Abstract

Background

Recent studies have focused on the potential role of epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) in the development of coronary artery disease (CAD). ABCA1 and ABCG1 transporters regulate cell cholesterol content and reverse cholesterol transport. We aimed to determine whether DNA methylation and mRNA levels of the ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes in EAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) were associated with CAD.

Methods

Paired EAT and SAT samples were collected from 82 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery either for coronary artery bypass grafting (CAD group, N = 66) or valve surgery (NCAD group, N = 16). ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT samples were analyzed using real time polymerase chain reaction, ABCA1 protein levels in EAT samples were assessed by western blotting. ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation analysis was performed in 24 samples from the CAD group and 9 samples from the NCAD group via pyrosequencing.

Results

DNA methylation levels in the ABCA1 promoter and ABCG1 cg27243685 and cg06500161 CpG sites were higher in EAT samples from patients with CAD compared with NCAD (21.92% vs 10.81%, p = 0.003; 71.51% vs 68.42%, p = 0.024; 46.11% vs 37.79%, p = 0.016, respectively). In patients with CAD, ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation levels were higher in EAT than in SAT samples (p < 0.05). ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT samples were reduced in the subgroup of patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease compared with the NCAD group (p = 0.024). ABCA1 protein levels in EAT samples tended to be lower in CAD patients than in the NCAD group (p = 0.053). DNA methylation levels at the ABCG1 cg27243685 site positively correlated with plasma triglyceride concentration (r = 0.510, p = 0.008), body mass index (r = 0.556, p = 0.013) and waist-to-hip ratio (r = 0.504, p = 0.012) in SAT samples.

Conclusion

CAD is associated with ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA hypermethylation in EAT. CAD with concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease is accompanied by decreased ABCA1 gene expression in EAT. DNA methylation levels at the ABCG1 cg27243685 locus in SAT are associated with hypertriglyceridemia and obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity has been linked with cardiometabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia and hypertension as well as cardiovascular diseases [1]. Total body adiposity correlates with the amount of epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), a specific visceral fat accumulation around the myocardium in the proximity to the coronary arteries [2]. In recent years, an association between EAT thickness and coronary artery disease (CAD) has been reported, and EAT has been proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of CAD [3,4,5,6]. Adipose tissue is considered to be an endocrine organ producing adipocytokines that might modulate atherosclerosis progression [7,8,9]. Several lines of evidence suggest that adipose tissue reverse cholesterol transport impairment leads to adipocyte cholesterol imbalance and dysfunction [10,11,12]. It is worth noting that reverse cholesterol transport could be disrupted in EAT of CAD patients [9].

Cholesterol efflux from adipocytes is mediated by the cholesterol transport proteins ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) and ATP-binding cassette G1 (ABCG1). ABCA1 regulates the formation of nascent high-density lipoprotein (HDL) via cholesterol efflux to lipid free apolipoprotein A-1, whereas ABCG1 mediates cholesterol transport to the HDL fraction [13]. Adipocyte Abca1 deficiency is associated with HDL reduction in animal models, suggesting that adipose tissue contributes to HDL formation as well [14, 15]. ABCA1 and ABCG1 gene expression in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue has been shown to be dysregulated in obesity and during metabolic syndrome development [16,17,18,19]. However, whether ABCA1 and ABCG1 activity plays a role in EAT of CAD patients remains unknown.

Recent findings suggest that DNA methylation changes are related to the development and progression of a group of human diseases including atherosclerosis. Previously, we and others demonstrated differences in genome-wide DNA methylation patterns between atherosclerotic plaques and normal arteries [20,21,22]. Differential methylation within the ABCA1 and ABCG1 regulatory regions in leukocytes has been previously shown to contribute to the interindividual variability in plasma HDL concentrations and was associated with atherosclerosis-related diseases [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Taken together, the data indicate a key role for DNA methylation of the ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes in the development of diseases associated with impaired lipid metabolism [28]. We hypothesized that ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation patterns may be altered in EAT of CAD patients.

The aim of this study was to investigate the ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation status and gene expression in paired samples of EAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) from patients with CAD.

Methods

Patients

A total of 82 patients diagnosed with CAD and heart valve disease who underwent cardiac surgery from September 2016 to April 2017 were enrolled in this study.

Coronary angiography was performed in all participants to identify coronary atherosclerosis, and patients were divided into two groups: CAD patients (n = 66) or non-CAD subjects (NCAD; n = 16) as a control group. Inclusion to the CAD group was determined via coronary angiography and included patients with 1-2-3-vessel coronary obstruction, who underwent further coronary bypass grafting surgery. The NCAD group included patients undergoing open-heart surgery for valvular replacement without stenosis in the coronary artery lumen. Clinical characteristics, including demographic data, adiposity parameters [body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio], lipid profiles, smoking and medical history were obtained from the hospital records. The main clinical characteristics of the studied groups are presented in Table 1. The exclusion criteria were as follows: cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver or renal failure, connective tissue diseases, acute rheumatic fever, infective endocarditis, hypo/hyperthyroidism, brain diseases, alcohol or drug abuse and acute cerebrovascular accident. EAT thickness was measured by echocardiography using the GE VIVID 7 Dimension cardiovascular ultrasound system, in front of the right ventricle wall from the parasternal long axis view.

