Abstract

Background

The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau is experiencing rapid climate warming, which may further affect plant growth. However, little is known about the plant physiological response to climate change.

Results

Here, we select the Kobresia pygmaea, an important perennial Cyperaceae forage, to examine the physiological indices to temperature changes in different growing months. We determined the contents of malondialdehyde, proline, soluble sugars, superoxide dismutase, peroxidation, and catalase activity in leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea at 25℃, 10℃, 4℃ and 0℃ from June to September in 2020. The results showed that the content of osmotic adjustment substances in the leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea fluctuated greatly with experimental temperature in June and September. The superoxide dismutase activity in the leaves and roots of the four months changed significantly with temperatures. The peroxidation activity in the leaves was higher than that in the roots, while the catalase activity in leaves and roots fluctuates greatly during June, with a relative stable content in other months. Membership function analysis showed that higher temperatures were more harmful to plant leaves, and lower temperatures were more harmful to plant roots. The interaction of organs, growing season and stress temperature significantly affected the physiological indicators.

Conclusions

The physiological indicators of Kobresia pygmaea can actively respond to temperature changes, and high temperature can reduce the stress resistance Kobresia pygmaea. Our findings suggest that the Kobresia pygmaea has high adaptability to climate warming in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to IPCC, the land surface air temperature increased by1.41 °C (1.31–1.51 °C) during 1880–2018 [1], and the temperature rises in high latitudes and high-altitude areas were even greater [2, 3]. Climate change has important effects on both morphological structure and physiological characteristics of plants [4]. In fact, climate warming in recent years has caused changes in vegetation phenology [5].The increasing temperature advances flowering time of plants, and a 2.5 °C increase in temperature of will cause the advance 5-25 days for flowering time of different species [6, 7]. Climate warming can also change the physiological metabolism of plant cells. High temperature can damage plant biomembrane structure, decrease cell water potential, increase relative permeability of lipid membrane and electrolyte extravasation. These changes can lead to physiological, biochemical and metabolic disorders in plants [8]. Although the responses of plant phenology, grassland community biomass, species composition and diversity to climate change have been extensively studied, there are few reports to the impact of climate change on plant physiology [9,10,11]. To cope with temperature stress, plants have evolved a variety of efficient mechanisms that allow them to adapt to the adverse conditions [12, 13]. This adaptive process involves a number of biochemical and physiological changes, including increased levels of proline, soluble sugars, and malondialdehyde, as well as enzyme activities [14]. These indices have been widely used to investigate the plant physiology response to high temperature and low temperature on plant seedlings, as well as plant leaves [15].

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP) is a unique eco-region because of its high elevation [16]. The QTP is mostly covered by land cover types of typical alpine meadow and steppe. These vegetation is not only providing important ecological functions such as carbon storage, water resource regulation, climate control at a global scale, but also providing critical ecosystem services such as pastoral production, cultural inheritance at local and regional scales [17, 18]. Therefore, it is important to understand the response mechanisms of vegetation to temperature change. Based on the remote sensing data, it was concluded that the vegetation cover showed an overall increasing trend since the 1980 s [19, 20], the QTP, a temperature-limited ecosystem, the vegetation growth is sensitive climate change [21]. It is reasonable to infer that the climate change not only affects vegetation coverage and biomass, and it may also have effects on the physiology of plant.

The grassland area of the QTP reaches 1.28 × 106 km2, accounting for about 50% of the total area. The alpine meadows and alpine grasslands account 49.3% and 44.9% of the total grassland area [22]. For the meadows, the Kobresia are the dominant species, and 56% of the alpine meadows are mainly consisted of these species. The Kobresia are the main forage grasses on the QTP [23]. The physiological effects of climate change on the leaves have been investigated using experimental warming [24]. It has been found that the leaf length and number of Kobresia pygmaea increased with temperature, but the content of malondialdehyde, free proline and antioxidant enzyme activity showed no significant changes [25]. Although the Kobresia pygmaea showed physiological response to climate change in the leaves, there are no comparative studies on the physiology of different organs of Kobresia pygmaea in different growing seasons. These knowledge gap hinder our understanding of effects of climate change on vegetation in alpine cold regions.

