Abstract

Background

Prompt, effective CPR greatly increases the chances of survival in out-of-hospital c ardiac arrest. However, it is often not provided, even by people who have previously undertaken training. Psychological and behavioural factors are likely to be important in relation to CPR initiation by lay-people but have not yet been systematically identified.

Methods

Aim: to identify the psychological and behavioural factors associated with CPR initiation amongst lay-people.

Design: Systematic review

Data sources: Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Google Scholar.

Study eligibility criteria: Primary studies reporting psychological or behavioural factors and data on CPR initiation involving lay-people published (inception to 31 Dec 2021).

Study appraisal and synthesis methods: Potential studies were screened independently by two reviewers. Study characteristics, psychological and behavioural factors associated with CPR initiation were extracted from included studies, categorised by study type and synthesised narratively.

Results

One hundred and five studies (150,820 participants) comprising various designs, populations and of mostly weak quality were identified. The strongest and most ecologically valid studies identified factors associated with CPR initiation: the overwhelming emotion of the situation, perceptions of capability, uncertainty about when CPR is appropriate, feeling unprepared and fear of doing harm. Current evidence comprises mainly atheoretical cross-sectional surveys using unvalidated measures with relatively little formal testing of relationships between proposed variables and CPR initiation.

Conclusions

Preparing people to manage strong emotions and increasing their perceptions of capability are likely important foci for interventions aiming to increase CPR initiation. The literature in this area would benefit from more robust study designs.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO: CRD42018117438.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) has a devastatingly high mortality rate [1]. Survival to hospital discharge ranges between countries from < 1% [2] to 25% in the best European centres [3], reflecting differences in case identification, demography, geography and emergency service provision [4]. Reducing the mortality associated with OHCA is a strategic priority of many countries [5,6,7,8,9,10].

Prompt, effective bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the most important factor determining survival from OHCA, increasing survival almost 4-fold [11, 12]. Registry data show most OHCA occur at home [2, 13, 14]. Even the most prompt emergency medical response will take at least a few minutes (median 6 mins.) [15], and so the response of others in the home is critical.

Governments and charities invest significantly in training lay-people in CPR [16,17,18]. Despite this, those in OHCA often do not receive CPR prior to the arrival of emergency services [19]. Even amongst those who are trained, less than half attempt CPR when required [20]. Increasing the proportion of lay-people trained in CPR who actually apply their skills in a real emergency situation is essential [21] as otherwise much of the effort expended in training lay-people will not improve outcomes for patients.

Research relating to CPR training of lay-people has largely been concerned with increasing knowledge and achieving competence in the skill of CPR. Questions of how best to teach CPR tend to be answered by studies using skills performance (e.g. compression depth) and assessment of knowledge as outcome measures [22, 23]. However the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation [24] and behavioural science [25] would suggest that psychological factors (e.g. people’s attitudes about CPR) are likely to be critical in explaining whether or not people initiate CPR. To date there has not been a systematic synthesis of this literature.

The aim of this review was to synthesise evidence relating to lay-people initiating CPR and to identify the psychological and behavioural factors that facilitate or inhibit people’s willingness to perform CPR.

Method

Protocol and registration

In line with best practice, a review protocol was published (2018) and registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of systematic reviews (protocol number 117438): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=117438.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

Types of study

All primary study designs.

Types of participants

Lay members of the public (i.e. not healthcare professionals or others who receive CPR training as a part of their job, e.g. lifeguards) of any age.

Types of outcome measure

Studies which contained psychological/behavioural data (not CPR knowledge or training status) related to 1) why the participants did or did not perform CPR in real emergencies or 2) would or would not perform CPR in a hypothetical or simulated situation. CPR was defined as performing chest compressions (CC), mouth-to-mouth ventilations, applying an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) or any combination of these.

Exclusion

Papers which did not report a primary empirical study (e.g. reviews, editorials, opinion pieces) were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

Six electronic databases - Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Google Scholar- were searched for publications from inception of each database to 13th December 2019 (search strategy is supplied in supplementary materials Additional file 1). Supplementary searches included: a) reference lists of included studies, b) citations of included studies (Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), c) hand-searches of titles (Jan 2005 – Jan 2020) of Resuscitation and a further update database search performed 01/06/21.

Study selection

Screening of titles was undertaken independently by two reviewers (BF and DD) to exclude titles that were obviously irrelevant. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to abstracts of studies and irrelevant abstracts were excluded. Inter-rater agreement kappa was 0.85, pabak kappa = 0.85. Full texts considered potentially relevant by either reviewer were screened independently (BF and DD). At full-text stage, any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies [26] and the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Quality Assessment and Review Instrument (QARI) for qualitative studies [27]. Included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (BF and CT) for methodological quality, with discrepancies being resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Guided by the CONSORT guidelines [28] and the published protocol, the following data were extracted for each study: study details (author & date, location, study duration, objectives), study methods (design, setting, target population, sample size estimation, actual sample size, sampling and recruitment method, behavioural and psychological data, analysis, dates of recruitment) and study results.

BF and SM independently performed data extraction on 20% of the included studies (n = 20) to assess reliability. No discrepancies in independently extracted data were found and the remainder were extracted by a single researcher (BF or SM).

Synthesis and analysis

Behavioural and psychological factors identified during extraction were grouped into conceptually similar ‘factors’ by BF: 51 individual factors were identified. To facilitate interpretation, this large number of factors were grouped using categorisations or domains from the Theoretical Domains Framework Version 2 [29] (a validated, comprehensive, theory-informed approach to identifying determinants of behaviour). Definition of domains referred to in this paper are provided in Box 1. Domain categorisations were confirmed by a second reviewer (DD).

Included studies were differentiated according to the study population, study design and whether factors were identified by participants in response to an open question or endorsed from a list of factors presented by researchers. In order to facilitate comparisons studies were grouped according to the summary statistics used and p-values and Odds Ratios compared where possible. We prioritised 1) the most ecologically valid data [30, 31] (i.e. real-life OHCA calls and accounts of people who had actually witnessed OHCA), 2) studies which formally assessed posited relationships and 3) methodologically strong studies (i.e. assessed as low risk of bias) in the findings section.

