews, and commentary pieces, were excluded. To address the current issues influencing antibiotic prescription practices, we included studies from 2000 onwards.

Information source and search strategy

To identify relevant studies, we conducted a comprehensive search using electronic databases: PubMed, ProQuest Health and Medicine, Web of Science, and Scopus. A combination of relevant keywords such as "antibiotics," "prescribing," "physicians," "primary health care," and "factors” were used in the search query. A 'search strategy using 'or' rather than 'and' was employed to ensure a broad search that included all relevant articles related to prescribing practice. Additionally, the Google Scholar search engine and reference lists from included articles were utilized to retrieve further relevant studies that may have been missed through the database searching process particularly to ensure that qualitative studies were not overlook. The database and search terms were finalized in consultation with a health research librarian. The search was conducted from inception to July 12, 2023. For the full search string, see Supplement file 1.

Study selection process

All retrieved studies were imported into EndNote 20, and duplicates were removed. The selection process was carried out independently by the first author and three co-authors (MSI, JH, and SC). This process involved the review of titles and abstracts, followed by a full -text screening. Any disagreements were handled through discussion.

Data extraction and data items

A standardized data extraction form was developed to collect relevant information from the included studies. Data extraction of included studies was performed by the first author and the other co-authors independently. We read each article (the entire manuscript) carefully and extracted the identified data elements into our collection format. Study design, country, sample size, study objectives, study population, setting, data collection methods, data analysis, study approach, major findings (i.e. factors influencing practice and variation), and recommended interventions were extracted. Intervention is not our primary objective but during analysis of the data we extracted information about possible interventions for identified factors.

Quality assessments

The risk of bias assessment for this review was conducted using recognized tools such as the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (version 2018). This tool is used to appraise methodological quality for different categories of studies, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies [22]. Each included study was independently assessed by four reviewers, and any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved through discussion with other reviewers.

Data synthesis

Following qualitative data extraction, the first author and co-authors independently identified the factors influencing antibiotic prescription practice and variation. We identified different factors from included studies and categorized these factors into three main themes: physicians related factors, patients related factors, and health system related factors, based on the framework predefined by a previous study [23]. The quantitative data were qualitatively described and integrated with qualitative data [24]. Any disagreement with authors were resolved through interactive discussion. Narrative synthesis was used to synthesis quantitative studies, the general characteristic and recommended intervention from included studies. When appropriate, numerical findings were also included in the results of the review.

Results

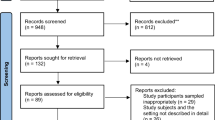

A total of 1816 studies were initially identified. Of these 1816, 1716 studies were obtained from four electronic databases: PubMed (376), Scopus (645), Web of Science (n = 398) and ProQuest Health and Medicine (n = 297). One hundred studies were retrieved from Google Scholar and reference lists of the included studies. After screening titles and abstracts, 120 full-texts articles were assessed against inclusion criteria. Finally, 49 articles were included in the final analysis (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

From the included studies, a total of 24 studies were conducted in European countries, four studies were conducted in Australia, and four were conducted in the USA. Additionally, three studies were carried out in China and Singapore each, with two studies each conducted in Iran, India, and Canada and one each in Cameroon, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Myanmar. One study was carried out concomitantly in Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay (Table 1). From the included studies, thirty used quantitative methods, fifteen used qualitative methods and four employed mixed methods (Table 1). Regarding study design, of the 49 included studies, 47 were observational and 2 were randomized control trials. Regarding data analysis, the qualitative studies used different methods, such as grounded theory (n = 5) and thematic analysis (n = 10). The included mixed method studies used various methods: descriptive and changing point analysis (n = 1), framework analysis and descriptive analysis (n = 1), grounded theory and descriptive (n = 1), and narrative analysis and descriptive (n = 1) analysis.

Quality of studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the MMAT [22]. Of the total studies, twenty-one were five stars (qualified for each of the five criteria), twenty-three were four stars, and the remaining five were three stars (see Table 1). More detailed information regarding the rating of studies is available in Supplementary 2. The majority of studies that used descriptive cross-sectional methodologies applied sampling techniques that were pertinent to the study’s research question. In two mixed methods studies [47, 48], the divergences and inconsistencies between qualitative and qualitative results, along with the outcome of their integration, were not appropriately addressed.

Synthesis of results

We have identified various factors from the included studies that influence antibiotic prescribing practices and contributed to the variation in prescribing (as shown Table 2). As explained in the data synthesis section above, we categorized the factors into three main categories: patient-related factors (knowledge, preference, expectations, culture, economic status, and previous experience), physician-related factors (expertise, knowledge, specific prescription patterns, time constraints, and communication with patients), and health system-related factors (financial incentives, guidelines, policies, and regulations).

Factors influencing antibiotics prescribing practice

Factors influencing prescribing practice include patient-related factors, health system-related factors, and health system related factors.

