Abstract

The effects of cropping practices on the rhizosphere soil physical properties and microbial communities of Bupleurum chinense have not been studied in detail. The chemical properties and the microbiome of rhizosphere soil of B. chinense were assessed in the field trial with three cropping practices (continuous monocropping, Bupleurum-corn intercropping and Bupleurum-corn rotation). The results showed cropping practices changed the chemical properties of the rhizosphere soil and composition, structure and diversity of the rhizosphere microbial communities. Continuous monocropping of B. chinense not only decreased soil pH and the contents of NO3−-N and available K, but also decreased the alpha diversity of bacteria and beneficial microorganisms. However, Bupleurum-corn rotation improved soil chemical properties and reduced the abundance of harmful microorganisms. Soil chemical properties, especially the contents of NH4+-N, soil organic matter (SOM) and available K, were the key factors affecting the structure and composition of microbial communities in the rhizosphere soil. These findings could provide a new basis for overcoming problems associated with continuous cropping and promote development of B. chinense planting industry by improving soil microbial communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bupleurum chinense (Apiaceae) is an important medicinal plant that has been used in China and other Asian countries for thousands of years. The plant has many important properties, such as anti-inflammatory [1], liver-protecting [2], anti-depressant [3], anti-tumor [4], and immunomodulatory [5] activities, and is widely used in the clinical treatment of fever, influenza, malaria, distending pain in the chest, menstrual disorders, and other symptoms. The active components of Bupleuri radix mainly include saponins [6], polysaccharides [7], essential oil [8], flavones [9], and coumarin [10]. These compounds are not only related to Bupleurum germplasm, but are also influenced by the production environment and cropping practices [9, 11].

In the recent decades, as a result of rapid development and large-scale cultivation, the planting area of B. chinense has expanded substantially. However, due to the limited available land and maximum economic benefits, the continuous cultivation of B. chinense is becoming increasingly popular. Studies showed that long-term continuous cropping resulted in decreased abundance of beneficial microorganisms in soil, the increase in pathogenic microorganisms, and the decrease in yield and quality of medicinal materials [12]. For example, the continuous planting of American ginseng [13] and Sophora flavescens [14] not only decreased weakened soil microbial diversity and amassed fungal root pathogens, but also changed soil physical properties, resulting in decreased crop yield and quality.

Studies have shown that multiple cropping system [characterized by more than one crop grown together, either mixed in space (intercropping) or time (crop rotation)] can effectively alleviate the problems associated with monocropping. Intercropping, in which two or more crops are planted in the same field, can increase the absorption of trace elements, improve soil fertility [15] and reduce the risk of pests and diseases [16]. For example, the intercropping of turmeric, ginger and patchouli not only changed the soil physical properties and the microbial community structure, but also improved the quality of patchouli [17].

Crop rotation involves the systematic rotation of different types of crops in the same field. Crop rotation can balance soil nutrients, improve soil chemical properties, increase the abundance of beneficial microorganisms, and enhance disease resistance [18]. For example, the rotation Pinellia ternata-wheat improved soil microecological environment, enriched beneficial microorganisms and diminished pathogenic microorganisms [19].

However, the effects of cropping practices on the rhizosphere soil microecology of B. chinense have not been studied in detail, especially the dynamic changes in rhizosphere soil microorganisms and soil physical and chemical properties after continuous planting of B. chinense. This lack of knowledge affects the development of B. chinense planting industry.

The objective of the study was to investigate the effect of cropping practices on soil rhizosphere microecology of B. chinense. A high-throughput Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform was used to determine the microbial community structures in the B. chinense rhizosphere soil in different cropping practices. The chemical properties of rhizosphere soil were determined by the previously reported methods [20]. Our study could provide a new basis for overcoming continuous-cropping obstacles and promote development of B. chinense planting industry.

Materials and methods

Field experiment

The experimental site was a trial plot of Shandong University of Chinese Medicine, Shandong Province, China (117°22′54″ E 36°35′27″ N, altitude 524 m). The annual average sunshine was 2647.6 h, and the sunshine rate was 60%. The annual average temperature was 12.8 °C, and the annual average precipitation was 600.8 mm. The soil type was brown soil.