Results

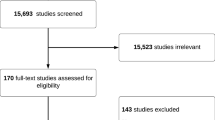

Original database searches conducted on 13th Dec 2018 (see PRISMA diagram, Fig. 1) identified 17,309 citations with 87 studies included after screening for eligibility. An update search conducted 01/06/21 identified 1119 additional titles, 15 of which were assessed as eligible. Hand-searching of Resuscitation (Jan 2005-Dec 2021) identified 96 potentially relevant titles, seven of which had not already been identified by database screening, none met the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of included studies identified an additional 136 papers, 26 of which had not been previously identified, two studies were eligible and included. Finally, citation tracking identified 35 potentially relevant titles, seven not previously screened and one study included. Therefore, a total of 105 studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

Description of included studies

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the 105 included studies comprising a total of 150,820 participants. The studies were published between 1989 and 2021 and conducted across 30 countries. The studies were heterogenous in design and included: randomised controlled trials (n = 6); non-randomised trials (n = 1); a quasi-experimental deign (n = 1), prospective cohort study (n = 1); before and after studies (n = 15); cross sectional studies (n = 67), qualitative studies (n = 9) and studies examining actual OHCA calls to Emergency Medical Services (n = 5).

Methodological quality

Of the quantitative studies, four [58, 69, 103, 110] were identified as strong, six as moderate [83, 90, 102, 117, 125, 131] with the remaining 87 quantitative studies rated ‘weak’ (see Table 2). There was a predominance of non-randomised designs, uncontrolled confounders, and use of unvalidated data collection methods. All qualitative studies were assessed as of sufficient quality for inclusion but also varied in quality (n = 8).

The psychological and behavioural factors identified from the included studies are reported below and summarised in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 below. Studies were divided into subgroups according to the study population (i.e. results from those with direct experience versus general samples responding to a ‘hypothetical’ OHCA); study design and statistics used. Data were further categorised depending on whether the ‘predictor’ was identified by participants in response to an open question or whether it was presented as a possible factor and subsequently endorsed. Factors are presented in relation to the domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework so that theoretically similar factors are grouped together and can be compared across study designs (Fig. 2).

Theoretical Domains Framework definitions [29]

Studies involving those with direct experience of OHCA

Sixteen studies involving people with direct experience of OHCA were identified. These included five studies which analysed recorded calls involving OHCA [47, 58, 67, 83, 110], four qualitative studies exploring the experiences of people who had witnessed an OHCA [93, 94, 98, 130] and seven cross-sectional surveys which asked open questions about people’s experiences of facilitators and barriers to them having performed CPR [20, 36, 46, 95, 122, 126, 136].

Real-life calls

TDF domain 4: beliefs about capabilities

Limitations in the physical capacity of the caller was also identified in all five studies. Physical capability was a barrier to CPR in 15% [47], 51% [58], 11% [67], 35% [110] and 8% [83] of calls. Difficulties moving the person who had collapsed to a flat position in order to perform CPR and the rescuer being frail or with a condition making CPR difficult were described. Uncertainty about whether cardiac arrest was happening (e.g. person still making some respiratory sounds) was reported in 28% of calls by Case (2018) [47] and in 6% by Hauff (2003) [67].

Case (2018) [47] reported that “many callers” reported a lack of confidence.

TDF domain 6: beliefs about consequences

Concerns that CPR was futile (e.g. that the person was already dead/beyond help) were reported in 50% of calls analysed by Riou et al. (2020) [110], in 28% of calls analysed by Case (2018) [47] and in 23% by Hauff (2003) [67]. Concern about infection (4%) [58], fear of doing harm (3%) and fear of legal consequences (1%) [83] were reported in a small minority of calls.

TDF domain 11: environmental context

Disagreeable characteristics associated with the victim was identified as a factor in 3% [83] and 2% [67] of calls.

TDF domain 13: emotion

All five studies of real-life calls analysed calls where the layperson hesitated or refused to provide CPR identified the strong emotion of the situation as a factor that prevented initiation of CPR. Elements of emotional distress, such as panic, upset and stress were identified in 20% [47], 42% [58], 11% [67] and 14% [83] of calls where callers expressed reluctance. ‘Being shaken’ and ‘fear’ were described in 2 example quotations by Riou et al. (2020) [110].

Qualitative studies of people who have witnessed OHCA

Four qualitative accounts of people’s experiences of encountering OHCA and CPR were identified [93, 94, 98, 130] comprising interviews with a total of 107 participants (aged 24 [93] to 87 [130]).

TDF domain 2: skills

Feeling unprepared as to what to expect in a cardiac arrest was a theme identified by Mausz (2018) [94] and Moller (2014) [98], in particular that reality was very different from training with a manikin [98].

TDF domain 3: social/professional role and identity

A sense of community or social responsibility were described as encouraging performance of CPR, some stating it was expected of any responsible citizen [93].

TDF domain 4: beliefs about capabilities

Problems identifying whether cardiac arrest had actually occurred (and thus whether CPR was indicated) were identified [93, 94].

TDF domain 6: beliefs about consequences

Fear of doing the patient harm was identified as a cause for hesitation [130]. Recognising the extreme seriousness of the situation led people to erroneously assume that the person was already dead and that CPR would be futile [130]. However, anticipating feeling guilty if they didn’t perform CPR and the person died as a result was a motivation for participants [93].

Concerns about personal safety [93] and liability in the context of a workplace [94] were also expressed.

TDF domain 11: emotion

Participants also described experiencing panic and extreme emotions which inhibited their ability to perform CPR actions [94, 130].

Cross-sectional surveys

Eight cross sectional surveys included analyses of barriers and facilitators of CPR identified by participants who had direct experience of OHCA [20, 46, 93, 95, 100, 122, 126, 136]. Issues identified were very similar to those already described above in the qualitative studies:

Studies of participants where direct experience of CPR was not required

Studies examining the relationship between psychological/behavioural variables and willingness/confidence/intention to perform CPR

Thirteen studies formally explored the relationship between behavioural and psychological predictor variables and willingness to initiate CPR (see Table 5).

