Abstract

Advances in whole genome amplification and next-generation sequencing methods have enabled genomic analyses of single cells, and these techniques are now beginning to be used to detect genomic lesions in individual cancer cells. Previous approaches have been unable to resolve genomic differences in complex mixtures of cells, such as heterogeneous tumors, despite the importance of characterizing such tumors for cancer treatment. Sequencing of single cells is likely to improve several aspects of medicine, including the early detection of rare tumor cells, monitoring of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), measuring intratumor heterogeneity, and guiding chemotherapy. In this review we discuss the challenges and technical aspects of single-cell sequencing, with a strong focus on genomic copy number, and discuss how this information can be used to diagnose and treat cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

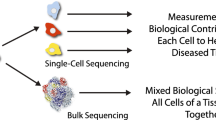

The value of molecular methods for cancer medicine stems from the enormous breadth of information that can be obtained from a single tumor sample. Microarrays assess thousands of transcripts, or millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) can reveal copy number and genetic aberrations at base pair resolution. However, because most applications require bulk DNA or RNA from over 100,000 cells, they are limited to providing global information on the average state of the population of cells. Solid tumors are complex mixtures of cells including non-cancerous fibroblasts, endothelial cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages that often contribute more than 50% of the total DNA or RNA extracted. This admixture can mask the signal from the cancer cells and thus complicate the inter- and intra-tumor comparisons, which are the basis of molecular classification methods.

In addition, solid tumors are often composed of multiple clonal subpopulations [1–3], and this heterogeneity further confounds the analysis of clinical samples. Single-cell genomic methods have the capacity to resolve complex mixtures of cells in tumors. When multiple clones are present in a tumor, molecular assays reflect an average signal of the population, or, alternatively, only the signal from the dominant clone, which may not be the most malignant clone present in the tumor. This becomes particularly important as molecular assays are employed for directing targeted therapy, as in the use of ERBB2 (Her2-neu) gene amplification to identify patients likely to respond to Herceptin (trastuzumab) treatment in breast cancer, where 5% to 30% of all patients have been reported to exhibit such genetic heterogeneity [4–7].

Aneuploidy is another hallmark of cancer [8], and the genetic lineage of a tumor is indelibly written in its genomic profile. While whole genomic sequencing of a single cell is not possible using current technology, copy number profiling of single cells using sparse sequencing or microarrays can provide a robust measure of this genomic complexity and insight into the character of the tumor. This is evident in the progress that has been made in many studies of single-cell genomic copy number [9–14]. In principle, it should also be possible to obtain a partial representation of the transcriptome from a single cell by NGS and a few successes have been reported for whole transcriptome analysis in blastocyst cells [15, 16]; however, as yet, this method has not been successfully applied to single cancer cells.

The clinical value of single-cell genomic methods will be in profiling scarce cancer cells in clinical samples, monitoring CTCs, and detecting rare clones that may be resistant to chemotherapy (Figure 1). These applications are likely to improve all three major themes of oncology: detection, progression, and prediction of therapeutic efficacy. In this review, we outline the current methods and those in development for isolating single cells and analyzing their genomic profile, with a particular focus on profiling genomic copy number.

Medical applications of single-cell sequencing. (a) Profiling of rare tumor cells in scarce clinical samples, such as fine-needle aspirates of breast lesions. (b) Isolation and profiling of circulating tumor cells in the blood. (c) Identification and profiling of rare chemoresistant cells before and after adjuvant therapy.

Background

Although genomic profiling by microarray comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) has been in clinical use for constitutional genetic disorders for some time, its use in profiling cancers has been largely limited to basic research. Its potential for clinical utility is yet to be realized. Specific genomic events such as Her2-neu amplification as a target for Herceptin are accepted clinical markers, and genome-wide profiling for copy number has been used only in preclinical studies and only recently been incorporated into clinical trial protocols [17]. However, in cohort studies, classes of genomic copy number profiles of patients have shown strong correlation with patient survival [18, 19]. Until the breakthrough of NGS, the highest resolution for identifying copy number variations was achieved through microarray-based methods, which could detect amplifications and deletions in cancer genomes, but could not discern copy neutral alterations such as translocations or inversions. NGS has changed the perspective on genome profiling, since DNA sequencing has the potential to identify structural changes, including gene fusions and even point mutations, in addition to copy number. However, the cost of profiling a cancer genome at base pair resolution remains out of range for routine clinical use, and calling mutations is subject to ambiguities as a result of tumor heterogeneity, when DNA is obtained from bulk tumor tissue. The application of NGS to genomic profiling of single cells developed by the Wigler group and Cold Spring Harbor Lab and described here has the potential to not only acquire an even greater level of information from tumors, such the variety of cells present, but further to obtain genetic information from the rare cells that may be the most malignant.

Isolating single cells

To study a single cell it must first be isolated from cell culture or a tissue sample in a manner that preserves biological integrity. Several methods are available to accomplish this, including micromanipulation, laser-capture microdissection (LCM) and flow cytometry (Figure 2a-c). Micromanipulation of individual cells using a transfer pipette has been used for isolating single cells from culture or liquid samples such as sperm, saliva or blood. This method is readily accessible but labor intensive, and cells are subject to mechanical shearing. LCM allows single cells to be isolated directly from tissue sections, making it desirable for clinical applications. This approach requires that tissues be sectioned, mounted and stained so that they can be visualized to guide the isolation process. LCM has the advantage of allowing single cells to be isolated directly from morphological structures, such as ducts or lobules in the breast. Furthermore, tissue sections can be stained with fluorescent or chromogenic antibodies to identify specific cell types of interest. The disadvantage of LCM for genomic profiling is that some nuclei will inevitably be sliced in the course of tissue sectioning, causing loss of chromosome segments and generating artifacts in the data.

Isolating single cells and techniques for genomic profiling. (a-c) Single-cell isolation methods. (d-f) Single-cell genomic profiling techniques. (a) Micromanipulation, (b) laser-capture microdissection (LCM), (c) fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), (d) cytological methods to visualize chromosomes in single cells, (e) whole genome amplification (WGA) and microarray comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), (f) WGA and next-generation sequencing.

Flow cytometry using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is by far the most efficient method for isolating large numbers of single cells or nuclei from liquid suspensions. Although it requires sophisticated and expensive instrumentation, FACS is readily available at most hospitals and research institutions, and is used routinely to sort cells from hematopoietic cancers. Several instruments such as the BD Aria II/III (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and the Beckman Coulter MO-FLO (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) have been optimized for sorting single cells into 96-well plates for subcloning cell cultures. FACS has the added advantage that cells can be labeled with fluorescent antibodies or nuclear stains (4',6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole dihydrochloride (DAPI)) and sorted into different fractions for downstream analysis.

