Abstract

Background

Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep in China are characterized by fat tails and thin tails, respectively. Several transcriptomes have been conducted in different sheep breeds to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) underlying this trait. However, these studies identified different DEGs in different sheep breeds.

Results

Hence, RNA sequencing was performed on Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep. We obtained a total of 45.57 and 43.82 million sequencing reads, respectively. Two libraries mapped reads from 36.93 and 38.55 million reads after alignment to the reference sequences. 2108 DEGs were identified, including 1247 downregulated and 861 upregulated DEGs. GO and KEGG analyses of all DEGs demonstrated that pathways were enriched in the regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes and terms related to the chemokine signalling pathway, lysosomes, and glycosaminoglycan degradation. Eight genes were selected for validation by RT–qPCR. In addition, the transfection of BMP2 overexpression into preadipocytes resulted in increased PPAR-γ expression and expression. BMP2 potentially induces adipogenesis through LOX in preadipocytes. The number of lipid drops in BMP2 overexpression detected by oil red O staining was also greater than that in the negative control.

Conclusion

In summary, these results showed that significant genes (BMP2, HOXA11, PPP1CC and LPIN1) are involved in the regulation of adipogenesis metabolism and suggested novel insights into metabolic molecules in sheep fat tails.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sheep are one of the main livestock resources around the world, consuming the produce meat, milk, wool, and fur [1]. Fat-tailed sheep make up a quarter of the world's sheep population. In China, there are more than 98 indigenous sheep breeds, 80% of which are fat-tailed sheep. Fat tails are also food for humans. However, with the increase in people's life standards, mutton consumption has been increasing, and the utilization rate of fat in sheep is lower. The intensity of fat deposition in the sheep tail is higher than that in the rest of the body [2]. Conversely, excessive fat deposition affects the feed conversion rate of sheep, which increases the cost of farmers' breeding. In production, a large amount of fat tail is directly discarded, forming a considerable amount of waste. Reducing fat deposition can produce leaner meat. It is important for the sheep industry for pastures to increase economic profits [3]. Consequently, this provides a better understanding of the molecular mechanism of lipogenesis in sheep breeding and control of carcass fat [4].

In recent years, several genomic approach studies have been conducted to reveal the important genes of the fat tail phenotype in different sheep breeds [5]. BMP2 and PDGFD are likely potential genes related to fat deposition in the tails of sheep [6, 7]. In addition to these data, potential genes involved in the development of the fat tail were analysed in fat-tailed breeds. Mohammad and colleagues [8] identified some genes as important candidates associated with fat-tailed deposition of sheep, such as HOXA10, ACSS2, ELOVL6, BMP6 and FABP4. Comparing Lanzhou fat-tailed sheep with two others thin-tailed sheep by using RNA-seq, CREB1, WDR92 and ETAA1 are potentially associated with fat tail development [5]. These results have provided abundant information for elucidating the genetic mechanism of fat deposition among these breeds. Nonetheless, the complex genetic factors associated with fat tail development also need further study. Therefore, it is important to study fat deposition in Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep.

The transcriptome provides an opportunity to reveal the underlying mechanisms of fat deposition in sheep [8]. In addition, some studies have compared various fat deposition in the transcriptomes of different species, such as pigs [9], cattle [10] and humans [11]. Therefore, RNA-Seq was used to identify DEGs, and regulatory pathways related to sheep fat deposition between Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep breeds. Combined with our previous analysis results [12,13,14], BMP2 overexpression in preadipocytes provides a theoretical basis for the genetic improvement of sheep tail fat.

Results

RNA-seq data summary

Two cDNA libraries of adipose tissue in tails from Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep were sequenced. A total of 45.57 million paired-end raw reads were obtained from six sheep samples. The size of each sample ranged from 43.02 to 44.65 million per sample. HISAT2 and Bowtie2 tools compared 86.03 and 65.41% clean reads with reference genomes, respectively. Moreover, clean reads were mapped to the reference genome (Ovis_v3.1). The RNA-sequencing and mapping information of the samples is shown in Table 1. These data were preliminarily analysed. The sample correlation was performed with the Pearson correlation coefficients based on gene expression levels, and these coefficients were reflected in the form of a heatmap (Fig. 1).

