Abstract

To date, electric fields have been widely used to control the magnetic properties of BiFeO3-based antiferromagnet/ferromagnet heterostructures through application of an exchange bias. To extend the applicability of exchange bias, however, an alternative mechanism to electric fields is required. Here, we report the photo-control of exchange bias in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films on an SrTiO3 substrate. Through an ex situ pulsed laser deposition technique, we successfully synthesized epitaxial BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films on SrTiO3 substrates. By measuring magnetoresistance under light illumination, we investigated the effect of light illumination on resistance, exchange bias, and coercive field in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films. After illumination of red and blue lights, the exchange bias was sharply reduced compared to that measured in the dark. With increasing light intensity, the exchange bias under red and blue lights initially decreased to zero and then appeared again. It is possible to reasonably explain these behaviors by considering photo-injection from SrTiO3 and the photo-conductivity of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3. This study may provide a fundamental understanding of the mechanism underlying photo-controlled exchange bias, which is significant for the development of new functional spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Within the last decade, the control of magnetic properties of materials using electric fields, and vice versa, has received great attention, as these effects may be utilized in a range of emerging spintronic device applications such as electric-field controlled tunneling magnetoresistance memory [1-4]. One of the strongest candidate materials for such functionality is BiFeO3 (BFO) because it exhibits coupling between ferroelectricity and antiferromagnetism at room temperature [5]. A promising application is the use of BFO as an antiferromagnetic layer for initiating exchange bias, a phenomenon that has been observed in antiferromagnetic/ferromagnetic multilayers [6]. Establishing an exchange bias in BFO/ferromagnet multilayers should facilitate the facile control of magnetism through electric fields [7-9].

There have been numerous studies of exchange bias in BFO-based multilayers, such as BFO/CoFe and BFO/CoFeB [7,10]. The exchange bias in BFO/ferromagnetic-metal heterostructures is strongly related to the ferroelectric domain walls of BFO, i.e., a 109° domain wall contributes to exchange bias, whereas 71° and 180° domain walls contribute to coercive field. On the other hand, the exchange bias in BFO/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 (BFO/LSMO) is related to the hybridization of interfacial Fe and Mn orbitals rather than the BFO domain walls [11]. We previously investigated exchange bias control in BFO/LSMO through illumination with light rather than by manipulating the applied electric field [12]. This effect was attributed to a reduction in the hole doping ratio of LSMO and weakened exchange coupling between Fe and Mn spins at the interface caused by photo-injected electrons from the SrTiO3 (STO) substrate. However, further investigation for the mechanism underlying photo-controlled exchange bias is needed to extend its scope.

In this paper, we investigated the wavelength and intensity dependence of exchange bias in BFO/LSMO thin films on STO substrates. Upon illumination with red and blue lights, resistance increased whereas the exchange bias and coercive field decreased. With the increase of light intensity, the exchange bias for red light becomes zero at 0.1 mW/cm2 and for blue light at 8.81 μW/cm2, i.e., much smaller intensity for blue light than red light. In contrast, the coercive field for both red and blue lights decreased with almost the same manner. The mechanism of photo-controlled exchange bias for BFO/LSMO thin films on STO substrates is discussed in conjunction with the effect of photo-injection from STO and photo-conductivity of LSMO for unpinned and pinned spins in BFO.

Methods

High-quality BFO/LSMO thin films were grown on an STO (001) substrate using pulsed laser deposition. A Q-switched 4ω Nd:YAG laser (266 nm, 5 Hz) was focused on BFO and LSMO ceramic targets with a fluence of approximately 1.5 J/cm2. Initially, we deposited an LSMO thin film at 750°C with an oxygen partial pressure (P O2) of 300 mTorr. A thin BFO film was then deposited ex situ on the LSMO/STO at 670°C and P O2 = 50 mTorr. Before BFO deposition, we blocked two regions of the LSMO using other STO substrates.

