Abstract

Background

The presence of headache during the acute phase of COVID-19 could be associated with the innate response and the cytokine release. We aim to compare the cytokine and interleukin profile in hospitalized COVID-19 patients at the moment of admission with and without headache during the course of the disease.

Methods

An observational analytic study with a case control design was performed. Hospitalized patients from a tertiary hospital with confirmed COVID-19 disease were included. Patients were classified into the headache or the control group depending on whether they presented headache not better accounted for by another headache disorder other than acute headache attributed to systemic viral infection. Several demographic and clinical variables were studies in both groups. We determined the plasmatic levels of 45 different cytokines and interleukins from the first hospitalization plasma extraction in both groups.

Results

One hundred and four patients were included in the study, aged 67.4 (12.8), 43.3% female. Among them, 29 (27.9%) had headache. Patients with headache were younger (61.8 vs. 69.5 years, p = 0.005) and had higher frequency of fever (96.6 vs. 78.7%, p = 0.036) and anosmia (48.3% vs. 22.7%, p = 0.016). In the comparison of the crude median values of cytokines, many cytokines were different between both groups. In the comparison of the central and dispersion parameters between the two groups, GROa, IL-10, IL1RA, IL-21, IL-22 remained statistically significant. After adjusting the values for age, sex, baseline situation and COVID-19 severity, IL-10 remained statistically significant (3.3 vs. 2.2 ng/dL, p = 0.042), with a trend towards significance in IL-23 (11.9 vs. 8.6 ng/dL, p = 0.082) and PIGF1 (1621.8 vs. 110.6 ng/dL, p = 0.071).

Conclusions

The higher levels of IL-10 -an anti-inflammatory cytokine- found in our sample in patients with headache may be explained as a counteract of cytokine release, reflecting a more intense immune response in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Headache is one of the most frequent symptoms of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. In most cases it occurs within the first days after the onset of symptoms [2]. It is typically described as bilateral, frontal, pressing in quality and of severe intensity [3]. The profile of patients who present headache over the course of COVID-19 disease is unique, being associated with: i) demographic variables, as female sex, younger age, and prior history of headache [4] ii) a higher frequency of some clinical variables, as anosmia [5], myalgia, fever [4] and iii) a different laboratory profile, including a higher C-reactive protein, Interleukine-6 and D-dimer and a lower lymphocyte count [6].

The early onset [2], the unspecific phenotype [7], the similarities with headache associated with other systemic viral infections [8], and the coexistence with arthralgia, cough, lightheadedness and mialya [4] made some authors to suggest that it might be associated with the innate immune response and the cytokine release [4]. Cytokine storm has been described during COVID-19 infection, and prior studies have observed that patients with higher levels of selected cytokines and interleukins presented a more severe clinical presentation [9, 10]. Bearing in mind that headache is within the most common symptoms of COVID-19 (14,1%) [1], it seems plausible the presence of a specific headache and cytokine profile. However, this hypothesis has not been addressed yet. We present a pilot study in order to evaluate the cytokine and interleukin profile of COVID-19 patients with headache, compared with COVID-19 patients without headache. If this hypothesis is confirmed, new knowledge would support the molecular mechanisms underlying the headache related to COVID-19. These results could serve both to improve COVID-19 management and to describe new therapeutic targets that would have a direct impact on the quality of life of patients.

Methods

Design

This is an observational analytic study with a case-control design. The study population included patients with COVID-19 divided in two groups, depending on the presence or absence of headache. The study period was from March 8th to April 11th, 2020. The eligibility criteria have been extensively described in other studies [2, 4,5,6,7], and briefly included patients with confirmed COVID-19 disease that were hospitalized. The infection was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction test and/or serum antibody test. We excluded patients not admitted from the emergency department or those patients with unavailable electronic health records. The recruitment strategy was carried out by randomly enrolling one out of five patients from patients consecutively admitted to the hospital, since the first case diagnosed in our hospital Patients were classified into the headache or the control group depending on whether they presented headache not better accounted for by another headache disorder other than acute headache attributed to systemic viral infection [11]. The headache was evaluated by a neurologist with expertise on headache disorders. The study was done in the University Clinical Hospital of Valladolid, Spain. The Ethics Review Board approved the study (PI-20-1751, PI-20-1717).