The study protocol is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of Pavlov First Saint-Petersburg State Medical University, Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation. Written informed consent was given by each participant.

Adipose tissue samples

Paired EAT and SAT samples were obtained during cardiac surgery from approximately the same location in all patients. EAT was obtained near the right coronary artery ostium and SAT from the area of chest incision. The tissue samples (average 0.1 g) were separated from any attached connective tissue and blood vessels and were stored at -80ºC for further analysis.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini columns (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were assessed by calculating the ratio of optical density at 260 and 280 nm (OD 260/280), and the integrity of RNA was reflected by the presence of 18S and 28S ribosomal bands in electrophoresis through 1% agarose gels. A total of 1 µg of RNA from each biopsy was reverse transcribed with RevertAid cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the instruction manual. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was conducted using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA). Primers and probes for TaqMan RT-PCR of the ABCA1 and ABCG1 and the reference genes are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Each reaction contained 1 µL of cDNA, 0.5 µL of each primer (10 µmol/L), 0.8 µL of TaqMan probes (10 µmol/L), 8 µL of deionized water and 10 µL of Master Mix (AlcorBio, Russia). Amplification was performed as follows: 3 min at 95 °C, then 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 58 °C, 15 s at 72 °C. Threshold cycle (Ct) values were obtained and relative gene expression was normalized to two reference genes (RPLP0 and ACTB), as previously described [19].

DNA methylation analysis

DNA was isolated from ~ 50 mg of EAT and SAT samples using standard proteinase K digestion and phenol–chloroform extraction method. DNA quality and quantity were analyzed using the NanoDrop 8000 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA). Maximum 24 samples from the CAD group and 9 samples from the NCAD group for each type of adipose tissue were available for methylation analysis according to sufficient amount of material and DNA quality tests. Subsequently, 500 ng of genomic DNA with a 260/280 nm extinction ratio > 1.8 were treated with bisulfite using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research Inc., USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA methylation assay for locus 1 (cg27243685) of the ABCG1 gene was designed with the MethPrimer Software [29]. Analysis of the remaining CpG sites was performed according to the previous studies [30, 31]. The genomic location and primer sequences are presented in Table 2. For PCR, 40–50 ng of bisulfite-converted DNA was amplified using 2 U Hot Start Taq DNA polymerase (AlcorBio, Russia) and 0.2 μM forward and biotinylated reverse primers in a 50-μl reaction volume including 0.2 mM dNTPs and 2 mM MgCl2. PCR conditions were: 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 7 min. For DNA methylation levels, the percentage of 5-methylcytosine at individual CpG sites of the ABCA1 and ABCG1 was assessed by pyrosequencing using PyroMark Q24 (Qiagen Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotin-labeled, single-stranded amplicons were retrieved and subjected to pyrosequencing using 0.3 μM sequencing primer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The percentage of methylation for each of the CpG sites within the target sequence was calculated using PyroQ CpG Software (Qiagen Inc.). Non-CpG cytosine residues were used as built-in controls to verify bisulfite conversion. Each sample was tested in two replicates and their average was used in the statistical analysis.

ABCA1 western blotting

Tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar, and the powder was homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing 50 mMTris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mMNaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland). The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the fraction below the lipid portion on the top was carefully aspirated into a new tube. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce, USA). A mass of 5 µg protein per lane was separated using 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA) and pre-incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS. The blots were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-ABCA1 (1:1000; ab7360, Abcam, United Kingdom) and polyclonal rabbit anti-β-actin (1:5000; ab8227, Abcam, United Kingdom) diluted in 1% skim milk in PBST (0.05% Tween 20) to prevent non-specific binding and followed by anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000; ab6721, Abcam, United Kingdom). Proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, United Kingdom).

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Depending on the distribution, data are presented either as the mean ± SD or as the median and min–max range. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages (%). Mean values were compared using t-tests, whereas non-parametric data were compared using Mann–Whitney’s U-test (between the CAD and NCAD groups). Differences between DNA methylation and mRNA levels in EAT and SAT were assessed using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Pairwise comparisons were Holm-Bonferroni corrected for four comparisons (two paired, two unpaired). Categorical variables were analyzed by Fisher's exact test. Spearman correlation testing was performed between methylation levels, mRNA and clinical and biochemical markers. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and in R statistical computing environment (the R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Results with a p value < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In this study, we evaluated the association of ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation and gene expression in EAT and SAT with CAD along with CAD risk determinants: adiposity parameters (BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio), lipid profiles and smoking status. The clinical characteristics of CAD patients and NCAD controls are shown in Table 1. Compared with the NCAD group, the CAD group was more likely to be overweight or obese, demonstrating slightly higher plasma triglyceride level, but without significant differences in the remaining lipid parameters.

