Abstract

Background

Heilongjiang Province has a long and cold winter season (the minimum temperature can reach -30 ℃), and few winter wheat varieties can safely overwinter. Dongnongdongmai1 (Dn1) is the first winter wheat variety that can safely overwinter in Heilongjiang Province. This variety fills the gap for winter wheat cultivation in the frigid region of China and greatly increases the land utilization rate. To understand the molecular mechanism of the cold response, we conducted RNA-sequencing analysis of Dn1 under cold stress.

Results

Approximately 120,000 genes were detected in Dn1 under cold stress. The numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the six comparison groups (0 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -5 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -10 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -15 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -20 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ and -25 ℃ vs. 5 ℃) were 11,313, 8313, 15,636, 13,671, 14,294 and 13,979, respectively. Gene Ontology functional annotation suggested that the DEGs under cold stress mainly had “binding”, “protein kinase” and “catalytic” activities and were involved in “oxidation–reduction”, “protein phosphorylation” and “carbohydrate metabolic” processes. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment analysis indicated that the DEGs performed important functions in cold signal transduction and carbohydrate metabolism. In addition, major transcription factors (AP2/ERF, bZIP, NAC, WRKY, bHLH and MYB) participating in the Dn1 cold stress response were activated by low temperature.

Conclusion

This is the first study to explore the Dn1 transcriptome under cold stress. Our study comprehensively analysed the key genes involved in cold signal transduction and carbohydrate metabolism in Dn1 under cold stress. The results obtained by transcriptome analysis could help to further explore the cold resistance mechanism of Dn1 and provide basis for breeding of cold-resistant crops.

Highlights

• Approximately 120,000 genes were detected in Dn1 during the overwintering stage (the lowest sampling temperature was -25 °C), of which 31,000 genes were differentially expressed.

• A total of 1230 differentially expressed genes involved in cold signal perception and transduction were detected in Dn1 during the overwintering stage.

• A total of 1715 differentially expressed genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism were detected in Dn1 during the overwintering stage, most of which were enriched in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and starch and sucrose metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cold stress, a major type of abiotic stress, is able to restrict the growth, development, yield and geographic distribution of many important crops [1]. Cold stress is divided into chilling stress (0–15 ℃) and freezing stress (< 0 ℃), which can cause different degrees of damage to plants [2]. Chilling stress can lead to hardening of the cell membrane, instability of protein complexes, and disruption of photosynthesis. Freezing stress promotes the formation of ice in the intercellular space, and the accumulated intercellular ice disrupts the cell membrane [3]. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important food crops in China [4]. In winter, it is extremely cold in northeast China, especially Heilongjiang Province where the minimum temperature can reach -30 ℃. The low temperature and insufficient effective accumulated temperature cause the cultivated wheat to ripen once a year, with a low land utilization rate, which is the main reason for the lower wheat cultivation area in Heilongjiang Province. Therefore, exploring the cold resistance mechanism of wheat and enhancing the cold resistance of wheat are of great significance to agricultural development in alpine regions.

Plants have evolved complex physiological and molecular mechanisms to withstand cold stress. One of the best characterized mechanisms is cold acclimation [5]. During this process, a series of physiological and biochemical changes occur. Plants synthesize proline, soluble sugar and protective proteins (late embryogensis abundant proteins, antifreeze proteins and cold shock proteins) to increase their cold stress tolerance [6]. Among the numerous and complex cold acclimation signalling pathways, the best understood ICE-CBF-COR pathway, initiated by the calcium signalling cascade, plays a central role [7]. In recent years, researchers have also found that CBF-dependent pathways are modulated by important regulators at the transcriptional, posttranscriptional and posttranslational levels [8]. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful technology capable of revealing the global transcriptional activities of any species at the mononucleotide level [9, 10].

In previous studies, researchers have comprehensively analysed gene functions and metabolic pathways at the transcriptional level under cold stress using RNA-seq technology [9, 11, 12]. Recent plant transcriptome studies have found that calcium ion (Ca2+) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated signalling pathways and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades in plants are able to rapidly respond to cold stress [13, 14]. The cold response of plants is a complex process that involves the regulation of a set of transcription factors (TFs) and various genes. Jiang et al. [15] revealed the complex mechanism of TFs in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in response to cold stress and the importance of hormone signal transduction and plant-pathogen interactions in plant cold tolerance using RNA-seq. Zhou et al. [11] found that the expression of some members of the AP2/ERF, WRKY, NAC, and bZIP families of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) was significantly up/downregulated under freezing stress and that galactose metabolism was involved in plant freezing tolerance using RNA-seq. Dong et al. [9] found significant changes in related gene expression in glycolysis and the TCA cycle in the Poa pratensis L. transcriptome, which are involved in improving cold tolerance in plants.

In recent years, there have been several reports on the transcriptome of wheat under drought [16, 17], cold [18,19,20], heat [21] and water [22] stress. All three studies of the wheat transcriptome under cold stress were conducted on seedling-stage wheat cultivated in a greenhouse. Díaz [19] and Aleliūnas [20] sampled winter wheat leaves under chilling stress at 2 ℃ and 5 ℃ for transcriptome sequencing, respectively, and found that hormone signalling pathways, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, and amino acid accumulation were involved in plant cold tolerance. Zhao et al. [18] comprehensively analysed the transcriptome and metabolome of winter wheat crowns under chilling and freezing stress and found that abscisic acid/jasmonic acid signalling and proline biosynthesis played important roles in regulating wheat cold tolerance. However, transcriptome study of tillering nodes of winter wheat in the field under cold stress is still scarce.

Winter wheat is sown and cultivated in autumn and harvested in the following summer, and one aim is to utilize winter moisture to increase yield [23]. Dongnongdongmai1 (Dn1) is the first wheat variety that is capable of safe overwintering in the frigid region of Heilongjiang Province, and the regreening rate after winter is greater than 85%. Our previous studies found that Dn1 transcription factor (TabZIP1) [24] and key carbohydrate metabolism enzymes (TaG6PDH, Ta6PGDH and TaFBA-A10) [25, 26] are involved in improving plant cold tolerance. We also demonstrated the important role of tillering nodes in the wintering stage of winter wheat [25, 26]. The adaptation of plants to low temperature is a complex process that requires the joint regulation of multiple biological processes. To respond to these biological processes, plants need to alter the expression of a large number of genes. Therefore, it is difficult to reveal the complex mechanism underlying the cold response by studying a single gene and a single metabolic pathway. In this study, we comprehensively analysed the transcriptome of winter wheat Dn1 in the field under cold stress, aiming to discover important cold resistance genes and explore the complex cold resistance mechanisms activated during the wintering period.

Results

Changes in Dn1 phenotype at low temperatures

Our results showed the changes in Dn1 phenotype under cold stress. Under chilling temperatures (5 ℃ and 0 ℃), Dn1 leaves grew normally. When the temperature dropped below 0 ℃, the leaves lost water and wilted. However, tillering nodes consistently maintained good growth under cold stress (Fig. 1).

