Abstract

Background

Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) comprises two subspecies, O. sativa subsp. indica and subsp. japonica, and the hybrids between them display strong heterosis. However, hybrid sterility (HS) limits practical use of the heterosis between these two subspecies. S5 is a major-effect locus controlling the HS of female gametes in rice, consisting of three closely-linked genes ORF3, ORF4 and ORF5 that act as a killer-protector system. The HS effects of S5 are inconsistent for different genetic backgrounds, indicating the existence of interacting genes within the genome.

Results

In the present study, the S5-interacting genes (SIG) and their effects on HS were analyzed by studying the hybrid progeny between an indica rice, Dular (DL) and a japonica rice, BalillaORF5+ (BLORF5+), with a transgenic ORF5+ allele. Four interacting quantitative trait loci (QTL): qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1, were genetically mapped. To analyze the effect of each interacting locus, four near-isogenic lines (NILs) were developed. The effect of each specific locus was investigated while the other three loci were kept DL homozygous (DL/DL). Of the four loci, qSIG3.1 was the SIG with the greatest effects in which the DL allele was completely dominant. Furthermore, the DL allele displayed incomplete dominance at qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1. qSIG3.1 will be the first choice for further fine-mapping.

Conclusions

Four S5-interacting QTL were identified by genetic mapping and the effect of each locus was analyzed using advanced backcrossed NILs. The present study will facilitate elucidation of the molecular mechanism of rice HS caused by S5. Additionally, it would provide the basis to explore the origin and differentiation of cultivated rice, having practical significance for inter-subspecific hybrid rice breeding programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Reproductive isolation provides the impetus for the formation and maintenance of species due to a reduction in gene flow between species or subspecies (Oka 1988). Depending on the developmental stage, reproductive isolation can be categorized as prezygotic and postzygotic ones (Seehausen et al. 2014). Prezygotic reproductive isolation prevents the formation of hybrid zygotes, while postzygotic reproductive isolation can lead to hybrid incompatibility (Ouyang and Zhang 2013). Inter-specific or inter-subspecific hybrid sterility (HS) is a common phenomenon causing postzygotic reproductive isolation (Ouyang and Zhang 2013). In addition to HS, postzygotic reproductive isolation can also result in hybrid lethality or weakness in F1 plants or their offspring (Ouyang and Zhang 2013; Fishman and Sweigart 2018).

As a staple food crop, sustainable production of high-yield rice is essential for global food security (Peng et al. 2008; Khush and Gupta 2013). Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) comprises two subspecies: indica and japonica, and hybrids of the two display strong heterosis (Yuan 1994; Zhang et al. 1996; Zhao et al. 1999). However, the value of inter-subspecific heterosis is somewhat limited due to HS (Ikehashi et al. 1994; Liu et al. 1996). Kato et al. (1928) demonstrated that the fertility of indica-japonica hybrid F1 plants ranged from 0% to 33%. Subsequently, a large number of HS loci were identified in rice (Ouyang et al. 2009). Of these, 11 HS genes have been cloned. The majority of cloned genes are related to the hybrid pollen sterility, such as Sa, DPL1/DPL2, S27/S28, Sc, DGS1/DGS2 and qHMS7 (Long et al. 2008; Mizuta et al. 2010; Yamagata et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2018). Several are related to hybrid embryo sac sterility, such as S5, hsa1, S7, and ESA1 (Yang et al. 2012; Kubo et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2016; Hou et al. 2019). Interestingly, S1 controls both male and female hybrid sterility (Xie et al. 2017; Koide et al. 2018; Xie et al. 2019).

A kind of special rice was called wide compatibility varieties (WCVs), whose hybrids display normal fertility when crossed with indica or japonica rice (Ikehashi and Araki 1984). Therefore, utilization of WCVs is considered a method of overcoming HS in rice. Dular, an indica rice from India, is a typical WCV (Liu et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 1997). The first wide compatibility gene (WCG), S5, has been identified as a major-effect locus controlling HS and wide compatibility (Ikehashi and Araki 1986; Liu et al. 1992; Liu et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998; Qiu et al. 2005; Song et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2008), which is also relevant to the evolutionary origin and differentiation of rice (Du et al. 2011; Ouyang et al. 2016; Mi et al. 2020). Initial research inferred that there are three alleles at the S5 locus: S5-i (indica rice), S5-j (japonica rice), and S5-n (WCVs). The fertility of hybrids containing S5-n/S5-i and S5-n/S5-j are normal, while those containing S5-i/S5-j are semi-sterile (Ikehashi and Araki 1986). A later study demonstrated that the S5 locus consists of three closely linked genes (ORF3, ORF4 and ORF5), which form a killer-protector system that regulates hybrid fertility (Yang et al. 2012). Both ORF4 and ORF5 have sporophytic mode of action, while ORF3 has gametophytic one. Typical japonica varieties carry ORF3−/ORF4+/ORF5- haplotype, while typical indica varieties carry ORF3+/ORF4−/ORF5+ haplotype (here “+” represents functional allele and “-” represents non-functional allele). In indica/japonica hybrids, ORF5+ and ORF4+ synergistically abort unguarded female gametes (carrying ORF3-, usually japonica gametes), while guarded female gametes (carrying ORF3+, usually indica gametes) is still live (Yang et al. 2012). Transcriptome analysis has shown that the ORF5+ protein might destroy the integrity of the cell wall, and signals are transmitted by transmembrane protein ORF4+ into the cell, resulting in severe endoplasmic reticulum stress, eventually leading to female gamete abortion (Yang et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2017). Nevertheless, during this process, ORF3+, an Hsp70 protein, can prevent endoplasmic reticulum stress and allow the production of fertile gametes (Yang et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2017).