Differential expressed genes analysis

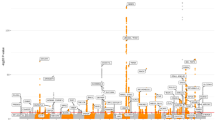

RNA-Seq analysis of the two sheep breeds showed a total of 2108 genes detected using the reference genome. The genes with |FRKM|≥ 1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.01 were identified as DEGs, resulting in 1247 upregulated and 861 downregulated DEGs in the Hu sheep breeds. The top 8 differentially expressed genes involved in fat deposition were S100A8, CLDN, TBX15 and HGF, which were upregulated in Hu sheep, while SELENBP1, MSC, EIF4EBP4 and GRB10 were downregulated in Hu sheep (Fig. 2, Table S1).

Eight DEGs were selected for RT–qPCR to validate our RNA-seq data. Among these DEGs, the trends of gene expression changes were consistent with the RNA-seq results (Fig. 2b).

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to obtain the biological relationships of the DEGs. The results of GO terms showed a nominal significance of Q-value < 0.01 in that 134 GO terms were enriched in the three groups (Fig. 3a). These included lipids metabolic process (GO:0,006,629), fatty acid metabolic process (GO:0,006,631) and cellular lipid metabolic process (GO:0,044,255). KEGG also identified 13 significant pathways (Q-value < 0.01), including regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes (Q-value = 2.04E-04), carbon metabolism (Q-value = 1.13E-04), thermogenesis (Q-value = 1.35E-04) and glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (Q-value = 8.35E-04) (Fig. 3b). These pathways were involved in fat metabolism or energy metabolism. ClueGO functional analysis of these potential DEGs also constructed a plausible pathway network for fat deposition in sheep [15]. A total of 219 terms were enriched. ClueGO analysis showed that most DEGs were regulated by fatty acid derivative metabolic processes (P value Bonferroni = 0.0096), regulation of plasma lipoprotein particle levels (P value Bonferroni = 0.0249) and lipid oxidation (P value Bonferroni = 0.0294) (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, some pathways associated with cold stimulation were also enriched, such as regulation of cold-induced thermogenesis (P value Bonferroni = 1.8618E-06), cold-induced thermogenesis (P value Bonferroni = 1.8618E-06) and temperature homeostasis (P value Bonferroni = 6.3048E-06).

a GO enrichment for differentially expressed genes in adipose tissue of Hu sheep tail and Tibetan sheep; b KEGG enrichment for differentially expressed genes in adipose tissue of Hu sheep tail and Tibetan sheep; c Mechanism of fat deposition signalling pathway in differentially expressed genes; d The top 40 hub differentially expressed genes identified in PPI networks

To further determine the functional relationship to understand the DEGs, a PPI network formed interactions between upregulated and downregulated DEGs. According to node degree, we identified hub genes among these important DEGs. For better visualization, we reconstructed the interactors of the top 40 DEGs (Fig. 3d) using the cytohubba plug-in. GPI, ACACA, ACSS2, TTN, and FASN were upregulated in Hu sheep, and WAS, LPIN1, GFAP, and FN1 were downregulated in Hu sheep.

The effect of BMP2 on adipogenesis induction

Based on our previous studies, we applied selection signal analysis to identify selection signals in sheep with different tail types [12]. These two methods found 43 candidate genes that may potentially be related to fat tail development, including BMP2, HOXA11 and PPP1CC, which may play important roles in fat tail formation. Among these genes, BMP2 is also strongly selected in the largest region by hapFLK [12]. Fat-tailed fixation is caused by a selective sweep near the retrotransposition hotspot on chromosome 13, and this diversity affects BMP2 expression [14, 16]. We performed western blotting of BMP2 in the tail fat of Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep, and the results showed that BMP2 was highly expressed in Hu sheep (Fig. 4a). This was therefore selected for BMP2 overexpression in preadipocytes. BMP2 overexpression lentivirus transfected into preadipocytes (Fig. 4b), and after induced differentiation, BMP2 overexpression also increased the mRNA levels of PPAR-γ and LOX when compared with NC at 0 d (P value < 0.05) (Fig. 4c, d). There was no difference at 1, 3 and 5 days. Sheep preadipocytes on day 5 were stained with oil red O. Many small lipid droplets were stained red, and lipid rings were visible. The number of lipid drops in the BMP2 overexpression group was greater than that in the NC group (Fig. 4e), which showed that fat deposition in the sheep tail was increased by BMP2 overexpression.

