Abstract

Background

In addition to human and animal diseases, bacteria of the genus Burkholderia can cause plant diseases. The representative species of rice-pathogenic Burkholderia are Burkholderia glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii, which primarily cause grain rot, sheath rot, and seedling blight, respectively, resulting in severe reductions in rice production. Though Burkholderia rice pathogens cause problems in rice-growing countries, comprehensive studies of these rice-pathogenic species aiming to control Burkholderia-mediated diseases are only in the early stages.

Results

We first sequenced the complete genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T. Second, we conducted comparative analysis of the newly sequenced B. plantarii ATCC 43733T genome with eleven complete or draft genomes of B. glumae and B. gladioli strains. Furthermore, we compared the genome of three rice Burkholderia pathogens with those of other Burkholderia species such as those found in environmental habitats and those known as animal/human pathogens. These B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii strains have unique genes involved in toxoflavin or tropolone toxin production and the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-mediated bacterial immune system. Although the genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T has many common features with those of B. glumae and B. gladioli, this B. plantarii strain has several unique features, including quorum sensing and CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) systems.

Conclusions

The complete genome sequence of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and publicly available genomes of B. glumae BGR1 and B. gladioli BSR3 enabled comprehensive comparative genome analyses among three rice-pathogenic Burkholderia species responsible for tissue rotting and seedling blight. Our results suggest that B. glumae has evolved rapidly, or has undergone rapid genome rearrangements or deletions, in response to the hosts. It also, clarifies the unique features of rice pathogenic Burkholderia species relative to other animal and human Burkholderia species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Burkholderia contains over 40 species, which occupy diverse niches and are found in a range of environmental habitats, including soil and water, and even in the hospital setting. Burkholderia organisms act as pathogens, endophytes, and symbionts [1,2]. Although many members of the genus are plant pathogens and soil bacteria, the most comprehensive characterizations of Burkholderia species have been conducted on those organisms that are opportunistic human pathogens [3]. One of two major human-infectious Burkholderia groups comprises B. mallei and B. pseudomallei, the causative agents of glanders and melioidosis, respectively. The other major group of Burkholderia human pathogens is B. cepacia complex bacteria, which are associated with severe infections in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Recently, increasing numbers of Burkholderia species have been reported as plant-associated bacteria.

Burkholderia species can be free-living in the plant rhizosphere, or can reside within plants as endophytes or symbionts. Some Burkholderia strains are known to aid plants by enhancing disease resistance, improving nitrogen fixation, and enabling adaption to environmental stresses [4-6]. However, there is little information regarding plant-pathogenic (phytopathogenic) Burkholderia species, with the exception of B. glumae. B. glumae causes grain rot in rice, and is used as a model system of quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms in gram-negative phytopathogenic bacteria [7-10]. Two other important phytopathogenic Burkholderia species, B. gladioli and B. plantarii, are pathogenic to rice and are primarily responsible for sheath rot and seedling blight, respectively [11,12]. Under the right environmental conditions, these three pathogenic Burkholderia species can cause severe damage to rice crops in various developmental stages.

In addition to occupying remarkably diverse niches, the genomes of Burkholderia species range greatly in size, from ~3.75 to 11.29 Mbp. Among Burkholderia organisms, B. rhizoxinica (a bacterial endosymbiont of the fungus Rhizopus microsporus) harbors the smallest genome (~3.75 Mbp), and the soil bacterium B. terrae has the largest genome (~11.5 Mbp). The first Burkholderia rice pathogen to have its complete genome sequenced was B. glumae BGR1 [13], and the genome of B. gladioli BSR3 was subsequently sequenced [14]. The genomes of B. glumae and B. gladioli both consist of two chromosomes and four plasmids, with genome sizes of 7.09 Mbp and 9.05 Mbp, respectively. Recently, comparative genome analysis of two B. glumae strains from different geographic regions showed high degree of genomic variation [15] and genetic differences between B. glumae and B. gladioli were investigated by comparative analysis of their complete genomes, along with four draft genomes from these two species [16]. These differences can lead to identification of specific virulence factors among strains.