Study objectives

The primary objective of the study was to describe the specific cytokine and interleukin profile of patients with headache during COVID-19.

Variables

We studied several demographic and clinical variables [2, 4,5,6,7] (supplementary materials). We analysed the clinical outcome, including the COVID-19 severity [12] (full definition in supplementary materials), and the need of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, ventilatory support, oxygen therapy and all-cause in-hospital mortality. As experimental parameters, we analysed the cytokine profile as summarized below.

Cytokine profile

The plasma samples were obtained from the antecubital vein, collected at the first extraction that was done in each patient during the hospitalization period. We use the 45-plex Human XL Cytokine Luminex Performance Panel (R&D) kit (Invitrogen, Thermofisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and using a Luminex™ MAGPIX™ Instrument System. In summary, it is a high resolution and sensitivity immunoassay based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method. With that technology, the concentration of the following cytokines was quantified: brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Eotaxin/CCL11, epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) alpha/chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1(CXCL1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), nerve growth factor (NGF) beta, leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), interferon (IFN) alpha, IFN gamma, interleukin (IL)-1 alpha, IL-1 beta, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8/CXCL8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, IL-18, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-27, IL-31, interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10)/ chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1)/chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein 1 (MIP-1) alpha/ (chemokine (C-C-motif) ligand 3(CCL3), regulated upon activation normal T Cell expressed and presumably secreted (RANTES)/ chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), stromal-cell derived factor 1 (SDF-1) alpha/CXCL12, tumoral necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, TNF beta/lymphotoxin alpha (LTA), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB, placental growth factor (PIGF-1), stem cell factor (SCF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and VEGF-D.

Statistical analysis

We present qualitative variables as frequency and percentage, and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) if the distribution was normal, or as median and inter-quartile range (IQR) if not. For hypothesis testing, we used Fisher’s Exact test, Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test.

We firstly analysed and compared baseline clinical and demographic variables in both groups (patients with headache and patients without headache).

Since this was a pilot study, the sample size was relatively small and there were many different analysed variables, we tried to validate the analysis by testing the analysis in terms of central tendency, dispersion and after adjusting for potential confounders. First, in order to compare the medians of the samples, since we expected a small sample with few outliers, we used Mood’s median test to compare the medians of headache patients and non-headache patients. Second, we tested the differences in shape and spread of the values by using the Mann-Whitney U tests. Third, we compared the parameters adjusting for covariates by using ANCOVA. The adjusted variables included age, sex, days since the onset of COVID-19 and severity of the disease.

We considered results as statistically significant if the p-value was < 0.05, however, given that this was a pilot study, we aimed to report also those variables with a trend towards signification (p < 0.1), since researchers might prioritize their study in future research projects. We did not estimate sample size in advance. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS v26 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY).

Results

One hundred and four patients were included in the study, aged 67.4 (12.8), 43.3% female. Among them, 29 (27.9%) had headache. Patients with headache were younger (61.8 vs. 69.5 years, p = 0.005) and had higher frequency of fever (96.6 vs. 78.7%, p = 0.036) and anosmia (48.3% vs. 22.7%, p = 0.016). We did not observe differences in other demographic variables, frequency of prior history conditions, clinical symptoms or variables related with the clinical outcome (Table 1).

Regarding the central tendency measures, in the comparison of the crude median values of cytokines, we observed that patients with headache had higher median values of GROa, IFN-gamma, IL-10, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17a, IL-21, IL-22, IL-27 and IL-6 (Table 2).

