Abstract

The idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are chronic autoimmune disorders sharing the clinical symptom of muscle weakness and, in typical cases, inflammatory cell infiltrates in muscle tissue. During the last decade, novel information has accumulated supporting a role of both the innate and adaptive immune systems in myositis and suggesting that different molecular pathways predominate in different subsets of myositis. The type I interferon activity is one such novel pathway identified in some subsets of myositis. Furthermore, nonimmunological pathways have been identified, suggesting that factors other than direct T cell-mediated muscle fibre necrosis could have a role in the development of muscle weakness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, collectively called myositis, constitute a heterogeneous group of chronic disorders sharing the predominating clinical symptom of muscle weakness and, in classical cases, histopathological signs of inflammation in muscle tissue. Immunohistochemical analyses of human muscle biopsies have characterised two major types of cellular infiltrates defined by localisation and cellular phenotypes: (a) endomysial inflammatory infiltrates composed of mononuclear cells with an appreciable number of T cells, typically surrounding muscle fibres without features indicating degeneration or necrosis, and with a high prevalence of CD8+ T cells, but also CD4+ T cells, and the presence of macrophages, and (b) perivascular infiltrates composed of T cells (mainly of the CD4+ phenotype), macrophages, and to some extent B cells [1–3]. More recently, it was demonstrated that some of the CD4+cells in the perivascular infiltrates are plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs) [4]. The endomysial infiltrates suggested an immune reaction directed toward muscle fibres and were suggested to be typical for polymyositis and inclusion body myositis, whereas the perivascular infiltrates indicated an immune reaction against blood vessels and were typical for dermatomyositis. However, these histopathological features may sometimes overlap and, in some cases, the histopathological changes are scarce and unspecific and a histopathological distinction between polymyositis and dermatomyositis may not be as clear-cut as previously suggested. 'Rimmed vacuoles' and inclusions in muscle fibres, which constitute a third histopathological finding, are characteristic of inclusion body myositis, which is clinically different from polymyositis and dermatomyositis by slowly progressive weakness of proximal leg and distal arm muscles with pronounced atrophy and by a general resistance to immunosuppressive treatment. This information suggests that nonimmune mechanisms are important in inclusion body myositis; however, this will not be further discussed in this review.

The weak correlation between the amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate in muscle tissue and the degree of clinical overt muscle impairment has become the focus of scientific investigations over the past years. The questions of how and why muscle performance could be affected even without classical signs of muscle inflammation have developed several new hypotheses concerning nonimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of myositis. In addition, new data have become available suggesting that myositis specific autoantibodies (MSAs) are clinically useful as a diagnostic tool and for identifying distinct clinical subsets of myositis with distinct molecular pathways. In this review, we will discuss both immunological and nonimmunological perspectives of how and why polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients develop muscle weakness and, supported by recent novel data, how autoantibody profiles could be used for a new subclassification of myositis and for identifying novel molecular pathways that could be relevant for future therapies.

Immune cells in muscle tissue of myositis patients

The molecular basis of myositis is heterogeneous and involves several complexes of cellular compartments. We have only just started to understand the orchestrated life of T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) in myositis and still many questions about how this usually effective system can go awry and result in false immune-mediated reactions remain unanswered.

To date, no relevant animal model for studying the role of immune cells in myositis exists. Thus, a possible way to investigate the molecular pathways in inflammatory myopathies is to analyse the molecular expression patterns in the target organ, the skeletal muscle (for example, from patients in different phases of disease), and to correlate these molecular findings with clinical outcome measures (for example, muscle strength tests). We have prospectively investigated myositis patients in an early phase of their disease, in an established disease phase before and after immunosuppressive therapies, as well as in a late chronic phase of disease. Such information has provided a novel understanding of molecular pathways of myositis (Figure 1).

A schematic figure of muscle tissue from myositis patients with or without inflammatory infiltrates. (1) Early in the disease, before any signs of mononuclear cell infiltrates in the muscle tissue, patients have been found to express autoantibodies (even before the development of myositis), capillaries often having the appearance of high endothelial venules (HEVs) and an expression of adhesion molecules, interleukin-1-alpha (IL-1α) and/or chemokines, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I on muscle fibres, and a decreased number of capillaries together with an increased expression of vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF) on muscle fibres and in sera, suggestive of tissue hypoxia. Additionally, an increased number of fibres expressing high-mobility box chromosomal protein 1 (HMGB1) has been demonstrated early in the disease, and HMGB1 can induce MHC class I on muscle fibres. (2) All of these findings can also be found when inflammatory cell infiltrates are present. However, in these tissues, an increased production of a range of proinflammatory cytokines from mononuclear cells is also found. Moreover, non-necrotic fibres can be surrounded and sometimes invaded by cytotoxic T cells. These different pathogenic expressions from both immune and nonimmune reactions may all lead to muscle impairment. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IFN-α, interferon-alpha; PDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule. Partly adapted from Servier Medical Art.

T-cell expression

T cells are frequently present in the muscle tissue in all subsets of myositis but with large individual variations. The effector function of the infiltrating T cells in muscle tissue has not yet been clarified. Electron microscopy studies of inflamed muscle tissue from polymyositis patients suggested that CD8+ T cells are cytotoxic to muscle fibres [5]. These CD8+ as well as CD4+ muscle-infiltrating T cells have been shown to be perforin-positive [6], suggesting a possible T cell-muscle cell interaction. Also, clonal expansions of T cells by muscle-infiltrating T cells have been found, which could suggest an antigen-driven process [7]. A cytotoxic effect of T cells is still a subject of controversy since no muscle-specific antigens have been identified and since an expression of the costimulatory molecules CD80/86, normally required for functional interaction, has not been detected in inflamed muscle fibres. However, this aspect does not exclude a T cell-mediated cytotoxic effect on muscle fibres since not all T cells require CD80/86 costimulation from a target cell to engage in cytotoxicity; this is mainly relevant for naïve T cells [8].