TDF domain 1: knowledge

Knowing the importance of CPR (OR 1.9) was positively and significantly related to willingness to perform CPR [80].

TDF domain 2: skills

Having previous experience of CPR or OHCA was the strongest predictor of anticipated willingness to perform CPR [80, 113, 116]. Odds ratios across four studies ranged from 1.5 [68] to 4.8 [113].

TDF domain 4: beliefs about capabilities

Those with good self-rated health status (AOR, 1.26) were more likely to report that they could provide bystander CPR than those reporting poor health [111] and feeling confident (OR 1.9) [119] was positively and significantly related to willingness to perform CPR [97]. Perceiving a lack of expertise was negatively related to willingness (OR 0.6) [119]. Nolan et al. (1999) [101] also showed that confidence differed significantly between those willing and unwilling to initiate CPR. Those unwilling to act also perceived a greater number of psychosocial barriers than those willing (p ≤ .05).

Vaillancourt (2013) [131] and Magid (2019) [92] explored the ability of constructs from the Theory of Planned Behaviour, to predict intention to perform CPR in the event of a cardiac arrest. Attitudes (e.g. I could save someone’s life with CPR) were with the strongest predictor of respondents’ intentions to perform CPR (OR 1.63) identified by Vaillancourt (2013) and also found to be significant in predicting intention to perform CPR. Similarly, both Vaillancourt (2013) and Magid (2019) found higher control beliefs (I feel confident in my abilities to perform CPR) to be significantly related to increased intentions to perform CPR on a cardiac arrest victim (OR 1.16) [131].

Domain 12: social influences

Normative beliefs (derived from the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)) (e.g. My friends and family expect me to do CPR) were found to be modestly but significantly related to people’s intentions to perform CPR on a cardiac arrest victim (OR: 1.07) [131]. Magid (2019) [92] also found subjective norms predictive of intention to perform CPR.

TDF domain 13: emotion

Nolan et al. (1990) [101] showed that confidence differed significantly between those willing and unwilling to initiate CPR. Those unwilling to act anticipated a higher number of negative emotions (afraid, sad, angry, anxious, confused) if they were to perform CPR compared to those who were willing to act (p ≤ .02).

Studies which have compared responses to scenarios -varying psychological/behavioural factors

Sixty-two studies explored a variety of other factors related to willingness to perform CPR (see Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). Respondents were more willing to perform CPR on their family and friends compared to strangers and in situations that did not involve disagreeable characteristics (TDF Domain 11: Environmental context and resources).

Respondents were more willing to perform compression-only CPR compared to mouth-to-mouth CPR and in situations where there was a perceived risk of transmissible infection willingness to perform CPR was reduced, e.g. after a SARS outbreak (TDF Domain 6: Beliefs about consequences).

Studies of people’s anticipated barriers and facilitators to CPR

Qualitative studies

Four studies provided qualitative accounts of people’s perceptions of CPR [61, 114, 115, 135]. Many of the barriers anticipated by participants in these studies were similar to those identified by people with direct experience of OHCA, as reported above. Additionally, issues around a general fear of ‘getting involved’ with possible consequences in relation to immigration status/law enforcement [115] were identified (TDF Domain 6: Beliefs about Consequences).

Cross-sectional data

Twelve studies [32, 39, 51, 60, 71, 73,74,75, 84, 85, 91, 104] explored the reasons people indicated a reluctance or unwillingness to perform CPR using open questions (rather than presenting possible reasons).

-

Unprompted reasons provided by those categorised as ‘unwilling’

-

TDF domain 4: beliefs about capability Concerns around capability were reported by 11% of unwilling high school students [104], and by 45% of those not willing to use an AED [91]. Concerns about physical capability in particular were reported by 11% of unwilling general public [74]. Low confidence was also reported (4%) [74] and 6–12% [51].

TDF domain 6: beliefs about consequences The reasons most commonly volunteered by those categorised as unwilling were concerns about to the risk to self: 56% of unwilling general public [74] with 24% [51], 35% [71] and 19% [74] concerned about the risk of infection in particular. Concerns about doing harm to the casualty were reported by 25% [71] and 23% [104]. Legal concerns were reported by 13% [71] and 19% [74] of people unwilling to provide CC and by 16% [71] and 4% [74] of those unwilling to provide mouth-to-mouth ventilation. CPR violating beliefs about death were also reported (4%) [71].

TDF domain 13: emotion Being too stressed (4%) [91] was also reported as a reason for unwillingness.

-

Prompted reasons

-

The reasons for not performing CPR most commonly proposed by researchers were: fear of doing harm (27 studies); concerns about infection (29 studies); legal concerns (24 studies); concerns about capability (26 studies) and concerns about mouth-to-mouth ventilation (10 studies). Averaging across the studies, the reasons endorsed by the largest proportion of unwilling participants were Lack of confidence (TDF Domain 4: Beliefs about capabilities), Fear of doing it wrong (TDF Domain 6: Beliefs about consequences) and Concerns about capability (TDF Domain 4: Beliefs about capabilities).

Discussion

We have conducted a comprehensive, high-quality, pre-registered systematic review of the psychological and behavioural factors relating to initiation of CPR. This provides a useful synthesis of the evidence to date and identifies promising avenues for intervention and further research. The prominence of two themes: the overwhelming emotion of the OHCA situation and concerns about physical capability in the more methodologically strong studies [58, 83] and evident across the various designs suggests these may be particularly important to address in order to increase CPR initiation.

Emotion of the situation

All five studies [47, 58, 67, 83] that analysed call-recordings involving actual CPR attempts identified the emotion of the situation as an important factor delaying initiation of CPR, as did studies of people who had witnessed OHCA [20, 94, 130].

In hypothetical studies, the expectation of high emotion was significantly associated with not being prepared to act [101] and identified as a likely barrier to CPR by high school students [32]. However, interestingly the potential impact of strong emotions was not frequently anticipated by those without experience of CPR (even when prompted) suggesting people may under-estimate the impact of emotion on their behaviour. Helping people to prepare for the unanticipated impact of strong emotions and providing strategies to perform CPR despite their emotional response might be helpful.

