Abstract

Data from population- and clinic-based epidemiologic studies of rheumatoid arthritis patients suggest that individuals with rheumatoid arthritis are at risk for developing clinically evident congestive heart failure. Many established risk factors for congestive heart failure are over-represented in rheumatoid arthritis and likely account for some of the increased risk observed. In particular, data from animal models of cytokine-induced congestive heart failure have implicated the same inflammatory cytokines produced in abundance by rheumatoid synovium as the driving force behind maladaptive processes in the myocardium leading to congestive heart failure. At present, however, the direct effects of inflammatory cytokines (and rheumatoid arthritis therapies) on the myocardia of rheumatoid arthritis patients are incompletely understood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unique cardiac complications of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), such as cardiac rheumatoid nodules, have been recognized for over a century. It has only been appreciated in the last decades, however, that certain chronic autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as RA and systemic lupus erythematosis, increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), particularly atherosclerosis and congestive heart failure (CHF) [1–5]. In fact, striking commonalities in the cellular and cytokine profiles of the rheumatoid synovial lesion and atherosclerotic plaque [6–8] have prompted speculation that the inflammatory pathways of RA may initiate and/or accelerate plaque formation and that this effect may be ameliorated by anti-inflammatory therapies [9].

The link between RA and CHF is less well studied. The CHF phenotype can evolve from a variety of pathogenic conditions, many of which may be promoted by the RA disease process. Yet to date, only a handful of investigations have attempted to dissect this complex issue. A particular source of confusion has been the apparent contradiction between pre-clinical studies linking inflammation to CHF and the lack of efficacy of anti-cytokine therapy in clinical trials in advanced CHF (discussed below). Because anti-cytokine therapy has become a cornerstone in the treatment of RA, it is particularly critical to understand the contribution of cytokine-induced inflammation to myocardial structure and function in RA. Here, we review the current literature on the epidemiology of CHF in RA with an emphasis on the pathogenesis of cytokine induced myocardial dysfunction.

Epidemiology of congestive heart failure: general considerations

The epidemiology of CHF in RA, and the limitations of the available data, are better appreciated in the context of estimates of CHF in the general population. The prevalence of CHF in western countries appears to have been increasing over the past few decades, due primarily to increased longevity rather than to a change in incidence rates [10]. In the United States, more than 400,000 new cases of CHF are identified each year and added to the estimated 2.5 to 5 million Americans with prevalent CHF [11, 12], yielding an overall prevalence of 1.1% to 2% of the population. Nearly 300,000 deaths in the US are attributed to CHF annually [10]. For persons over the age of 65 years, CHF is the most frequent cause of hospitalization [11, 13].

Incidence rates of CHF vary among published reports, presumably reflecting differences in the populations studied, diagnostic criteria used, and temporal trends in coding practices for reimbursement [14]. Recent data from several community-based cohorts [15–18] have yielded an estimated age-adjusted incidence of CHF of 3.4 to 17.6 per 1,000 person-years for men and 2.4 to 12.5 per 1,000 person-years for women. The wide range in rates reflects, at least in part, differences in diagnostic criteria used from study to study. For example, age-adjusted incidence rates based on the Framingham diagnostic criteria for heart failure [15, 16, 18, 19] (Table 1) were between 2 and 4 per 1,000 person-years, whereas rates based on less stringent criteria were three- to four-fold higher [17].

The incidence of CHF increases with age [20, 21]; 88% of affected individuals are over the age of 65 years, and 49% are over 80 years at diagnosis [20]. The remaining lifetime risk of developing CHF at all index ages from 40 through 80 years of age is between 20% and 33%, and is roughly equal for men and women [17, 22]. Levy et al. [15] have shown that over the past 50 years the incidence of CHF has declined among women but not among men. This lack of decline in CHF incidence among men is largely attributable to advances in the management of acute myocardial infarction, diabetes, and hypertension that have led to an overall decrease in mortality rates from these disorders while adding to the incidence of CHF [23]. Survival after the onset of CHF has improved in both sexes [15]. Factors contributing to the decrease in CHF mortality include improved access to care, the introduction of effective therapies, and improved care of comorbid conditions [15]. Despite these encouraging trends, mortality rates of patients with CHF remain alarmingly high. Recent reports from community-based cohorts [15–18] estimate age-adjusted one- and five-year CHF mortality at 23% to 27% and 45% to 65%, respectively. For women in these series, survival was slightly better than [15, 16] or equal to [17, 18] men.