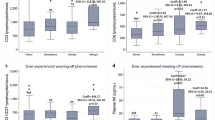

In regard to the central and dispersion of the parameters, in the comparison of the shape and spread between the two groups, GROa, IL-10, IL1RA, IL-21, IL-22 remained statistically significant, while there were trends towards signification (p < 0.1) in FGF-2, IFNg, IL12p70, IL-23, IL-27, IL31, IL-6, IL-9 and TNF-b (Table 3). After adjusting the values for age, sex, baseline situation and COVID-19 severity, only IL-10 remained statistically significant (3.3 vs. 2.2 ng/dL, p = 0.042) with a trend towards signification in IL-23 (11.9 vs. 8.6 ng/dL, p = 0.082) and PIGF1 (1621.8 vs. 110.6 ng/dL, p = 0.071) (Figs. 1, 2 and 3) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we compared, for the first time, the cytokine profile between patients with and without headache during COVID-19 infection. In this pilot study, we analysed 45 different cytokines and interleukins. The main finding of our study was that IL-10 levels were significantly higher in patients with headache while other interleukins, such as IL-23 and PIGF1, also showed a trend to be higher in this group.

Our results should be interpreted with caution. In ideal conditions, considering that COVID-19 is a dynamic disease, the analytic parameters should have been obtained in the same stage of disease, and after the same time since the onset of the clinical symptoms. However, in order to make this study reproducible, the samples were collected in the first extraction after the hospital admission. We tried to minimize this problem by statistically adjusting for days of evolution of the symptoms, but this adjustment subtracted statistical power to the study. Besides, this was an exploratory study and instead of testing a single hypothesis, a high number of different cytokines were studied.

Despite the cytokine storm has been hypothesized as one of the possible mechanisms underlying headache in COVID-19 patients [13], few previous studies had analysed the relationship between cytokines levels and headache. To date, only IL-6 levels have been studied in COVID-19 patients with and without headache, in retrospective studies with contradictory results [6, 14]. Studies addressing differences in other interleukins were still lacking in the literature.

Our findings could support the hypothesis of a cytokine mediated mechanism underlying headache in COVID-19. The relationship between cytokines and headache has been studied for a long time [15]. The external administration of different cytokines, such as TNF, INF alfa, INF beta, INF gamma or IL-2, causes headache in humans [16, 17]. In addition, several studies have found relationship between primary headaches and elevated levels of cytokines. Regarding migraine, although there are discrepancies in literature, probably as a consequence of different patterns of sample collection relative to the time of attack [18], elevated serum levels of TNF a, IL-1b, IL-6, GM-CSF and IL-10 have been found during attacks and in attack free intervals [19,20,21,22,23]. Tension type headache also have been associated with elevated levels of IL-6 or IL-8 [24, 25]. Finally, in the case of systemic infections, cytokine cascade is thought to be the primary mechanism of headache and other accompanied symptoms, as fatigue, anorexia or nausea [11, 26].

Several studies have suggested a main role of the cytokine storm in the evolution of COVID-19 illness [9, 10, 27]. This supports the idea of this mechanism as the cause of headache, compared to other suggested hypotheses such as direct viral invasion of the central nervous system, hypoxia or dehydration [13]. In addition, the clinical similarities between COVID-19 and headache associated to viral systemic infections are in this line [7].

Pain secondary to cytokine is thought to be secondary to the activation of nociceptive sensory neurons and the nerve inflammation by proinflammatory cytokines inducing central sensitization [28]. IL-23 and PIGF1 are both pro-inflammatory cytokines [29, 30] so the finding of a trend to significant higher levels in our sample is in this line. On the other hand, in our study we found elevated levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine with a major role in mitigating inflammation through the ability to inhibit synthesis of non-specific proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF [31], In view of its anti-inflammatory properties, the IL-10 elevated levels in our sample may represent a homeostatic response to counteract the effects of other cytokines released during acute COVID-19, reflecting a more intense immunologic response to the virus in patients who develop headache. This hypothesis could explain the better outcome in COVID-19 patients with headache, compared with those patients without headache, observed in previous studies [4, 14]. The role of many interleukins and cytokines in COVID-19 infection is still unknown, some of them could be different depending on the presence of comorbidities, while others could be more related with the clinical presentation and severity of the disease. The role of a pre-existing headache in the cytokine profile also needs to be clarified.

