Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to determine whether, as in osteoarthritis, increased levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) are present in the synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic cartilage defects and whether this IL-6 affects cartilage regeneration as well as the cartilage in the degenerated knee.

Methods

IL-6 concentrations were determined by ELISA in synovial fluid and in conditioned media of chondrocytes regenerating cartilage. Chondrocytes were obtained from donors with symptomatic cartilage defects, healthy and osteoarthritic donors. The effect of IL-6 on cartilage regeneration and on metabolism of the resident cartilage in the knee was studied by both inhibition of endogenous IL-6 and addition of IL-6, in a regeneration model and in osteoarthritic explants in the presence of synovial fluid, respectively. Readout parameters were DNA and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content and release. Differences between controls and IL-6 blocked or supplemented samples were determined by univariate analysis of variance using a randomized block design.

Results

Synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic cartilage defects contained more IL-6 than synovial fluid of healthy donors (P = 0.001) and did not differ from osteoarthritic donors. IL-6 production of osteoarthritic chondrocytes during cartilage regeneration was higher than that of healthy and defect chondrocytes (P < 0.001). Adding IL-6 increased GAG production by healthy chondrocytes and decreased GAG release by osteoarthritic chondrocytes (P < 0.05). Inhibition of IL-6 present in osteoarthritic synovial fluid showed a trend towards decreased GAG content of the explants (P = 0.06).

Conclusions

Our results support a modest anabolic role for IL-6 in cartilage matrix production. Targeting multiple cytokines, including IL-6, may be effective in improving cartilage repair in symptomatic cartilage defects and osteoarthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cytokines are thought to play an important role in articular cartilage degeneration [1]. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) are known to have pivotal roles in its pathophysiology [2]. In addition to IL-1 and TNF-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6) has been demonstrated to play a role in cartilage degeneration in RA. In mice models of RA, cartilage destruction was shown to be dependent on IL-6 [3, 4]. Furthermore, tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor, now has an established role in the treatment of RA [5]. Besides efficacy in the amelioration of clinical signs and symptoms, tocilizumab has also been demonstrated to reduce joint space narrowing and levels of cartilage degradation biomarkers [6–8].

Although not as pronounced as in RA, mild and intermittent inflammation is frequently observed in symptomatic focal cartilage lesions, a condition thought to predispose to the development of osteoarthritis (OA), and in OA. Elevated concentrations of inflammatory mediators, including IL-6, have been found in the serum and synovial fluid of OA patients [9–16] and correlated to radiographic knee OA [17, 18]. However, the presence of IL-6 in joints with symptomatic cartilage defects has not been evaluated until now. In other joint injuries known to predispose to OA, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries [19–21] and meniscal tears [12, 22], increased levels of IL-6 have been detected in the synovial fluid. High levels of intra-articular inflammatory cytokines may, in addition to causing degeneration, also hamper tissue regeneration as cartilage repair is affected by the composition of the synovial fluid [23–25].

In OA most of the IL-6 present in the knee originates from the synovium [26]. However, chondrocytes in culture are capable of producing IL-6, albeit at low levels under most conditions [27–29]. Various stimuli, such as inflammatory molecules [30, 31] and binding of (fragmented) matrix components, which bind through discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2) [32, 33], have been reported to induce IL-6 synthesis, and these mechanisms are also proposed to play a role in OA. Chondrocytes can be stimulated by IL-6 either by binding directly to the gp80 receptor or, more commonly, through trans-signalling, in which IL-6 binds first to the soluble IL-6 receptor α (IL-6Rα) in the synovial fluid, and then forms a heterodimeric association with the membrane-bound gp130 receptor [34].

Despite its possible role in OA, studies investigating the role of IL-6 in OA models have provided inconsistent results. In vitro stimulation of chondrocytes with IL-6 has revealed anabolic effects, such as up-regulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) [35] and type II collagen [36], as well as catabolic effects, such as down-regulation of cartilage matrix genes [37, 38], inhibition of proteoglycan synthesis [39] and stimulation of aggrecanase production [40, 41]. In vivo models have also revealed both chondroprotective and chondrodegenerative properties of IL-6. A protective role of IL-6 in a spontaneous OA model was reported in aging male mice [42], but through both mechanically induced OA and OA induced by hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α), IL-6 was identified as the mediator of cartilage degradation [43]. However, many other studies have failed to demonstrate a direct effect of IL-6 on cartilage matrix metabolism [44–46]. One of the explanations for this lack of effect may lie in the simplified set-up of many studies in which IL-6 has been added, since the action of IL-6 may depend on other factors in the joint, in particular in the synovial fluid.

This study evaluated the presence of IL-6 in the synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic cartilage lesions and patients with late stage OA, its production by chondrocytes isolated from these patients, and its role in cartilage regeneration. In addition, to evaluate the possible effects of high levels of IL-6 in the synovial fluid on cartilage in the knee, we cultured OA cartilage explants in the presence of OA synovial fluid in which IL-6 was selectively inhibited.

Materials and methods

Synovial fluid and cartilage sample collection and cell isolation

Collection of all patient material was done according to the Medical Ethical regulations of the University Medical Center Utrecht and according to the guideline 'good use of redundant tissue for clinical research' constructed by the Dutch Federation of Medical Research Societies on collection of redundant tissue for research [47]. This study does not meet the definition of human subjects' research or require informed consent and anonymous use of redundant tissue for research purposes is part of the standard treatment agreement with patients in our hospital [48].

Macroscopically healthy articular cartilage (n = 6) and synovial fluid (n = 20, age 25 to 47, average 40 years) were obtained from donors without any history of major joint trauma, osteoarthritis or inflammatory joint disease and absence of cartilage defects and synovial inflammation upon inspection of the knee within 24 hours post-mortem. Consistently, only one knee per donor was used. Defect cartilage (n = 3) and synovial fluid (n = 22, age 20 to 48, average 33 years) were obtained from donors undergoing either microfracture or autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) for focal grade III and IV cartilage defects (only grade III cartilage was used for chondrocyte isolation). During those procedures, the cartilage defect was debrided to remove all cartilage remnants down to the subchondral bone and create a stable cartilage rim. The debrided cartilage was used for chondrocyte isolation. Chondrocytes from this location were recently shown to have good regenerative capacities compared to cells harvested from non-weight bearing cartilage normally used for ACI [49]. Of the 22 patients with symptomatic cartilage defects, one had an associated ACL injury and a history of partial menisectomy, another three had previously received partial menisectomies and one had undergone an ACL reconstruction. OA cartilage (n = 12) and synovial fluid (n = 27, age 53 to 81, average 70 years) were obtained from donors undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Synovial fluid was centrifuged at 13,000 g for two minutes to remove debris, and stored at -80°C until use or analysis. Glucocorticoids affecting cytokine production are not prescribed at our institution for patients with focal cartilage lesions and patients with end-stage OA eligible for total knee replacement.