The ABCA1 promoter region and two loci near cg06500161 and cg27243685 CpG sites in ABCG1 were selected for DNA methylation analysis because of their association with gene expression, lipid levels and cardiometabolic complications from several previous studies [23,24,25,26,27,28, 32,33,34,35,36,37]. The locations of the analyzed loci are shown in Additional file 2: Fig. S1. Methylation analysis included five CpG sites in the ABCA1 promoter region (including cg14019050), as well as three and two CpG sites in introns 1 and 2 of the ABCG1 gene, respectively (including the well-studied cg27243685 and cg06500161 sites) (Table 2). The differences for all CpG sites are provided in Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3.

Hypermethylation at all the analyzed loci in EAT samples was associated with CAD. Indeed, DNA methylation levels at the ABCA1 promoter region in EAT were 1.8-fold higher in patients with CAD compared with the NCAD group [21.92 (10.29–36.93) % vs 10.81 (7.12–18.74) %, p = 0.003; Fig. 1A]. Differences were significant for all five CpG sites when analyzed separately (Additional file 2: Table S2). ABCA1 promoter methylation levels in SAT did not differ between the CAD and the NCAD groups (Fig. 1A; Additional file 3: Table S2).

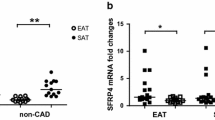

A Mean ABCA1 DNA methylation levels in EAT and SAT; B ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT samples from the CAD and NCAD groups; C ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT samples from the subgroup of patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease compared to the NCAD group; D ABCA1 protein levels in EAT samples from the CAD and NCAD groups and representative western blot. The origin bands of WB are presented in Additional file 5. Note: The CAD+ subgroup includes patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease

ABCG1 methylation levels at both studied loci in EAT were higher in CAD patients compared with the NCAD group. Specifically, the mean ABCG1 methylation levels at locus 1 in EAT were 71.15 (61.70–81.33) % in the CAD group and 65.66 (49.39–71.60) % in the NCAD group (p = 0.018). Differences were significant for all three CpG sites (Additional file 4: Table S3), including cg27243685 [71.51 (63.97–83.10) % vs 68.42 (51.56–70.88) %, p = 0.024; Fig. 2A]. The mean ABCG1 methylation levels at locus 2 in EAT were 53.57 (42.17–63.70) % in the CAD group and 43.16 (33.78–54.32) % in the NCAD group (p = 0.004). Differences were significant for both CpG sites (Additional file 4: Table S3), including cg06500161 [46.11 (33.04–59.76) % vs 37.79 (25.33–46.00) %, p = 0.016; Fig. 2B].

A ABCG1 cg06500161 locus methylation levels in EAT and SAT; B ABCG1 cg27243685 locus methylation levels in EAT and SAT; C ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT samples from the CAD and NCAD groups; D ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT samples from the subgroup of patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease compared to the NCAD group. Note: The CAD+ subgroup includes patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease

Regarding DNA methylation at ABCG1 locus 1 in SAT, there were no statistically significant differences for cg27243685, neither when analyzed separately, nor for mean DNA methylation levels (Additional file 4: Table S3). As for ABCG1 locus 2, the mean DNA methylation levels were slightly higher in the CAD group [43.65 (33.38–68.73) % vs 39.70 (28.06–42.31) %, p = 0.020]. Mean methylation levels were also higher at each CpG site, including cg06500161 [36.17 (25.87–68.55) % vs 31.68 (19.82–34.93) %, p = 0.048; Fig. 2B].

ABCA1 protein levels in EAT had a tendency to be lower in the CAD group (Fig. 1D; p = 0.053) while mRNA levels did not differ (Fig. 1B). In addition, ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT were reduced in the subgroup of patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease (i.e. proven multifocal atherosclerosis) compared with the NCAD group (Fig. 1C). ABCA1 mRNA levels in SAT also tended to be reduced in this subgroup, although the difference was not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. There were no differences in ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT between the CAD and NCAD groups (Fig. 2C). We did not analyze ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation levels in the subgroup of patients with CAD and concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease separately, as only three samples from this subgroup were available for DNA methylation analysis. We did not find any significant association between DNA methylation level at each investigated site and corresponding gene’s mRNA levels which may be a consequence of limited sample size available for DNA methylation analysis.

ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation and gene expression levels were analyzed according to smoking history, considering smoking during the time of the study, as well as smoking for a long period but quitting smoking prior to the study (ex-smokers). ABCA1 mRNA levels in SAT were reduced in combined group of smokers and ex-smokers [1.40 (0.16–8.42) vs 4.76 (0.13–14.07), p = 0.030; Additional file 6: Fig. S2] compared with patients who never smoked, indicating that mRNA levels did not increase after giving up smoking. DNA methylation levels were not associated with smoking status in this study.

