Abstract

Background

Venomous organisms serve as wonderful systems to study the evolution and expression of genes that are directly associated with prey capture. To evaluate the relationship between venom gene expression and prey utilization, we examined these features among individuals of different ages of the venomous, worm-eating marine snail Conus ebraeus. We determined expression levels of six genes that encode venom components, used a DNA-based approach to evaluate the identity of prey items, and compared patterns of venom gene expression and dietary specialization.

Results

C. ebraeus exhibits two major shifts in diet with age—an initial transition from a relatively broad dietary breadth to a narrower one and then a return to a broader diet. Venom gene expression patterns also change with growth. All six venom genes are up-regulated in small individuals, down-regulated in medium-sized individuals, and then either up-regulated or continued to be down-regulated in members of the largest size class. Venom gene expression is not significantly different among individuals consuming different types of prey, but instead is coupled and slightly delayed with shifts in prey diversity.

Conclusion

These results imply that changes in gene expression contribute to intraspecific variation of venom composition and that gene expression patterns respond to changes in the diversity of food resources during different growth stages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Phenotypes for resource acquisition may evolve in response to changes in resource availability or utility. Gill rakers of alewives [1], drilling behavior of marine snails [2], venoms of snakes [3–5] and beaks of Darwin’s finches [6] all exhibit specific phenotypes that correspond to particular resources. But the genetic mechanisms underlying these phenotypic changes are mostly unknown. In addition to non-synonymous mutations, gene regulation also influences phenotypic changes. Expression of genes that contribute to the ability to consume particular resources is often regulated by characteristics of the resources [7, 8]. For example, for groups of mice that are fed with the same food items as those consumed by human and chimp, levels of differential expression in liver tissues of these mice are comparable to levels of differential expression between liver tissues of human and chimp [9]. This indicates that dietary changes exert more influence on gene expression than the inherent regulating mechanisms among species. To understand the genetic mechanisms underlying the dynamics of predator–prey interactions, it is essential to evaluate the effect of diets on expression of genes that are directly involved in resource utilization.

The developmental process, accompanied by drastic changes of phenotypes with age, represents an ideal case to explore the connection between gene expression and environmental cues [10]. Predatory marine snails of the family Conidae (‘cone snails’) exhibit particular dietary changes that are associated with increase in body size [11, 12], and many venom genes used for predation have already been well characterized [13, 14]. Leviten [11] suggested that diets of vermivorous Conus species shift from being trophic specialists as juveniles, to generalists as subadults, and then to specialists as adults. Characters associated with predation also exhibit vast changes during development. For example, radular teeth of Conus magus that are used to inject venom into prey, are morphologically distinct in juvenile and adult stages that specialize on polychaetes and fish respectively [15–17]. Cone snails use venom, a cocktail of numerous compounds including conotoxins, to capture prey and, for some species, to defend against predators [13, 18]. Conotoxins genes undergo extensive gene duplication and rapid evolution [19, 20], and their expression patterns are highly divergent among species [21–23]. Similar to the changes of radula teeth through development, the quantity and diversity of conotoxins may change with growth, but no prior study has tested this hypothesis.

To investigate patterns of changes of conotoxin gene expression and diet among individuals of different shell sizes, we chose Conus ebraeus, a vermivorous species, as our study organism. This species is abundant at numerous shallow water sites in the Indo-West Pacific and its diet has been studied previously [11, 12, 24]. We also have sequence alignments of several conotoxin genes from previous population genetic and molecular evolution studies of this species [22, 24–27], all of which facilitate the experimental design of this study.

We specifically addressed the following questions. Do conotoxin gene expression patterns differ among individuals of different ages? If so, how does expression change through time? Are some genes uniquely expressed only in particular stages? Do shifts in conotoxin gene expression patterns correspond with shifts in diet? If so, are the dietary shifts associated with changes in the types of prey or diversities of prey items? To answer these questions, we collected individuals from a single population at Guam, determined the identity of prey species based on microscopic examination of feces and a DNA-based approach, quantified conotoxin gene expression levels among individuals of different shell sizes, and evaluated the relationship between shifts in conotoxin gene expression and diet.

Methods

Specimens

We collected specimens of C. ebraeus at Pago Bay, Guam in May 2010. We measured shell lengths of each specimen upon collection. We placed individual specimens in separate cups that contained enough seawater to cover the animal, collected feces upon defecation, and preserved feces in the 95 % ethanol. Members of this species typically consume only one prey item every other night [28], and therefore each of our fecal samples usually contains the remains of a single prey individual [24]. After collecting feces we returned most samples back to their original collecting location at Pago Bay, and dissected 60 samples following the permit of Guam Department of Agriculture. We determined sexual maturity and sex of each specimen based on the presence/absence of a penis. We preserved venom ducts in RNAlater (Ambion, Inc.) and stored them at −20 °C prior to preparation of cDNA.