Cartilage samples were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cut into small pieces and enzymatically digested overnight at 37°C in a 0.15% collagenase type II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Life Technologies, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) with penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL/100 μg/mL; Invitrogen, Life Technologies). After digestion, the cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), and the chondrocytes were spun down by 10 minutes centrifugation at 300 g.

Measurement of IL-6 levels

To determine the IL-6 levels in the synovial fluids of healthy, defect and OA donors and in the conditioned media of healthy, defect and OA chondrocytes during regeneration, a multiplex ELISA was performed as previously described [50, 51]. A total of 12 cytokines were measured of which IL-6 was most differentially regulated by healthy, defect and OA donors and hence chosen for further investigation. Briefly, specific antibodies (i.a. rat anti-human IL-6, MQ2-13A5; BD Biosciences) were coupled to carboxylated beads (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA). Recombinant human IL-6 (BD Biosciences, #550071) was used to make a standard curve. Synovial fluid samples were first treated with hyaluronidase (type IV-S, Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) at a concentration of 20 U/ml for 30 minutes at 37°C and then filtered by centrifuging through a polypropylene tube containing a 0.22 μm nylon membrane (Spin-X column; Corning, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Subsequently, the synovial fluid samples were diluted 1:2 with HPE-0.1375% Tween (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). To block possible interfering antibodies present in the synovial fluid, the samples were diluted with an equal volume of 10% (v/v) normal rat and mouse serum (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc., Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Medium samples were directly incubated with the coupled beads. After incubation with the appropriate biotinylated antibodies (i.a. biotinylated rat anti-human IL-6, MQ2-39C3; BD Biosciences), samples were thoroughly washed and incubated with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (BD Biosciences) for 10 minutes. After washing, the samples were measured and analyzed using the Bio-Plex suspension system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with Bio-Plex Manager software, version 3.0. The concentration of IL-6 in the media and synovial fluid was expressed as pg/mL using the standard curves. Results of specific ELISAs for determination of IL-6 levels have previously been shown to be comparable to multiplex ELISA for conditioned medium, plasma and knee lavage samples [22, 26, 50].

Regeneration culture

Isolated chondrocytes from healthy, defect and OA cartilage were expanded in a monolayer at 37°C and 5% CO2 at a seeding density of 5,000 cells per cm2 in expansion medium consisting of DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Thermo Scientific, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL/100 μg/mL) and 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). After two passages (P2), the chondrocytes were seeded on collagen type II-coated (chicken sternal cartilage; Sigma-Aldrich, #C9301) Millicell filters (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA), at 1.6 × 106 cells per cm2. Chondrocytes were redifferentiated for 28 days in redifferentiation medium consisting of DMEM, 0.2 mM l-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (AsAp; Sigma-Aldrich), 2% human serum albumin (Sanquin Blood Supply Foundation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL/100 μg/mL), 2% insuline-transferrine-selenium (ITS)-X (Invitrogen) and 5 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2; R&D Systems). Since fibrillar type II collagen was previously shown to induce IL-6 release from chondrocytes [32, 33], we also measured the release of IL-6 from P2 chondrocytes (n = 3 healthy donors) seeded at a density of 1.6 × 106 cells per cm2 on filters coated with type I collagen (rat tail; BD Biosciences, #354249), and denatured type I and II collagen. Collagen was denatured by heating for 45 minutes at 70°C. Levels of IL-6 in the conditioned media were determined by specific ELISA for IL-6 (Cyto-set®; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Endogenous IL-6 production of defect chondrocytes proved to be not significantly different from healthy chondrocytes, which were both much lower than that of OA chondrocytes. Therefore, the role of IL-6 endogenously produced by defect chondrocytes (n = 3) and OA chondrocytes (n = 3) was studied through blockage of IL-6 with an activity-inhibiting antibody. To this end, the medium was supplemented with either 1 or 4 ug/mL anti-hIL-6 (purified mouse monoclonal IgG1; R&D Systems, #MAB206) or IgG1 isotype control (R&D Systems, #MAB002). The dose of anti-hIL-6 was chosen based on an IL-6-dependent murine plasmacytoma proliferation assay, as described earlier [52]. Furthermore, IL-6 activity was blocked with 100 ng/mL tocilizumab (RoActemra®, Roche, Woerden, The Netherlands), a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 receptor. The concentration of tocilizumab was chosen based on previously observed average concentrations of IL-6 receptor in the synovial fluid of patients with OA of approximately 10 to 40 ng/mL [15, 16]. Since the effects of IL-6 inhibition were limited in expanded cells, we also verified the effects of IL-6 inhibition in freshly isolated OA cells (P0; n = 3).

Endogenous IL-6 production was relatively low in healthy chondrocytes, so the possible effects of high concentrations of IL-6 were further investigated by the addition of 10 ng/mL rhIL-6 with 25 ng/mL rhIL-6Rα (R&D Systems, #206-IL, #227-SR) to both healthy (n = 3) and OA (n = 3) chondrocytes. Medium was changed three times a week and supernatants were collected and stored at -80°C until later analysis. Per condition, six filters were seeded with chondrocytes, five for biochemical analyses and one for histological evaluation.

Osteoarthritic cartilage explant culture

OA cartilage from three donors was cut into explants of approximately 1 mm by 1 mm with a mean wet weight (± SD) of 7.8 ± 2.8 mg. Cartilage explants were cultured for 14 days in explant medium consisting of DMEM, penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL/100 μg/mL), 1% ITS-X, 0.1 mM AsAp and 0.2% proline (Sigma-Aldrich), which was supplemented with either 0 or 25% (v/v) pooled OA synovial fluid from eight donors. Six explants per condition were used, five for biochemical analyses and one for histological evaluation. To study the role of IL-6 present in the synovial fluid, 4 ug/mL anti-hIL-6 or IgG1 isotype control and/or 100 ng/mL tocilizumab were added to the medium. Medium was changed three times per week and collected and stored at -20°C until later analysis.

The role of IL-6 was also studied by the addition of IL-6 to the culture medium. Explants from eight OA donors (11.3 ± 3.8 mg, minimum of three explants per condition) were pre-cultured for 24 hours in culture medium after which rhIL-6 (50 ng/mL) with IL-6 receptor (rhIL-6Rα; 200 ng/mL) [53] was added to experimental groups, but not to control groups. Explants were cultured for an additional 10 days with medium renewal every other day and the conditioned medium was collected and stored at -20°C until later analysis.

