Abstract

Background

The health benefits of anthocyanins impel researchers and food producers to explorer new methods to increase anthocyanin contents in plant foods. Our previous studies revealed a positive role of nitric oxide (NO) in anthocyanin accumulation in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) sprouts. The application of hemin, an inducer of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), can effectively elevate NO production in vivo. Hemin treatment also improves plant growth and stress tolerance. This study is aimed to assess the effects of hemin treatment on anthocyanin production in radish sprouts, and to investigate whether NO signalling is involved in this process.

Results

The application of hemin significantly up regulated the expressions of many anthocyanins biosynthesis related structure and regulatory genes, leading to increased anthocyanins accumulation in radish hypocotyls. Hemin treatment also raised NO contents in radish sprouts, probably through enhancing nitrate reductase (NR) activity and Nitric Oxide-Associated 1 (NOA1) expression. Comparing the effects of Zinc Protoporphyrin (ZnPP, HO-1 activity inhibitor), Sodium Nitroprusside (SNP, NO donor) and carboxy-PTIO (cPTIO, NO-scavenger) on anthocyanin and NO production, a positive role of NO signalling has been revealed in hemin-derived anthocyanin accumulation. A positive feedback loop between HO-1 and NO may be involved in regulating this process.

Conclusions

Hemin induced anthocyanin accumulation in radish sprouts through HO-1 and NO signalling network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anthocyanins are a type of flavonoid pigments found in many plant foods, providing the red, orange, violet and blue colours for flowers, fruits, and leaves [1]. Plants produce anthocyanins as a protective mechanism against environmental stressors (ultraviolet light, cold temperatures, and drought) [2, 3] and biotic attack (herbivory and pathogen) [4, 5]. Moreover, flowers accumulate anthocyanins to attract pollinators and seed dispersers [6,7,8]. In addition to the roles in plants growth and development, anthocyanin have been demonstrated with many pharmacological benefits to human health, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, preventing age-related cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disease [9, 10]. Therefore, increasing anthocyanin concentration in fruit and vegetable could potentially promote human health.

The anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway is an extension of the general flavonoid pathway. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI) and flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H) are the key genes related to the general phenylpropanoid pathway. Therefore, these genes are involved in the biosynthesis of all downstream flavonoids, and generally be classified as early biosynthesis genes (EBGs). While late biosynthesis genes (LBGs) are specifically required for the biosynthesis of anthocyanins, such as dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (LDOX) and UDPglucose:flavonoid-3-O- glucosyltransferase (UF3GT) [11]. The expressions of these anthocyanin structural genes are conservatively controlled by the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) transcription factor complex [12, 13]. Two R2R3-MYB genes, Production of anthocyanin pigment1 (PAP1/MYB75, At1g56650) and PAP2 (MYB90, At1g66390), has been identified in Arabidopsis as positive regulators for the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes [14,15,16]. The PAP1 homologs in snapdragon, radish and cotton have also been revealed stimulating anthocyanin production [17,18,19].

Previous study in our group has revealed 0.5 mM sodium nitroprusside (SNP, a NO-releasing compound) application significant increased anthocyanin accumulation in radish sprout, along with enhanced endogenous NO levels [18]. Interestingly, an opposite phenotype has been reported in Lycium fruits during ripening, as the SNP supply and endogenous NO content negatively correlated with anthocyanin biosynthesis [20]. To further clarify the role of NO in anthocyanin production, we used hemin treatment in this study to induce the endogenous NO content. The effectiveness of hemin in trigger endogenous NO levels has been evidenced previously in cucumber and tomato lateral roots [21, 22]. As a heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) inducer, hemin application could improves plant stress tolerance in different plant species under various abiotic stress conditions [23,24,25]. Thus, hemin treatment has the potential to benefit plant growth, rather than to generate stress induced anthocyanin production.

We used cherry radish in the present study, as it is a nutritious and popular vegetable worldwide [26]. Moreover, with the red hypocotyls resulting from anthocyanin accumulation, radish sprouts could provide visual evidence for the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. Our results here suggested hemin could induce anthocyanin accumulation in plants through NO signalling pathway.

Results

Effects of hemin application on anthocyanin accumulation and endogenous NO production in radish sprouts

The anthocyanin contents in the hypocotyls of radish sprouts were examined after cultured with 1, 10, 25 and 50 μM hemin for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 1, significantly higher anthocyanin contents were observed in all hemin treated hypocotyls, along with enhanced NO levels, as compare to no-hemin control. However, the increase of anthocyanin was disproportionate to the raise of NO amount. Clearly, the anthocyanin biosynthesis in radish hypocotyl was highly sensitive to low level of hemin application, but quickly plateaued out when supplied with higher concentrations of hemin concentrations (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the endogenous NO contents exhibited a roughly linear increase by hemin applications up to 25 μM (Fig. 1C). The application of 50 μM hemin increased radish total fresh weight, shoot fresh weight and hypocotyl fresh weight (Fig. 1D-F).