After conventional immunosuppressive treatment, inflammatory cell infiltrates in muscle tissue often decrease [9]. However, in some patients, the inflammatory cells may persist, particularly the T cells, and may be present even after high doses of glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive therapies [9–11]. In this context, the CD28null T cells, a phenotype of T cells also found in other autoimmune diseases, are of interest [12]. These T cells are apoptosis-resistant and are easily triggered to produce proinflammatory cytokines like interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α. In our group, we have found that polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients have a high frequency of CD4+and CD8+ CD28null T cells in the circulation and in muscle tissue [13]. However, the exact role of CD28null T cells in the disease mechanisms in myositis still needs to be determined.

Muscle biopsies from myositis patients are very heterogeneous and there is substantial variation in the number of T cells that can be detected in muscle biopsies. In biopsies with a large number of T cells, still only a limited number of T cell derived cytokines, such as IFN-γ, interleukin (IL)-2, and IL-4, could be detected and only a minority of T cells expressed these cytokines in muscle tissue of dermatomyositis and polymyositis patients [14–17]. However, several T cell-derived cytokines have been reported at the transcription level but the biological relevance of these in the absence of corresponding protein expression is less certain [3, 15, 18, 19]. Recently, a T-cell subtype, Th17, a producer of IL-17, has been observed in the muscle tissue of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Double-staining showed that both IL-17- and IFN-γ-producing cells expressed CD4 [20]. Whether these cells are sensitive to immunosuppressive treatment and how their expression correlates with clinical outcome measures are not yet known. So far, in cultured myoblasts, IL-17 has been shown to induce major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression as well as IL-6 and cell signalling factors such as nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-κB), C-Fos, and C-jun [21]. However, since myoblasts are mononuclear undifferentiated muscle cells, their behaviour may likely be quite different from that of differentiated muscle fibres. Taken together, the data on the function of T cells in myositis are insufficient and this needs further investigations.

Dendritic cell expression and the type I interferon system

Recently, DCs were reported in muscle tissue of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients [20, 22, 23]. DCs function as professional antigen-presenting cells and are central in the development of innate and adaptive immune responses. Both immature (CD1a) and mature (CD83+ and DC-LAMP) DCs as well as their ligands have been detected in the muscle tissue of myositis patients. The location differed between these cell populations, with a predominance of the immature DCs in the lymphocytic infiltrates and the mature DCs in perivascular and endomysial areas [20]. Similar numbers of CD83+ cells, levels of positive DC-LAMP cell counts, and DC-LAMP/CD83+ ratios were found in polymyositis and dermatomyositis [20]. The T cell-derived cytokines IL-17 and IFN-γ may have a role in the homing of DCs through the up-regulation of chemokine expression like CCL20, which attracts immature DCs and has been found in the muscle tissue of both polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients [20].

Also, PDCs, the major producers of type I IFN-α, have been identified in the muscle tissue of adults with polymyositis, dermatomyositis, or inclusion body myositis as well as in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis [22, 24, 25]. PDCs had a scattered distribution and endomysial and/or perivascular localisation but were also detected as scattered cells within large cellular infiltrates. Moreover, PDCs were significantly increased in patients with autoantibodies against anti-Jo-1 (antihistidyl-tRNA synthetase antibody) or anti-SSA/SSB compared with healthy individuals [24]. In many cases, PDCs were localised adjacent to MHC class I-positive fibres. The expression of BDCA-2-positive PDCs and the IFN-α/β-inducible MxA protein correlated with the MHC class I expression on muscle fibres. PDCs were also found in skin biopsies of dermatomyositis patients [26]. Although the role of PDCs has not been clarified, an increased expression of type I IFN-α/β-inducible genes or proteins both in muscle tissue and in peripheral blood has been reported for polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients [24, 25, 27, 28]. Furthermore, the type I IFN-inducible gene expression and the expression of IFN-regulated proteins in sera correlated with disease activity [27, 28]. An increased type I IFN activity, associated with clinical disease activity, in refractory myositis patients treated with TNF blockade was also described [29]. This is similar to what has been observed in patients with Sjögren syndrome treated with anti-TNF therapy [30]. Together, these observations support the notion that the type I IFN system plays an important role in the pathogenesis in subsets of patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis, which makes IFN-α a potential specific target for therapy in these patients.

Cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins

Proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins and some anti-inflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-beta have been found in myositis muscle tissue. Major cellular sources of these molecules are cells of the innate immune system. Other cellular sources are endothelial cells and muscle fibres. On a molecular level in muscle tissue, both differences and similarities have been reported in pro-inflammatory cytokine transcript profiles and protein expression pattern between inclusion body myositis and polymyositis patients, on one hand, and dermatomyositis patients on the other hand. The shared molecular data might indicate that the effector phase of the immune reaction in the different subsets of myositis is shared although the initiating trigger and inflammatory cell phenotype may differ. Moreover, these molecular data emphasise the importance of molecular studies for learning more about molecular disease mechanisms in different subsets of disease.

Some cytokines have been consistently recorded in muscle tissue from myositis patients with different clinical subsets and in different phases of disease but with clinically impaired muscle performance. This might indicate that they have a role in causing muscle weakness. These cytokines, IL-1α and IL-1β [9, 31, 32], are expressed even after immunosuppressive treatment, IL-1α mainly in endothelial cells and IL-1β in scattered inflammatory cells [32]. Not only the IL-1 ligands are expressed in the muscle tissue of myositis patients but also their receptors, both the active (IL-1RI) and the decoy receptor (IL-1RII) form [33]. Both receptors are expressed on endothelial cells and proinflammatory mononuclear cells. Recently, they were also demonstrated to be expressed on muscle fibre membranes and in muscle fibre nuclei [33], indicating that IL-1 could have effects directly on the muscle fibre performance and contractility, similarly to what has been demonstrated for TNF [34]. The role of IL-1 in the pathogenesis in myositis is still uncertain. In one case with an anti-synthetase syndrome, treatment with anakinra was successful, supporting a role of IL-1 in some cases with myositis but this still needs to be tested in larger studies [35]. Interestingly, the combination of IL-1β and IL-17 has been shown to induce IL-6 and CCL20 production by myoblasts in an in vitro system, but whether this is also true in an in vivo situation in humans is not known. IL-18, another cytokine in the IL-1 family, was found to be upregulated in muscle tissue in myositis patients compared with healthy controls [36] but its role in disease mechanism is not fully elucidated.