Glycosaminoglycan and DNA analysis

After culture, the explants and the regenerated tissue were digested overnight in a papain buffer (250 μg/mL papain (Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mM EDTA and 5 mM L-cysteine) at 56°C, followed by quantification of the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) content using the dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay [54]. The ratio of absorption at 540 nm to 595 nm was used to calculate the GAG content, using chondroitin-6-sulphate (shark; Sigma-Aldrich) as a standard. The GAG content in conditioned medium was also measured.

The DNA content in the papain digests was determined using a Picogreen DNA assay (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Histological evaluation

Both regenerated tissue and explants were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in alcohol, rinsed in xylene and infiltrated and embedded with paraffin. For histology, 5 μm sections were stained with safranin-O (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for GAG and counterstained with Weigert's haematoxylin (Klinipath, Duiven, The Netherlands) and 0.4% fast green (Merck) for nuclei and cytoplasm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between controls and IL-6 blocked samples and differences between controls and IL-6 supplemented samples were determined by univariate analysis of variance using a randomized block design and post hoc LSD-test when four or more conditions were compared to each other. Differences in IL-6 concentration were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test, using post hoc Mann-Whitney U-test and Bonferroni correction for synovial fluids, and using nested ANOVA with post hoc t-test and Bonferroni correction for conditioned media. Differences between the various collagen coatings were determined by univariate analysis of variance with post hoc t-test with Bonferroni correction.

Results

IL-6 in synovial fluid

The synovial fluid of donors with symptomatic cartilage lesions contained significantly more IL-6 than that of healthy donors (261 ± 385 pg/mL versus 64 ± 120 pg/mL, P = 0.001), and was slightly lower but not significantly different from OA patients (396 ± 508 pg/mL, Figure 1). IL-6 levels in the five patients with symptomatic focal cartilage defects and associated or previous ACL injury and/or partial menisectomy were not significantly different from the group as a whole (154 ± 70 pg/mL, P = 0.6).

IL6 production in cell culture

In regeneration cultures, chondrocytes of the various origins produced IL-6 reaching concentrations that were at least 10-fold higher than the concentrations present in the synovial fluid of the corresponding donor category (Figure 2). OA chondrocytes (9,368 ± 3,284 pg/mL) produced significantly more IL-6 than both healthy (2,814 ± 995 pg/mL) and defect chondrocytes (3,246 ± 2,089 pg/mL, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in IL-6 production between healthy and defect chondrocytes.

Cartilage regeneration culture: IL-6 production. Passage 2 expanded chondrocytes from healthy (H), defect (CD) and osteoarthritic (OA) cartilage were seeded at high density on type II collagen-coated filters and cultured during 28 days. Concentrations of IL-6 in conditioned media of chondrocytes during regeneration on Day 7 is shown; a = P < 0.001.

To verify whether IL-6 production during regeneration was induced by the fibrillar type II collagen used for coating the filters in this model, we measured IL-6 production of regenerating chondrocytes on filters coated with various collagens. There was no difference in IL-6 production between type I and II collagen-coated filters and also not between native or denatured collagen-coated filters (Table 1). GAG and DNA content were also similar between the various coatings.

Regeneration culture

To evaluate whether the high levels of IL-6 produced by the chondrocytes during regeneration play a direct role in cartilage regeneration, IL-6 was inhibited using an activity-inhibiting antibody during regeneration of P2-expanded defect- and OA chondrocytes. As no difference was found in IL-6 production between healthy and defect chondrocytes, only defect and osteoarthritic chondrocytes were studied. No effects were found on cartilage matrix production, although an increase in DNA content was found in OA chondrocytes (P = 0.009, Figure 3). Verification of these results using non-expanded osteoarthritic chondrocytes similarly showed no effect on cartilage matrix production and also the effect on DNA was no longer found (data not shown). Antagonism of the IL-6 receptor with tocilizumab in osteoarthritic chondrocytes failed to influence GAG and DNA content (data not shown).

Cartilage regeneration after inhibition of endogenously produced IL-6. Cartilage regeneration cultures of three defect (CD) and three osteoarthritic (OA) donors with blockage of endogenous IL-6 with an activity-inhibiting antibody. (a-c) GAG content, GAG release and DNA content after 28 days of culture in IL-6 blocked samples depicted as percent of control samples (mean ± SD); a = P = 0.009. (d) Safranin-O staining of representative CD and OA chondrocyte donors regenerating either without (control; IgG isotype) or with inhibition (anti-IL-6) of endogenous IL-6. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

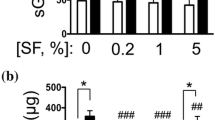

In healthy and defect chondrocytes endogenous IL-6 production was much lower than in OA chondrocytes. We, therefore, hypothesized that these cells could be more responsive to stimulation with exogenous IL-6 than OA chondrocytes. To examine whether exogenously added IL-6 could affect regeneration, 10 ng/mL rhIL-6 with 25 ng/mL rhIL-6Rα was added during regeneration culture of healthy and OA chondrocytes. In healthy chondrocytes, exogenous IL-6 increased GAG production in the neocartilage and a higher GAG/DNA ratio was found (P = 0.002, Figure 4A, D). In OA chondrocytes, IL-6 decreased GAG release (P < 0.001, Figure 4B) without affecting final GAG content in the neocartilage. DNA content was not modified by the addition of IL-6 (Figure 4C).

Cartilage regeneration with addition of IL-6. Cartilage regeneration cultures of three healthy (H) and three osteoarthritic (OA) donors with addition of rhIL-6 (10 ng/mL) and rhIL-6Rα (25 ng/mL). (a-c) GAG content, GAG release and DNA content of IL-6 supplemented samples depicted as percentage of control samples (mean ± SD); a = P = 0.009, b = P < 0.001. (d) Safranin-O staining of neocartilage generated by chondrocytes from healthy and osteoarthritic donors without or with addition of rhIL-6. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

Osteoarthritic explant culture

To study the effect of high levels of IL-6 present in the synovial fluid on resident cartilage in the knee, we performed OA cartilage explant studies in the presence of OA synovial fluid in which IL-6 was inhibited. Ideally, we would have also liked to perform these experiments using synovial fluid and cartilage explants from patients with chondral defects, but due to the very limited amount of material that can be obtained from these patients this was not feasible. In the absence of synovial fluid, inhibition of IL-6 did not alter the GAG and DNA content of the cartilage explants, nor was GAG release affected (data not shown). However, when IL-6 was inhibited in the presence of synovial fluid a trend towards a decreased GAG content of the explants was observed (P = 0.06, Figure 5A). In the absence of IL-6 inhibitors, the addition of synovial fluid increased the DNA content of explants (54.0 ± 28.0 μg/g cartilage versus 33.6 ± 20.9 μg/gr cartilage, P = 0.002), and this effect was abolished by blocking IL-6 (42 ± 20 versus 54 ± 28 μg/g cartilage). GAG release was neither affected by the addition of synovial fluid nor by inhibition of IL-6 (Figure 5C).