Concerns about capability

Concerns about physical capability were identified as a barrier to initiation in all five studies that analysed emergency call recordings [47, 58, 67, 83], identified in a survey of people who had witnesses an OHCA [20] and provided unprompted as an issue by 11% of the general public [74]. Further, those with good self-rated health were more likely to report being able to perform CPR than those with poor health [111]. Evidence also identified that feeling confident about one’s capability [119] and self-perceived capability [97, 117] are associated with increased willingness to perform CPR and conversely that a lack of confidence reduces willingness [101]. Concerns about capability were identified unprompted by 11% of students [104] and endorsed when prompted by up to 80% of participants. This triangulation of evidence from very different sources suggests concerns about capability as a key issue. Concerns may reflect actual physical limitations amongst potential rescuers but are also likely to reflect people’s beliefs about their capabilities; both are amenable to intervention but importantly will require very different approaches.

Predictors of CPR that have been formally tested

Studies which statistically tested the relationship between variables of interest and intention to perform CPR or actual behaviour were few, highlighting a need for more definitive studies to confirm posited relationships. Previous experience in performing [80, 113] or witnessing CPR [116] and self-perceived ability [97] were the variables most strongly associated with willingness suggesting interventions that improve perceptions of capability may be helpful.

Six studies found evidence to support predictors derived from behavioural theory such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour [137], highlighting the potential utility of an approach to intervention that is based on behavioural theory. Positive attitudes about CPR [92, 106, 131], perceived behavioural control [92, 131] and normative beliefs [92, 131] were significantly associated with intention to perform CPR and Magid (2019) [92] found the theory accounted for 51% of the variance in intention to perform CPR overall. These belief-based constructs are amenable to change and thus are promising targets for intervention. Resources such as the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy [138] and the Theory and Techniques resource (https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/) are available to help researchers and practitioners identify techniques to include in interventions based on their likely mode of action and their likely effectiveness to change the behaviour of interest (in this case initiation of CPR) in the required situation of OHCA.

Overall, it was notable how few papers explicitly discussed underlying theory and how multiple terms were used to refer to highly similar constructs (e.g. intention, willingness, readiness, prepared to act, capable in an emergency). Construct proliferation [139] and lack of precision in defining and labelling of constructs limits our collective ability to synthesise available evidence and to build a cumulative science [140]. This may lead to wasteful duplication of effort and hinder our ability to identify factors that increase initiation of CPR and, importantly, the factors that make initiation of CPR less likely. Greater attention to robust study design, explicit use of theory or at least consistent definitions of terms might bring us more quickly to our collective goal of increasing CPR initiation.

Limitations

This review is limited as we have only assessed published materials. There is thus the potential that publication bias has resulted in studies with negative findings being less likely to be identified [141]. We identified a preponderance of cross-sectional surveys using unvalidated measures with relatively little formal testing of posited ‘predictors’ meaning that it is difficult to draw robust and reliable conclusions from the literature.

Conclusion

Many psychological and behavioural factors associated with CPR initiation can be identified from the current literature with varying degrees of supporting evidence. Preparing people to manage strong emotions and increasing their perceptions of capability are likely important foci for interventions aiming to increase CPR initiation.

Greater use of theory and more robust study designs would strengthen knowledge in this area.

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018117438.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CPR :

-

Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation

- OHCA :

-

Out of hospital cardiac arrest

- EPHPP :

-

Effective public health practice project

- QARI:

-

Qualitative assessment and review instrument

- PRISMA :

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behaviour

- TDF:

-

Theoretical domains framework

References

Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1479–87.

Ong MEH, Do Shin S, De Souza NNA, Tanaka H, Nishiuchi T, Song KJ, et al. Outcomes f or out-of-hospital cardiac arrests across 7 countries in Asia: the Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS). Resuscitation. 2015;96:100–8.

Lindner TW, Soreide E, Nilsen OB, Torunn MW, Lossius HM. Good outcome in every fourth resuscitation attempt is achievable--an Utstein template report from the Stavanger region. Resuscitation. 2011;82(12):1508–13.

Perkins GD, Lockey AS, de Belder MA, Moore F, Weissberg P, Gray H. National initiatives to improve outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in England. London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and the British Association for Accident & Emergency Medicine; 2015.

Gräsner J-T, Wnent J, Herlitz J, Perkins GD, Lefering R, Tjelmeland I, et al. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe-results of the EuReCa TWO study. Resuscitation. 2020;148:218–26.

Graham R, McCoy MA, Schultz AM. Strategies to improve cardiac arrest survival: a time to act. Washington: National Academies Press; 2015.

Beck B, Bray J, Cameron P, Smith K, Walker T, Grantham H, et al. Regional variation in the characteristics, incidence and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia and New Zealand: results from the Aus-ROC Epistry. Resuscitation. 2018;126:49–57.

Scottish Government. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A strategy for Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2015.

British Heart Foundation. Consensus paper on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in England. 2014. https://www.resus.org.uk/publications/consensus-paper-on-out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest-in-england/; . Contract No.: 17/01/2018.

Welsh Government. In: Wales N, editor. Out of hospital cardiac arrest plan in; 2017.

Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J, Rosenqvist M, Hollenberg J, Nordberg P, et al. Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2307–15.

Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63-81.

Gräsner J-T, Lefering R, Koster RW, Masterson S, Böttiger BW, Herlitz J, et al. EuReCa ONE-27 nations, ONE Europe, ONE registry: A prospective one month analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in 27 countries in Europe. Resuscitation. 2016;105:188–95.

McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, Vellano K, Valderrama AL, Yoon PW, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance—cardiac arrest registry to enhance survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005–December 31, 2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2011;60(8):1–19.

Barnard EBG, Sandbach DD, Nicholls TL, Wilson AW, Ercole A. Prehospital determinants of successful resuscitation after traumatic and non-traumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(6):333–9.

