Abstract

Introduction

We studied the diagnostic accuracy of bedside lung ultrasound (the presence of a comet-tail sign), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and clinical assessment (according to the modified Boston criteria) in differentiating heart failure (HF)-related acute dyspnea from pulmonary (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/asthma)-related acute dyspnea in the prehospital setting.

Methods

Our prospective study was performed at the Center for Emergency Medicine, Maribor, Slovenia, between July 2007 and April 2010. Two groups of patients were compared: a HF-related acute dyspnea group (n = 129) and a pulmonary (asthma/COPD)-related acute dyspnea group (n = 89). All patients underwent lung ultrasound examinations, along with basic laboratory testing, rapid NT-proBNP testing and chest X-rays.

Results

The ultrasound comet-tail sign has 100% sensitivity, 95% specificity, 100% negative predictive value (NPV) and 96% positive predictive value (PPV) for the diagnosis of HF. NT-proBNP (cutoff point 1,000 pg/mL) has 92% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 86% NPV and 90% PPV. The Boston modified criteria have 85% sensitivity, 86% specificity, 80% NPV and 90% PPV. In comparing the three methods, we found significant differences between ultrasound sign and (1) NT-proBNP (P < 0.05) and (2) Boston modified criteria (P < 0.05). The combination of ultrasound sign and NT-proBNP has 100% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% NPV and 100% PPV. With the use of ultrasound, we can exclude HF in patients with pulmonary-related dyspnea who have positive NT-proBNP (> 1,000 pg/mL) and a history of HF.

Conclusions

An ultrasound comet-tail sign alone or in combination with NT-proBNP has high diagnostic accuracy in differentiating acute HF-related from COPD/asthma-related causes of acute dyspnea in the prehospital emergency setting.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01235182.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute congestive heart failure (CHF) is one of the main causes of acute dyspnea encountered in prehospital emergency settings and is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1–3]. The early and correct diagnosis presents a significant clinical challenge and is of primary importance, as misdiagnosis can result in deleterious consequences to patients [4–6]. Rapid bedside tests, especially brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), help in determining the cause of acute dyspnea in the prehospital setting [2, 7]. Point-of-care bedside lung ultrasound has also become a useful method for diagnosing CHF [8]. The technique is based on the recognition and analysis of sonographic artefacts caused by the interaction of water-rich structures and air, called comet tails or B lines. When such artefacts are widely detected on anterolateral transthoracic lung scans, diffuse alveolar-interstitial syndrome can be diagnosed and the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), another important cause of acute dyspnea, can be ruled out. Lichtenstein et al.[9] first described comet-tail signs or B lines indicating interstitial pulmonary edema, and Lichtenstein and Mezière [10] described a systematic approach to lung ultrasound. Volpicelli et al.[11] proposed a simplified ultrasound approach to diagnosing the alveolar-interstitial syndrome at bedside. Liteplo et al.[12] combined emergency thoracic ultrasound and NT-proBNP to differentiate CHF from COPD in the emergency department.

The aim of our study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of bedside lung ultrasound (bilateral comet-tail sign or multiple vertical B lines, referred to as "lung rockets"), NT-proBNP and clinical assessment in differentiating heart failure (HF)-related acute dyspnea from pulmonary (COPD/asthma)-related acute dyspnea in the prehospital setting (that is, in the field).

Materials and methods

This prospective cohort study was performed in the prehospital emergency setting (Center for Emergency Medicine, Maribor, Slovenia) between July 2007 and April 2010. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Ministry of Health of Slovenia. During the period of the study, 248 consecutive patients with acute dyspnea were treated by emergency teams (emergency physician, registered nurse and medical technician/driver in an ambulance or at the prehospital emergency medical center). After prehospital care, all patients were admitted (for clinical reasons and/or because they fit the study design criteria) to the University Clinical Center Maribor and followed until discharge.