Patient related factors

Some of the included studies mentioned that the practitioner’s perception of patients influences the antibiotic prescribing practise of physicians [6, 31, 36,37,38, 43, 58, 69, 70]. A study conducted in China reported that patients often had an expectation of receiving antibiotics when they visited healthcare providers, and a perception of this expectation pressures physicians to prescribe [47]. Another study [27] noted that physicians frequently overprescribe antibiotics due to patient expectations and preferences. The expectation and preference of patients who have previously received antibiotics have an effect on the decision of physicians [12, 32, 34, 42, 52].

Reynolds and McKee [47] noted that the economic status of patients affects both the actual and perceived need for antibiotics. Another study also reported that patients do not want to waste money on another prescription; instead, they use their previous prescription to purchase drugs from private or public pharmacy [28, 40]. Similarly, a study focused on prescribing patterns and factors associated with antibiotic prescription in primary healthcare facilities reported that patients with lower financial capacity exerted less pressure on physicians to prescribe antibiotics [54]. In contrast, two studies reported that patients with low income, individual unemployment status and high uncertainty avoidance (minimize risk and unpredictability) are likely to result in patient demand for physician prescription of antibiotics [29, 31] (as shown Table 2).

Patient social characteristics such as education, health literacy levels, and occupation have potentially impacted the perceived need for prescribing antibiotics [25, 27, 50]. Cultural views on health and illness, attitudes about health, and causes of diseases are other patient characteristics that influence antibiotic use. A study conducted in the UK reported that patients seeking immediate relief, cultural beliefs and their previous experience with specific drugs contributed to variability in the prescribing practice of physicians [46]. Another study conducted in India reported that patients who engage in self-diagnosis and self-medication requested specific antibiotics compared with patients who have no knowledge about antibiotics [29]. In addition, the study also found that the patient’s relationship with physicians and the deliberate exaggeration or misinformation of symptoms affect the prescription of antibiotics [38, 51].

Physicians-related factors

Studies show that physicians who actively refresh their expertise through continuing medical training, workshops, seminars and journals, are less likely to prescribe antibiotics [35, 65, 66]. Another important factor constantly reported through the study is time pressures [27, 30, 65, 67]. Two additional studies also reported that diagnostic uncertainty combined with time constraints influenced physicians’ antibiotic prescription practice [8, 39]. A study conducted in the UK reported that time pressure, especially the limited time available for consultation, has an impact on increased antibiotic prescription in primary health care [53]. Chem, et al. [54] reported that complacency, fear, and insufficient knowledge were other factors that influenced the prescribing of antibiotics by physicians. Kumar, et al. [44] and Karimi, et al. [63] stated that knowledge, skills and insights acquired through interaction with patients and medical cases were associated with physicians’ prescription practices and decisions to prescribe antibiotics.

On the other hand, physicians who only practice outpatient medicine are more likely to prescribe antibiotics than in patients [36, 54, 68]. Many physicians did not think that antibiotic prescribing in primary care was responsible for the growth of antibiotic resistance or that their individual prescribing could make any difference in light of other issues, such as hospital prescribing [45, 49, 52]. The included studies show that engagement with antibiotic stewardship in primary health care influences prescribing by reducing the frequency of prescription [6, 28, 38, 63].

Health system-related factors

In this review, studies reported that organizational-related factors influenced the antibiotic prescribing practice of physicians. The studies conducted by Sharaf, et al. [65], Liu, et al. [67] and Poss-Doering, et al. [66] reported that antibiotic prescribing is affected by the presence of and adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines and protocols for antibiotic use. Quantity and quality of service were also associated with antibiotic prescribing practices and variability of prescribing antibiotics in primary health care physicians [46, 58]. Weak regulation of health systems, the dissemination of medical information, and practice setting characteristics (such as location, level of activities, network participation, and continuing medical education) influenced antibiotic prescribing [30, 32, 33, 47, 58]. Chem, et al. [54] reported that the external pressure of the pharmaceutical industry and over-the-counter antibiotics were factors that influenced the prescribing of antibiotics by physicians. Two other studies reported that biomedical evidence, policy statements and service provision were factors influencing prescribing [44, 63].

Factors for intra- and inter-physician variability in antibiotic prescription

Physicians-related factors

Factors contributing to intra-and inter-physician variability in antibiotic prescriptions are physician’s related factors, such as physicians’ expertise, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, clinical experience, and particular prescription practices. A study conducted in the UK reported that there was large variability in antibiotic prescriptions between and within health care providers for the same condition [25]. Another study also reported that the variation in antibiotic prescriptions in primary health care was due to intra-physician variability (70%), with only 6% due to inter- physician variability [33]. This variation was largely explained by patient characteristics and practice setting characteristics (location, level of activity, continued medical education and network participation) (as shown Table 2). However, a study conducted in Canada reported that the inter-physician variability in prescribing antibiotics could not be explained by patient preference and patient sociodemographic characteristics; rather, it is likely to be related to individual physicians’ prescribing habits [12]. Clinical setting and management were also important factors for inter-prescribing variability in the decision to prescribe antibiotics [12, 32, 34, 42, 52].