Association AH. Our impact https://www.heart.org/en/impact-map2021 [cited 2021 26/02/21]. Available from: https://www.heart.org/en/impact-map.

Foundation BH. Government confirms plans to teach CPR in schools 2020 [Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2019/january/government-confirms-plans-to-teach-cpr-in-schools]. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Jama. 2013;310(13):1377–84.

Government S. OHCA data linkage statistics 2019 [Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-out-hospital-cardiac-arrest-data-linkage-project-2018-19-results/pages/5/].

Swor R, Khan I, Domeier R, Honeycutt L, Chu K, Compton S. CPR training and CPR performance: do CPR-trained bystanders perform CPR? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(6):596–601.

Soar J, Maconochie I, Wyckoff MH, Olasveengen TM, Singletary EM, Greif R, et al. 2019 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations: summary from the basic life support; advanced life support; pediatric life support; neonatal life support; education, implementation, and teams; and first aid task forces. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e826–e80.

Plant N, Taylor K. How best to teach CPR to schoolchildren: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):415–21.

Yeung J, Meeks R, Edelson D, Gao F, Soar J, Perkins GD. The use of CPR feedback/prompt devices during training and CPR performance: A systematic review. Resuscitation. 2009;80(7):743–51.

Greif R, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, Bray J, Breckwoldt J, Cheng A, et al. Education, implementation, and teams: 2020 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_1):S222–S83.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2011.

EPHPP. Effective Public Health Practice Project. (1998). Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html. 2009 7/2015. Available from: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Briggs J. Checklist for qualitative research. Adelaide: JoannBriggs Institute; 2017. [Available from: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-08/Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research.pdf].

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):18.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):1–18.

Holleman GA, Hooge IT, Kemner C, Hessels RS. The ‘real-world approach’and its problems: A critique of the term ecological validity. Front Psychol. 2020;11:721.

Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513.

Aaberg AM, Larsen CE, Rasmussen BS, Hansen CM, Larsen JM. Basic life support knowledge, self-reported skills and fears in Danish high school students and effect of a single 45-min training session run by junior doctors; a prospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2014;22:24.

Alhussein RM, Albarrak MM, Alrabiah AA, Aljerian NA, Bin Salleeh HM, Hersi AS, et al. Knowledge of non-healthcare individuals towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross-sectional study in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Int J Emerg Med. 2021;14(1):1–9.

Alshudukhi A, Alqahtani A, Alhumaid A, Alfakhri A, Aljerian NJIJCRLS. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of the general saudi population regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a survey. Int J Curr Res Life Sci. 2018;7(04):1699–704.

Anto-Ocrah M, Maxwell N, Cushman J, Acheampong E, Kodam R-S, Homan C, et al. Public knowledge and attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in Ghana, West Africa. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):1–12.

Axelsson A, Herlitz J, Ekström L, Holmberg S. Bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation out-of-hospital. A first description of the bystanders and their experiences. Resuscitation. 1996;33(1):3–11.

Axelsson A, Thoren A, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Attitudes of trained Swedish lay rescuers toward CPR performance in an emergency: a survey of 1012 recently trained CPR rescuers. Resuscitation. 2000;44:27-36.

Babić SB, Gregor; Peršolja, Melita. Laypersons’ awareness of cardiac arrest resuscitation procedures: cross-sectional study. Ošetrovateľstvo:Tteória, Výskum, Vzdelávanie. 2020; 10(2):[55–62]. Available from: https://www.osetrovatelstvo.eu/archiv/2020-rocnik-10/cislo-2/laypersons-awareness-of-cardiac-arrest-resuscitation-procedures-cross-sectional-study.

Becker TK, Gul SS, Cohen SA, Maciel CB, Baron-Lee J, Murphy TW, et al. Public perception towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(11):660–5.

Bin H, M AL, H AL, Alanazi A, Al o, Saleh. Community awareness about cardiopulmonary resuscitation among secondary school students in Riyadh. World J Med Sci 2013;8(3):186–189.

Birkun A, Kosova Y. Social attitude and willingness to attend cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and perform resuscitation in the Crimea. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(4):237–48.

Bohn A, Van Aken HK, Mollhoff T, Wienzek H, Kimmeyer P, Wild E, et al. Teaching resuscitation in schools: annual tuition by trained teachers is effective starting at age 10. A four-year prospective cohort study. Resuscitation. 2012;83(5):619–25.

Bouland AJ, Halliday MH, Comer AC, Levy MJ, Seaman KG, Lawner BJ. Evaluating barriers to bystander CPR among laypersons before and after compression-only CPR training. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(5):662–9.

Bray JE, Straney L, Smith K, Cartledge S, Case R, Bernard S, et al. Regions with low rates of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have Lower rates of CPR training in Victoria, Australia. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6):05.

Breckwoldt J, Schloesser S, Arntz HR. Perceptions of collapse and assessment of cardiac arrest by bystanders of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OOHCA). Resuscitation. 2009;80(10):1108–13.

Brinkrolf P, Metelmann B, Scharte C, Zarbock A, Hahnenkamp K, Bohn A. Bystander-witnessed cardiac arrest is associated with reported agonal breathing and leads to less frequent bystander CPR. Resuscitation. 2018;127:114–8.

Case R, Cartledge S, Siedenburg J, Smith K, Straney L, Barger B, et al. Identifying barriers to the provision of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in high-risk regions: A qualitative review of emergency calls. Resuscitation. 2018;129:43–7.

Chen M, Wang Y, Li X, Hou L, Wang Y, Liu J, et al. Public knowledge and attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in China. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3250485.

Cheng YC, Hu SC, Yen D, Kao WF, Lee CH. Targeted mass CPR training for families of cardiac patients - experience in Taipei city. Tzu Chi Med J. 1997;9(4):273–8.

Cheng-Yu C, Yi-Ming W, Shou-Chien H, Chan-Wei K, Chung-Hsien C. Effect of population-based training programs on bystander willingness to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Signa Vitae. 2016;12(1):63–9.