Methods for single-cell genomic profiling

Several methods have been developed to measure genome-wide information of single cells, including cytological approaches, aCGH and single-cell sequencing (Figure 2d-f). Some of the earliest methods to investigate the genetic information contained in single cells emerged in the 1970s in the fields of cytology and immunology. Cytological methods such as spectral karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and Giemsa staining enabled the first qualitative analysis of genomic rearrangements in single tumor cells (illustrated in Figure 2d). In the 1980s, the advent of PCR enabled immunologists to investigate genomic rearrangements that occur in immunocytes, by directly amplifying and sequencing DNA from single cells [20–22]. Together, these tools provided the first insight into the remarkable genetic heterogeneity that characterizes solid tumors [23–28].

While PCR could amplify DNA from an individual locus in a single cell, it could not amplify the entire human genome in a single reaction. Progress was made using PCR-based strategies such as primer extension pre-amplification [29] to amplify the genome of a single cell; however, these strategies were limited in coverage when applied to human genomes. A major milestone occurred with the discovery of two DNA polymerases that displayed remarkable processivity for DNA synthesis: Phi29 (Φ29) isolated from the Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage, and Bst polymerase isolated from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Pioneering work in the early 2000s demonstrated that these enzymes could amplify the human genome over 1,000-fold through a mechanism called multiple displacement amplification [30, 31]. This approach, called whole genome amplification (WGA), has since been made commercially available (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; Rubicon Genomics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Coupling WGA with array CGH enabled several groups to begin measuring genomic copy number in small populations of cells, and even single cells (Figure 2e). These studies showed that it is possible to profile copy number in single cells in various cancer types, including CTCs [9, 12, 32], colon cancer cell lines [13] and renal cancer cell lines [14]. While pioneering, these studies were also challenged by limited resolution and reproducibility. However, in practice, probe-based approaches such as aCGH microarrays are problematic for measuring copy number using methods such as WGA, where amplification is not uniform across the genome. WGA fragments amplified from single cells are sparsely distributed across the genome, representing no more than 10% of the unique human sequence [10]. This results in zero coverage for up to 90% of probes, ultimately leading to decreased signal to noise ratios and high standard deviations in copy number signal.

An alternative approach is to use NGS. This method provides a major advantage over aCGH for measuring WGA fragments because it provides a non-targeted approach to sample the genome. Instead of differential hybridization to specific probes, sequence reads are integrated over contiguous and sequential lengths of the genome and all amplified sequences are used to calculate copy number. In a recently published study, we combined NGS with FACS and WGA in a method called single-nucleus sequencing (SNS) to measure high-resolution (approximately 50 kb) copy number profiles of single cells [10]. Flow-sorting of DAPI-stained nuclei isolated from tumor or other tissue permits deposition of single nuclei into individual wells of a multiwell plate, but, moreover, permits sorting cells by total DNA content. This step purifies normal nuclei (2 N) from aneuploid tumor nuclei (not 2 N), and avoids collecting degraded nuclei. We then use WGA to amplify the DNA from each well by GenomePlex (Sigma-Genosys, The Woodlands, TX, USA) to yield a collection of short fragments, covering approximately 6% (mean 5.95%, SEM ± 0.229, n = 200) of the human genome uniquely [10], which are then processed for Illumina sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) (Figure 3a). For copy number profiling, deep sequencing is not required. Instead, the SNS method requires only sparse read depth (as few as 2 million uniquely mapped 76 bp single-end reads) evenly distributed along the genome. For this application, Illumina sequencing is preferred over other NGS platforms because it produces the highest number of short reads across the genome at the lowest cost.

Single-nucleus sequencing of breast tumors. (a) Single-nucleus sequencing involves isolating nuclei, staining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole dihydrochloride (DAPI), flow-sorting by total DNA content, whole genome amplification (WGA), Illumina library construction, and quantifying genomic copy number using sequence read depth. (b) Phylogenetic tree constructed from single-cell copy number profiles of a monogenomic breast tumor. (c) Phylogenetic tree constructed using single-cell copy number profiles from a polygenomic breast tumor, showing three clonal subpopulations of tumor cells.

To calculate the genomic copy number of a single cell, the sequence reads are grouped into intervals or ‘bins’ across the genome, providing a measure of copy number based on read density in each of 50,000 bins, resulting in a resolution of 50 kb across the genome. In contrast to previous studies that measure copy number from sequence read depth using fixed bin intervals across the human genome [33–37], we have developed an algorithm that uses variable length bins to correct for artifacts associates with WGA and mapping. The length of each bin is adjusted in size based on a mapping simulation using random DNA sequences, depending on the expected unique read density within each interval. This corrects regions of the genome with repetitive elements (where fewer reads map), and biases introduced, such as GC content. The variable bins are then segmented using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistical test [1, 38]. Alternative methods for sequence data segmentation, such as hidden Markov models, have been developed [33], but have not yet been applied to sparse single-cell data. In practice, KS segmentation algorithms work well for complex aneuploid cancer genomes that contain many variable copy number states, whereas hidden Markov models are better suited for simple cancer genomes with fewer rearrangements, and normal individuals with fewer copy number states. To determine the copy number states in sparse single-cell data, we count the reads in variable bins and segments with KS, then use a Gaussian smoothed kernel density function to sample all of the copy number states and determine the ground state interval. This interval is used to linearly transform the data, and round to the nearest integer, resulting in the absolute copy number profile of each single cell [10]. This processing allows amplification artifacts associated with WGA to be mitigated informatically, reducing biases associated with GC content [9, 14, 39, 40] and mapability of the human genome [41]. Other artifacts, such as over-replicated loci (‘pileups’), as previously reported in WGA [40, 42, 43], do occur, but they are not at recurrent locations in different cells, and are sufficiently randomly distributed and sparse so as not to affect counting over the breadth of a bin, when the mean interval size is 50 kb. While some WGA methods have reported the generation of chimeric DNA molecules in bacteria [44], these artifacts would mainly affect paired-end mappings of structural rearrangements, not single-end read copy number measurements that rely on sequence read depth. In summary, NGS provides a powerful tool to mitigate artifacts previously associated with quantifying copy number in single cells amplified by WGA, and eliminates the need for a reference genome to normalize artifacts, making it possible to calculate absolute copy number from single cells.