Physician affiliations (institutional characteristics) are important factors in understanding the variation in physician antibiotic prescribing practices [58, 71]. Loss of control over prescribing decisions, evidence-based practice, and differences in priorities among different doctors are some of the factors that influence the variability of prescription [27, 29, 49, 50, 55]. More experienced physicians prescribe fewer antibiotics than junior physicians in regular clinical work, particularly during times of uncertainty [8, 37]. Another study conducted in the USA also reported that physicians with higher qualifications (specialties, higher level of expertise) and those with more experience were less likely to prescribe antibiotics [62]. This study also reported that specialized paediatric physicians were more likely to adhere to guidelines for managing the treatment and less likely to prescribe antibiotics without positive tests. The included studies also showed that the majority of practice-level variation in antibiotic prescribing was explained by the variation in physicians’ individual practice patterns, perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge [12, 18, 32, 42, 43] (as shown in Table 2). According to Tang, et al. [59], exposure to different medical cases can have a favourable impact on the variability of antibiotic prescribing patterns of physicians for upper respiratory tract infections. Additionally, interpretations of symptoms, workload, and working at emergency departments lead to variations in prescribing practices [12, 60]. Bharathiraja, et al. [35] explained that factors such as interactions, discussions and exposure to different prescribing behaviours with colleagues and inpatient practice settings influenced antibiotic prescription behaviours.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to provide an overall picture of the current published evidence of factors of antibiotic prescription and variability thereof in primary health care physicians. Various factors could be identified that might influence prescribing practices and contribute to variability in antibiotic prescribing. For a more in-depth understanding, the theses factors are discussed in more detail within the following major themes.

Patient-related factors

In this review, we found that the influence of patients on antibiotic prescription practice emerged as a noteworthy and significant finding. There is evidence that patient attitude, knowledge, or beliefs had an influence on antibiotic prescription in primary healthcare physicians, for example, misconceptions regarding the role of antibiotics regarding the efficacy of antibiotics in treating viral infections and infectious diseases [25, 31, 41, 46, 60, 72]. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Canada that revealed an increase in antibiotic use by patients during the influenza season [73]. Furthermore, this review identified that the perception of what is considered concerning symptoms, the perceived need to consult a physician, and faith in the body's natural healing power, have an impact on antibiotic use [12, 72, 74, 75].

Another piece of evidence we found in this review pertained to the habits and cultural factors of the patients can encourage frequent prescribing and self-medication [63, 64]. This might be the result of cultural norms and traditions may shape individual views on health, favouring for quick relief through antibiotics. These cultural norms and traditions may be influenced by patients’ previous experience with obtaining treatment from other clinicians [36, 56, 76, 77]. Another important point from this review is that the socioeconomic status of patients was all recognized as factors that affect antibiotic prescription [40, 54]. Patients with a high economic status might exert more pressure on physicians to prescribe antibiotics than patients with lower economic status [29, 38, 77, 78].

Physician-related factors

In this review, we found that physicians’ attitudes about antibiotic resistance and prescribing habits influence antibiotic prescribing [30, 46, 74, 79]. A lack of understanding of antibiotic resistance may contribute to the variation in antibiotic prescription. Updating guidelines for physicians on antibiotic prescribing is crucial to emphasize the significance of appropriate antibiotic use in addressing antibiotic resistance issue [45]. Furthermore, clinical experience, such as exposure to infectious disease, influences antibiotic prescription practice [44]. This implies that physicians with more clinical experience and knowledge of Antibiotic stewardship programs tend to prescribe antibiotics less frequently. This is also supported by another study [53], which shows that physicians with high experience in diagnosing and treating various medical conditions exhibited lower prescribing due to their heightened confidence. According to Queder, et al. [18], the physician's attitude toward sustainable use of antibiotics is based on professional experience in prescribing and acquired knowledge about antibiotics. This suggestion is supported by another study [43] junior physicians might be more likely to be guideline oriented than senior physicians.

According to three studies, physicians with high practice volumes are more likely to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately or excessively compared to those with low practice volumes [36, 80, 81]. This indicated that busy physicians’ pressure to treat many patients in a short period of time may make generalized diagnoses, resulting in antibiotic prescribing even when it is not necessary. This aligns with studies indicating physicians prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily to expedite clinic visits and improve patient satisfaction [37, 82, 83]. Physician perception of patients’ expectations of antibiotics are other factors that influence prescribing practice [6, 49]. This finding is also supported by another study conducted in India, where many physicians perceived that patients expect them to prescribe antibiotics after spending money on consultation, which leads to dissatisfaction if antibiotics are not provided. This review notes prescribers are influenced by the desire for positive patient relationships [29, 38, 44, 49, 53]. This indicates that physicians may assume that patients want antibiotics to boost satisfaction [84,85,86]. According to Schwartz, et al. [12], family physicians show significant variability in antibiotic prescribing not entirely explained by patients’ characteristics. This might be due to the financial incentive for prescribers, and lack of continuous medical education.