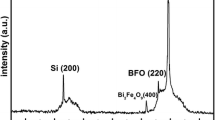

The crystalline structure of the BFO/LSMO thin film was characterized using high-resolution X-ray diffraction (HR-XRD) (Bruker, AXS D8 Discover; Bruker AXS, Inc., Madison, WI, USA) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with a Cs corrector (JEOL, 200 keV, JEM-2100 F; JEOL Ltd., Akishima-shi, Japan). The magnetic hysteresis curves of BFO/LSMO were obtained using the vibrating sample magnetometry functionality of a physical property measurement system (PPMS; Quantum Design, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For magnetoresistance measurement, we deposited Pt on the exposed LSMO regions and used a closed cycle cryostat (model 22, CTI-Cryogenics; Gardner Cryogenics, Bethlehem, PA, USA) equipped with an electromagnet (EM4-HVA, LakeShore Equipment Company, Carson, CA, USA). Thin films were illuminated through the optical window of a closed cycle cryostat with red (λ = 630 nm) and blue (λ = 460 nm) lights using light-emitting diodes (see the inset of Figure 1a).

Epitaxial growth of BiFeO 3 /La 2/3 Sr 1/3 MnO 3 thin film. (a) High-resolution X-ray diffraction (HR-XRD) and (b) cross section scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 (BFO/LSMO) thin films on SrTiO3 (STO) substrates. Spatial mapping of (c) Fe, (d) Mn, and (e) Ti elements. The inset of (a) shows a schematic illustration of the magnetoresistance measurement for the BFO/LSMO thin film under red and blue light illumination.

Results and discussion

Figure 1a, b shows the HR-XRD and cross section STEM results for BFO/LSMO thin films on STO substrates, respectively. From HR-XRD, it is apparent that the only a BFO (002) peak is observable near an STO (002). In addition, from STEM results, the lattice fringes for BFO, LSMO, and STO were clearly discernible without any noticeable lattice mismatches. Due to its thinness (approximately 5 nm), LSMO layer was only observable through STEM measurement. To further characterize the BFO/LSMO thin film on STO substrate, spatial mapping of the chemical elements Fe, Mn, and Ti is given in Figure 1c, d, e, respectively. While there are some ambiguities in our measurements, the majority of Fe, Mn, and Ti concentrations are observable at the top and bottom of the film and at the substrate, respectively. These results clearly suggest that BFO/LSMO multilayers should be epitaxially grown on an STO substrate using an ex situ pulsed laser deposition technique.

Figure 2a shows the magnetic hysteresis curves, M(H), for BFO/LSMO thin films at 25 K. We normalized the magnetic hysteresis curve to the saturated magnetization M S, i.e., M/M S. Before obtaining the M(H) curves for BFO/LSMO, we subtracted the contribution from diamagnetic STO substrates. One notable characteristic of the M(H) measurements is that the coercive field of BFO/LSMO was greatly enhanced compared to that of LSMO. In addition, the M(H) curves for BFO/LSMO shifted in the opposite direction to the applied magnetic field. It is worth noting that M(H) for LSMO did not shift in the direction of the applied magnetic field. These results clearly suggest that exchange bias is formed between antiferromagnet BFO and ferromagnet LSMO. To quantify the exchange bias, we defined the exchange bias field (H E) and coercive field (H C) as (H C1 + H C2)/2 and (H C1 – H C2)/2, respectively, where H C1 (H C2) represents the positive (negative) coercive field [6,13,14]. From the M(H) curve, we obtained H E = −24.5 Oe (+22.8 Oe) and H C = 425 Oe (420 Oe) for +1 T (−1 T) field cooling (FC).

Magnetization and magnetoresistance of BFO/LSMO thin film in the dark. Normalized (a) magnetization M/M S and (b) magnetoresistance R(H)/R(H X) curves of BFO/LSMO thin film after ±1 T field cooling (FC) at 25 K in under dark conditions. In (a), we show the normalized magnetization curve of LSMO thin film for comparison.