Quality analysis and sequence assembly of RNA-seq data

The winter wheat tillering nodes were collected at 5 ℃, 0 ℃, -5 ℃, -10 ℃, -15 ℃, -20 ℃ and -25 ℃ (average minimum temperature for ten consecutive days). Total RNA extracted from tillering nodes by using the Illumina Hiseq 4000 sequencing system was used to construct an expression library for sequencing. We obtained 21 library reads (three biological replicates for each temperature sample), and each library had approximately 49 million reads. There were approximately 45 million clean reads per library after filtering, which represented on average 91.23% of the total reads of all libraries. In all samples, the Q30 value was over 98%, and the guanine and cytosine (GC) content was 49%. There are approximately 42 million reads per library that could be aligned to the genome, of which there are approximately 31 million reads that could only be uniquely aligned to one location on the genome and 11 million reads that could be aligned to multiple locations on the genome (Table 1). A total of approximately 120,000 genes were detected in each library (Table S1). This suggests that the RNA-seq data are robust quality and reliable results are obtained from the transcriptome assembly.

DEGs obtained under cold stress

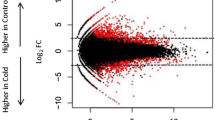

To understand how the gene expression patterns changed in Dn1 under cold stress, we performed an analysis of FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments) values across the transcriptome. The specific DEGs at different temperatures were analysed with 5 °C as the control (Table S2). In the 0 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group, there were 11,313 DEGs (6049 upregulated genes and 5264 downregulated genes). In the -5 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group, there were 8313 DEGs (4645 upregulated genes and 3668 downregulated genes). In the -10 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group, there were 15,636 DEGs (7251 upregulated and 8385 downregulated genes). In the -15 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group, there were 13,671 DEGs (6989 upregulated and 6682 downregulated genes). In the -20 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group, there were 14,294 DEGs (7561 upregulated and 6733 downregulated genes). In the -25 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ com parison group, there were 14,294 DEGs (7193 upregulated and 6786 downregulated genes). This suggests that these genes are involved in cold resistance (Fig. 2).

Numbers of DEGs in the tillering node of Dn1 under cold stress. The 5 ℃ condition was included as the control. Tn_5 indicates 5 ℃ samples, Tn_0 indicates 0 ℃ samples, Tn_M5 indicates -5 ℃ samples, Tn_M10 indicates -10 ℃ samples, Tn_M15 indicates -15 ℃ samples, Tn_M20 indicates -20 ℃ samples, Tn_M25 indicates -25 ℃ samples

In Fig. 3, 2550 common genes were detected in Dn1 among the six different comparison groups, suggesting that these genes were involved in the process of responding to cold stress at different low temperatures. In addition, a large number of DEGs were generated at extremely low temperatures of -10 ℃, -15 ℃, -20 ℃ and -25 ℃, especially at -10 ℃, compared with other temperatures. A higher number of unique DEGs were generated at 0 ℃, -10 ℃, and -20 ℃.

In this study, we randomly selected six DEGs for qRT-PCR validation. The sequences of all the primers needed for the experiments are shown in Table S3. The results showed high congruence (R2 = 0.96) between qRT-PCR data and RNA-seq data (Fig. 4 and Fig. S1). This suggests that the RNA-seq data are highly credible for use in further analysis.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs

Dn1 produced a large number of DEGs under cold stress. To explore the potential function of DEGs, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. The results showed that 31,003 DEGs were classified into 3101 GO terms, including three categories: “biological process”, “cellular component” and “molecular function”. The main biological processes were “oxidation–reduction process”, “protein phosphorylation” and “carbohydrate metabolic process”. The main cellular components were “nucleus”, “membrane”, “chloroplast” and “cytoplasm”. The main molecular functions were “binding”, “protein kinase activity” and “catalytic activity” (Fig. 5).

To explore the metabolic pathways involved in cold stress in depth, we performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. The 20 common metabolic pathways with the greatest enrichment were exhibited in the comparison of seven temperatures (Fig.6). Among these top pathways, there were many significantly up/downregulated genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pentose phosphate pathway and fructose and mannose metabolism. In addition, the MAPK signalling pathway was highly enriched in each of the six comparison groups (0 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -5 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -10 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -15 ℃ vs. 5 ℃, -20 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ and -25 ℃ vs. 5 ℃). Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis was highly enriched at low temperatures, except at -5 and -10 ℃. However, starch and sucrose metabolism was only highly enriched at 0 and -5 ℃. The pentose phosphate pathway and ABC transporters were highly enriched at 0 and -5 ℃, and fructose and mannose metabolism were highly enriched at -10, -15, -20 and -25 ℃. Furthermore, we also found that plant hormone signal transduction was enriched only in the -5 ℃ vs. 5 ℃ comparison group. Briefly, a large number of genes in different pathways are involved in Dn1 cold resistance. It is possible to deeply explore the Dn1 cold resistance mechanism from different perspectives (Fig. S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7).

KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the seven temperature comparison groups. The Y axis corresponds to the KEGG pathway, and the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The colour of the dot represents the p value, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the reference pathway

DEGs involved in cold signal transduction

A rapid increase in Ca2+ concentrations in the cytoplasm is considered the earliest cold signalling event. The opening of channels is responsible for the rapid increase in Ca2+ concentrations. In Dn1, the expression of genes encoding three calcium channels, including mid1 complex activity (MCAs), calcium sensor synaptotagmin (SYTs) and cyclic nucleotide gated channels (CNGCs), was upregulated under cold stress. The calcium signal is transmitted through Ca2+ sensors. In Dn1, we also found that the expression of genes encoding calcium sensors, including calmodulins (CaMs), CaM-like (CMLs), Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CPKs/CDPKs) and calcineurin B-like (CBLs), was upregulated under cold stress. In addition, the expression of genes encoding CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) and Ca2+/CaM-regulated receptor-like kinases (CRLKs) was also upregulated under cold stress. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling cascade positively responds to cold stress. The expression of genes encoding three kinases, including MAP kinase kinase kinases (MEKKs), MAP kinase kinases (MEKs) and MAP kinases (MPKs), was upregulated in Dn1 under cold stress. Respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) are involved in the increase in ROS induction by calcium ions under cold stress. The expression of RBOHs was upregulated in Dn1 under cold stress (Fig. 7).