Although TNF has been detected in the muscle tissue of myositis patients and there are associations with TNF gene polymorphism, the effects of TNF-blocking agents have been conflicting. No effect on muscle performance or on the inflammatory infiltrates was found after treatment of refractory myositis cases with infliximab [29]. On the contrary, some patients worsened and, as discussed above, the type I IFN system was activated in some patients [29]. In contrast to this study, the use of etanercept in refractory polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients has resulted in improved motor strength and decreased fatigue [37].

The DNA-binding protein high-mobility box chromosomal protein 1 (HMGB1) is ubiquitously expressed in all eukaryotic nuclei and, when actively released from macrophages/monocytes, has potent proinflammatory effects and induces TNF and IL-1 [38]. When HMGB1 is released from cells undergoing necrosis, it functions as an alarmin that induces a proinflammatory response cascade. We have earlier demonstrated that HMGB1 is expressed with an extranuclear and extracellular expression in the muscle tissue of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis [39]. The expression of HMGB1 decreased after 3 to 6 months with conventional immunosuppressive treatment but it remained with a high expression in muscle fibres and endothelial cells, even when inflammatory cell infiltrates had diminished [39]. This could indicate that HMGB1 has a distinct role in the chronicity of myositis. Recently, we found that HMGB1 is also present early in the disease course in patients with a low degree of inflammation. HMGB1 induced MHC class I in in vitro experiments, suggesting that HMGB1 may be an early inducer of MHC class I and muscle weakness (C. Grundtman, J. Bruton, T. Östberg, D.S. Pisetsky, H. Erlandsson Harris, U. Andersson, H. Westerblad, I.E. Lundberg, unpublished data). The role of HMGB1 in the disease mechanisms of myositis still needs to be determined, but therapies specifically targeting anti-HMGB1 might be promising candidates for future therapies in myositis.

Taken together, the data in regard to muscle tissue of myositis patients demonstrate a complex involvement of the immune system in which both the innate and adaptive immune systems are involved. Some features are common to all myositis patients, suggesting that some mechanisms are shared by the subsets, whereas other features seem to be specific for certain subsets, suggesting that some molecular mechanisms may be more subset-specific. Furthermore, one might speculate that molecular investigations of muscle tissue are important future tools for characterising subsets of patients for selection of different targeted therapies.

B cells and autoantibodies

It appears that the disease is driven, at least partly, by a loss of self-tolerance with the production of autoantibodies. Up to 80% of patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis, but less commonly in patients with inclusion body myositis, have autoantibodies. The most common autoantibodies are antinuclear autoantibodies. Some of the autoantibodies are often found in other inflammatory connective tissue diseases (for example, anti-PMScl, anti-SSA [anti-Ro 52 and anti-Ro 60], and anti-SSB [anti-La], which are called 'myositis-associated autoantibodies'). Other autoantibodies, so-called MSAs, are more specific for myositis, although they may not be found exclusively in myositis but occasionally in other patients (for example, patients with interstitial lung disease [ILD]).

The anti-Jo-1 autoantibody

The most common MSAs are the anti-tRNA synthetases of which the anti-histidyl-tRNA antibody (or anti-Jo-1), found in approximately 20% to 30% of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients, is the most frequent. Anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies are usually present at the time of diagnosis and may even precede the development of myositis symptoms [40]. Moderate correlations between anti-Jo-1 autoantibody titres and clinical indicators of disease activity in myositis, including elevated serum levels of creatine kinase, muscle dysfunction, and articular involvement, have been found [41]. Furthermore, levels of IgG1 anti-Jo-1 have been found to vary in relation to disease activity [40, 42]. Taken together, these observations suggest that anti-Jo-1 antibodies might have a role in disease mechanisms of myositis. Moreover, anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies could be useful measures of disease activity. The anti-Jo-1 autoantibody is associated with a distinct clinical entity known as the antisynthetase syndrome, which will be described below.

An association between anti-Jo-1-positive myositis patients and high serum levels of B cell-activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF) has also been found, supporting a role of B cells in this subset of myositis [43]. However, high BAFF levels were not associated exclusively with anti-Jo-1 antibodies but were also seen in dermatomyositis patients without these autoantibodies, suggesting that different mechanisms may lead to BAFF induction. Since the first observations of B cells in the inflammatory infiltrates in the muscle tissue of dermatomyositis patients, B cells have been suggested to have a role in this subset of myositis [1]. More recently, plasma cell infiltrates have been identified in infiltrates of both polymyositis and inclusion body myositis patients [4]. In addition, immunoglobulin transcripts are among the most abundant of all immune transcripts in all subsets of myositis and these transcripts are produced by the adaptive immune system [4, 44]. Furthermore, analyses of the variable-region gene sequences revealed clear evidence of significant somatic mutation, isotype switching, receptor revision, codon insertion/deletion, and oligoclonal expansion, suggesting that affinity maturation had occurred within the B cell and plasma cell populations [44]. Thus, antigens localised to the muscle could drive a B cell antigen-specific response in all three subsets of myositis. These antigens could be autoantigens or exogenous antigens derived from viruses or other infectious agents; this, however, has not been fully elucidated.