In the present study, we sequenced the genome of the rice-pathogenic B. plantarii ATCC 43733T strain in order to compare its genome organization with that of B. glumae BGR1 and B. gladioli BSR3, and identify common and unique genes amongst these three Burkholderia rice pathogens. In addition, we compared the genome of these Burkholderia rice pathogens with the complete or draft genomes of other Burkholderia species, such as those found in different environmental habitats and those that are known to be pathogenic to animals and humans. Our comparative genome analysis demonstrates close relationships between the three rice pathogens and rice resulting in unique features of rice pathogenic Burkholderia species relative to other animal and human Burkholderia species.

Results and discussion

Genome sequencing and comparison

For comparative genome investigations of rice-pathogenic Burkholderia strains causing grain rot, sheath rot, or seedling blight, we examined the complete genome sequences from strains of B. glumae [13], B. gladioli [14], and B. plantarii (sequenced in the present study), along with publicly available complete or draft genomes from nine other Burkholderia strains (Table 1). The genomes ranged 4.9–9.0 Mbp in size, with a G + C content of 67.2–68.7%, and the number of predicted coded proteins was in the range of 4300–7400. Among the seven Burkholderia strains, the genome sizes were highly variable among and within species, although the G + C contents were very similar (Table 1). In the case of B. glumae, strain AU6208, harbored the smallest genome of ~4.9 Mbp, whereas strain BGR1 harbored the largest genome of ~7.2 Mbp. B. glumae, strain AU6208 was originally isolated from an infant patient with granulomatous disease and was pathogenic to rice. These findings suggest that B. glumae has evolved substantially, or has undergone rapid genome rearrangements or deletions, under different environments and hosts.

To better understand the interactions between rice-pathogenic Burkholderia species, comparative analysis was performed among the complete genome sequences of B. glumae BGR1, B. gladioli BSR3, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T (Table 2). Based on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 results, the genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T was 8.08 Mbp and consisted of two chromosomes and one plasmid. Chromosome 1 contained 4,140,040 bp (68.4% G + C content) and 3,456 predicted coding sequences (CDS), while chromosome 2 contained 3,743,649 bp (69.1% G + C content) and 2,862 CDS; the plasmid bgla_1p contained 197,362 bp (62.4% G + C content) and 145 CDS. Although B. glumae BGR1 and B. gladioli BSR3 both have a genome comprising two chromosomes and four plasmids, the genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T consists of two chromosomes and one plasmid. Multiple genome alignment for these three Burkholderia strains revealed a genome inversion in the middle of chromosomes 1 and 2 in B. glumae BGR1 when compared to the genomes of B. gladioli BSR3 and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T (Figure 1A and B). The genome organization of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T in the chromosome is much more similar to that of B. gladioli BSR3 than to that of B. glumae BGR1 (Figure 1A and B). MUMmer analysis and the size of the chromosome genome (Additional file 3: Figure S1 and Table 2) revealed a high number of genome deletions in chromosome 2 of B. glumae BGR1. Consistent with the observation of highly variable genome sizes in other B. glumae strains (Table 1), the genome of B. glumae appeared to be much more active than that of B. gladioli and B. plantarii.

Multiple genome alignment for three Burkholderia strains: Burkholderia glumae BGR1, B. gladioli BSR3, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T. The chromosome 1 (A) and chromosome 2 (B) sequences were aligned. The top, middle, and bottom sequences represent B. gladioli BSR3, B. plantarii ATCC 43733T, and B. glumae BGR1, respectively. Fine, colored lines represent rearrangements or inversions relative to the B. plantarii genome.

Genome comparison, pan-genome analysis, and core-genome analysis

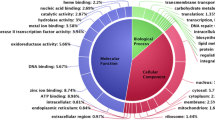

To obtain better understanding of the genomic characteristics of Burkholderia rice pathogens as compared to a wider variety of Burkholderia strains, we conducted pan-genome analysis of 106 Burkholderia genomes (listed in Additional file 1: Table S1), including those from animal/human pathogens and those isolated from environmental habitats. Overall, 78,782 orthologs were identified in all organisms, constituting the pan-genome of these 106 Burkholderia strains (Additional file 4: Figure S2). Among the 78,782 pan-genome genes, 587 genes were highly conserved among the 106 Burkholderia genomes, constituting the core genome. Interestingly, the omission of the B. glumae LMG 2196 and B. glumae AU6208 strain genomes increased the number of genes in the core genome dramatically, to 848 genes. Thus, these two B. glumae strains may have rapidly evolved under the given environmental conditions.