Effects of hemin treatments on anthocyanin accumulation, NO production and fresh weight in radish sprouts. A The hypocotyl cross sections of radish sprout cultured with 0, 1, 10, 25 and 50 μM hemin supplements. Bar = 0.5 mm. B-C Anthocyanin content (B) and NO content (C) in radish hypocotyls after 0, 1, 10, 25 and 50 μM hemin treatments. D-F Total fresh weight (D), shoot fresh weight (E) and hypocotyl fresh weight (F) of radish sprouts after 0, 1, 10, 25 and 50 μM hemin treatments. The measurement resolution of the image was 3072*2304. The values were means ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

The effects of hemin treatment on the contents of different anthocyanin monomers were also assessed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). Among the different anthocyanin monomers, cyanidin 3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside was the main component in radish hypocotyls, which accounted for 64.4% of the total anthocyanin, followed by cyanidin 3-O-xylosyl-rutinoside (11.2%), pelargonidin 3-O-glucosyl-glucoside (7.4%), peonidin 3-O-coumaroylglucoside-5-O-glucoside (5.4%) and pelargonidin 3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside (3.6%), and others only made up to less than 8% of the total anthocyanin contents (Fig. 2). 10 μM hemin treatment exhibited a ~ 30% higher total anthocyanin level, mainly attributed to the 19.1%, 87.4%, 21.5% and 132.8% increases of cyanidin 3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, pelargonidin 3-O-glucosyl-glucoside, pelargonidin 3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside and petunidin 3-O-rutinoside respectively (Fig. 2). In contrast, the amounts of cyanidin 3-O-sophoroside, pelargonidin 3-O-galactoside, cyanidin 3-O-(6’’-caffeoyl-glucoside) were significantly reduced in hemin cultured radish hypocotyls (Fig. 2). The adjusted monomer proportions probably led to the slight colour changes of the hypocotyl cross sections shown in Fig. 1A.

Effects of hemin treatment on the contents and proportions of anthocyanin monomers. The relative contents of anthocyanin monomers were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Asterisk indicates significant difference between control (no hemin) and hemin (10 μM) treatments (P < 0.05)

Effects of NO on anthocyanin contents in hypocotyls of radish sprouts

To further investigate the effect of NO on anthocyanin accumulation in the radish hypocotyls, Sodium Nitroprusside (SNP, an exogenous NO donor) and carboxy-PTIO (cPTIO, a specific NO-scavenger) were then used. As shown in Fig. 3A, 10, 50, 100, 200 and 1000 μM SNP applications significantly enhanced anthocyanin contents, with the highest amount achieved by 200 μM SNP treatment. On the other hand, 50, 100, 200 and 1000 μM cPTIO treatments significantly decreased anthocyanin contents in radish hypocotyls, with the lowest anthocyanin level detected by 200 μM cPTIO treatment (Fig. 3B). Taken together, anthocyanin accumulation in hypocotyls positively correlated with NO production at low to medium levels, whereas high level NO exposure could suppress anthocyanin accumulation.

Radish hypocotyl anthocyanin contents in response to SNP (A) and cPTIO (B) application. Total anthocyanin contents were represented as means ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

The relationship of nitric oxide and hemin in anthocyanin induction

The biological effects of hemin application have been largely attributed to its induction of HO-1 in vivo [27, 28]. To test if the role of hemin in anthocyanin accumulation was related to NO production, Zinc (II) Protoporphyrin IX (ZnPP) was used, due to its specific role in HO-1 activity inhibition. ZnPP has been well documented in medical research able to reverse the effects of hemin. In human monocytes, Hemin inhibits apoptosis, while ZNPP reverses this effect. Hemin also promoted the formation of adventitious roots in cucumber explants in a dose-dependent manner, while treatment with Znpp resulted in a significant reduction in hemin-induced adventitious roots [29,30,31]. Compare to control, ZnPP treatment significantly decreased anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 4), indicated a positive correlation between HO-1 activity and anthocyanin content. If hemin increase anthocyanin content through promoting NO production, we may expect the suppression of anthocyanin content by ZnPP could be abolished by the SNP application. Indeed, ZnPP + SNP treatment significantly increased anthocyanin levels in radish hypocotyls (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the co-application of ZnPP and ePTIO led to an even lower level of anthocyanin, as compare to single chemical treatments (Fig. 4), implying hemin and NO may act addictively in anthocyanin accumulation in radish hypocotyls.