OA cartilage explant culture with inhibition of synovial fluid IL-6 or addition of exogenous IL-6. (a, c) GAG content and GAG release in OA cartilage explants from three donors cultured either in medium only, medium supplemented with 25% OA synovial fluid (SF) or medium with 25% OA synovial fluid in which IL-6 is blocked with an activity-inhibiting antibody (mean ± SD in mg/g); P = 0.06. (b, d) GAG content and GAG release in OA cartilage explants from eight donors cultured in the presence or absence of rhIL-6 (50 ng/mL) with rhIL-6Rα (200 ng/mL).

Exogenous IL-6 in combination with soluble IL-6 receptor in the absence of synovial fluid did not alter the GAG (Figure 5B) or DNA content of the explants and also did not modulate GAG release (Figure 5D).

Discussion

In this study, we show increased IL-6 levels in the synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic cartilage defects compared to normal subjects. The IL-6 levels in patients with symptomatic cartilage defects were comparable to levels in patients with OA. Furthermore, we demonstrated for the first time that chondrocytes, especially OA chondrocytes, produce high concentrations of IL-6 during regeneration. Inhibition of this endogenously produced IL-6 did not affect cartilage matrix turnover, but addition of extra IL-6 increased the GAG content of neocartilage formed by healthy chondrocytes and decreased GAG release by osteoarthritic chondrocytes in an in vitro regeneration model. Furthermore, inhibition of IL-6 present in the synovial fluid showed a trend towards decreased matrix production in OA explants. Collectively, these results point towards an anabolic role of IL-6 in cartilage repair, albeit with limited effects.

Inflammatory mediators secreted by synovium and present in the synovial fluid have been demonstrated to affect cartilage regeneration in vitro [23–26, 55]. Therefore, it is essential to characterize the mediators present in the synovial fluid of symptomatic cartilage defects and osteoarthritic joints and to determine their role in cartilage metabolism, in order to verify whether the outcomes of cartilage repair procedures, such as ACI, could potentially be enhanced by modulating the intra-articular environment. Levels of IL-6 comparable to those reported here were previously shown in the synovial fluid from healthy [10] and OA [10, 12, 56] joints; however, only limited data were available on IL-6 levels in joints with symptomatic focal cartilage defects. These are typically the joints that will be treated to stimulate regeneration of cartilage with techniques, such as ACI, and, therefore, of particular importance for regenerative medicine strategies. Only one study has reported on the levels of IL-6 in cartilage lesions of variable depth, but did not specify whether the damage was focal or whether more generalized OA-like cartilage degeneration was present in the knee [56], which is an important selection criterion for the indication of ACI. However, IL-6 levels seemed to correlate with the grade of cartilage damage as the synovial fluid concentration of IL-6 increased with lesion severity. In our study, only symptomatic focal grade III and IV cartilage lesions in otherwise healthy knees were included. This is more clinically relevant for cartilage regeneration, although no distinction was made between grade III and grade IV defects.

Most likely, IL-6 present in the synovial fluid originates from the cells in the synovial membrane [15]. In addition, adipose tissue, including that of the fat pad in the knee, is an important source of inflammatory mediators, including IL-6 [57, 58], at least partly explaining the association of OA with obesity. Although we did not collect information regarding the body mass index (BMI) of the donors, it is possible that the OA donors were more obese, which could account at least partly for the higher levels of IL-6 found in OA synovial fluid. Furthermore, chondrocytes can produce IL-6, although chondrocytes embedded in their original matrix produce very little IL-6 [26]. However, during regeneration, chondrocytes produced high levels of IL-6, which, if they were then implanted intra-articularly, in theory, could cause high local concentrations and affect cartilage regeneration. The production of IL-6 was not a result of the type II collagen used in this model, as filters coated with type I collagen, which is not capable of inducing IL-6 [32], resulted in the same IL-6 production. Possibly, IL-6 production was induced by the TGF-β included in the current in vitro regeneration model, as was reported previously [29]. However, those data were obtained using non-expanded chondrocytes in the short term, rather than during regeneration culture. In addition, the differences in IL-6 production between various cell types cannot be explained by the addition of TGF-β, as this was the same for all cell types.

Little is known about the role of IL-6 during regeneration, but inhibition of IL-6 did not influence GAG or DNA content of the newly formed cartilage. Possibly the effect of IL-6 inhibition on cartilage formation was partly masked by the regenerative effect of TGF-β. However, addition of IL-6 did decrease GAG release by OA chondrocytes. In addition, in explant culture, no TGF-β was present and no clear effect was found here.

The results found here are partly in contrast to the previously described reduction of cartilage matrix gene expression and inhibition of proteoglycan synthesis [37–39, 59]. Although the latter two effects of IL-6 can be seen as inhibitory, inhibition of synthesis can still be accompanied by a lack of net change in proteoglycan content if its deposition is increased. Indeed, we observed less GAG release into the medium without affecting final GAG content upon the addition of IL-6 to OA chondrocytes, suggesting that although total synthesis is reduced, final regeneration is the same. Unfortunately this aspect of cartilage regeneration is usually not addressed. Other differences between the current and previous studies evaluating the effect of IL-6 on chondrocyte metabolism may be based on the cells used, which were mainly bovine, porcine or rabbit chondrocytes. When human OA chondrocytes were used, actually no effect of IL-6 was seen on aggrecan production [44]. In the current study, addition of IL-6 to healthy chondrocytes, which produce much less IL-6, resulted in increased GAGs being deposited into the newly formed matrix. This is in line with previous studies using healthy human chondrocytes, revealing anabolic mechanisms upon addition of IL-6, such as up-regulation of TIMP-1 and bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) [36, 60]. Furthermore, in osteoarthritic explant culture, a trend towards decreased matrix production upon inhibition of IL-6 was observed. Exogenous IL-6 in combination with soluble IL-6 receptor in the absence of synovial fluid did not alter cartilage turnover, suggesting that IL-6 in the synovial fluid exerts its effects via interaction with other factors. The limited availability of synovial fluid restricted its presence in culture to 25% and, therefore, higher percentages may have yielded more pronounced effects. The limited effect of IL-6 inhibition on cartilage matrix turnover is unlikely to be due to a lack of inhibitory activity of the antibody, as this and other similar antibodies have demonstrated effectiveness in inhibiting IL-6 bioactivity in other models, including models with chondrocytes as target cells [39, 61]. Diffusion limitations in the cartilage explants may have prevented complete penetration of the antibodies to inhibit locally produced IL-6, thus still allowing for paracrine signalling. However, this is probably limited as chondrocytes in their native extracellular matrix hardly produce IL-6 [26]. Penetration of tocilizumab, required for the inhibition of IL-6 signalling, into the newly formed cartilage during regeneration may have been suboptimal, allowing IL-6 signalling through the membrane-bound IL-6 receptor. This could explain the lack of effect that tocilizumab had during osteoarthritic chondrocyte regeneration.