Correlation analysis of ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation and gene expression levels with plasma lipids and adiposity markers was carried out. DNA methylation levels of ABCA1 in EAT and SAT, as well as ABCG1 in EAT did not correlated with lipid concentrations or anthropometric parameters. As for ABCG1 DNA methylation in SAT, there was a positive correlation between methylation levels at locus 1 and plasma triglycerides (r = 0.510, p = 0.008 for cg27243685; r = 0.441, p = 0.024 for mean DNA methylation levels at the locus), BMI (r = 0.556, p = 0.013 for cg27243685; r = 0.534, p = 0.018 for mean DNA methylation levels at the locus) and waist-to-hip ratio (r = 0.504, p = 0.012 for cg27243685; r = 0.419, p = 0.041 for mean DNA methylation levels at the locus) (Fig. 3). None of the measured parameters (ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation or mRNA levels) correlated with EAT thickness.

It should be noted that ABCG1 locus 1 and locus 2 mean methylation levels positively correlated with each other (r = 0.629, p = 0.000; r = 0.577, p = 0.002, for EAT and SAT accordingly). The correlation analysis for all CpG sites within analyzed loci is shown in Additional file 7: Fig. S3. Methylation levels in CpGs sites within the same locus showed a strong positive correlation.

Discussion

The study is the first to show that hypermethylation in the ABCA1 promoter region and ABCG1 CpG sites cg06500161 and cg27243685 in EAT is associated with CAD. We also demonstrated that ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT were reduced in CAD patients with concomitant carotid artery disease or peripheral artery disease, demonstrating a possible association of ABCA1 expression in EAT with severe multifocal atherosclerosis. As ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT in the CAD group were very variable, it could not be excluded that some remaining CAD patients could also have asymptomatic plaques in other vascular areas. In addition to revealing differences in ABCA1 mRNA levels and epigenetic changes in EAT between CAD patients and NCAD patients, we also assessed ABCA1 protein levels in EAT samples from both groups. ABCA1 protein levels in EAT tended to be decreased in the CAD group compared with NCAD patients. These data indicate that the process of reverse cholesterol transport may be impaired in EAT of CAD patients. It has previously been demonstrated that reverse cholesterol transport from EAT in CAD patients can be disrupted also due to decreased secretion of apolipoprotein A1, a known ligand for ABCA1 [9]. This suggests that normal EAT is active for reverse cholesterol transport, and hypermethylation of key cholesterol transport genes, including ABCA1 and ABCG1, may play a role in coronary atherosclerosis.

The majority of previous studies have investigated DNA methylation levels within ABCA1 and ABCG1 only in blood leukocytes. These studies have shown that DNA methylation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 was associated with a significant increase in the risk of atherosclerosis development and cardiovascular complications [23,24,25,26,27,28, 30, 38]. DNA methylation in the ABCA1 promoter region is associated with prior history of CAD in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia [30]. Blood DNA methylation levels in ABCG1 (cg06500161) are higher in subjects with previous hospitalized myocardial infarction compared with healthy controls [28]. ABCG1 hypermethylation at the cg02494239 is associated with carotid intima media thickness and ischemic stroke [27]. Atherosclerosis is one of the primary causes of ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction and is characterized by the formation of atherosclerotic lesions, and the intima media thickness of the carotid artery is a subclinical stage of atherosclerosis [39]. Therefore, DNA methylation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 could be involved in atherosclerosis development.

The most probable mechanism underlying how ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation could contributes to the progression of atherosclerotic plaques could involve reduced gene expression and subsequent reduction of macrophage cholesterol efflux [13, 24, 40,41,42]. In previous studies, ABCG1 has been shown to be hypermethylated and downregulated in blood monocytes/macrophages of CAD patients [24, 41, 43]. Furthermore, ABCA1 mRNA levels are upregulated in macrophages, while protein levels are decreased [44, 45]. As adipose tissue is a complex tissue composed of different cell subsets, including macrophages, it may be hypothesized that EAT macrophages are critical for atherosclerotic plaques formation in the nearby coronary artery pool. It is important to mention that adiposity is associated with macrophage infiltration in adipose tissues, and it has been shown that ABCG1 DNA methylation and gene expression could be affected by obesity [18, 46, 47].