Epidemiology of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis

Fewer statistics on incidence and prevalence rates for CHF in patients with RA are available and are derived from a handful of population-based [24–26] and clinic-based RA cohorts [5, 27, 28]. Gabriel et al. [24] estimated the incidence of CHF among all RA patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from data abstracted from medical records. Between 1955 and 1985, 78 cases of incident CHF were identified among 450 prevalent cases of RA compared to 54 cases among the same number of non-RA community controls matched for age, sex, and baseline comorbidity, yielding a relative risk of 1.60 (95% CI 1.12–2.27). In contrast, the risk of incident CHF in patients with osteoarthritis (OA), a non-inflammatory arthritis, was not increased compared to non-OA community controls [24]. In a follow-up retrospective review of the same cohort extended to 1995, now using the Framingham diagnostic criteria for CHF (Table 1), Nicola et al. [26] confirmed an increased risk of incident CHF in both rheumatoid factor (RF) negative and positive RA patients (hazards ratio 1.34 and 2.29, respectively) compared to non-RA controls adjusted for age, sex, and CV risk factors. Incident CHF risk remained elevated after further adjustment for comorbid ischemic heart disease (hazards ratio 1.28 and 2.59 for RF negative and positive RA patients, respectively), although the risk relationship was no longer statistically significant for RF negative patients in this model [26].

In a combined cohort of RA patients from community-based practices and drug safety monitoring studies (n = 9093), Wolfe et al. [5] estimated an adjusted lifetime relative risk of CHF in patients with RA of 1.43 (95% CI 1.24–1.33) compared with OA controls. The adjusted lifetime prevalence of CHF in the RA population was 2.34% compared to 1.64% in OA controls. Data were collected via patient survey of self-reported, physician-diagnosed CHF, and confirmed by review of a random sample of medical records in 50% of patients reporting CVD events. In a subsequent analysis [27], in which the drug safety cohort represented a third (n = 4,307) of the total sample (n = 13,171), Wolfe et al. reported an adjusted frequency of CHF of 3.9% (95% CI 3.4–4.3%) in RA patients compared to 2.3% (95% CI 1.6–3.3%) in controls with knee or hip OA. Factors associated with prevalent and incident CHF were those typically associated with CHF in the non-RA population (e.g., age, male gender, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and smoking) while RA-related measures (patient-reported disability, pain, and RA global severity) were also associated with prevalent and incident CHF. As data were collected by mailed questionnaire, objective measures of RA disease activity (e.g., swollen and tender joint counts and serum inflammatory markers) were not available to assess as predictor variables.

Indeed, the impact of CHF in RA may be under-appreciated due to excess CHF related mortality. Mutru et al. [28] first reported a higher rate of CHF-attributed mortality in RA patients compared to age- and gender-matched controls with CHF for both males (P = 0.004) and females (P = 0.042). In a recent report, Nicola et al. [29] found that CHF preceded nearly two-thirds of the excess CVD associated deaths in RA patients compared to age- and gender-matched controls. These unexpected results alone emphasize a need for greater understanding of the dynamics of myocardial dysfunction in RA and suggest that survivor-bias may serve to underestimate the true extent of CHF in the RA population.

An important limitation of each of these studies is in the method chosen to ascertain the diagnosis of CHF. The application of clinical criteria alone for the diagnosis of CHF is too imprecise, as demonstrated by one study [30] in which a false positive diagnosis of CHF was made by primary care providers in over one-third of patients. Current guidelines [10] advocate the need for Doppler echocardiographic confirmation of any diagnosis of CHF when suspected clinically. Reliance on clinical diagnostic criteria alone may result in over-diagnosis of CHF in some case. In others, CHF may be under-diagnosed when dependent ankle edema is mistaken for joint swelling, chronic pulmonary congestion is misinterpreted as rheumatoid lung involvement, and exertional dyspnea is masked by a sedentary lifestyle due to painful joint deformities. Nevertheless, on balance, the available data support higher prevalence and incidence rates of CHF in RA patients compared to matched controls without RA. Many factors unique to or over-represented in RA patients may explain, at least in part, why the myocardium is at risk in RA. In addition, an analysis of the relative contributions of each of these risk factors and associated biomarkers to the development of CHF in RA patients invites speculation into the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to myocardial dysfunction.