Finally, if our findings are confirmed by further studies, they might have relevant implications. The attribution of a central role to the cytokine storm in COVID-19 pathophysiology led to different therapeutic approaches targeting the pro-inflammatory body state [32] or different cytokines [33, 34]. In the same way, knowing the physiopathology of COVID-19 headache and which inflammatory factors are implicated, could be helpful in the search of targeting therapies for persistent or treatment resistant headache in COVID-19 patients.

Another striking finding in our study was the association of headache and anosmia in patients with COVID-19. This finding was also described in other previous studies [35, 36]. The possible underling mechanism of anosmia still remains unknown on the one hand, clinical studies suggested that it could be related with the binding of the virus to the angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 receptors in the respiratory mucosae [37] which could explain the frontal topography of the headache. On the other hand, other authors suggest an inflammatory underlying mechanism of anosmia, and in this line a previous study found that a proinflammatory cytokine -TNF alpha- was higher in the olfactory mucosa in patients with COVID-19 [38].

Despite both osmophobia and anosmia might be related with the olfactory nerve, this symptom may be hidden due to the presence of anosmia. The frequency of anosmia in the general population before the pandemic was almost testimonial and mainly related with other viral infection or Parkinson disease [39], while osmophobia is one of the most specific symptoms of migraine [40]. Some authors suggest that COVID-19 might unravel a personal “migrainous biology” in some cases [41], but this is also still to be disentangled.

This study has important limitations. As previously mentioned, the analytic parameters were obtained in the same first day of hospitalization, but in different moments of the disease, which may reflect different inflammatory stages. On the other hand, the sample size was small, which limited the power of the study. The sample only included hospitalized patients, which could imply a selection bias. Finally, there are some statistical issues, as the large number of parameters that were compared which could increase false positive results. Despite these limitations, we consider that this pilot study may be helpful for the design of future validation studies.

Conclusions

Selected cytokine levels are increased in COVID-19 patients with headache in comparison to COVID-19 patients without headache. The cross-sectional nature of our study impedes to draw any conclusions about causal relationship between cytokine levels and the headache. However, the higher levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 found in our sample in patients with headache may be interpreted as a response to proinflammatory cytokine storm, reflecting a more efficient immune response in these patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- STARD:

-

Standards for Reporting or Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- EGF:

-

Epidermal growth factor

- FGF-2:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- GRO:

-

Growth-regulated oncogene

- CXCL1:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1

- HGF:

-

Hepatocyte growth factor

- NGF:

-

Nerve growth factor

- LIF:

-

Leukaemia inhibitory factor

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IL-1RA:

-

Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

- IP-10:

-

Interferon gamma-induced protein 10

- CXCL10:

-

Hemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- CCL2:

-

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- MIP-1:

-

Macrophage inflammatory protein 1

- CCL3:

-

Chemokine (C-C-motif) ligand 3

- RANTES:

-

Regulated upon activation normal T Cell expressed and presumably secreted

- CCL5:

-

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5

- SDF-1:

-

Stromal-cell derived factor 1

- TNF:

-

Tumoral necrosis factor

- LTA:

-

Lymphotoxin alpha

- PDGF:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor

- PIGF-1:

-

Placental growth factor

- SCF:

-

Stem cell factor

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

References

Favas TT, Dev P, Chaurasia RN, Chakravarty K, Mishra R, Joshi D, Mishra VN, Kumar A, Singh VK, Pandey M, Pathak A (2020) Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions. Neurol Sci 41(12):3437–3470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04801-y

García-Azorín D, Trigo J, Talavera B, Martínez-Pías E, Sierra Á (2020) Porta-Etessam. Et al. frequency and type of red flags in patients with COVID-19 and headache: A series of 104 hospitalized patients. Headache 60(8):1664–1672. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13927

Porta-Etessam J, Matías-Guiu JA, González-García N, Gómez Iglesias P, Santos-Bueso E, Arriola-Villalobos P, García-Azorín D, Matías-Guiu J (2020) Spectrum of headaches associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: study of healthcare professionals. Headache 60(8):1697–1704. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13902

Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Martínez-Pías E, Talavera B, Hernández-Pérez I, Valle-Peñacoba G, Simón-Campo P, de Lera M, Chavarría-Miranda A, López-Sanz C, Gutiérrez-Sánchez M, Martínez-Velasco E, Pedraza M, Sierra Á, Gómez-Vicente B, Arenillas JF, Guerrero ÁL (2020) Factor associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain 21(1):94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8

Talavera B, García-Azorín D, Martínez-Pías E, Trigo J, Hernández-Pérez I, Valle-Peñacoba G, Simón-Campo P, de Lera M, Chavarría-Miranda A, López-Sanz C, Gutiérrez-Sánchez M, Martínez-Velasco E, Pedraza M, Sierra Á, Gómez-Vicente B, Guerrero Á, Arenillas JF (2020) Anosmia is associated with lower-in hospital mortality in COVID19. J Neurol Sci 419:117163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117163

Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Trigo J, de Luis-García R, Guerrero ÁL, Porta-Etessam J, García-Azorín D et al (2020) Deep phenotyping of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients via principal component analysis. Front Neurol 11:583870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.583870

Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, García-Iglesias C, Dueñas-Gutiérrez C, Guerrero ÁL (2020) Phenotypic characterization of acute headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2: An ICHD-3 validation study on 106 hospitalized patients. Cephalalgia 40(13):1432–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420965146

De Marinis M, Welch KM (1992) Headache associated with non-cephalic infections: classification and mechanisms. Cephalalgia 12(4):197–201. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.1992.1204197.x

Wang J, Jiang M, Chen X, Montaner LJ (2020) Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of 3939 COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J Leukoc Biol 108(1):17–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R

Fara A, Mitrev Z, Rosalia RA, Assas BM (2020) Cytokine storm and COVID-19: a chronicle of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Open Biol 10(9):200160. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.200160

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2018) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 38(1):1–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, Cooley LA, Dean NC, Fine MJ, Flanders SA, Griffin MR, Metersky ML, Musher DM, Restrepo MI, Whitney CG (2019) Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American thoracic society and infectious disease society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200(7):e45–e67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

Bobker SM, Robbins MS (2020) COVID-19 and headache: A primer for trainees. Headache 60(8):1806–1811. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13884

Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, Gallardo VJ, Ariton DM, Lallana S et al (2020) Headache; A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID19 clinical evolution. Principio del formulario Final del formulario Cephalalgia 40(13):1410–1421

Smith RS (1992) The cytokine theory of headache. Med Hypotheses 39(2):168–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9877(92)90181-B

Chapman PB, Lester TJ, Casper ES, Gabrilove JL, Wong GY, Kempin SJ, Gold PJ, Welt S, Warren RS, Starnes HF (1987) Clinical phamra- cology of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 5(12):1942–1951. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1987.5.12.1942

Fent K, Zbinden G (1987) Toxicity of interferon and interleukin. Trends Pharmacol Sci 8(3):100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-6147(87)90083-6

Kemper RH, Meijler WJ, Korf J, Ter Horst GJ (2001) Migraine and function of the immune system: a meta-analysis of clinical literature published between 1966 and 1999. Cephalalgia 21(5):549–557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00196.x

Covelli V, Munno I, Pellegrino NM, Di VA, Jirillo E, Buscaino GA (1990) Exaggerated spontaneous release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-cachectin in patients with migraine without aura. Acta Neurol 45:257–263

Covelli V, Munno I, Pellegrino NM, Attamura M, Decandia P, Marcuccio C et al (1991) Are TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta relevant in the pathogenesis of migraine without aura? Acta Neurol 13(2):205–211

Yucel M, Kotan D, Gurol Ciftci G, Ciftci IH, Cikriklar HI (2016) Serum levels of endocan, claudin-5 and cytokines in migraine. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20(5):930–936

Martelletti P, Stirparo G, Rinaldi C, Giacovazzo M (1993) Disruption of the immunopeptidergic network in dietary migraine. Headache 33(10):524–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3310524.x