Identification of prey items

We examined feces from 243 individuals with microscopy to determine tentative identifications of prey items. Then we used a DNA-based approach described by Duda et al. [24] to further evaluate identifications. In brief, we obtained sequences of a region of the mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA gene from DNA extracts of feces, and aligned these with 16S rRNA sequences of polychaetes downloaded from GenBank (accession numbers shown in Fig. 1) in Se-Al 2.0 [29]. We obtained the relative positions of fecal sequences in neighbor-joining trees and from these results assigned fecal sequences to major taxonomic groups of Polychaeta (e.g., Eunicida, Nereididae and Syllidae). We selected the best substitution models with the Bayesian Information Criterion in jModelTest v0.1.1 [30] for alignments of 16S gene sequences for each of the taxonomic groups, and built Bayesian consensus phylogenies for each group separately with these models (10,000,000 generations, two runs, four chains, 25 % burn-in) in MrBayes v3.1.2 [31]. We ultimately determined the identity of prey species based on the sequence similarity and phylogenetic positions of fecal sequences with sequences of known or pre-defined polychaete species in these estimated species phylogenies.

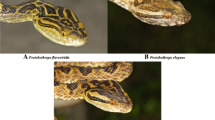

Phylogenies of 16S rRNA sequences of fecal samples of C. ebraeus and known polychaete species. Bayesian posterior probabilities are labeled at nodes of major clades. Sequences downloaded from GenBank are labeled with their respective accession numbers. Sequences obtained in this study are highlighted in bold. Putative prey species are labeled in grey next to the sequence names. a Phylogeny of species of the order Eunicida with GTR [76] + I + G model. b Phylogeny of species of the family Nereididae with GTR + G model. c Phylogeny of species of the family Syllidae with GTR + G model

Analysis of dietary data

Shell lengths provide an approximate estimate of ages of Conus individuals [11, 12]. To determine if individuals of different sizes show differences in prey selection, we performed one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of shell lengths of individuals consuming different prey species and higher taxonomic levels with the function lm in R v2.15.0 [32]. To identify patterns of transition in dietary composition, we built a heatmap of percentages of each prey species captured by individuals of a specific shell length bin with the heatmap.2 function in the gplots package [33]. We used Shannon-Weiner (H’) [34] and Gini-Simpson’s (S) [35] indices and average genetic distances (GD) to quantify levels of prey diversity in each size bin. The two parameters H’ and S were estimated with the function diversity in the package vegan [36]. To calculate GD, we estimated pairwise genetic distances of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA sequences of prey species with the Tamura-Nei [37] + G distance model and complete deletion of gaps in MEGA 5.05 [38], and computed the average genetic distances. We performed sliding-window analyses of H’, S and GD of dietary compositions with a window size of 5 mm in shell lengths.

We used F-statistics to evaluate patterns of genetic differentiation of dietary compositions among groups of individuals representing different size classes. We constructed these groups with a sliding window approach with a window size of 5 mm in shell lengths. We estimated pairwise Φ ST values (‘D ST’ values) as measures of the phylogenetic disparity of prey, of 16S rRNA sequences of prey items within each group/window in Arlequin 3.1 [39] with the Tamura-Nei distance model [37]. P-values were estimated from Monte Carlo simulations of 10,100 replicates. We built a heatmap of absolute D ST values along the gradient of shell lengths with the approach described above.

We defined ranges of shell lengths of small, medium and large individuals that correspond with inferred dietary transitions. This was achieved by defining the inflection points of increasing (or decreasing) trends in sliding window analyses of dietary diversities as well as the significance of the extent of genetic differentiation (as measured by D ST values) as boundaries of different size classes. We tested if the three size classes show differences in dietary composition by performing Fisher’s exact tests [40] with the fisher.test function. P-values were determined from results of 100,000 simulated datasets under the null hypothesis of no difference between groups.

Quantification of conotoxin gene expression

We extracted mRNA from venom ducts of 60 C. ebraeus individuals (with shell lengths ranging from 7 to 26 mm) and prepared complementary DNA (cDNA) following the approach described in Duda and Palumbi [19]. We examined six conotoxin genes that were identified from population studies of this species in the Indo-West Pacific [24, 27]: locus E1 (an O-superfamily locus that putatively encodes an ω-conotoxin), locus EA1 and EA4 (two A-superfamily loci that putatively encode α-conotoxins), locus ED4, ED8 and ED20 (three O-superfamily loci that putatively encode δ-conotoxins) (GenBank accession numbers JX177193, JX177106, JX177246, JX177272, JX177276, JX177278). These genes are expected to be single-copy, conform to Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium among populations; alleles of these genes of the Guam population have already been well characterized [27].

We used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to measure expression levels of the six conotoxin genes. The ‘carryover’ or contamination of genomic DNA in prepared cDNA can inflate expression levels of genes measured by qPCR. To avoid the interference of this ‘genomic DNA carryover’ in the quantification of gene expression, we specifically designed sets of primers that span known intron positions that should prevent any amplification from gDNA templates. We designed locus-specific reverse primers annealing to the toxin-coding region downstream to intron(s), and paired them with general forward primers that anneal within conserved regions upstream of the intron position(s) (i.e., within the signal or prepro region of the genes) (Additional file 1: Table S1). We tested specificity of these primer sets by amplifying and directly sequencing individuals with known genotypes.