Risk factors, echocardiographic predictors, and biochemical markers associated with the development of CHF: relationship to RA

Risk factors for congestive heart failure

The risk factors and biochemical markers associated with the development of CHF in the general population are listed in Table 2. Although no systematic investigation has been performed to dissect the relative contribution of each of these factors to the development of CHF in RA, several well-defined contributing factors have been shown to be over-represented in RA. Whether the increased risk of CHF in RA is primarily due to the effects of known risk factors, or to unidentified risk factors unique to RA, is currently unknown, though the predictors analyses by Wolfe et al. [27] and Nicola et al. [26] (discussed above) suggest that both traditional and RA-specific risk factors for CHF are operative. The available evidence on the prevalence of some of these important risk factors for CHF in RA is reviewed below, though it is important to recognize that RA is a heterogeneous disorder, and some factors may represent different risks for different subpopulations of RA patients.

Hypertension

Systemic hypertension is one of the most potent risk factors for CHF, conferring a two- to three-fold increase in CHF risk for affected individuals [31]. Chronic hypertension promotes the development of CHF by a variety of mechanisms, including the induction of maladaptive myocardial remodeling and atherosclerosis. Reports of the prevalence of hypertension in RA have yielded varied results, with authors reporting lower [32], equivalent [26, 33, 34], or elevated [3, 24, 35] mean systolic and/or diastolic blood pressures in RA patients compared to matched controls. Importantly, although any history of hypertension was strongly associated with prevalent CHF in the study by Wolfe et al. [27] (odds ratio 2.6 (95% CI 2.1–3.2)), Nicola et al. [26] found no association between hypertension and risk of incident CHF in RA patients followed for a median of 11.8 years.

Additionally, other factors over-represented in RA patients, such as the chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids, are both known to promote fluid retention and elevate systemic blood pressure [36]. The independent effect of these agents on the development of CHF in RA is complex, however, and has yet to be directly investigated.

Coronary atherosclerosis/myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the most potent risk factor for CHF, with a population-attributed risk for the development of CHF in the Framingham cohort of 34% for men and 13% for women [31]. In most cases, other risk factors for CHF (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and smoking) also contribute to the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis. Importantly, unrecognized and silent MI represents up to 25% of all myocardial ischemic events [37] and subclinical atherosclerosis (with no history of MI) is also associated with an increased risk for the development of CHF [38].

Several studies have confirmed an approximately two- to four-fold increase in risk for MI among RA patients compared to non-RA controls [3, 5, 34]. Wolfe et al. [27] showed that recent MI (within six months) and any history of MI were both significant univariate correlates of prevalent CHF in RA patients (odds ratio 16.1 (95% CI 11.0–23.7) and 6.6 (95% CI 5.4–8.0), respectively). In the study by Nicola et al. [26], ischemic heart disease (including overt MI, silent MI, and angina) and risk factors for CVD accounted for the risk of incident CHF in RF negative, but not RF positive, RA patients.

Subclinical atherosclerosis, as measured by carotid ultrasound, is more prevalent in RA patients compared to matched controls [39]. However, the relationship of subclinical atherosclerosis to the risk of CHF (in the absence of clinically recognized ischemic heart disease) in RA patients is currently unknown.

Diabetes

Although diabetes is a well-recognized risk factor for the development of CHF [40, 41], the prevalence of diabetes does not appear to be increased in RA patients compared to non-RA controls [24, 42]. Glucose intolerance/peripheral insulin resistance has, however, been associated with an increase in CHF risk in both cross-sectional [43] and prospective, population-based [40] studies, and may be increased in RA [44, 45]

Valvular heart disease

Hemodynamically significant cardiac valvular disease may lead to overt CHF through maladaptive compensatory mechanisms resulting in myocardial remodeling (the molecular basis of which is discussed below). Both necropsy [46] and cross-sectional echocardiographic studies [47] of RA hearts have identified an increased prevalence of granulomatous and non-granulomatous valvular abnormalities, particularly of the mitral valve, and an increased prevalence of mitral regurgitation in RA patients compared to matched non-RA controls. No longitudinal echocardiographic studies have been performed, however, to determine the impact of this finding on the subsequent risk for developing CHF in affected RA patients. Destructive valvular lesions leading to complete valvular incompetence have been reported [48, 49] but are considered rare occurrences.