Clinical application of single-cell sequencing

While single-cell genomic methods such as SNS are feasible in a research setting, they will not be useful in the clinic until advances are made in reducing the cost and time of sequencing. Fortunately, the cost of DNA sequencing is falling precipitously as a direct result of industry competition and technological innovation. Sequencing has an additional benefit over microarrays in the potential for massive multiplexing of samples using barcoding strategies. Barcoding involves adding a specific 4 to 6 base oligonucleotide sequence to each library as it is amplified, so that samples can be pooled together in a single sequencing reaction [45, 46]. After sequencing, the reads are deconvoluted by their unique barcodes for downstream analysis. With the current throughput of the Illumina HiSeq2000, it is possible to sequence up to 25 single cells on a single-flow cell lane, thus allowing 200 single cells to be profiled in a single run. Moreover, by decreasing the genomic resolution of each single-cell copy number profile (for example from 50 kb to 500 kb) it is possible to profile hundreds of cells in parallel on a single lane, or thousands on a run, making single-cell profiling economically feasible for clinical applications.

A major application of single-cell sequencing will be in the detection of rare tumor cells in clinical samples, where fewer than a hundred cells are typically available. These samples include body fluids such as lymph, blood, sputum, urine, or vaginal or prostate fluid, as well clinical biopsy samples such as fine-needle aspirates (Figure 1a) or core biopsy specimens. In breast cancer, patients often undergo fine-needle aspirates, nipple aspiration, ductal lavages or core biopsies; however, genomic analysis is rarely applied to these samples because of limited DNA or RNA. Early stage breast cancers, such as low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ, which are detected by these methods, present a formidable challenge to oncologists, because only 5% to 10% of patients with DCIS typically progress to invasive carcinomas [47–51]. Thus, it is difficult for oncologists to determine how aggressively to treat each individual patient. Studies of DCIS using immunohistochemistry support the idea that many early stage breast cancers exhibit extensive heterogeneity [52]. Measuring tumor heterogeneity in these scarce clinical samples by genomic methods may provide important predictive information on whether these tumors will evolve and become invasive carcinomas, and they may lead to better treatment decisions by oncologists.

Early detection using circulating tumor cells

Another major clinical application of single-cell sequencing will be in the genomic profiling of copy number or sequence mutations in CTCs and disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) (Figure 1b). Although whole genome sequencing of single CTCs is not yet technically feasible, with future innovations, such data may provide important information for monitoring and diagnosing cancer patients. CTCs are cells that intravasate into the circulatory system from the primary tumor, while DTCs are cells that disseminate into tissues such the bone. Unlike other cells in the circulation, CTCs often contain epithelial surface markers (such as epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)) that allow them to be distinguished from other blood cells. CTCs present an opportunity to obtain a non-invasive ‘fluid biopsy’ that would provide an indication of cancer activity in a patient, and also provide genetic information that could direct therapy over the course of treatment. In a recent phase II clinical study, the presence of epithelial cells (non-leukocytes) in the blood or other fluids correlated strongly with active metastasis and decreased survival in patients with breast cancer [53]. Similarly, in melanoma it was shown that counting more than two CTCs in the blood correlated strongly with a marked decrease in survival from 12 months to 2 months [54]. In breast cancer, DTCs in the bone marrow (micrometastases) have also correlated with poor overall patient survival [55].While studies that count CTCs or DTCs clearly have prognostic value, more detailed characterization of their genomic lesions are necessary to determine whether they can help guide adjuvant or chemotherapy.

Several new methods have been developed to count the number of CTCs in blood, and to perform limited marker analysis on isolated CTCs using immunohistochemistry and FISH. These methods generally depend on antibodies against EpCAM to physically isolate a few epithelial cells from the nearly ten million non-epithelial leukocytes in a typical blood draw. CellSearch (Veridex, LLC, Raritan, NJ, USA) uses a series of immunomagnetic beads with EpCAM markers to isolate tumor cells and stain them with DAPI to visualize the nucleus. This system also uses CD45 antibodies to negatively select immune cells from the blood samples. Although CellSearch is the only instrument that is currently approved for counting CTCs in the clinic, a number of other methods are in development, and these are based on microchips [56], FACS [57, 58] or immunomagnetic beads [54] that allow CTCs to be physically isolated. However, a common drawback of all methods is that they depend on EpCAM markers that are not 100% specific (antibodies can bind to surface receptors on blood cells) and the methods for distinguishing actual tumor cells from contaminants are not dependable [56].

Investigating the diagnostic value of CTCs with single-cell sequencing has two advantages: impure mixtures can be resolved, and limited amounts of input DNA can be analyzed. Even a single CTC in an average 7.5 ml blood draw (which is often the level found in patients) can be analyzed to provide a genomic profile of copy number aberrations. By profiling multiple samples from patients, such as the primary tumor, metastasis and CTCs, it would be possible to trace an evolutionary lineage and determine the pathways of progression and site of origin.

Monitoring or detecting CTCs or DTCs in normal patients may also provide a non-invasive approach for the early detection of cancer. Recent studies have shown that many patients with non-metastatic primary tumors show evidence of CTCs [53, 59]. While the function of these cells is largely unknown, several studies have demonstrated prognostic value of CTCs using gene-specific molecular assays such as reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR [60–62]. Single-cell sequencing could greatly improve the prognostic value of such methods [63]. Moreover, if CTCs generally share the mutational profile of the primary tumors (from which they are shed), then they could provide a powerful non-invasive approach to detecting early signs of cancer. One day, a general physician may be able to draw a blood sample during a routine check-up and profile CTCs indicating the presence of a primary tumor somewhere in the body. If these genomic profiles reveal mutations in cancer genes, then medical imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) could be pursued to identify the primary tumor site for biopsy and treatment. CTC monitoring would also have important applications in monitoring residual disease after adjuvant therapy to ensure that the patients remain in remission.

The analysis of scarce tumor cells may also improve the early detection of cancers. Smokers could have their sputum screened on regular basis to identify rare tumor cells with genomic aberrations that provide an early indication of lung cancer. Sperm ejaculates contain a significant amount of prostate fluid that may contain rare prostate cancer cells. Such cells could be purified from sperm using established biomarkers such as prostate-specific antigen [64] and profiled by single-cell sequencing. Similarly, it may be possible to isolate ovarian cancer cells from vaginal fluid using established biomarkers, such as ERCC5 [65] or HE4 [66], for genomic profiling. The genomic profile of these cells may provide useful information on the lineage of the cell and from which organ it has been shed. Moreover, if the genomic copy number profiles of rare tumor cells accurately represent the genetic lesions in the primary tumor, then they may provide an opportunity for targeted therapy. Previous work has shown that classes of genomic copy number profiles correlate with survival [18], and thus the profiles of rare tumor cells may have predictive value in assessing the severity of the primary cancer from which they have been shed.