Autoantibodies and lung/muscle involvement

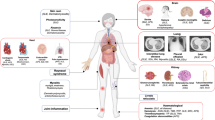

Based on a range of immunologic and immunogenetic data, it appears likely that tRNA synthetases play a direct role in the induction and maintenance of autoimmunity in the antisynthetase syndrome. For example, the antibody response to histidyl-tRNA synthetase undergoes class switching, spectrotype broadening, and affinity maturation, all of which are indicators of a T cell-dependent antigen-driven process [40, 42, 45, 46]. This indicates that a T-cell response directed against histidyl-tRNA synthetase might drive autoantibody formation and tissue damage. The association between autoantibodies directed against RNA-binding antigens and type I IFN activity, as discussed above, further strengthens this hypothesis and suggests a possible mechanism for induction of type I IFN activity in myositis resembling what has been shown in systemic lupus erythematosus patients [47] (Figure 2).

Hypothetical involvement of autoantibodies in myositis. (1) An unknown trigger (for example, a viral infection) can enter the respiratory tract, leading to a modification of histidyl-tRNA synthetase in the lungs and to anti-Jo-1 production (2), which is a common finding in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) (antisynthetase syndrome). When immature dendritic cells (DCs) take up the pathogen (in this case, the histidyl-tRNA synthetase), they are activated and mature into effective antigen-presenting cells. (3–5) Both immature and mature DCs have been found in muscle tissue and skin of myositis patients. Additionally, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs), which are known producers of interferon-alpha (IFN-α), are highly expressed in anti-Jo-1-positive patients and IFN-α can be found in (3) muscle tissue, (4) skin, and (5) circulation of these patents. (5) High levels of both anti-Jo-1 and IFN-α are correlated with disease activity. (6) Autoantigens (histidyl-tRNA synthetase and Mi-2) are expressed in muscle tissue, especially in regenerating fibres. Moreover, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I is also known to be expressed in regenerating fibres and PDCs are often expressed adjacent to MHC class I-positive muscle fibres. (7) High BAFF levels have also been characterised in the circulation of anti-Jo-1-positive patients together with the expression of B cells and plasma cells that possibly could locally produce autoantibodies and function as autoantigen-presenting cells in a subset of patients. Anti-Jo-1, antihistidyl-tRNA synthetase antibody; BAFF, B cell-activating factor of the tumour necrosis factor family. Partly adapted from Servier Medical Art.

The anti-histidyl-tRNA antibodies (anti-Jo-1) are the most common of the antisynthetase autoantibodies and also the most investigated. These autoantibodies are associated with a distinct clinical entity, the antisynthetase syndrome, which is clinically characterised by myositis, ILD, nonerosive arthritis, Raynaud's phenomenon, and skin changes on the hands ('mechanic's hands') [48, 49]. Around 75% of antisynthetase syndrome patients with ILD have anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies compared with 30% of myositis patients without anti-synthetase antibodies. In fact, lung involvement seems to be even more strongly associated with these autoantibodies than muscles, and ILD often precedes myositis symptoms, which raises the possibility of an immune reaction starting in the lungs, possibly after exposure to some environmental factors like viral infections or smoking. A proteolytically sensitive conformation of the histidyl-tRNA synthetase has been demonstrated in lung, which suggests that autoimmunity to histidyl-tRNA synthetase is initiated and propagated in the lung [50]. Moreover, mice immunised with murine Jo-1 develop a striking combination of muscle and lung inflammation that replicates features of the human antisynthetase syndrome [51]. An increased autoantigen expression in muscle tissue has been found to correlate with the differentiation state and myositis autoantigen expression is increased in cells that have features of regenerating muscle cells [52]. Furthermore, we have found a restricted accumulation of T lymphocytes expressing selected T-cell receptor (TCR) V gene segments in the target organ compartments in patients with anti-Jo-1 antibodies (that is, lung and muscle). The occurrence of shared TCR gene segment usage in muscle and lungs could suggest common target antigens in these organs [2].

Taken together, these findings suggest that anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies might function as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune responses, leading to the breakdown of tolerance and an autoimmune destruction of muscle.

Other autoantibodies in myositis

High levels of anti-Mi-2 autoantigen have been found in polymyositis and dermatomyositis muscle lysates and have also been connected with malignancy in dermatomyositis [52]. Anti-Mi-2 autoantibodies are particularly detectable in dermatomyositis patients [53], of whom almost 20% are positive. Anti-Mi-2 autoantibodies are associated with the acute onset of prominent skin changes in patients who respond well to therapy [48, 54]. The newly discovered autoantibody anti-p155 was more often associated with dermatomyositis and paraneoplastic dermatomyositis and its frequency is similarly high in children (29%) and adults (21%) (with a neoplasm 75%) [55]. Whether these autoantibodies have a role in disease mechanisms or are an epiphenomenon needs to be investigated.

Nonimmune mechanisms

The low correlation between the severity of clinical muscle symptoms and inflammation and structural muscle fibre changes indicates that mechanisms other than direct cytotoxic effects on muscle fibres might impair muscle function. Other suggested mechanisms that could play a role in muscle weakness are MHC class I expression on muscle fibres, microvessel involvement leading to tissue hypoxia, and metabolic disturbances. These mechanisms could be induced in several ways and are not solely dependent on immune-mediated pathways, and thus they have been referred to as nonimmune mechanisms [56].

Microvessel involvement

One possible mechanism leading to the impaired muscle function could be a loss of capillaries, which has been reported in dermatomyositis, even in early cases without detectable inflammatory infiltrates [57, 58]. Another observation that supports a disturbed microcirculation in muscle tissue is the morphologically changed endothelial cells resembling high endothelim venules [59]. This phenotype indicates that the endothelial cells are activated. Notably, such phenotypically changed endothelial cells were observed in muscle tissue in newly diagnosed cases, even without detectable inflammatory cell infiltrates.