Intrinsic pulmonary disease

A wide spectrum of intrinsic pulmonary disorders, including disorders of the pulmonary air-spaces (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), parenchyma (interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis), and vasculature (primary pulmonary hypertension) are associated with increasing pulmonary vascular resistance, progressive hypertrophy of the right ventricle, and eventual right heart failure with clinical CHF [50]. In RA, pulmonary disease may be a manifestation of the RA disease process itself or a result of RA-directed therapies (methotrexate, D-penicillamine, gold and others) [51]. While symptomatic chronic pulmonary diseases are more prevalent in RA patients compared with non-RA controls [24, 52], subclinical pulmonary disease, including airways disease [53] (bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis) and parenchymal disease (interstitial pneumonitis), have been noted in nearly 50% of unselected RA patients in one series [54]. In addition, several echocardiographic studies have suggested higher right ventricular systolic pressures in RA patients compared to non-RA controls [55–57]. In the study by Dawson et al. [56], pulmonary parenchymal disease could only account for 6% of RA cases with increased pulmonary arterial pressures, suggesting that asymptomatic primary pulmonary vascular disease may be under-appreciated in RA. These findings, and their putative effect on the subsequent development of CHF, warrant further study.

Sleep apnea/sleep-disordered breathing

Although sleep apnea has been shown to be highly prevalent in people with CHF in cross-sectional studies [58], no prospective population-based studies, to date, have investigated the putative effect of sleep apnea on the risk of CHF. Sleep apnea is known, however, to increase systemic blood pressure via hypoxia-induced activation of the sympathetic nervous system [59], increase right ventricular pressure via hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction [60], potentiate hypoxia-induced coronary ischemia [61], and induce the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [62], all recognized contributors to CHF risk. Few studies of sleep apnea in RA exist, though the disorder has been reported in RA in the context of cervical spine and temporomandibular joint involvement [63]. Recent reports of substantial improvements in sleep apnea-associated daytime somnolence in patients treated with TNF inhibitors [64, 65] suggests that the problem may be under-appreciated in RA. At present, however, any link between sleep apnea and CHF risk in RA is speculative.

Other factors

Smoking and obesity are established risk factors for both RA [66] and CHF [41, 67]. Both are thought to promote CHF primarily through exacerbation of atherogenesis, though both may also potentiate the release of agents with direct toxicity to the myocardium itself [68, 69]. Interestingly, although RA patients may have similar or lower body mass indices than non-RA counterparts, loss of skeletal muscle mass accompanied by a compensatory increase in total fat mass in RA patients may account for the stability of body mass indices [70]. Though no focused investigations have been undertaken to date, this condition, termed sarcopenic obesity, could predispose RA patients to higher than expected CHF risk.

Rheumatoid arthritis associated factors

In general, myocardial nodules, restrictive pericarditis, and coronary vasculitis are exceedingly rare causes of CHF [71]; however, older necropsy studies of RA hearts [32, 46, 72] have indicated a higher prevalence of each of these complications compared to the hearts of autopsied non-RA patients. More recent series using transthoracic echocardiography [55, 56] have identified a much lower prevalence of pericarditis than that reported in the autopsy studies (2% versus 29% to 40%). In a series using transesophageal echocardiography [47], however, thirteen percent of RA patients were found to have clinically silent pericarditis versus zero percent of non-RA controls. Case reports of rheumatoid nodules [73, 74], restrictive pericarditis [75, 76], and coronary vasculitis [77] in RA patients resulting in CHF are not uncommon in the literature, although it is likely that these entities account for only a small portion of the excess cases of CHF in RA.