Effects of hemim, ZnPP, SNP, cPTIO and their combinations on anthocyanin accumulation in radish hypocotyls. A Representative images of the hypocotyl cross sections (top) and the hypocotyls (bottom), bars = 0.5 mm in cross section, and 1.0 mm in hypocotyls. B The anthocyanin contents in radish hypocotyls under different treatments. The measurement resolution of the image was 3072*2304. Data represented in mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

Expression of anthocyanin-related biosynthesis structural and regulatory genes under different treatments

To explore the molecular basis of the hemin and NO in anthocyanin accumulation, we then tested the expression levels of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related structural and regulatory genes in the hypocotyls of radish sprouts. 8 families of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes were identified from radish hypocotyl transcriptome data (obtained in our previous studies). The members and their expression levels were listed in Supplemental Table 1. For F3H, DFR, ANS, LDOX and UFGT, the gene with the highest FPKM value in each family was chose for further expression. For PAL, CHI and CHS, several genes shown relatively high FPKM values. The transcription levels of the top three members in each family were then verified by RT-qPCR (Supplemental Fig. 1), and the dominant genes were chosen for further experiment in response to different chemical treatments.

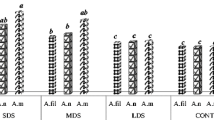

As shown in Fig. 5, PAL is the only EBG gene stimulated by hemin supply; ZnPP treatment reduced CHS and F3H transcription; SNP application increased the expressions of three EBGs PAL, CHI and F3H; while the transcripts of all four tested EBGs remained similar abundances after cPTIO treatment. In contrast, hemin and SNP treatments significantly up regulated the transcriptions of all tested anthocyanin LBGs (DFR, ANS, UF3GT, LGOX); whereas ZnPP and cPTIO treatments had no effects on these LBGs expression levels in radish hypotocyls (Fig. 5). Moreover, hemin + SNP significantly enhanced the transcriptions of all eight tested anthocyanin biosynthesis-related structure genes; ZnPP + cPTIO suppressed the expressions of EBGs and LDOX (Fig. 5). Notably, hemin + cPTIO successfully abolished the activation of LBG transcriptions by hemin, indicating hemin may act through NO signalling in regulating these anthocyanin biosynthesis genes; while SNP + ZnPP treatment decreased LBG expressions as compare to SNP-only, suggesting an opposite signalling pathway as HO-1 activity may be required for NO to exert its role (Fig. 5). Together, these results implied a crosstalk between HO-1 and NO signalling in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Effects of hemin, ZnPP, SNP and cPTIO on the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related structural genes. The expression level of A PAL, B CHS, C CHI, D F3H, E DFR, F ANS, G UF3GT and H LDOX. Each gene here was the dormant member in corresponding gene family. Expression levels were represented in means ± SD of three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

In addition, hemin and SNP treatments greatly stimulated the transcriptional levels of two radish PAP homologs, PAP1 and PAP2, in radish hypocotyls (Fig. 6). Noteworthily, the hemin + SNP treatment gave rise to a dramatic raise of PAP1 expression (3.6 folds of that in control). Compare with the 128% and 124% increasements of PAP1 transcripts by hemin-only and SNP-only respectively, these two chemicals may act synergistic in stimulating PAP1expression, and thereby the biosynthesis of anthocyanin. However, hemin + SNP application resulted less PAP2 transcripts than hemin-only or SNP-only treatments, implying a different regulatory pattern of hemin and NO signalling in modifying PAP2 expression.

NO content, NO biosynthesis-related enzymes activities and gene expression under various chemical treatments

To further investigate the relationship between hemin and endogenous NO production, we tested the NO contents in response to the chemical treatments as above. Using the specific NO fluorescent probe, 4-Amino-5-methylamino- 2’,7’-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM DA), NO signals were detected mainly in the stele tissues of radish hypocotyls (Fig. 7A). Compare to control, hemin, SNP, hemin + SNP, ZnPP + SNP treatments significantly increased NO contents, whereas ZnPP, cPTIO and ZnPP + cPTIO suppressed the NO levels in radish hypocotyls (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, ZnPP + SNP treatment caused a small induction of NO in compare to control, but still significantly lower than that of SNP-only; moreover, hemin + SNP generated higher NO level than hemin or SNP only (Fig. 7C). Hence, consistently, HO-1 activity was probably involved in SNP-derived NO production.