Previous studies have demonstrated an inverse correlation between blood ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation and HDL levels [26, 30, 36, 37]. In this study, there was no association between ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation in adipose tissue and plasma cholesterol or HDL levels. However, ABCG1 cg27243685 methylation in SAT was associated with higher plasma triglyceride concentration and positively correlated with BMI and waist-to-hip ratio. Thus, ABCG1 expression in SAT could be influenced by DNA methylation and associated with abdominal obesity. A recent study has also shown that the correlation between BMI and ABCG1 gene expression in monocytes is partially mediated by DNA methylation [31]. Previous studies have demonstrated that methylation of ABCG1 CpG sites cg06500161 and cg27243685 in the blood is positively associated with plasma triglyceride concentration and could be linked to obesity and metabolic syndrome [28, 33, 48,49,50,51,52]. One possible explanation is that ABCG1 could regulate the bioavailability and the subsequent activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), a rate-limiting enzyme that hydrolyzes circulating triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [53, 54]. Reduced LPL activity in SAT could result in increased the plasma triglyceride levels, thus explaining the positive correlation between ABCG1 methylation and triglyceride levels observed in this study [54]. A previous in vitro study has demonstrated a reduction in macrophage ABCG1 expression when higher triglyceride levels were present in the culture medium, indicating that hypertriglyceridemia can contribute to macrophage reverse cholesterol transport reduction in the vascular wall [49]. Existing data suggests that obesity-related hypertriglyceridemia is associated with CAD risk via ABCG1 gene expression dysregulation [42, 55].

Interestingly, ABCA1 mRNA levels in SAT were reduced in patients with a history of smoking (including smokers and ex-smokers) compared with patients who never smoked, indicating that mRNA levels did not increase after giving up smoking. These results are in accordance with a previous study, in which a similar relationship between smoking and ABCA1 expression in blood monocytes was observed [56]. However, DNA methylation levels in the ABCA1 and ABCG1 loci has not been associated with smoking status. No significant association was observed between ABCA1 DNA methylation levels in blood and tobacco smoking in another study [28].

Thus, ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA levels in adipose tissue from CAD patients are likely to be influenced by additional risk factors, such as smoking, age, diet and obesity [26], which can partially explain the lack of association between ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation levels and the corresponding mRNA levels in our study. Gene expression is influenced by many factors in addition to DNA methylation, and currently, there is no clear understanding of the levels of DNA methylation required for transcriptional inactivation of different genes: thus, DNA methylation levels only partially predict gene expression [57]. mRNA levels are affected by additional processes, including microRNA-mediated degradation [58, 59]. We did not assess microRNA levels in this study.

The present study demonstrated higher levels of ABCA1 DNA methylation in EAT compared with SAT in CAD patients. These observed differences in methylation levels in EAT and SAT partly could partly be linked to adipose tissue types. EAT is a type of visceral adipose tissue, whereas SAT represents fat depot of different origin [60]. Moreover, for ABCG1 we observed a slight increase in ABCG1 DNA methylation in EAT but also in SAT (significant for cg06500161). It may be hypothesized that changes in ABCG1 DNA methylation in adipose tissue may be related partly to obesity, as it discussed above. Additionally, this could be a result of statin treatment, as differences in DNA methylation were seen in both types of adipose tissues. Indeed, statin users have been shown to have higher methylation levels in ABCG1 CpG sites cg06500161 and cg27243685 in blood [61]. However, ABCA1 methylation is not known to be influenced by statins [61]. Thus, increased methylation levels of ABCA1 in EAT compared with SAT in CAD patients could be due to principal fat depot differences. This phenomenon could be linked to the pro-inflammatory profile of EAT, highlighting the importance of reverse cholesterol transport in EAT and supporting the hypothesis of epicardial fat tissue involvement in the pathogenesis of CAD.

There are several limitations to this study. One limitation is limited sample sizes of the studied groups, especially the NCAD group. Difficulties of material collecting are connected to variable interindividual amount of EAT which restricts dissecting the necessary size of EAT fragment in all cases, especially in the NCAD patients when EAT thickness is quite small. This additionally explains the fact that there are no differences in EAT thickness between the CAD and NCAD groups in this study. Another limitation is that patients from the CAD group, who were prescribed statins, were slightly overweight. Besides this, they were predominantly male and included a large proportion of smokers. Clinical heterogeneity and additional environmental factors might influence the expression profiles. The listed limitations partly explain that there was no association of mRNA levels with CAD and no correlation between DNA methylation and mRNA levels was found in this study. However we identified a subgroup of CAD patients with reduced ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT who underwent additional examination and had a proven concomitant carotid artery disease or a peripheral artery disease. Gender differences of obesity degree could be mentioned as a limitation. Although obesity was equally distributed in both studied groups waist circumference was higher in men with CAD. This could be addressed to a general feature of the population: women at the age usual for CAD manifestation are obese compared to men. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to analyze DNA methylation of the ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes in EAT. DNA methylation of these genes in blood leukocytes was not shown to be different between men and women in the other studies [24, 30]. Thus, we suppose gender differences of our studied groups are not linked to revealed changes in DNA methylation.

Conclusion

ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA hypermethylation in EAT is associated with CAD. Multifocal atherosclerosis is accompanied by decreased ABCA1 mRNA expression in EAT. ABCG1 methylation in SAT could be linked to hypertriglyceridemia and obesity. Taken together, our results support the involvement of ABCA1 and ABCG1 methylation in EAT in CAD development.