Expression pattern analysis of cold signal transduction-related genes. A Expression pattern of genes encoding Ca2+ channel proteins. B Expression pattern of genes encoding Ca 2 + si gnal transduction-related proteins. C Expression pattern of genes encoding MAPK signal cascade-related proteins. D Expression pattern of genes encoding RBOH

Key transcription factors associated with cold stress

Transcription factors are involved in the regulation of the plant cold response. In this study, we analysed the expression of the AP2/ERF, bZIP, NAC, WRKY, bHLH and MYB transcription factors under cold stress. In all libraries, we found a total of 1021 transcription factors differentially expressed under cold stress (Table S4), which included 85 bZIP members (Fig. S8), 93 NAC members (Fig. S9), 105 WRKY members (Fig. S10), 189 bHLH members (Fig. S11), 215 AP2/ERF members (Fig. S12) and 334 MYB members (Fig. S13). A heatmap was generated to show the FPKM values of differentially expressed transcription factors. Transcription factors with potential research value were selected for illustration. Among the AP2/ERF members, the expression of TaCBF1 (TraesCS5D02G318300), TaCBF2 (TraesCS5B02G312000), TaAP2-D (TraesCS2D02G515800), TaDREB-W73 (TraesCS3A02G099200), TaCBFIVd (TraesCS5A02G310500) and TaERF5a (TraesCS5B02G214400) was upregulated at freezing temperatures. The expression of TaERF4 (TraesCS2D02G543900) and TaRDFL1a (TraesCS5D02G200900) was downregulated with decreasing temperature. Among the bHLH members, the expression of TabHLH3 (TraesCS3A02G028200), TabHLH59 (TraesCS5B02G445900), TabHLH89 (TraesCS5D02G286300) and TabHLH137 (TraesCS5A02G292900) was upregulated at freezing temperatures. TabHLH168 (TraesCS5A02G533300) expression peaked at -15 ℃. The expression of TabHLH27 (TraesCS2B02G289900) was downregulated with decreasing temperature and barely expressed at temperatures lower than -10 ℃. Among the bZIP members, the expression of TabZIP25 (TraesCS5A02G057500, TraesCS5B02G059200 and TraesCS5D02G068800) and TabZIP53 (TraesCS1B02G091500 and TraesCS1D02G075500) was upregulated at freezing temperatures. However, TabZIP12 (TraesCS3B02G411300) and TabZIP44 (TraesCS5D02G183500) only had increased expression at chilling temperature (0 ℃). Among the MYB members, the expression of TaMYB4 was upregulated at freezing temperatures. The expression of TaMYB13 (TraesCS3A02G535100, TraesCS3B02G612200 and TraesCS3D02G540600) and TaMYB59 (TraesCS1B02G055200) was upregulated at low temperatures, especially at 0 ℃ and -20 ℃. TaMYB75 (TraesCS1A02G083100, TraesCS1B02G100600 and TraesCS1D02G084400) had higher expression at -5 ℃, -15 ℃ and -25 ℃. The expression of TaMYB15 (TraesCS2D02G378400) and TaMYB33 (TraesCS6A02G224000) was downregulated with decreasing temperature. Among the NAC members, the expression of TaNAC2 (TraesCS5A02G468300 and TraesCS5D02G481200) and TaNAC71 (TraesCS4A02G219700, TraesCS4B02G098200 and TraesCS4D02G094400) was upregulated at freezing temperatures. TaNAC79 (TraesCS1A02G266300, TraesCS1B02G277300 and TraesCS1D02G266500) expression peaked at 0 °C, and TaNAC18 (TraesCS7A02G263100) expression peaked at -5 °C. Among the WRKY members, the expression of TaWRKY1 (TraesCS5A02G059100 and TraesCS5B02G066400), TaWRKY4 (TraesCS5B02G108500 and TraesCS5D02G116100) and TaWRKY19 (TraesCS2B02G209200 and TraesCS2D02G190500) was upregulated at freezing temperatures. TaWRKY40 (TraesCS4A02G128100, TraesCS4B02G176700 and TraesCS4D02G178400) had higher expression at 0 °C and -10 °C. The expression of TaWRKY74 (TraesCS5D02G190800) was downregulated with decreasing temperature (Fig. 8).

DEGs involved in carbohydrate metabolism

Changes in carbohydrate homeostasis are extremely important for cold resistance when plants are exposed to low temperatures. Through KEGG enrichment analysis, we found a large number of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism in Dn1 under cold stress, which included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, starch and sucrose metabolism and fructose and mannose metabolism. A total of 163 DEGs encoding enzymes related to glycolysis/gluconeogenesis changed significantly under cold stress (Table S5). However, only a few genes encoding related enzymes had higher expression levels under cold stress (Fig. 9). These were hexokinases (EC 2.7.1.1), 6-phosphofructokinases (EC 2.7.1.11), fructose-bisphosphate aldolases (EC 4.1.2.13), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases (EC 1.2.1.12), phosphoglycerate kinases (EC 2.7.2.3), pyruvate kinases (EC 2.7.1.40), lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27), alcohol dehydrogenases (EC 1.1.1.1), aldehyde dehydrogenases (EC 1.2.1.3) and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatases (EC 3.1.3.11). Analysis of metabolic pathways revealed that hexokinases, fructose bisphosphate aldolases, and 6-phosphofructokinases were involved in not only glycolysis/gluconeogenesis but also fructose and mannose metabolism. In addition, the gene (TraesCS2B02G599300) encoding phosphomannomutase, which is involved in fructose and mannose metabolism, also had enhanced expression under cold stress. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase acts as the rate-limiting enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway, and the gene (TraesCS2A02G320400) encoding this enzyme showed enhanced expression under cold stress.

The expression of a total of 62 DEGs encoding enzymes related to starch and sucrose metabolism changed significantly under cold stress (Table S6). In addition to the DEGs encoding hexokinases, only a few genes encoding related metabolic enzymes had higher expression levels under cold stress (Fig. 10). These were sucrose-phosphate synthase (EC 2.4.1.14), sucrose phosphate phosphohydrolase (EC 3.1.3.24), sucrose synthase (EC 2.4.1.13), starch synthases (EC 2.4.1.21), alpha-amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) and beta-amylases (EC 3.2.1.2).

Discussion

Plants are sessile in nature, so the only way plants can survive in adverse environments is rapid and efficient adaptation to alterations in their surroundings [27]. Cold stress can affect plant growth and development and reduce crop yields [28]. Plant adaptation to cold stress is a complex process that undergoes a series of changes at both the physiological and molecular levels [6]. Dn1 is a strong cold-resistant winter wheat cultivar able to resist -30 ℃ temperatures in Heilongjiang Province. Understanding how Dn1 responds to cold stress will provide valuable information and genetic resources for improving cold stress tolerance in crops. Combined with the phenotype of Dn1 in this study (Fig. 1) and the physiological data determined in our previous study [29], we found that tillering nodes play an important role in the wintering stage of Dn1. In this study, we performed transcriptome sequencing of tillering nodes of Dn1 grown in a field using RNA-seq. The aim was to explore the cold signal perception, cold signal transduction and metabolic process of Dn1 in response to cold stress at the transcriptional level.