It was observed that the effect of S5 varies depending upon the genetic background, indicating that unknown background gene(s) control HS by interacting with S5 (Yang 2012). The aim of the present study was to map those S5-interacting genes (SIGs), and develop near-isogenic lines (NILs) to analyze and verify the effects of each SIG, laying the foundation for genetic fine-mapping of SIG in the future.

Methods

Genetic Material

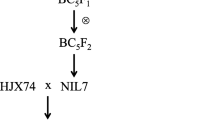

Balilla (abbreviated as BL, with S5 haplotype ORF3−/ORF4+/ORF5-) is a temperate japonica rice introduced from Italy. BLORF5+ was obtained by transforming the ORF5+ allele of the S5 locus into BL (Chen et al. 2008) (Fig. S1a). Positive transgenic plants BLORF5+ possess the suicidal S5 genotype (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5+, “+” representing the functional allele, “-” representing the non-functional allele), that displayed extremely low spikelet fertility (SF) (Fig. 1; Table 1). Dular (abbreviated as DL, with S5 haplotype ORF3−/ORF4−/ORF5n, “n” representing a non-functional allele) is an indica-type WCV introduced from India (Fig. 1; Table 1). F1 plants DL/BLORF5+ with the suicidal S5 genotype were derived from a cross between DL and BLORF5+ (Fig. 1; Table 1). A total of 173 individual plants (ORF5+ transgenic positive) of the F2 population were selected for QTL mapping. Other populations, such as BC3F3, BC4F6, and BC6F4 were developed by phenotypic selection and molecular marker-assisted selection, with BL as the recurrent parent. All plants were planted in the experimental fields of Guangxi University, Nanning, China.

Development of NILs to Analyze the Effect of each QTL

Before the related QTLs were determined, all transgenic plants with both suicidal S5 genotype and higher SF were selected to backcross with BL. The recurrent female parent BL has the S5 haplotype ORF3−/ORF4+/ORF5-, and the introduction of transgenic ORF5+ results in a suicidal S5 genotype (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5+). To isolate those plants carrying the suicidal S5 genotype (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5+), it was necessary to first identify the transgenic ORF5+ gene. Insertion and deletion (InDel) marker S5P50 (primer sequences detailed in Table S1), in the promoter region of ORF5+, has already been developed (Yang et al. 2012) (Fig. S1b). For further confirmation, histological staining was employed for reporter gene GUS (β-glucuronidase) to detect transgenic plants (Fig. S1c), which stained a blue color (Fig. S1c).

After the related QTLs had been determined, backcrossing could be facilitated by marker-assisted selection. Finally, selfing progeny of single-locus heterozygous (the other three loci were DL/DL homozygous, transgene ORF5+ was hemizygous) were used to analyze the effect of each QTL. For simplification, single-locus separating NILs for qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1 and qSIG12.1 were termed qSIG3.1-NIL, qSIG3.2-NIL, qSIG6.1-NIL and qSIG12.1-NIL, respectively (Table S2).

DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Total DNA was extracted from 1 g fresh rice leaves using cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) (Murray and Thompson 1980). Whole-genome InDel markers based on PCR were designed using rice genome sequence data (http://ricevarmap.ncpgr.cn/v2/). The names of markers defined their physical location on the respective chromosome. For example, marker C014115 was at 4115 kb on chromosome 1. Finally, 169 polymorphic InDel markers were selected for QTL mapping.

The InDel marker S5P50 (Yang et al. 2012) and GUS staining were used to identify transgenic ORF5+ plants. The positive plants were further genotyped using three primers: TL, TRB, and TR (Table S1) to detect copy numbers of foreign ORF5+ fragments. The three primers were designed using flank sequences of transgenic foreign ORF5+ fragment insertion. Additionally, the genotypes of BC6F2 generation plants were detected using a rice genome 6 K SNP microarray (China National Seed Group Co., Ltd).