Cheskes L, Morrison LJ, Beaton D, Parsons J, Dainty KN. Are Canadians more willing to provide chest-compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)?—a nation-wide public survey. CJEM: Canadian. J Emerg Med. 2016;18(4):253–63.

Chew KS, Yazid MN, Kamarul BA, Rashidi A. Translating knowledge to attitude: a survey on the perception of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation among dental students in Universiti Sains Malaysia and school teachers in Kota Bharu. Kelantan Med J Malaysia. 2009;64(3):205–9.

Chew KS, Ahmad Razali S, Wong SSL, Azizul A, Ismail NF, Robert SJKCA, et al. The influence of past experiences on future willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int J Emerg Med. 2019;12(1):1–7.

Cho GC, Sohn YD, Kang KH, Lee WW, Lim KS, Kim W, et al. The effect of basic life support education on laypersons' willingness in performing bystander hands only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(6):691–4.

Compton S, Swor RA, Dunne R, Welch RD, Zalenski RJ. Urban public school teachers' attitudes and perceptions of the effectiveness of CPR and automated external defibrillators. Am J Health Educ. 2003;34(4):186–92.

Coons SJ, Guy MC. Performing bystander CPR for sudden cardiac arrest: behavioral intentions among the general adult population in Arizona. Resuscitation. 2009;80:334-40.

Cu J, Phan P, O'Leary FM. Knowledge and attitude towards paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation among the carers of patients attending the Emergency Department of the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21(5):401–6.

Dami F, Carron PN, Praz L, Fuchs V, Yersin B. Why bystanders decline telephone cardiac resuscitation advice. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(9):1012–5.

De Smedt L, Depuydt C, Vekeman E, De Paepe P, Monsieurs KG, Valcke M, et al. Awareness and willingness to perform CPR: a survey amongst Flemish schoolchildren, teachers and principals. Acta Clin Belgica: Int J Clin Lab Med. 2018;74(5):1–20.

Dobbie F, MacKintosh AM, Clegg G, Stirzaker R, Bauld L. Attitudes towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: results from a cross-sectional general population survey. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193391.

Donohoe RT, Haefeli K, Moore F. Public perceptions and experiences of myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and CPR in London. Resuscitation. 2006;71(1):70–9.

Dracup K, Moser DK, Guzy PM, Taylor SE, Marsden C. Is cardiopulmonary resuscitation training deleterious for family members of cardiac patients? Am J Public Health. 1994;84(1):116–8.

Dwyer T. Psychological factors inhibit family members' confidence to initiate CPR. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(2):157–61.

Enami M, Takei Y, Goto Y, Ohta K, Inaba H. The effects of the new CPR guideline on attitude toward basic life support in Japan. Resuscitation. 2010;81(5):562–7.

Fratta KA, Bouland AJ, Vesselinov R, Levy MJ, Seaman KG, Lawner BJ, et al. Evaluating barriers to community CPR education. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(3):603–9.

Han KS, Lee JS, Kim SJ, Lee SW. Targeted cardiopulmonary resuscitation training focused on the family members of high-risk patients at a regional medical center: A comparison between family members of high-risk and no-risk patients. Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;24(3):224–33.

Hauff SR, Rea TD, Culley LL, Kerry F, Becker L, Eisenberg MS. Factors impeding dispatcher-assisted telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):731–7.

Hawkes CA, Brown TP, Booth S, Fothergill RT, Siriwardena N, Zakaria S, et al. Attitudes to cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillator use: a survey of UK adults in 2017. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(7):e008267.

Hollenberg J, Claesson A, Ringh M, Nordberg P, Hasselqvist-Ax I, Nord A. Effects of native language on CPR skills and willingness to intervene in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after film-based basic life support training: a subgroup analysis of a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e025531.

Huang Q, Hu C, Mao J. Are Chinese students willing to learn and perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation? J Emerg Med. 2016;51(6):712–20.

Hubble MW, Bachman M, Price R, Martin N, Huie D. Willingness of high school students to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2003;7(2):219–24.

Hung MSY, Chow MCM, Chu TTW, Wong PP, Nam WY, Chan VLK, et al. College students’ knowledge and attitudes toward bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A cross-sectional survey. Cogent Medicine. 2017;4(1) no pagination:1334408.

Iserbyt P. The effect of Basic Life Support (BLS) education on secondary school students’ willingness to and reasons not to perform BLS in real life. Acta Cardiol. 2016;71(5):519–26.

Jelinek GA, Gennat H, Celenza T, O'Brien D, Jacobs I, Lynch D. Community attitudes towards performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Western Australia. Resuscitation. 2001;51(3):239–46.

Johnston TC, Clark MJ, Dingle GA, FitzGerald G. Factors influencing Queenslanders’ willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;56:67-75.

Kandakai TL, King KA. Perceived self-efficacy in performing lifesaving skills: an assessment of the American red Cross's responding to emergencies course. J Health Educ. 1999;30(4):235–41.

Kanstad BK, Nilsen SA, Fredriksen K. CPR knowledge and attitude to performing bystander CPR among secondary school students in Norway. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1053-9.

Karuthan SR, binti Firdaus PJF, Angampun AD-AG, Chai XJ, Sagan CD, Ramachandran M, et al. Knowledge of and willingness to perform hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation among college students in Malaysia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(51):e18466.

Kua PHJ, White AE, Ng WY, Fook-Chong S, Ng EKX, Ng YY, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of Singapore schoolchildren learning cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator skills. Singapore Med J. 2018;59(9):487–99.

Kuramoto N, Morimoto T, Kubota Y, Maeda Y, Seki S, Takada K, et al. Public perception of and willingness to perform bystander CPR in Japan. Resuscitation. 2008;79(3):475–81.

Lam K-K, Lau F-L, Chan W-K, Wong W-N. Effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on bystander willingness to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)–is compression–only preferred to standard CPR? Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22(4):325–9.

Lee MJ, Hwang SO, Cha KC, Cho GC, Yang HJ, Rho TH. Influence of nationwide policy on citizens' awareness and willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):889–94.