Availability of data and materials

DNA methylation data (pyrosequencing files) are available in GitHub repository https://github.com/lynxf/lab_ABCG1_ABCA1_methylation. Additional data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABCA1:

-

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1:

-

ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- EAT:

-

Epicardial adipose tissue

- HDL:

-

High density lipoproteins

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoproteins

- NCAD group:

-

Non-CAD group

- SAT:

-

Subcutaneous adipose tissue

References

Tchernof A, Despres JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):359–404.

Rabkin SW. Epicardial fat: properties, function and relationship to obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8:253–61.

Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(6):363–71.

Wu F, Chou K, Huang Y, Wu M. The relation of location-specific epicardial adipose tissue thickness and obstructive coronary artery disease: systemic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:62.

Gorter PM, van Lindert AS, de Vos AM, Meijs MFL, van der Graaf Y, Doevendans PA, et al. Quantification of epicardial and peri-coronary fat using cardiac computed tomography; reproducibility and relation with obesity and metabolic syndrome in patients suspected of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:896–903.

Kim MN, Park SM, Cho DH, Kim HL, Shin MS, Kim MA, et al. The relationship between epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery stenosis by sex and menopausal status in patients with suspected angina. Biol Sex Differ. 2018;9:52.

Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–6.

Sacks HD, Fain JN, Cheema P, Bahouth SW, Garrett E, Wolf RY, et al. Depot-specific overexpression of proinflammatory, redox, endothelial cell, and angiogenic genes in epicardial fat adjacent to severe stable coronary atherosclerosis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9(6):433–9.

Salgado-Somoza A, Teijeira-Fernández E, Luis Fernández A, González-Juanatey JR, Eiras S. Changes in lipid transport-involved proteins of epicardial adipose tissue associated with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224:492–9.

Yu BL, Zhao SP, Hu JR. Cholesterol imbalance in adipocytes: a possible mechanism of adipocytes dysfunction in obesity. Obes Rev. 2010;11:560–7.

Chung S, Parks JS. Dietary cholesterol effects on adipose tissue inflammation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27(1):19–25.

Duong M, Uno K, Nankivell V, Bursill C, Nicholls SJ. Induction of obesity impairs reverse cholesterol transport in ob/ob mice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0202102.

Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR. The role of HDL, ABCA1 and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:139–43.

Chung S, Sawyer JK, Gebre AK, Maeda N, Parks JS. Adipose tissue ATP binding cassette transporter A1 contributes to high-density lipoprotein biogenesis in vivo. Circulation. 2011;124:1663–72.

Cuffe H, Liu M, Key CC, Boudyguina E, Sawyer JK, Weckerle A, et al. Targeted deletion of adipocyte ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter A1) impairs diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(4):733–43.

Choromanska B, Mysliwiec P, Hady HR, Dadan J, Mysliwiec H, Bonda T, et al. The implication of adipocyte ATP-binding cassette A1 and G1 transporters in metabolic complications of obesity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;70(1):1–12.

Vincent V, Thakkar H, Aggarwal S, Mridha AS, Ramakrishnan L, Singh A. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) expression in adipose tissue and its modulation with insulin resistance in obesity diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity. Targets Therapy. 2019;12:275–84.

Frisdal E, Le Lay S, Hooton H, Poupel L, Olivier M, Alili R, et al. Adipocyte ATP-binding cassette G1 promotes triglyceride storage, fat mass growth, and human obesity. Diabetes. 2015;64(3):840–55.

Miroshnikova VV, Panteleeva AA, Bazhenova EA, Demina EP, Usenko TS, Nikolaev MA, et al. Regulation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 transporter gene expression in the intraabdominal adipose tissue. Biochem (Moscow) Suppl Ser B Biomed Chem. 2016;10:327–34.

Nazarenko MS, Markov AV, Lebedev IN, Freidin MB, Sleptcov AA, Koroleva IA, et al. A comparison of genome-wide DNA methylation patterns between different vascular tissues from patients with coronary heart disease. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122601.

Zaina S, Heyn H, Carmona FJ, Varol N, Sayols S, Condom E, et al. DNA methylation map of human atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7(5):692–700.

Aavik E, Lumvuori H, Leppanen O, Wirth T, Hakkinen SK, Brasen JH, et al. Global DNA methylation analysis of human atherosclerotic plaques reveals extensive genomic hypomethylation and reactivation at imprinted locus 14q32 involving induction of a miRNA cluster. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(16):993–1000.

Fujii R, Yamada H, Munetsuna E, Yamazaki M, Ando Y, Mizuno G, et al. Associations between dietary vitamin intake, ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation, and lipid profiles in a Japanese population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(5):1213–9.

Peng P, Wang L, Yang X, Huang X, Ba Y, Chen X, et al. A preliminary study of the relationship between promoter methylation of the ABCG1, GALNT2 and HMGCR genes and coronary heart disease. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e102265.

Ghaznavi H, Mahmoodi K, Soltanpou MS. A preliminary study of the association between the ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation and coronary artery disease risk. Mol Biol Res Commun. 2018;7(2):59–65.