The new genome sequence of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T identified in the present study was combined with two full genomes of B. gladioli BSR3 and B. glumae BGR1, and four draft genomes in B. glumae and B. gladioli strains (Table 1) to identify a total of 12,758 orthologs that comprised the pan-genome of B. gladioli, B. glumae, and B. plantarii. Among these 12,758 genes, 1,908 genes were highly conserved and constituted the core genome of these seven Burkholderia strains (Figure 2). In addition, we identified 1,260 B. glumae-specific and 1,520 B. gladioli-specific genes. Among the seven B. glumae strains, the size of the strain-specific genome was ~340–840 genes (Figure 2), with the exception of B. glumae BGR1, which has only 233 strain-specific genes. As there were larger numbers of dispensable genes in B. glumae BGR1 than in other B. glumae strains, the B. glumae BGR1 genome could have stabilized or could be an original genome among these B. glumae strains.

Bacterial secretion system

Diverse metabolites and proteins can be secreted into the environment or into host cells through bacterial secretion systems [17,18]. Each bacterial system has its own unique function, including conjugation, and these systems sometimes share functions such as pathogenicity. The 12 Burkholderia strains within B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii species (listed in Table 1) have different numbers and types of secretion systems in their genomes. Genes involved in secretion-signal recognition particle (Sec-SRP) and twin arginine targeting (Tat) systems were highly conserved among all seven Burkholderia strains. The type III secretion system (T3SS) genes are also highly conserved in all 12 Burkholderia strains, except for deletion of sctQ, sctR, and sctS in the B. glumae LMG_2196 and AU6208 strains. Furthermore, with the exception of the partial sequence homology of hrpW in B. gladioli BRS3, the genes involved in the T3SS are nearly identical among B. glumae BGR1, B. gladioli BRS3, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T (Additioanl file 1: Table S2).

Evaluation of secretion system gene divergence revealed that all seven Burkholderia strains within the glumae group have one conserved type II secretion system (T2SS) on chromosome 1. However, B. plantarii ATCC 43733T has an additional T2SS in chromosome 2, while two B. gladioli strains have two additional partial T2SS. Among the seven Burkholderia strains within the glumae group, only B. glumae BGR1, B. glumae AU6208, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T have a type I secretion system (T1SS), whereas only B. gladioli BSR3 and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T have a type IV secretion system (T4SS) in their genomes. Thus, T1SS and T4SS show higher variability among the seven Burkholderia strains within the glumae group, as species-dependent total deletion of T1SS or T4SS was observed.

When compared to other genera, Burkholderia has a more diverse type VI secretion system (T6SS) with up to six T6SS gene clusters. Because the T6SS system can deliver bacterial proteins into both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, this secretion system is involved both in host pathogenesis and in anti-microbial mechanisms [19,20]. The T6SS apparatus structurally resembles an inverted bacteriophage tail that functions by injecting effector proteins directly into the cytosol of eukaryotic or bacterial cells. In particular, human- and animal-pathogenic B. pseudomallei and B. mallei have six T6SS gene clusters in their genome, four of which exist in both B. pseudomallei and B. mallei [21]. One T6SS is highly conserved among all 12 Burkholderia strains within the glumae group, which each harbor 2–4 T6SSs. Six T6SS groups can be classified in Burkholderia strains, based on the distribution of T6SS (Additional file 2: Table S3). T6SS_group1 was conserved in all genome-sequenced Burkholderia strains except for B. xenovorans, and was highly conserved among the seven Burkholderia strains within the glumae group. T6SS_group4 and T6SS_group5 were more specific to B. glumae or B. plantarii species: T6SS_group4 was only conserved among B. glumae and B. ambifaria; T6SS_group5 was only conserved among B. glumae and B. plantarii; and T6SS_group6 was only conserved among B. glumae, B. graminis, and B. plantarii. Different numbers of T6SS and unique T6SS in each species or strain indicate that T6SS could contribute to various inter-species interactions, including pathogen-host interactions and interactions with other microbes in the Burkholderia genus.

QS systems

Bacterial QS is a form of cell-to-cell communication that uses chemical signaling between bacterial cells to regulate biological processes in response to environmental clues [22]. N-acylhomoserine lactone (AHL), the best known QS chemical signal, plays a key role in the regulatory circuit composed of a signal producer designated LuxI and a cognate receptor-regulatory protein designated LuxR [23]. Burkholderia glumae BGR1 QS uses a TofI-TofR circuit, similar to the LuxI-LuxR circuit, to regulate toxoflavin biosynthesis, flagella regulation, and detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8-10]. Remarkably, B. glumae BGR1 QS protects stationary-phase cells from self-intoxication by altering cellular metabolism through the production of oxalate [24].