The inclusion criterion for the study was shortness of breath as the primary complaint (defined as either the sudden onset of dyspnea without history of chronic dyspnea or an increase in the severity of chronic dyspnea). Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, history of renal insufficiency, trauma, severe coronary ischemia (unless patient's predominant presentation was dyspnea) and other causes of dyspnea, comprising pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, carcinoma, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, intoxication (drugs), anaphylactic reactions, upper airway obstruction, bronchial stenosis and gastroesophageal reflux disorder, according to the history, clinical status and additional laboratory tests available in the prehospital setting (D-dimer, troponin, C-reactive protein). Among 248 patients, 218 met the criteria for inclusion in the study. The distribution of all patients is shown in Figure 1.

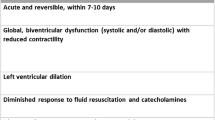

After enrollment, patients' demographic characteristics, symptoms and signs, medical histories, medication use, chest X-rays and standard blood test results (after admission to the hospital) were recorded. Our protocol for clinical assessment of HF-related acute dyspnea (the prehospital clinical assessment of HF) was designed according to the Boston criteria [6] and the Framingham criteria [13] for HF and was explained in our previous study [2] (Table 1). For additional evaluation of patients with suspected obstructive causes of dyspnea, we included criteria for clinical assessment of severe asthma [14, 15] and COPD exacerbation [16] with the value of modified Boston criteria for HF being ≤ 5.

The final hospital diagnosis of HF-related acute dyspnea and pulmonary-related acute dyspnea (the hospital reference standard for HF and pulmonary diseases: asthma/COPD) was confirmed by cardiologists and/or intensive care physicians in the University Clinical Center Maribor using the reference standard definition for HF and pulmonary diseases in accordance with the previously cited instruments, including chest X-ray, echocardiographic examination, cardiac functional assessment (exercise test), pulmonary function test, complete blood count, biochemistry and invasive investigation or angiography [6, 13–16].

According to these criteria, identification of independent predictors for final diagnosis of acute dyspnea was performed by examination of 27 variables (Table 2). Central venous pressure (CVP) in the field was assessed by the visualization of the external jugular vein, which correlates well with catheter-measured CVP [17].

During initial evaluation (before application of medicines), a 5-mL sample of blood was collected into a tube containing edetate calcium disodium for blinded measurement of NT-proBNP. The level of NT-proBNP was measured using a portable Cardiac Reader device (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and recorded according to the special protocol. The test was finished within 15 minutes [2, 18].

The bedside thoracic ultrasound was performed according to the protocol described by Cardinale et al.[8], Volpicelli et al.[11] and Liteplo et al.[12], in which eight zones of the lungs were scanned (two anterior and two lateral zones on each side of thorax). We used a portable ultrasound machine manufactured by SonoSite (SonoSite, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA). The 10 emergency physicians were included in the investigations, and they had to identify the presence or absence of three or more B lines in each of the eight zones. B lines (comet-tail signs) are hyperechoic reverberation artefacts that originate at the pleural line and extend vertically to the bottom of the screen. A positive ultrasound examination according to the definition of Cardinale et al.[8] and Volpicelli et al.[11] requires two or more positive zones bilaterally of eight zones measured. All emergency physicians who participated in our study had attended the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical UltraSound provider course. The length of the examination was always under 1 minute.

NT-proBNP measurements and ultrasound examinations were performed immediately after the arrival of the patient at the emergency department but before application of medication, thus our results were not altered by treatment. The raters who made the diagnosis (prehospital emergency physicians in the prehospital setting, internists at admission to the hospital and cardiologists and/or intensive care physicians at discharge from the hospital with the final diagnosis) were blinded to the results of NT-proBNP. In addition, the investigators of NT-proBNP did not collaborate in making the final diagnosis. On the other side, prehospital emergency physicians were not blinded to the ultrasound findings, because bedside lung ultrasound represents the routine method for assessment of acute dyspnea in our prehospital emergency unit. To avoid bias, the ultrasound findings were recorded by the emergency physicians but did not affect the diagnosis. The raters who made the diagnosis in the hospital were blinded to the findings of prehospital ultrasound. To our knowledge, no previous study has compared the diagnostic utility of ultrasound examination and NT-proBNP in a prehospital setting.