Investigation of SF and Data Analysis

Three to five panicles were harvested from each individual plant to calculate the mean SF value. SF was measured as the proportion of well-developed fertile spikelets over the total number of spikelets. Mean values, standard deviations (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), and significance of differences were evaluated using SPSS v17.0 software (SPSS Inc., United States). The significance of differences was calculated using a t-test.

Construction of Genetic Linkage Map and QTL Mapping

The construction of genetic map and QTL mapping were conducted using IciMapping 4.0 software (www.isbreeding.net). After genotype data were imported into the software, markers were grouped only by anchor, ordered using the nnTwoOpt algorithm (nearest neighbor was used for tour construction, and two-opt was used for tour improvement) and rippled by the sum of adjacent recommendation frequencies (SARF) (Li et al. 2008). The Kosambi mapping function was used to estimate the genetic distance between markers. QTL were analyzed by inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) where LOD = 3.

Isolation of Transgenic ORF5+ Flanking Sequences and Development of a DNA Marker

The total genomic DNA of ORF5+ transgene-positive plants was cleaved using a single restriction endonuclease enzyme from multiple cloning sites of the ORF5+ transformation vector (pCAMBIA1301) (Chen et al. 2008). Foreign transgenic DNA fragments and the flanking genome DNA fragments then self-ligated into rings using T4 DNA ligase. Inverse PCR was performed to amplify the flanking sequence, using primer pair ULB2 and pCM13-L or XRB1, and pCM13-R, the sequences of which are detailed in Table S1. In the present study, clear bands were observed in the PCR products after digestion with BamH I or Xba I and amplification with ULB2 and pCM13-L. The PCR products were then sequenced and matched with the rice genome database to verify the location of the transgenic insertion.

For the next step, the three primers TL, TRB and TR, were designed to detect whether the transgenic insertion of ORF5+ was homozygous or hemizygous. Primers TL and TR were designed using the rice genome sequence and matched to the left and right side of the insertion position, respectively. The remaining primer, TRB was designed to match the components of the transgenic vector (Fig. S1d). If there was an ORF5+ transgenic insertion, a 170-bp fragment would be amplified using primers TRB and TR. Otherwise, a 200-bp fragment was amplified with primers TL and TR (Fig. S1e). Therefore, the genotypes of transgenic ORF5+ plants could easily be distinguished: one band at 200-bp for transgenic ORF5+ negative plants, two bands at 170-bp and 200-bp for the hemizygous ORF5+ transgenic plants, and only one band at 170-bp for the homozygous ORF5+ transgenic plants (Fig. S1e). The PCR products were examined using 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results

In the present study, QTL scanning and mapping of qSIG3.1 and qSIG5.1 were conducted using an F2 population. Due to the large effects of qSIG3.1 and qSIG5.1, other loci could not be identified in the F2 population. Surprisingly, a single qSIG3.1 locus cannot reflect its due effect in backcrossed progeny. Using marker-assisted backcrossing supplemented with phenotypic selection, we found qSIG3.2 and qSIG12.1 in the BC3F3 population via genome-wide molecular marker detection. In the BC6F2 generation, two plants did not show the expected SF. A rice genome 6 K SNP microarray was used to detect these two plants and found qSIG6.1. These QTL were detected by different methods in different populations.

Phenotypic Data of Parents and F1 Plants

The SF of the male parent BLORF5+ was < 5%, while that of female parent DL was > 80% (Fig. 1). The DL/BLORF5+ F1 plants were derived from a cross between DL and BLORF5+, whose SF was as high as 65% (Fig. 1), irrespective of its suicidal S5 genotype (Table 1). Since both BLORF5+ and DL/BLORF5+ possessed the same suicidal S5 genotype, the substantial SF differences between them indicated the existence of S5-interacting genes in the background genome.

Construction of Genetic Linkage Map and QTL Mapping in the F2 Population

In the F2 population of DL/BLORF5+, 173 individuals carrying the suicidal S5 genotype (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5+) were genotyped using 169 InDel markers. A genetic map was constructed with IciMapping 4.0 software, covering 1552.45 cM, with a mean distance of 9.19 cM between markers (Fig. S2). Two QTL qSIG3.1 and qSIG5.1 were mapped, using inclusive composite interval mapping with LOD ≥3. qSIG3.1 was located on chromosome 3, between markers C0326556 and C0328430 with a LOD of 3.18. The rate of phenotypic variation explained (PVE) by qSIG3.1 was 7.02% (Table 2). The additive (Add) and dominance (Dom) effects of qSIG3.1 were − 0.049 and 0.0763, respectively (Table 2). QTL qSIG5.1 was located on chromosome 5, between markers C051419 and C055412 with a LOD of 3.70 and PVE of 10.44% (Table 2). The Add and Dom of qSIG5.1 were − 0.038 and 0.0957, respectively (Table 2). In subsequent analysis, the location of qSIG3.1 was narrowed down to between markers C0327065 and C0328964 (Fig. 2) using several recombinants in BC4F3 (Fig. S3).