The field experiment was conducted from June 2016 to October 2020. The field trial area was divided into three plots of 5 × 5 square meters each. Three treatments were implemented: B. chinense continuous cultivation (BCC), B. chinense intercropped with corn (BIC) and growing corn after B. chinense (BCR); each treatment had three repetitions. Cultivation time and sowing of Bupleurum seeds and corn are shown in Table 1. All the experimental plots were subjected to the same field management practices, including manual weeding, no fertilizer and no watering. During the experiment, the soil microbial and chemical characteristics were analyzed for three consecutive years to assess temporal variation. After the flowering of B. chinense in September of the second year, soil samples of the three cropping treatments were taken for comparative analysis.

Collection of soil samples

Rhizosphere soil samples were collected in October 2020. Rhizosphere soil samples from 30 plant were collected from five different sites using the Z-type method in each experimental plot. Then, 30 rhizosphere samples were combined into a composite sample [21]. There were triplicate rhizosphere soil samples for each treatment. Firstly, the loose soil was shaken off from roots (the depth of roots was about 10 cm), and the soil closely adhering to the root system was sampled as rhizosphere soil by brushing it off [22]. The collected soil was then placed in a sealed sterile bag and taken back to the laboratory. Each soil sample was divided into two subsamples: one for chemical analysis, and the other was stored at − 20 °C for microbial analysis.

Chemical properties

After air-drying, the pH value of the soil was measured using a pH meter (pHS-3S) (2.5:1 water:soil ratio), and the contents of soil organic matter (SOM) (SOM = SOC × 1.724), available phosphorus (Ava-P), and available potassium (Ava-K) were determined by the methods reported by Qu et al. [23]. Determination of NO3−-N and NH4+-N in soil was done by UV spectrometry as reported by Xing et al. [24].

DNA extraction

A PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to extract DNA from soil samples. Each soil sample was extracted according to the PowerSoil kit manufacture’s protocol. The extracted DNA was eluted using 100 μL sterile water, quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Canada) and stored at − 20 °C for further use.

PCR amplification and Illumina MiSeq sequencing

The V4-V5 region of bacterial 16S rDNA was amplified using the primers 515F 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′ and 926R 5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTGAGTTT-3′, whereas the fungal ITS1 region was amplified using F 5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′, and R 5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). The primers also contained the Illumina 5′-overhang adapter sequences for two-step amplicon library building, following manufacturer’s instructions. The initial PCR reactions were carried out in 50 μL reaction volumes with 1–2 μL DNA template, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.2 μM of each primer, 5 × reaction buffer 10 μL, and 1 U Phusion DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, USA). PCR conditions consisted of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min [21]. The barcoded PCR products were purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen, USA) and quantified using an FTC − 3000 TM real-time PCR (Funglyn Shanghai). The PCR products from different samples were mixed at equal ratios. The second step PCR with dual 8 bp barcodes was used for multiplexing. Eight-cycle PCR reactions were used to incorporate two unique barcodes to either end of the amplicons. Cycling conditions consisted of 1 cycle at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 8 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. The library was purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen, USA) and sequenced by 2 × 250 bp paired-end sequencing on a Novaseq platform using a Novaseq 6000 SP 500 Cycle Reagent Kit (Illumina USA) at TinyGen Bio-Tech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Illumina data analysis

The raw fastq files were demultiplexed based on the barcode. The PE reads for all samples were run through Trimmomatic (version 0.35) to remove low quality base pairs using the parameters SLIDINGWINDOW 50:20 and MINLEN 50. The trimmed reads were then cut to separate adaptors using Cutadapt (version 1.16) and were merged using FLASH program (version 1.2.11) with default parameters.

The sequences were analyzed using a combination of software Mothur (version 1.33.3), UPARSE (usearch version v8.1.1756, http://drive5.com/uparse/), and R (version 3.6.3). The demultiplexed reads were clustered at 97% sequence identity into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The singleton OTUs were deleted using the UPARSE pipeline (http://drive5.com/usearch/manual/uparse cmds.html). The representative OTU sequences of bacteria were assigned taxonomically against the Silva 128 database (ITS in Unite database) with confidence score ≥ 0.6 by the classify.seqs command in Mothur.