The NO contents in the radish hypocotyls in response to different treatments. A Representative fluorometric images of the radish hypocotyl cross sections stained by NO specific tracer DAF FM-DA after according chemical treatments. Bar = 50 μm. B A representative bright field image of the radish hypocotyl cross section. C The NO contents in the hypocotyls of radish sprouts measured by nitrate reductase method. The measurement resolution of the image was 1388*1044. The values were means ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

Subsequently, we measured the activities of two key enzymes as well as the expression levels of NO biosynthesis-associated genes. Nitrate reductase (NR) reduces nitrate to nitrite using electrons from NAD(P)H, and also lead to NO production from nitrite due to its nitrite reductase activity [32, 33]. While nitric oxide synthases (NOS) catalyzing the production of nitric oxide (NO) from L-arginine. As shown in Fig. 8A, hemin, SNP and hemin + SNP cultured radish hypocotyls presented higher NR activities than control treatment. However, the activity of NOS was only slightly increased in hemin + SNP treatment (Fig. 8B). In addition, higher abundance of NIA1 (Nitrate reductase [NADH]) transcripts were detected by SNP supplication, while hemin and SNP promoted the expression levels of NOA1 (Nitric oxide associated factor; a putative NOA1 homolog gene identified in radish transcriptome according to the Arabidopsis NOA1 gene sequence) in radish hypotocyls (Fig. 7C). Together, the activities of key enzymes and the transcription levels of the related genes encoding were roughly correlated with the endogenous NO levels in the different chemical treatments, confirmed the positive role of hemin and SNP in NO production.

Effects of different treatments on the activities of key NO biosynthesis enzymes and encoding genes. A and B The enzyme activities of NR (A) and NOS (B) in radish hypocotyls. C and D The relative expression levels of NIA1 (C) and NOA1 (D) in radish hypocotyls. RsActin was used as internal control. The values were means ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05)

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to test the effects of hemin application in anthocyanin induction, and to investigate whether NO signalling is involved in this process. As expected, hemin treatment enhanced anthocyanin accumulation in the hypocotyls of radish sprouts (Figs. 1 and 4). At transcriptional level, hemin application promoted the expressions of anthocyanin biosynthesis structure genes (especially the LBGs, Fig. 5), as well as two R2R3-MYB transcription factors (RsPAP1 and RsPAP2, Fig. 6), which probably act as positive regulatory in anthocyanin biosynthesis same as their Arabidopsis homologs. Notably, the anthocyanin level was significantly increased by low level hemin application (33% higher anthocyanin content at 1 μM hemin as compare to no hemin control), however, further increasing hemin concentrations to 10 μM and 25 μM had much smaller effects on anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 1). The induction of anthocyanins in vegetative tissues is often considered to be a response of plants to biotic or abiotic stress conditions [34, 35]. It is reasonable that the accumulation of anthocyanins in these tissues should be tightly regulated, to avoid unnecessary anthocyanin production due to pleiotropy, meanwhile to maintain some degree of freedom [36]. In this study, the radish seedlings were grown under optimal conditions, and the addition of hemin in the culture system had no negative effect on seedling growth. It makes sense that the increase of anthocyanin by hemin treatments was retained at reasonable levels. Hence, for health benefits, the anthocyanin contents in radish sprouts could be elevate to a certain level by hemin treatment, although a further boost would be challenging. In addition, the proportions of anthocyanin monomers were changed after hemin treatments (Fig. 2). Future studies to identify the specific biosynthesis and regulatory pathways of desired monomers would be useful for bioengineering purpose.

Besides anthocyanin, hemin applications also increased the endogenous NO levels in radish hypocotyls (Figs. 1 and 6). As a well-known HO-1 inducer, hemin induces NO production through HO-1/CO signal transduction [37]. Hemin-induced NO production has been documented in various biological processes, such as wheat endosperm development [38], tomato, rice and cucumber rooting process [22, 37, 39] and sunflower seedling growth in response to salt stress [40]. To explore the involvement of this hemin-induced NO production in anthocyanin accumulation, we compared the effects of SNP (NO donors), cPTIO (NO scavenger) and ZnPP (HO-1 inhibitor) along with hemin treatment. SNP and cPTIO applications positively and negatively regulated anthocyanin accumulation in radish hypocotyls (Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6). Supply cPTIO together with hemin (hemin + cPTIO) significantly reduced anthocyanin and NO productions, as compare to those in hemin-only treatment (Figs. 3 and 7), confirmed the contribution of NO in hemin-derived anthocyanin accumulation. Thus, hemin (HO-1 inducer) probably increases anthocyanin production via HO-1/CO–NO signalling crosstalk. Of course, more experiments are required to confirm the increase of in vivo HO-1 activity by hemin feeding.

Interestingly, ZnPP displayed an inhibitory role in SNP-generated NO production and anthocyanin accumulation (Figs. 4, 7 and 8), suggesting an involvement of HO-1 activity in NO biosynthesis in vivo. One possible explanation is that NO may generate a signal to positively regulate HO-1 production, while restricting HO-1 activity blocks the positive feed-back loop, and therefore reduced NO and anthocyanin productions. NO-mediated HO-1 induction has been reported in many medical research studies, such as in vascular smooth muscle cell function [41] and in regulating murine macrophage-like cell line J774.1/JA-4 [42]. Obviously, future studies are required to test this hypothesis in radish sprouts and other plant systems.