a The regulation of the protein level of BMP2 in adipose tissue of Hu sheep tail (H1, H2 and H3) and Tibetan sheep tail (Z1, Z2 and Z3). We cut 30-70 kDa of protein to transferred onto a PVDF membrane. b Relative expression of BMP2 in BMP2 over-expression and NC. c Relative expression of PPAR-γ in BMP2 over-expression and NC. d Relative expression of LOX in BMP2 over-expression and NC. e Oil red O staining when BMP2 was overexpressed in sheep preadipocytes

Discussion

Sheep tail fat deposition has a complex genetic regulation mechanism, which is determined by the environment and genes. Fat-tails are used to save energy in food plentiful seasons. During cold winters and in harsh environments, it provides the necessary energy to help sheep subsist [3]. Tail adipose tissue is an important tissue site for fat deposition in fat tail sheep. Research on the tail cutting of Mongolian sheep and Lanzhou large-tailed sheep found that the fat originally deposited in the tail was blocked by the tail fat metabolic pathway, and part of the fat was transferred and deposited in the rest of the body, mainly subcutaneous fat and intra-abdominal fat [17]. Therefore, the study of the fat tail is also an important material in the study of fat metabolism. Hu sheep are a short fat-tailed sheep breed and are also a good model to study fat deposition in the tail. Previous studies have mainly focused on the differential gene expression patterns or molecular genetic mechanisms among different sheep [1, 2, 8, 9, 18]. The mechanism by which mRNA regulates fat deposition is largely unknown.

In this study, a total of 2108 DEGs were identified as differentially expressed in Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep using RNA-seq. The purpose of this study was to assess the expression differences between fat-tailed and thin-tailed transcripts in sheep, which may contribute to a better understanding of the regulation of fat deposition metabolism in sheep. Through GO and KEGG enrichment analyses, we identified 134 and 13 pathways, respectively. DEGs were mostly directly or indirectly related to metabolic activity pathways, such as fatty acid metabolic processes, regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes and lipid metabolic processes [19]. This result implies that the molecular mechanism of fat deposition in the sheep tail is controlled by interactions that occur in a complex network of genes. Fat deposition in sheep tails may be regulated by multiple genes [20]. In this study, some upregulated DEGs were related to lipid metabolism, including S100A8, BMP2, ADIPOQ, DGAT2, VLDLR, ELOVL6, GPI and ACACA. S100A8 plays an important role in the inflammatory responses of obese adipose tissue and contributes to the pathogenesis of obesity [21]. ADIPOQ is mainly secreted by adipose tissue and is a kind of adipocytokine [22]. ADIPOQ is also a major component in lipid metabolism by inhibiting lipid synthesis and promoting fatty acid oxidation [22, 23]. This gene was highlighted in transcriptome analysis of sheep fat deposition [1, 8, 24]. In addition, genetic variation in ADIPOQ is associated with fat deposition in pigs [25] and meat marbling in cattle [26]. DGAT2 is crucial in catalysing the production of triacylglycerol [27]. DGAT2 was also identified to affect fat deposition in sheep [8] and pigs [28]. VLDLR is involved in triglyceride metabolism [29] and is associated with fat deposition in pigs [9]. ELOVL6 plays an important role in controlling the overall balance of fatty acid components [30] and is also found in pigs [30] and sheep [2]. ACACA is a key regulator of lipogenesis in the adipose tissue of animals [31, 32]. GPI acts in the glucose pathway into pentose phosphate and produces NADPH, which is necessary for lipid metabolism [33, 34]. In our study, ACACA and GPI were selected in the PPI network, which may reveal that upregulation of these DEGs may induce fat deposition in the Hu sheep breed. In a previous study, we also identified BMP2 as playing an important role in sheep tail formation [12, 13]. A previous study also showed that BMP2 promotes the expression of PPAR-γ in preadipocytes and promotes the differentiation of preadipocytes from sheep [35]. In our study, the result of oil red O at 5 days showed that fat deposition in the sheep tail was increased by BMP2 overexpression. This finding confirms that BMP2 promoted differentiation of preadipocytes. The results are consistent with previous results [35]. Yuan et al. also showed that BMP2 was associated with fat deposition [12]. Moreover, LOX is a bona fide downstream target gene of the BMP signalling pathway [36]. During adipocyte lineage commitment, LOX is induced by BMP2/4 [37]. These results were similar to our studies. BMP2 overexpression in preadipocytes promoted PPAR-γ and LOX expression at 0 days. BMP2 potentially induces adipogenesis through LOX in preadipocytes. The present results failed to demonstrate the exact mechanism of LOX expression promoted by BMP2. Future studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which LOX is promoted by BMP2 in preadipocytes to pinpoint the true induction of adipogenesis.