We chose a β-tubulin gene as the endogenous control and estimated abundance of its gene transcripts with qPCR and primers specific for this locus (forward primer 5′ACAGCAGCTACTTTGTTGAATGGAT3′ and reverse primer 5′CAGTGTACCAATGGAGGAAAGCC3′). Expression levels of the β-tubulin gene, a ‘house-keeping’ gene, should be stable regardless of cells, tissue or developmental stages [41]. We added Tris-EDTA buffer to each cDNA preparation to a total volume of 175 μL and aliquoted an equal volume of cDNA samples for each qPCR run. We used SYBR Green chemistry to detect and quantify amplified products. All qPCR runs were performed on an ABI Prism 7500 machine at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry’s Molecular Biology Core Laboratory. To reduce the effect of noise associated with measurements, each round of qPCR was performed on three replicates for each individual; we used average results of the three replicates as estimates of expression levels. The amplification procedure included ten minutes of initial denaturing at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of amplification: denaturing at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 54 °C or 60 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 35 s in which fluorescent signals were collected. The annealing temperature of the β-tubulin locus and four conotoxin genes was 54 °C; for conotoxin loci E1 and ED4, the annealing temperature was 60 °C. We added a dissociation stage (95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 15 s for each sample) at the end of each run to evaluate the specificity of amplifications. The dissociation stage measures temperatures at which amplified products re-nature. Multiple temperatures of renaturation imply the presence of multiple unique DNA fragments and non-specific amplification. To ensure similarity in efficiency of primers of conotoxin genes with primers of the β-tubulin gene, we made 1/5 and 1/25 dilutions of cDNA samples of 12 individuals, and compared efficiencies of these primers following the approach described by Schmittgen and Livak [42].

We used the comparative CT method [42] to estimate expression levels of the six conotoxin genes relative to the endogenous house-keeping β-tubulin gene. CT values of some samples were labeled as ‘undetermined’ (the amplification did not reach the threshold by the last PCR cycle), and only very small amounts of target cDNA were amplified. To simplify the calculation, we converted ‘undetermined’ results to 40 (i.e., the last PCR cycle). We estimated ∆CT values of each conotoxin gene relative to the endogenous gene of each individual by subtracting average CT values of conotoxin genes among three replicates with that of the β-tubulin gene, and calculated relative expression levels of conotoxin genes with the formula \( {2}^{-\varDelta {\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{T}}} \).

Analysis of patterns of conotoxin gene expression

To normalize the conotoxin gene expression levels for statistical analyses, we used -∆CT as an approximation to the log transformation of expression levels of conotoxin genes relative to those of the β-tubulin gene \( \left( \log\;\left({2}^{-\varDelta {\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{T}}\ }\right)\right) \). We constructed a heatmap with C. ebraeus individuals as row variables, conotoxin loci as column variables, and absolute and scaled values of -∆CT as input. For samples that exhibited no amplification of the β-tubulin gene or conotoxin genes, we considered them to represent low quality cDNA preparations and eliminated them from subsequent analyses. We measured Euclidean distances of relative expression levels of conotoxin genes among samples with the function daisy in the package cluster [43]. Then we performed hierarchical clustering analyses with Wald’s method [44] with the function agnes in the package cluster to identify potential hierarchical structures of conotoxin gene expression.

Analysis of the association of shifts of diets and venom

We used boxplots of expression levels (−∆CT values) and one-way ANOVA to test if expression levels differ among samples consuming different prey species or higher taxonomic categories. We performed hierarchical clustering analysis with Wald’s method on this ‘reduced’ dataset, and tested if dietary composition differs between clusters with Fisher’s Exact Tests as described above.

To compare patterns of ontogenetic change of conotoxin gene expression and dietary composition, we centered and standardized results of sliding window analyses (the windows size of 5 mm) of -∆CT values of all conotoxin genes as well as dietary diversity estimators H’, S and GD. We viewed the increase of shell lengths as the progress of time/ages, and treated results of sliding-window analyses of expression levels of each conotoxin gene and estimates of dietary diversity of individuals of different shell lengths as time series. We tested if each time series of conotoxin gene expression is positively correlated with, plus a possible lead or lag of, the time series of dietary diversities using the cross-correlation ccf function, and verified the significance of results with a linear regression model (function lm) in R. The R scripts used in this study are available (from DC) upon request.

Results

Identification of prey species

Out of the possible fecal materials collected from 243 individuals of C. ebraeus, samples from 151 individuals contained hard parts of polychaetes that were identifiable from microscopic examination. Based on the morphological characteristics of these hard parts, we determined 86 samples to be of the family Nereididae, six of the family Syllidae, one of the family Terebellidae, and 49 of the order Eunicida, including 27 of the genus Palola. We obtained 16S rRNA sequences from DNA extracts of 54 fecal samples (Additional file 1: Table S2). Based on the similarities of these sequences with sequences of known annelid species and species defined in previous studies of diets of C. ebraeus [27, 45], we determined that the 54 fecal samples represent six Eunicida species (three Palola species), three Nereididae species and two Syllidae species (Fig. 1). Two species inferred from the phylogeny, ‘Palola A3’ and ‘Palola A9’, were previously characterized by Schulze [46]. Five inferred polychaete species, ‘Palola AX1’, ‘Eunicida 1’, ‘Eunicida 2’, ‘Eunicida 3’ and ‘Nereididae 1’, were found in dietary studies of C. ebraeus adults at Guam and American Samoa [27].