In this study, we surveyed AHL synthase and regulator in the genomes of 12 strains within B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii species (listed in Table 1). Overall, 16 paired AHL synthase-regulator circuits were identified in 12 strains (Table 3). One paired AHL synthase-regulator circuit displayed high sequence homology in all 12 strains except for B. gladioli NBRC 13700. An additional paired AHL synthase-regulator circuit was found in the genome of B. gladioli BSR3, residing in the polyketide synthesis operon of the plasmid. Furthermore, B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae PG1 had two additional paired AHL synthase-regulator circuits; one AHL circuit (bpln_2g10770-bpln_2g10790 and AJK 49063.1-AJK 49065.1) was located close to genes involved in the urea/branched-chain amino acid, and the other AHL circuit (bpln_2g04430-bpln_2g04440 and AJK 48489.1-AJK 48490.1) resided near the genes involved in thiopurine biosynthesis.

Without the AHL synthase pair, seven to twelve orphan AHL regulators existed in the genome of these 12 Burkholderia strains. Three orphan AHL regulators were highly conserved in all 12 Burkholderia strains. Twelve orphan AHL regulators were randomly distributed in the genome of B. plantarii ATCC. Overall, B. plantarii ATCC had the maximum number of AHL regulators among the 12 Burkholderia strains, suggesting that this strain synthesizes diverse auto-inducers and activates complicated regulatory systems in response to bacterial cell-to-cell communication.

Toxin production

Burkholderia toxin is a key virulence factor responsible for diseases in plants. Toxoflavin is the most well-known phytopathogenic Burkholderia toxin produced by B. glumae, and is a host-nonspecific phytotoxin that is a very effective electron carrier and generates ROS such as hydrogen [8,10]. Genes involved in toxin biosynthesis were surveyed in 12 strains within B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii species (listed in Table 1). Toxoflavin biosynthesis genes were distributed in all 12 Burkholderia strains except for B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae PG1 (Table 4). All B. glumae and B. gladioli strains harbored genes involved in the biosynthesis and transport of toxoflavin, except for a deletion of toxI in the genome of B. glumae AU6208. However, B. plantarii ATCC 43733T only had the toxJ gene, a regulator of toxin biosynthesis.

Instead of producing toxoflavin, B. plantarii is known to produce tropolone as a phytotoxin and as a virulence factor causing seedling blight. Rice seedlings exposed to tropolone typically exhibit symptoms similar to those of B. plantarii-mediated rice seedling blight [25]. When we surveyed all publicly available Burkholderia strain genomes, the genes involved in tropolone biosynthesis were only identified in the genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae PG1 (Additional file 1: Table S4). Interestingly, one paired AHL synthase-regulator circuit (bpln_1g07720-bpln_1g07790 and AJK 45325.1-AJK 45332.1) resided within the tropolone biosynthesis operon. This indicates that the regulation of tropolone biosynthesis may be dependent on bacterial cell-to-cell communication in a manner similar to that of the paired AHL circuit (bglu_2g14490-bpln_2g14470) in B. glumae BGR1, which regulates toxoflavin biosynthesis according to bacterial cell density [10], although these AHL circuit genes are not present in the toxoflavin biosynthesis operon.

Genes involved in rhizotoxin biosynthesis were also identified in the genome of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T. Rhizotoxin is an antimitotic agent with antitumor activity [26], isolated from a pathogenic plant fungus (Rhizopus microsporus). Rhizotoxin also causes rice seedling blight that results in the same symptoms as seedlings treated with tropolone. Genes involved in rhizotoxin biosynthesis have also been identified in several strains of bacteria, including Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae KACC10331 B. JYP251, B. phymatum, B. phenoliruptrix , and B. glumae PG1 (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Virulence-related enzymes