Investigating tumor heterogeneity with SNS

Tumor heterogeneity has long been reported in morphological [67–70] and genetic [26, 28, 71–76] studies of solid tumors, and more recently in genomic studies [1–3, 10, 77–81], transcriptional profiles [82, 83] and protein levels [52, 84] of cells within the same tumor (summarized in Table 1). Heterogeneous tumors present a formidable challenge to clinical diagnostics, because sampling single regions within a tumor may not represent the population as a whole. Tumor heterogeneity also confounds basic research studies that investigate the fundamental basis of tumor progression and evolution. Most current genomic methods require large quantities of input DNA, and thus their measurements represent an average signal across the population. In order to study tumor subpopulations, several studies have stratified cells using regional macrodissection [1, 2, 79, 85], DNA ploidy [1, 86], LCM [78, 87] or surface receptors [3] prior to applying genomic methods. While these approaches do increase the purity of the subpopulations, they remain admixtures. To fully resolve such complex mixtures, it is necessary to isolate and study the genomes of single cells.

In the single-cell sequencing study described above, we applied SNS to profile hundreds of single cells from two primary breast carcinomas to investigate substructure and infer genomic evolution [10]. For each tumor we quantified the genomic copy number profile of each single cell and constructed phylogenetic trees (Figure 3). Our analysis showed that one tumor (T16) was monogenomic, consisting of cells with tightly conserved copy number profiles throughout the tumor mass, and was apparently the result of a single major clonal expansion (Figure 3b). In contrast, the second breast tumor (T10) was polygenomic (Figure 3c), displaying three major clonal subpopulations that shared a common genetic lineage. These subpopulations were organized into different regions of the tumor mass: the H subpopulation occupied the upper sectors of the tumor (S1 to S3), while the other two tumor subpopulations (AA and AB) occupied the lower regions (S4 to S6). The AB tumor subpopulation in the lower regions contained a massive amplification of the KRAS oncogene and homozygous deletions of the EFNA5 and COL4A5 tumor suppressors. When applied to clinical biopsy or tumor samples, such phylogenetic trees are likely to be useful for improving the clinical sampling of tumors for diagnostics, and may eventually aid in guiding targeted therapies for the patient.

Response to chemotherapy

Tumor heterogeneity is likely to play an important role in the response to chemotherapy [88]. From a Darwinian perspective, tumors with the most diverse allele frequencies will have the highest probability of surviving a catastrophic selection pressure such as a cytotoxic agent or targeted therapy [89, 90]. A major question revolves around whether resistant clones are pre-existing in the primary tumor (prior to treatment) or whether they emerge in response to adjuvant therapy by acquiring de novo mutations. Another important question is whether heterogeneous tumors generally show a poorer response to adjuvant therapy. Using samples of millions of cells, recent studies in cervical cancer treated with cis-platinum [79] and ovarian carcinomas treated with chemoradiotherapy [91] have begun to investigate these questions by profiling tumors for genomic copy number before and after treatment. Both studies reported detecting some heterogeneous tumors with pre-existing resistant subpopulations that expanded further after treatment. However, since these studies are based on signals derived from populations of cells, their results are likely to underestimate the total extent of genomic heterogeneity and frequency of resistant clones in the primary tumors. These questions are better addressed using single-cell sequencing methods, because they can provide a fuller picture of the extent of genomic heterogeneity in the primary tumor. The degree of genomic heterogeneity may itself provide useful prognostic information, guiding patients who are deciding on whether to elect chemotherapy and the devastating side-effects that often accompany it. In theory, patients with monogenomic tumors will respond better and show better overall survival compared with patients with polygenomic tumors, which may have a higher probability of developing or having resistant clones, that is, more fuel for evolution. Single-cell sequencing can in principle also provide a higher sensitivity for detecting rare chemoresistant clones in primary tumors (Figure 1c). Such methods will enable the research community to investigate questions of whether resistant clones are pre-existing in primary tumors or arise in response to therapies. Furthermore, by multiplexing and profiling hundreds of single cells from a patient’s tumor, it will possible to develop a more comprehensive picture of the total genomic diversity in a tumor before and after adjuvant therapy.

Future directions

Single-cell sequencing methods such as SNS provide an unprecedented view of the genomic diversity within tumors and provide the means to detect and analyze the genomes of rare cancer cells. While cancer genome studies on bulk tissue samples can provide a global spectrum of mutations that occur within a patient [81, 92], they cannot determine whether all of the tumor cells contain the full set of mutations, or alternatively whether different subpopulations contain subsets of these mutations that in combination drive tumor progression. Moreover, single-cell sequencing has the potential to greatly improve our fundamental understanding of how tumors evolve and metastasize. While single-cell sequencing methods using WGA are currently limited to low coverage of the human genome (approximately 6%), emerging third-generation sequencing technologies such as that developed by Pacific Biosystems (Lacey, WA, USA) [93] may greatly improve coverage through single-molecule sequencing, by requiring lower amounts of input DNA.

In summary, the future medical applications of single-cell sequencing will be in early detection, monitoring CTCs during treatment of metastatic patients, and measuring the genomic diversity of solid tumors. While pathologists can currently observe thousands of single cells from a cancer patient under the microscope, they are limited to evaluating copy number at a specific locus for which FISH probes are available. Genomic copy number profiling of single cells can provide a fuller picture of the genome, allowing thousands of potentially aberrant cancer genes to be identified, thereby providing the oncologist with more information on which to base treatment decisions. Another important medical application of single-cell sequencing will be in the profiling of CTCs for monitoring disease during the treatment of metastatic disease. While previous studies have shown value in the simple counting of epithelial cells in the blood [53, 54], copy number profiling of single CTCs may provide a fuller picture, allowing clinicians to identify genomic amplifications of oncogenes and deletions of tumor suppressors. Such methods will also allow clinicians to monitor CTCs over time following adjuvant or chemotherapy, to determine if the tumor is likely to show recurrence.

The major challenge ahead for translating single-cell methods into the clinic will be the innovation of multiplexing strategies to profile hundreds of single cells quickly and at a reasonable cost. Another important aspect is to develop these methods for paraffin-embedded tissues (rather than frozen), since many samples are routinely processed in this manner in the clinic. When future innovations allow whole genome sequencing of single tumor cells, oncologists will also be able to obtain the full spectrum of genomic sequence mutations in cancer genes from scarce clinical samples. However, this remains a major technical challenge, and is likely to be the intense focus of both academia and industry in the coming years. These methods are likely to improve all three major themes of medicine: prognostics, diagnostics and chemotherapy, ultimately improving the treatment and survival of cancer patients.