Furthermore, GO terms revealed DEGs enriched in cold-induced thermogenesis. The cold-induced thermogenesis pathway is important in the regulation of adipogenesis and lipid metabolism [38, 39]. Cold exposure activates brown fat to stimulate lipolysis but also leads to an increase in fatty acid synthesis within tissues [40]. Interestingly, CPT2, LCN2, PPARGC1A, UCP2 and HOXC10 were enriched in GO terms related to thermogenesis. Among these genes, CPT2 is important for fatty acid oxidation [41] and is widely expressed as an energy-producing tissue [42]. CPT2 was also identified with RNA-seq in Lori-Bakhtiari and Zel sheep [2]. LCN2 may act as an anti-obesity agent by upregulating thermogenic markers, leading to browning in white adipose tissue [43]. PPARGC1A plays a role in stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and regulating glucose and fatty acid metabolism [44, 45]. Moreover, UCP2 is well known to be involved in resistance to diet-induced obesity [46]. Previous studies have proven that HOX genes are associated with anterior to posterior vertebrate axial morphology [17, 18]. The caudal regions of short thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep differ significantly, characterized by significant changes in fat mass, which may largely depend on the number of vertebrate caudal vertebrae and require further study [18]. In our study, HOXC12, HOXA6, HOXA4, HOXD13, HOXB2 and HOXD10 were identified as DEGs in Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep. In addition, HOXA6, HOXB2, HOXD10, BMP7 and TBX15 were enriched in embryonic skeletal system development terms. BMP7 can induce brown adipogenesis, and overexpression in adipose tissue induces white adipogenesis [47]. TBX15 is involved in encoding phylogenetically conserved transcription factors that regulate developmental processes and plays a vital role in regulating muscle metabolism and glycolytic fibre identity [48, 49].

Conclusion

In this study, transcriptome analysis was first performed in Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep. Some GO terms and pathways associated with lipid deposition were identified. PPI network analysis showed that DEGs were significantly involved in lipid metabolism. These DEGs may be important in fat tail metabolism in sheep. Among these DEGs, BMP2 potentially induces adipogenesis through LOX in preadipocytes. The exact mechanism also needs to be studied in further investigations. In short, these findings provide a new theoretical basis for the study of the mechanism of fat-tailed sheep.

Materials and methods

Animals and sample collection

Six male sheep (1.5 years old with approximately equivalent weights) from each purebred Hu sheep (H1, H2, H3, Yongdeng, Gansu) and Tibetan sheep (Z1, Z2, Z3, Yushu, Qinghai) were used in this study. Adipose tissue from tails of the sheep were collected and washed with 0.9% NaCl and then frozen in liquid nitrogen until RNA was extracted.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from fat tissue samples using the Standard Sensitivity RNA Analysis Kit (15 nt) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified, and the purity of the samples was determined using the Fragment Analyser to evaluate the 28S/18S ratio. All samples with an OD260/280 ratio greater than 1.9 and 28S/18S ratio > 1.2 were sequenced by BGI (Beijing, China). RON and RNA integrity number (RIN) were measured, and only RIN/RQN ratios greater than 7.5 were used for cDNA library construction. Then, cDNA libraries were sequenced on the BGISEQ-500 platform by a paired-end strategy. The raw data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive with the indicated accession codes (BioProject ID: PRJNA792697).