QTL qSIG5.1 Is the Insertion Site of ORF5+

In the F2 population, we observed severe segregation distortion at qSIG5.1. Of the 173 F2 individuals, only two were genotyped as DL/DL homozygous at the right flank marker C055412 (Table S3). Since all 173 F2 plants originated from the same transgenic ORF5+ plant, the foreign ORF5+ transgene should have been inserted into the same site of the BL genome. The closely linked markers of ORF5+ insertion site should be BL/BL homozygous or BL/DL heterozygous genotypes, with no DL/DL homozygotes. This deduction could well explain the serious segregation distortion at qSIG5.1. So we speculated that qSIG5.1 was in fact the insertion site of ORF5+.

In order to confirm this speculation, we isolated the flanking sequence of the insertion site of transgenic ORF5+. The foreign ORF5+ transgene was inserted between 4,621,102 bp and 4,621,103 bp on chromosome 5, just within the region of qSIG5.1. From the sequence information of the insertion position, three primers TL, TRB, and TR were designed to assess whether the transgenic ORF5+ was a hemizygote or homozygote (Fig. S1d).

Mapping qSIG3.2 and qSIG12.1 in the Backcrossed Progeny Using InDel Markers

In the backcrossed BC3 populations of qSIG3.1, an interesting observation was made. In a number of families, the SF of all the plants was less than 15%, irrespective of the qSIG3.1 genotype. In other families, the SF of plants with the same qSIG3.1 genotype varied widely. We speculated that other loci were affecting the SF of the plants. Two BC3F3 families with different SF were identified. The individuals with high SF (> 35%) were selected and genotyped with whole-genome InDel markers. Each plant carried two additional fragments from the DL variety (Fig. S4). One, named qSIG3.2, was narrowed down to be between markers C0317639 and C0323537, while a second, named qSIG12.1, was located between markers C124702 and C125855 (Fig. 2).

Mapping of qSIG6.1 in the Backcrossed Progeny Using an SNP Microarray

In a BC6F2 family, the genotypes of two plants, 18MR47–17 and 18MR47–19, were found to be similar. Both were BL/DL at qSIG3.2 and DL/DL at qSIG12.1, but 18MR47–17 and 18MR47–19 were BL/DL and DL/DL at qSIG3.1 respectively. Additional investigation revealed that the DL allele at qSIG3.1 was able to increase SF (see the section below about genetic effects analysis of qSIG3.1), and the DL allele at qSIG3.1 was completely dominant. Therefore, the SF of these two plants should be identical. However, the SF of 18MR47–17 was 44.43 ± 6.75%, and that of 18MR47–19 was only 19.79 ± 4.81% (Table 3), indicating the presence of other interacting loci.

To identify the new interacting loci, the genomes of these two individual plants were analyzed using a rice genome 6 K SNP microarray and the results were compared with their recurrent parent, BL. The microarray results indicated that 18MR47–17 and 18MR47–19 had different genotypes on chromosomes 6 and 12 (Fig. S5). 18MR47–17 which exhibited a higher SF was heterozygous BL/DL in both regions. On the other hand, 18MR47–19, with a lower SF, carried BL/BL and DL/DL on chromosomes 6 and 12 respectively. We speculated that the DL segment of chromosome 6 was able to increase the fertility of plant 18MR47–17. We termed this locus qSIG6.1. Based on the SNP information from the rice genome 6 K SNP microarray, a number of additional InDel markers were developed to verify the genotypes of 18MR47–17 and 18MR47–19 (Table S1). The location of QTL qSIG6.1 was finally identified as between markers C0625165 and C0626545 (Fig. 2).

Genetic Effects Analysis of qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, qSIG12.1, and ORF5+

To study the genetic effects of qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1, advanced NILs for each locus were developed, containing corresponding chromosomal segments from DL in the background of BL (Table S2). In BC6F4 NILs, when all four loci qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1 and qSIG12.1 were DL/DL homozygous, the SF of ORF5+ hemizygotes and homozygotes were 61.70 ± 1.00% and 17.47 ± 1.37% respectively (Fig. 3). The results suggested that the ORF5+ copy number greatly affected SF and only plants with hemizygous transgenic ORF5+ should be appropriate for conducting genetic effects analysis of qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1. When the genetic effect of individual QTL was analyzed, not only should the other three QTLs be DL homozygous (DL/DL), but also transgenic ORF5+ should be hemizygous.