In this study, using laboratory experiments, Kobresia pygmaea samples which were collected in different growing seasons were cultivated at 23 °C, 10 °C, 4 °C and 0 °C in 2020. The content of malondialdehyde, free proline and soluble sugars in the leaves and roots were determined. We also measured the related antioxidant enzyme activities. The main goal of this study is to explore the physiological response of Kobresia pygmaea to temperature changes. Specifically, there are two scientific questions: 1) What are the seasonal physiological changes of Kobresia pygmaea leaves and roots under natural conditions? 2) Under different temperatures, what are the differences of physiological changes among different growing season of Kobresia pygmaea? Since the physiological ability to adapt to the environment can help plants to cope with environmental changes [26], the results will be helpful to understand the physiological adaptability of plants in alpine regions and their response to climate change in the future.

Results

Changes in malondialdehyde (MDA)

The content of malondialdehyde in leaves of Kobresia pygmaea fluctuated greatly among the different months. In June, the MDA content both in leaves and roots increased slightly with the decreasing incubation temperature. In July and August, the MDA contents in roots showed slightly decreased with the decreasing incubation temperature, while the changing trend of the leaves were opposite. In September, the mean MDA contents in roots and leaves also showed decreasing trends from 23 °C to 0 °C (Fig. 1).

Changes in osmotic regulation

The soluble sugar contents both in leaves and roots in June showed similar values in June. In July, the soluble sugar contents showed the lowest values at 0℃. In August, the soluble sugar content in the leaves and roots were relatively stable at different temperatures. In September, the soluble sugar contents in leaves varied considerably, while the contents in roots were lower at 0℃ in comparison with other temperatures (Fig. 2).

In June, the free proline contents in roots and leaves showed relatively stable changes at 23℃and 10℃. In July, the free proline contents in leaves and roots were higher at 10 °C and 4 °C. In August, the free proline contents were higher at 23 ℃, and the lowest values in roots were recorded at 0 ℃. For the samples collected in September, the free proline contents showed great variations, and the free proline contents in leaves and roots gradually increased with the decreasing temperature (Fig. 3).

Changes in enzyme activity

In June, the Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities in roots showed a greater fluctuation than those in leaves. In July and August, the SOD activities both in leaves and roots showed no significant changes at different temperatures. In September, the SOD activities in roots were largely lower at 4 °C and 0 °C than those at 23 °C and 10 °C, while the SOD activities contents in leaves increased slightly with the decreasing incubation temperature (Fig. 4).

The peroxidase (POD) activities in the roots in June were the lowest at 4 ℃ and 0 ℃. In July and August, the POD activities in leaves were significantly higher than those in roots. In September, the POD activities fluctuated considerably at all the four temperatures (Fig. 5). The Catalyse (CAT) activities in leaves were higher in June than other three months. From July to September, the CAT showed only slightly changes at different temperatures (Fig. 6).

Membership function of plant organs in different growing seasons at different temperatures

The membership function values were shown in Table 1. The greater membership function values, the higher osmotic adjustment substances accumulate, the higher the antioxidant enzyme activity, and the smaller the membrane damage in Kobresia pygmaea. According to the average values, the most harmful temperature to the leaves of plants is 23℃ in June and July. The most harmful temperature to the leaves is 10℃ in August and September (Table 1). In June and July, the most harmful temperature to the roots is 4℃. In August and September, the most harmful temperature to the roots is 0℃ (Table 2).

Multi-factor analysis of variance of physiological indices

Using multi-factor analysis of variance, the effects of organ, month, and temperature factors on physiological indices were analyzed (Table 3). Obviously, the organ has significant effects on all the indices (p<0.01), and the month has effects on most of the indices (p<0.01). The cultivate temperature has significant effects on Catalyze activity. The interaction of organ and cultivate temperature, month and cultivate temperature has significant effects on SOD and Catalyze activities.