Capillaries are important for the microenvironment in muscle tissue, for the recirculation of nutrients, as well as for the homing of lymphocytes via an interaction with endothelial cells. Phenotypically altered microvessels might affect the local circulation of the muscle and hence lead to the development of tissue hypoxia and metabolic alterations reported in patients as reduced levels of ATP and phospho-creatine. Myositis patients have an increased endothelial expression of intercellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) [9]. Binding to these molecules enables effector cells to migrate through blood vessel walls. Both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are known to be upregulated by hypoxia, which is also the case for many cytokines that can be found in myositis muscle. Recently, we found that polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients with a short duration of symptoms without inflammation in muscle tissue have a lower number of capillaries, independent of disease subclass, indicating that a loss of capillaries is an early event in both subsets of myositis. The low number of capillaries was associated with increased vascular endothelium growth factor expression in muscle fibres together with increased serum levels. This might indicate a hypoxic state in muscle early in disease before inflammation is detectable in muscle tissue, in both polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients [60].

Major histocompatibility complex class I and endoplasmic reticulum stress

Under physiological conditions, differentiated skeletal muscle fibres do not display MHC class I molecules. However, this is a characteristic finding in myositis [61] and is such a common early finding that its detection has been considered as a diagnostic tool [62]. MHC class I expression in muscle can be induced by several proinflammatory cytokines [63], including HMGB1 (S. Salomonsson, C. Grundtman, S-J. Zhang, J.T. Lanner, C. Li, A. Katz, L.R. Wedderburn, K. Nagaraju, I.E. Lundberg, H. Westerblad, unpublished data). Interestingly, MHC class I itself can mediate muscle weakness in both clinical and experimental settings. For instance, gene transfer of MHC class I plasmids can attenuate muscle regeneration and differentiation [64].

One suggested mechanism for a nonimmune-mediated dysfunction of muscle fibres is the so-called 'endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response'. The folding, exporting, and processing of newly synthesised proteins, including the processing of MHC class I molecules, occur in the ER. ER stress response could be induced as a protective mechanism when newly formed proteins overload the ER (for example, during an infection, hypoxia, or other causes). Two major components of the ER stress response pathway, the unfolded protein response (glucose-regulated protein 78 pathway) and the ER overload response (NF-κB pathway), are highly activated in muscle tissue in both human dermatomyositis and a transgenic MHC class I mouse model [56]. This indicates that MHC class I expression could affect protein synthesis and turnover and thereby hamper muscle contractility. The latter was recently tested on isolated muscles from a transgenic MHC class I mouse model [65], and a reduction in force production in myopathic mice compared to controls was found [66]. This reduction was associated with a decrease in cross-sectional area in extensor digitorum longus muscles (fast-twitch, type II fibres) but due to a decrease in the intrinsic force-generating capacity in soleus muscles (slow-twitch, type I fibres) [66]. The differential effect on fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibres seen in experimental animal myositis resembles the human situation in polymyositis and dermatomyositis, in which patients typically experience more problems with low-force repetitive movements, which mainly depend on oxidative type I muscle fibres, than with single high-force movements in which the contribution of glycogenic fast-twitch fibres is larger.

In regard to this problem, we recently found that chronic patients with a persisting low muscle endurance after immunosuppressive treatment had a low percentage of type I fibres and a corresponding high ratio of type II fibres without any fibre atrophy [67]. Importantly, after 12 weeks of physical exercise, the type I fibre ratio had increased to more normal values [67], albeit muscle performance was still low compared with healthy individuals, which could further indicate some intrinsic effects in type I fibres. The observed low frequency of type I fibres may be seen as an adaptation to a hypoxic environment, as discussed above, and the increased ratio of type I fibres may be a result of a training effect on the microcirculation. The same training program led to further improvement when combined with oral creatine supplement in a placebo-controlled trial [68].

Conclusion

Although the exact pathogenesis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies remains obscure, some scientific endeavors during the past decade have brought us closer to understanding the pathophysiology of these diseases. There are several different molecular pathways that might play a pathogenic role in myositis. The type I IFN activity has been recognised in certain subsets (namely dermatomyositis and anti-Jo-1-positive myositis), and the IL-1 family and HMGB1 are other molecules that are promising potential targets for new therapies as are B cell-blocking agents. But there are also nonimmune pathways that are of importance (that is, a possible acquired metabolic myopathy due to tissue hypoxia or the induction of MHC class I and ER stress). In this context, the safety and benefits of physical training are interesting and there are sufficient scientific data to advocate exercise training as a component of modern treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Another finding characteristic for these diseases is the presence of specific autoantibodies and T cells in muscle tissue, both suggesting that myositis is an autoimmune disorder, although the exact antigen(s) and specificity of the immune reactions are unknown. Moreover, autoantibodies, in particular the MSAs, could be helpful during the diagnostic procedures of myositis and for distinguishing different subsets of myositis with distinct clinical phenotypes and with different molecular pathways. Such differentiation might be useful for future therapeutic decisions and might affect treatment outcome. Thus, it is likely that both immune- and nonimmune-mediated pathways contribute to the impaired muscle function in myositis and this needs to be recognised in the development of new therapeutic modalities.

Note

The Scientific Basis of Rheumatology: A Decade of Progress

This article is part of a special collection of reviews, The Scientific Basis of Rheumatology: A Decade of Progress, published to mark Arthritis Research & Therapy's 10th anniversary.

Other articles in this series can be found at: http://arthritis-research.com/sbr

Abbreviations

- Anti-Jo-1:

-

antihistidyl-tRNA synthetase antibody

- BAFF:

-

B cell-activating factor of the tumour necrosis factor family

- DC:

-

dendritic cell

- ER:

-

endoplasmic reticulum

- HMGB1:

-

high-mobility box chromosomal protein 1

- ICAM-1:

-

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IFN:

-

interferon

- IL:

-

interleukin

- ILD:

-

interstitial lung disease

- MHC:

-

major histocompatibility complex

- MSA:

-

myositis specific autoantibody

- NF-κB:

-

nuclear factor-kappa-B

- PDC:

-

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- TCR:

-

T-cell receptor

- TNF:

-

tumour necrosis factor

- VCAM-1:

-

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.