Signal transduction related genes involved in the Dn1 response to cold stress

Ca2+ is an important second messenger in plants in response to cold stress [30]. The cold stress-triggered Ca2+ signal is transmitted mainly by Ca2+ sensors, including CaMs, CMLs, CPKs/CDPKs and CBLs [31,32,33]. It has been reported that the expression of CaMs, CMLs, CDPKs and CBLs is upregulated in rice and maize transcriptome under cold stress [34, 35]. In this study, the expression of these Ca2+ binding protein genes was also differentially expressed in the Dn1 transcriptome under cold stress. Studies have revealed that OsCPK27, OsCPK25 and OsCPK17 are able to induce ROS, nitric oxide and MAPK pathways in response to cold stress [36,37,38,39]. In this study, the expression of CPKs was mainly significantly upregulated at 0 °C, indicating that these genes may function at chilling temperature. Only one CPK gene (TaesCS4B02G109800) was significantly upregulated at freezing temperatures, suggesting that this gene may play a unique role under cold stress. CBLs are able to decode Ca2+ signals through interaction with CIPKs, transmitting the signal to downstream phosphorylation events [40, 41]. Sun et al. [40] analysed the physical interaction between TaCBL and TaCIPK proteins in wheat and found that TaCBL2 interacted with TaCIPK11 and TaCIPK14 and that TaCBL6 interacted with TaCIPK11. In this study, we found that the expression of TaCBL2 (TraesCS5A02G060600 and TraesCS5D02G072100), TaCBL6 (TraesCS5A02G124700 and TraesCS5B02G124300), TaCIPK11 (TraesCS3A02G346100, TraesCS3B02G377800 and TraesCS3D02G339800) and TaCIPK14 (TraesCS4A02G194800, TraesCS4B02G120400 and TraesCS4D02G118500) was upregulated under cold stress. Therefore, we speculate that three CBL-CIPK interactions (TaCBL2-CIPK11, TaCBL2-CIPK14 and TaCBL6-CIPK11) occur under cold stress to transmit Ca2+ signals to downstream phosphorylation events. It has been reported that Ca2+ regulates CRLK1, a plasma membrane-associated serine/threonine kinase, which plays an important role in the plant response to cold stress [42]. Recent studies have shown that CRLK1 and CRLK2 may regulate the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 cascade to negatively regulate MPK3/6 in Arabidopsis thaliana L. under cold stress [43, 44]. In this study, the expression of TaCRLK2 (TraesCS4B02G315400), the gene with the highest homology to AtCRLK2, was upregulated and the expression of TaMPK3/6 (TraesCS4A02G106400, TraesCS4B02G197800 and TraesCS4D02G198600) was downregulated under cold stress. However, the expression of TaMEKK1 (TraesCS5A02G200800 and TraesCS5B02G199400), TaMKK2 (TraesCS7D02G092900) and TaMPK4 (TraesCS1A02G184500, TraesCS1B02G192600 and TraesCS7D02G295900) was downregulated or not significantly different under cold stress. These finding suggests that there are differences in regulation mechanisms between wheat and Arabidopsis, and TaCRLK2 may not negatively regulate TaMPK3/6 through the TaMEKK1-TaMKK2-TaMPK4 cascade. In addition, we found that the expression of TaMEK7 (TraesCS2A02G498000), TaMKK3 (TraesCS5D02G130900 and TraesCS5D02G549600), and TaMPK16/19/20 (TraesCS1B02G104900, TraesCS1D02G088000, TraesCS3A02G242100, TraesCS7B02G246900, TraesCS3A02G228000, TraesCS3D02G225600 and TraesCS7D02G342800) was upregulated under cold stress (Fig. 7B and C). Among them, the expression of MKK3 was also upregulated in maize (Zea mays L.) and cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) transcriptomes [45, 46]. This finding suggests that there may be other MAPK signalling cascade that regulates downstream cold-responsive gene expression in Dn1 under cold stress, which needs further exploration. RBOH encodes plasma membrane NADPH oxidase involved in Ca2+ induced ROS accumulation under cold stress [47]. In this study, we found that the expression of RBOHs (TraesCS3A02G354200 and TraesCS3B02G212900) was upregulated under cold stress, suggesting that an interaction mechanism between Ca2+ and ROS signalling may also exist in wheat (Fig. 7D). In summary, the increased expression of Ca2+ signalling protein transcripts in Dn1 activated a complex signalling cascade that regulated various downstream cold responsive genes.

Transcription factors involved in the Dn1 response to cold stress

It is well known that functional genes and regulatory genes work synergistically to improve cold tolerance in plants. Among the numerous regulatory genes, TFs play important roles in plants cold response [48]. Over the past two decades, the ICE-CBF-COR signalling pathway has been the best characterized cold stress signalling pathway [8]. Three cold-induced CBF genes (CBF1/DREB1B, CBF2/DREB1C and CBF3/DREB1A) in Arabidopsis are able to activate the expression of CORs to improve plant cold tolerance [49]. Heterologous expression of CBF1-3 from other species enhances cold tolerance in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) [50, 51]. In this study, TaCBF1 and TaCBF2 had higher expression levels at freezing temperatures (-15 ℃ to -25 ℃). This result indicates that TaCBF1 and TaCBF2 not only play a role in cold acclimation, but also improve the freezing tolerance of Dn1. Studies have shown that CBF genes belonging to CBFIIId, CBFIVa, CBFIVb, CBFIVc and CBFIVd groups display higher constitutive and cold-induced expression in winter cultivars of Pooideae compared to spring cultivars [52, 53]. In this study, TaCBFIIId-A15, TaCBFIIId-D19, TaCBFIVa-A2, TaCBFIVb-D20, TaCBFIVb-D21, TaCBFIVd-A22, TaCBFIVd-D9 and TaCBFIVd-D22 were differentially expressed in Dn1 under cold stress (Table S1). The higher constitutive and inducible expression within these CBF groups may play a predominant role in the superior cold tolerance capacity of Dn1.

ICE (INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION) is a MYC-type bHLH transcription factor. Both ICE1 and ICE2 positively regulate CBF expression and freezing tolerance [51, 54]. Studies have shown that ICE1 is differentially expressed in the transcriptome of cold-tolerant peanut and plays an important role under cold stress [15]. However, in this study, neither TaICE1 nor TaICE2 expression changed significantly under cold stress. We hypothesized that TaICE1 and TaICE2 are able to regulate the expression of TaCBFs in Dn1 under cold stress. This finding suggests that the protein activity of TaICE1 and TaICE2 is not entirely determined by the transcriptional level. Studies have shown that ICE1 protein activity is regulated by post-translational modifications in Arabidopsis under cold stress. HOS1 and MPK3/6 reduce ICE1 protein activity while SIZ1 and OST1 increase ICE1 protein activity [44, 55,56,57]. Interestingly, in this study, the expression of TaHOS1 (TraesCS4A02G247200, TraesCS4B02G067700 and TraesCS4D02G066700) did not significantly change and the expression of TaMPK3/6 was significantly downregulated, while the expression of TaSIZ1 (TraesCS1A02G065700, TraesCS1B02G083900 and TraesCS3A02G538000) was significantly upregulated under cold stress. This finding suggests that TaSIZ1 may mediate sumoylation of ICE1/2 to increase its protein activity and subsequently positively regulate TaCBFs expression in response to cold stress. Furthermore, the fold change in TabHLH3 expression is the largest in the bHLH transcription factor family of Dn1 under cold stress. Therefore, its regulatory mechanism under cold stress warrants further exploration.