By enhancing the HO-1 activity, hemin promotes cellular heme degradation to bliverdin (BV), carbon monoxide (CO) and ferrous iron (Fe2+) It would be interesting to test whether these endogenous products of hemin, BV, Fe2+ and CO also involved in this hemin-induced anthocyanin accumulation in the future studies.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study suggested hemin application could act through NO signalling in stimulating anthocyanin accumulation in the hypocotyls of radish sprout. The possible molecular mechanism is proposed as Fig. 9. Hemin, as a HO-1 inducer, could up regulate the expression of NIA1 and NOA1 gene, enhance NR and NOS activities, and thereby promote NO production. NO may induce HO-1 gene expression to form a positive feedback loop with HO-1. NO signalling also stimulates the expressions of anthocyanin biosynthesis related regulatory R2-R3 MYB transcription factors (PAP1 and PAP2) and structural genes (PAL, DFR, ANS, LDOX and UF3GT), leading to higher anthocyanin accumulation.

A model of how hemin induce anthocyanin accumulation in the hypocotyls of radish sprouts. Hemin probably act as a HO-1 inducer to increase NIA and NOA1 gene expression and enhance NR and NOS activities, and thereby promotes NO production. NO may induce HO-1 heme oxygenase-1 gene expression (as revealed in human muscle cell line and murine macrophage-like cell line) to form a positive feedback loop with HO-1. NO signalling probably up regulates the expression of transcription factors (PAP1 and PAP2), which could activate the transcriptions of anthocyanin biosynthesis related structural genes, and lead to anthocyanin accumulation. The measurement resolution of the image was 1388*1044. Bar = 50 μm

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Raphanus Sativus (L.) cv. Yanghua seeds were purchased in Nanjing Wanbang Seed Industry Co., Ltd. The seeds were soaked in distilled water for 8 h and placed on moist gauze for germination for 24 h in dark at 25 ± 2℃. Uniform-sized seedlings were transferred into petri dish with two layers of moist filter paper, grown for 36 h in the dark. Seedlings were then cultured with according chemical solutions or deionized water (as control) in a growth incubator (Ningbo Haishu Safe Instrument Experimental Factory, Zhejiang, China) under LED white light (red ratio 14.1%, green ratio 81.3%, blue ratio 4.6%) for 48 h (50 ± 5 μmol·m−2·s−1 light intensity,80% relative humidity, 25 ± 2℃). The chromaticity parameters were measured by Spic-200 spectral color illuminance meter. Hemin, ZnPP, SNP and cPTIO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (China). For control set, 5 mL deionized water or corresponding chemicals was added into the petri dish every 12 h. The hypocotyls of the seedlings were then harvested for measurement in different experiments.

Observation of hypocotyl cross section of Radish sprout

Radish hypocotyls were hand sectioned. The hypocotyl cross sections were visualized under a stereomicroscope (Model Stemi 2000-C; Carl Zeiss, Germany), and photographed using a digital camera (Powershot A620, Canon Photo Film, Japan, The measured resolution was 3072*2304).

Anthocyanin content measurement

Total anthocyanin content was measured according to [43] with modification. 0.5 g fresh hypocotyls were immersed in 1% methanol hydrochloride for 24 h in the dark. The extraction solvents were then centrifuged at 5,000 g for 10 min at 4℃. The supernatants were measured by a spectrophotometry (UV-5200 spectrophotometer; Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd, China). The absorbances at 530 nm and 657 nm were used for anthocyanin content determination, using the following formular: Anthocyanin content (U·g−1FW) = (A530-A657 × 0.25) /Fresh weigh.

Determination of anthocyanin monomer contents

The contents of anthocyanin monomers were determined using UPLC-MS according to [44]. 2 g fresh hypocotyl samples were grounded in liquid nitrogen and put in a 10 mL centrifuge tube containing 5 mL 0.1% acetic acid–methanol (V/V) solution for 12 h in dakness. Then the tubes with mixture were centrifuged at 14,500 g at 4℃ for 10 min, and 5 mL of supernatant was taken out and last evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator (LNG-T120, Taicang Hualida Laboratory Equipment Co., Ltd, Taichang, China). Add 200 μL 80% methyl alcohol (V/V) into the tubes to dissolve the dryness and then filtered with 0.22 μm regenerated cellulose filter before LC–MS/MS measurement.