Discussion

The MDA content is a reflection of lipid peroxidation and is usually used to measure stress-induced damage at the cellular level [27]. In this study, Kobresia pygmaea in different months showed responses to temperature changes. It suffered more damage in June with the decreasing incubation temperature than other months. The leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea in July and August are more able to adapt to temperature changes, and the content of MDA in leaves and roots were lower. Similar in September, decreasing MDA contents in leaves and roots with the decreasing incubation temperature. These results are similar to a previous report [28], indicating that with the decrease of stress temperature, the damage to plant cell membrane is intensified. Meanwhile, the growth stage can also affect the plant adaptivity to temperature changes. The self-repair ability of plant is higher during the July and August, and the MDA content shows a different degree of decline. Our results showed that the MDA content in the roots fluctuated considerably than that in leaves, indicating that the stress defense mechanisms in the roots started earlier and can effectively alleviate the damage to the cell membrane [29].

Osmotic adjustment is an important physiological mechanism for plants to resist low temperature adversity [30]. Soluble sugars plays an important role in the growth cycle of plants [31]. In this study, the soluble sugar content in the leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea in different months showed an increasing trend with the decreasing incubation temperature. It has been demonstrated that the protection of soluble sugars on plants is affected by stress temperature and time [32]. The increase of proline in plants is beneficial to improve the cold resistance of plants. Changes in proline content of plants are both affected by low temperature tolerance and the characteristics of germplasm resources [33]. In our study, with the decrease of the stress temperature, the proline content in the leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea in different months changed at different temperatures, indicating that the low temperature response in leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea was affected by temperature and, organs, and growing season, resulting in no consistency in the changes of proline content in plants [34]. It has been also suggested that the proline content of the three Cattleya varieties showed no significant differences among different stress temperatures [19]. Therefore, the changes in proline content in plants may be affected by multiple factors [35, 36].

SOD, POD and CAT as the enzymatic detoxification system of active oxygen can effectively remove the active oxygen free radicals in the plants [37]. Species, even varieties of the same species may have different cold resistance capabilities [38, 39]. In our study, the SOD activity in different organs of Kobresia pygmaea showed different changing trends with temperature among different months. The cold response of plants is a complex process, which can be regulated by a variety of enzymes and non-enzymatic systems [40]. In the process of scavenging active oxygen, SOD often cooperates with POD or CAT [41, 42]. In this study, the activity of SOD in leaves of Kobresia pygmaea in June under different temperature stresses were higher than that in other months, and the activities of POD and CAT were high and fluctuated greatly. This pattern may be related to the different changes in physiological indicators caused by the different mechanisms of different organs in response to low temperature [43]. Several studies suggested that the changing trends of protective enzyme activities in plants under low temperature stress are related to the genetic characteristics of the species, the living environment, the intensity of low temperature stress, tissues and organs and other factors [44].

The value of the membership function reflects the stress resistance of the plant. Using this index, previous reports suggested that the lowest tolerability in alfalfa appears at 0 °C [45]. Our results showed that the stress resistance of different organs of plants in different growing seasons were different. Higher temperatures damaged the leaves of plants, while lower temperatures damaged the roots of plants, indicating that different organs of plants have different tolerance to temperature, which may also be a temperature adaptation strategy of plateau plants. The growing seasons have a significant impact on the osmotic adjustment substances such as Pro and MAD and the activities of enzymes such as SOD and POD in plants. Our study also found that the interaction of organs, organs and months, as well as the interactions of organs, months, and stress temperature, have significant effects on physiological indicators. It has been shown that the stress resistance of plants was not only a complex quantitative trait affected by many factors, but also can be affected by growing seasons [46].