Effect of transgene ORF5+ on spikelet fertility in BC6F4 families. a Spikelet fertility of homozygote (left) and hemizygote (right) of ORF5+ transgene. b Mean spikelet fertility value of homozygotes (left) and hemizygotes (right) of ORF5+ transgene. Data represent means ± SEM. Significant differences are indicated by **P < 0.01

For qSIG3.1-NIL, the SF of plants with genotypes qSIG3.1-BL/BL, qSIG3.1-BL/DL and qSIG3.1-DL/DL were 20.76 ± 0.76%, 59.57 ± 0.73% and 61.70 ± 1.00% respectively (Table 4). There were significant difference in SF between qSIG3.1-BL/BL and qSIG3.1-BL/DL, but no apparent SF difference between qSIG3.1-BL/DL and qSIG3.1-DL/DL. These results suggest that qSIG3.1 plays a significant role in SF, with the DL allele displaying complete dominance.

The SF of qSIG3.2-NIL plants with genotypes qSIG3.2-BL/BL, qSIG3.2-BL/DL and qSIG3.2-DL/DL were 38.76 ± 1.22%, 49.72 ± 0.89% and 56.76 ± 1.01% respectively (Table 4). The difference in SF between plants with different genotypes was significant. Nevertheless, the SF of plants with heterozygous genotype qSIG3.2-BL/DL fell between that of qSIG3.2-BL/BL and qSIG3.2-DL/DL, indicating that the DL allele at qSIG3.2 was incompletely dominant.

The SF of qSIG6.1-NIL plants with genotypes qSIG6.1-BL/BL, qSIG6.1-BL/DL and qSIG6.1-DL/DL were 45.46 ± 1.70%, 50.21 ± 1.50% and 56.11 ± 1.77% respectively (Table 4). There were minor differences in SF between each genotype. The SF of plants with the heterozygous genotype qSIG6.1-BL/DL also fell between that of qSIG6.1-BL/BL and qSIG6.1-DL/DL, indicating that the DL allele at qSIG6.1 displayed partial dominance.

The SF of qSIG12.1-NIL plants with genotypes qSIG12.1-BL/BL, qSIG12.1-BL/DL and qSIG12.1-DL/DL were 38.31 ± 2.56%, 59.50 ± 1.66% and 70.60 ± 1.05% respectively (Table 4). The SF of plants was significantly different between two different genotypes. The SF of plants with the heterozygous genotype qSIG12.1-BL/DL also fell between that of qSIG12.1-BL/BL and qSIG12.1-DL/DL, demonstrating that the DL allele at qSIG12.1 had incomplete dominance.

Discussion

Inter-specific or Inter-subspecific HS is caused by postzygotic reproductive isolation, which limits gene flow between species or subspecies. Therefore, HS genes are also known as speciation genes (Bateson 1909; Dobzhansky 1937; Muller 1942). The study of these genes in rice could help provide insight into the origin and differentiation of rice subspecies (Du et al. 2011; Ouyang et al. 2016).

Previous studies showed that the S5 locus on chromosome 6 originated from the Oryzeae tribe, most likely through Helitron transposition (Ouyang et al. 2016). The ancestral genotype of the three genes of the S5 locus is ORF3+/ORF4+/ORF5+, which mutated into ORF3+/ORF4−/ORF5+ and ORF3+/ORF4+/ORF5-. Finally, a trigenic reproductive isolation system was formed between indica and japonica rice (Ouyang et al. 2016). However, other genes are involved in the reproductive isolation caused by S5. The study of both S5 and its interacting genes will deepen our understanding of the evolutionary mechanism of rice.

It has been suggested that ORF4+ and ORF5+ together lead to an endoplasmic reticulum stress response, while ORF3+ prevents the stress response (Yang et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2017). However, the detailed molecular mechanism remains elusive. For example, it is not known what are the targets of ORF5+, how stress response is transmitted, or at which stage ORF3+ prevents a stress response. The study of SIG might fill this gap. Additionally, the results would also provide a valuable reference to the study of the molecular mechanism of other HS.

The cooperation between ORF5+ (killer) and ORF4+ (partner) of S5 results in the abortion of unguarded female gametes (carrying ORF3-), while female gametes carrying ORF3+ (protector) survive (Yang et al. 2012). The HS effect of S5 in the background of japonica rice was greater than that of indica rice (Yang 2012). The suicidal S5 haplotype has not been found in natural varieties (Yang et al. 2012). Therefore, the ORF5+ allele was transformed into japonica rice BL to form BLORF5+ with suicidal S5 genotype (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5+).