Quality control and mapping genome to identified DEGs

We carried out quality control on raw data to detect common issues using the SOAPnuke v1.4.0 program [50]. Then, raw reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic to remove adapter sequences and poly-N and low-quality sequence reads to obtain clean reads [2, 51]. Clean reads were saved in fastq format. Clean reads were processed using HISAT v2.1.0 [52], and the clean reads were aligned to Ovis_aries (Oar_v3.1). Moreover, using Bowtie v2.2.5, we built an index of the reference genome [53], and the level of expression was calculated using RSEM [54]. In addition, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using SARTools software [55]. According to the gene expression patterns, the samples were clustered, and the degree of similarity/difference between the gene expression profiles was detected [2].

Functional analysis and PPI network construction

Phyper function in R performed gene set enrichment analysis in up- or downregulated genes. The significant enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) functional terms with DEGs that showed differential expression was analysed (P value ≤ 0.01) [56]. Furthermore, the significantly DEGs were also enriched in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (P value ≤ 0.05) [57]. Among these DEGs, protein–protein interactions (PPIs) were considered in the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) [58].

Isolation of preadipocytes from adipose tissue of Hu sheep and transfection of BMP2 overexpression

The BMP2 overexpression lentivirus was constructed as described by Lu [14]. An empty lentivirus vector was used as the negative control (NC) [14]. Preadipocytes were isolated from Hu sheep tail fat (70-day-old foetus). Primary preadipocytes were cultured in vitro by collagenase digestion. The cells were incubated in complete medium at 37 ℃ for two days, and the cells were almost all adherent to the wall. Cells were cultured in a plate with 1000 µl medium (5% FBS, 1% PS) in 6-well plates, and the titration of lentiviruses was MOI = 100 of the final construct together with BMP2 overexpression in triplicate for 24 h. Then, the cells were transferred to new complete medium (10% FBS, 1% PS). When the cells showed contact inhibition, the induction differentiation medium (complete medium + 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine + 10 mg/mL insulin + 1 µM dexamethasone) was changed for 2 days. The final cells were cultured in maintenance differentiation medium (complete medium + 10 mg/mL insulin) for 2 days [59]. Cells were set as the first day when cultured with differentiation medium. RNA was extracted from cells with BMP2 overexpression and NC at various times (0, 1, 3 and 5 days).

Oil red O staining

Oil red O dye (Solarbio, China) and distilled water at a ratio of 3:2 was used to filter the mixture. Cells differentiated for 5 days were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Then, oil red O dye was added, and the cells were incubated for 15 min, washed with distilled water 2–3 times and observed and photographed under a microscope.

RT–qPCR and western blot

Reverse transcription was performed according to the instructions of the Primer Script II 1st strand kit (Takara, China). The primers were designed by Primer 5.0 (Table S2). β-actin was used as the reference gene. Three biological replicates and triplicate technical replicates were obtained. The reaction and calculation were described by Jin [60].

Fat tissues were extracted from tails of Hu sheep (H1, H2 and H3) and Tibetan (Z1, Z2 and Z3) and 1 ml RIPA lysis buffer and 1 mM PMSF (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were added to obtain the total proteins; thus, the protein concentrations were measured with the BCA method (Beyotime, China). Proteins were separated on 10% SDS–PAGE and cut 30–70 kDa of protein to transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA). The membrane was sealed with quick sealing fluid (Lablead, China) and washed with TBST (Solarbio, China) three times. Proteins were detected with rabbit monoclonal anti-β-tubulin (50 kDa, Proteintech, USA) and rabbit monoclonal BMP2 (44 kDa, Proteintech, USA). The reaction band was developed by using enhanced chemiluminescence (Epizyme, China) and images of the PVDF membrane were recorded with a JP-K600 imaging system (JiaPeng, China).

Availability of data and materials

All the RNA-seq reads have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) with the accession codes (BioProject ID: PRJNA792697).