Conclusions

The growth temperature of plants in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is relatively low. In our study, we used laboratory experiments to examine the physiological response of Kobresia pygmaea to different temperatures. From high temperature(23 °C) to low temperature(0 °C), the osmotic adjustment substances in the leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea changed greatly in the June and September. SOD and POD activity in the leaves and roots of Kobresia pygmaea in different growing seasons fluctuated strongly, while CAT activities were higher in July and August. Although the physiological indicators in leaves and roots can positively reflect high temperature and low temperature, our results showed that higher temperatures were more harmful to plant leaves, and lower temperatures were more harmful to plant roots. Overall, the physiological indices of Kobresia pygmaea showed considerable variations to different temperatures. Due to the large temperature differences in our experiments, our findings suggested that the Kobresia pygmaea is a well adaptive specie to alpine environment, and the current climate warming may not lead significant changes in the growth of Kobresia pygmaea.

Methods

Study Area

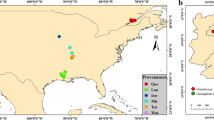

The study area, the Qilian Mountains are located between 98°75′~99°78′ E, 38°31′~38°82′ N (Fig. 7). The high variation in temperature and uneven distribution of monthly precipitation are the major features of the climate in this region [47]. Climatic data of the a local meteorological station showed that extreme high temperature ranges from 28.5 to 32.4℃ and extreme low temperature varies from −27.8 to −29.0℃. On average, the annual precipitation ranges from 401.9 to 632.3 mm, the annual evaporation varies between 1041.2 mm and 1234.2 mm, and the relative humidity is about 58% [48]. In our study area, the plant community diversity was investigated by sampling method. It was found that Kobresia pygmaea was the dominant specie, and others herbaceous plants were Carex atrata, Stipa capillata Linn, Elymus nutans Griseb and Oxytropis ochrocephala Bunge. These plants were common species on the QTP and were identified by Lisha Li. The sampling site ( 99°1′ E, 38°48′ N, 3700 m above sea level ) belongs to a Kobresia pygmaea meadow, and the coverage of Kobresia pygmaea during growth period on site is about 90% ( Fig. 1).

Experimental design and sample collection

Our study complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation, and no specific permits were required to collect the plant samples. The samples were collected monthly from June to September in 2020. According to the five-point sampling method, the 8 pieces of whole plant and soil was excavated about 10 cm×10 cm×10 cm in size with a small shovel at 3700 m above sea level. The samples were stored in 15 cm×10 cm×15 cm flowerpots and brought back to the laboratory for cultivation. The flowerpots were placed in a light incubator, and pre-adapted for 3 days at a temperature of 25 °C, light intensity of level 3 (240 µmol m−2 s−1), and light time of 16 h/8 h (day/night) [49]. After pretreatment, the samples were placed in a light incubator at 23 °C, and 2 g of Kobresia pygmaea leaves and roots were collected at 0 h, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 and 72 h. The samples were rinsed using deionization, dried using absorbent paper, wrapped in aluminum foil, and then stored in liquid nitrogen for laboratory analysis. After the sample collection, the light incubator was cooled at a rate of 2.5° C/h to 10 °C. The samples were also collected at these time intervals. Similarly, the leaves and roots samples of Kobresia pygmaea were collected under 4℃ and 0℃.

Physiological characteristics measurement

The content of malondialdehyde is determined using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) under acidic and high-temperature conditions, the maximum absorption peak appears at 532nm [50].

Proline content was determined spectrophotometrically using the ninhydrin method. The sample (0.5 g) was placed in a mortar, 5 ml of 3% sulfosalicylic acid was added and then the sample was grinded, homogenized and then transferred to a centrifuge tube, extracted in a boiling water bath for 10 min and cooled to room temperature. After centrifugation at 3000 r·min−1 for 10 min, the supernatant (2 ml) was mixed with 4 ml of acid ninhydrin reagent, 2 ml of glacial acetic acid and 2 ml of 3% sulfosalicylic acid, and the reaction mixture was placed in a boiling water bath for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature, 4 ml of toluene was added. After sufficient shaking, the red toluene was placed in a cuvette, and the absorbance was measured at 520 nm. The proline content of the sample was calculated according to the standard curve [51].