Age-related shift of diet

Nereididae and Palola species are consumed by a wide size range of C. ebraeus individuals (Fig. 2). The relatively rare species (‘Eunicida 1’, ‘Eunicida 2’, ‘Eunicida 3’, ‘Syllidae 1’ and ‘Syllidae 2’) are mostly consumed by small individuals. Different species and inferred genera of prey are targeted by predators of significantly different shell sizes (P-value = 0.011 for groups divided by prey species, with an average shell length range of 8-21 mm; P-value < 0.0001 for groups divided at prey genera, with an average shell length range of 9-19 mm; Fig. 2a-b). The average difference in shell lengths among prey types disappears when evaluated at the order level (Fig. 2c).

The diversity of prey differs among different size classes. Based on the inflection points of sliding window results of dietary diversity (Fig. 5a), we defined individuals with shell lengths smaller than 11 mm as ‘small’, those with shell lengths between 11 and 17 mm as ‘medium-sized’, and those larger than 17 mm in shell lengths as ‘large’. Small individuals exhibit the broadest dietary spectrum, medium-sized ones specialize mostly on Nereididae species, and large ones prey on both Nereididae and Palola species (Fig. 3a). Medium-sized individuals possess significantly different dietary composition in comparison to individuals of other size ranges, as illustrated by the sliding window analysis of phylogenetic disparity values D ST (Fig. 3b) and Fisher’s exact tests of prey species among the three size classes (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Heatmaps of dietary ontogeny of C. ebraeus individuals. a Heat map of frequencies of prey species consumed by C. ebraeus individuals of the same shell lengths. b Heat map of pairwise D ST values between size classes of sliding-window analyses (window size = 5 mm). P-values are estimated with simulations of 10,100 replicates, and significant results (P-value < 0.05) are labeled with asterisks in the cells

Age-related shift of conotoxin gene expression

We eliminated three individuals from analyses of conotoxin gene expression because these individuals yielded poor quality cDNA or included some failed reactions (Additional file 2). The remaining 57 individuals exhibit considerable variation in expression for the six conotoxin genes evaluated (Figs. 4 and 5). Expression levels are highest for small individuals and lowest in medium-sized ones (Figs. 4 and 5b). Hierarchical clustering analyses divided individuals into two major groups (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Cluster 1 contains individuals of a relatively even size distribution, whereas cluster 2 is composed exclusively of individuals at the two extremes of the size distribution (i.e., small and large individuals). Members of cluster 2 primarily exhibited higher levels of conotoxin gene expression than those of the cluster 1.

Patterns of ontogenetic shifts of dietary diversities and levels of conotoxin gene expression. Average levels of expression of six conotoxin genes and dietary diversities are calculated with a sliding window approach (with window size of 5 mm in shell lengths). a Plot of dietary variables versus average shell lengths. Shannon’s index (H’), Gini-Simpson’s index (S), and average genetic distances (GD). The Y-axis on the left represents S and GD, whereas the Y-axis on the right represents H’. b Plot of relative levels of expression of six conotoxin loci EA1, ED20, E1, EA4, ED4, and ED8 versus shell lengths. The expression levels are centered and standardized. c Cross-correlation of conotoxin gene expression levels and dietary diversities through increasing shell lengths, using conotoxin locus ED8 and dietary variable H’ as an example. Cross-correlations of all conotoxin genes and dietary variables are illustrated in Additional file 1: Figure S5. Y-axis: correlation coefficient of two series; X-axis: lag in shell lengths of H’ in comparison to conotoxin gene expression; blue dashed lines: 95 % confidence intervals. d Linear regression of lag of expression levels of locus ED8 with the dietary variable H’ by a time period equivalent to 2 mm in shell lengths. Regression analyses of expression levels of all conotoxin genes and dietary variables are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S6

Sliding window analyses revealed that average expression levels of conotoxin genes initially decrease and then increase with sizes of individuals (Figs. 4 and 5b). Expression levels of four genes ED4, ED8, E1 and EA4 are highest in small individuals and lowest in medium-sized individuals; expression levels increase in large individuals but do not reach the same levels as in small individuals (Fig. 5b). Average expression levels of loci EA1 and ED20 also decrease in medium-sized individuals, but do not show the same increasing pattern in large individuals as exhibited by the other genes (Fig. 5b).

Association between conotoxin gene expression and diet

Examination of conotoxin gene expression of 35 individuals whose prey items were also determined revealed no association between conotoxin gene expression levels and specific prey species. Expression levels of most conotoxin genes did not differ significantly among individuals consuming different prey taxa; the only exception is locus ED20 with a P-value = 0.006 (Additional file 1: Figure S2). No significant differences in conotoxin gene expression levels (including locus ED20) were detected among groups of individuals determined based on higher taxonomic levels of their prey (Additional file 1: Figures S3 and S4). The hierarchical clustering approach divided these individuals into two major clusters that exhibit no significant differences in prey utilization (P-value of the Fisher’s exact test is 0.270). Examination of the samples of the medium-sized and large groups, which only consumed Nereididae and Palola species, did not reveal any significant association between levels of conotoxin gene expression and dietary specialization (data not shown).