MYB15, a member of the R2R3 subfamily of MYB domain proteins, negatively regulates cold-induced CBFs [58]. The expression of TaMYB15, in contrast to TaCBF1 and TaCBF2, showed a decreasing trend in Dn1 under cold stress. This suggests that the transcription of TaMYB15 may be suppressed under cold stress, thereby affecting TaMYB15 activity and attenuating the inhibition of downstream TaCBFs expression. In contrast to TaMYB15, the expression of TaMYB4 significantly increased under cold stress. Previous studies have shown that overexpression of OsMYB4 in Arabidopsis enhances cold tolerance of plants [59, 60]. It has also been reported that the bHLH3 and MYB4 interaction ensures the stable accumulation of flavonoids in mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruits [61]. Therefore, we speculate that TabHLH3 and TaMYB4 may interact to regulate cold tolerance in Dn1. However, the specific mechanism needs further exploration.

Carbohydrate metabolism in Dn1 under cold stress

Changes in carbohydrate content are directly related to the physiological activities of plants, such as photosynthesis, respiration and metabolic processes [62]. Studies have shown that many DEGs in the loquat transcriptome under cold stress are enriched in the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, pentose and glucose interconversion and fructose and mannose metabolism pathways [63]. This finding is consistent with our results. In this study, carbohydrate metabolism related DEGs were mainly mapped to glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and starch and sucrose metabolism. Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis is an important pathway that fuels respiration, and glucose and fructose further metabolism through this process provides energy (ATP) and reducing power (NADH) to plant cells [64]. Studies have shown that glycolysis is more sensitive to cold stress in cotton, Cucumis melo L. and Eucalyptus nitens (H. Deane & Maiden) Maiden, and the expression of genes encoding the three rate limiting enzymes (hexokinase, 6-phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase) of the glycolysis pathway was significantly upregulated under cold stress [65,66,67]. Our study showed that the expression of genes encoding hexokinase (TraesCS1A02G355200 and TraesCS1D02G355200), 6-phosphofructokinase (TraesCS1A02G344000 and TraesCS1D02G346200) and pyruvate kinase (TraesCS2A02G240200, TraesCS2D02G237900, TraesCS5B02G131000 and TraesCS5D02G138800) was also significantly upregulated under cold stress (Fig. 9). This finding suggests that these genes may play important roles in the glycolysis of Dn1 under cold stress and promote the metabolism of glucose and fructose to provide ATP and NADH to plants.

The accumulation of sucrose and soluble sugar in plants under cold stress plays an important role in osmoprotection, maintenance of membrane stability, protein stability, carbohydrate homeostasis and intracellular expansion [68,69,70]. Jiang et al. [71] found that the expression of eight genes encoding sucrose synthase and two genes encoding beta-amylases was significantly upregulated in the transcriptome of cold-tolerant wheat, the sucrose content and soluble sugar content were also upregulated in cold-tolerant wheat under cold stress. Wang et al. [72] also found that the expression of SUS6, SPS1, AMY3 and BAM2 was significantly upregulated in the transcriptome of cold-tolerant Brassica campestris L. and the soluble sugar content was also upregulated under cold stress, meanwhile starch synthesis was not inhibited. In addition, Dong et al. [9] found that cold-tolerant cultivar of Poa pratensis under cold stress were able to accumulate more carbohydrates and had greater ROS scavenging ability compared with cold-sensitive cultivar. In our previous study, the sucrose content and soluble sugar content significantly increased in Dn1 under cold stress, and the ROS scavenging ability was also significantly higher than that of the weak cold-tolerant cultivar [29, 73]. In this study, the expression of genes encoding sucrose phosphate synthase (TraesCS6A02G144800), sucrose phosphate phosphatase (TraesCS5A02G002700 and TraesCS5D02G002500), sucrose synthase (TraesCS7A02G158900, TraesCS7B02G063400, TraesCS7D02G159800, TraesCS4A02G140000 and TraesCS4D02G169800), starch synthase (TraesCS7B02G018600 and TraesCS7D02G117800), alpha-amylase (TraesCS2B02G306400 and TraesCS3D02G248000) and beta-amylase (TraesCS1D02G218000) was upregulated under cold stress (Fig. 10). Changes in gene expression of starch and sucrose metabolism key enzymes in Dn1 may contribute to the accumulation of carbohydrates, thereby improve ROS scavenging ability under cold stress. In addition, the accumulation of soluble sugars may be at least partially triggered by starch degradation under cold stress [74]. In our previous study, the starch content in Dn1 decreased at -9 °C and subsequently increased at -18 °C [75]. This suggests that Dn1 is able to promptly replenish consumed starch under cold stress. The upregulated expression of starch synthase genes in our study may guarantee that starch synthesis is not inhibited when accumulating soluble sugars under cold stress. However, the specific mechanism needs further exploration.

We found many differentially expressed cold responsive genes through the Dn1 transcriptome. Among them, the expression patterns of carbohydrate metabolism key enzyme genes were consistent with the Dn1 physiological indexes changes in previous studies. However, their cold tolerance regulatory mechanism remains unclear. Further studies should explore the specific function of these key enzyme genes under cold stress. In addition, the regulatory mechanisms of some transcription factors, such as TaCBFIVd-A22, TabHLH3 and TaMYB4 also need further exploration, enriching the regulatory network of Dn1 under cold stress.

Conclusion

Our study is the first comprehensive analysis of the cold resistance mechanism of Dn1 at the transcriptional level via RNA-seq technology. The important genes involved in cold signal transduction were differentially expressed in Dn1 under cold stress. A large number of differentially expressed transcription factors belonging to the AP2/ERF, bZIP, NAC, WRKY, bHLH and MYB families were found under cold stress. However, only a few transcription factors were significantly up/downregulated under cold stress. Furthermore, some genes encoding key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism were upregulated under cold stress, suggesting that carbohydrate metabolism may be beneficial for improving plant cold tolerance. These results provide directions for further exploring the cold resistance mechanism of Dn1 and provide new ideas for breeding cold resistant crops.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and cold treatment

The tested winter wheat variety Dn1 was obtained from the Northeast Agriculture University Wheat Breeding Laboratory. Dn1 seeds were sown in a Northeast Agricultural University experimental field (45°7′ N, 126°6′ E) in Heilongjiang Province on September 10, 2019. The tillering nodes were then collected at 5 ℃ (October 1, 2019), 0 ℃ (November 1, 2019), -5 ℃ (November 10, 2019), -10 ℃ (November 18, 2019), -15 ℃ (November 28, 2019), -20 ℃ (December 24, 2019) and -25 ℃ (December 31, 2019) (average minimum temperature for ten consecutive days) and subsequently stored at -80 ℃. The field meteorological data during planting to the completion of sampling have been presented in Fig. S14.

mRNA library construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's procedure. The total RNA quantity and purity were analysed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 and RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent, CA, USA) with RNA integrity number > 7.0. Then, the cleaved RNA fragments were reverse-transcribed to create the final cDNA library in accordance with the protocol for the mRNA-Seq sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA), and the average insert size for the paired-end libraries was 300 bp (± 50 bp).