The indices of alpha diversity were calculated by Mothur. For the beta diversity analysis, the Weighted UniFrac distance algorithm was used to calculate the distance between samples. In LEfSe analysis, the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score was computed for taxa differentially abundant between the two treatments. A taxon at P < 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis test) and log10[LDA] ≥ 2.0 (or ≤ − 2.0) was considered significant. Statistical and visual analysis of dilution curves, community structure histogram, NMDS and RDA were performed using R language (Version 3.6.3). PICRUSt software and FUNGuild software were used to predict the function of bacterial and fungal gene sequences, respectively.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 21.0. The data on the chemical properties and microbial diversity of rhizosphere soil were analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Differences in the relative abundances of microbial taxa among treatments were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the 0.05 probability level.

Results

The effect of cropping practices on the rhizosphere soil chemical properties

The chemical properties of B. chinense rhizosphere soil in different treatments are shown in Table 2. Compared with intercropping and crop rotation, soil pH and the contents of NO3−-N and Ava-K decreased after continuous planting of B. chinense, but the Ava-P content increased. The chemical parameters of rhizosphere soil differed significantly among the treatments, except for the NO3−-N content.

Amplicon sequencing and rarefaction curves

To characterize the microbiome in the B. chinense rhizosphere soil in different cropping practices, nine samples were sequenced by Illumina MiSeq. The amplicon sequencing resulted in 450,038 effective reads of bacterial 16S rRNA genes and 437,141 effective reads of fungal ITS region. Based on 97% similarity, the OTUs of microbial community in the rhizosphere soil were obtained. The results are shown in supplementary Table 1.

To construct rarefaction curves, the dataset was flattened according to the minimum number of sample sequences. The rarefaction curves of nine rhizosphere soil samples were constructed based on the number of OTUs observed (Supplementary Fig. 1). The rarefaction curves showed that the number of OTUs rose sharply and then gradually flattened out, indicating that the sequencing library reached saturation. Therefore, it could be used for analyzing the diversity of microorganisms in the rhizosphere soil of B. chinense.

Alpha diversity of bacterial and fungal communities

The alpha diversity represents the measurement of within-community microbial diversity (Table 3). Theoretically, the larger the Shannon index or the smaller the Simpson index, the higher the community diversity. According to the Shannon index, the bacterial richness was highest (6.513) in the rhizosphere soil of the rotation of B. chinense and corn, followed by continuous monocropping (6.421) and intercropping of B. chinense and corn (6.328). The Simpson index analysis confirmed the above-mentioned diversity analysis. Shannon index and Simpson index values for fungal communities in the rhizosphere of B. chinense-corn intercropping were 4.401 and 0.029, respectively, followed by those of rotation with corn (4.250 and 0.033, respectively), and the lowest diversity values were in B. chinense monocropping (4.201 and 0.049, respectively). The results showed that the rotation and intercropping of B. chinense with corn were the main factors affecting the diversity of, respectively, bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere. In summary, the cropping practices had an important effect on the diversity of rhizosphere microorganisms.

Beta diversity of bacterial and fungal communities

In order to shed more light on the differences in microbial community structure, NMDS analysis was performed based on the Weighted UniFrac distance (Fig. 1), and the samples could be divided into three groups, according to the species composition in the B. chinense rhizosphere. There were similarities in the structure of microbial communities within the treatments and significant differences in the structure among the treatments, which indicated that the cropping practices in the same field strongly influenced the composition of microbial communities in the B. chinense rhizosphere.

The composition and structure of the bacterial community

In order to clarify the microbial community structure in the B. chinense rhizosphere, two taxonomic levels (phylum and genus) were analyzed.

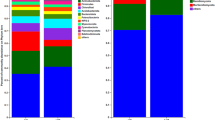

As shown in Fig. 2A, 13 bacterial phyla were detected in the soil from different cropping practices. The dominant bacterial phyla in the B. chinense rhizosphere soil were Proteobacteria, followed by Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Chloroflexi. As compared to BIC and BCC, continuous cropping of B. chinense for 3 years resulted in higher abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, but in lower abundance of Acidobacteria.

