Abstract

Background

Metagenomic studies confirm that obesity is associated with a composition of gut microbiota. There are some controversies, however, about the composition of gut microbial communities in obese individuals in different populations. To examine the association between body mass index and microbiota composition in Ukrainian population, fecal concentrations of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio were analyzed in 61 adult individuals.

Results

The relative abundance of Actinobacteria was small (5–7%) and comparable in different BMI categories. The content of Firmicutes was gradually increased while the content of Bacteroidetes was decreased with increasing body mass index (BMI). The F/B ratio also raised with increasing BMI. In an unadjusted logistic regression model, F/B ratio was significantly associated with BMI (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1,09–1,38). This association continued to be significant after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, tobacco smoking and physical activity (OR = 1.33, 95% CI 1,11–1,60).

Conclusions

The obtained data indicate that obese persons in Ukraine adult population have a significantly higher level of Firmicutes and lower level of Bacteroidetes compared to normal-weight and lean adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The epidemic of obesity around the world has become an important public health issue, with serious psychological and social consequences [1, 2]. Obesity is recognized as a multifactorial disorder which is a result of the interaction of host and environmental factors, occurring when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure over time [1]. The gut microbiota is known to play an important role in energy homeostasis [3, 4]. Metagenomic studies confirm that gut microbiota in obese subjects is more efficient than that in lean subjects at recovering the energy from resistant dietary components [5, 6]. Previous animal studies provided insight into the underlying mechanisms of that phenomenon. There are: (1) increased caloric intake from indigestible polysaccharides, combined with effect on hepatic de novo lipogenesis via carbohydrate and sterol response-element binding proteins; (2) enhanced cellular uptake of fatty acids and storage of triglycerides in adipocytes via suppression of intestinal expression of fasting-induced adipocyte factor which is circulating inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase; (3) suppression the skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation through a metabolic pathway involving phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; and (4) interaction between short chain fatty acids products of microbial fermentation of dietary polysaccharides and G-protein-coupled receptor 41 which results in increased levels of enteroendocrine cell-derived hormone PYY, thus, reducing gut motility with subsequently increased intestinal transit time and absorption rate of short-chain fatty acids [7,8,9]. Microbiota can also promote obesity and metabolic syndrome by inducing low-grade inflammation [7, 10]. Currently, gut microbiota is increasingly considered as a “metabolic organ” greatly affecting the organism’s metabolism [11]. According to this point of view, there is plausible reason to suppose that differences in gut microbiota may be linked to energy homeostasis, thus predicting that obese and lean individuals have distinct microbiota composition, with measurable difference in the ability to extract energy from the food and to store those energy as the fat [12].

Presently, changes in intestinal microbial composition are believed to be an important causal factor in development of obesity [13]. The most common organisms in human gut microbiota are members of the gram-positive Firmicutes and the gram-negative Bacteroidetes phyla, with several others phyla, including the Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia, that are present at subdominant levels [14]. Data obtained from animal models revealed consistent differences in the two major bacterial phyla with significant increase of the Firmicutes and decrease of the Bacteroidetes levels in ob/ob compared to wild-type mice despite a similarity in their diet and activity levels [15]. Consistently with animal data, numerous human studies have consistently demonstrated that the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) proportion is increased in obese people compared to lean people, and tend to decrease with weight loss (for reviews, see [16,17,18]). Several studies, however, have produced conflicting results. Some investigations have failed to find significant differences in the F/B ratio between lean and obese humans at both baseline level and after the weight loss [19,20,21,22,23,24]. In some studies, the fecal concentrations of Bacteroides were positively correlated with body mass index (BMI) [25], and predominance of Bacteroidetes in overweight and obese individuals was demonstrated [26]. Most likely, these differences can be due to different environmental influences, including diet, physical activity, as well as socio-economic impacts [27]. Other bacterial phyla such as the Actinobacteria phylum, which is comprised of the Bifidobacterium genus as well as other genera, can also play role in weight gain and obesity. Indeed, in an investigation of gut microbiota of lean and obese twins, higher levels of Actinobacteria were found in obese subjects [28].