In this review, we found that antibiotic prescription practices are highly influenced by medical colleagues’ prescribing behaviour and conduct [6, 37]. A previous systematic review noted that physicians often share insights, and seek advice from their colleagues, which may shape their approach to antibiotic prescription [87]. Studies from Ireland and the UK reported that a hierarchical system, particularly senior colleagues, influenced physicians’ antibiotic prescribing practices [88, 89]. These hieratical influence can significantly shape physician prescribing decisions but misunderstandings of the responsibilities and roles pose obstacles to antibiotic prescription.

Health system-related factors

Another factor found in this review shows that antibiotic prescribing can vary significantly based on the resources available, financial capacity, and regulation of the healthcare setting. In a setting where formal guidelines are lacking regarding antibiotic prescriptions, physicians often rely on their individual knowledge and previous experience, which may result in over prescription or inadequate use of antibiotics [47, 64, 90]. According to Harbarth and Samore [91], clinical guidelines that specifically tailored to the situation, governing over-the-counter prescription of antibiotics, resulted in reduced antibiotic use. In this review, we found that healthcare system norms and culture significant influence antibiotics prescribing [62, 64]. The setting that prioritizes communication and encourages discussion can lead to more precise and targeted antibiotic prescription practices. Ness, et al. [92] and Skodvin, et al. [37] noted that financial incentives and healthcare regulations influence antibiotic prescription. A study conducted in Japan reported that financial incentives to medical facilities for not prescribing antibiotics resulted in reduced antibiotic prescribing [93].

Interventions to address major factors influencing variation of antibiotic prescription

This review found that the variation in antibiotic prescribing practice was due to intra- and inter-physician variability in response to factors related to patients, physicians and health system. This review presents major factors that could be targeted for developing interventions (Table 3).

As a result, the research that clarifies and subsequently demonstrates which factors have a significant effect on the variability of antibiotic prescription makes a significant contribution to developing interventions that are efficient and successful.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review is that we included all study designs to summarize the available evidence. This review solely focused on physicians, and we did not include nurses, pharmacists, caregivers and other healthcare professionals, who may have a role and/or influence in the prescription of antibiotics. These actors often interact closely with patients and have their knowledge, preference and responsibilities regarding antibiotic prescription. Another limitation of this study was that most of the studies were conducted in developed countries, which limits understanding of developing countries where care settings and sociocultural factors may vary. Only studies published in English were reviewed. The included studies used different methodologies leading to methodological heterogeneity, this make it challenging to synthesize findings and draw meaningful comparison.

The implication of the results for practice, policy and future research

In this review, we observed that patient-and physicians-related factors contribute significantly to the variation in antibiotic prescription. Implementing patient-centred intervention such as shared decision-making could be effective strategy to reduce this variation [38, 53]. However, this review highlights that there is a need to understand the variability of antibiotic prescriptions between and within physicians. Variation in antibiotic prescribing practices is poorly explained in the included studies, despite justifiable differences in prescription volume. Therefore, confirming the precise reason for the encounter helps reduce the variability of antibiotic prescription in primary health care. Antibiotic prescriptions by allied healthcare professionals, including clinical pharmacists, physician assistants, have increased in primary healthcare settings in recent years [94, 95]. However, their roles were not evaluated in this study, so this needs further investigation.

Furthermore, physicians may prescribe less if management encourages intra-professional discussion within the practice, internalized guidelines, and management of patient expectations across the practice. Moreover, the majority of the studies in this review were carried out in developed nations, indicating the importance of conducting research in a diversity of healthcare settings to understand the contextual factors that affect prescribing and tailoring interventions accordingly.

Conclusion

In general, variation in antibiotic prescribing among primary health care physicians is explained by several different factors. The major factors that contribute to this variation include physician experience and individual practice patterns, time constraints, physician perceptions and attitudes, colleagues' influence, and patient-related factors (perception and attitudes toward antibiotics). Our review indicates that the level of clinical experience and the use of guidelines counteract the effect of patient expectations on prescribing practices. Variations in antibiotic prescriptions among healthcare professionals in the primary healthcare setting could contribute to increased antibiotic resistance. Thus, studies on the drivers of prescribing habits can guide antibiotic stewardship program efforts. Finally, we suggest that to address factors that influence the variability of antibiotic prescription, interventions should aim to provide continued medical education and training and promote patient-centred care.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript. For any further data, it can be accessible from corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO: Global online consultation: a people-centred framework for addressing antimicrobial resistance in the human health sector 2023 [https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/global-online-consultation-people-centred-framework-for-addressing-antimicrobial-resistance-in-the-human-health-sector]. Accessed at 13 Jul, 2023.