The role of IL-6 in cartilage metabolism has been the subject of much debate. IL-6 is often described as a modulatory factor, because it can induce both anabolic and catabolic mechanisms. Recently, IL-6 injection into the knee joint of mice was described to cause cartilage destruction, but in that study, like in many others, supra physiological concentrations of IL-6 were used [43]. Concentrations of IL-6 similar to those found in the synovial fluid usually do not have effects on the expression of cartilage matrix proteins in cartilage [44–46]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an effect of physiological concentrations of IL-6 on cartilage matrix production during regeneration, albeit modestly. IL-6 is known to be induced by various catabolic stimuli present in OA, such as IL-1β [30], prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [31], increased shear stress [62] and extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronan fragments [63] and matrillin-3 [32]. IL-6, in turn, is capable of inducing factors, such as metalloproteinases (MMPs) [64], TGFβ [65], vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [66] and many others which are important for tissue remodelling. In bone IL-6 also induces remodelling through increased osteoclastogenesis [67], which is thought to be important in the observed inhibition of radiographic disease progression in RA patients treated with tocilizumab [6, 68]. IL-6 has also been shown to have anabolic effects on cartilage, both indirectly through the up-regulation of factors, such as TIMP-1 [60], BMP-7 [36] and TGFβ [65], as well as directly through the up-regulation of cartilage matrix proteins [36]. In another study, injection of IL-6 into the joint cavity of mice stimulated proteoglycan synthesis in cartilage [69], while IL-6 knockout mice showed more extensive naturally occurring cartilage loss [42] and reduced proteoglycan synthesis [42, 70]. The current study indicates that IL-6 has a mainly anabolic role in in vitro cartilage regeneration, although the effects are not strong, with increased GAG production in healthy chondrocytes and decreased GAG release in OA chondrocytes. Possibly the IL-6 in the synovial fluid of patients with symptomatic cartilage defects is induced in the course of regeneration and plays a role in tissue regeneration after cartilage damage.

Although cartilage pathology seemed to clearly affect IL-6 production and at least part of the response to interference with this factor, several other donor-related factors may have additionally influenced the results. To start with, there is the typical age difference found between OA donors (average 70 years [71]) and patients with cartilage defects, which usually present around 30 years of age [72]. However, IL-6 levels were not found to correlate with age [73]. The use of post-mortem collection of healthy synovial fluid and cells as opposed to the intra-operative collection of OA and cartilage defect synovial fluid and cells is less likely to have affected the results. Previous work from our group showed that there was no difference in viability between freshly isolated chondrocytes from healthy (post-mortem obtained) and grade III cartilage defect tissue [49], which is in line with the observation that viability and cartilage matrix content is very much unaltered within the first 24 hours [74–76]. Synovial fluid is contained in a relatively isolated compartment [77, 78] and when kept at 4°C, levels of IL-6 have been shown to be stable for more than six hours [79].

Conclusions

This study indicates that the level of IL-6 is increased in joints with symptomatic cartilage defects or OA compared to healthy joints. Moreover, the elevated levels of IL-6 appear to promote anabolic metabolism of the resident chondrocytes, and seem beneficial for formation of neocartilage during in vitro regeneration. Further research is necessary to evaluate whether targeting multiple cytokines or pathways, including IL-6, may be an effective means to improve cartilage matrix production during ACI or microfracturing in symptomatic cartilage defects or OA.

Abbreviations

- ACI:

-

autologous chondrocyte implantation

- ACL:

-

anterior cruciate ligament

- bFGF:

-

basic fibroblast growth factor

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BMP-7:

-

bone morphogenetic protein-7

- DDR2:

-

discoidin domain receptor 2

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- DMMB:

-

dimethylmethylene blue

- GAG:

-

glycosaminoglycan

- HIF-2α:

-

hypoxia-inducible factor-2α

- IL-1:

-

interleukin-1

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- IL-6Rα:

-

interleukin-6 receptor α

- MMP:

-

metalloproteinase

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- PBS:

-

phosphate buffered saline

- PGE2:

-

prostaglandin E2

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- TIMP-1:

-

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1

- TGFβ:

-

transforming growth factor β

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VEGF:

-

vascular growth factor

References

Goldring MB, Otero M: Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011, 23: 471-478. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1.

McInnes IB, Schett G: The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365: 2205-2219. 10.1056/NEJMra1004965.

Liang B, Song Z, Wu B, Gardner D, Shealy D, Song XY, Wooley PH: Evaluation of anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody therapy using murine type II collagen-induced arthritis. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009, 6: 10-10.1186/1476-9255-6-10.

Jazayeri JA, Carroll GJ, Vernallis AB: Interleukin-6 subfamily cytokines and rheumatoid arthritis: role of antagonists. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10: 1-8. 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.09.019.

Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, Moreland LW, O'Dell J, Winthrop KL, Beukelman T, Bridges SL, Chatham WW, Paulus HE, Suarez-Almazor M, Bombardier C, Dougados M, Khanna D, King CM, Leong AL, Matteson EL, Schousboe JT, Moynihan E, Kolba KS, Jain A, Volkmann ER, Agrawal H, Bae S, Mudano AS, Patkar NM, Saag KG: 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012, 64: 625-639. 10.1002/acr.21641.

Kremer JM, Blanco R, Brzosko M, Burgos-Vargas R, Halland AM, Vernon E, Ambs P, Fleischmann R: Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to methotrexate: results from the double-blind treatment phase of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab safety and prevention of structural joint damage at one year. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63: 609-621. 10.1002/art.30158.

Hashimoto J, Garnero P, van der Heijde D, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Yoshikawa H, Nishimoto N: Humanized anti-interleukin-6-receptor antibody (tocilizumab) monotherapy is more effective in slowing radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis at high baseline risk for structural damage evaluated with levels of biomarkers, radiography, and BMI: data from the SAMURAI study. Mod Rheumatol. 2011, 21: 10-15. 10.1007/s10165-010-0325-3.