Abbreviations

- aCGH:

-

microarray comparative genomic hybridization

- CTC:

-

circulating tumor cell

- DAPI:

-

4',6-diamidino-2-phenyl indole dihydrochloride

- DCIS:

-

ductal carcinoma in situ

- DTC:

-

disseminated tumor cell

- EpCAM:

-

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- FACS:

-

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FISH:

-

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- KS:

-

Kolmogorov-Smirnov

- LCM:

-

laser-capture microdissection

- NGS:

-

next-generation sequencing

- SNP:

-

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SNS:

-

single-nucleus sequencing

- WGA:

-

whole genome amplification.

References

Navin N, Krasnitz A, Rodgers L, Cook K, Meth J, Kendall J, Riggs M, Eberling Y, Troge J, Grubor V, Levy D, Lundin P, Månér S, Zetterberg A, Hicks J, Wigler M: Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res. 2010, 20: 68-80. 10.1101/gr.099622.109.

Torres L, Ribeiro FR, Pandis N, Andersen JA, Heim S, Teixeira MR: Intratumor genomic heterogeneity in breast cancer with clonal divergence between primary carcinomas and lymph node metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 102: 143-155. 10.1007/s10549-006-9317-6.

Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Argani P, Weremowicz S, Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, Nikolskaya T, Serebryiskaya T, Beroukhim R, Hu M, Halushka MK, Sukumar S, Parker LM, Anderson KS, Harris LN, Garber JE, Richardson AL, Schnitt SJ, Nikolsky Y, Gelman RS, Polyak K: Molecular definition of breast tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Cell. 2007, 11: 259-273. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.013.

Vance GH, Barry TS, Bloom KJ, Fitzgibbons PL, Hicks DG, Jenkins RB, Persons DL, Tubbs RR, Hammond ME, College of American Pathologists: Genetic heterogeneity in HER2 testing in breast cancer: panel summary and guidelines. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009, 133: 611-612.

Brunelli M, Manfrin E, Martignoni G, Miller K, Remo A, Reghellin D, Bersani S, Gobbo S, Eccher A, Chilosi M, Bonetti F: Genotypic intratumoral heterogeneity in breast carcinoma with HER2/neu amplification: evaluation according to ASCO/CAP criteria. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009, 131: 678-682. 10.1309/AJCP09VUTZWZXBMJ.

Cottu PH, Asselah J, Lae M, Pierga JY, Diéras V, Mignot L, Sigal-Zafrani B, Vincent-Salomon A: Intratumoral heterogeneity of HER2/neu expression and its consequences for the management of advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008, 19: 595-597.

Hanna W, Nofech-Mozes S, Kahn HJ: Intratumoral heterogeneity of HER2/neu in breast cancer - a rare event. Breast J. 2007, 13: 122-129. 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00396.x.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011, 144: 646-674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

Fuhrmann C, Schmidt-Kittler O, Stoecklein NH, Petat-Dutter K, Vay C, Bockler K, Reinhardt R, Ragg T, Klein CA: High-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization of single micrometastatic tumor cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36: e39-10.1093/nar/gkn101.

Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, Andrews P, Rodgers L, McIndoo J, Cook K, Stepansky A, Levy D, Esposito D, Muthuswamy L, Krasnitz A, McCombie WR, Hicks J, Wigler M: Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011, 472: 90-94. 10.1038/nature09807.

Klein CA, Schmidt-Kittler O, Schardt JA, Pantel K, Speicher MR, Riethmüller G: Comparative genomic hybridization, loss of heterozygosity, and DNA sequence analysis of single cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 4494-4499. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4494.

Stoecklein NH, Hosch SB, Bezler M, Stern F, Hartmann CH, Vay C, Siegmund A, Scheunemann P, Schurr P, Knoefel WT, Verde PE, Reichelt U, Erbersdobler A, Grau R, Ullrich A, Izbicki JR, Klein CA: Direct genetic analysis of single disseminated cancer cells for prediction of outcome and therapy selection in esophageal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008, 13: 441-453. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.005.

Fiegler H, Geigl JB, Langer S, Rigler D, Porter K, Unger K, Carter NP, Speicher MR: High resolution array-CGH analysis of single cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: e15-10.1093/nar/gkl1030.

Geigl JB, Obenauf AC, Waldispuehl-Geigl J, Hoffmann EM, Auer M, Hörmann M, Fischer M, Trajanoski Z, Schenk MA, Baumbusch LO, Speicher MR: Identification of small gains and losses in single cells after whole genome amplification on tiling oligo arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37: e105-10.1093/nar/gkp526.

Tang F, Barbacioru C, Wang Y, Nordman E, Lee C, Xu N, Wang X, Bodeau J, Tuch BB, Siddiqui A, Lao K, Surani MA: mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods. 2009, 6: 377-382. 10.1038/nmeth.1315.

Tang F, Barbacioru C, Bao S, Lee C, Nordman E, Wang X, Lao K, Surani MA: Tracing the derivation of embryonic stem cells from the inner cell mass by single-cell RNA-Seq analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010, 6: 468-478. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.015.

Barker AD, Sigman CC, Kelloff GJ, Hylton NM, Berry DA, Esserman LJ: I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009, 86: 97-100. 10.1038/clpt.2009.68.

Hicks J, Krasnitz A, Lakshmi B, Navin NE, Riggs M, Leibu E, Esposito D, Alexander J, Troge J, Grubor V, Yoon S, Wigler M, Ye K, Børresen-Dale AL, Naume B, Schlicting E, Norton L, Hägerström T, Skoog L, Auer G, Månér S, Lundin P, Zetterberg A: Novel patterns of genome rearrangement and their association with survival in breast cancer. Genome Res. 2006, 16: 1465-1479. 10.1101/gr.5460106.

Chin SF, Teschendorff AE, Marioni JC, Wang Y, Barbosa-Morais NL, Thorne NP, Costa JL, Pinder SE, van de Wiel MA, Green AR, Ellis IO, Porter PL, Tavaré S, Brenton JD, Ylstra B, Caldas C: High-resolution aCGH and expression profiling identifies a novel genomic subtype of ER negative breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2007, 8: R215-10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r215.

Gellrich S, Golembowski S, Audring H, Jahn S, Sterry W: Molecular analysis of the immunoglobulin VH gene rearrangement in a primary cutaneous immunoblastic B-cell lymphoma by micromanipulation and single-cell PCR. J Invest Dermatol. 1997, 109: 541-545. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12336753.

Maryanski JL, Jongeneel CV, Bucher P, Casanova JL, Walker PR: Single-cell PCR analysis of TCR repertoires selected by antigen in vivo: a high magnitude CD8 response is comprised of very few clones. Immunity. 1996, 4: 47-55. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80297-6.