The associations between body weight, weight loss and changes in major bacterial groups have not been studied up to now in populations of many countries around the world, including Ukraine. The aim of present study was to assess the differences in the composition of major phyla of gut microbiota in Ukraine adults with different BMI.

Methods

Study population

The fecal samples were obtained from 61 healthy adult individuals (mean age 44.2 years) during the period from March to May 2016 (Additional file 1: Table S1). These subjects were grouped into four groups on the basis of their BMI: those with a BMI <18.5 kg/m2 (underweight persons), those with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 (normal persons), those with a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2 (overweight persons), and those with a BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2 (obese persons). Exclusion criteria were: history of oncology or endocrinology disease, anorexia, psychiatric disorders, and acute relapse of any chronic disease. Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of studied subjects are presented in Table 1.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Fresh stool samples were provided by each subject in a stool container on site. Within 10 min upon defecation, the fecal sample was aliquoted and aliquots were immediately stored at 20 °C for 1 week until DNA isolation. DNA was extracted from 1.5–2 frozen stool aliquots using the phenol-chloroform method by protocol [29]. DNA was finally eluted in 200 μl elution buffer. The DNA quantity and quality was measured by NanoDrop ND-8000 (Thermo Scientific, USA). Samples with a DNA concentration less than 20 ng or an A 260/280 less than 1.8 were subjected to ethanol precipitation to concentrate or further purified, respectively, to meet the quality standards.

Oligonucleotide primers

Quantification of different taxa by qPCR using primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene, specific for Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes, as well as universal primers was performed. The primer sequences were:

Bacteroidetes:

798cfbF AAACTCAAAKGAATTGACGG (Forward).

and cfb967R GGTAAGGTTCCTCGCGCTAT (Reverse),

Firmicutes:

928F–firm TGAAACTYAAGGAATTGACG (Forward).

and 1040FirmR ACCATGCACCACCTGTC (Reverse),

Actinobacteria:

Act920F3 TACGGCCGCAAGGCTA (Forward).

and Act1200R TCRTCCCCACCTTCCTCCG (Reverse),

and universal bacterial 16S rRNA sequences:

926F AAACTCAAAKGAATTGACGG (Forward).

and 1062R CTCACRRCACGAGCTGAC (Reverse).

PCR amplification

PCR reaction was performed in real-time thermal cycler Rotor-Gene 6000 (QIAGEN, Germany). The PCR reaction conditions consisted of an initial denaturing step of 5 min at 95 °C, 30 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, annealing for 15 s and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min. Every PCR reaction contained 0.05 units/μl of Taq polymerase (Sigma Aldrich), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.4 μM of each primer, 1× buffer, ~10 ng of DNA and water to 25 μl [30]. Samples were amplified with all primer pairs in triplicates. The Cts (univ and spec) were the threshold cycles registered by the thermocycler. The average Ct value obtained from each pair was transformed into percentage with the formula [28].

Identification of microbial composition

Determination of microbial composition at the level of major microbial phyla was carried out by identification of total bacterial DNA, and DNA of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria was performed with quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), using gene-targeted primers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the software STATISTICA 11.0. Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to test the normality of the distribution of all the quantitative variables studied. Since variables did not followed normal distribution, non-parametric methods were selected for further analysis of the data such as Spearman’s correlation and multivariate logistic regression. To identify the statistical difference among the BMI categories, median abundances of each phylum were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results

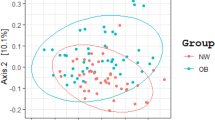

The relative abundance of the major microbial phyla substantially varied between different BMI categories. The relative abundance of Actinobacteria was small (5–7%) and comparable in different BMI categories. The content of Firmicutes was gradually increased, while the content of Bacteroidetes was decreased with increasing BMI; the F/B ratio also raised with increasing BMI (Table 2, Figs. 1 and Fig. 2).