The samples were analyzed by LC–MS system (G2-XS QTof, Waters). 2 μL solution was injected into the UPLC column (2.1 × 100 mm ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column containing 1.7 μm particles) with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Buffer A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water, and buffer B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The gradient was 5% Buffer B for 1 min, 5–95% Buffer B for 11 min, 95% Buffer B for 2 min. Mass spectrometry was performed using electrospray source in positive ion mode with MS acquisition mode, with a selected mass range of 50–1200 m/z. The lock mass option was enabled using leucine-enkephalin (m/z 556.2771) for recalibration. The ionisation parameters were the following: capillary voltage was 3.0 kV, cone voltage was 30 V, source temperature was 120 °C, and desolvation gas temperature was 400 °C. Collision energy was 20–40 eV. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Masslynx 4.1. Extraction of centroid spectra peaks with a width of 0.01 Da was used to determine the extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) from the total ion chromatogram (TIC). The data were processed by Xcalibur software, and the content of anthocyanin monomer was represented by the peak area of the sample.

NO quantification

Radish hypocotyls (0.5 g) were averagely homogenized with 4 mL of 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.2), and then the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 g at 4 ℃. The supernatant was gathered and tested in an A012 Nitric Oxide (NO) assay kit (Nitrate reductase method) (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Jiangsu, China). Fluorescent tracer DAF-FM-DA (3-Amino,4-aminomethy1-2’, 7’difluorescein, diacetate) were used to quantify the NO levels in radish sprout hypocotyls. The hypocotyls were hand sectioned to ~ 1 mm thickness, washed with PBS buffer (PH7.4) for three times, and then incubated with 5 μM DAF-FM DA in dark for 20 min. The samples were then washed with PBS (PH7.4) three times (10 min each time) to fully remove the surface dye. Zess Imager M2 fluorescence microscope was used for observation and photographing (The measured resolution was 1388*1044). Fluroescent signals were detected using the excitation wavelength of 495 nm, and the emission wavelength of 515 nm. The relative fluorescence intensity was calculated by Axio Vison Rel.4.8.

Determination of NR and NOS activities

The enzyme activity of NR and NOS was detected by nitrate reductase assay kit and total nitric oxide synthase assay kit (purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering). Before detecting the NR enzyme activity, the cleaned hypocotyls were soaked in the induction solution for 2 h, and then dried with filter paper and stored at -20℃ for 30 min. The total protein was extracted according to the [45]. The NR and NOS activities according to the instruction manual for determination.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Freshly harvested radish hypocotyls (100 mg) were adequately ground to powder with liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) following manufacturer’s instruction, and finally dissolved in 50 μl RNase-free water. The extracted RNA was disposed with DNase I (RNase-free, Transgen®) at 25 °C for 30 min, followed by performance of reverse transcription according to the manufacturer’s instruction (TransScript® First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix, Transgen®). The qRT-PCR reactions were manipulated by utilizing a Mastercycler®ep realplex real-time PCR system (ABI7500, MD, USA) with Bestar® SybrGreen qPCR mastermix (DBI, Bioscience Inc.,Germany) in a 20 μL reaction volume. The primers as shown in Table S2.

Statistical analyses

Microsoft Office Excel 2016 was used to organize and process the data. Originpro 2016 was used to create the plots. SPSS statistical software installation package (version 11.0) was used to calculate the p value and tested for significant differences. The values are means ± standard deviation (SD) of the three independent experiments with at least three replicates for each. Differences among treatments were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) integrated with Duncan’s multiple range test, with P < 0.05 as the threshold.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NR:

-

Nitrate reductase

- NOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- NOA1:

-

Nitric oxide associated 1

- EBGs:

-

Early biosynthesis genes

- PAL:

-

Phenylalanine ammonia lyase

- CHS:

-

Chalcone synthase

- CHI:

-

Chalcone isomerase

- F3H:

-

Flavanone-3-hydroxylase

- LBGs:

-

Late biosynthesis genes

- DFR:

-

Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase

- ANS:

-

Anthocyanidin synthase

- LDOX:

-

Leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase

- UF3GT:

-

UDPglucose flavonoid-3-O- glucosyltransferase

- PAP1:

-

Production of anthocyanin pigment1

- PAP2:

-

Production of anthocyanin pigment2

- cPTIO:

-

Carboxy-PTIO

- ZNPP:

-

ZincProtoporphyrin

- SNP:

-

Sodium Nitroprusside

- NIA:

-

(Nitrate reductase [NADH])

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- HO-1:

-

Heme oxygenase-1

References

Albert NW, Davies KM, Lewis DH, Zhang HB, Montefiori M, Brendolise C, Boase MR, Ngo H, Jameson PE, Schwinn KE. A Conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in Eudicots. Plant Cell. 2014;26(3):962–80.

Zhang Q, Zhai J, Chen G, Lin W, Peng C. The changing distribution of anthocyanin in Mikania Micrantha leaves as an adaption to low-temperature environments. Plants (Basel). 2019;8(11):456.

Outchkourov NS, Karlova R, Holscher M, Schrama X, Blilou I, Jongedijk E, Simon CD, van Dijk ADJ, Bosch D, Hall RD, Beekwilder J. Transcription factor-mediated control of anthocyanin biosynthesis in vegetative tissues. Plant Physiol. 2018;172(2):1862–78.