At the genus level (Fig. 3A), 79 bacterial genera were detected in the rhizosphere soil from different cropping practices. The dominant genera were Pseudarthrobacter, Microvirga, Gaiella, Nitrospira, and Pirellula. Compared with the intercropping and rotation of B. chinense and corn, the relative abundance of Pseudarthrobacter and Gaiella increased after continuous cropping. However, the relative abundance of Microvirga and Nitrospira showed a downward trend after continuous cropping and intercropping (Fig. 4A).

Relative abundances of the top 20 bacterial and fungal genera in the rhizosphere of Bupleurum chinense in different cropping practices. Vertical bars represent the mean standard deviation of three replicates. Asterisks with different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) based on LSD. A Bacteria, B Fungi

The composition and structure of the fungal community

As shown in Fig. 2B, five fungal phyla were detected in the soil from different cropping practices. The dominant fungal phyla were Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota. The relative abundance of Ascomycota decreased after continuous cropping and intercropping, but increased after rotation with corn. The relative abundance of Basidiomycetes increased after continuous cropping, but decreased after intercropping and rotation.

At the genus level (Fig. 3B), 60 fungal genera were detected in the soil from different cropping practices. The dominant fungal genera in the rhizosphere soil were Gibberella, Cercophora, Fusarium, Chaetomium, Mortierella, Preussia, Cryptococcus, Alternaria, unclassified_Ascobolaceae, Cladorhinum, Paraphoma, Knufia, and Cladosporium. After 3 years of continuous cultivation of B. chinense, the relative abundance of Cercophora, Cryptococcus, Alternaria, Paraphoma and Cladosporium increased, but the relative abundance of Chaetomium, Mortierella, Preussia and Cladorrhinum significantly decreased (Fig. 4B).

Correlation analysis of dominant microorganisms and soil properties

Soil chemical properties were important explanatory factors that determined the clustering patterns of soil microbial communities in different cropping treatments [25]. The chemical properties of the B. chinense rhizosphere soil were significantly different under different cropping practices (Table 2). Therefore, redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted on the relative abundance of dominant bacterial and fungal genera and soil chemical factors (Fig. 5). The results showed that the cumulative variation explained by the soil chemical properties was 87.84 and 59.31% for bacteria and fungi, respectively, indicating that explanatory variables had a significant influence on the structure of microbial communities. The effects of soil chemical properties on bacteria and fungi were in the order of NH4+-N > SOM > Ava-K > pH > NO3−-N > Ava-P and NH4+-N > SOM > Ava-K > Ava-P > pH > NO3−-N, respectively (Fig. 5). In conclusion, NH4+-N, SOM and Ava-K were the main chemical properties that affected the microbial abundance and composition in the Bupleurum rhizosphere soil.

Biomarker analysis

In order to identify the dominant microbial biomarkers in the B. chinense rhizosphere soil under different cropping practices, the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was carried out (Fig. 6). The LDA results identified 30, 33 and 55 bacterial biomarkers in continuous monocropping, intercropping and rotation with corn, respectively (Fig. 6A). The most abundant bacterial family was Comamonadaceae from B. chinense continuous monocropping soil. Rhizobium giardinii, Desulfurellaceae and Burkholderiales were abundant in the rhizosphere of B. chinense intercropped with corn, whereas Methylobacteriaceae and Microvirga were significantly enriched in the rhizosphere of B. chinense in rotation with corn.

For the fungal community, we identified 92, 57 and 34 fungal biomarkers in continuous monocropping, intercropping and rotation with corn, respectively (Fig. 6B). The relatively abundant biomarker fungal taxa included Dothideomycetes and Pleosporales in the B. chinense continuous monocropping, Chaetomiaceae, Mortierellaceae and Zygomycota in B. chinense intercropped with corn, and Nectriaceae, Chytridiomycetes and Rhizophlyctidales in B. chinense in rotation with corn.

Functional analysis

In order to explore the functional changes in soil bacteria in different cropping treatments, six categories of biological metabolic pathways (main functional levels) were identified by comparing with KEGG database. It included metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, human diseases, and organismal systems, accounting for 66, 11, 8, 7, 5, and 3%, respectively. In addition, 24 sub-functions such as amino acid metabolism, energy metabolism, metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, and translation were found by analyzing the secondary functional layers of predictive genes (Fig. 7A).