Garnero P, Thompson E, Woodworth T, Smolen JS: Rapid and sustained improvement in bone and cartilage turnover markers with the anti-interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab plus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate: results from a substudy of the multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab in inadequate responders to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 33-43. 10.1002/art.25053.

Gobezie R, Kho A, Krastins B, Sarracino DA, Thornhill TS, Chase M, Millett PJ, Lee DM: High abundance synovial fluid proteome: distinct profiles in health and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9: R36-10.1186/ar2172.

Kokebie R, Aggarwal R, Lidder S, Hakimiyan AA, Rueger DC, Block JA, Chubinskaya S: The role of synovial fluid markers of catabolism and anabolism in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and asymptomatic organ donors. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011, 13: R50-10.1186/ar3293.

Scanzello CR, Umoh E, Pessler F, Diaz-Torne C, Miles T, Dicarlo E, Potter HG, Mandl L, Marx R, Rodeo S, Goldring SR, Crow MK: Local cytokine profiles in knee osteoarthritis: elevated synovial fluid interleukin-15 differentiates early from end-stage disease. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009, 17: 1040-1048. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.02.011.

Regan EA, Bowler RP, Crapo JD: Joint fluid antioxidants are decreased in osteoarthritic joints compared to joints with macroscopically intact cartilage and subacute injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16: 515-521. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.09.001.

Doss F, Menard J, Hauschild M, Kreutzer HJ, Mittlmeier T, Muller-Steinhardt M, Muller B: Elevated IL-6 levels in the synovial fluid of osteoarthritis patients stem from plasma cells. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007, 36: 136-139. 10.1080/03009740701250785.

Ushiyama T, Chano T, Inoue K, Matsusue Y: Cytokine production in the infrapatellar fat pad: another source of cytokines in knee synovial fluids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003, 62: 108-112. 10.1136/ard.62.2.108.

Desgeorges A, Gabay C, Silacci P, Novick D, Roux-Lombard P, Grau G, Dayer JM, Vischer T, Guerne PA: Concentrations and origins of soluble interleukin 6 receptor-alpha in serum and synovial fluid. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 1510-1516.

Kotake S, Sato K, Kim KJ, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Nakamura I, Yamaguchi A, Kishimoto T, Suda T, Kashiwazaki S: Interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-6 receptors in the synovial fluids from rheumatoid arthritis patients are responsible for osteoclast-like cell formation. J Bone Miner Res. 1996, 11: 88-95.

Stannus O, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Parameswaran V, Quinn S, Burgess J, Ding C: Circulating levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha are associated with knee radiographic osteoarthritis and knee cartilage loss in older adults. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010, 18: 1441-1447. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.016.

Livshits G, Zhai G, Hart DJ, Kato BS, Wang H, Williams FM, Spector TD: Interleukin-6 is a significant predictor of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: the Chingford Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 2037-2045. 10.1002/art.24598.

Cuellar VG, Cuellar JM, Golish SR, Yeomans DC, Scuderi GJ: Cytokine profiling in acute anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy. 2010, 26: 1296-1301. 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.02.011.

Elsaid KA, Fleming BC, Oksendahl HL, Machan JT, Fadale PD, Hulstyn MJ, Shalvoy R, Jay GD: Decreased lubricin concentrations and markers of joint inflammation in the synovial fluid of patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 1707-1715. 10.1002/art.23495.

Catterall JB, Stabler TV, Flannery CR, Kraus VB: Changes in serum and synovial fluid biomarkers after acute injury (NCT00332254). Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12: R229-10.1186/ar3216.

Cuellar JM, Scuderi GJ, Cuellar VG, Golish SR, Yeomans DC: Diagnostic utility of cytokine biomarkers in the evaluation of acute knee pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009, 91: 2313-2320. 10.2106/JBJS.H.00835.

Vanlauwe J, Saris DB, Victor J, Almqvist KF, Bellemans J, Luyten FP, TIG/ACT/01/2000&EXT Study Group: Five-year outcome of characterized chondrocyte implantation versus microfracture for symptomatic cartilage defects of the knee: early treatment matters. Am J Sports Med. 2011, 39: 2566-2574. 10.1177/0363546511422220.

Yang KG, Saris DB, Verbout AJ, Creemers LB, Dhert WJ: The effect of synovial fluid from injured knee joints on in vitro chondrogenesis. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12: 2957-2964. 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2957.

Rodrigo JJ, Steadman JR, Syftestad G, Benton H, Silliman J: Effects of human knee synovial fluid on chondrogenesis in vitro. Am J Knee Surg. 1995, 8: 124-129.

Beekhuizen M, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Koevoet W, Saris DB, Dhert WJ, Creemers LB, van Osch GJ: Osteoarthritic synovial tissue inhibition of proteoglycan production in human osteoarthritic knee cartilage: establishment and characterization of a long-term cartilage-synovium coculture. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63: 1918-1927. 10.1002/art.30364.

Calamia V, Rocha B, Mateos J, Fernandez-Puente P, Ruiz-Romero C, Blanco FJ: Metabolic labeling of chondrocytes for the quantitative analysis of the interleukin-1-beta-mediated modulation of their intracellular and extracellular proteomes. J Proteome Res. 2011, 10: 3701-3711. 10.1021/pr200331k.

Henrotin YE, De Groote DD, Labasse AH, Gaspar SE, Zheng SX, Geenen VG, Reginster JY: Effects of exogenous IL-1 beta, TNF alpha, IL-6, IL-8 and LIF on cytokine production by human articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1996, 4: 163-173. 10.1016/S1063-4584(96)80012-4.

Guerne PA, Carson DA, Lotz M: IL-6 production by human articular chondrocytes. Modulation of its synthesis by cytokines, growth factors, and hormones in vitro. J Immunol. 1990, 144: 499-505.

Fan Z, Bau B, Yang H, Aigner T: IL-1beta induction of IL-6 and LIF in normal articular human chondrocytes involves the ERK, p38 and NFkappaB signaling pathways. Cytokine. 2004, 28: 17-24. 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.06.003.

Wang P, Zhu F, Konstantopoulos K: Prostaglandin E2 induces interleukin-6 expression in human chondrocytes via cAMP/protein kinase A- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010, 298: C1445-1456. 10.1152/ajpcell.00508.2009.