Although the SF of hybrid F1 DL/BLORF5+ was as high as 65% (Fig. 1), the plants heterozygous for qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1 and qSIG12.1 were sterile in the BC8F1 generation, with an SF of only 15.93% (Table S4). This difference in SF between F1 and BC8F1 probably originates from the difference in copy number of ORF4+. DL/BLORF5+ has a single copy of ORF4+ while BC8F1 has two copies of ORF4+. Yang et al. (2012) found a considerable dosage effect for both ORF4+ and ORF5+, without the presence of ORF3+. Both DL (ORF3-, ORF4-, and ORF5n) and BL (ORF3-, ORF4+, and ORF5-) carry the ORF3- allele, so all mapping populations used in the present research carry homozygous ORF3-, and the effect of S5 on SF was mainly dependent on copy numbers of ORF4+ and ORF5+. Similarly, since the copy number of ORF5+ greatly affected SF, it was preferable to keep hemizygous transgenic ORF5+ for genetic effect analysis (Fig. 3).

Four QTL qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1, were mapped in the present study. The genetic effect of the DL alleles differed among them: partially dominant at qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1, and qSIG12.1, while completely dominant at qSIG3.1. Of the QTL identified, qSIG3.1 displayed the greatest genetic effect, and is the most potential for gene cloning. Indeed, the DL allele could improve SF by approximately 40% in the BC6F4 qSIG3.1-NIL. We have constructed a fine-mapping population and expect to clone qSIG3.1 in the near future.

Conclusions

Four S5-interacting QTL, qSIG3.1, qSIG3.2, qSIG6.1 and qSIG12.1, were identified by genetic mapping. The effects of each QTL were analyzed using advanced backcross NIL. Of these, qSIG3.1 with potential breeding value exhibited the greatest genetic effect. The DL allele of qSIG3.1 is completely dominant. The effect of the other three loci was relatively small and their DL alleles were found to be partially dominant. The results of the present study would have laid the groundwork for the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of HS caused by S5 in rice.

Availability of Data and Materials

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/Additional Files.

Abbreviations

- HS:

-

Hybrid sterility

- SIG:

-

S5-interacting gene

- DL:

-

Dular

- BL:

-

Balilla

- SF:

-

Spikelet fertility

- NIL:

-

Near isogenic lines

- QTL:

-

Quantitative trait loci

- WCVs:

-

Wide compatibility varieties

- WCG:

-

Wide compatibility gene

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

- SEM:

-

Standard error of mean

- CTAB:

-

Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide

- GUS:

-

β-glucuronidase

- InDel:

-

Insert and deletion

- SARF:

-

Sum of adjacent recommendation frequencies

- ICIM:

-

Inclusive composite interval mapping

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- LOD:

-

Log odds score

- PVE:

-

Phenotypic variation explained by the marker

- Add:

-

Additive effect

- Dom:

-

Dominance effect

References

Bateson W (1909) Heredity and variation in modern lights. In: Seward A (ed) Darwin and modern science. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chen J, Ding J, Ouyang Y, Du H, Yang J, Cheng K, Zhao J, Qiu S, Zhang X, Yao J, Liu K, Wang L, Xu C, Li X, Xue Y, Xia M, Ji Q, Lu J, Xu M, Zhang Q (2008) A triallelic system of S5 is a major regulator of the reproductive barrier and compatibility of indica-japonica hybrids in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(32):11436–11441

Dobzhansky T (1937) Genetics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press. In: New York

Du H, Ouyang Y, Zhang C, Zhang Q (2011) Complex evolution of S5, a major reproductive barrier regulator, in the cultivated rice Oryza sativa and its wild relatives. New Phytol 191(1):275–287

Fishman L, Sweigart AL (2018) When two rights make a wrong: the evolutionary genetics of plant hybrid incompatibilities. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69:707–731

Hou J, Cao C, Ruan Y, Deng Y, Liu Y, Zhang K, Tan L, Zhu Z, Cai H, Liu F, Sun H, Gu P, Sun C, Fu Y (2019) ESA1 is involved in embryo sac abortion in interspecific hybrid progeny of rice. Plant Physiol 180(1):356–366

Ikehashi H, Araki H (1984) Varietal screening of compatibility types revealed in F1 fertility of distant crosses in rice. Jpn J Breed 34:304–313

Ikehashi H, Araki H (1986) Genetics of F1 sterility in remote crosses of rice. Rice Genet 1:119–130. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812814265_0011

Ikehashi H, Zou J, Huhn PM, Maruyama K (1994) Wide compatibility genes and indica-japonica heterosis in rice for temperate countries. Paper presented at the hybrid rice technology, IRRI, Manila, p 1994

Kato S, Kosaka H, Hara S (1928) On the affinity of rice varieties as shown by fertility of hybrid plants. Bull Sci Fac Agric Kyushu Univ 3:132–147

Khush GS, Gupta P (2013) Strategies for increasing the yield potential of cereals: case of rice as an example. Plant Breed 132(5):433–436