Abbreviations

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- FPKM:

-

Fragments Per Kilobase per Million

- BMP2 :

-

Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2

- PPAR-γ :

-

Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor γ

- LOX :

-

Lysyl Oxidase

References

Li B, Qiao L, An L, Wang W, Liu J, Ren Y, Pan Y, Jing J, Liu W. Transcriptome analysis of adipose tissues from two fat-tailed sheep breeds reveals key genes involved in fat deposition. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):338.

Bakhtiarizadeh MR, Salehi A, Alamouti AA, Abdollahi-Arpanahi R, Salami SA. Deep transcriptome analysis using RNA-Seq suggests novel insights into molecular aspects of fat-tail metabolism in sheep. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9203.

Dong K, Yang M, Han J, Ma Q, Han J, Song Z, Luosang C, Gorkhali NA, Yang B, He X, et al. Genomic analysis of worldwide sheep breeds reveals PDGFD as a major target of fat-tail selection in sheep. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):800.

Han F, Li J, Zhao R, Liu L, Li L, Li Q, He J, Liu N. Identification and co-expression analysis of long noncoding RNAs and mRNAs involved in the deposition of intramuscular fat in Aohan fine-wool sheep. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):98.

Ma L, Li Z, Cai Y, Xu H, Yang R, Lan X. Genetic variants in fat- and short-tailed sheep from high-throughput RNA-sequencing data. Anim Genet. 2018;49(5):483–7.

Li X, Yang J, Shen M, Xie XL, Liu GJ, Xu YX, Lv FH, Yang H, Yang YL, Liu CB, et al. Whole-genome resequencing of wild and domestic sheep identifies genes associated with morphological and agronomic traits. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2815.

Moioli B, Pilla F, Ciani E. Signatures of selection identify loci associated with fat tail in sheep. J Anim Sci. 2015;93(10):4660–9.

Bakhtiarizadeh MR, Alamouti AA. RNA-Seq based genetic variant discovery provides new insights into controlling fat deposition in the tail of sheep. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13525.

Xing K, Wang K, Ao H, Chen S, Tan Z, Wang Y, Xitong Z, Yang T, Zhang F, Liu Y, et al. Comparative adipose transcriptome analysis digs out genes related to fat deposition in two pig breeds. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12925.

Silva-Vignato B, Coutinho LL, Poleti MD, Cesar ASM, Moncau CT, Regitano LCA, Balieiro JCC. Gene co-expression networks associated with carcass traits reveal new pathways for muscle and fat deposition in Nelore cattle. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):32.

Koh E-H, Chernis N, Saha PK, Xiao L, Bader DA, Zhu B, Rajapakshe K, Hamilton MP, Liu X, Perera D, et al. miR-30a remodels subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation to improve insulin sensitivity in obesity. Diabetes. 2018;67(12):2541–53.

Yuan Z, Liu E, Liu Z, Kijas JW, Zhu C, Hu S, Ma X, Zhang L, Du L, Wang H, et al. Selection signature analysis reveals genes associated with tail type in Chinese indigenous sheep. Anim Genet. 2017;48(1):55–66.

Zhu C, Li N, Cheng H, Ma Y: Genome wide association study for the identification of genes associated with tail fat deposition in Chinese sheep breeds. Biol Open. 2021,10(5):bio054932.

Lu Z, Liu J, Han J, Yang B: Association Between BMP2 Functional Polymorphisms and Sheep Tail Type. Animals (Basel). 2020,10(4):739.

Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman WH, Pages F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–3.

Pan Z, Li S, Liu Q, Wang Z, Zhou Z, Di R, An X, Miao B, Wang X, Hu W, et al. Rapid evolution of a retro-transposable hotspot of ovine genome underlies the alteration of BMP2 expression and development of fat tails. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):261.

Wang X, Fang C, He H, Cao H, Liu L, Jiang L, Ma Y, Liu W. Identification of key genes in sheep fat tail evolution Based on RNA-seq. Gene. 2021;781: 145492.

Kang D, Zhou G, Zhou S, Zeng J, Wang X, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Chen Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals potentially novel roles of Homeobox genes in adipose deposition in fat-tailed sheep. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14491.