Lerner EB, Sayre MR, Brice JH, White LJ, Santin AJ, Billittier AJ, et al. Cardiac arrest patients rarely receive chest compressions before ambulance arrival despite the availability of pre-arrival CPR instructions. Resuscitation. 2008;77(1):51–6.

Lester C, Donnelly P, Weston C. Is peer tutoring beneficial in the context of school resuscitation training? Health Educ Res. 1997;12(3):347–54.

Lester C, Donnelly P, Assar D. Community life support training: does it attract the right people? Public Health. 1997;111(5):293–6.

Lester C, Donnelly P, Assar D. Lay CPR trainees: retraining, confidence and willingness to attempt resuscitation 4 years after training. Resuscitation. 2000;45(2):77–82.

Liaw SY, Chew KS, Zulkarnain A, Wong SSL, Singmamae N, Kaushal DN, et al. Improving perception and confidence towards bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and public access automated external defibrillator program: how does training program help? Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):1–7.

Locke CJ, Berg RA, Sanders AB, Davis MF, Milander MM, Kern KB, et al. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Concerns about mouth-to-mouth contact. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(9):938–43.

Lu C, Jin Y-h, Shi X-t, Ma W-j, Wang Y-y, Wang W, et al. Factors influencing Chinese university students’ willingness to performing bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int Emerg Nurs. 2017;32:3–8.

Lynch B, Einspruch EL. With or without an instructor, brief exposure to CPR training produces significant attitude change. Resuscitation. 2010;81(5):568–75.

Maes F, Marchandise S, Boileau L, Polain L, de Waroux JB, Scavee C. Evaluation of a new semiautomated external defibrillator technology: a live cases video recording study. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(6):481–5.

Magid KH, Heard D, Sasson C. Addressing gaps in cardiopulmonary resuscitation education: training middle school students in hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Sch Health. 2018;88(7):524–30.

Mathiesen WT, Bjørshol CA, Høyland S, Braut GS, Søreide E. Exploring how lay rescuers overcome barriers to provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A qualitative study. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(1):27–32.

Mausz J, Snobelen P, Tavares W. “Please. Don't. Die.”: A grounded theory study of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(2):e004035-e.

McCormack AP, Damon SK, Eisenberg MS. Disagreeable physical characteristics affecting bystander CPR. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(3):283–5.

Mecrow TS, Rahman A, Mashreky SR, Rahman F, Nusrat N, Scarr J, et al. Willingness to administer mouth-to-mouth ventilation in a first response program in rural Bangladesh. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015;15(1):1–5.

Meischke HW, Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Rowe SM. Intentions to use an automated external defibrillator during a cardiac emergency among a group of seniors trained in its operation. Heart Lung. 2002;31(1):25–9.

Moller TP, Hansen CM, Fjordholt M, Pedersen BD, Ostergaard D, Lippert FK. Debriefing bystanders of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is valuable. Resuscitation. 2014;85(11):1504–11.

Nielsen AM, Isbye DL, Lippert FK, Rasmussen LS. Can mass education and a television campaign change the attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a rural community? Scandinavian journal of trauma. Resuscit Emerg Med. 2013;21(1):39.

Nishiyama C, Sato R, Baba M, Kuroki H, Kawamura T, Kiguchi T, et al. Actual resuscitation actions after the training of chest compression-only CPR and AED use among new university students. Resuscitation. 2019;141:63–8.

Nolan RP, Wilson E, Shuster M, Rowe BH, Stewart D, Zambon S. Readiness to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an emerging strategy against sudden cardiac death. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(4):546–51.

Nord A, Svensson L, Hult H, Kreitz-Sandberg S, Nilsson L. Effect of mobile application-based versus DVD-based CPR training on students’ practical CPR skills and willingness to act: a cluster randomised study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010717-e.

Nord A, Hult H, Kreitz-Sandberg S, Herlitz J, Svensson L, Nilsson L. Effect of two additional interventions, test and reflection, added to standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation training on seventh grade students' practical skills and willingness to act: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e014230-e.

Omi W, Taniguchi T, Kaburaki T, Okajima M, Takamura M, Noda T, et al. The attitudes of Japanese high school students toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2008;78:82-7.

Onan A, Turan S, Elcin M, Erbil B, Bulut ŞÇ. The effectiveness of traditional basic life support training and alternative technology-enhanced methods in high schools, vol. 1024907918782239; 2018.

Parnell M, Pearson J, Galletly D, Larsen P. Knowledge of and attitudes towards resuscitation in New Zealand high-school students. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(12):899–902.

Pei-Chuan Huang E, Chiang WC, Hsieh MJ, Wang HC, Yang CW, Lu TC, et al. Public knowledge, attitudes and willingness regarding bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A nationwide survey in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;118(2):72-81.

Platz E, Scheatzle MD, Pepe PE, Dearwater SR. Attitudes towards CPR training and performance in family members of patients with heart disease. Resuscitation. 2000;47(3):273–80.

Rankin T, Holmes L, Vance L, Crehan T, Mills B. Recent high school graduates support mandatory cardiopulmonary resuscitation education in Australian high schools. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44(3):215–8.

Riou M, Ball S, Whiteside A, Gallant S, Morgan A, Bailey P, et al. Caller resistance to perform cardio-pulmonary resuscitation in emergency calls for cardiac arrest. Soc Sci Med. 2020;256:113045.

Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Hong SO, Kim YT, Cho S-I. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation training experience and self-efficacy of age and gender group: a nationwide community survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1331–7.

Rowe BH, Shuster M, Zambon S, Wilson E, Stewart D, Nolan RP, et al. Preparation, attitudes and behaviour in nonhospital cardiac emergencies: evaluating a community's readiness to act. Can J Cardiol. 1998;14(3):371–7.

Sasaki M, Ishikawa H, Kiuchi T, Sakamoto T, Marukawa S. Factors affecting layperson confidence in performing resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Japan. Acute Med Surg. 2015;2(3):183–9.

Sasson C, Haukoos JS, Bond C, Rabe M, Colbert SH, King R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to learning and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in neighborhoods with low bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation prevalence and high rates of cardiac arrest in Columbus. OH Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(5):550–8.