The soluble sugar content was determined by the anthrone method. The sample (0.1 g) was put into a 10 ml graduated centrifuge tube, added 4 ml of 80% ethanol, and boiled in water at 80℃ for 30 min with constant shaking. After a centrifugation at 3000 r·min−1 for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and placed in a 10 ml test tube. The residue was repeated the above process, and the supernatant was collected. By mixing 1 ml of supernatant and 5 ml of anthrone reagent, the mixture was water bathed in boiling water for 10 min. After cooling, the sample was performed colorimetry at 625 nm. The soluble sugar content was calculated according to the standard curve [52].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1) activity was measured by the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) method. The sample (0.1 g) was placed in a pre-cooled mortar, added 2 ml of extraction medium to grind, diluted to 10 ml, and centrifuged at 12,000 r·min−1 for 30 min. Combined 0.1 ml crude extract, 1.5 ml 50 mM PBS (pH 7.8), 0.3 ml 130 mM L-methionine, 0.3 ml 750 µM NBT, 0.3 ml 100 µM EDTA-Na2, 0.3 ml 20 µM riboflavin and 0.5 ml distilled water. The colorimetric tube was placed under a 4000 lx (light intensity) fluorescent lamp for 20 min, and the control tube was placed in a dark place, then the absorbance of each tube was measured at 560 nm. The SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that inhibited the rate of photoreduction of NBT by 50% and was expressed as U mg−1 protein [53].

The POD (EC 1.11.1.7) was determined by the guaiacol colorimetric method. The 3 ml reaction mixture (containing 50 ml 0.1 mol·L−1 PBS (pH 6.0), 19 µl of 30% H2O2 and 28 µg guaiacol) and 1ml crude enzyme solution was added to the colorimetric tube. The absorbance change of the reaction solution at 470 nm was measured every minute for a total of 4 min. The POD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to decompose 1 mol of H2O2 per min at 25˚C [54].

The activity of catalase (CAT, EC 1.11.1.6) was measured by UV absorption method. The sample (0.1 g) was mixed with 25 ml 0.2 mol·L−1 PBS (pH 7.8), and centrifuged at 4000 r·min−1 for 15 min to obtain a crude enzyme solution. 0.2 ml crude enzyme solution, 1.5 ml PBS (pH 7.8) and 1ml distilled water was mixed and preheated at 25℃, then 0.3ml 0.1 mol·L−1 H2O 2 was added, counted immediately after adding 1 tube, and quickly poured into quartz colorimetry tube, measured the absorbance at 240 nm. The CAT activity is defined as a decrease in absorbance of 0.1 per minute [55].

Statistical analysis

All the assays described above were repeated at least four times on five biological replicates. The membership function method was used to evaluate the adaptability of Kobresia pygmaea in different growing seasons to different temperatures. The indices of Kobresia pygmaea in response to low temperature stress were further analyzed by the method of multi-factor analysis of variance. We used SPSS 25, Statistic 10 for windows to complete the statistical analysis of the data, and used the Origin9.0 software for data mapping.

Membership function calculation formula: R(Xij) = (Xij -Xmin)/(Xmax -Xmin). R(Xij) is the subordinate function value of i variety j index; Xij is the resistance coefficient of a certain breed; Xmax and Xmin are the maximum and minimum values of the test varieties in the j index, respectively; The higher the membership function value R, the stronger the plant resistance.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

Change history

10 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03452-9

Abbreviations

- QTP:

-

Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

- SS:

-

Soluble sugar

- MDA:

-

malondialdehyde

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- POD:

-

peroxidase

- CAT:

-

catalase

References

IPCC: IPCC, 2019: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Cambridge University Press,Cambridge 2019.

Wang QX, Wang MB, Fan XH. Seasonal patterns of warming amplification of high-elevation stations across the globe. Int J Climat. 2018;38(8):3466–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5509.

Cao B, Zhang TJ, Peng XQ, Mu CC, Wang QF, Zheng L, Wang K, Zhong XY. Thermal characteristics and recent changes of permafrost in the upper reaches of the Heihe River Basin. Western China J Geophy Res Atmo. 2018;123(15):7935–49. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD028442.