Patterns of variation in conotoxin gene expression and dietary diversity are similar in that both exhibit a trend of decrease and then increase with increases in shell lengths (Fig. 5a-b). However, the inflection points of the two time series are not coincident. Dietary changes lead changes in conotoxin gene expression by the amount of time equivalent to the growth time of one or two millimeters in shell length (Fig. 5c; Additional file 1: Figure S5). This pattern is confirmed by the significantly positive coefficients in cross-correlation and linear regression, tests applied to determine if dietary diversity of individuals is correlated with conotoxin gene expression levels of individuals one or two mm larger (Fig. 5c-d, Additional file 1: Figures S5 and S6). The only exception is conotoxin gene EA1; although changes in expression of this gene seem to lag changes in dietary diversity, no significant correlation was detected between the two variables (Additional file 1: Figure S5B).

Discussion

Through examination of fecal samples of over 200 C. ebraeus individuals and quantification of mRNA abundance of six conotoxin genes of 58 individuals of different sizes, we reconstructed time series of changes in dietary diversity and venom gene expression of C. ebraeus at Guam. The diversity of prey species targeted by these snails changes from high to low and then to high again with growth, while expression levels of conotoxin genes appear to be up-regulated in small individuals, down-regulated in medium-sized ones, and either go up or stay down in large individuals. We detected significant association between time series of conotoxin gene expression levels and sequential changes of dietary diversity, but the inflection points in conotoxin gene expression are delayed relative to dietary changes.

The observed patterns of changes in prey utilization with growth may be affected by three factors: competition and associated microhabitat differentiation, different body volume and energy efficiency of prey types, or minimization of predation risk. Intraspecific competition among congeners of different sizes, as well as interspecific competition at a particular growth stage, often reduce niche overlap and promote resource partitioning within an age-structured population [11, 47–50]. In addition, body size of predators determines the size of prey that is consumed [47, 48, 51, 52]. Cone snails engulf prey entirely, and therefore consuming prey that are larger than their handling capacity is costly [11]. Among prey items of C. ebraeus at Guam, members of the family Eunicidae typically exhibit the largest body sizes, followed by Nereididae and Syllidae [53], and these families of polychaetes are coincidently targeted by large, medium and small-sized cone snails as observed here. Moreover, prey handling time is usually shorter than searching time for many Conus species [11], and therefore small C. ebraeus may expand their dietary spectra to minimize their exposure to predation while searching for food.

Intrinsic factors associated with predation efficiency, such as the development of radular teeth and venom potency, may also affect a predator’s ability to subdue certain types of prey [15, 17]. The significantly positive association between conotoxin gene expression and dietary diversity implies that prey diversity may exert pressure on conotoxin gene transcription. Intraspecific heterogeneity in venom composition has been suggested to represent local adaptation to different prey utilizing patterns among populations of snakes [3, 54]. But other studies contend that differences in venom composition among populations of snakes are unlikely to be driven by selection that derives from differences in predator–prey relationships, because few prey can escape envenomation and develop heritable resistance [55–57]. We postulate that high concentration and diversity of venom components within a single population may be beneficial to capturing a more diverse array of prey. Here we assume that mRNA quantities of conotoxin genes are positively correlated with the quantities of peptides, which holds true for venom genes of snakes [58–60] but has not been tested in cone snails.

Associations between venom composition and diet are not exclusive to cone snails, but in other venomous organisms the age-related shift in venom composition is coupled with shift in prey specialization rather than prey diversity. For example, increased quantities of neurotoxins in neonates/juveniles snakes may enhance the success rate of immobilizing small prey, while increased levels of pre-digestive components in adults may be more efficient for handling large endothermic prey [5, 51, 54, 61–63]. Changes in nematocyst ratios and venom compositions among differently sized individuals of the Australian jellyfish Chironex fleckeri and Carukia barnesi are coincident with prey shifts from invertebrate-based diets to a vertebrate-based one [64, 65]. Unlike snakes and jellyfish, the strong coupling of conotoxin diversity and dietary diversity observed here has also been observed among species [20, 66] and among populations of the same species [27], and our study demonstrated that this mechanism is also applicable to individuals within a single population and through development.

Changes in conotoxin gene expression patterns exhibit a short delay relative to shifts in diet with growth, which suggests a potentially adaptive relationship between these two features. Environment-induced phenotypic and physiological variation often exhibits some delay relative to the environmental changes [67–70], and such a phenotypic change is advantageous when the delay is small [70]. The induced variation in phenotypes and physiology may result from transcription regulation [71–74], and the timing of gene regulation induced by environmental changes is different for genes affected. For example, increases in expression of heat-shock protein genes in yeasts occur almost immediately after heat exposure, but changes in expression of other genes occur some time after the exposure [72]. Therefore, conotoxin gene regulation may be facultatively induced by changes in dietary diversity. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that shifts in conotoxin gene expression represent a systematic process rather than one that is plastic with regards to changes in prey, nor the possibility that some of these conotoxin genes are used for defense rather than predation [18].