References

Arahata K, Engel AG: Monoclonal antibody analysis of mononuclear cells in myopathies. I: Quantitation of subsets according to diagnosis and sites of accumulation and demonstration and counts of muscle fibers invaded by T cells. Ann Neurol. 1984, 16: 193-208. 10.1002/ana.410160206.

Englund P, Wahlström J, Fathi M, Rasmussen E, Grunewald J, Tornling G, Lundberg IE: Restricted T cell receptor BV gene usage in the lungs and muscles of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 372-383. 10.1002/art.22293.

Lindberg C, Oldfors A, Tarkowski A: Local T-cell proliferation and differentiation in inflammatory myopathies. Scand J Immunol. 1995, 41: 421-426. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03587.x.

Greenberg SA, Bradshaw EM, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Burleson T, Due B, Bregoli L, O'Connor KC, Amato AA: Plasma cells in muscle in inclusion body myositis and polymyositis. Neurology. 2005, 65: 1782-1787. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187124.92826.20.

Arahata K, Engel AG: Monoclonal antibody analysis of mononuclear cells in myopathies. III: Immunoelectron microscopy aspects of cell-mediated muscle fiber injury. Ann Neurol. 1986, 19: 112-125. 10.1002/ana.410190203.

Goebels N, Michaelis D, Engelhardt M, Huber S, Bender A, Pongratz D, Johnson MA, Wekerle H, Tschopp J, Jenne D, Hohlfeld R: Differential expression of perforin in muscle-infiltrating T cells in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Clin Invest. 1996, 97: 2905-2910. 10.1172/JCI118749.

Salajegheh M, Rakocevic G, Raju R, Shatunov A, Goldfarb LG, Dalakas MC: T cell receptor profiling in muscle and blood lymphocytes in sporadic inclusion body myositis. Neurology. 2007, 69: 1672-1679. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265398.77681.09.

Yamada A, Kishimoto K, Dong VM, Sho M, Salama AD, Anosova NG, Benichou G, Mandelbrot DA, Sharpe AH, Turka LA, Auchincloss H, Sayegh MH: CD28-independent costimulation of T cells in alloimmune responses. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 140-146.

Lundberg I, Kratz AK, Alexanderson H, Patarroyo M: Decreased expression of interleukin-1alpha, interleukin-1beta, and cell adhesion molecules in muscle tissue following corticosteroid treatment in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 336-348. 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<336::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-V.

Bunch TW, Worthington JW, Combs JJ, Ilstrup DM, Engel AG: Azathioprine with prednisone for polymyositis. A controlled, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980, 92: 365-369.

Korotkova M, Barbasso Helmers S, Loell I, Alexanderson H, Grundtman C, Dorph C, Lundberg IE, Jakobsson PJ: Effects of immunosuppressive treatment on microsomal PGE synthase 1 and cyclooxygenases expression in muscle tissue of patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Dec 18., [Epub ahead of print].

Fasth AE, Snir O, Johansson AA, Nordmark B, Rahbar A, Af Klint E, Björkström NK, Ulfgren AK, van Vollenhoven RF, Malmström V, Trollmo C: Skewed distribution of proinflammatory CD4+CD28null T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9: R87-10.1186/ar2286.

Fasth AER, Rahbar A, Dastmalchi M, Söderberg-Nauclér C, Trollmo C, Lundberg IE, Malmström V: Human cytomegalovirus: a possible activator of the immune system in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Am Coll Rheumatol. 2007, Poster 1671.

Hagiwara E, Adams EM, Plotz PH, Klinman DM: Abnormal numbers of cytokine producing cells in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996, 14: 485-491.

Lundberg I, Brengman JM, Engel AG: Analysis of cytokine expression in muscle in inflammatory myopathies, Duchenne dystrophy, and non-weak controls. J Neuroimmunol. 1995, 63: 9-16. 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00122-0.

Lundberg I, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, Andersson U, Klareskog L: Cytokine production in muscle tissue of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 865-874. 10.1002/art.1780400514.

Salomonsson S, Lundberg IE: Cytokines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmunity. 2006, 39: 177-190. 10.1080/08916930600622256.

Greenberg SA, Sanoudou D, Haslett JN, Kohane IS, Kunkel LM, Beggs AH, Amato AA: Molecular profiles of inflammatory myopathies. Neurology. 2002, 59: 1170-1182.

Lepidi H, Frances V, Figarella-Branger D, Bartoli C, Machado-Baeta A, Pellissier JF: Local expression of cytokines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998, 24: 73-79. 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00092.x.

Page G, Chevrel G, Miossec P: Anatomic localization of immature and mature dendritic cell subsets in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: interaction with chemokines and Th1 cytokine-producing cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 199-208. 10.1002/art.11428.

Chevrel G, Page G, Granet C, Streichenberger N, Varennes A, Miossec P: Interleukin-17 increases the effects of IL-1 beta on muscle cells: arguments for the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of myositis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003, 137: 125-133. 10.1016/S0165-5728(03)00032-8.

Greenberg SA, Pinkus GS, Amato AA, Pinkus JL: Myeloid den-dritic cells in inclusion-body myositis and polymyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2007, 35: 17-23. 10.1002/mus.20649.

Nagaraju K, Rider LG, Fan C, Chen YW, Mitsak M, Rawat R, Patterson K, Grundtman C, Miller FW, Plotz PH, Hoffman E, Lundberg IE: Endothelial cell activation and neovascularization are prominent in dermatomyositis. J Autoimmune Dis. 2006, 3: 2-10.1186/1740-2557-3-2.

Eloranta ML, Barbasso Helmers S, Ulfgren AK, Ronnblom L, Alm GV, Lundberg IE: A possible mechanism for endogenous activation of the type I interferon system in myositis patients with anti-Jo-1 or anti-Ro 52/anti-Ro 60 autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 3112-3124. 10.1002/art.22860.