Sasson C, Haukoos JS, Ben-Youssef L, Ramirez L, Bull S, Eigel B, et al. Barriers to calling 911 and learning and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation for residents of primarily Latino, high-risk neighborhoods in Denver, Colorado. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(5):545–52. e2.

Schmid KM, Mould-Millman NK, Hammes A, Kroehl M, Garcia RQ, McDermott MU, et al. Barriers and facilitators to community CPR education in San Jose, Costa Rica. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(5):509–15.

Schmitz B, Schuffelen P, Kreijns K, Klemke R, Specht M. Putting yourself in someone else's shoes: the impact of a location-based, collaborative role-playing game on behaviour. Comput Educ. 2015;85:160–9.

Schneider L, Sterz F, Haugk M, Eisenburger P, Scheinecker W, Kliegel A, et al. CPR courses and semi-automatic defibrillators - life saving in cardiac arrest? Resuscitation. 2004;63(3):295–303.

Shams A, Raad M, Chams N, Chams S, Bachir R, El Sayed MJ. Community involvement in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A cross-sectional study assessing cardiopulmonary resuscitation awareness and barriers among the Lebanese youth. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(43):e5091.

Shibata K, Taniguchi T, Yoshida M, Yamamoto K. Obstacles to bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan. Resuscitation. 2000;44:187-93.

Sipsma K, Stubbs BA, Plorde M. Training rates and willingness to perform CPR in King County, Washington: a community survey. Resuscitation. 2011;82(5):564–7.

Skora J, Riegel B. Thoughts, feelings, and motivations of bystanders who attempt to resuscitate a stranger: A pilot study. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(6):408–16.

Smith KL, Cameron PA, Meyer AD, McNeil JJ. Is the public equipped to act in out of hospital cardiac emergencies? Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):85–7.

Sneath JZ, Lacey R. Marketing defibrillation training programs and bystander intervention support. Health Mark Q. 2009;26(2):87–97.

So KY, Ko HF, Tsui CSY, Yeung CY, Chu YC, Lai VKW, et al. Brief compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator course for secondary school students: a multischool feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e040469.

Swor R, Grace H, McGovern H, Weiner M, Walton E. Cardiac arrests in schools: assessing use of automated external defibrillators (AED) on school campuses. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):426–9.

Tang H-m, Wu X, Jin Y, Jin Y-q, Wang Z-j, Luo J-y, et al. Shorter training intervals increase high school students’ awareness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a questionnaire study. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(1):0300060519897692.

Taniguchi T, Omi W, Inaba H. Attitudes toward the performance of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan. Resuscitation. 2007;75(1):82–7.

Taniguchi T, Sato K, Fujita T, Okajima M, Takamura M. Attitudes to bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan in 2010. Circ J. 2012;76(5):1130–5.

Thorén A-N, Danielson E, Herlitz J, Axelsson AB. Spouses' experiences of a cardiac arrest at home: an interview study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(3):161–7.

Vaillancourt C, Kasaboski A, Charette M, Islam R, Osmond M, Wells GA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to CPR training and performing CPR in an older population most likely to witness cardiac arrest: a national survey. Resuscitation. 2013;84(12):1747–52.

Vetter VL, Haley DM, Dugan NP, Iyer VR, Shults J. Innovative cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator programs in schools: results from the student program for olympic resuscitation training in schools (SPORTS) study. Resuscitation. 2016;104:46–52.

Wilks J, Ma AWW, Vyas L, Wong KL, Tou AYL. CPR knowledge and attitudes among high school students aged 15-16 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):3–13.

Winkelman JL, Fischbach R, Spinello EF. Assessing CPR training: the willingness of teaching credential candidates to provide CPR in a school setting. Educ Health. 2009;22(3):81.

Zinckernagel L, Malta Hansen C, Rod MH, Folke F, Torp-Pedersen C, Tjornhoj-Thomsen T. What are the barriers to implementation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in secondary schools? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010481.

Breckwoldt J, Lingemann C, Wagner P. Resuscitation training for lay persons in first aid courses: transfer of knowledge, skills and attitude. [German]. Anaesthesist. 2016;65(1):22–9.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81-95.

Shaffer JA, DeGeest D, Li A. Tackling the problem of construct proliferation: A guide to assessing the discriminant validity of conceptually related constructs. Organ Res Methods. 2016;19(1):80–110.

Michie S, Johnston M. Theories and techniques of behaviour change: developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6(1):1–6.

Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie R, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. Bmj. 2000;320(7249):1574–7.

Farquharson B, Dixon D, Williams B. The psychological and behavioural factors associated with laypeople initiating CPR for our-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Euro J Cardio Nurs. 2021;20(supp 1):zvab060-045.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following: Anna Temp who helped with registering the review, conducting the initial searches, and obtaining manuscripts. Sheena Moffat, Librarian at Edinburgh Napier University who provided invaluable advice on database searching. The Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government who provided funding for the review (CGA/18/11).

An earlier draft of this review was presented at Euroheartcare conference 2021. Abstract published in European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing [142].

Funding

The Chief Scientist Office (Scotland) funded the study (CGA/18/11) but had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Barbara Farquharson (BF) created the original concept, methodology, obtained funding for the review, conducted searches, performed screening and data extraction, supervised others on the project and wrote the original draft manuscript. Diane Dixon (DD) created the original concept, methodology, obtained funding for the review, conducted searches, performed screening and data extraction, supervised others on the project and contributed to the final manuscript. Brian Williams (BW) created the original concept, methodology, obtained funding for the review and contributed to the final manuscript. Claire Torrens (CT) performed screening and data extraction and contributed to the final manuscript. Melanie Philpott (MP) contributed to the final manuscript. Henriette Laidlaw (HL) helped plan data extraction and contributed to the final manuscript. Siobhan McDermott (SM) performed data extraction and contributed to the final manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (Systematic Review).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (Systematic Review).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Farquharson, B., Dixon, D., Williams, B. et al. The psychological and behavioural factors associated with laypeople initiating CPR for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02904-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02904-2