The lower and upper quartiles are given in parenthesis after the median values. To identify the statistical difference among the BMI categories, median abundances were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

The age and sex composition was different in various BMI groups (see Table 1). So, they could be confounding factors and affect the association between F/B ratio and BMI. Therefore, the adjustment for these factors as well as for smoking and physical activity levels was performed by multivariate logistic regression model. In an unadjusted logistic regression model, F/B ratio was significantly associated with BMI. Those persons who had F/B ratio ≥ 1, were 23% more likely to be overweight than those who had F/B ratio < 1 (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1,09–1,38, p < 0.0001). This association continued to be significant after adjusting for all confounders examined (OR = 1.33, 95% CI 1,11–1,60, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Consistently with many other studies [16,17,18, 31], we found significant increase in relative abundance of Firmicutes and higher F/B ratio in overweight and obese persons in Ukraine population. It is well known from many animal and human studies that obesity is associated with a composition of gut microbiota. There are some controversies, however, about significance of the F/B ratio, as well as about the impact of Actinobacteria level, on the development of obesity. A possible explanation for our findings is that Firmicutes are more effective as an energy source than Bacteroidetes, thus promoting more efficient absorption of calories and subsequent weight gain [5, 6]. In a study by Turnbaugh et al. [27] conducted in obese and lean twins, it has been shown that Firmicutes were dominant in the microbiomes of obese subjects, which were also enriched with genes known to be associated with nutrient transporters, while a higher relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and an enrichment of genes linked to carbohydrate metabolism was found in microbiomes of lean twins.

Results from several studies, however, are inconsistent with these findings. For example, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes was shifted in favor of the Bacteroidetes in overweight and obese subjects in the Schwiertz et al. [26] research. Another possible explanation for our findings could be the association between the relative proportion of gut anaerobic bacteria and blood glucose levels. Indeed, higher blood glucose levels were found to be negatively associated with relative proportion of Bacteroides in the gut of elderly people [32]. It seems important because higher blood glucose level is key component of metabolic syndrome. In addition, the characteristics of microbiome composition revealed in our study could, at least partly, be explained by the dietary habits in the Ukraine population. In particular, they likely can be attributed to the consumption of rye bread which is known to be more commonly eaten in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe, as well as of pork fat (“salo”). In future studies, we plan to investigate the dietary effects on the intestinal microbiota composition in the population of Ukraine.

One limitation of our study is that analyses were performed in stool samples, whereas the main part of nutrients is known to be absorbed in small intestine. The analysis of proximal gut microbiota may be more appropriate for investigation of the effects of gut bacteria on body weight and metabolic changes [21, 25]. These issues should be addressed in future research. In addition, we plan further investigation of the link between BMI and microbiome composition in Ukrainian population at the lower taxonomic levels.

Conclusion

The data obtained in our study indicate that obese persons in Ukrainian adult population have a significantly higher level of Firmicutes and lower level of Bacteroidetes compared to normal-weight and lean adults. These findings from Ukraine population are consistent with findings from other populations.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- F/B ratio:

-

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio

- PAL:

-

Physical activity level

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

References

Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Peters JC. Energy Balance and Obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:126–32.

Apovian CM. The obesity epidemic - understanding the disease and the treatment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:177–9.

Bakker GJ, Zhao J, Herrema H, Nieuwdorp M. Gut microbiota and energy expenditure in health and obesity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(Suppl 1):S13–9.

Gérard P. Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:147–62.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–31.

Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan ZE, Kang DW, DiBaise JK. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:201–14.

Rial SA, Karelis AD, Bergeron KF, Mounier C. Gut microbiota and metabolic health: the potential beneficial effects of a medium chain triglyceride diet in obese individuals. Nutrients. 2016;8:281.

den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–40.

Festi D, Schiumerini R, Eusebi LH, Marasco G, Taddia M, Colecchia A. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16079–94.

Chassaing B, Gewirtz AT. Has provoking microbiota aggression driven the obesity epidemic? BioEssays. 2016;38:122–8.