The secondary pathways of B. chinense under different cropping treatments were similar, that is, carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism were significantly higher than the other metabolic pathways. The carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism were higher in continuous cropping of B. chinense than in other cropping patterns.

According to the FUNGuild database, at least eight nutrient patterns were detected in this study, whereby saprophytes were most abundant, followed by pathotroph-saprotroph-symbiotroph and pathotroph-saprotroph patterns. The relative abundance of fungal functions varied significantly among different treatments. Compared with intercropping and rotation, pathotrophs, pathotroph-symbiotrophs, and pathotroph-saprotrophs were most abundant in continuous cropping (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

Soil chemical characteristics are the important indices for evaluating soil quality. Cropping practices influenced not only the chemical properties of soil, but also governed the composition of rhizosphere microorganisms [26]. Therefore, elucidating the changes in soil chemical properties can provide a basis for characterizing soil productivity under different cropping practices. A decrease in soil nutrients was associated with a decrease in diversity of rhizosphere microbial community, which is one of the main causes of problems with crop continuous cropping. However, intercropping and rotation increased soil nutrient contents, thereby increasing the diversity of rhizosphere microbial community and alleviating continuous cropping problems [27].

In our study, the contents of pH, NO3−-N and Ava-K decreased after continuous cropping of B. chinense, but increased after intercropping and rotation with corn. Studies have shown that continuous monocropping systems have a negative impact on soil function and sustainability [28, 29]. Soil nutrient contents such as SOM, Ava-P, Ava-K, NO3−-N and NH4+-N showed a decreasing trend after continuous cropping. However, rotation or intercropping with corn effectively alleviated this decline and imbalance in soil nutrients caused by continuous monocropping [26, 30]. Our experiment, confirming the above findings, contributed to the sustainable development of B. chinense planting industry through rotation of B. chinense with corn. Studies have shown that soil organic matter is a key factor affecting soil microbial community diversity, and high soil organic matter content is conducive to improving soil bacterial community diversity [31]. In our study, the rhizosphere soil bacterial diversity increased after B. chinense rotation, but decreased after B. chinense intercropping with corn, which might have been related to the decrease in organic matter content after B. chinense intercropping and the increase of organic matter after rotation.

Higher soil microbial community diversity is indicative of higher soil health and plant productivity [32]. Soil microbial diversity not only has an important impact on soil quality, function and sustainability [33], but also is a key factor in the control of pathogenic microorganisms [34]. Therefore, the loss of soil microbial diversity and function is one of the reasons for poor crop growth under continuous monocropping. In order to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the test results, the soil microbial and chemical properties were analyzed for three consecutive times during the experiment. Our results showed the cropping practice of B. chinense significantly affected the structure and composition of soil microbial community. In B. chinense continuous monocropping, alpha diversity decreased, but this change could be alleviated by rotation or intercropping with corn. Similar results were also obtained in continuous monocropping of sugar beet [22] and Coptis chinensis Franch [35]., intercropping of potato with onion and tomato [36] and intercropping of black pepper and vanilla [30], as well as rotation of Brassica vegetables with eggplant [26], and Pinellia ternata with wheat [19].

Beta diversity showed that cropping practices had a strong influence on the soil microbial community. In other words, the use of different cropping systems may lead to significant differences in the structure of microbial communities in soil [37]. Importantly, changes in microbial community structure and composition usually are associated with changes in plant metabolic capacity, biodegradation, disease inhibition, and other functions [38].

In our study, the continuous monocropping of B. chinense strongly reduced the abundance of beneficial microorganisms, such as Microvirga, Haliangium, Chaetomium, Mortierella, Preussia, and Cladorrhinum. These rhizosphere microorganisms played an important role in plant growth and the inhibition of pathogenic microorganisms [39,40,41,42,43]. By contrast, some potentially pathogenic microorganisms, such as Cercophora [44], Alternaria, Paraphoma, Cladosporium [45], Monographella [46], Hydropisphaera [47], and Colletotrichum were significantly amplified. For example, Alternaria and Paraphoma can cause root rot of B. chinense [25, 48], and Colletotrichum can infect leaves to produce disease spots [49]. In this study, ecological functions in the rhizosphere soil of B. chinense in different cultivation modes were predicted. Among fungi, compared with other groups, the abundance of pathotrophs, pathotroph-symbiotrophs, and pathotroph-saprotrophs, which may cause plant diseases, increased significantly in continuous cropping.