Genes encoding polygalacturonases, cellulases, lipases and proteases are major virulence factors in diverse pathogenic bacteria. These enzymes are related to the virulence and their regulation in B. glumae has been comprehensively summarized [7]. The characteristics, regulation, and virulence function of polygalacturonases in B. glumae was intensively investigated and pehA and pehB encoding two isoforms of polygalacturonases, have been discovered discovered [27]. The pehA locus was mainly distributed in B. glumae strains, whereas the pehB locus was detected in all B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii strains (Additional file 2: Table S7). The roles of lipases have been studied, not only in plant pathogenic strains but also in human pathogenic Burkholderia strains with respect to the virulence [28,29]. The gene encoding the lipase LipA was detected in all B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii strains except for B. glumae AU6208. These virulence-related enzymes in the 12 Burkholderia strains are summarized in Additional file 2: Table S7.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR-associated protein (Cas)

The CRISPR-Cas system is a bacterial immune system that protects bacteria from invading viruses and transferring plasmids [30,31]. Recent studies have indicated that the CRISPR-Cas system acts as a barrier to horizontal gene transfer and as a modulator of gene expression [32]. The CRISPR-Cas immune system blocks stable entry of foreign nucleic acids in three common steps: adaptation, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) biogenesis, and targeting [33,34]. During adaptation, viral or plasmid challenge stimulates the incorporation of short (24–48 nucleotide) invader-derived sequences between equally short DNA repeats found in the CRISPR locus [33,35]. These unique sequences, which are known as spacers, primarily match viruses and other mobile genetic elements [36].

We surveyed the CRISPR-Cas system in 106 Burkholderia genomes (listed in Additional file 1: Table S1). Remarkably, two B. plantarii ATCC 43733T , B. gladioli USD UG_CHAPALOTE, B. glumae PG1, and B. glumae 3252–8 strains have one CRISPR-Cas system. The other eight strains in the B. glumae and B. gladioli species have only the CRISPR motif without Cas proteins. However, no clear CRIPSR motif was identified in pathogenic-animal and human Burkholderia strains. The CRIPSR-Cas system in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T had an internal stop codon in the middle of the cas1 gene, leading to two separate Cas1; thus, the cas operon was composed of Cas1 (bpln_1g17440), Cas2 (bpln_1g17450), Cas3 (bpln_1g17460), Csy1 (bpln_1g17470), Csy2 (bpln_1g17480), Csy3 (bpln_1g17490), and Csy4 (bpln_1g17500) (Figure 3A). Among the 12 strains, B. gladioli, B. glumae, and B. plantarii species had four types of CRIPSR repeats, with the B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae 3252–8 strains sharing the common CRIPSR repeat (TTTCTAAGCTGCCTACACGGCAGCGAAC). Interestingly, B. glumae 3252–8 contained the cas operon between two CRIPSR repeats. Other five B. glumae strains had one or two CRISPR repeats without the cas operon (Figure 3B). These findings suggest that the cas operon was present in B. glumae, but was subsequently deleted in most B. glumae. Deletion events of the cas operon may have occurred in many Burkholderia strains; thus, we were only able to identify the cas operon in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T , B. glaidioli USD UG_CHAPALOTE, B. glumae PG1, and B. glumae 3252–8 from the genome sequences of over 100 Burkholderia strains.

We analyzed CRISPR targets, based on sequences of the CRISPR spacers in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae 3252–8, using Viroblast (http://indra.mullins.microbiol.washington.edu/viroblast/viroblast.php) or BLAST plasmid searches. The spacer/targeting sequences revealed diverse phage targets, including Burkholderia phages, other bacterial phages, and various types of plasmids (Additional file 2: Table S6). Interestingly, the CRISPR repeat (TTTCTAAGCTGCCTACACGGCAGCGAAC) common to both B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. glumae 3252–8 harbored the largest number of spacers. Specifically, there were 21 spacers in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and 12 spacers in B. glumae 3252–8. Three of 21 spacers in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T targeted several Burkholderia phages, including phage BcepC6B, phage KS14, and phage KL3, as well as plasmids of B. ambifaria MC40-6, B. cenocepacia, B. multivorans, and B. vietnamiensis with high sequence identities (Additional file 2: Table S6). However, 2 spacers among 12 in B. glumae 3252–8 targeted different types of bacteriophages, including Murine adenovirus 2 and Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL2338 with high sequence identities, but did not target bacterial plasmids.