Echocardiographic predictors of congestive heart failure

Several large prospective studies have identified asymptomatic left ventricular (LV) enlargement, hypertrophy and dysfunction as significant risk factors for the development of CHF [78–80]. The strength of these associations, combined with the documented efficacy of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in delaying disease progression, have prompted consensus recommendation of medical treatment for these conditions classified as subclinical stages of CHF [81]. Importantly, once global alterations of LV architecture and function are established, progression to CHF with functional deterioration and eventually death is inexorable [82]. This unfavorable evolution highlights the need to define earlier stages of myocardial dysfunction, particularly in individuals with known risk factors for CHF.

CHF with preserved systolic function

Between 30% and 50% of patients with CHF have preserved systolic function (defined as LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 45–50%) [83, 84]. Despite the fact that this condition is associated with lower mortality when compared to heart failure with reduced LVEF, patients with CHF and normal LVEF have a four-fold increase in mortality relative to the normal population [83]. In asymptomatic individuals, diastolic dysfunction with preserved systolic function is also predictive of the subsequent development of overt CHF [85].

To date, a number of Doppler echocardiographic studies have been performed in RA patients without clinical evidence of CHF [55, 86–94] (Table 3). Although limited by small numbers of patients and, in some cases, failure to provide a non-RA comparator group, these studies are consistent in demonstrating a high prevalence of asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction in the setting of generally preserved systolic function. A correlation between the degree of diastolic dysfunction and RA disease duration was shown in several investigations [92, 94]. Without longitudinal assessments, however, few conclusions can be made about the long-term effects of RA disease activity on cardiac structure and function or, more importantly, factors influencing the transition from asymptomatic myocardial dysfunction to clinical CHF in RA.

Impaired diastolic filling is felt to relate physiologically to impairment in relaxation or compliance of the left ventricle, resulting in elevated LV filling pressures and resultant elevated back pressures through the pulmonary circulation, right heart, and beyond [95]. Histologically, processes that tend to stiffen the myocardium (e.g., hypertrophy, fibrosis, or infiltrative diseases) or reduce compliance (e.g., restrictive pericarditis) can manifest as diastolic dysfunction. We postulate that chronic low-grade myocardial inflammation resulting in fibrosis may predispose patients with RA to diastolic dysfunction (discussed below).

The limitations of standard echocardiography, which include poor endocardial definition, lack of inter-observer reproducibility of ejection fraction estimates, and lack of standardization of diagnostic criteria for diastolic dysfunction [96], often make it difficult to be precise about the diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction. In practice, however, the diagnosis of diastolic CHF is generally based on the finding of typical symptoms and signs of CHF in a patient who is shown to have a normal LVEF and no valvular abnormalities on echocardiography [84]. Newer noninvasive imaging methods, including contrast echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, have been developed that permit greater precision and accuracy in the assessment of myocardial function. Accordingly, the incorporation of these newer imaging modalities into studies exploring CHF in RA may not only serve to improve diagnostic accuracy, but also provide predictive power and insights into the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of disease.

Biomarkers associated with congestive heart failure risk

Cardiac natriuretic hormones

Recently, the measurement of circulating levels of brain natriuretic peptide has become available as a means of identifying patients with elevated LV filling pressures who are likely to exhibit signs and symptoms of CHF. Although the role of cardiac natriuretic hormones in the identification and management of individuals with asymptomatic ventricular dysfunction remains to be fully clarified [97], elevated serum levels of brain natriuretic peptide and amino-terminal pro-atrial natriuretic peptide have been associated with an increased risk of subsequent CHF in a community-based epidemiologic study [98]. In one small-scale cross-sectional study, RA patients were found to have higher serum atrial natriuretic peptide levels than healthy, non-RA controls [99]. Another cross-sectional study suggested that brain natriuretic peptide levels may be elevated in RA patients independent of overt or subclinical myocardial dysfunction [100]. To date, no studies have been performed in RA patients to establish the role of cardiac natriuretic hormones in either risk stratification or diagnosis of CHF.

Hyperhomocysteinemia

Elevated serum levels of homocysteine have been independently linked to an increased risk of CHF [101], particularly in women [102]. Hyperhomocysteinemia may promote the development of CHF through induction of atherosclerosis [103] and by direct effects on the myocardium leading to myocardial remodeling [102] (discussed below). In RA patients, homocysteine levels have been shown to be significantly higher than those of matched non-RA controls [104] and are associated with both markers of inflammation and therapy with methotrexate [105]. Though folic acid treatment reduces homocysteine levels in RA patients [105], and combination therapy with methotrexate and folic acid has been recently shown to be associated with a reduced incidence of CVD in veterans with RA [106], the complex relationship of RA-induced and RA therapy-induced hyperhomocysteinemia to CHF risk in RA has yet to be completely elucidated.