Guay SP, Légaré C, Houde AA, Mathieu P, Bossé Y, Bouchard L. Acetylsalicylic acid, aging and coronary artery disease are associated with ABCA1 DNA methylation in men. Clin Epigenet. 2014;6(1):14.

Qin X, Li J, Wu T, Wu Y, Tang X, Gao P, Li L, et al. Overall and sex-specific associations between methylation of the ABCG1 and APOE genes and ischemic stroke or other atherosclerosis-related traits in a sibling study of Chinese population. Clin Epigenet. 2019;11(1):189.

Pfeiffer L, Wahl S, Pilling LC, Reischl E, Sandling JK, Kunze S, et al. DNA methylation of lipid-related genes affects blood lipid levels. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8(2):334–42.

Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(11):1427–31.

Guay SP, Brisson D, Munger J, Lamarche B, Gaudet D, Bouchard L. ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation is associated with HDL particle profile and coronary artery disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Epigenetics. 2012;7(5):464–72.

Dayeh T, Tuomi T, Almgren P, Perfilyev A, Jansson PA, de Mello VD, et al. DNA methylation of loci within ABCG1 and PHOSPHO1 in blood DNA is associated with future type 2 diabetes risk. Epigenetics. 2016;11(7):482–8.

Campanella G, Gunter MJ, Polidoro S, Krogh V, Palli D, Panico S, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of adiposity and future risk of obesity-related diseases. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(12):2022–35.

Yoon G, Zheng Y, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Gao T, Joyce B, et al. Ultra-high dimensional variable selection with application to normative aging study: DNA methylation and metabolic syndrome. BMC Bioinform. 2017;18(1):156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1568-1.

Ma Y, Follis JL, Smith CE, Tanaka T, Manichaikul AW, Chu AY, et al. Interaction of methylation-related genetic variants with circulating fatty acids on plasma lipids: a meta-analysis of 7 studies and methylation analysis of 3 studies in the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology consortium. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):567–78.

Ma SC, Zhang HP, Kong FQ, Zhang H, Yang C, He YY, Wang YH, et al. Integration of gene expression and DNA methylation profiles provides a molecular subtype for risk assessment in atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(6):4791–9.

Truong V, Huang S, Dennis J, Lemire M, Zwingerman N, Aïssi D, et al. Blood triglyceride levels are associated with DNA methylation at the serine metabolism gene PHGDH. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09552-z.

Dekkers KF, van Iterson M, Slieker RC, Moed MH, Bonder MJ, van Galen M, et al. Blood lipids influence DNA methylation in circulating cells. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1000-6.

Fernández-Sanlés A, Sayols-Baixeras S, Subirana I, Degano IR, Elosua R. Association between DNA methylation and coronary heart disease or other atherosclerotic events: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:325–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.05.022.

Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407(6801):233–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/35025203.

Lv YC, Tang YY, Zhang P, Wan W, Yao F, He PP, et al. Histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2-mediated ABCA1 promoter DNA methylation contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6): e0157265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157265.

Hedman ÅK, Mendelson MM, Marioni RE, Gustafsson S, Joehanes R, Irvin MR, et al. Epigenetic patterns in blood associated with lipid traits predict incident coronary heart disease events and are enriched for results from genome-wide association studies. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(1): e001487. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001487.

Mauldin JP, Nagelin MH, Wojcik AJ, Srinivasan S, Skaflen MD, Ayers CR, et al. Reduced expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 increases cholesterol accumulation in macrophages of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;117:2785–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741314.

Miroshnikova VV, Demina EP, Majorov NV, Davydenko VV, Kurjanov PS, Vavilov VN, et al. ABCG1 transporter gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with atherosclerosis. Tsitologiia. 2014;56(3):234–40 (Article in Russian).

Demina EP, Miroshnikova VV, Maĭorov NV, Davydenko VV, Shvartsman AL. ABCA1 mRNA and protein levels in M-CSF-activated macrophages from patients with arterial stenosis. Tsitologiia. 2013;55(8):580–5 (Article in Russian).

Infante T, Forte E, Schiano C, Punzo B, Cademartiri F, Cavaliere C, et al. Evidence of association of circulating epigenetic-sensitive biomarkers with suspected coronary heart disease evaluated by Cardiac Computed Tomography. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1): e0210909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210909.

Chau YY, Bandiera R, Serrels A, Martínez-Estrada OM, Qing W, Lee M, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous fat have different origins and evidence supports a mesothelial source. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(4):367–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2922.

Demerath EW, Guan W, Grove ML, Aslibekyan S, Mendelson M, Zhou YH, et al. Epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of BMI, BMI change and waist circumference in African American adults identifies multiple replicated loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(15):4464–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv161.

Sayols-Baixeras S, Subirana I, Lluis-Ganella C, Civeira F, Roquer J, Do AN, et al. Identification and validation of seven new loci showing differential DNA methylation related to serum lipid profile: an epigenome-wide approach. The REGICOR study. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(20):4556–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddw285.