WHO: WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016–2018 early implementation. 2019 [https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-report-on-surveillance-of-antibiotic-consumption]. Accessed 20 Jun 2023.

Jones BE, Sauer B, Jones MM, Campo J, Damal K, He T, Ying J, Greene T, Goetz MB, Neuhauser MM. Variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in the veteran population: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):73–80.

Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, Friedberg MW, Persell SD, Goldstein NJ, Knight TK, Hay JW, Doctor JN. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562–70.

van Esch TEM, Brabers AEM, Hek K, van Dijk L, Verheij RA, de Jong JD. Does shared decision-making reduce antibiotic prescribing in primary care? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3199–205.

Lum EP, Page K, Whitty JA, Doust J, Graves N. Antibiotic prescribing in primary healthcare: dominant factors and trade-offs in decision-making. Infect Dis Health. 2018;23(2):74–86.

Andersson DI, Balaban NQ, Baquero F, Courvalin P, Glaser P, Gophna U, Kishony R, Molin S, Tønjum T. Antibiotic resistance: turning evolutionary principles into clinical reality. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;44(2):171–88.

Aabenhus R, Siersma V, Sandholdt H, Køster-Rasmussen R, Hansen MP, Bjerrum L. Identifying practice-related factors for high-volume prescribers of antibiotics in Danish general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(8):2385–91.

Collignon P, Beggs JJ, Walsh TR, Gandra S, Laxminarayan R. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(9):e398–405.

Cangini A, Fortinguerra F, Di Filippo A, Pierantozzi A, Da Cas R, Villa F, Trotta F, Moro ML, Gagliotti C. Monitoring the community use of antibiotics in Italy within the National Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(3):1033–42.

Ahmed RR, Streimikiene D, Abrhám J, Streimikis J, Vveinhardt J. Social and behavioral theories and physician’s prescription behavior. Sustainability. 2020;12(8):3379.

Schwartz KL, Brown KA, Etches J, Langford BJ, Daneman N, Tu K, Johnstone J, Achonu C, Garber G. Predictors and variability of antibiotic prescribing amongst family physicians. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(7):2098–105.

Cantarero-Arevalo L, Nørgaard LS, Sporrong SK, Jacobsen R, Almarsdóttir AB, Hansen JM, Titkov D, Rachina S, Panfilova E, Merkulova V. A qualitative analysis of the culture of antibiotic use for upper respiratory tract infections among patients in Northwest Russia. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:800695.

Manne M, Deshpande A, Hu B, Patel A, Taksler GB, Misra-Hebert AD, Jolly SE, Brateanu A, Bales RW, Rothberg MB. Provider Variation in Antibiotic Prescribing and Outcomes of Respiratory Tract Infections. South Med J. 2018;111(4):235–42.

Dolk FCK, Pouwels KB, Smith DR, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Antibiotics in primary care in England: which antibiotics are prescribed and for which conditions? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(suppl_2):ii2–10.

Howarth T, Brunette R, Davies T, Andrews RM, Patel BK, Tong S, Barzi F, Kearns TM. Antibiotic use for Australian Aboriginal children in three remote Northern Territory communities. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231798.

Durand C, Alfandari S, Béraud G, Tsopra R, Lescure F-X, Peiffer-Smadja N. Clinical Decision Support Systems for Antibiotic Prescribing: An Inventory of Current French Language Tools. Antibiotics. 2022;11(3):384.

Queder A, Arnold C, Wensing M, Poß-Doering R. Contextual factors influencing physicians’ perception of antibiotic prescribing in primary care in Germany—a prospective observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–11.

Warreman E, Lambregts M, Wouters R, Visser L, Staats H, Van Dijk E, De Boer M. Determinants of in-hospital antibiotic prescription behaviour: a systematic review and formation of a comprehensive framework. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(5):538–45.

van der Velden AW, van de Pol AC, Bongard E, Cianci D, Aabenhus R, Balan A, Böhmer F, Lang VB, Bruno P, Chlabicz S. Point-of-care testing, antibiotic prescribing, and prescribing confidence for respiratory tract infections in primary care: a prospective audit in 18 European countries. BJGP open. 2022;6(2):BJGPO.2021.0212.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Rodrigues AT, Roque F, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41(3):203–12.

Frantzen KK, Fetters MD. Meta-integration for synthesizing data in a systematic mixed studies review: insights from research on autism spectrum disorder. Qual Quant. 2016;50:2251–77.

Palin V, Mölter A, Belmonte M, Ashcroft DM, White A, Welfare W, van Staa T. Antibiotic prescribing for common infections in UK general practice: variability and drivers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(8):2440–50.

Theodorou M, Tsiantou V, Pavlakis A, Maniadakis N, Fragoulakis V, Pavi E, Kyriopoulos J. Factors influencing prescribing behaviour of physicians in Greece and Cyprus: results from a questionnaire based survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:1–9.