Inflammatory cytokines

In patients with overt CHF, levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and/or TNF-α receptors) are elevated and correlate with the severity of the disease [107–112] regardless of etiology of CHF. In patients with no overt CHF or history of ischemic heart disease, those with the highest serum levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), and peripheral-blood mononuclear cell TNF-α were shown to have a two- to four-fold higher risk of developing CHF compared to patients with the lowest baseline levels of these cytokines [113, 114]. In patients with overt CHF, both circulating peripheral-blood mononuclear cells and cells localized to the myocardium, including infiltrating inflammatory cells and cardiac myocytes, have been shown to be the source of the elevated cytokine levels [112, 115, 116].

In the inflamed synovium of the rheumatoid joint, macrophage-derived cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 are prominently expressed, and inhibitors of these cytokines, particularly TNF inhibitors, have been proven to be highly successful therapies for RA [117–120]. In RA, the inflamed synovium as well as peripheral-blood mononuclear cells contribute to elevated circulating TNF-α (and TNF receptor) levels. To date, however, the potential contribution of the myocardium in RA as a source of local cytokine production has not been investigated.

Other conditions associated with chronically elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., aging, chronic kidney disease, obesity) are also associated with an increased prevalence of CHF [121, 70]; however, as in RA, the contributions of various non-inflammatory confounders in each of these conditions to the pathogenesis of CHF have not been fully explored.

Clinical studies of TNF inhibitors and congestive heart failure

The potent association of inflammatory cytokines with both CHF risk and clinical worsening of existing CHF has prompted speculation that pharmacologic cytokine inhibition might prove an effective treatment for established symptomatic CHF and/or reduce the risk of developing CHF in patients who are potentially at risk for CHF secondary to chronic cytokine excess (i.e., patients with RA and other chronic systemic inflammatory disorders). The unfavorable and unanticipated results of clinical trials investigating the use of anti-TNF-α therapy to treat advanced CHF, however, have raised concerns that TNF inhibitors may actually be harmful to the myocardium. To address this apparent contradiction we next examine the conflicting human clinical experience relating TNF inhibitors to CHF in the context of the available animal data on cytokine-induced CHF.

Use of TNF inhibitors as a treatment for advanced congestive heart failure

Both etanercept, a soluble decoy TNF receptor, and infliximab, a chimeric anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, have undergone efficacy and safety evaluations in multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials for the treatment of patients with advanced symptomatic CHF [122, 123]. The study designs of these trials ('RENNAISSANCE' (Randomized Etanercept North American Strategy To Study Antagonism Of Cytokines) and 'RECOVER' (Research Into Etanercept: Cytokine Antagonism In Ventricular Dysfunction Trial) [123] for etanercept, and 'ATTACH' (Anti-TNF-α Therapy Against Chronic Heart Failure) [122] for infliximab) have been recently reviewed in detail [124]. The collective results of the trials were generally unfavorable, with RENNAISSANCE and RECOVER halted in June 2001 when an interim analysis revealed that continuation would be highly unlikely to show a statistically significant difference in outcomes between the treatment groups [123] and ATTACH demonstrating no clinical efficacy of infliximab, but higher rates of hospitalizations and all-cause mortality in patients treated with the highest dose (10 mg/kg) of infliximab compared to placebo [122].