Bakhtiarizadeh MR, Salami SA. Identification and Expression Analysis of Long Noncoding RNAs in Fat-Tail of Sheep Breeds. G3 (Bethesda). 2019;9(4):1263–76.

Bigham AW, Lee FS. Human high-altitude adaptation: forward genetics meets the HIF pathway. Genes Dev. 2014;28(20):2189–204.

Sekimoto R, Fukuda S, Maeda N, Tsushima Y, Matsuda K, Mori T, Nakatsuji H, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Kikuta J, et al. Visualized macrophage dynamics and significance of S100A8 in obese fat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(16):E2058-2066.

Liu R, Liu X, Bai X, Xiao C, Dong Y. Different expression of lipid metabolism-related genes in Shandong black cattle and Luxi cattle based on transcriptome analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21915.

Tang N, Wang SY, Jin-Wen QI, Yuan-Bing WU, Zhi-Qiong LI: Research progress on adiponectin regulating lipid metabolism. Chin J Animal Vet Sci. 2018,49(12):2550–7.

Bakhtiarizadeh MR, Moradi-Shahrbabak M, Ebrahimie E. Underlying functional genomics of fat deposition in adipose tissue. Gene. 2013;521(1):122–8.

Study of porcine adiponectin (ADIPOQ) gene and association of a missense mutation with EBVs for production and carcass traits in Italian Duroc heavy pigs. Livestock Science. 2009, 125(1):101–4.

Choi Y, Davis ME, Chung H. Effects of genetic variants in the promoter region of the bovine adiponectin (ADIPOQ) gene on marbling of Hanwoo beef cattle. Meat Sci. 2015;105:57–62.

Friedel S, Reichwald K, Scherag A, Brumm H, Wermter AK, Fries HR, Koberwitz K, Wabitsch M, Meitinger T, Platzer M, et al. Mutation screen and association studies in the diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase homolog 2 gene (DGAT2), a positional candidate gene for early onset obesity on chromosome 11q13. BMC Genet. 2007;8:17.

Yin Q, Yang H, Han X, Fan B, Liu B. Isolation, mapping, SNP detection and association with backfat traits of the porcine CTNNBL1 and DGAT2 genes. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(4):4485–90.

Tacken PJ, Teusink B, Jong MC, Harats D, Havekes LM, van Dijk KW, Hofker MH. LDL receptor deficiency unmasks altered VLDL triglyceride metabolism in VLDL receptor transgenic and knockout mice. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(12):2055–62.

Corominas J, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Puig-Oliveras A, Pérez-Montarelo D, Noguera JL, Folch JM, Ballester M. Polymorphism in the ELOVL6 gene is associated with a major QTL effect on fatty acid composition in pigs. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53687.

Laliotis GP, Bizelis I, Rogdakis E. Comparative approach of the de novo fatty acid synthesis (Lipogenesis) between ruminant and non ruminant mammalian species: from biochemical level to the main regulatory lipogenic genes. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(3):168–83.

da Costa AS, Pires VM, Fontes CM, Mestre Prates JA. Expression of genes controlling fat deposition in two genetically diverse beef cattle breeds fed high or low silage diets. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:118.

Tong X, Zhao F, Thompson CB. The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19(1):32–7.

Li S, Yang Z, Zhang H, Peng M, Ma H. (-)-Hydroxycitric acid influenced fat metabolism via modulating of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase expression in chicken embryos. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67(26):7336–47.

Li Q. Association Analysis of BMP2 and PDGF-D Polymorphisms with Tail Type in Sheep and Functional Verification at the Cellular Level Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences; 2019.

Chen SZ, Xu X, Ning LF, Jiang WY, Xing C, Tang QQ, Huang HY. miR-27 impairs the adipogenic lineage commitment via targeting lysyl oxidase. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(12):2445–53.

Huang H, Song TJ, Li X, Hu L, He Q, Liu M, Lane MD, Tang QQ. BMP signaling pathway is required for commitment of C3H10T1/2 pluripotent stem cells to the adipocyte lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(31):12670–5.

Mercer SW, Trayhurn P. Effect of high fat diets on energy balance and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue of lean and genetically obese ob/ob mice. J Nutr. 1987;117(12):2147–53.