Statistical analysis

Univariate comparisons were made by using the χ2 test for categorical variables and an unpaired t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution (age, pulse rate, partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide, NT-proBNP, arterial oxygen saturation and modified Boston criteria for HF). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) were calculated to examine the risk of acute HF (adjusted using multiple logistic regression). Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV), positive likelihood ratio (LR+) and negative likelihood ratio (LR-) were estimated for clinical assessment (based on the modified Boston criteria), NT-proBNP, ultrasound examination and a combination of ultrasound with NT-proBNP. The comparison of these four methods was done by using the χ2 test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The area under the receiver-operating curve (AUROC) was also used to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the four methods in differentiating HF-related acute dyspnea from pulmonary-related acute dyspnea. Single areas were calculated and compared with univariate Z-score testing. We compared the areas under different curves using the technique proposed by Hanley and McNeil [19] and Jannuzzi et al.[20]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). AUROC analysis was performed using Analyze-It software (Leeds, UK).

Consent

The authors confirm that all patients gave their consent for study participation and potential publication of the study results.

Results

During the period of the study, 248 consecutive patients with acute dyspnea were treated by emergency teams (129 patients with HF-related acute dyspnea and 89 patients with pulmonary-related acute dyspnea). Thirty patients were excluded from the study. The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients are presented in Table 2. The group of patients with acute HF was significantly older (mean ages 70.9 ± 11.7 years versus 52.3 ± 15.3 years; P = 0.001). The feasibility of ultrasound examination in the prehospital setting was 100%, and the duration of the examination was always less than 1 minute. For the identification of independent predictors for the final diagnosis of acute dyspnea, we examined 24 variables (variables with P < 0.05 on the basis of univariate analysis) in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Ten variables remained significant after analysis (Table 3). Evidently, there is big difference in ORs between ultrasound examinations (mean OR, 53.7; 95% CI, 28.6 to 83.5) and NT-proBNP (mean OR, 14.3; 95% CI, 8.1 to 29.4) and other variables. The ultrasound examination was the strongest predictor of acute HF.

In Table 4, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, LR+, LR- and AUROC values are presented for ultrasound examinations (cutoff point: two or more positive zones bilaterally), modified Boston criteria (cutoff point: total 8 points), NT-proBNP (cutoff point: 1,000 pg/mL) and a combination of ultrasound examination with NT-proBNP. In comparing the methods, we found significant differences between ultrasound signs versus NT-proBNP (P < 0.05) and ultrasound signs versus modified Boston criteria (P < 0.05). All 11 patients for whom false-positive results were found using the NT-proBNP method had values higher than 1,000 pg/mL (mean, 1,564 ± 651.3; range, 1,200 to 2,750 pg/mL) and a history of HF. In all of these 11 patients, we confirmed the absence of comet-tail signs. With ultrasound, we can exclude HF in pulmonary-related dyspneic patients with positive NT-proBNP results and a history of HF. All five patients for whom false-positive results were found using the ultrasound method had NT-proBNP values less than 1,000 pg/mL (mean, 541.3 ± 265.1) and a history of COPD/asthma. With the value of NT-proBNP, we can exclude HF in ultrasound-positive pulmonary-related dyspneic patients.

The combination of ultrasound examination and NT-proBNP was statistically significantly different from the use of single methods. It had values of 100% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% NPV, 100% PPV, LR+ infinite, LR- zero, and AUROC 0.99.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that ultrasound examination was the best single method for confirming the diagnosis of acute HF in the prehospital setting. Compared with clinical assessment using modified Boston criteria and NT-proBNP testing, lung ultrasound had a significantly better AUROC with regard to diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the combination of ultrasound examination and rapid bedside NT-proBNP testing proved to be an even more reliable method for the identification of acute HF and its differentiation from COPD/asthma-related causes of acute dyspnea.