Moreover, the difference in timing of changes of conotoxin gene expression and diets is difficult to be quantified precisely. Frank [75] found that growth rates of C. miliaris exhibit a logarithmic relationship with shell lengths; during the first year of growth, shell length (up to 15 mm) is a linear approximation of growth rate. The lead of dietary shifts over changes of conotoxin gene expression reported here (the growth time of 1–2 mm in shell lengths) represents about 25 to 50 days of growth time if we assume growth rates of C. ebraeus and C. miliaris are similar. Nonetheless, increases in shell sizes of cone snail species can be abrupt and likely to be related to recent feeding bouts (personal communication by Alan Kohn). Therefore the difference in timing of dietary shifts and conotoxin gene regulation may be negligible.

Age-related variation of conotoxin gene expression and diet observed here can be confounded by several other factors. Because our sampling was performed at a specific time period, our data do not depict the seasonality in prey availability and prey choice. Moreover, we used a single gene, β-tubulin, as the endogenous control to quantify conotoxin gene expression under the assumption that expression levels of this gene are consistent among individuals [41]. If this assumption were not true, estimates of changes in conotoxin gene expression may be confounded by fluctuations in expression of the β-tubulin gene. Though levels of conotoxin gene expression are not significantly different among individuals that consumed different prey species, the limited number of individuals with known diets and conotoxin gene expression levels (i.e., N = 35) may reduce our power to detect an association, if any. In addition, age estimation of these individuals was solely based on shell lengths, variation of which within and among age classes may introduce noise in the real age-related patterns of changes in dietary specialization and venom gene expression. Experimental manipulation of predator–prey interactions and investigation of regulatory mechanisms of conotoxin genes may reveal more information about the evolution of venom gene expression in response to changes in prey specialization.

Conclusion

In summary, C. ebraeus at Guam exhibited high variability in conotoxin gene expression against increasing shell sizes. The pattern of variation of conotoxin gene expression is largely associated with, and delays relative to, changes in dietary diversity with age. Though we cannot disentangle the systematic changes in development and selection pressure from prey capture, expression levels of conotoxin genes among individuals of a single population are positively correlated with dietary diversity rather than with specific prey species, a novel discovery worthy of further investigation.

Online supplementary materials

Additional file 1: Tables S1-S3, Figures S1-S6 and Additional file 2 are available for download online.

Availability of supporting data

16S rRNA sequences of fecal samples are deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KM364562-KM364584.

Ethics

Collection of C. ebraeus samples has been conducted under the collection permits issued by the Department of Fishery and Wildlife Sciences at Guam, and the importation has been approved by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. All specimens have been deposited to the collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology's Mollusk Division.

References

Palkovacs EP, Post DM. Eco-evolutionary interactions between predators and prey: Can predator-induced changes to prey communities feed back to shape predator foraging traits? Evol Ecol Res. 2008;10:699–720.

Sanford E, Worth DJ. Local adaptation along a continuous coastline: prey recruitment drives differentiation in a predatory snail. Ecology. 2010;91(3):891–901.

Daltry JC, Wuster W, Thorpe RS. Diet and snake venom evolution. Nature. 1996;379(6565):537–40.

Gibbs HL, Sanz L, Chiucchi JE, Farrell TM, Calvete JJ. Proteomic analysis of ontogenetic and diet-related changes in venom composition of juvenile and adult Dusky Pigmy rattlesnakes (Sistrurus miliarius barbouri). J Proteomics. 2011;74(10):2169–79.

Mackessy SP, Sixberry NA, Heyborne WH, Fritts T. Venom of the Brown Treesnake, Boiga irregularis: Ontogenetic shifts and taxa-specific toxicity. Toxicon. 2006;47(5):537–48.

Schluter D, Grant PR. Ecological correlates of morphological evolution in a Darwin’s finch, Geospiza difficilis. Evolution. 1984;38(4):856–69.

Hodgins-Davis A, Townsend JP. Evolving gene expression: from G to E to G x E. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24(12):649–58.

Gibson G. The environmental contribution to gene expression profiles. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(8):575–81.

Somel M, Creely H, Franz H, Mueller U, Lachmann M, Khaitovich P, et al. Human and chimpanzee gene expression differences replicated in mice fed different diets. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1504.

Rohlfs RV, Harrigan P, Nielsen R. Modeling gene expression evolution with an extended Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process accounting for within-species variation. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:201.

Leviten PJ. The foraging strategy of vermivorous Conid gastropods. Ecol Monogr. 1976;46(2):157–78.

Kohn AJ, Nybakken JW. Ecology of Conus on Eastern Indian-Ocean fringing reefs - diversity of species and resource utilization. Mar Biol. 1975;29(3):211–34.

Olivera BM. Conus venom peptides: Reflections from the biology of clades and species. Ann Rev Ecol Syst. 2002;33:25–47.