Conclusions

The complete genome sequencing of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T performed in this study, and publicly available genomes of B. glumae BGR1 and B. gladioli BSR3, enabled comprehensive comparative genome analyses among three rice-pathogenic Burkholderia species responsible for tissue rotting and seedling blight. The genome organization and chromosome structure in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T are more similar to those of B. gladioli BSR3, which is consistent with the finding that B. plantarii ATCC 43733T and B. gladioli BSR3 are closely related based on 16S rRNA sequences. Genome analyses of interesting gene clusters such as secretion system genes, toxin production genes, bacterial QS genes, and CRISPR-mediated immune system genes indicated that B. plantarii ATCC 43733T has more diverse gene pairs in the QS-mediated AHL synthase-receptor circuit and in unique bacterial toxins such as tropolone and rhizotoxin. Interestingly, only the genomes of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T , B. glaidioli USD UG_CHAPALOTE, B. glumae PG1, and B. glumae 3252–8 harbored complete CRISPR-Cas systems, among all genome-sequenced for Burkholderia strains. Based on genome organization and toxin production, B. glumae PG1 was more closely related to B. plantarii ATCC 43733T than to the other B. glumae strains. Better knowledge of the variability and specificities of Burkholderia organisms could contribute to an understanding of their capacity to adapt to different environments, as well as their unique interactions with the host during pathogenesis.

Methods

Genome sequencing of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T

Whole-genome shotgun DNA sequencing of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T was conducted using an Illumina HiSeq 2000. In total, 200,106,179 paired-end reads were analyzed. The genomic shotgun sequence data were assembled with an ABySS [37] assembler, and contig ordering was confirmed by the 95,596 paired-end reads obtained from the 8-kb insert library using the Roche/454 pyrosequencing method on a Genome Sequencer FLX system. Gaps among contigs were closed by a combination of primer walking on gap-spanning clones and direct sequencing of combinatorial PCR products.

Gene annotation of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T

Coding genes and pseudogenes across the genome were predicted using Glimmer [38], GeneMarkHMM [39], and Prodigal [40], and were annotated by comparison with the NCBI-NR database [41]. Our annotation results were verified using Artemis [42].

Nucleotide sequence accession number of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T

The sequences of B. plantarii ATCC 43733T chromosome 1, chromosome 2, and plasmid genome have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers CP007212, CP007212, and CP007212, respectively.

Comparative and pan-genome analysis

A total of 111 Burkholderia genome sequences (with 37 complete and 74 draft genome sequences) were downloaded from NCBI. 16S ribosomal RNA sequences were used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) with MEGA6 software. Based on phylogenetic analysis, we divided Burkholderia species into a glumae group, cepacia group, mallei group, and outgroup (Additional file 5: Figure S5). We discarded five Burkholderia species, including B. rhizoxinica, because these species have higher genome variation owing to occupying ecological niches such as symbiosis. Overall, 12, 27, 49, and 18 species belonged to the glumae group, cepacia group, mallei group, and outgroup, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S1). For annotation of the unfinished genome and to make CDS prediction easier, all scaffolds for each strain were linked into a pseudochromosome according to the coordinates of ATCC_9150 with a piece of a random sequence. The scaffold linker (NNN NNC ATT CCA TTC ATT AAT TAA TTA ATG AAT GAA TGN NNN N) contains stop and start codons in all six frames, so it could prevent the protein-coding genes from extending from one scaffold to the next [43]. Pan-genome analysis was performed on a larger dataset of these 106 Burkholderia genomes using the GeneFamily method in the pan-genome analysis pipeline [44]. All proteins were filtered with the criteria of 50% coverage, 50% identity, and a 1.0 × e−10 e-value, and ortholog clusters were generated using MCL software [45].

CRISPR-Cas system

The CRISPRs Finder tool (http://crispr.u-psud.fr/Server/) was used to search for CRISPR direct repeats and spacers in the sequenced Burkholderia strains, which were then compared to JGI (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) analysis results. The CRISPR repeats were aligned in the genome and the sequences and locations of spacers were identified. We used Viroblast (http://indra.mullins.microbiol.washington.edu/viroblast/viroblast.php) and local BLAST analysis against NCBI plasmid genomes (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/Plasmids/) to identify the targets of the spacers.

Availability of supporting data

All supporting data are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- Bcc:

-

Burkholderia cepacia complex

- CRISPR-Cas:

-

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-CRISPR associated proteins

- CDS:

-

Coding sequences

- Sec-SRP:

-

Secretion-signal recognition particle

- Tat:

-

Twin arginine targeting

- T1SS:

-

Type I secretion system

- T2SS:

-

Type II secretion system

- T3SS:

-

Type III secretion system

- T4SS:

-

Type IV secretion system

- T6SS:

-

Type VI secretion system

- AHL:

-

N-acylhomoserine lactone

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species.