Munno I, Marinaro M, Bassi A, Cassiano MA, Causarano V, Centonze V (2001) Immunological aspects in migraine: increase of IL-10 plasma levels during attack. Headache 41(8):764–767. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.01140.x

Koçer A, Koçer E, Memişoğullari R, Domaç FM, Yüksel H (2010) Interleukin-6 levels in tension headache patients. Clin J Pain 26(8):690–693. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e8d9b6

Domingues RB, Duarte H, Rocha NP, Teixeira AL (2015) Increased serum levels of interleukin-8 in patients with tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 35(9):801–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414559734

Eccles R (2005) Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis 5(11):718–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X

Han H, Ma Q, Li C, Liu R, Zhao L, Wang W, Zhang P, Liu X, Gao G, Liu F, Jiang Y, Cheng X, Zhu C, Xia Y (2020) Profiling serum cytokines in COVID19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors. Emerg Microbes Infect 9(1):1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1770129

Zhang JM, An J (2007) Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 45(2):27–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e

Schmitt H, Neurath MF, Atreya R (2021) Role of the IL23/IL17 pathway in Crohn’s disease. Front Immunol 12:622934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.622934

Oura H, Bertoncini J, Velasco P, Brown LF, Carmeliet P, Detmar M (2003) A critical role of placental growth factor in the induction of inflammation and edema formation. Blood 101(2):560–567. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-05-1516

Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S (1993) Human IL-10 is pro- duced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol 150:353–360

WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group, Sterne JA, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, Angus DC, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2020; 324: 1330

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ et al (2020) COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 396:1033

Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Della-Torre E, Ripa M, Canetti D et al (2020) Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2:e325

Rocha-Filho PAS, Magalhães JE (2020) Headache associated with COVID-19: frequency, characteristics and association with anosmia and ageusia. Cephalalgia 40(13):1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420966770

Martelletti P, Bentivegna E, Luciani M, Spuntarelli V (2020) Headache as a prognostic factor for COVID-19. Time to re-evaluate. SN Compr Clin Med 26:1–2

Chen M, Shen W, Rowan NR, Kulaga H, Hillel A, Ramanathan M Jr, Lane AP (2020) Elevated ACE-2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication. Eur Respir J 56(3):2001948. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01948-2020

A-Torabi A, Mohammadbagheri E, Akbari Dilmaghani N, Bayat AH, Fathi M, Vakili K et al (2020) Proinflammatory cytokines in the olfactory mucosa result in COVID-19 induced anosmia. ACS Chem Neurosci 11(13):1909–1913. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00249

Tarakad A, Jankovic J (2017) Anosmia and Ageusia in Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 133:541–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2017.05.028

Lovati C, Lombardo D, Peruzzo S, Bellotti A, Capogrosso CA, Pantoni L (2020) Osmophobia in migraine: multifactorial investigation and population-based survey. Neurol Sci 41(Suppl 2):453–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04656-3

Bolay H, Gül A, Baykan B (2020) COVID-19 is a real headache! Headache 60(7):1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13856

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the collaboration of the Nursing staff and the Research Unit from the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (Spain) for the assistance during project development.

Funding

We would like to thank Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) for granting the COV20–00491 project in the call for expressions of interest for the financing of research projects on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease under the COVID-19 fund: code 07.04.467804.74011 and Regional Health Administration, Gerencia regional de Salud, Castilla y León (GRS: 2289/A/2020). No funding source had any role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation, writing or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT and DGA were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. ASM analysed the data. ATV collected the data. ET managed the resources and analysed the data. ALG conceptualized the study. PMP processed the samples and performed the experiments. HGB managed the resources, processed the samples, performed the experiments and analysed data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Clinical Research Ethics Committee of East Valladolid Area approved the study.

Consent for publication

All the patients read and signed informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Severity of COVID-19 disease according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Trigo, J., García-Azorín, D., Sierra-Mencía, Á. et al. Cytokine and interleukin profile in patients with headache and COVID-19: A pilot, CASE-control, study on 104 patients. J Headache Pain 22, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01268-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01268-w