Koide Y, Ogino A, Yoshikawa T, Kitashima Y, Saito N, Kanaoka Y, Onishi K, Yoshitake Y, Tsukiyama T, Saito H, Teraishi M, Yamagata Y, Uemura A, Takagi H, Hayashi Y, Abe T, Fukuta Y, Okumoto Y, Kanazawa A (2018) Lineage-specific gene acquisition or loss is involved in interspecific hybrid sterility in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(9):E1955–E1962

Kubo T, Takashi T, Ashikari M, Yoshimura A, Kurata N (2016) Two tightly linked genes at the hsa1 locus cause both F1 and F2 hybrid sterility in rice. Mol Plant 9(2):221–232

Li H, Ribaut JM, Li Z, Wang J (2008) Inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) for digenic epistasis of quantitative traits in biparental populations. Theor Appl Genet 116(2):243–260

Liu A, Zhang Q, Li H (1992) Location of a gene for wide-compatibility in the RFLP linkage map. Rice Genet Newsl 9:134–136

Liu K, Wang J, Li H, Xu C, Liu A, Li X, Zhang Q (1997) A genome-wide analysis of wide compatibility in rice and the precise location of the S5 locus in the molecular map. Theor Appl Genet 95:809–814

Liu K, Zhou Z, Xu C, Zhang Q, Saghai Maroof MA (1996) An analysis of hybrid sterility in rice using a diallel cross of 21 parents involving indica, japonica and wide compatibility varieties. Euphytica 90(3):275–280

Long Y, Zhao L, Niu B, Su J, Wu H, Chen Y, Zhang Q, Guo J, Zhuang C, Mei M, Xia J, Wang L, Liu Y (2008) Hybrid male sterility in rice controlled by interaction between divergent alleles of two adjacent genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(48):18871–18876

Mi J, Li G, Xu C, Yang J, Yu H, Wang G, Li X, Xiao J, Song H, Zhang Q, Ouyang Y (2020) Artificial selection in domestication and breeding prevents speciation in rice. Mol Plant 13(4):650–657

Mizuta Y, Harushima Y, Kurata N (2010) Rice pollen hybrid incompatibility caused by reciprocal gene loss of duplicated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(47):20417–20422

Muller HJ (1942) Isolating mechanisms, evolution, and temperature. Biol Symp 6:71–125

Murray M, Thompson WF (1980) Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 8(19):4321–4326

Nguyen GN, Yamagata Y, Shigematsu Y, Watanabe M, Miyazaki Y, Doi K, Tashiro K, Kuhara S, Kanamori H, Wu J, Matsumoto T, Yasui H, Yoshimura A (2017) Duplication and loss of function of genes encoding RNA polymerase III subunit C4 causes hybrid incompatibility in rice. G3 7(8):2565–2575

Oka H (1988) Origin of cultivated rice. Japan Scientific Societies Press. In: Tokyo

Ouyang Y, Chen J, Ding J, Zhang Q (2009) Advances in the understanding of inter-subspecific hybrid sterility and wide-compatibility in rice. Chin Sci Bull 54:2332–2341

Ouyang Y, Li G, Mi J, Xu C, Du H, Zhang C, Xie W, Li X, Xiao J, Song H, Zhang Q (2016) Origination and establishment of a trigenic reproductive isolation system in rice. Mol Plant 9(11):1542–1545

Ouyang Y, Zhang Q (2013) Understanding reproductive isolation based on the rice model. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64(4):111–135

Peng S, Khush GS, Virk P, Tang Q, Zou Y (2008) Progress in ideotype breeding to increase rice yield potential. Field Crops Res 108(1):32–38

Qiu S, Liu K, Jiang J, Song X, Xu C, Li X, Zhang Q (2005) Delimitation of the rice wide compatibility gene S5n to a 40-kb DNA fragment. Theor Appl Genet 111(6):1080–1086

Seehausen O, Butlin RK, Keller I, Wagner CE, Boughman JW, Hohenlohe PA, Peichel CL, Saetre GP, Bank C, Brännström A (2014) Genomics and the origin of species. Nat Rev Genet 15(3):176–192

Shen R, Wang L, Liu X, Wu J, Jin W, Zhao X, Xie X, Zhu Q, Tang H, Li Q, Chen L, Liu Y-G (2017) Genomic structural variation-mediated allelic suppression causes hybrid male sterility in rice. Nat Commun 8(1):1310

Song X, Qiu S, Xu C, Li X, Zhang Q (2005) Genetic dissection of embryo sac fertility, pollen fertility, and their contributions to spikelet fertility of intersubspecific hybrids in rice. Theor Appl Genet 110(2):205–211

Wang J, Liu K, Xu C, Li X, Zhang Q (1998) The high level of wide-compatibility of variety 'Dular' has a complex genetic basis. Theor Appl Genet 97(3):407–412