Klatt AR, Paul-Klausch B, Klinger G, Kuhn G, Renno JH, Banerjee M, Malchau G, Wielckens K: A critical role for collagen II in cartilage matrix degradation: collagen II induces pro-inflammatory cytokines and MMPs in primary human chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 2009, 27: 65-70. 10.1002/jor.20716.

Klatt AR, Zech D, Kuhn G, Paul-Klausch B, Klinger G, Renno JH, Schmidt J, Malchau G, Wielckens K: Discoidin domain receptor 2 mediates the collagen II-dependent release of interleukin-6 in primary human chondrocytes. J Pathol. 2009, 218: 241-247. 10.1002/path.2529.

Sims NA, Walsh NC: GP130 cytokines and bone remodelling in health and disease. BMB Rep. 2010, 43: 513-523. 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.8.513.

Schaible HG, von Banchet GS, Boettger MK, Brauer R, Gajda M, Richter F, Hensellek S, Brenn D, Natura G: The role of proinflammatory cytokines in the generation and maintenance of joint pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010, 1193: 60-69. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05301.x.

Namba A, Aida Y, Suzuki N, Watanabe Y, Kawato T, Motohashi M, Maeno M, Matsumura H, Matsumoto M: Effects of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor on the expression of cartilage matrix proteins in human chondrocytes. Connect Tissue Res. 2007, 48: 263-270. 10.1080/03008200701587513.

Legendre F, Dudhia J, Pujol JP, Bogdanowicz P: JAK/STAT but not ERK1/ERK2 pathway mediates interleukin (IL)-6/soluble IL-6R down-regulation of Type II collagen, aggrecan core, and link protein transcription in articular chondrocytes. Association with a down-regulation of SOX9 expression. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 2903-2912. 10.1074/jbc.M110773200.

Poree B, Kypriotou M, Chadjichristos C, Beauchef G, Renard E, Legendre F, Melin M, Gueret S, Hartmann DJ, Mallein-Gerin F, Pujol JP, Boumediene K, Galéra P: Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and/or soluble IL-6 receptor down-regulation of human type II collagen gene expression in articular chondrocytes requires a decrease of Sp1.Sp3 ratio and of the binding activity of both factors to the COL2A1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283: 4850-4865.

Guerne PA, Desgeorges A, Jaspar JM, Relic B, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P, Dayer JM: Effects of IL-6 and its soluble receptor on proteoglycan synthesis and NO release by human articular chondrocytes: comparison with IL-1. Modulation by dexamethasone. Matrix Biol. 1999, 18: 253-260. 10.1016/S0945-053X(99)00021-9.

Flannery CR, Little CB, Hughes CE, Curtis CL, Caterson B, Jones SA: IL-6 and its soluble receptor augment aggrecanase-mediated proteoglycan catabolism in articular cartilage. Matrix Biol. 2000, 19: 549-553. 10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00111-6.

Rogerson FM, Chung YM, Deutscher ME, Last K, Fosang AJ: Cytokine-induced increases in ADAMTS-4 messenger RNA expression do not lead to increased aggrecanase activity in ADAMTS-5-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 3365-3373. 10.1002/art.27661.

de Hooge AS, van de Loo FA, Bennink MB, Arntz OJ, de Hooge P, van den Berg WB: Male IL-6 gene knock out mice developed more advanced osteoarthritis upon aging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005, 13: 66-73. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.09.011.

Ryu JH, Yang S, Shin Y, Rhee J, Chun CH, Chun JS: Interleukin-6 plays an essential role in hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha-induced experimental osteoarthritic cartilage destruction in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63: 2732-2743. 10.1002/art.30451.

Sanchez C, Deberg MA, Burton S, Devel P, Reginster JY, Henrotin YE: Differential regulation of chondrocyte metabolism by oncostatin M and interleukin-6. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004, 12: 801-810. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.06.011.

Ley C, Svala E, Nilton A, Lindahl A, Eloranta ML, Ekman S, Ski Ldebrand E: Effects of high mobility group box protein-1, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 on cartilage matrix metabolism in three-dimensional equine chondrocyte cultures. Connect Tissue Res. 2011, 52: 290-300. 10.3109/03008207.2010.523803.

McNulty AL, Miller MR, O'Connor SK, Guilak F: The effects of adipokines on cartilage and meniscus catabolism. Connect Tissue Res. 2011, 52: 523-533. 10.3109/03008207.2011.597902.

[Dutch federation of Biomedical Scientific Societies]. [http://www.federa.org]

van Diest PJ: No consent should be needed for using leftover body material for scientific purposes. For. BMJ. 2002, 325: 648-651. 10.1136/bmj.325.7365.648.

Bekkers JE, Saris DB, Tsuchida AI, van Rijen M, Dhert WJ, Creemers LB: Chondrogenic potential of articular chondrocytes depends on their original location. [Submitted for publication.]

de Jager W, Prakken BJ, Bijlsma JW, Kuis W, Rijkers GT: Improved multiplex immunoassay performance in human plasma and synovial fluid following removal of interfering heterophilic antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 2005, 300: 124-135. 10.1016/j.jim.2005.03.009.

de Jager W, te Velthuis H, Prakken BJ, Kuis W, Rijkers GT: Simultaneous detection of 15 human cytokines in a single sample of stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003, 10: 133-139.

Nordan RP, Potter M: A macrophage-derived factor required by plasmacytomas for survival and proliferation in vitro. Science. 1986, 233: 566-569. 10.1126/science.3726549.

Rowan AD, Koshy PJ, Shingleton WD, Degnan BA, Heath JK, Vernallis AB, Spaull JR, Life PF, Hudson K, Cawston TE: Synergistic effects of glycoprotein 130 binding cytokines in combination with interleukin-1 on cartilage collagen breakdown. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 1620-1632. 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1620::AID-ART285>3.0.CO;2-B.

Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ: A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connect Tissue Res. 1982, 9: 247-248. 10.3109/03008208209160269.

Heldens GT, Davidson EN, Vitters EL, Schreurs BW, Piek E, Berg WB, Kraan PM: Catabolic factors and osteoarthritis-conditioned medium inhibit chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012, 18: 45-54.

Maiotti M, Monteleone G, Tarantino U, Fasciglione GF, Marini S, Coletta M: Correlation between osteoarthritic cartilage damage and levels of proteinases and proteinase inhibitors in synovial fluid from the knee joint. Arthroscopy. 2000, 16: 522-526. 10.1053/jars.2000.4632.

Klein-Wieringa IR, Kloppenburg M, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Yusuf E, Kwekkeboom JC, El-Bannoudi H, Nelissen RG, Zuurmond A, Stojanovic-Susulic V, Van Osch GJ, Toes RE, Joan-Facsinay A: The infrapatellar fat pad of patients with osteoarthritis has an inflammatory phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70: 851-857. 10.1136/ard.2010.140046.