Karageorgou P, Manetas Y. The importance of being red when young: anthocyanins and the protection of young leaves of quercus coccifera from insect herbivory and excess light. Tree Physiol. 2006;26(5):613–21.

Sun X-h, Zhou T-t, Wei C-h, Lan W-q, Zhao Y, Pan Y-j, Wu VCH. Antibacterial effect and mechanism of anthocyanin rich Chinese wild blueberry extract on various foodborne pathogens. Food Control. 2018;94:155–61.

Mol J, Grotewold E, Koes R. How genes paint flowers and seeds. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3(6):212–7.

Stuurman J, Hoballah ME, Broger L, Moore J, Basten C, Kuhlemeier C. Dissection of floral pollination syndromes in petunia. Genetics. 2004;168(3):1585–99.

Petroni K, Tonelli C. Recent advances on the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in reproductive organs. Plant Sci. 2011;181(3):219–29.

Zhang HY, Xu ZL, Zhao HW, Wang X, Pang J, Li Q, Yang Y, Ling WH. Anthocyanin supplementation improves anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory capacity in a dose-response manner in subjects with dyslipidemia. Redox Biol. 2020;32:101474.

Pojer E, Mattivi F, Johnson D, Stockley CS. The case for anthocyanin consumption to promote human health: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 2013;12(5):483–508.

Pelletier MK, Murrell JR, Shirley BW. Characterization of flavonol synthase and leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase genes in Arabidopsis - further evidence for differential regulation of “early” and “late” genes. Plant Physiol. 1997;113(4):1437–45.

Baudry A, Heim MA, Dubreucq B, Caboche M, Weisshaar B, Lepiniec L. TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of banyuls and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2004;39(3):366–80.

Koes R, Verweij W, Quattrocchio F. Flavonoids: a colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(5):236–42.

Borevitz JO, Xia YJ, Blount J, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2000;12(12):2383–93.

Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Leavitt JM, Lloyd AM. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2008;53(5):814–27.

Tohge T, Nishiyama Y, Hirai MY, Yano M, Nakajima JI, Awazuhara M, Inoue E, Takahashi H, Goodenowe DB, Kitayama M, et al. Identification of genes involved in anthocyanin accumulation by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome in PAP1-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. In: Nikolau BJ, Wurtele ES (eds) Concepts in Plant Metabolomics, Springer, Heidelberg, pp 159-168.

Schwinn KE, Boase MR, Bradley JM, Lewis DH, Deroles SC, Martin CR, Davies KM. MYB and bHLH transcription factor transgenes increase anthocyanin pigmentation in petunia and lisianthus plants, and the petunia phenotypes are strongly enhanced under field conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:603.

Wu Q, Su NN, Zhang XY, Liu YY, Cui J, Liang YC. Hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide and UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 interact to mediate UV-B-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in radish sprouts. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1.

Li X, Ouyang XF, Zhang ZS, He L, Wang Y, Li YH, Zhao J, Chen Z, Wang CN, Ding LL, Pei Y, Xiao YH. Over-expression of the red plant gene R1 enhances anthocyanin production and resistance to bollworm and spider mite in cotton. Mol Genet Genom. 2019;294(2):469–78.

Li G, Qin B, Li S, Yin Y, Zhao J, An W, Cao Y, Mu Z. LbNR-derived nitric oxide delays lycium fruit coloration by transcriptionally modifying flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1215.

Liu Y, Xu S, Ling T, Xu L, Shen W. Heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide system participates in regulating wheat seed germination under osmotic stress involving the nitric oxide pathway. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167(16):1371–9.

Li JL, Zhu D, Wang R, Shen WB, Guo YY, Ren Y, Shen W. Huang LQ:beta-Cyclodextrin-hemin complex-induced lateral root formation in tomato: involvement of nitric oxide and heme oxygenase 1. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34(3):381–93.

Zilli CG, Balestrasse KB, Yannarelli GG, Polizio AH, Santa-Cruz DM, Tomaro ML. Heme oxygenase up-regulation under salt stress protects nitrogen metabolism in nodules of soybean plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2008;64(1):83–9.

Yannarelli GG, Noriega GO, Batlle A, Tomaro ML. Heme oxygenase up-regulation in ultraviolet-B irradiated soybean plants involves reactive oxygen species. Planta. 2006;224(5):1154–62.

Xu S, Lou TL, Zhao N, Gao Y, Dong LH, Jiang DJ, Shen WB, Huang LQ, Wang R. Presoaking with hemin improves salinity tolerance during wheat seed germination. Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33(4):1173–83.

Hanlon PR, Barnes DM. Phytochemical composition and biological activity of 8 varieties of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) sprouts and mature taproots. J Food Sci. 2011;76(1):C185–92.