Acute dyspnea is one of the most common conditions encountered in emergency care settings. Correct diagnosis and treatment are of primary importance, as misdiagnosis can result in deleterious consequences for patients. Timely differentiation of HF from other causes of acute dyspnea (especially in cases of COPD/asthma comorbidity) may be difficult. Physical examination, chest radiography, electrocardiography, and standard biological tests often fail to accurately differentiate HF from pulmonary causes of dyspnea [2, 4–6]. Rapid NT-proBNP testing has been confirmed as a highly sensitive and specific biomarker for the diagnosis or exclusion of acute HF in emergency care settings [20, 21] and may produce improvements in the prehospital management of patients with dyspnea [7]. The reliability of transthoracic lung ultrasound in differentiating acute dyspnea has been confirmed in some previous studies by Lichtenstein et al.[9, 10], Cardinale et al.[8] and Volpicelli et al.[11]. The comet-tail sign (B lines) has been proposed as a simple, non-time-consuming sonographic sign of pulmonary congestion and can be obtained at bedside (also with portable echocardiographic equipment) [22]. Agricolla et al.[23] studied the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound in diagnosing intersitial pulmonary edema and found significant positive linear correlations between comet-tail signs and chest radiography, wedge pressure and extravascular lung water quantified by the indicator dilution method. Liteplo et al.[12] reported that lung ultrasound could be used alone or could provide additional predictive power to NT-proBNP in the immediate evaluation of dyspneic patients presenting to the emergency department.

The data from our study (similarly to the study by Liteplo et al.[12]) suggest that NT-proBNP and ultrasound examinations provide complementary diagnostic information which may be useful in the early evaluation of HF in the prehospital setting (that is, in the field). The combination of these two methods has an excellent statistical value: 100% sensitivity, specificity, NPV and PPV; 99% AUROC; LR+ infinite; and LR- zero. To our knowledge, no previous study has specifically compared the utility of lung ultrasound and NT-proBNP in the out-of-hospital setting, as researchers have focused on the patients in emergency departments and intensive care units. Zechner et al.[24] presented two cases of dyspneic patients in whom prehospital lung ultrasound helped to distinguish pulmonary edema from acute exacerbation of COPD and suggested the application of ultrasound in the field.

Prehospital emergency physicians offer the earliest treatment of acute dyspnea, which is performed as soon as clinically possible after the event. On the basis of clinical judgment alone, it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish cardiac from pulmonary causes of dyspnea. If prehospital physicians have the tools of rapid NT-proBNP testing and ultrasound at their disposal, the diagnostic dilemmas in differentiating causes of dyspnea are reduced and the treatment possibilities in clinically obscure cases are mainly improved.

Ultrasound is currently the only imaging method that can be used in the field. It offers an opportunity to extend and improve out-of-hospital diagnostic possibilities and is useful for prehospital emergency physicians with additional knowledge of point-of-care ultrasound diagnostics. Under special circumstances, it may be used by well-educated paramedics [25, 26]. The application of the Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergency Protocol [27] in the field presents an important moment of transition from in-hospital intensive care medicine to out-of-hospital emergency medicine in the diagnostics and treatment of acute dyspnea. In systems such as Slovenia's, where there are medical doctors in prehospital settings, this methodology could prevent transport and hospitalization. In our next study, we intend to test the efficacy of this methodology for preventing hospitalization and improving cost and time efficiency by using ultrasound in patients with dyspnea. On the basis of the presented data, we have developed a simple algorithm for using ultrasound in patients with dyspnea. If the ultrasound does not show B lines, then the diagnosis is COPD/asthma and further evaluation are unnecessary. If there are B lines, then NT-pro-BNP should be measured. If NT-proBNP is positive, the diagnosis is acute HF, and if NT-proBNP is negative, the diagnosis is COPD/asthma. This algorithm could be a powerful tool for emergency care providers, but further investigation (a larger, multicenter study) is needed to validate the utility of this algorithm in the prehospital setting.

This study has methodological limitations. In our analysis, we included only patients with primary HF or COPD/asthma diagnosed in the field, and this limitation decreases the generalizability of this study to other causes of acute dyspnea in the prehospital setting. The primary aim of our study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of bedside lung ultrasound and NT-proBNP in differentiating HF-related acute dyspnea from COPD/asthma-related acute dyspnea in prehospital settings.