Andrés P, Doblas-Miranda E, Mattana S, Molowny-Horas R, Vayreda J, Guardiola M, Pino J, Gordillo J. A battery of soil and plant indicators of NBS environmental performance in the context of global change. Sustain. 2021;13(4):1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041913.

Sarvia F, De Petris S, Borgogno-Mondino E. Exploring climate change effects on vegetation phenology by MOD13Q1 Data: the Piemonte region case study in the period 2001–2019. Agro. 2021;11(3):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11030555.

Sparks TH, Jeffree EP, Jeffree CE. An examination of the relationship between flowering times and temperature at the national scale using long-term phenological records from the UK. Int J Biometeorol. 2000;44(2):82–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004840000049.

Piao S, Tan J, Chen A, Fu YH, Ciais P, Qiang L, Janssens IA, Vicca S, Zeng Z, Jeong SJ. Leaf onset in the northern hemisphere triggered by daytime temperature. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6911. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7911.

Dat JF, Lopez-Delgado H, Foyer CH, Scott IM. Parallel changes in H2O2 and catalase during thermotolerance induced by salicylic acid or heat acclimation in Mustard seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(4):1351–7. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.116.4.1351.

Wischnewski J, Kramer A, Kong ZC, Mackay AW, Simpson GL, Mischke S, Herzschuh U: Terrestrial and aquatic responses to climate change and human impact on the southeastern T ibetan P lateau during the past two centuries. Global Change Biol 2011, 17 (11), 3376-3391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02474.x.

Piao S, Mohammat A, Fang J, Qiang C, Feng J: NDVI-based increase in growth of temperate grasslands and its responses to climate changes in China. Global Environ Change 2006, 16 (4), 340-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.002.

Lesica P, Kittelson PM. Precipitation and temperature are associated with advanced flowering phenology in a semi-arid grassland. J Arid Environ. 2010;74(9):1013–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.02.002.

Wright IJ, Reich PB, Cornelissen J, Falster DS, Groom PK, Hikosaka K, Lee W, Lusk CH. Niinemets ü, Oleksyn J: Modulation of leaf economic traits and trait relationships by climate. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;15(5):411–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-822x.2005.00172.x.

Bohnert HJ, Jensen N: Adaptations to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 1995, 7 (7), 1099. https://doi.org/10.2307/3870060.

Halliwell., Barry: Reactive species and antioxidants. redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol 2006, 141 (2), 312-322. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.077073.

Huang B, Dacosta M, Jiang Y. Research advances in mechanisms of turfgrass tolerance to abiotic stresses: from physiology to molecular biology. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2014;33(2–3):141–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2014.870411.

Dong S, Sherman R. Enhancing the resilience of coupled human and natural systems of alpine rangelands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Rangeland J. 2015;37(1):i. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ14117.

Wesche K, Ambarl D, Kamp J, Trk P, Treiber J, Dengler J. The Palaearctic steppe biome: a new synthesis. Biodiversi Conserv. 2016;25(12):2197–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1214-7.

Dong S, Shang ZH, Gao JX, Boone RB. Enhancing sustainability of grassland ecosystems through ecological restoration and grazing management in an era of climate change on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agr Ecosys tEnviron. 2020;287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106684

Wang Q, Yu XN: Physiological response to low temperature stress and evaluation of cold resistance of three herbaceous peony cultivars. J Anhui Agri Sci 2015, 35 (5), 104-109. https://doi.org/10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2015.25.146.

Jiao K, Gao J, Liu Z. Precipitation drives the NDVI distribution on the Tibetan Plateau while high warming rates may intensify its ecological droughts. Remote Sens. 2021;13(7):1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13071305.

Piao S, Cui M, Chen A, Wang X, Ciais P, Liu J, Tang Y: Altitude and temperature dependence of change in the spring vegetation green-up date from 1982 to 2006 in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Agr Forest Meteorol 2011, 151 (12), 1599-1608.