Chan Y, Ibrahim MB, Wong C, Ooi C, Chow A. Determinants of antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in an emergency department with good primary care access: a qualitative analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e111.

Ahmadi F, Zarei E. Prescribing patterns of rural family physicians: a study in Kermanshah Province Iran. Bmc Public Health. 2017;17(1):908.

Kotwani A, Wattal C, Katewa S, Joshi P, Holloway K. Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):684–90.

Fletcher-Lartey S, Yee M, Gaarslev C, Khan R. Why do general practitioners prescribe antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections to meet patient expectations: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e012244.

Laka M, Milazzo A, Merlin T. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing: understanding clinicians’ perceptions to enable changes in prescribing practices. Aust Health Rev. 2021;46(1):21–7.

Swe MMM, Ashley EA, Althaus T, Lubell Y, Smithuis F, Mclean AR. Inter-prescriber variability in the decision to prescribe antibiotics to febrile patients attending primary care in Myanmar. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(1):dlaa118.

Mousquès J, Renaud T, Scemama O. Is the “practice style” hypothesis relevant for general practitioners? An analysis of antibiotics prescription for acute rhinopharyngitis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(8):1176–84.

Björnsdóttir I, Kristinsson KG, Hansen EH. Diagnosing infections: a qualitative view on prescription decisions in general practice over time. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(6):805–14.

Bharathiraja R, Sridharan S, Chelliah LR, Suresh S, Senguttuvan M. Factors affecting antibiotic prescribing pattern in pediatric practice. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72(10):877–9.

Cadieux G, Tamblyn R, Dauphinee D, Libman M. Predictors of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care physicians. CMAJ. 2007;177(8):877–83.

Skodvin B, Aase K, Charani E, Holmes A, Smith I. An antimicrobial stewardship program initiative: a qualitative study on prescribing practices among hospital doctors. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4(1):1–8.

Guo H, Hildon ZJ-L, Loh VWK, Sundram M, Ibrahim MAB, Tang WE, Chow A. Exploring antibiotic prescribing in public and private primary care settings in Singapore: a qualitative analysis informing theory and evidence-based planning for value-driven intervention design. BMC Family Practice. 2021;22:1–14.

Borek A, Anthierens S, Allison R, Mcnulty C, Anyanwu P, Costelloe C, Walker A, Butler C, Tonkin-Crine S. Social and Contextual Influences on Antibiotic Prescribing and Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Qualitative Study with Clinical Commissioning Group and General Practice Professionals. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(12):859 (In.; 2020).

Béjean S, Peyron C, Urbinelli R. Variations in activity and practice patterns: a French study for GPs. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8:225–36.

Sydenham RV, Jarbøl DE, Hansen MP, Justesen US, Watson V, Pedersen LB. Prescribing antibiotics: Factors driving decision-making in general practice. A discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2022;305:115033.

Pouwels KB, Dolk FCK, Smith DR, Smieszek T, Robotham JV. Explaining variation in antibiotic prescribing between general practices in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(suppl_2):ii27–35.

Paluck E, Katzenstein D, Frankish CJ, Herbert CP, Milner R, Speert D, Chambers K. Prescribing practices and attitudes toward giving children antibiotics. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47(3):521–7.

Kumar S, Little P, Britten N. Why do general practitioners prescribe antibiotics for sore throat? Grounded theory interview study. BMJ. 2003;326(7381):138.

Simpson SA, Wood F, Butler CC. General practitioners’ perceptions of antimicrobial resistance: a qualitative study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(2):292–6.

Wood F, Simpson S, Butler CC. Socially responsible antibiotic choices in primary care: a qualitative study of GPs’ decisions to prescribe broad-spectrum and fluroquinolone antibiotics. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):427–34.

Reynolds L, McKee M. Factors influencing antibiotic prescribing in China: an exploratory analysis. Health Policy. 2009;90(1):32–6.

Bjorkman I, Berg J, Roing M, Erntell M, Lundborg CS. Perceptions among Swedish hospital physicians on prescribing of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e8.

Björkman I, Erntell M, Röing M, Lundborg CS. Infectious disease management in primary care: perceptions of GPs. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):1–8.

Vazquez-Lago JM, Lopez-Vazquez P, Lopez-Duran A, Taracido-Trunk M, Figueiras A. Attitudes of primary care physicians to the prescribing of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance: a qualitative study from Spain. Fam Pract. 2012;29(3):352–60.

Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheij TJ. Determinants of antibiotic overprescribing in respiratory tract infections in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(5):930–6.

Wester CW, Durairaj L, Evans AT, Schwartz DN, Husain S, Martinez E. Antibiotic resistance: a survey of physician perceptions. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2210–6.

van der Zande MM, Dembinsky M, Aresi G, van Staa TP. General practitioners’ accounts of negotiating antibiotic prescribing decisions with patients: a qualitative study on what influences antibiotic prescribing in low, medium and high prescribing practices. Bmc Family Practice. 2019;20(1):172.