The high-profile and well-publicized nature of these trials, coupled with a 2002 report, using the US Food and Drug Administration's MedWatch post-licensure database for voluntary reporting of adverse events, of new or worsening CHF in 47 of approximately 300,000 patients worldwide treated with infliximab or etanercept (of whom 38 (81%) had no prior history of CHF, and 10 of whom were less than 50 years of age) have led some to conclude that TNF inhibition may exert a detrimental, rather than protective, effect on the myocardium of RA patients. To date, the only available evidence to refute this supposition comes from Wolfe et al. [27], in which a statistically significant lower rate of self-reported, physician-diagnosed CHF was determined in RA patients receiving treatment with a TNF inhibitor compared to those not treated with TNF inhibitors, even after adjustment for unbalanced clinical characteristics and previous history of CVD (2.8% versus 3.9%, respectively, P = 0.03). A lower rate of incident CHF in TNF inhibitor treated versus untreated patients was also demonstrated (3.5% versus 4.3%, respectively) when the analysis was limited only to data collected after the Food and Drug Administration warning following the RENNAISANCE, RECOVER, and ATTACH trials, although this difference was not statistically significant. No cases of incident CHF in TNF inhibitor treated RA patients who were less than 50 years of age were found, although three cases of incident CHF were reported in RA patients under 50 years of age who were not treated with TNF inhibitors. As noted above, the diagnosis of CHF in this study was not based on predefined clinical and/or imaging criteria nor was the etiology of CHF (ischemic versus non-ischemic versus other) determined; nonetheless, this study provides tantalizing circumstantial support for the notion that TNF-α contributes to the etiology of CHF in RA. Additional indirect support derives from a recent report [125] in which the prescription of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs; including TNF inhibitors) was associated with a 30% reduction in hospitalizations for new-onset CHF from a large administrative claims database of RA patients. Considering only TNF inhibitor treated patients, a 50% reduction in CHF hospitalizations was observed.

To date, few human investigations into the direct effects of TNF-α or TNF inhibitors on the myocardium have been undertaken. Imaging substudies of non-RA patients with advanced CHF showed no effect of etanercept on LVEF (assessed in 215 subjects who underwent radionuclide ventriculography at baseline and at 24 weeks) in RENNAISANCE [126] and a modest increase in LVEF (measured by radionuclide ventriculography) despite clinical worsening in infliximab treated patients in ATTACH [122]. Although studies incorporating direct visualization of myocardial function have yet to be performed in RA patients, clues from animal models of CHF induced by chronic cytokine excess (a setting that may mimic the RA disease state) may serve to explain the apparent contradictions in treatment effects of cytokine inhibition on the myocardium.

Animal models of cytokine induced congestive heart failure

In vitro and animal studies strongly support a mechanistic role for macrophage-derived cytokines, especially TNF-α, in the pathogenesis of CHF, rather than a mere epiphenomenon. Key features of the CHF phenotype, including pulmonary edema, negative inotropy, ventricular dilatation and hypertrophy, endothelial dysfunction, reduced myocardial β-adrenergic responsiveness, and myocyte apoptosis are recapitulated by experimental augmentation of TNF-α [127–129]. In a rat model, continuous infusion of TNF-α via an implanted osmotic infusion pump to levels congruent with those found in human CHF, led to a time-dependent reduction in LVEF and development of left ventricular dilatation [130]. These effects were reversed, at least in part, by removal of the infusion pump or administration of a dimeric TNF receptor antagonist [130].

Transgenic murine models of cardiac-restricted overexpression of TNF-α have been generated by coupling the murine TNF-α gene to the murine α-myosin heavy chain promoter [131–133]. When expression is extremely robust, the animals die quickly (mean 11 days) of a dilated cardiomyopathy that, on histologic examination, is due to a diffuse inflammatory myocarditis [131]. With less robust expression of TNF-α, survival is longer (mean time to death approximately 10 months) and the CHF phenotype evolves more gradually, characterized by ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation, interstitial infiltrates and fibrosis, and depressed adrenergic response. These effects were attenuated or blocked by antagonism of TNF-α [134–136].

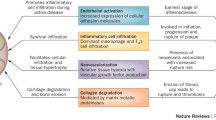

These studies strongly support a central role for TNF-α in mediating the processes leading to myocardial dysfunction. An inflammatory myocarditis has also been described in autopsy studies of RA patients (discussed above). It is tempting to speculate that chronic production of cytokines, including TNF-α, may affect the myocardium in RA in either an endocrine (originating in the synovium) or paracrine (produced in the local environment of the progressively failing myocardium) fashion, contributing to subclinical and eventually clinically recognizable ventricular dysfunction (Fig. 1).