Kaas Q, Yu R, Jin A-H, Dutertre S, Craik DJ. ConoServer: updated content, knowledge, and discovery tools in the conopeptide database. Nucl Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D325–30.

Nybakken J. Ontogenetic change in the Conus radula, its form, distribution among the radula types, and significance in systematics and ecology. Malacologia. 1990;32(1):35.

Nybakken J. Possible ontogenetic change in the radula of Conus patricius of the Eastern Pacific. Veliger. 1988;31:222–5.

Nybakken J, Perron F. Ontogenetic change in the radula of Conus magus (Gastropoda). Mar Biol. 1988;98(2):239–42.

Dutertre S, Jin A-H, Vetter I, Hamilton B, Sunagar K, Lavergne V, et al. Evolution of separate predation- and defence-evoked venoms in carnivorous cone snails. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3521.

Duda TF, Palumbi SR. Molecular genetics of ecological diversification: Duplication and rapid evolution of toxin genes of the venomous gastropod Conus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(12):6820–3.

Chang D, Duda TF. Extensive and continuous duplication facilitates rapid evolution and diversification of gene families. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(8):2019–29.

Duda TF, Remigio EA. Variation and evolution of toxin gene expression patterns of six closely related venomous marine snails. Mol Ecol. 2008;17(12):3018–32.

Duda TF, Palumbi SR. Gene expression and feeding ecology: evolution of piscivory in the venomous gastropod genus Conus. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2004;271(1544):1165–74.

Chang D, Duda T. Application of community phylogenetic approaches to understand gene expression: differential exploration of venom gene space in predatory marine gastropods. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14(1):123.

Duda TF, Chang D, Lewis BD, Lee TW. Geographic variation in venom allelic composition and diets of the widespread predatory marine gastropod Conus ebraeus. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6245.

Duda TF. Differentiation of venoms of predatory marine gastropods: Divergence of orthologous toxin genes of closely related Conus species with different dietary specializations. J Mol Evol. 2008;67(3):315–21.

Duda TF, Palumbi SR. Evolutionary diversification of multigene families: Allelic selection of toxins in predatory cone snails. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(9):1286–93.

Chang D, Olenzek AM, Duda TF. Effects of geographical heterogeneity in species interactions on the evolution of venom genes. Proc Royal Soc B. 2015;282(1805):20141984.

Kohn AJ. The ecology of Conus in Hawaii. Ecol Monogr. 1959;29(1):47–90.

Rambaut A. Se-Al sequence alignment editor. Version 2.0.a11. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2002.

Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(7):1253–6.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(8):754–5.

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012.

Warnes GR. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data, R package version 2.11.0. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots; 2012. Accessed 2015.

Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27:379–423. 623–656.

Jost L. Entropy and diversity. Oikos. 2006;113(2):363–75.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, et al. Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan; 2012. Accessed 2011-2014.

Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–26.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9.

Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform. 2005;1(EBO-1-Excoffier(Sc):47–50.

Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers (Biological Monographs and. Manuals No. V). 12th ed. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd; 1954.

Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. Human housekeeping genes, revisited. Trends Genet. 2013;29(10):569–74.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protocols. 2008;3(6):1101–8.

Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik K. cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. In., R package version 1.14.2 edn; 2012.

Struyf A, Hubert M, Rousseeuw P. Clustering in an object-oriented environment. J Stat Softw. 1997;1(4):1–30.

Duda TF, Lessios HA. Connectivity of populations within and between major biogeographic regions of the tropical Pacific in Conus ebraeus, a widespread marine gastropod. Coral Reefs. 2009;28(3):651–9.

Schulze A. Phylogeny and genetic diversity of Palolo Worms (Palola, Eunicidae) from the tropical North Pacific and the Caribbean. Biol Bull. 2006;210(1):25–37.

Werner EE, Gilliam JF. The ontogenetic niche and species interactions in size-structured populations. Ann Rev Ecol Systemat. 1984;15:393–425.

Polis GA. Age structure component of niche width and intraspecific resource partitioning: Can age groups function as ecological species? Am Nat. 1984;123(4):541–64.

Pianka EA. Niche overlap and diffuse competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71(5):2141–5.

Kohn AJ. Abundance, diversity, and resource use in an assemblage of Conus species in Enewetak Lagoon. Pacific Science. 1980;34(4):359–69.

Hayes WK. Ontogeny of striking, prey-handling and envenomation behavior of prairie rattlesnakes (Crotalus v. viridis). Toxicon. 1991;29(7):867–75.

Lowe CG, Wetherbee BM, Crow GL, Tester AL. Ontogenetic dietary shifts and feeding behavior of the tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, in Hawaiian waters. Env Biol Fish. 1996;47(2):203–11.

Leviten PJ. Resource partitioning by predatory gastropods of the Genus Conus on subtidal indo-pacific coral reefs: the significance of prey size. Ecology. 1978;59(3):614–31.

Barlow A, Pook CE, Harrison RA, Wüster W. Coevolution of diet and prey-specific venom activity supports the role of selection in snake venom evolution. Proc Royal Soc B: Bio Sci. 2009;276(1666):2443–9.