Distel E, Cadoudal T, Durant S, Poignard A, Chevalier X, Benelli C: The infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis: an important source of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 3374-3377. 10.1002/art.24881.

Hui W, Bell M, Carroll G: Oncostatin M (OSM) stimulates resorption and inhibits synthesis of proteoglycan in porcine articular cartilage explants. Cytokine. 1996, 8: 495-500. 10.1006/cyto.1996.0067.

Silacci P, Dayer JM, Desgeorges A, Peter R, Manueddu C, Guerne PA: Interleukin (IL)-6 and its soluble receptor induce TIMP-1 expression in synoviocytes and chondrocytes, and block IL-1-induced collagenolytic activity. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273: 13625-13629. 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13625.

Long D, Blake S, Song XY, Lark M, Loeser RF: Human articular chondrocytes produce IL-7 and respond to IL-7 with increased production of matrix metalloproteinase-13. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008, 10: R23-10.1186/ar2376.

Wang P, Zhu F, Lee NH, Konstantopoulos K: Shear-induced interleukin-6 synthesis in chondrocytes: roles of E prostanoid (EP) 2 and EP3 in cAMP/protein kinase A- and PI3-K/Akt-dependent NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285: 24793-24804. 10.1074/jbc.M110.110320.

Pulai JI, Chen H, Im HJ, Kumar S, Hanning C, Hegde PS, Loeser RF: NF-kappa B mediates the stimulation of cytokine and chemokine expression by human articular chondrocytes in response to fibronectin fragments. J Immunol. 2005, 174: 5781-5788.

Hashizume M, Mihara M: Desirable effect of combination therapy with high molecular weight hyaluronate and NSAIDs on MMP production. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009, 17: 1513-1518. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.018.

Villiger PM, Kusari AB, ten Dijke P, Lotz M: IL-1 beta and IL-6 selectively induce transforming growth factor-beta isoforms in human articular chondrocytes. J Immunol. 1993, 151: 3337-3344.

Hashizume M, Hayakawa N, Suzuki M, Mihara M: IL-6/sIL-6R trans-signalling, but not TNF-alpha induced angiogenesis in a HUVEC and synovial cell co-culture system. Rheumatol Int. 2009, 29: 1449-1454. 10.1007/s00296-009-0885-8.

De Benedetti F: The impact of chronic inflammation on the growing skeleton: lessons from interleukin-6 transgenic mice. Horm Res. 2009, 72 (Suppl 1): 26-29.

Le Goff B, Blanchard F, Berthelot JM, Heymann D, Maugars Y: Role for interleukin-6 in structural joint damage and systemic bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010, 77: 201-205. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.03.002.

van de Loo FA, Joosten LA, van Lent PL, Arntz OJ, van den Berg WB: Role of interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-6 in cartilage proteoglycan metabolism and destruction. Effect of in situ blocking in murine antigen- and zymosan-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 164-172. 10.1002/art.1780380204.

van de Loo FA, Kuiper S, van Enckevort FH, Arntz OJ, van den Berg WB: Interleukin-6 reduces cartilage destruction during experimental arthritis. A study in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 1997, 151: 177-191.

Klop C, de Vries F, Lalmohamed A, Mastbergen SC, Leufkens HG, Noort-van der Laan WH, Bijlsma JW, Welsing PM: COX-2-selective NSAIDs and risk of hip or knee replacements: a population-based case-control study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012, 91: 387-394. 10.1007/s00223-012-9646-x.

Heir S, Nerhus TK, Rotterud JH, Loken S, Ekeland A, Engebretsen L, Aroen A: Focal cartilage defects in the knee impair quality of life as much as severe osteoarthritis: a comparison of knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score in 4 patient categories scheduled for knee surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010, 38: 231-237. 10.1177/0363546509352157.

Rubenhagen R, Schuttrumpf JP, Sturmer KM, Frosch KH: Interleukin-7 levels in synovial fluid increase with age and MMP-1 levels decrease with progression of osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2012, 83: 59-64. 10.3109/17453674.2011.645195.

Pallante AL, Bae WC, Chen AC, Gortz S, Bugbee WD, Sah RL: Chondrocyte viability is higher after prolonged storage at 37 degrees C than at 4 degrees C for osteochondral grafts. Am J Sports Med. 2009, 37 (Suppl 1): 24S-32S.

Lasczkowski GE, Aigner T, Gamerdinger U, Weiler G, Bratzke H: Visualization of postmortem chondrocyte damage by vital staining and confocal laser scanning 3D microscopy. J Forensic Sci. 2002, 47: 663-666.

Drobnic M, Mars T, Alibegovic A, Bole V, Balazic J, Grubic Z, Brecelj J: Viability of human chondrocytes in an ex vivo model in relation to temperature and cartilage depth. Folia Biol (Praha). 2005, 51: 103-108.

Madea B, Kreuser C, Banaschak S: Postmortem biochemical examination of synovial fluid--a preliminary study. Forensic Sci Int. 2001, 118: 29-35. 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00372-8.

Tumram NK, Bardale RV, Dongre AP: Postmortem analysis of synovial fluid and vitreous humour for determination of death interval: a comparative study. Forensic Sci Int. 2011, 204: 186-190. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.06.007.

Flower L, Ahuja RH, Humphries SE, Mohamed-Ali V: Effects of sample handling on the stability of interleukin 6, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and leptin. Cytokine. 2000, 12: 1712-1716. 10.1006/cyto.2000.0764.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank P. Westers, PhD, for his statistical advice, W. de Jager, PhD, for his assistance with the multiplex ELISA and Peter Levett, BSc, for his help with language editing. This research forms part of the Projects P2.01 IDiDAS and P2.02 of the research program of the Biomedical Materials Institute, co-funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation. L.B. Creemers is funded by the Dutch Arthritis Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AT, MB, MR, GvO, WD, DS and LC designed the study. JB and DS provided the study material. AT, MB, MR, JB, AB and BG acquired the data. AT, MB, MR, GvO, AB, BG, DS and LC analyzed and interpreted the data. AT and MB drafted the manuscript. MR, GvO, JB, AB, BG, WD, DS and LC critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Anika I Tsuchida, Michiel Beekhuizen contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuchida, A.I., Beekhuizen, M., Rutgers, M. et al. Interleukin-6 is elevated in synovial fluid of patients with focal cartilage defects and stimulates cartilage matrix production in an in vitro regeneration model. Arthritis Res Ther 14, R262 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4107

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4107