RNA sequencing and read mapping

We performed paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 (LC Sciences, USA) following the vendor’s recommended protocol. We aligned reads of all samples to the wheat reference genome (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/release-45/plants/fasta/triticum_aestivum/dna) using the HISAT package. HISAT allows multiple alignments per read (up to 20 by default) and a maximum of two mismatches when mapping the reads to the reference sequence. HISAT builds a database of potential splice junctions and confirms these by comparing the previously unmapped reads to the database of putative junctions.

Transcript abundance estimation and differential expression analysis

The mapped reads of each sample were assembled using StringTie. Then, all transcriptomes from samples were merged to reconstruct a comprehensive transcriptome using Perl scripts. After the final transcriptome was generated, StringTie and edgeR were used to estimate the expression levels of all transcripts. StringTie was used to determine the expression level of mRNAs by calculating FPKM. The differentially expressed mRNAs and genes were selected according to log2 (fold change) > 1 or log2 (fold change) < -1 and statistical significance (p value < 0.05) by edgeR.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

GO term enrichment of DEGs was analysed with the GO database (http://www.geneo ntology.org). The significantly enriched metabolic pathways of the DEGs were analysed with the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the plants using an Ultrapure RNA Kit (CWBIO, Jiangsu, China). cDNA was subsequently obtained from mRNA with a HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. TaACTIN was selected as an internal reference gene for wheat. The experimental results were analysed by the 2−ΔΔCT method. qRT-PCR analysis included three independent technical repeats with three biological replicates. The sequences of all the primers needed for the experiments are shown in Table S7.

Availability of data and materials

Raw Illumina sequence data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Upon publication, open access is available in the sequence read archive (SRA) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). The accession number is PRJNA787922 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA787922), which includes 21 accession items (SRR17227743-SRR17227763). All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Chinnusamy V, Zhu JK, Sunkar R. Gene regulation during cold stress acclimation in plants. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;639:39–55.

Jan N, Hussain MU, Andrabi KI. Cold resistance in plants: A mystery unresolved. Electron J Biotechn. 2009;12:1–15.

Shi YT, Ding YL, Yang SH. Molecular Regulation of CBF Signaling in Cold Acclimation. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23:623–37.

Lin QJ, Gao Y, Wu XX, Ni XY, Chen RZ, Xuan YH, Li TY. Evaluation of resistance to wheat stem rust and identification of resistance genes in wheat lines from Heilongjiang province. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10580.

Thomashow MF. PLANT COLD ACCLIMATION: Freezing Tolerance Genes and Regulatory Mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:571–99.

Ding YL, Shi YT, Yang SH. Advances and challenges in uncovering cold tolerance regulatory mechanisms in plants. New Phytol. 2019;222:1690–704.

Chattopadhyay MK. Mechanism of bacterial adaptation to low temperature. J Biosci. 2006;31:157–65.

Shi YT, Ding YL, Yang SH. Cold signal transduction and its interplay with phytohormones during cold acclimation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(1):7–15.

Dong WK, Ma X, Jiang HY, Zhao CX, Ma HL. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of Poa pratensis var anceps cv. Qinghai in response to cold stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):362.

Zhang F, Ji SJ, Wei BD, Cheng SC, Wang YJ, Hao J, Wang SY, Zhou Q. Transcriptome analysis of postharvest blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum ’Duke’) in response to cold stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):80.

Zhou HY, He Y, Zhu YS, Li MY, Song S, Bo WH, Li YY, Pang XM. Comparative transcriptome profiling reveals cold stress responsiveness in two contrasting Chinese jujube cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):240.

Ke LP, Lei WX, Yang WG, Wang JY, Gao JF, Cheng JH, Sun YQ, Fan ZX, Yu DL. Genome-wide identification of cold responsive transcription factors in Brassica napus L. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):62.

Dasgupta P, Das A, Datta S, Banerjee I, Tripathy S, Chaudhuri S. Understanding the early cold response mechanism in IR64 indica rice variety through comparative transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):425.

Liu YY, Wu C, Hu X, Gao HY, Wang Y, Luo H, Cai S, Li GW, Zheng YS, Lin CT, Zhu Q. Transcriptome profiling reveals the crucial biological pathways involved in cold response in Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Tree Physiol. 2020;40(4):538–56.

Jiang CJ, Zhang H, Ren JY, Dong JL, Zhao XH, Wang XG, Wang J, Zhong C, Zhao SL, Liu XB, Gao SB, Yu HQ. Comparative Transcriptome-Based Mining and Expression Profiling of Transcription Factors Related to Cold Tolerance in Peanut. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):1921.

Iquebal MA, Sharma P, Jasrotia RS, Jaiswal S, Kaur A, Saroha M, Angadi UB, Sheoran S, Singh R, Singh GP. RNAseq analysis reveals drought-responsive molecular pathways with candidate genes and putative molecular markers in root tissue of wheat. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13917.

Ma J, Zhang Y, Wang HG, Zhen WC, Li RQ. Differentially Expressed Genes and Enriched Pathways During Drought-Sensitive Period Under Field Conditions in Bread Wheat. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2019;37:389–400.

Zhao Y, Zhou M, Xu K, Li JH, Yang XJ. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide insights into cold stress response in wheat. Crop J. 2019;7(6):857–66.

Díaz ML, Soresi DS, Basualdo J, Cuppari SJ, Carrera A. Transcriptomic response of durum wheat to cold stress at reproductive stage. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(2):2427–45.

Aleliūnas A, Jakūn K, Statkeviiūt G, Vaitkeviiūt G, Armoniene R. Transcriptome changes triggered by a short-term low temperature stress in winter wheat. Zemdirbyste. 2020;107(4):329–36.

Kumar RR, Goswami S, Shamim M, Dubey K, Singh K, Singh S, Kala YK, Niraj RRK, Sakhrey A, Singh GP. Exploring the heat-responsive chaperones and microsatellite markers associated with terminal heat stress tolerance in developing wheat. Funct Integr Genomic. 2017;17(6):621–40.

Derakhshani B, Ayalew H, Mishina K, Tanaka T, Kawahara Y, Jafary H, Oono Y. Comparative Analysis of Root Transcriptome Reveals Candidate Genes and Expression Divergence of Homoeologous Genes in Response to Water Stress in Wheat. Plants. 2020;9(5):596.

Kruse EB, Carle SW, Wen N, Skinner DZ, Murray TD, Garland-Campbell KA, Carter AH. Genomic Regions Associated with Tolerance to Freezing Stress and Snow Mold in Winter Wheat. G3. 2017;7(3):775–80.