Interestingly, the coercive fields observed in the M(H) curve coincided with peak positions in the magnetoresistance curve R(H) [8,9], as shown in Figure 2b. We normalized the magnetoresistance to the value of resistance at which the two curves coincided at R(H X), i.e., R(H)/R(H X). Similar to the M(H) curve, the R(H) curves showed a shift in the opposite direction to the applied magnetic field. The values of H E and H C obtained from the R(H) curve (H E = −23 Oe and H C = 480 Oe for +1 T) were close to those obtained from the M(H) curve (H E = −24.5 Oe and H C = 425 Oe for +1 T). This implies that it is possible to investigate the exchange bias of BFO/LSMO multilayers by measuring the magnetoresistance R(H) instead of the magnetic hysteresis curve M(H).

After confirming the validity of magnetoresistance for the investigation of exchange bias, we illuminated the entire BFO/LSMO thin film surface with light at 25 K. Figure 3a, b shows the R(H) curves for BFO/LSMO thin films on an STO substrate after −1 T FC with light illumination at λ = 630 and 460 nm, respectively. For comparison, we superposed the R(H) curves obtained without any illumination. The R(H) curves under dark conditions, as shown in Figure 3a, b, are slightly different because we measured R(H) just before illumination of each wavelength after FC from 300 to 25 K to remove training effects [6].

Under illumination, the R(H) curves shifted upward and became symmetric, regardless of light wavelength, or intensity. However, detailed R(H) behaviors differed for each wavelength and intensity. For λ = 630 nm, exchange bias decreased with increasing intensity; H E was estimated to be approximately 16.0 and approximately 5 Oe for light intensities of 2.25 μW/cm2 and 1.83 mW/cm2, respectively. In contrast, for λ = 460 nm, exchange bias initially decreased and then increased with increasing intensity. Specifically, H E was estimated to be approximately 3 and 12 Oe for light intensities of 8.81 μW/cm2 and 2.73 mW/cm2, respectively.

To further investigate exchange bias, R(H) was measured under different light intensities. Figure 4a, b, c shows light intensity-dependent resistance R(H X), exchange bias field H E, and coercive field H C, respectively, for wavelengths of λ = 630 nm (red spheres) and 460 nm (blue spheres). For comparison, R(H X), H E, and H C without illumination are superposed (black spheres). As the intensity of light increases, the resistance slightly decreased under red light, while increasing for blue light (Figure 4a). Exchange bias decreased down to almost zero and then became nearly constant for red light and slightly increased for blue light (Figure 4b). In contrast, the coercive field for both red and blue light decreased.

Intensity and wavelength dependent resistance, exchange bias, and coercive field of BFO/LSMO thin film. Light intensity dependence of (a) resistance R(H X), (b) exchange bias field H E, and (c) coercive field H C for λ = 630 nm (red spheres) and 460 nm (blue spheres). In (a), (b), and (c), corresponding values under dark conditions (black spheres) are superposed for comparison.

Two effects were considered to explain these behaviors: photo-injection from STO and photo-conductivity of LSMO, both of which modify carrier concentrations in LSMO [15-17]. When photo-injection from STO occurs, the electron concentration in LSMO should increase. When photo-conductivity occurs in LMSO, however, the hole concentration in LSMO should increase.

In the case of photo-injection from STO, both λ = 630 and 460 nm lights can excite electrons due to the oxygen vacancy and transfer them into the LSMO layer. The band gap of STO is 3.27 eV (λ = 379 nm) [18], and hence, photo-injection should be more significant for λ = 460 nm than for 630 nm. In addition, the intensity dependence of photo-injection should be more significant for λ = 460 nm than for 630 nm. In the case of photo-conductivity of LSMO, irradiation at both λ = 630 and 460 nm should increase hole concentration. Considering the metallic property of LSMO [19], the photo-conductivity effect should be nearly identical at both wavelengths. In addition, the dependence of photo-conductivity on light intensity should be nearly identical for both λ = 460 and 630 nm. Holes are the majority carrier in LSMO [19]; as the light intensity increases, therefore, the resistance will decrease for λ = 630 nm and increase for λ = 460 nm, consistent with Figure 4a.