Liu QJ, Kondoh A, Takeuchi N: Study of changes in life zone distribution in north-east China by climate–vegetation classification. Ecol Res 2010, 13 (3), 355-365. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1703.1998.00275.x

Yang Y, Wang GX, Yang LD, Guo JY, Li N. Physiological responses of Kobresia pygmaea to warming in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau permafrost region. Acta Ecol. 2012;39:109–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2012.01.012.

Yan Y, Wang G, Klanderud K, Yang L: Responses in leaf functional traits and resource allocation of a dominant alpine sedge (Kobresia pygmaea) to climate warming in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau permafrost region. Plant Soil 2011, 349 (1), 377-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0891-y

Peng AH, Wang G, Yang Y, Yao X, Li Z, Yang Y: Effects of experimental warming on the growth and stoichiometrical characteristics of two dominant species(Kobresia pygmaea and Kobresia tibetica) in alpine meadow of the Tibetan Plateau. Acta Ecol Sinica 2017, 37 (12), 4118-4127. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201606161173

Gratani L, Catoni R, Pirone G, Frattaroli AR, Varone L. Physiological and morphological leaf trait variations in two Apennine plant species in response to different altitudes. Photosynthetica. 2012;50(1):15–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-012-0006-x.

Bao G, Tang W, An Q, Liu Y, Zhu S. Physiological effects of the combined stresses of freezing-thawing, acid precipitation and deicing salt on alfalfa seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02413-4.

Wang F, Zhao X, Liang DY, Pei XN, Zhang QH, Zhang P, Zhang JQ, Lu ZM, Yang YC, Liu GF: Study on the physiological indices of Pinus sibirica and Pinus koraiensis seedlings under cold stress. J Forestry Res 2019, 30 (4), 1255-1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-018-0833-0

Posmyk MM, Bailly C, Szafrańska K, Janas KM, Corbineau F: Antioxidant enzymes and isoflavonoids in chilled soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) seedlings. J Plant Physiol 2005, 162 (4), 403-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2004.08.004.

Fry JD, Lang NS, Clifton R, Maier FP: Freezing tolerance and carbohydrate content of low-temperature-acclimated and nonacclimated centipedegrass. Crop Sci 1993, 33 (5), 1051-1055. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1993.0011183X003300050035x.

Muhi E, Hussien I, Zhu X, Zhou G, Farah GA. Nitrogen fertilizer alleviated negative impacts of nacl on some physiological parameters of wheat. Pak J Bot. 2018;50(6):2097–104.

Wormit A, Trentmann O, Feifar I, Lohr C, Tjaden J, Meyer S, Schmidt U, Neuhaus E. Molecular identification and physiological characterization of a novel monosaccharide transporter from arabidopsis involved in vacuolar sugar transport. Plant Cell. 2006;18(12):3476–90. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.047290.

Parvanova D, Popova A, Zaharieva I, Lambrev P, Konstantinova T, Taneva S, Atanassov A, Goltsev V, Djilianov D. Low temperature tolerance of tobacco plants transformed to accumulate proline, fructans, or glycine betaine. Variable chlorophyll fluorescence evidence Photosynthetica. 2004;42(2):179–85. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHOT.0000040588.31318.0f.

Molinari HBC, Marur CJ, Bespalhok Filho JC, Kobayashi AK, Pileggi M, Júnior RPL, Pereira LFP, Vieira LGE: Osmotic adjustment in transgenic citrus rootstock Carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis Osb. x Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) overproducing proline. Plant Sci 2004, 167 (6), 1375-1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.007.

He H, Lei Y, Yi Z, Raza A, Zeng L, Yan L, Yong C: Study on the mechanism of exogenous serotonin improving cold tolerance of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. Plant Growth Regul 2021, 94 (2), 161-170.

Delauney AJ, Verma DPS. Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J Cell Mole Biol. 1993;4(2):215–23. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04020215.x.

Guo Z, Ou W, Lu S, Zhong Q. Differential responses of antioxidative system to chilling and drought in four rice cultivars differing in sensitivity. PlantPhysiol Bioch. 2006;44(11–12):828–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.10.024.