Xie Y, Tang J, Xie X, Li X, Huang J, Fei Y, Han J, Chen S, Tang H, Zhao X, Tao D, Xu P, Liu Y-G, Chen L (2019) An asymmetric allelic interaction drives allele transmission bias in interspecific rice hybrids. Nat Commun 10:2501

Xie Y, Xu P, Huang J, Ma S, Xie X, Tao D, Chen L, Liu Y-G (2017) Interspecific hybrid sterility in rice is mediated by OgTPR1 at the S1 locus encoding a peptidase-like protein. Mol Plant 10:1137–1140

Yamagata Y, Yamamoto E, Aya K, Win KT, Doi K, Sobrizal IT, Kanamori H, Wu JZ, Matsumoto T, Matsuoka M, Ashikari M, Yoshimura A (2010) Mitochondrial gene in the nuclear genome induces reproductive barrier in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(4):1494–1499

Yang J (2012) Study on gene interaction involving hybrid sterility and wide compatibility in rice. Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, pp 101–102 https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDLAST2015&filename=1015531006.nh&v=Jifsx0fb3S6xxQtqacfN%25mmd2Bs6gwOLjPNs42NsouXU1NdRkyzlP%25mmd2FkmimlAaJqGW6vua.

Yang J, Zhao X, Cheng K, Du H, Ouyang Y, Chen J, Qiu S, Huang J, Jiang Y, Jiang L, Ding J, Wang J, Xu C, Li X, Zhang Q (2012) A killer-protector system regulates both hybrid sterility and segregation distortion in rice. Science 337:1336–1340

Yu X, Zhao Z, Zheng X, Zhou J, Kong W, Wang P, Bai W, Zheng H, Zhang H, Li J, Liu J, Wang Q, Zhang L, Liu K, Yu Y, Guo X, Wang J, Lin Q, Wu F, Wan J (2018) A selfish genetic element confers non-Mendelian inheritance in rice. Science 360:1130–1132

Yu Y, Zhao Z, Shi Y, Tian H, Liu L, Bian X, Xu Y, Zheng X, Gan L, Shen Y, Wang C, Yu X, Wang C, Zhang X, Guo X, Wang J, Ikehashi H, Jiang L, Wan J (2016) Hybrid sterility in rice (Oryza sativa L.) involves the tetratricopeptide repeat domain containing protein. Genetics 203(3):1439–1451

Yuan L (1994) Increasing yield potentials in rice by exploitation of heterosis. In: Virmani SS (ed) Hybrid Rice Technology: New Development and Future Prospects. IRRI. Manila, Philippines

Zhang Q, Liu K, Yang G, MAS M, Xu C, Zhou Z (1997) Molecular marker diversity and hybrid sterility in indica-japonica rice crosses. Theor Appl Genet 95(1):112–118

Zhang Q, Zhou Z, Yang G, Xu C, Liu K, MAS M (1996) Molecular marker heterozygosity and hybrid performance in indica and japonica rice. Theor Appl Genet 93(8):1218–1224

Zhao M, Li X, Yang J, Xu C, Hu R, Liu D, Zhang Q (1999) Relationship between molecular marker heterozygosity and hybrid performance in intra- and inter-subspecific crosses of rice. Plant Breed 118(2):139–144

Zhu Y, Yu Y, Cheng K, Ouyang Y, Wang J, Gong L, Zhang Q, Li X, Xiao J, Zhang Q (2017) Reproductive barriers in indica-japonica rice hybrids are uncovered by transcriptome analysis. Plant Physiol 174(3):1683–1696

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to Professor Qifa Zhang in Huazhong Agricultural University, China for providing transgenic BalillaORF5+.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060472, 31901486, 31471476), the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation of China (2018GXNSFDA050010, 2018GXNSFBA138022), Guangxi Science and Technology Development Program (AD19110145), the Scientific Research Foundation of Guangxi University (XTZ131548, XMPZ160942) and the State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources (SKLCUSA-a201916, SKLCUSA-a202004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY conceived and designed the experiments. JR performed the experiments and analyzed the data. XW and ZC provided assistance for data acquisition. JR drafted the manuscript. YF and JY analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Detection of ORF5+ transgenic plants. Figure S2. Genetic linkage map of the F2 population derived from the cross between Dular and BalillaORF5+. Figure S3. Additional mapping of qSIG3.1. Figure S4 Genotype of BC3F3 individuals with high SF. Figure S5. Rice genome 6 K-microarray analysis of 18MR47–17 and 18MR47–19. Table S1. Detailed information of primers. Table S2. Detailed information of NILs for each locus. Table S3. Genotypes of 173 F2 individual plants for two flank markers of qSIG5.1. Table S4. SF and genotypes of plants in different generations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, J., Wang, X., Cai, Z. et al. Genetic Analysis of S5-Interacting Genes Regulating Hybrid Sterility in Rice. Rice 14, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00452-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00452-x