Williams V, White J, Schwaner TD, Sparrow A. Variation in venom proteins from isolated populations of tiger snakes (Notechis ater niger, N. scutatus) in South Australia. Toxicon. 1988;26(11):1067–75.

Sasa M. Diet and snake venom evolution: can local selection alone explain intraspecific venom variation? Toxicon. 1999;37(2):249–52.

Mebs D. Toxicity in animals. Trends in evolution? Toxicon. 2001;39(1):87–96.

Margres MJ, McGivern JJ, Wray KP, Seavy M, Calvin K, Rokyta DR. Linking the transcriptome and proteome to characterize the venom of the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus). J Proteomics. 2014;96:145–58.

Aird S, Watanabe Y, Villar-Briones A, Roy M, Terada K, Mikheyev A. Quantitative high-throughput profiling of snake venom gland transcriptomes and proteomes (Ovophis okinavensis and Protobothrops flavoviridis). BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):790.

Casewell NR, Wagstaff SC, Wüster W, Cook DAN, Bolton FMS, King SI, et al. Medically important differences in snake venom composition are dictated by distinct postgenomic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:9025.

Andrade DV, Abe AS, Santos MC. Is the venom related to diet and tail color during Bothrops moojeni ontogeny? J Herpetology. 1996;30(2):285–8.

Zelanis A, Tashima AK, Rocha MMT, Furtado MF, Camargo ACM, Ho PL, et al. Analysis of the ontogenetic variation in the venom proteome/peptidome of Bothrops jararaca reveals different strategies to deal with prey. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(5):2278–91.

Zelanis A, Tashima AK, Pinto AFM, Paes Leme AF, Stuginski DR, Furtado MF, et al. Bothrops jararaca venom proteome rearrangement upon neonate to adult transition. Proteomics. 2011;11(21):4218–28.

Carrette T, Alderslade P, Seymour J. Nematocyst ratio and prey in two Australian cubomedusans, Chironex fleckeri and Chiropsalmus sp. Toxicon. 2002;40(11):1547–51.

Underwood AH, Seymour JE. Venom ontogeny, diet and morphology in Carukia barnesi, a species of Australian box jellyfish that causes Irukandji syndrome. Toxicon. 2007;49(8):1073–82.

Phuong MA, Mahardika GN, Alfaro ME. Dietary breadth is positively correlated with venom complexity in cone snails. bioRxiv 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/028860.

Starck JM. Phenotypic flexibility of the avian gizzard: rapid, reversible and repeated changes of organ size in response to changes in dietary fibre content. J Evol Biol. 1999;202(22):3171–9.

Alstyne KLV. Herbivore grazing increases polyphenolic defenses in the intertidal brown alga Fucus distichus. Ecology. 1988;69(3):655–63.

Palumbi SR. Tactics of acclimation: morphological changes of sponges in an unpredictable environment. Science. 1984;225(4669):1478–80.

Padilla DK, Adolph SC. Plastic inducible morphologies are not always adaptive: the importance of time delays in a stochastic environment. Evol Ecol. 1996;10(1):105–17.

Lopez-Maury L, Marguerat S, Bahler J. Tuning gene expression to changing environments: from rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(8):583–93.

Richter K, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. The heat shock response: life on the verge of death. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):253–66.

Landry CR, Oh J, Hartl DL, Cavalieri D. Genome-wide scan reveals that genetic variation for transcriptional plasticity in yeast is biased towards multi-copy and dispensable genes. Gene. 2006;366(2):343–51.

Yampolsky LY, Glazko GV, Fry JD. Evolution of gene expression and expression plasticity in long-term experimental populations of Drosophila melanogaster maintained under constant and variable ethanol stress. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(17):4287–99.

Frank PW. Growth rates and longevity of some gastropod mollusks on the coral reef at Heron Island. Oecologia. 1969;2(2):232–50.

Tavaré S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. In: Miura RM, editor. Lectures on mathematics in the life sciences, vol. 17. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society; 1986. p. 57–86.

Acknowledgement

We thank Alex Kerr, Susanne Wilkins, Marielle Terbio, Carmen Kautz and Kirstie Goodman-Randall at University of Guam Marine Lab for their assistance with field collections. We acknowledge Jincong Tao in the Molecular Core Lab at University of Michigan School of Dentistry for his help with the Real-time PCR. We thank the Department of Fishery and Wildlife Sciences at Guam for issuing collection permits and the US Fish and Wildlife Service for processing the specimen importation from a US Territory. This project was funded by two Hinsdale-Walker Fellowships awarded to D.C. by the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DC and TFD designed the study. DC performed the field sample collection, the lab work, and analyzed the data. DC and TFD drafted the manuscript. Both authors gave final approval for publication.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supporting figures and tables. (DOCX 8211 kb)

Additional file 2:

Shell lengths of each sample and raw C values of the six conotoxin genes and the β-tubulin gene. (XLS 37 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, D., Duda, T.F. Age-related association of venom gene expression and diet of predatory gastropods. BMC Evol Biol 16, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0592-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0592-5