Lv Y, Song CH, Lu QW, Tian Y, Li HD, Zhang D, Yu J, Xu QH, Cang J. The Expression Characteristics of Transcription Factors Regulated by Exogenous ABA in Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum) under Cold Stress. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2018;65(6):842–8.

Tian Y, Peng KK, Bao YZ, Zhang D, Jing C. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase genes of winter wheat enhance the cold tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;161(3):86–97.

Peng KK, Tian Y, Jing C, Yu J, Tan YG. Overexpression of TaFBA-A10 from Winter Wheat Enhances Freezing Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021;41:314–26.

Yadav SK. Cold stress tolerance mechanisms in plants. A review Agron Sustain Dev. 2010;30(3):515–27.

Eremina M, Rozhon W, Poppenberger B. Hormonal control of cold stress responses in plants. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;73(4):1–14.

Bao YZ, Xing JP, Liang Y, Ren ZP, Fu LS, Yu J, Wang DJ, Zhang D, Xu QH, Cang J. Analysis of overwintering indexes of winter wheat in alpine regions and establishment of a cold resistance model. Field Crops Res. 2022;275:108347.

Knight MR, Knight H. Low-temperature perception leading to gene expression and cold tolerance in higher plants. New phytol. 2012;195(4):737–51.

Wilkins KA, Matthus E, Swarbreck SM, Davies JM. Calcium-Mediated Abiotic Stress Signaling in Roots. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1296.

Yuan P, Jauregui E, Du L, Tanaka K, Poovaiah BW. Calcium signatures and signaling events orchestrate plant-microbe interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;38:173–83.

Shi SJ, Li SG, Asim M, Mao JJ, Xu DZ, Ullah Z, Liu GS, Wang Q, Liu HB. The Arabidopsis Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases (CDPKs) and Their Roles in Plant Growth Regulation and Abiotic Stress Responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):1900.

Bai B, Wu J, Sheng WT, Zhou B, Zhou LJ, Zhuang W, Yao DP, Deng QY. Comparative Analysis of Anther Transcriptome Profiles of Two Different Rice Male Sterile Lines Genotypes under Cold Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):11398–416.

Li YS, Wang XR, Li Y, Zhang YJ, Gou ZW, Qi XS, Zhang JL. Transcriptomic Analysis Revealed the Common and Divergent Responses of Maize Seedling Leaves to Cold and Heat Stresses. Genes. 2020;11(8):881.

Almadanim MC, Alexandre BM, Rosa MTG, Sapeta H, Leitão AE, Ramalho JC, Lam TT, Negrão S, Abreu IA, Oliveira MM. Rice calcium-dependent protein kinase OsCPK17 targets plasma membrane intrinsic protein and sucrose-phosphate synthase and is required for a proper cold stress response. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(7):1197–213.

Lv XZ, Li HZ, Chen XX, Xiang X, Guo ZX, Yu JQ, Zhou YH. The role of calcium-dependent protein kinase in hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide and ABA-dependent cold acclimation. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(16):4127–39.

Liu Y, Xu CJ, Zhu YF, Zhang L, Chen TY, Zhou F, Chen H, Lin YJ. The calcium-dependent kinase OsCPK24 functions in cold stress responses in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2018;60(2):173–88.

Kumar K, Mosa KA, Chhikara S, Musante C, White JC, Dhankher OP. Two rice plasma membrane intrinsic proteins, OsPIP2;4 and OsPIP2;7, are involved in transport and providing tolerance to boron toxicity. Planta. 2014;239(1):187–98.

Sun T, Wang Y, Wang M, Li TT, Zhou Y, Wang XT, Wei SY, He GY, Yang GX. Identification and comprehensive analyses of the CBL and CIPK gene families in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:269.

Mao JJ, Manik SM, Shi SJ, Chao JT, Jin YR, Wang Q, Liu HB. Mechanisms and Physiological Roles of the CBL-CIPK Networking System in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 2016;7(9):62.

Yang T, Chaudhuri S, Yang L, Du L, Poovaiah BW. A calcium/calmodulin-regulated member of the receptor-like kinase family confers cold tolerance in plants. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7119–26.

Teige M, Scheikl E, Eulgem T, Dóczi R, Ichimura K, Shinozaki K, Dangl JL, Hirt H. The MKK2 pathway mediates cold and salt stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell. 2004;15(1):141–52.

Li H, Ding YL, Shi YT, Zhang XY, Zhang SQ, Gong ZZ, Yang SH. MPK3- and MPK6-Mediated ICE1 Phosphorylation Negatively Regulates ICE1 Stability and Freezing Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Dev cell. 2017;43(5):630–42.

Waititu JK, Cai Q, Sun Y, Sun Y, Li C, Zhang C, Liu J, Wang H. Transcriptome Profiling of Maize (Zea mays L.) Leaves Reveals Key Cold-Responsive Genes, Transcription Factors, and Metabolic Pathways Regulating Cold Stress Tolerance at the Seedling Stage. Genes. 2021;12(10):1638.

Cheng GM, Zhang LY, Wang HT, Lu JH, Wei HL, Yu SX. Transcriptomic Profiling of Young Cotyledons Response to Chilling Stress in Two Contrasting Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L) Genotypes at the Seedling Stage. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):5095.

Kawarazaki T, Kimura S, Iizuka A, Hanamata S, Nibori H, Michikawa M, Imai A, Abe M, Kaya H, Kuchitsu K. A low temperature-inducible protein AtSRC2 enhances the ROS-producing activity of NADPH oxidase AtRbohF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):2775–80.

Mehrotra S, Verma S, Kumar S, Kumari S, Mishra BN. Transcriptional regulation and signalling of cold stress response in plants: An overview of current understanding. Environ Exp Bot. 2020;180:104243.

Gilmour SJ, Zarka DG, Stockinger EJ, Salazar MP, Houghton JM, Thomashow MF. Low temperature regulation of the Arabidopsis CBF family of AP2 transcriptional activators as an early step in cold-induced COR gene expression. Plant J. 1998;16(4):433–42.

Wu PX, Li YC, Li XX, Liu WQ, Jun M, Lu TT, Nian SX, Jiang T. Differential Regulatory Mechanism of CBF Regulon Between Nipponbare(japonica) and 93–11(indica) During Cold Acclimation. Chin J Rice Sci. 2012;20(3):165–72.

Luo C, Liu H, Ren JN, Chen DL, Cheng X, Sun W, Hong B, Huang CL. Cold-inducible expression of an Arabidopsis thaliana AP2 transcription factor gene, AtCRAP2, promotes flowering under unsuitable low-temperatures in chrysanthemum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;146:220–30.

Badawi M, Danyluk J, Boucho B, Houde M, Sarhan F. The CBF gene family in hexaploid wheat and its relationship to the phylogenetic complexity of cereal CBFs. Mol Genet Genomics. 2007;277(5):533–54.