References

Compant S, Nowak J, Coenye T, Clément C, Ait Barka E. Diversity and occurrence of Burkholderia spp. in the natural environment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:607–26.

Vial L, Groleau M-C, Dekimpe V, Déziel E. Burkholderia diversity and versatility: an inventory of the extracellular products. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:1407–29.

Valvano MA, Keith KE, Cardona ST. Survival and persistence of opportunistic Burkholderia species in host cells. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:99–105.

Ait Barka E, Nowak J, Clément C. Enhancement of chilling resistance of inoculated grapevine plantlets with a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium, Burkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7246–52.

Compant S, Reiter B, Sessitsch A, Nowak J, Clément C, Ait Barka E. Endophytic colonization of Vitis vinifera L. by plant growth-promoting bacterium Burkholderia sp. strain PsJN. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1685–93.

Reis VM, Estrada-de los Santos P, Tenorio-Salgado S, Vogel J, Stoffels M, Guyon S, et al. Burkholderia tropica sp. nov., a novel nitrogen-fixing, plant-associated bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt 6):2155–62.

Ham JH, Melanson RA, Rush MC. Burkholderia glumae: next major pathogen of rice? Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12:329–39.

Chun H, Choi O, Goo E, Kim N, Kim H, Kang Y, et al. The quorum sensing-dependent gene katG of Burkholderia glumae is important for protection from visible light. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4152–7.

Kim J, Kang Y, Choi O, Jeong Y, Jeong J-E, Lim JY, et al. Regulation of polar flagellum genes is mediated by quorum sensing and FlhDC in Burkholderia glumae. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:165–79.

Kim J, Kim J-G, Kang Y, Jang JY, Jog GJ, Lim JY, et al. Quorum sensing and the LysR-type transcriptional activator ToxR regulate toxoflavin biosynthesis and transport in Burkholderia glumae. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:921–34.

Nandakumar R, Shahjahan AKM, Yuan XL, Dickstein ER, Groth DE, Clark CA, et al. Burkholderia glumae and B. gladioli cause bacterial panicle blight in rice in the southern united states. Plant Dis. 2009;93:896–905.

Solis R, Bertani I, Degrassi G, Devescovi G, Venturi V. Involvement of quorum sensing and RpoS in rice seedling blight caused by Burkholderia plantarii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;259:106–12.

Lim J, Lee T-H, Nahm BH, Choi YD, Kim M, Hwang I. Complete genome sequence of Burkholderia glumae BGR1. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3758–9.

Seo Y-S, Lim J, Choi B-S, Kim H, Goo E, Lee B, et al. Complete genome sequence of Burkholderia gladioli BSR3. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3149.

Francis F, Kim J, Ramaraj T, Farmer A, Rush MC, Ham JH. Comparative genomic analysis of two Burkholderia glumae strains from different geographic origins reveals a high degree of plasticity in genome structure associated with genomic islands. Mol Genet Genomics. 2013;288:195–203.

Fory PA, Triplett L, Ballen C, Abello JF, Duitama J, Aricapa MG, et al. Comparative analysis of two emerging rice seed bacterial pathogens. Phytopathology. 2014;104:436–44.

Hayes CS, Aoki SK, Low DA. Bacterial contact-dependent delivery systems. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:71–90.

Thanassi DG, Bliska JB, Christie PJ. Surface organelles assembled by secretion systems of Gram-negative bacteria: diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:1046–82.

Ho BT, Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:9–21.

Kapitein N, Mogk A. Deadly syringes: type VI secretion system activities in pathogenicity and interbacterial competition. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:52–8.

Burtnick MN, Brett PJ, Harding SV, Ngugi SA, Ribot WJ, Chantratita N, et al. The cluster 1 type VI secretion system is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1512–25.

Chen J, Xie J. Role and regulation of bacterial LuxR-like regulators. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2694–702.

Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:269–75.

Goo E, Majerczyk CD, An JH, Chandler JR, Seo Y-S, Ham H, et al. Bacterial quorum sensing, cooperativity, and anticipation of stationary-phase stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19775–80.

Azegami K, Nishiyama K, Watanabe Y, Suzuki T, Yoshida M. Tropolone as a root growth-inhibitor produced by a plant pathogenic Pseudomonas sp. causing seedling blight of rice. Ann Phytopathol Soc Japan. 1985;51:315–7.