Chem ED, Anong DN, Akoachere JKT. Prescribing patterns and associated factors of antibiotic prescription in primary health care facilities of Kumbo East and Kumbo West Health Districts, North West Cameroon. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193353.

Beilfuss S, Linde S, Norton B. Accountable care organizations and physician antibiotic prescribing behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114707.

Zetts RM, Stoesz A, Garcia AM, Doctor JN, Gerber JS, Linder JA, Hyun DY. Primary care physicians’ attitudes and perceptions towards antibiotic resistance and outpatient antibiotic stewardship in the USA: a qualitative study. Bmj Open. 2020;10(7):e034983.

Rodrigues AT, Nunes JCF, Estrela M, Figueiras A, Roque F, Herdeiro MT. Comparing Hospital and Primary Care Physicians’ Attitudes and Knowledge Regarding Antibiotic Prescribing: A Survey within the Centre Region of Portugal. Antibiotics-Basel. 2021;10(6):629.

Alradini F, Bepari A, AlNasser BH, AlGheshem EF, AlGhamdi WK. Perceptions of primary health care physicians about the prescription of antibiotics in Saudi Arabia: Based on the model of Theory of planned behaviour. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(12):1416–25.

Tang YQ, Liu CX, Zhang XP. Performance associated effect variations of public reporting in promoting antibiotic prescribing practice: a cluster randomized-controlled trial in primary healthcare settings. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18(5):482–91.

Rodrigues AT, Ferreira M, Pineiro-Lamas M, Falcao A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Determinants of physician antibiotic prescribing behavior: a 3 year cohort study in Portugal. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(5):949–57.

Al-Homaidan HT, Barrimah IE. Physicians’ knowledge, expectations, and practice regarding antibiotic use in primary health care. Int J Health Sci Ijhs. 2018;12(3):18–24.

Frost HM, McLean HQ, Chow BD. Variability in antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory illnesses by provider specialty. J Pediatr. 2018;203(76–85):e78.

Karimi G, Kabir K, Farrokhi B, Abbaszadeh E, Esmaeili ED, Khodamoradi F, Sarbazi E, Azizi H. Prescribing pattern of antibiotics by family physicians in primary health care. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2023;16(1):11.

Huang Z, Weng Y, Ang H, Chow A. Determinants of antibiotic over-prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in an emergency department with good primary care access: a quantitative analysis. J Hosp Infect. 2021;113:71–6.

Sharaf N, Al-Jayyousi GF, Radwan E, Shams Eldin SME, Hamdani D, Al-Katheeri H, Elawad K, Habib SA. Barriers of appropriate antibiotic prescription at PHCC in Qatar: perspective of physicians and pharmacists. Antibiotics. 2021;10(3):317.

Poss-Doering R, Kuhn L, Kamradt M, Sturmlinger A, Glassen K, Andres E, Kaufmann-Kolle P, Wambach V, Bader L, Szecsenyi J, et al. Fostering Appropriate Antibiotic Use in a Complex Intervention: Mixed-Methods Process Evaluation Alongside the Cluster-Randomized Trial ARena. Antibiotics-Basel. 2020;9(12):878.

Liu CX, Liu CJ, Wang D, Zhang XP. Intrinsic and external determinants of antibiotic prescribing: a multi-level path analysis of primary care prescriptions in Hubei, China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):132.

Cordoba G, Caballero L, Sandholdt H, Arteaga F, Olinisky M, Ruschel LF, Makela M, Bjerrum L. Antibiotic prescriptions for suspected respiratory tract infection in primary care in South America. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(1):305–10.

Liu CX, Zhang XP, Wang X, Zhang XP, Wan J, Zhong FY. Does public reporting influence antibiotic and injection prescribing to all patients? A cluster-randomized matched-pair trial in china. Medicine. 2016;95(26):e3965.

Zhang ZX, Zhan XX, Zhou HJ, Sun F, Zhang H, Zwarenstein M, Liu Q, Li YX, Yan WR. Antibiotic prescribing of village doctors for children under 15 years with upper respiratory tract infections in rural China A qualitative study. Medicine. 2016;95(23):e3803.

Brookes-Howell L, Elwyn G, Hood K, Wood F, Cooper L, Goossens H, Ieven M, Butler CC. “The Body Gets Used to Them”: Patients’ Interpretations of Antibiotic Resistance and the Implications for Containment Strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(7):766–72.

van Duijn HJ, Kuyvenhoven MM, Tiebosch HM, Schellevis FG, Verheij TJ. Diagnostic labelling as determinant of antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract episodes in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:55.

McKay R, Mah A, Law MR, McGrail K, Patrick DM. Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4106–18.

Rosman S, Le Vaillant M, Schellevis F, Clerc P, Verheij R, Pelletier-Fleury N. Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections in general practice in France and in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(3):312–6.

Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2010;340:c2096.