Roers A, Hansmann ML, Rajewsky K, Küppers R: Single-cell PCR analysis of T helper cells in human lymph node germinal centers. Am J Pathol. 2000, 156: 1067-1071. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64974-7.

Coons SW, Johnson PC, Shapiro JR: Cytogenetic and flow cytometry DNA analysis of regional heterogeneity in a low grade human glioma. Cancer Res. 1995, 55: 1569-1577.

Fiegl M, Tueni C, Schenk T, Jakesz R, Gnant M, Reiner A, Rudas M, Pirc-Danoewinata H, Marosi C, Huber H: Interphase cytogenetics reveals a high incidence of aneuploidy and intra-tumour heterogeneity in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995, 72: 51-55. 10.1038/bjc.1995.276.

Pandis N, Jin Y, Gorunova L, Petersson C, Bardi G, Idvall I, Johansson B, Ingvar C, Mandahl N, Mitelman F: Chromosome analysis of 97 primary breast carcinomas: identification of eight karyotypic subgroups. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995, 12: 173-185. 10.1002/gcc.2870120304.

Sauter G, Moch H, Gasser TC, Mihatsch MJ, Waldman FM: Heterogeneity of chromosome 17 and erbB-2 gene copy number in primary and metastatic bladder cancer. Cytometry. 1995, 21: 40-46. 10.1002/cyto.990210109.

Teixeira MR, Pandis N, Bardi G, Andersen JA, Mitelman F, Heim S: Clonal heterogeneity in breast cancer: karyotypic comparisons of multiple intra- and extra-tumorous samples from 3 patients. Int J Cancer. 1995, 63: 63-68. 10.1002/ijc.2910630113.

Farabegoli F, Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Taffurelli M, Marrano D, Baldini N: Clone heterogeneity in diploid and aneuploid breast carcinomas as detected by FISH. Cytometry. 2001, 46: 50-56. 10.1002/1097-0320(20010215)46:1<50::AID-CYTO1037>3.0.CO;2-T.

Zhang L, Cui X, Schmitt K, Hubert R, Navidi W, Arnheim N: Whole genome amplification from a single cell: implications for genetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992, 89: 5847-5851. 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5847.

Lage JM, Leamon JH, Pejovic T, Hamann S, Lacey M, Dillon D, Segraves R, Vossbrinck B, González A, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Costa J, Lizardi PM: Whole genome analysis of genetic alterations in small DNA samples using hyperbranched strand displacement amplification and array-CGH. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 294-307. 10.1101/gr.377203.

Dean FB, Hosono S, Fang L, Wu X, Faruqi AF, Bray-Ward P, Sun Z, Zong Q, Du Y, Du J, Driscoll M, Song W, Kingsmore SF, Egholm M, Lasken RS: Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 5261-5266. 10.1073/pnas.082089499.

Klein CA, Schmidt-Kittler O, Schardt JA, Pantel K, Speicher MR, Riethmüller G: Comparative genomic hybridization, loss of heterozygosity, and DNA sequence analysis of single cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 4494-4499. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4494.

Ivakhno S, Royce T, Cox AJ, Evers DJ, Cheetham RK, Tavaré S: CNAseg - a novel framework for identification of copy number changes in cancer from second-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26: 3051-3058. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq587.

Alkan C, Kidd JM, Marques-Bonet T, Aksay G, Antonacci F, Hormozdiari F, Kitzman JO, Baker C, Malig M, Mutlu O, Sahinalp SC, Gibbs RA, Eichler EE: Personalized copy number and segmental duplication maps using next-generation sequencing. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 1061-1067. 10.1038/ng.437.

Chiang DY, Getz G, Jaffe DB, O’Kelly MJ, Zhao X, Carter SL, Russ C, Nusbaum C, Meyerson M, Lander ES: High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nat Methods. 2009, 6: 99-103. 10.1038/nmeth.1276.

Wood HM, Belvedere O, Conway C, Daly C, Chalkley R, Bickerdike M, McKinley C, Egan P, Ross L, Hayward B, Morgan J, Davidson L, MacLennan K, Ong TK, Papagiannopoulos K, Cook I, Adams DJ, Taylor GR, Rabbitts P: Using next-generation sequencing for high resolution multiplex analysis of copy number variation from nanogram quantities of DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38: e151-10.1093/nar/gkq510.

Yoon S, Xuan Z, Makarov V, Ye K, Sebat J: Sensitive and accurate detection of copy number variants using read depth of coverage. Genome Res. 2009, 19: 1586-1592. 10.1101/gr.092981.109.

Grubor V, Krasnitz A, Troge JE, Meth JL, Lakshmi B, Kendall JT, Yamrom B, Alex G, Pai D, Navin N, Hufnagel LA, Lee YH, Cook K, Allen SL, Rai KR, Damle RN, Calissano C, Chiorazzi N, Wigler M, Esposito D: Novel genomic alterations and clonal evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis (ROMA). Blood. 2009, 113: 1294-1303. 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158865.

Arriola E, Lambros MB, Jones C, Dexter T, Mackay A, Tan DS, Tamber N, Fenwick K, Ashworth A, Dowsett M, Reis-Filho JS: Evaluation of Phi29-based whole-genome amplification for microarray-based comparative genomic hybridisation. Lab Invest. 2007, 87: 75-83. 10.1038/labinvest.3700495.

Huang J, Pang J, Watanabe T, Ng HK, Ohgaki H: Whole genome amplification for array comparative genomic hybridization using DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded histological sections. J Mol Diagn. 2009, 11: 109-116. 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080143.

Schwartz S, Oren R, Ast G: Detection and removal of biases in the analysis of next-generation sequencing reads. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e16685-10.1371/journal.pone.0016685.

Talseth-Palmer BA, Bowden NA, Hill A, Meldrum C, Scott RJ: Whole genome amplification and its impact on CGH array profiles. BMC Res Notes. 2008, 1: 56-10.1186/1756-0500-1-56.

Hughes S, Lim G, Beheshti B, Bayani J, Marrano P, Huang A, Squire JA: Use of whole genome amplification and comparative genomic hybridisation to detect chromosomal copy number alterations in cell line material and tumour tissue. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004, 105: 18-24. 10.1159/000078004.

Lasken RS, Stockwell TB: Mechanism of chimera formation during the Multiple Displacement Amplification reaction. BMC Biotechnol. 2007, 7: 19-10.1186/1472-6750-7-19.

Szelinger S, Kurdoglu A, Craig DW: Bar-coded, multiplexed sequencing of targeted DNA regions using the Illumina Genome Analyzer. Methods Mol Biol. 2011, 700: 89-104. 10.1007/978-1-61737-954-3_7.