Privitera MG, Potenza M, Bucolo C, Leggio GM, Drago F. Drago F:Hemin, an inducer of heme oxygenase-1, lowers intraocular pressure in rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23(3):232–9.

Su NN, Niu MY, Liu Z, Wang L, Zhu ZB, Zou JW, Chen YH, Cui J. Hemin-decreased cadmium uptake in pak choi (Brassica chinensis L.) seedlings is heme oxygenase-1 dependent and relies on its by-products ferrous iron and carbon monoxide. Environ Pollut. 2021;274:115882.

Xuan W, Zhu FY, Xu S, Huang BK, Ling TF, Qi JY, Ye MB, Shen WB. The heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide system is involved in the auxin-induced cucumber adventitious rooting process. Plant Physiol. 2008;148(2):881–93.

Lang D, Reuter S, Buzescu T, August C, Heidenreich S. Heme-induced heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in human monocytes inhibits apoptosis despite caspase-3 up-regulation. Int Immunol. 2005;17(2):155–65.

Metz R, DuHadaway JB, Rust S, Munn DH, Muller AJ, Mautino M, Prendergast GC. Zinc protoporphyrin IX stimulates tumor immunity by disrupting the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(6):1864–71.

Yamasaki H, Sakihama Y. Simultaneous production of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite by plant nitrate reductase: in vitro evidence for the NR-dependent formation of active nitrogen species. Febs Lett. 2000;468(1):89–92.

Yamasaki H, Sakihama Y, Takahashi S. An alternative pathway for nitric oxide production: new features of an old enzyme. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4(4):128–9.

Chalker-Scott L. Environmental significance of anthocyanins in plant stress responses. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70(1):1–9.

Landi M, Tattini M, Gould KS. Multiple functional roles of anthocyanins in plant–environment interactions. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;119:4–17.

LaFountain AM, Yuan YW. Repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021;231(3):933–49.

Xuan W, Xu S, Li MY, Han B, Zhang B, Zhang J, Lin YT, Huang JJ, Shen WB, Cui J. Nitric oxide is involved in hemin-induced cucumber adventitious rooting process. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(11):1032–9.

Wu MZ, Huang JJ, Xu S, Ling TF, Xie YJ, Shen WB. Haem oxygenase delays programmed cell death in wheat aleurone layers by modulation of hydrogen peroxide metabolism. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(1):235–48.

Chen YH, Chao YY, Hsu YY, Hong CY, Kao CH. Heme oxygenase is involved in nitric oxide- and auxin-induced lateral root formation in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31(6):1085–91.

Singh N, Bhatla SC. Nitric oxide and iron modulate heme oxygenase activity as a long distance signaling response to salt stress in sunflower seedling cotyledons. Nitric Oxide Biol Chem. 2016;53:54–64.

Durante W, Kroll MH, Christodoulides N, Peyton KJ, Schafer AI. Nitric oxide induces heme oxygenase-1 gene expression and carbon monoxide production in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1997;80(4):557–64.

Koike A, Minamiguchi I, Fujimori K, Amano F. Nitric oxide is an important regulator of ileme oxygenase-1 expression in the lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma-treated murine macrophage-like cell line J774.1/JA-4. Biol Pharm Bull. 2015;38(1):7–16.

Zhou B, Zhang Z, Wang XH. Anthocyanin-rich maize purple plant pigment stimulated the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic Mc3t3-E1 cells. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63:1148–9.

Su N, Wu Q, Liu Y, Cai J, Shen W, Xia K, Cui J. Hydrogen-rich water reestablishes ROS homeostasis but exerts differential effects on anthocyanin synthesis in two varieties of radish sprouts under UV-A irradiation. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(27):6454–62.

Lin AH, Wang YQ, Tang JY, Xue P, Li CL, Liu LC, Hu B, Yang FQ, Loake GJ, Chu CC. Nitric oxide and protein S-nitrosylation are integral to hydrogen peroxide-induced leaf cell death in rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(1):451–64.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(21)3034) and Jiangsu Seed industry revitalization project (JBGS[2021]004). Funders were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS performed some experiments and wrote the manuscript. ZL performed supplemental experiments and analyze the data. LW made the figures and revised the manuscript. YL performed some experiments. MN developed illustration in the paper and revised the manuscript. XC and JC designed and conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The expressions of the key PAL, CHI and CHS key genes in radish hypocotyls. Table S1.The expression levels of anthocyanin biosynthesis related structure genes. Table S2.The nucleotide sequence of primers used in the qRT-PCR.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, N., Liu, Z., Wang, L. et al. Improving the anthocyanin accumulation of hypocotyls in radish sprouts by hemin-induced NO. BMC Plant Biol 22, 224 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03605-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03605-w