This change in carrier concentration should affect the magnetic properties of LSMO. According to recent theories [11,20,21], super-exchange ferromagnetic coupling occurs in interfacial Fe and Mn ions, while super-exchange antiferromagnetic coupling occurs in interfacial Mn and neighboring Mn ions at the BFO/LSMO interface. In addition, electron (hole) doping induces ferromagnetic (antiferromagentic) coupling between interfacial Mn and its neighboring Mn ions due to competition between double-exchange and super-exchange couplings. Thus, photo-injected electrons from STO should induce modulation of interfacial Mn spins to align parallel to neighboring Mn spins, while photoconductivity-induced holes in LSMO should induce interfacial Mn spins antiparallel to neighboring Mn spins. Therefore, exchange bias should decrease with increasing electron concentration, consistent with the fact that H E becomes nearly zero at approximately 0.1 mW/cm2 for red light and approximately 8.81 μW/cm2 for blue light (Figure 4b). Further increase of light intensity might result in the changes of compensated spins into uncompensated ones and/or pinned spins into unpinned ones due to the significantly increased electron and hole concentrations. While more investigation is required, such changes should result in the complicated behaviors of H E with respect to wavelength, shown in Figure 4b.

Coercive field decreases with increasing intensity, regardless of wavelength. Note that, exchange bias and coercive field are related to pinned and unpinned spins of antiferromagnet, respectively [6]. We can observe the independence of coercive field with respect to wavelength from the fact that unpinned spins of BFO should be easily rotatable with respect to the exchange-coupled spins of LSMO. The carrier concentration in LSMO may be different for red and blue lights, which results in different angle rotation for LSMO spins. Due to exchange coupling between Mn and Fe spins, unpinned spins of BFO should also be rotated through the same angle as in LSMO. When we rotate the spin of LSMO through the applied magnetic field, the unpinned spin in BFO rotates accordingly. Therefore, the coercive field should have no wavelength dependence. We can observe the dependence of coercive field with respect to intensity from the fact that an increase in intensity should result in a corresponding increase of rotated spins of LSMO. Through exchange coupling between Mn and Fe spins, the number of rotated unpinned spins of BFO should also increase. When we rotate the spin of LSMO through the applied magnetic field, the increased number of unpinned BFO spins should be easily rotated, due to decreased spin drag effects [6]. Therefore, the coercive field should decrease as light intensity increases, consistent with Figure 4c.

Conclusions

We reported intriguing photo-control of exchange bias in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films on SrTiO3 substrates grown using an ex situ pulsed laser deposition technique. Using high-resolution X-ray diffraction and scanning transmission electron microscopy, we confirmed that the film was epitaxially grown without any significant lattice mismatches. After confirming that positive and negative coercive fields were the same, using magnetic hysteresis and magnetoresistance measurements, we investigated the change in exchange bias under light illumination. Upon illumination with red and blue lights, exchange bias decreased with increasing resistance. With increasing light intensity, exchange bias decreased to nearly zero for red light at much higher intensity than for blue light. In addition, the exchange bias appeared again for further increase of light intensity. Based on the relationship between wavelength, photo-injection from SrTiO3, and photo-conductivity of La2/3Sr1/3MnO3, we can reasonably explain changes in resistance, exchange bias, and coercive field. Competitive accumulation of holes and electrons at the interface is the key factor in determining exchange coupling between Fe and Mn spins and initiating exchange bias.

References

Lottermoser T, Lonkai T, Amann U, Hohlwein D, Ihringer J, Fiebig M. Magnetic phase control by an electric field. Nature. 2004;430:541–4.

Kimura T, Goto T, Shintani H, Ishizaka K, Arima T, Tokura Y. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature. 2003;426:55–8.