Tajvar Y, Ghazvini RF, Hamidoghli Y, Sajedi RH. Antioxidant changes of Thomson navel orange (Citrus sinensis) on three rootstocks under low temperature stress. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2011;52(6):576–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13580-011-0052-5.

Santini J, Giannettini J, Pailly O: Comparison of photosynthesis and antioxidant performance of several citrus and fortunella species (rutaceae) under natural chilling stress. Trees 2013, 27 (1), 71-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-012-0769-5.

Levitt J: Responses of plants to environmental stress, volume 1: Chilling, freezing, and high temperature stresses.: Academic Press.; 1980.

Yadav SK. Cold stress tolerance mechanisms in plants. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2010;30(3):515–27. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009050.

Tan K, Zhang B, Zhang HK, Ma HY, Li SK, Zheng HP. Enzymes and non-enzymatic antioxidants responses to sequential cold stress in polymorphic noble scallop Chlamys nobilis with different total carotenoids content. Fish Shell Fish Immun. 2020;97:617–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2019.12.063.

Beer RF, Seizer TW. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952;195(1):133–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60016-9.

Holmberg N, Bülow L. Improving stress tolerance in plants by gene transfer. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3(2):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01163-1.

Wang RY, Ren YS, Yue WB, Dong KH, Yang GY: Effect of low temperature stress on the survival and physiological and biochemical indexes of Alfalfa seedlings. Acta Laser Biol Sinica 2006, 15 (4): 342. https://doi.org/1007-714604-0342-07.

Cao ZH, Wu ZN, Cai RS, Liu JL, Gao J: Comprehensive evaluation on the growth and physiological indexes of cold resistance of different phllostachys edulis provenance in AnHui province. J Bamboo Res 2018, 37 (03),45-50. https://doi.org/10.19560/j.cnki.issn1000-6567.2018.03.008.

Gou X, Zhang F, Deng Y, Ettl G, J., Yang M, X., Gao L, L., Fang K, Y.: Patterns and dynamics of tree-line response to climate change in the eastern Qilian Mountains, northwestern China. Dendrochronologia 2012, 30 (2), 121-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2011.05.002.

Liu XH, Qin DH, Shao XM, Chen T, Ren J. Temperature variations recovered from tree-rings in the middle Qilian Mountain over the last millennium. Sci China, Ser D: Earth Sci. 2005;48(4):521–9. https://doi.org/10.1360/03yd0063.

Hu ZR, Fan JB, Chen K, Amombo E, Chen L, Fu J. Effects of ethylene on photosystem II and antioxidant enzyme activity in Bermuda grass under low temperature. Photosynth Res. 2016;128(1):59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-015-0199-5.

Heath RL, Packer L: Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys 1968, 125 (1), 189-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1.

Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39(1):205–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060.

Dreywood R. Qualitative test for carbohydrate material. Ind Eng Chem Anal Ed. 1946;18(8):499–499. https://doi.org/10.1021/i560156a015.

Giannopolites CN, Ries SK. Superoxide dismutase occurrence in higher plants. Plantphysiol. 1977;59(2):309–14. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.59.2.309.

Zaharieva T, Yamashita K, Matsumoto H. Iron deficiency induced changes in ascorbate content and enzyme activities related to ascorbate metabolism in cucumber roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999;40(3):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029538.

Maehly AC: The assay of catalases and peroxidases.: Methods of Biochemical Analysis: Volume 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470110171.ch14.; 1954.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41861011), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA20100103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41661013), the state key laboratory of Cryospheric Science (SKLCSZZ-2021), and the West Light Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HX designed the study; LL, NM, ZG, XL, BZ performed the field study and measured the physiological parameters, GL analyzed the data. XW supervised and conceived the study. All the authors wrote the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: it was noted that due to a typesetting error, authors, Haiyan Xu and Lisha Li were not tagged as equal contributors.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, H., Li, L., Mao, N. et al. Physiological response of Kobresia pygmaea to temperature changes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. BMC Plant Biol 22, 51 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03428-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03428-9