Conclusion

The results showed that continuous cropping of B. chinense resulted in the decrease of pH, NO3−-N and Ava-K in the rhizosphere soil, and the decrease in rhizosphere bacterial and fungal α-diversity. The relative abundance of beneficial microorganisms was reduced, and intercropping and rotation could alleviate these problems. Soil chemical properties, especially the contents of NH4+-N, SOM and Ava-K, influenced the microbial structure and composition of the B. chinense rhizosphere soil. These findings could provide a new basis for overcoming the problems associated with continuous cropping and promoting development of B. chinense planting industry by improving soil microbial communities.

Availability of data and materials

All sequencing data were deposited into NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the Bioproject number PRJNA777373.

References

Jia R, Gu Z, He Q, Du J, Cao L, Jeney G, et al. Anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects of radix bupleuri extract against oxidative damage in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) via Nrf2 and TLRs signaling pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;93:395–405.

Wang YX, Du Y, Liu XF, et al., et al. A hepatoprotection study of radix bupleuri on acetaminophen-induced liver injury based on CYP450 inhibition. Chin. J Nat Med. 2019;17:517–24.

Feng HC, Wang CM, Tang MZ, Wu XJ, Zhou ZC, Wei MD, et al. Antidepressant effect of total saponins of radix bupleuri and the underlying mechanism on a mouse model of depression. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34:1097–103.

Song X, Ren T, Zheng Z, Lu T, Wang Z, Du F, et al. Anti-tumor and immunomodulatory activities induced by an alkali-extracted polysaccharide BCAP-1 from Bupleurum chinense via NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;95:357–62.

Cheng XQ, Li H, Yue XL, Xie JY, Zhang YY, Di HY, et al. Macrophage immunomodulatory activity of the polysaccharides from the roots of Bupleurum smithii var. parvifolium. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:363–8.

Yuan B, Yang R, Ma Y, Zhou S, Zhang X, Liu Y. A systematic review of the active saikosaponins and extracts isolated from radix bupleuri and their applications. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:620–35.

Feng Y, Weng H, Ling L, Zeng T, Zhang Y, Chen D, et al. Modulating the gut microbiota and inflammation is involved in the effect of Bupleurum polysaccharides against diabetic nephropathy in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;132:1001–11.

Li X, Jia Y, Song A, Chen X, Bi K. Analysis of the essential oil from radix bupleuri using capillary gas chromatography. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2005;125:815–9.

Yang LL, Yang L, Yang X, Zhang T, Lan YM, Zhao Y, et al. Drought stress induces biosynthesis of flavonoids in leaves and saikosaponins in roots of Bupleurum chinense DC. Phytochemistry. 2020;177:112434.

Jiang H, Yang L, Hou A, Zhang J, Wang S, Man W, et al. Botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, analytical methods, processing, pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of bupleuri radix: a systematic review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110679.

Yang L, Zhao Y, Zhang Q, Cheng L, Han M, Ren Y, et al. Effects of drought-re-watering-drought on the photosynthesis physiology and secondary metabolite production of Bupleurum chinense DC. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:1181–97.

Tong AZ, Liu W, Liu Q, Xia GQ, Zhu JY. Diversity and composition of the Panax ginseng rhizosphere microbiome in various cultivation modes and ages. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:18.

Zhang J, Fan S, Qin J, Dai J, Zhao F, Gao L, et al. Changes in the microbiome in the soil of an American ginseng continuous plantation. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:572199.

Lei H, Liu A, Hou Q, Zhao Q, Guo J, Wang Z. Diversity patterns of soil microbial communities in the Sophora flavescens rhizosphere in response to continuous monocropping. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1427–41.