Wong BX, Kyle RA, Croft KD, Quinn CM, Jessup W, Yeap BB. Modulation of macrophage fatty acid content and composition by exposure to dyslipidemic serum in vitro. Lipids. 2011;46:371–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-011-3528-2.

Tavoosi Z, Moradi-Sardareh H, Saidijam M, Yadegarazari R, Borzuei S, Soltanian A, Goodarzi MT. Cholesterol transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cholesterol. 2015;2015:682904.

Akinyemiju T, Do AN, Patki A, Aslibekyan S, Zhi D, Hidalgo B, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of metabolic syndrome in African-American adults. Clin Epigenet. 2018;10:49.

Koh IU, Choi NH, Lee K, Yu HY, Yun JH, Kong JH, et al. Obesity susceptible novel DNA methylation marker on regulatory region of inflammation gene: results from the Korea Epigenome Study (KES). BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1): e001338. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001338.

Olivier M, Tanck MW, Out R, Villard EF, Lammers B, Bouchareychas L, et al. Human ATP-Binding Cassette G1 controls macrophage lipoprotein lipase bioavailability and promotes foam cell formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(9):2223–31. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.111.243519.

Kobayashi J, Mabuchi H. Lipoprotein lipase and atherosclerosis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015;52(6):632–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563215590451.

Ding J, Reynolds LM, Zeller T, Müller C, Lohman K, Nicklas BJ, et al. Alterations of a cellular cholesterol metabolism network are a molecular feature of obesity-related type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2015;64(10):3464–74. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-1314.

Song W, Wang W, Dou LY, Wang Y, Xu Y, Chen LF, Yan XW. The implication of cigarette smoking and cessation on macrophage cholesterol efflux in coronary artery disease patients. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(3):682–91.

Zhong H, Kim S, Zhi D, Cui X. Predicting gene expression using DNA methylation in three human populations. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6757. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6757.

Price NL, Rotllan N, Zhang X, Canfrán-Duque A, Nottoli T, Suarez Y, Fernández-Hernando C. Specific disruption of Abca1 targeting largely mimics the effects of miR-33 knockout on macrophage cholesterol efflux and atherosclerotic plaque development. Circ Res. 2019;124(6):874–80. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314415.

Yang S, Ye ZM, Chen S, Luo XY, Chen SL, Mao L, et al. MicroRNA-23a-5p promotes atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability by repressing ATP-binding cassette transporter A1/G1 in macrophages. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;123:139–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.09.004.

Ma X, Kang S. Functional implications of DNA methylation in adipose biology. Diabetes. 2019;68(5):871–8.

Ochoa-Rosales C, Portilla-Fernandez E, Nano J, Wilson R, Lehne B, Mishra PP, et al. Epigenetic link between statin therapy and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:875–84. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-1828.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was partly supported by Russian foundation for basic research [RFBR; project mol a 18-315-00382 – gene expression experiments and sample preparations for pyrosequencing]; the funding body had no influence on design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: SNP, VPP, MSN, EIB. Sample acquisition and collection of clinical data: EAP, OAB, ODB. Experiments: VVM, AAP, IAP, NDR, AVM. Data analysis: VVM, AAP. Manuscript writing: VVM, SNP. Editing and Reviewing: MSN, AVM. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Committee on Ethics of Pavlov First Saint-Petersburg State Medical University (Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation). This study also complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representatives before the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primers and probes for TaqMan RT-PCR.

Additional file 2: Fig. S1.

Proportional diagram of the structure of ABCA1 (NM_005502.4) (A) and ABCG1 (NM_207174.1) (A) genes and loci selected for DNA methylation analysis. The line represents the gene (left to right: 5′–3′). Solid rectangles represent exons. Because of the long length of ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes, exons distant from the analyzed regions are omitted. ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette A1 gene; ABCG1, ATP-binding cassette G1 gene.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

ABCA1 promoter DNA methylation levels (%) in EAT and SAT in studied groups.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

ABCG1 DNA methylation levels (%) in EAT and SAT in studied groups.

Additional file 5.

The origin bands of WB.The origin bands of WB.

Additional file 6: Fig. S2.

ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT and SAT in subgroups divided according to smoking status. A ABCA1 mRNA levels in EAT; B ABCA1 mRNA levels in SAT (p = 0.030); C ABCG1 mRNA levels in EAT; D ABCG1 mRNA levels in SAT.

Additional file 7: Fig. S3.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r) between CpG site methylation levels within analyzed loci: A for ABCA1 in SAT; B for ABCA1 in EAT; C for ABCG1 in SAT; D for ABCG1 in EAT. Filled squares in the case of ABCG1 gene represent correlations in the same locus, unpainted—between two different loci. *p < 0,01; **p < 0,05; for rest cells p = 0.000.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Miroshnikova, V.V., Panteleeva, A.A., Pobozheva, I.A. et al. ABCA1 and ABCG1 DNA methylation in epicardial adipose tissue of patients with coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 566 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02379-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02379-7