Erlich Y, Chang K, Gordon A, Ronen R, Navon O, Rooks M, Hannon GJ: DNA Sudoku - harnessing high-throughput sequencing for multiplexed specimen analysis. Genome Res. 2009, 19: 1243-1253. 10.1101/gr.092957.109.

Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Fisher E, Margolese R, Dimitrov N, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Deutsch M, Ore L, Mamounas E, Poller W, Kavanah M: Lumpectomy compared with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993, 328: 1581-1586. 10.1056/NEJM199306033282201.

Julien JP, Bijker N, Fentiman IS, Peterse JL, Delledonne V, Rouanet P, Avril A, Sylvester R, Mignolet F, Bartelink H, Van Dongen JA: Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet. 2000, 355: 528-533. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06341-2.

Kerlikowske K, Molinaro AM, Gauthier ML, Berman HK, Waldman F, Bennington J, Sanchez H, Jimenez C, Stewart K, Chew K, Ljung BM, Tlsty TD: Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010, 102: 627-637. 10.1093/jnci/djq101.

Fisher B, Land S, Mamounas E, Dignam J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N: Prevention of invasive breast cancer in women with ductal carcinoma in situ: an update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Semin Oncol. 2001, 28: 400-418. 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90133-2.

Kerlikowske K, Molinaro A, Cha I, Ljung BM, Ernster VL, Stewart K, Chew K, Moore DH, Waldman F: Characteristics associated with recurrence among women with ductal carcinoma in situ treated by lumpectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95: 1692-1702.

Allred DC, Wu Y, Mao S, Nagtegaal ID, Lee S, Perou CM, Mohsin SK, O’Connell P, Tsimelzon A, Medina D: Ductal carcinoma in situ and the emergence of diversity during breast cancer evolution. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 370-378. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1127.

Bidard FC, Mathiot C, Delaloge S, Brain E, Giachetti S, de Cremoux P, Marty M, Pierga JY: Single circulating tumor cell detection and overall survival in nonmetastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010, 21: 729-733. 10.1093/annonc/mdp391.

Rao C, Bui T, Connelly M, Doyle G, Karydis I, Middleton MR, Clack G, Malone M, Coumans FA, Terstappen LW: Circulating melanoma cells and survival in metastatic melanoma. Int J Oncol. 2011, 38: 755-760.

Vincent-Salomon A, Bidard FC, Pierga JY: Bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer: review of detection methods, prognostic impact and biological issues. J Clin Pathol. 2008, 61: 570-576. 10.1136/jcp.2007.046649.

Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Ryan P, Balis UJ, Tompkins RG, Haber DA, Toner M: Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007, 450: 1235-1239. 10.1038/nature06385.

Terstappen LW, Rao C, Gross S, Kotelnikov V, Racilla E, Uhr J, Weiss A: Flow cytometry - principles and feasibility in transfusion medicine. Enumeration of epithelial derived tumor cells in peripheral blood. Vox Sang. 1998, 74 (Suppl 2): 269-274.

Garcia JA, Rosenberg JE, Weinberg V, Scott J, Frohlich M, Park JW, Small EJ: Evaluation and significance of circulating epithelial cells in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007, 99: 519-524. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06659.x.

Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW, Terstappen LW: Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10: 6897-6904. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378.

Stathopoulos EN, Sanidas E, Kafousi M, Mavroudis D, Askoxylakis J, Bozionelou V, Perraki M, Tsiftsis D, Georgoulias V: Detection of CK-19 mRNA-positive cells in the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients with histologically and immunohistochemically negative axillary lymph nodes. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 240-246. 10.1093/annonc/mdi043.

Xenidis N, Perraki M, Kafousi M, Apostolaki S, Bolonaki I, Stathopoulou A, Kalbakis K, Androulakis N, Kouroussis C, Pallis T, Christophylakis C, Argyraki K, Lianidou ES, Stathopoulos S, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D: Predictive and prognostic value of peripheral blood cytokeratin-19 mRNA-positive cells detected by real-time polymerase chain reaction in node-negative breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 3756-3762. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5948.

Ignatiadis M, Kallergi G, Ntoulia M, Perraki M, Apostolaki S, Kafousi M, Chlouverakis G, Stathopoulos E, Lianidou E, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D: Prognostic value of the molecular detection of circulating tumor cells using a multimarker reverse transcription-PCR assay for cytokeratin 19, mammaglobin A, and HER2 in early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 2593-2600. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4758.

Gerges N, Rak J, Jabado N: New technologies for the detection of circulating tumour cells. Br Med Bull. 2010, 94: 49-64. 10.1093/bmb/ldq011.

Tosoian J, Loeb S: PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. Scientific World Journal. 2010, 10: 1919-1931.

Walsh CS, Ogawa S, Karahashi H, Scoles DR, Pavelka JC, Tran H, Miller CW, Kawamata N, Ginther C, Dering J, Sanada M, Nannya Y, Slamon DJ, Koeffler HP, Karlan BY: ERCC5 is a novel biomarker of ovarian cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 2952-2958. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5806.

Anastasi E, Marchei GG, Viggiani V, Gennarini G, Frati L, Reale MG: HE4: a new potential early biomarker for the recurrence of ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2010, 31: 113-119. 10.1007/s13277-009-0015-y.

Hirsch FR, Ottesen G, Pødenphant J, Olsen J: Tumor heterogeneity in lung cancer based on light microscopic features. A retrospective study of a consecutive series of 200 patients, treated surgically. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1983, 402: 147-153. 10.1007/BF00695056.

Fitzgerald PJ: Homogeneity and heterogeneity in pancreas cancer: presence of predominant and minor morphological types and implications. Int J Pancreatol. 1986, 1: 91-94.

van der Poel HG, Oosterhof GO, Schaafsma HE, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA: Intratumoral nuclear morphologic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Urology. 1997, 49: 652-657. 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00557-2.

Krüger S, Thorns C, Böhle A, Feller AC: Prognostic significance of a grading system considering tumor heterogeneity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003, 35: 169-173.

Park SY, Gönen M, Kim HJ, Michor F, Polyak K: Cellular and genetic diversity in the progression of in situ human breast carcinomas to an invasive phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2010, 120: 636-644. 10.1172/JCI40724.

Roka S, Fiegl M, Zojer N, Filipits M, Schuster R, Steiner B, Jakesz R, Huber H, Drach J: Aneuploidy of chromosome 8 as detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization is a recurrent finding in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998, 48: 125-133. 10.1023/A:1005937305102.

Mora J, Cheung NK, Gerald WL: Genetic heterogeneity and clonal evolution in neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2001, 85: 182-189. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1849.