Makwana K, Chodavarapu H, Morones N, Chi J, Barr W, Novinbakht E, Wang Y, Nguyen PT, Jovanovic P, Cohen P, et al. Sensory neurons expressing calcitonin gene-related peptide α regulate adaptive thermogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Mol Metab. 2021;45:101161.

Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Trayhurn P. Reduced lipogenesis in cafeteria-fed rats exhibiting diet-induced thermogenesis. Biosci Rep. 1983;3(3):217–24.

Wanders RJ, Ruiter JP. L IJ, Waterham HR, Houten SM: The enzymology of mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation and its application to follow-up analysis of positive neonatal screening results. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(5):479–94.

Britton CH, Schultz RA, Zhang B, Esser V, Foster DW, McGarry JD. Human liver mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: characterization of its cDNA and chromosomal localization and partial analysis of the gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(6):1984–8.

Meyers K, López M, Ho J, Wills S, Rayalam S, Taval S. Lipocalin-2 deficiency may predispose to the progression of spontaneous age-related adiposity in mice. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14589.

Liu C, Lin JD. PGC-1 coactivators in the control of energy metabolism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2011;43(4):248–57.

Stachowiak M, Szczerbal I, Flisikowski K. Investigation of allele-specific expression of genes involved in adipogenesis and lipid metabolism suggests complex regulatory mechanisms of PPARGC1A expression in porcine fat tissues. BMC Genet. 2018;19(1):107.

Baillie RA, Takada R, Nakamura M, Clarke SD. Coordinate induction of peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase and UCP-3 by dietary fish oil: a mechanism for decreased body fat deposition. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1999;60(5–6):351–6.

Casana E, Jimenez V, Sacristan V, Muñoz S, Jambrina C, Rodó J, Garcia M, Mallol C, León X, Franckhauser S, et al. BMP7 overexpression in adipose tissue induces white adipogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity in ob/ob mice. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45(2):449–60.

Lee KY, Singh MK, Ussar S, Wetzel P, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Kispert A, Kahn CR. Tbx15 controls skeletal muscle fibre-type determination and muscle metabolism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8054.

Gao C, Langefeld CD, Ziegler JT, Taylor KD, Norris JM, Chen YI, Hellwege JN, Guo X, Allison MA, Speliotes EK, et al. Genome-Wide Study of Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipose Tissue Reveals Novel Sex-Specific Adiposity Loci in Mexican Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(1):202–12.

Chen Y, Chen Y, Shi C, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Li S, Li Y, Ye J, Yu C, Li Z, et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience. 2018;7(1):1–6.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–60.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9.

Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43(Database issue):D1049–1056.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Ishiguro-Watanabe M, Tanabe M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D545-d551.

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–d612.

Li Q, Lu Z, Jin M, Fei X, Quan K, Liu Y, Ma L, Chu M, Wang H, Wei C: Verification and analysis of sheep tail type-associated PDGF-D gene polymorphisms. Animals (Basel) 2020,10(1):89.

Jin M, Lu J, Fei X, Lu Z, Quan K, Liu Y, Chu M, Di R, Wei C, Wang H: Selection signatures analysis reveals genes associated with high-altitude adaptation in Tibetan goats from Nagqu, Tibet. Animals (Basel) 2020,10(9):1599.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-38).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization CW and MJ; methodology XF; software TL; validation MJ and XF; formal analysis XF; investigation ZL, MC, RD, XH and XW; resources ZL; writing—original draft preparation MJ and XF; writing—review and editing CW; visualization MJ; project administration CW; funding acquisition CW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from The Animal Research Ethics Committee of Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All experimental procedures involving sheep were approved and carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines set by the Ethics Committee of Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No: IAS-2020–82). The manuscript adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of animal experiments, and the study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Table S1.

The top 8 most significantly affected differentially expressed genes in Hu sheep and Tibetan sheep. Table S2. Primers used in this study for RT-qPCR.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, M., Fei, X., Li, T. et al. Transcriptome study digs out BMP2 involved in adipogenesis in sheep tails. BMC Genomics 23, 457 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08657-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08657-8