Wang ZG, Jin X, Bao XG, Li XF, Zhao JH, Sun JH, et al. Intercropping enhances productivity and maintains the most soil fertility properties relative to sole cropping. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113984.

Fernández-Aparicio M, Amri M, Kharrat M, Rubiales D. Intercropping reduces Mycosphaerella pinodes severity and delays upward progress on the pea plant. Crop Prot. 2020;297:744–50.

Zeng J, Liu J, Lu C, Ou X, Luo K, Li C, et al. Intercropping with turmeric or ginger reduce the continuous cropping obstacles that affect Pogostemon cablin (patchouli). Front Microbiol. 2020;11:579719.

Peralta AL, Sun YM, McDaniel MD, Lennon JT. Crop rotational diversity increases disease suppressive capacity of soil microbiomes. Ecosphere. 2018;9:e02235.

He Z, Chen H, Liang L, Dong J, Liang Z, Zhao L. Alteration of crop rotation in continuous Pinellia ternate cropping soils profiled via fungal ITS amplicon sequencing. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2019;686:522–9.

Li C, Chen G, Zhang J, Zhu P, Bai X, Hou Y, et al. The comprehensive changes in soil properties are continuous cropping obstacles associated with American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) cultivation. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5068.

Yao Y, Yao X, An L, Bai Y, Xie D, Wu K. Rhizosphere bacterial community response to continuous cropping of Tibetan barley. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:551444.

Huang W, Sun D, Fu J, Zhao H, Wang R, An Y. Effects of continuous sugar beet cropping on rhizospheric microbial communities. Genes. 2019;11:13.

Qu B, Liu Y, Sun X, Li S, Wang X, Xiong K, et al. Effect of various mulches on soil physico-chemical properties and tree growth (Sophora japonica) in urban tree pits. PLoS One. 2019;2018(14):e0210777.

Xing S, Wang J, Zhou Y, Bloszies SA, Tu C, Hu S. Effects of NH4+ −N/NO3- -N ratios on photosynthetic characteristics, dry matter yield and nitrate concentration of spinach. Exp Agric. 2015;51:151e160.

Zhang WW, Wang C, Xue R, Wang LJ. Effects of salinity on the soil microbial community and soil fertility. J Integr Agric. 2019;18:1360–8.

Li T, Liu T, Zheng C, Kang C, Yang Z, Yao X, et al. Changes in soil bacterial community structure as a result of incorporation of Brassica plants compared with continuous planting eggplant and chemical disinfection in greenhouses. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173923.

Jiang YJ, Liang YT, Li CM, Wang F, Sui YY, Su YN, et al. Crop rotations alter bacterial and fungal diversity in paddy soils across East Asia. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;95:250–61.

Liu X, Herbert S, Hashemi A, Zhang X, Ding G. Effects of agricultural management on soil organic matter and carbon transformation - a review. Plant Soil Environ. 2006;52:531–43.

Nayyar A, Hamel C, Lafond G, Gossen BD, Hanson K, Germida J. Soil microbial quality associated with yield reduction in continuous-pea. Appl Soil Ecol. 2009;43:115–21.

Lyu J, Jin L, Jin N, Xie J, Xiao X, Hu L, et al. Effects of different vegetable rotations on fungal community structure in continuous tomato cropping matrix in greenhouse. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:829.

Ge Y, Zhang JB, Zhang LM, Yang M, He JZ. Long-term fertilization regimes affect bacterial community structure and diversity of an agricultural soil in northern China. J Soils Sediments. 2008;8(1):43–50.

Chen QL, Ding J, Zhu YG, He JZ, Hu HW. Soil bacterial taxonomic diversity is critical to maintaining the plant productivity. Environ Int. 2020;140:105766.

Xiong W, Zhao Q, Xue C, Xun W, Zhao J, Wu H, et al. Comparison of fungal community in black pepper-vanilla and vanilla monoculture systems associated with vanilla Fusarium wilt disease. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:117.

van Elsas JD, Chiurazzi M, Mallon CA, Elhottova D, Kristufek V, Salles JF. Microbial diversity determines the invasion of soil by a bacterial pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1159–64.

Song X, Pan Y, Li L, Wu X, Wang Y. Composition and diversity of rhizosphere fungal community in Coptis chinensis Franch. Continuous cropping fields. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193811.