Greenberg SA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Burleson T, Sanoudou D, Tawil R, Barohn RJ, Saperstein DS, Briemberg HR, Ericsson M, Park P, Amato AA: Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol. 2005, 57: 664-678. 10.1002/ana.20464.

McNiff JM, Kaplan DH: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions in a pattern distinct from lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2008, 35: 452-456. 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00848.x.

Baechler EC, Bauer JW, Slattery CA, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, Novitzke J, Ytterberg SR, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW, Reed AM: An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Mol Med. 2007, 13: 59-68. 10.2119/2006-00085.Baechler.

Walsh RJ, Kong SW, Yao Y, Jallal B, Kiener PA, Pinkus JL, Beggs AH, Amato AA, Greenberg SA: Type I interferon-inducible gene expression in blood is present and reflects disease activity in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 3784-3792. 10.1002/art.22928.

Dastmalchi M, Grundtman C, Alexanderson H, Mavragani CP, Einarsdottir H, Barbasso Helmers S, Elvin K, Crow MK, Nennesmo I, Lundberg IE: A high incidence of disease flares in an open pilot study of infliximab in patients with refractory inflammatory myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Feb 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Mavragani CP, Niewold TB, Moutsopoulos NM, Pillemer SR, Wahl SM, Crow MK: Augmented interferon-alpha pathway activation in patients with Sjogren's syndrome treated with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 3995-4004. 10.1002/art.23062.

Englund P, Nennesmo I, Klareskog L, Lundberg IE: Interleukin-1alpha expression in capillaries and major histocompatibility complex class I expression in type II muscle fibers from polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients: important pathogenic features independent of inflammatory cell clusters in muscle tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 1044-1055. 10.1002/art.10140.

Nyberg P, Wikman AL, Nennesmo I, Lundberg I: Increased expression of interleukin 1alpha and MHC class I in muscle tissue of patients with chronic, inactive polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 940-948.

Grundtman C, Salomonsson S, Dorph C, Bruton J, Andersson U, Lundberg IE: Immunolocalization of interleukin-1 receptors in the sarcolemma and nuclei of skeletal muscle in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 674-687. 10.1002/art.22388.

Reid MB, Lannergren J, Westerblad H: Respiratory and limb muscle weakness induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha: involvement of muscle myofilaments. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 479-484. 10.1164/rccm.2202005.

Furlan A, Botsios C, Ruffatti A, Todesco S, Punzi L: Antisynthetase syndrome with refractory polyarthritis and fever successfully treated with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra: a case report. Joint Bone Spine. 2008, 75: 366-367. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.07.010.

Tucci M, Quatraro C, Dammacco F, Silvestris F: Interleukin-18 overexpression as a hallmark of the activity of autoimmune inflammatory myopathies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006, 146: 21-31. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03180.x.

Efthimiou P, Schwartzman S, Kagen LJ: Possible role for tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of resistant dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a retrospective study of eight patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 1233-1236. 10.1136/ard.2005.048744.

Andersson U, Wang H, Palmblad K, Aveberger AC, Bloom O, Erlandsson-Harris H, Janson A, Kokkola R, Zhang M, Yang H, Tracey KJ: High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 2000, 192: 565-570. 10.1084/jem.192.4.565.

Ulfgren AK, Grundtman C, Borg K, Alexanderson H, Andersson U, Harris HE, Lundberg IE: Down-regulation of the aberrant expression of the inflammation mediator high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in muscle tissue of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis treated with corticosteroids. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 1586-1594. 10.1002/art.20220.

Miller FW, Waite KA, Biswas T, Plotz PH: The role of an autoantigen, histidyl-tRNA synthetase, in the induction and maintenance of autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87: 9933-9937. 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9933.

Stone KB, Oddis CV, Fertig N, Katsumata Y, Lucas M, Vogt M, Domsic R, Ascherman DP: Anti-Jo-1 antibody levels correlate with disease activity in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 3125-3131. 10.1002/art.22865.

Miller FW, Twitty SA, Biswas T, Plotz PH: Origin and regulation of a disease-specific autoantibody response. Antigenic epitopes, spectrotype stability, and isotype restriction of anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1990, 85: 468-475. 10.1172/JCI114461.

Krystufkova O, Vallerskog T, Barbasso Helmers S, Mann H, Pùtová I, Belácek J, Malmström V, Trollmo C, Vencovsky J, Lundberg IE: Increased serum levels of B-cell activating factor (BAFF) in subsets of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jul 15 [Epub ahead of print].

Bradshaw EM, Orihuela A, McArdel SL, Salajegheh M, Amato AA, Hafler DA, Greenberg SA, O'Connor KC: A local antigen-driven humoral response is present in the inflammatory myopathies. J Immunol. 2007, 178: 547-556.

Martin A, Shulman MJ, Tsui FW: Epitope studies indicate that histidyl-tRNA synthetase is a stimulating antigen in idiopathic myositis. FASEB J. 1995, 9: 1226-1233.

Raben N, Nichols R, Dohlman J, McPhie P, Sridhar V, Hyde C, Leff R, Plotz P: A motif in human histidyl-tRNA synthetase which is shared among several aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is a coiled-coil that is essential for enzymatic activity and contains the major autoantigenic epitope. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269: 24277-24283.

Lovgren T, Eloranta ML, Kastner B, Wahren-Herlenius M, Alm GV, Ronnblom L: Induction of interferon-alpha by immune complexes or liposomes containing systemic lupus erythematosus autoantigen- and Sjogren's syndrome autoantigen-associated RNA. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 1917-1927. 10.1002/art.21893.

Love LA, Leff RL, Fraser DD, Targoff IN, Dalakas M, Plotz PH, Miller FW: A new approach to the classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: myositis-specific autoantibodies define useful homogeneous patient groups. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991, 70: 360-374.