Caitriona M, Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:295–308.

Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4153–8.

Sonnenburg JL, Bäckhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535:56–64.

Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–8.

Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11070–5.

Sweeney TE, Morton JM. The human gut microbiome: a review of the effect of obesity and surgically induced weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:563–9.

Mathur R, Barlow GM. Obesity and the microbiome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:1087–99.

Barlow GM, Yu A, Mathur R. Role of the gut microbiome in obesity and diabetes mellitus. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30:787–97.

Ismail NA, Ragab SH, ElBaky AA, Shoeib ARS, Alhosary Y, Fekry D. Frequency of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in gut microbiota in obese and normal weight Egyptian children and adults. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:501–7.

Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, Parameswaran P, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2365–70.

Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, Ince J, Johnstone AM, Louis P, et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1720–4.

Hu HJ, Park SG, Jang HB, Choi MK, Park KH, Kang JH, et al. Obesity alters the microbial community profile in Korean adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134333.

Million M, Angelakis E, Maraninchi M, Henry M, Giorgi R, Valero R, et al. Correlation between body mass index and gut concentrations of Lactobacillus reuteri, Bifidobacterium animalis, Methanobrevibacter smithii and Escherichia coli. Int J Obes. 2013;37:1460–6.

Karlsson CL, Onnerfält J, Xu J, Molin G, Ahrné S, Thorngren-Jerneck K. The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;202:257–61.

Ignacio A, Fernandes MR, Rodrigues VA, Groppo FC, Cardoso AL, Avila-Campos MJ, et al. Correlation between body mass index and faecal microbiota from children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:e1–8.

Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, et al. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:190–5.

Dugas LR, Fuller M, Gilbert J, Layden BT. The obese gut microbiome across the epidemiologic transition. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2016;13:2.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4.

Zhang BW, Li M, Ma LC, Wei FW. A widely applicable protocol for DNA isolation from fecal samples. Biochem Genet. 2006;44:503–12.

De Gregoris TB, Aldred N, Clare AS, Burgess JG. Improvement of phylum-and class-specific primers for real-time PCR quantification of bacterial taxa. J Microbiol Meth. 2011;86:351–6.

Kasai C, Sugimoto K, Moritani I, Tanaka J, Oya Y, Inoue H, et al. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;11:100.

Sepp E, Kolk H, Lõivukene K, Mikelsaar M. Higher blood glucose level associated with body mass index and gut microbiota in elderly people. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2014;25 doi:10.3402/mehd.v25.22857.

Hills AP, Mokhtar N, Byrne NM. Assessment of physical activity and energy expenditure: an overview of objective measures. Front Nutr. 2014;1:5.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Natalya Koshel for valuable statistic advice.

Funding

This work was funded by National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine and performed within the frame of the research program No. 0113 U002119 of D. F. Chebotarev Institute of Gerontology, Kiev, Ukraine. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this report are included within the article and in an additional file.

Authors’ contributions

AK, GS, VP, AD, ST were involved in experimental design. GS, LB, KP, YG, MR and LS assembled the population and performed the sampling. AK, VM and OL were involved in the molecular procedures. AK, GS, KP, YG and AV analyzed the data. AK, GS, LB, KP, MR and AV wrote and edited the paper. AV performed final editing of the paper. All authors have read and approve of the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research complied with the standards and recommendations for biomedical research involving human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964 and the 59th Meeting, Seoul, 2008. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment with approval by the Ethics Committee of D. F. Chebotarev Institute of Gerontology, NAMS of Ukraine and O.O. Bogomolets National Medical University.

All participants gave written informed consent to provide a stool sample and to the availability of the stored samples for additional bioassays after the study protocol was fully explained.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Provides the individual data on the gender, age, anthropometric indices and relative abundance of the major microbial phyla in the study subjects. (XLSX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koliada, A., Syzenko, G., Moseiko, V. et al. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol 17, 120 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1027-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1027-1