Avorn J, Solomon DH. Cultural and economic factors that (mis)shape antibiotic use: the nonpharmacologic basis of therapeutics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(2):128–35.

Tähtinen PA, Boonacker CW, Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Huovinen P, Liuksila PR, Ruuskanen O, Ruohola A. Parental experiences and attitudes regarding the management of acute otitis media–a comparative questionnaire between Finland and The Netherlands. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):488–92.

Barbieri JS, Fix WC, Miller CJ, Sobanko JF, Shin TM, Howe N, Margolis DJ, Etzkorn JR. Variation in Prescribing and Factors Associated With the Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics for Mohs Surgery: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(7):868–75.

Cole A. GPs feel pressurised to prescribe unnecessary antibiotics, survey finds. BMJ. 2014;349:g5238.

Daneman N, Campitelli MA, Giannakeas V, Morris AM, Bell CM, Maxwell CJ, Jeffs L, Austin PC, Bronskill SE. Influences on the start, selection and duration of treatment with antibiotics in long-term care facilities. CMAJ. 2017;189(25):E851-e860.

Agiro A, Gautam S, Wall E, Hackell J, Helm M, Barron J, Zaoutis T, Fleming-Dutra KE, Hicks LA, Rosenberg A. Variation in Outpatient Antibiotic Dispensing for Respiratory Infections in Children by Clinician Specialty and Treatment Setting. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(12):1248–54.

Ong S, Nakase J, Moran GJ, Karras DJ, Kuehnert MJ, Talan DA. Antibiotic use for emergency department patients with upper respiratory infections: prescribing practices, patient expectations, and patient satisfaction. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(3):213–20.

Hart AM, Pepper GA, Gonzales R. Balancing acts: Deciding for or against antibiotics in acute respiratory infections. J Fam Pract. 2006;55(4):320–5.

Teixeira Rodrigues A, Ferreira M, Pineiro-Lamas M, Falcao A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Determinants of physician antibiotic prescribing behavior: a 3 year cohort study in Portugal. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(5):949–57.

Coenen S, Gielen B, Blommaert A, Beutels P, Hens N, Goossens H. Appropriate international measures for outpatient antibiotic prescribing and consumption: recommendations from a national data comparison of different measures. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(2):529–34.

Ternhag A, Grünewald M, Nauclér P, Wisell KT. Antibiotic consumption in relation to socio-demographic factors, co-morbidity, and accessibility of primary health care. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(12):888–96.

Wojcik G, Ring N, McCulloch C, Willis DS, Williams B, Kydonaki K. Understanding the complexities of antibiotic prescribing behaviour in acute hospitals: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):134.

De Souza V, MacFarlane A, Murphy AW, Hanahoe B, Barber A, Cormican M. A qualitative study of factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing by non-consultant hospital doctors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(4):840–3.

Mattick K, Kelly N, Rees C. A window into the lives of junior doctors: narrative interviews exploring antimicrobial prescribing experiences. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(8):2274–83.

Grossman Z, del Torso S, Hadjipanayis A, van Esso D, Drabik A, Sharland M. Antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory infections: European primary paediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and practice. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(9):935–40.

Harbarth S, Samore MH. Antimicrobial resistance determinants and future control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(6):794–801.

Ness V, Price L, Currie K, Reilly J. Influences on independent nurse prescribers’ antimicrobial prescribing behaviour: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(9–10):1206–17.

Okubo Y, Nishi A, Michels KB, Nariai H, Kim-Farley RJ, Arah OA, Uda K, Kinoshita N, Miyairi I. The consequence of financial incentives for not prescribing antibiotics: a Japan’s nationwide quasi-experiment. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51(5):1645–55.

Koller D, Hoffmann F, Maier W, Tholen K, Windt R, Glaeske G. Variation in antibiotic prescriptions: is area deprivation an explanation? Analysis of 1.2 million children in Germany Analysis million children in Germany. Infection. 2013;41(1):121–7.

Weiss MC. The rise of non-medical prescribing and medical dominance. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(3):632–7.

Li Y, Mölter A, Palin V, Belmonte M, Sperrin M, Ashcroft DM, White A, Welfare W, Van Staa T. Relationship between prescribing of antibiotics and other medicines in primary care: A cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):E42–51.

Pouwels KB, Hopkins S, Llewelyn MJ, Walker AS, McNulty CA, Robotham JV. Duration of antibiotic treatment for common infections in English primary care: Cross sectional analysis and comparison with guidelines. BMJ (Online). 2019;364:l440.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank you librarian Jane Lally at the University of New England for her consultation on the search strategy.

Funding

This review did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GEK drafted and edited the review. MSI, JH and SC critically revised and edited the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Appraisal of the methodological quality.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kasse, G.E., Humphries, J., Cosh, S.M. et al. Factors contributing to the variation in antibiotic prescribing among primary health care physicians: a systematic review. BMC Prim. Care 25, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02223-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02223-1