Marguerie C, Bunn CC, Beynon HL, Bernstein RM, Hughes JM, So AK, Walport MJ: Polymyositis, pulmonary fibrosis and autoantibodies to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase enzymes. Q J Med. 1990, 77: 1019-1038.

Levine SM, Raben N, Xie D, Askin FB, Tuder R, Mullins M, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen LA: Novel conformation of histidyltransfer RNA synthetase in the lung: the target tissue in Jo-1 autoanti-body-associated myositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 2729-2739. 10.1002/art.22790.

Katsumata Y, Ridgway WM, Oriss T, Gu X, Chin D, Wu Y, Fertig N, Oury T, Vandersteen D, Clemens P, Camacho CJ, Weinberg A, Ascherman DP: Species-specific immune responses generated by histidyl-tRNA synthetase immunization are associated with muscle and lung inflammation. J Autoimmun. 2007, 29: 174-186. 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.005.

Casciola-Rosen L, Nagaraju K, Plotz P, Wang K, Levine S, Gabrielson E, Corse A, Rosen A: Enhanced autoantigen expression in regenerating muscle cells in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Exp Med. 2005, 201: 591-601. 10.1084/jem.20041367.

Brouwer R, Hengstman GJ, Vree Egberts W, Ehrfeld H, Bozic B, Ghirardello A, Grøndal G, Hietarinta M, Isenberg D, Kalden JR, Lundberg I, Moutsopoulos H, Roux-Lombard P, Vencovsky J, Wikman A, Seelig HP, van Engelen BG, van Venrooij WJ: Autoantibody profiles in the sera of European patients with myositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001, 60: 116-123. 10.1136/ard.60.2.116.

Hengstman GJ, Vree Egberts WT, Seelig HP, Lundberg IE, Moutsopoulos HM, Doria A, Mosca M, Vencovsky J, van Venrooij WJ, van Engelen BG: Clinical characteristics of patients with myositis and autoantibodies to different fragments of the Mi-2 beta antigen. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 242-245. 10.1136/ard.2005.040717.

Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, Perurena O, Koneru B, O'Hanlon TP, Miller FW, Rider LG, Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Study Group; International Myositis Collaborative Study Group: A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 3682-3689. 10.1002/art.22164.

Nagaraju K, Casciola-Rosen L, Lundberg I, Rawat R, Cutting S, Thapliyal R, Chang J, Dwivedi S, Mitsak M, Chen YW, Plotz P, Rosen A, Hoffman E, Raben N: Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in autoimmune myositis: potential role in muscle fiber damage and dysfunction. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 1824-1835. 10.1002/art.21103.

Emslie-Smith AM, Engel AG: Microvascular changes in early and advanced dermatomyositis: a quantitative study. Ann Neurol. 1990, 27: 343-356. 10.1002/ana.410270402.

Kissel JT, Mendell JR, Rammohan KW: Microvascular deposition of complement membrane attack complex in dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1986, 314: 329-334.

Girard JP, Springer TA: High endothelial venules (HEVs): specialized endothelium for lymphocyte migration. Immunol Today. 1995, 16: 449-457. 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80023-9.

Grundtman C, Tham E, Ulfgren A-K, Lundberg IE: Vascular endothelium growth factor is highly expressed in muscle tissue of patients with polymyositis and patients with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 58: in press.

Karpati G, Pouliot Y, Carpenter S: Expression of immunoreactive major histocompatibility complex products in human skeletal muscles. Ann Neurol. 1988, 23: 64-72. 10.1002/ana.410230111.

Civatte M, Schleinitz N, Krammer P, Fernandez C, Guis S, Veit V, Pouget J, Harlé JR, Pellissier JF, Figarella-Branger D: Class I MHC detection as a diagnostic tool in noninformative muscle biopsies of patients suffering from dermatomyositis (DM). Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003, 29: 546-552. 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00471.x.

Nagaraju K, Raben N, Villalba ML, Danning C, Loeffler LA, Lee E, Tresser N, Abati A, Fetsch P, Plotz PH: Costimulatory markers in muscle of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and in cultured muscle cells. Clin Immunol. 1999, 92: 161-169. 10.1006/clim.1999.4743.

Pavlath GK: Regulation of class I MHC expression in skeletal muscle: deleterious effect of aberrant expression on myogenesis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002, 125: 42-50. 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00026-7.

Nagaraju K, Raben N, Loeffler L, Parker T, Rochon PJ, Lee E, Danning C, Wada R, Thompson C, Bahtiyar G, Craft J, Hooft Van Huijsduijnen R, Plotz P: Conditional up-regulation of MHC class I in skeletal muscle leads to self-sustaining autoimmune myositis and myositis-specific autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 9209-9214. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9209.

Salomonsson S, Grundtman C, Zhang S-J, Lanner JT, Li C, Katz A, Wedderburn LR, Nagaraju K, Lundberg IE, Westerblad H: Up-regulation of MHC class I in tansgenic mice results in reduced force-generating capacity in slow-twitch muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2008, in press

Dastmalchi M, Alexanderson H, Loell I, Ståhlberg M, Borg K, Lundberg IE, Esbjörnsson M: Effect of physical training on the proportion of slowtwitch type I muscle fibers, a novel nonimmune-mediated mechanism for muscle impairment in polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57: 1303-1310. 10.1002/art.22996.

Chung YL, Alexanderson H, Pipitone N, Morrison C, Dastmalchi M, Ståhl-Hallengren C, Richards S, Thomas EL, Hamilton G, Bell JD, Lundberg IE, Scott DL: Creatine supplements in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies who are clinically weak after conventional pharmacologic treatment: six-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57: 694-702. 10.1002/art.22687.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Schering-Plough, Nordic Biotech to Dr Ingrid E Lundberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

IEL has a small number of stock shares in Pfizer AB.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lundberg, I.E., Grundtman, C. Developments in the scientific and clinical understanding of inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Res Ther 10, 220 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2501

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2501