Tsuruo T, Oh-hara T, Iida H, Tsukagoshi S, Sato Z, Matsuda I, et al. Rhizoxin, a macrocyclic lactone antibiotic, as a new antitumor agent against human and murine tumor cells and their vincristine-resistant sublines. Cancer Res. 1986;46:381–5.

Degrassi G, Devescovi G, Kim J, Hwang I, Venturi V. Identification, characterization and regulation of two secreted polygalacturonases of the emerging rice pathogen Burkholderia glumae. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65:251–62.

Devescovi G, Bigirimana J, Degrassi G, Cabrio L, LiPuma JJ, Kim J, et al. Involvement of a quorum-sensing-regulated lipase secreted by a clinical isolate of Burkholderia glumae in severe disease symptoms in rice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4950–8.

Mullen T, Markey K, Murphy P, McClean S, Callaghan M. Role of lipase in Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) invasion of lung epithelial cells. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:869–77.

Louwen R, Staals RHJ, Endtz HP, van Baarlen P, van der Oost J. The role of CRISPR-Cas systems in virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:74–88.

Koonin EV, Makarova KS. CRISPR-Cas: evolution of an RNA-based adaptive immunity system in prokaryotes. RNA Biol. 2013;10:679–86.

Hatoum-Aslan A, Marraffini LA. Impact of CRISPR immunity on the emergence and virulence of bacterial pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;17:82–90.

Gasiunas G, Sinkunas T, Siksnys V. Molecular mechanisms of CRISPR-mediated microbial immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:449–65.

Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–77.

Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–12.

Stern A, Keren L, Wurtzel O, Amitai G, Sorek R. Self-targeting by CRISPR: gene regulation or autoimmunity? Trends Genet. 2010;26:335–40.

Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, Birol I. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–23.

Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–41.

Lukashin AV, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–15.

Hyatt D, Chen G-L, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119.

Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D25–30.

Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–5.

Liang W, Zhao Y, Chen C, Cui X, Yu J, Xiao J, et al. Pan-genomic analysis provides insights into the genomic variation and evolution of Salmonella Paratyphi A. PLoS One. 2012;7, e45346.

Zhao Y, Wu J, Yang J, Sun S, Xiao J, Yu J. PGAP: pan-genomes analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:416–8.

Van Dongen S. A Cluster Algorithm for Graphs. PhD thesis, National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science in the Netherlands, 2000.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Rural Development Administration (No. PJ009774) and by the Creative Research Initiatives Program (2010–0018280) of the National Research Foundation of Korea and supported by a fund (B-1541785-2013-15-01) by the Research of Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, South Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

There are no ethical considerations relevant to this study, and the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YSS, JSM, and IH wrote the manuscript. SK, HC, and SMK performed the experiments. JYL, JP, HH, and YSS analyzed the genomic data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Genome information regarding 106 Burkholderia species used for pan-genome analysis. Table S2. Genes involved in Type III secretion among Burkholderia glumae BGR1, B. gladioli BSR3, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T. Table S4. Genes involved in tropolone biosynthesis in B. plantarii ATCC 43733T. Table S5. Genes involved in rhizotoxin biosynthesis among bacteria strains.

Additional file 2: Table S3.

The type VI secretion system (T6SS) in seven strains within B. glumae, B. gladioli, and B. plantarii species. Table S6. Lists of CRISPR target viruses or plasmids based on spacer sequences. Table S7. Distribution of genes encoding polygalacturonases, celluases, lipases, and proteases that are involved in virulence among Burkholderia strains.

Additional file 3: Figure S1.

MUMmer analysis of each chromosome between Burkholderia glumae BGR1, B. gladioli BSR3, and B. plantarii ATCC 43733T.

Additional file 4: Figure S2.

Pan-genome and core-genome analysis based on 106 genomes of Burkholderia strains (listed in Additional file 1: Table S1). The blue box, violet box, green box, and pink box represent the glumae group, cepacia group, mallei group, and outgroup, respectively. Each group is designated in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 5: Figure S3.

Additional file 5: Figure S3.

Phylogenetic tree of 106 Burkholderia species based on 16S rRNA sequences.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, YS., Lim, J.Y., Park, J. et al. Comparative genome analysis of rice-pathogenic Burkholderia provides insight into capacity to adapt to different environments and hosts. BMC Genomics 16, 349 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1558-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1558-5