Conclusions

Ultrasound examination of the lungs alone or in combination with NT-proBNP testing has high diagnostic accuracy in differentiating acute HF-related from COPD/asthma-related causes of acute dyspnea in prehospital emergency settings. The combination of these two methods helps to improve the diagnostic and treatment possibilities in clinically obscure cases of acute dyspnea in the earliest phases of their appearance. Both methods are simple, non-time-consuming and can be used at bedside or in the field.

Key messages

-

Diagnosis of severe, acute dyspnea in the prehospital arena and/or the emergency department can be challenging, but lung ultrasound is proving to be an accurate new diagnostic tool by itself or in combination with other diagnostic modalities.

-

Pulmonary edema gives specific, diffusely vertical artefact line (B lines and comet-tail signs) patterns on ultrasound, unlike the results found in patients with obstructive diseases or pulmonary emboli (generally A lines in both cases).

-

The question remains how well specific patterns of diffuse B lines on ultrasound scans correlate with levels of NT-pro-BNP and how they help in making the correct diagnosis.

-

In our study, the combination of ultrasound examination and NT-proBNP had 100% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% NPV and 100% PPV for differentiating heart failure as the cause of acute dyspnea compared to pulmonary causes in the prehospital setting.

-

Both ultrasound examinations and NT-pro-BNP point-of-care assays are quick, accurate and feasible, with high diagnostic accuracy, in the prehospital arena.

Abbreviations

- AUROC:

-

area under the receiver-operating curve

- BNP:

-

brain natriuretic peptide

- CHF:

-

congestive heart failure

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVP:

-

central venous pressure

- HF:

-

heart failure

- LR+:

-

positive likelihood ratio

- LR-:

-

negative likelihood ratio

- NPV:

-

negative predictive value

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- PetCO2:

-

partial pressure of end-tidal carbon dioxide

- PPV:

-

positive predictive value.

References

Ray P, Delerme S, Jourdain P, Chenevier-Gobeaux C: Differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea: the value of B natriuretic peptides in the emergency department. QJM 2008, 101: 831-843. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn080

Klemen P, Golub M, Grmec S: Combination of quantitative capnometry, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, and clinical assessment in differentiating acute heart filure from pulmonary disease as cause of acute dyspnea in prehospital emergency setting: study of diagnostic accuracy. Croat Med J 2009, 50: 133-142. 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.133

Steinhart B, Thorpe KE, Bayoumi AM, Moe G, Januzzi JL Jr, Mazer CD: Improving the diagnosis heart failure using a validated prediction model. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009, 54: 1515-1521. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.065

Michota FA Jr, Amin A: Bridging the gap between evidence and practice in acute decompensated heart failure management. J Hosp Med 2008,3(6 Suppl):S7-S15.

Mosesso VN Jr, Dunford J, Blackwell T, Griswell JK: Prehospital therapy for acute congestive heart failure:state of the rat. Prehosp Emerg Care 2003, 7: 13-23. 10.1080/10903120390937049

Remes J, Miettinen H, Reunanen A, Pyörälä K: Validity of clinical diagnosis of heart failure in primary health care. Eur Heart J 1991, 12: 315-321.

Teboul A, Gaffinel A, Meune C, Greffet A, Sauval P, Carli P: Management of caute dyspnea:use and feasibility of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) assay in the prehospital setting. Resuscitation 2004, 61: 91-96. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.12.005

Cardinale L, Volpicelli G, Binello F, Garofalo G, Priola SM, Veltri A, Fava C: Clinical application on lung ultrasound in patients with acute dyspnea:differential diagnosis between cardiogenic and pulmonary causes. Radiol Med 2009, 114: 1053-1064. 10.1007/s11547-009-0451-1

Lichtenstein D, Mezière GA, Biderman P, Gepner A, Barre O: The comet-tail artifact: an ultrasound sign of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997, 156: 1640-1646.

Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA: Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest 2008, 134: 117-125. 10.1378/chest.07-2800

Volpicelli G, Mussa A, Garofalo G, Cardinale L, Casoli G, Perotto F, Fava C, Francisco M: Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2006, 24: 689-696. 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.02.013

Liteplo AS, Marill KA, Villen T, Miller RM, Murray AF, Croft PE, Capp R, Noble VE: Emergency Thoracic Ultrasound in the Differentiation of the Etiology of shortness of Breath (ETUDES): sonographic B-lines and N-terminal Pro-brain-type Natriuretic Peptide in Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure. Acad Emerg Med 2009, 16: 201-210. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00347.x

McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB: The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1971, 285: 1441-1446. 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601

Papiris S, Kotanidou A, Malagari K, Roussos C: Clinical review: severe asthma. Crit Care 2002, 6: 30-44. 10.1186/cc1451

Chung KF, Godard P, Adelroth E, Ayres J, Barnes N, Barnes P, Bel E, Burney P, Chanez P, Connett G, Corrigan C, de Blic J, Fabbri L, Holgate ST, Ind P, Joos G, Kerstjens H, Leuenberger P, Lofdahl CG, McKenzie S, Magnussen H, Postma D, Saetta M, Salmeron S, Sterk P: Difficult/therapy-resistant asthma: the need for an integrated approach to define clinical phenotypes, evaluate risk factors, understand patophysiology and find novel therapies. ERS Task Force on Difficult/Therpy-Resistant Asthma. European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 1999, 13: 1198-1208.

Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS, GOLD Scientific Committee: Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLB/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163: 1256-1276.

McGee SR: Physical examination of venous pressure:a critical review. Am Heart J 1998, 136: 10-18. 10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70175-9

Baggish AL, Siebert U, Lainchbury JG, Cameron R, Anwaruddin S, Chen AA, Krauser DG, Tung R, Brown DF, Richards AM, Januzzi JL: A validated clinical and biochemical score for the diagnosis of acute heart failure:the ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) Acute Heart Failure Score. Am Heart J 2006, 151: 48-54. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.031

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983, 148: 839-843.

Januzzi JL Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, Baggish AL, Chen AA, Krauser DG, Tung R, Cameron R, Nagurney JT, Chae CU, Lloyd-Jones DM, Brown DF, Foran-Melanson S, Sluss PM, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Lewandrowski KB: The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol 2005, 95: 948-954. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.032

Januzzi JL Jr, Chen-Tournoux AA, Moe G: Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing for the diagnosis or exclusion of heart failure in patients with acute symptoms. Am J Cardiol 2008, 101: 29-38. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.017

Jambrik Z, Monti S, Coppola V, Agricola E, Mottola G, Miniati M, Picano E: Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. Am J Cardiol 2005, 96: 322-323.

Agricola E, Bove T, Oppizzi M, Marino G, Zangrillo A, Margonato A, Picano E: "Ultrasound comet-tail images": a marker of pulmonary edema: a marker of pulmonary edema:a comparative study with wedge pressure and extravascular lung water. Chest 2005, 127: 1690-1695. 10.1378/chest.127.5.1690

Zechner PM, Aichinger G, Rigaud M, Wildner G, Prause G: Prehospital lung ultrasound in the distinction between pulmonary edema and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Emerg Med 2010, 28: 389.e1-389.e2. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.07.021

Brooke M, Walton J, Scutt D: Paramedic application of ultrasound in the management of patients in the prehospital setting: a review of the literature. Emerg Med J 2010, 27: 702-707. 10.1136/emj.2010.094219

Heegaard W, Hildebrandt D, Spear D, Chason K, Nelson B, Ho J: Prehospital ultrasound by paramedics: results of field trial. Acad Emerg Med 2010, 17: 624-630. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00755.x

Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA: Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Am J Emerg Med 2006, 24: 689-696. 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.02.013

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted within the course of our regular work at the Center for Emergency Medicine in Maribor, Slovenia, with no extra funding in any form.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PG participated in the design of the study and collected and interpreted the data. KP participated in the design of the study, collected the data and wrote a final version of the manuscript. SM collected the data and participated in the coordination of the study. GŠ designed the study, participated in the data collection, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc10511.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Prosen, G., Klemen, P., Strnad, M. et al. Combination of lung ultrasound (a comet-tail sign) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in differentiating acute heart failure from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma as cause of acute dyspnea in prehospital emergency setting. Crit Care 15, R114 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10140

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10140