Zojer N, Fiegl M, Müllauer L, Chott A, Roka S, Ackermann J, Raderer M, Kaufmann H, Reiner A, Huber H, Drach J: Chromosomal imbalances in primary and metastatic pancreatic carcinoma as detected by interphase cytogenetics: basic findings and clinical aspects. Br J Cancer. 1998, 77: 1337-1342. 10.1038/bjc.1998.223.

Pantou D, Rizou H, Tsarouha H, Pouli A, Papanastasiou K, Stamatellou M, Trangas T, Pandis N, Bardi G: Cytogenetic manifestations of multiple myeloma heterogeneity. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005, 42: 44-57. 10.1002/gcc.20114.

Maley CC, Galipeau PC, Finley JC, Wongsurawat VJ, Li X, Sanchez CA, Paulson TG, Blount PL, Risques RA, Rabinovitch PS, Reid BJ: Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 468-473. 10.1038/ng1768.

Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA: Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010, 467: 1114-1117. 10.1038/nature09515.

Aubele M, Mattis A, Zitzelsberger H, Walch A, Kremer M, Hutzler P, Höfler H, Werner M: Intratumoral heterogeneity in breast carcinoma revealed by laser-microdissection and comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999, 110: 94-102. 10.1016/S0165-4608(98)00205-2.

Cooke SL, Temple J, Macarthur S, Zahra MA, Tan LT, Crawford RA, Ng CK, Jimenez-Linan M, Sala E, Brenton JD: Intra-tumour genetic heterogeneity and poor chemoradiotherapy response in cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011, 104: 361-368. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605971.

Shah SP, Morin RD, Khattra J, Prentice L, Pugh T, Burleigh A, Delaney A, Gelmon K, Guliany R, Senz J, Steidl C, Holt RA, Jones S, Sun M, Leung G, Moore R, Severson T, Taylor GA, Teschendorff AE, Tse K, Turashvili G, Varhol R, Warren RL, Watson P, Zhao Y, Caldas C, Huntsman D, Hirst M, Marra MA, Aparicio S: Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2009, 461: 809-813. 10.1038/nature08489.

Ding L, Ellis MJ, Li S, Larson DE, Chen K, Wallis JW, Harris CC, McLellan MD, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Abbott RM, Hoog J, Dooling DJ, Koboldt DC, Schmidt H, Kalicki J, Zhang Q, Chen L, Lin L, Wendl MC, McMichael JF, Magrini VJ, Cook L, McGrath SD, Vickery TL, Appelbaum E, Deschryver K, Davies S, Guintoli T, Lin L, et al: Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature. 2010, 464: 999-1005. 10.1038/nature08989.

Cole KA, Krizman DB, Emmert-Buck MR: The genetics of cancer - a 3D model. Nat Genet. 1999, 21 (1 Suppl): 38-41.

Bachtiary B, Boutros PC, Pintilie M, Shi W, Bastianutto C, Li JH, Schwock J, Zhang W, Penn LZ, Jurisica I, Fyles A, Liu FF: Gene expression profiling in cervical cancer: an exploration of intratumor heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 5632-5640. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0357.

Johann DJ, Rodriguez-Canales J, Mukherjee S, Prieto DA, Hanson JC, Emmert-Buck M, Blonder J: Approaching solid tumor heterogeneity on a cellular basis by tissue proteomics using laser capture microdissection and biological mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2009, 8: 2310-2318. 10.1021/pr8009403.

Wemmert S, Romeike BF, Ketter R, Steudel WI, Zang KD, Urbschat S: Intratumoral genetic heterogeneity in pilocytic astrocytomas revealed by CGH-analysis of microdissected tumor cells and FISH on tumor tissue sections. Int J Oncol. 2006, 28: 353-360.

Ottesen AM, Larsen J, Gerdes T, Larsen JK, Lundsteen C, Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E: Cytogenetic investigation of testicular carcinoma in situ and early seminoma by high-resolution comparative genomic hybridization analysis of subpopulations flow sorted according to DNA content. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004, 149: 89-97. 10.1016/S0165-4608(03)00281-4.

Kobayashi M, Ishida H, Shindo T, Niwa S, Kino M, Kawamura K, Kamiya N, Imamoto T, Suzuki H, Hirokawa Y, Shiraishi T, Tanizawa T, Nakatani Y, Ichikawa T: Molecular analysis of multifocal prostate cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Prostate. 2008, 68: 1715-1724. 10.1002/pros.20832.

Oakman C, Santarpia L, Di Leo A: Breast cancer assessment tools and optimizing adjuvant therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010, 7: 725-732. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.170.

Gerlinger M, Swanton C: How Darwinian models inform therapeutic failure initiated by clonal heterogeneity in cancer medicine. Br J Cancer. 2010, 103: 1139-1143. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605912.

Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC: Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006, 6: 924-935. 10.1038/nrc2013.

Cooke SL, Ng CK, Melnyk N, Garcia MJ, Hardcastle T, Temple J, Langdon S, Huntsman D, Brenton JD: Genomic analysis of genetic heterogeneity and evolution in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010, 29: 4905-4913. 10.1038/onc.2010.245.

Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, Varela I, Pleasance ED, Simpson JT, Stebbings LA, Leroy C, Edkins S, Mudie LJ, Greenman CD, Jia M, Latimer C, Teague JW, Lau KW, Burton J, Quail MA, Swerdlow H, Churcher C, Natrajan R, Sieuwerts AM, Martens JW, Silver DP, Langerød A, Russnes HE, Foekens JA, Reis-Filho JS, van’t Veer L, Richardson AL, Børresen-Dale AL, et al: Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009, 462: 1005-1010. 10.1038/nature08645.

Eid J, Fehr A, Gray J, Luong K, Lyle J, Otto G, Peluso P, Rank D, Baybayan P, Bettman B, Bibillo A, Bjornson K, Chaudhuri B, Christians F, Cicero R, Clark S, Dalal R, Dewinter A, Dixon J, Foquet M, Gaertner A, Hardenbol P, Heiner C, Hester K, Holden D, Kearns G, Kong X, Kuse R, Lacroix Y, Lin S, et al: Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science. 2009, 323: 133-138. 10.1126/science.1162986.

Teixeira MR, Pandis N, Bardi G, Andersen JA, Heim S: Karyotypic comparisons of multiple tumorous and macroscopically normal surrounding tissue samples from patients with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1996, 56: 855-859.

Acknowledgements

NN is funded by the Alice Kleberg Reynolds Foundation. JH and NN were supported by grants from the Department of the Army (W81XWH04-1-0477) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. We also thank Dr. Michael Wigler, Jude Kendall, Peter Andrews, Linda Rodgers, Jennifer Troge and member of the Wigler Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navin, N., Hicks, J. Future medical applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer. Genome Med 3, 31 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/gm247

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/gm247