Sutton F, Chen DG, Ge X, Kenefick D. Cbf genes of the Fr-A2 allele are differentially regulated between long-term cold acclimated crown tissue of freeze-resistant and - susceptible, winter wheat mutant lines. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:34.

Fursova OV, Pogorelko GV, Tarasov VA. Identification of ICE2, a gene involved in cold acclimation which determines freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 2009;429(1–2):98–103.

Dong CH, Agarwal M, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Zhu JK. The negative regulator of plant cold responses, HOS1, is a RING E3 ligase that mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of ICE1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8281–6.

Miura K, Jin JB, Lee J, Yoo CY, Stirm V, Miura T, Ashworth EN, Bressan RA, Yun DJ, Hasegawa PM. SIZ1-mediated sumoylation of ICE1 controls CBF3/DREB1A expression and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(4):1403–14.

Lang ZB, Zhu JK. OST1 phosphorylates ICE1 to enhance plant cold tolerance. Sci China Life Sci. 2015;58(3):317–8.

Agarwal M, Hao Y, Kapoor A, Dong CH, Fujii H, Zheng X, Zhu JK. A R2R3 type MYB transcription factor is involved in the cold regulation of CBF genes and in acquired freezing tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(49):37636–45.

Pasquali G, Biricolti S, Locatelli F, Baldoni E, Mattana M. Osmyb4 expression improves adaptive responses to drought and cold stress in transgenic apples. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27(10):1677–86.

Vannini C, Locatelli F, Bracale M, Magnani E, Marsoni M, Osnato M, Mattana M, Baldoni E, Coraggio I. Overexpression of the rice Osmyb4 gene increases chilling and freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant J. 2004;37(1):115–27.

Li H, Yang Z, Zeng QW, Wang SB, Luo YW, Huang Y, Xin YC, He NJ. Abnormal expression of bHLH3 disrupts a flavonoid homeostasis network, causing differences in pigment composition among mulberry fruits. Hortic Res. 2020;7(1):83.

Kerepesi IlDiko, Galiba G. Osmotic and Salt Stress-Induced Alteration in Soluble Carbohydrate Content in Wheat Seedlings. Crop Sci. 2000;40(2):482–482.

Xu HX, Li XY, Chen JW. Comparative transcriptome profiling of freezing stress responses in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) fruitlets. J Plant Res. 2017;130(5):893–907.

Kinoshita J, Kawamori R. Gluconeogenesis and glycolysis. Nihon Rinsho. 2002;60(Suppl 7):121–8.

Gaete-Loyola J, Lagos C, Beltran MF, Valenzuela S, Emhart V, Fernandez M. Transcriptome profiling of Eucalyptus nitens reveals deeper insight into the molecular mechanism of cold acclimation and deacclimation process. Tree Genet Genomes. 2017;13(2):37.

Shen Q, Zhang SP, Liu SD, Chen J, Ma HJ, Cui ZQ, Zhang XM, Ge CW, Liu RH, Li Y, Zhao XH, Yang GZ, Song MZ, Pang CY. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Provides Insights into the Seed Germination in Cotton in Response to Chilling Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2067.

Zhang Q, Shan CH, Ning M, Zhao XX, Tang FX. Transcriptome Profiling of Gold Queen Hami Melons under Cold Stress. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2020;67(5):888–97.

Ramazan S, Qazi HA, Dar ZA, John R. Low temperature elicits differential biochemical and antioxidant responses in maize (Zea mays) genotypes with different susceptibility to low temperature stress. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2021;27(6):1395–412.

Wani UM, Majeed ST, Raja V, Wani ZA, Jan N, Andrabi KI, John R. Ectopic expression of a novel cold-resistance protein 1 from Brassica oleracea promotes tolerance to chilling stress in transgenic tomato. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16574.

Liu X, Chen L, Shi WL, Xu X, Li ZJ, Liu TF, He Q, Xie CH, Nie BH, Song BT. Comparative transcriptome reveals distinct starch-sugar interconversion patterns in potato genotypes contrasting for cold-induced sweetening capacity. Food chem. 2021;334:127550.

Jiang G, Hassan MA, Muhammad N, Arshad M, Chen X, Xu Y, Xu H, Ni QQ, Liu BB, Yang WK, Li JC. Comparative Physiology and Transcriptome Analysis of Young Spikes in Response to Late Spring Coldness in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:811884.

Wang CG, Zhang MY, Zhou JJ, Gao X, Zhu SD, Yuan LY, Hou XL, Liu TK, Chen GH, Tang XY, Shan GL, Hou JF. Transcriptome analysis and differential gene expression profiling of wucai (Brassica campestris L.) in response to cold stress. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):137.

Bao YZ, Yang N, Meng J, Wang D, Fu LS, Wang J, Cang J. Adaptability of winter wheat Dongnongdongmai 1 (Triticum aestivum L) to overwintering in alpine regions. Plant biol (Stuttg). 2021;23(3):445–55.

Huang X, Liang YS, Zhang BQ, Song XP, Li YR, Li CN, Qin ZQ, Li DW, Wei JG, Wu JM. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Potential Gene Modules Associated with Cold Tolerance in Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.). J Plant Growth Regul. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10437-9.

Liu LJ, Cang J, Yu J, Wang X, Huang R, Wang JF, Lu BW. Effects of Exogenous Abscisic Acid on Carbohydrate Metabolism and the Expression Levels of Correlative Key Enzymes in Winter Wheat under Low Temperature. Biosci Biotech Bioch. 2013;77(3):516–25.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Northeast Agriculture University Wheat Breeding Laboratory for providing the seeds of Dongnongdongmai1.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31971831). The funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT, KKP and JC designed research and analyzed the data; YT and KKP wrote the manuscript. GCL, ZPR and XZS consulted relevant literature. JPX, ZWW and CHS provided valuable suggestions on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was fully compliant with local and national regulations on plant usage.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Fig. S1. Correlation analysis between qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq data based on log2(fold change) of sixselected genes. Fig. S2. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_0 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S3. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_M5 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S4. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_M10 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S5. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_M15 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S6. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_M20 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S7. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the Tn_M25 vs. Tn_5 comparison group. The Y axis corresponds to KEGG pathway, the X axis shows the enrichment ratio between the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway. The color of the dot represents pvalue, and the size of the dot represents the number of DEGs mapped to the referent pathway. Fig. S8. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed bZIP transcription factors. Fig. S9. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed NAC transcription factors. Fig. S10. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed WRKY transcription factors. Fig.S11. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed bHLH transcription factors. Fig. S12. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed AP2/ERF transcription factors. Fig. S13. Expression pattern analysis of differentially expressed MYB transcription factors. Fig. S14. The field meteorological data during planting to completion of sampling. (A) Daily minimum and maximum temperatures (B) Daily precipitation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Y., Peng, K., Lou, G. et al. Transcriptome analysis of the winter wheat Dn1 in response to cold stress. BMC Plant Biol 22, 277 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03654-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03654-1