Hur N, Park S, Sharma PA, Ahn JS, Guha S, Cheong S-W. Electric polarization reversal and memory in a multiferroic material induced by magnetic fields. Nature. 2004;429:392–5.

Allibe J, Fusil S, Bouzehouane K, Daumont C, Sando D, Jacquet E, et al. Room temperature electrical manipulation of giant magnetoresistance in spin valves exchange-biased with BiFeO3. Nano Lett. 2012;12:1141–5.

Catalan G, Scott JF. Physics and applications of bismuth ferrite. Adv Mater. 2009;24:2463–85.

Nogués J, Schuller IK. Exchange bias. J Magn Magn Mater. 1999;192:203–32.

Chu Y-H, Martin LW, Holcomb MB, Gajek M, Han S-J, He Q, et al. Electric-field control of local ferromagnetism using a magnetoelectric multiferroic. Nat Mater. 2008;7:478–82.

Wu SM, Cybart SA, Yu P, Rossell MD, Zhang JX, Ramesh R, et al. Reversible electric control of exchange bias in a multiferroic field-effect device. Nat Mater. 2010;9:756–61.

Wu SM, Cybart SA, Yi D, Parker JM, Ramesh R, Dynes RC. Full electric control of exchange bias. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110:067202.

Martin LW, Chu Y-H, Holcomb MB, Huijben M, Yu P, Han S-J, et al. Nanoscale control of exchange bias with BiFeO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2050–5.

Yu P, Lee J-S, Okamoto S, Rossell MD, Huijben M, Yang C-H, et al. Interface ferromagnetism and orbital reconstruction in BiFeO3-La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 heterostructures. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:027201.

Sung KD, Le TK, Park YA, Hur N, Jung JH. Photo-carrier control of exchange bias in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;104:252407.

Sung KD, Park YA, Seo MS, Jo Y, Hur N, Jung JH. Observation of intriguing exchange bias in BiFeO3 thin films. J Appl Phys. 2012;112:033915.

Sung KD, Park YA, Kim K-Y, Hur N, Jung JH. Uncompensated spins in exchange-biased BiFeO3/γ-Fe2O3 core/shell-like thin films. J Appl Phys. 2013;114:103902.

Katsu H, Tanaka H, Kawai T. Photocarrier injection effect on double exchange ferromagnetism in (La, Sr)MnO3/SrTiO3 heterostructure. Appl Phys Lett. 2000;76:3245.

Katsu H, Tanaka H, Kawai T. Dependence of carrier doping level on the photo control of (La, Sr)MnO3/SrTiO3 functional heterojunction. J Appl Phys. 2001;90:4578.

Cauro R, Gilabert A, Contour JP, Lyonnet R, Medici M-G, Grenet J-C, et al. Persistent and transient photoconductivity in oxygen-deficient La2/3Sr1/3MnO3-δ thin films. Phys Rev B. 2001;63:174423.

Capizzi M, Frova A. Optical gap of strontium titanate. Phys Rev Lett. 1970;25:1298.

Urushibara A, Moritomo Y, Arima T, Asamitsu A, Kido G, Tokura Y. Insulator-metal transition and giant magnetoresistance in La1-xSrxMnO3. Phys Rev B. 1995;51:14103.

Yi D, Liu J, Okamoto S, Jagannatha S, Chen Y-C, Yu P, et al. Tuning the competition between ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism in a half-doped manganite through magnetoelectric coupling. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;111:127601.

Vaz CAF, Hoffman J, Segal Y, Reiner JW, Grober RD, Zhang Z, et al. Origin of the magnetoelectric coupling effect in Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3/La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 multiferroic heterostructures. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:127202.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2013R1A2A2A01015734).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KDS and TKL prepared the thin films and performed the XRD, STEM, M(H), and R(H) measurements. KDS and JHJ designed the work and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, K.D., Lee, T.K. & Jung, J.H. Intriguing photo-control of exchange bias in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 thin films on SrTiO3 substrates. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 125 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-0824-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-0824-4