Li N, Gao D, Zhou X, Chen S, Li C, Wu F. Intercropping with potato-onion enhanced the soil microbial diversity of tomato. Microorganisms. 2020;8:834.

Lupwayi NZ, Rice WA, Clayton GW. Soil microbial diversity and community structure under wheat as influenced by tillage and crop rotation. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:1733–41.

Bell TH, Yergeau E, Maynard C, Juck D, Whyte LG, Greer CW. Predictable bacterial composition and hydrocarbon degradation in Arctic soils following diesel and nutrient disturbance. ISME J. 2018;7:1200–10.

Pathan SI, Scibetta S, Grassi C, Pietramellara G, Orlandini S, Ceccherini MT, et al. Response of soil bacterial community to application of organic and inorganic phosphate based fertilizers under vicia faba L. cultivation at two different phenological stages. Sustainability. 2020;12:9706.

Fudou R, Iizuka T, Sato S, Ando T, Shimba N, Yamanaka S. Haliangicin, a novel antifungal metabolite produced by a marine myxobacterium. 2. Isolation and structural elucidation. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2001;54:153–6.

Cao S, Liang QW, Nzabanita C, Li YZ. Paraphoma root rot of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) in Inner Mongolia. China Plant Pathol. 2020;69:231–9.

Ewa O, Agnieszka H. Mortierella species as the plant growth-promoting fungi present in the agricultural soils. Agriculture. 2020;11:7.

Paudel B, Bhattarai K, Bhattarai HD. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of two polyketides from lichen-endophytic fungus Preussia sp. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2018;73:161–3.

Barrera VA, Martin ME, Aulicino M, Martínez S, Chiessa G, Saparrat M, et al. Carbon-substrate utilization profiles by Cladorrhinum (Ascomycota). Rev Argent Microbiol. 2019;51:302–6.

Yuan QS, Xu J, Jiang W, Ou X, Wang H, Guo L, et al. Insight to shape of soil microbiome during the ternary cropping system of Gastradia elata. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:108.

Chi WC, Chen W, He CC, Guo SY, Cha HJ, Tsang LM, et al. A highly diverse fungal community associated with leaves of the mangrove plant Acanthus ilicifolius var. xiamenensis revealed by isolation and metabarcoding analyses. Peer J. 2019;7:e7293.

Luo L, Guo C, Wang L, Zhang J, Deng L, Luo K, et al. Negative plant-soil feedback driven by re-assemblage of the rhizosphere microbiome with the growth of Panax notoginseng. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1597.

Xu X, Han L, Zhao L, Chen X, Miao C, Hu L, et al. Echinosporin antibiotics isolated from Amycolatopsis strain and their antifungal activity against root-rot pathogens of the Panax notoginseng. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2019;64:171–5.

Guarnaccia V, Martino I, Gilardi G, Garibaldi A, Gullino L. Colletotrichum spp. causing anthracnose on ornamental plants in northern Italy. J Plant Pathol. 2020; (prepublish). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42161-020-00684-2.

Acknowledgements

We especially thank Tan Qingqing and Shi Xueqin from Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences for help in microbial sequencing.

Research involving plants

Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) provided all plant materials used in this study. No specific permissions were required for the collection of those samples for research purposes in accordance with the institutional, national and international guidelines. In addition, our samples were all taken from B. chinense farmland. We confirm that the field research did not involve endangered or protected species.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology to Boost Economy 2020 (No. SQ2020YFF0426286 and No. SQ2020YFF0426541).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Professor GDM designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. Professor CHU, LL and GYN collected the rhizosphere soil of Bupleurum chinense. LL carried out the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. Professor BX and ZQF assisted in microbial sequencing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplement Table 1

. High-throughput results for bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere soil of Bupleurum chinese under different cropping practices.

Additional file 2: Supplement Figure 1

. Rarefaction curves of Bupleurum chinense samples in different cropping practices. (A) Bacteria, (B) Fungi.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Cao, H., Geng, Y. et al. Response of soil microecology to different cropping practice under Bupleurum chinense cultivation. BMC Microbiol 22, 223 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02638-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02638-3