Inflammatory pathways and myocardial remodeling

The process by which cardiac structure and function adapts to physiologic changes is termed 'myocardial remodeling' and involves the cellular and interstitial changes leading to myocyte hypertrophy, ventricular dilatation, alterations in interstitial collagen superstructure, and interstitial myocardial fibrosis [137]. This process is mediated primarily through local expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9, and modulated by expression of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [138]. Circulating levels of MMPs are elevated in patients with overt CHF, regardless of etiology [139–141], suggesting a common unifying mechanism. Overexpression of MMPs and/or reduced expression of TIMPs are associated with proteolysis of the myocardial extracellular fibrillar collagen matrix and progressive ventricular dilatation [142, 143]. Selective and non-selective MMP inhibition reverses or blocks the development of the phenotype [144, 145].

TNF-α has been shown to be a key regulator of MMP expression in myocardial remodeling [135, 146]. In transgenic mice with cardiac restricted overexpression of TNF-α [146], early exposure to elevated TNF-α was associated with an increase in the myocardial zymographic MMP activity/myocardial TIMP (MMP/TIMP) ratio favoring degradation of interstitial fibrillar collagen and development of ventricular dilation and CHF. With aging, however, a shift to increased myocardial TIMP levels and an overall reduction in the MMP/TIMP ratio, an increase in collagen production, and subsequent fibrosis of the dilated ventricle was observed. This later phase was associated with an increase in transforming growth factor-β expression [146]. This time-dependent effect of TNF-α induced myocardial remodeling suggests that there may be a window of opportunity early in disease during which events leading to myocardial interstitial fibrosis may be prevented [147]. Importantly, it is this shift from myocardial interstitial degradation to fibrosis that appears to play a key role in the transition from compensated to decompensated CHF [148]. Moreover, this is supported by the finding that delayed anti-TNF-α therapy, administered at six weeks of age, was able to reverse ventricular dilatation, but not established fibrosis, in a transgenic mouse model of cardiac TNF-α overexpression [149]. The possibility that enhancing TNF-α expression in late CHF might even be desirable in order to reestablish a favorable MMP/TIMP balance has not been explored.

Recent work suggests that cardiac structural homeostasis is regulated in part through a balance between membrane-bound and cleaved TNF-α. Normally, membrane bound TNF-α is converted to its soluble form by cleavage with TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) [150]. In a line of transgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of TNF-α that is resistant to cleavage by TACE, concentric hypertrophy without chamber dilatation was observed [151, 152], whereas mice with overexpression of TNF-α and an intact TACE cleavage site exhibited extracellular matrix degradation and ventricular dilatation [151, 152]. In humans, increased TACE expression parallels the increase in TNF-α expression associated with dilated cardiomyopathy [153] and myocarditis [154]. Little is currently known, however, about the relative amounts or contribution of membrane bound TNF-α to myocardial homeostasis in humans.

In summary, animal studies have shown that the processes leading to cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, interstitial fibrillar collagen degradation, mural realignment, and ultimately to dilated cardiomyopathy are induced and/or regulated, at least in part, by TNF-α. The effects of TNF-α on the myocardium are complex, however, with a pathogenic effect early on and a putative protective effect later in disease. This dichotomy has important potential implications for human disease and has preliminary support from available clinical studies of TNF inhibitors in humans, in which patients with advanced CHF have shown no benefit or worsened when treated with anti-TNF-α therapy. In contrast, in patients with RA and no overt CHF, treatment of RA with TNF inhibitors might offer some protection against cytokine induced CHF.

Conclusion

The evolution of subclinical myocardial dysfunction to overt CHF is associated with significant morbidity and alarming mortality. Population- and clinic-based epidemiologic studies have suggested that RA patients may be more prone to the development of CHF and more susceptible to CHF-related mortality. While some traditional risk factors for CHF are over-represented in RA patients, they do not appear to account for all of the increased CHF risk observed. Other RA associated factors, particularly the chronic elaboration of inflammatory cytokines, are likely substantial contributors to myocardial dysfunction in RA patients. Additional investigation is needed to clarify both the direct effects of the RA disease process and the effects of RA-directed therapeutics on the myocardium at all stages of disease in order to define appropriate strategies to prevent or attenuate the development of CHF in RA patients.

Abbreviations

- ATTACH:

-

Anti-TNF-α Therapy Against Chronic Heart failure

- CHF:

-

congestive heart failure

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- IL:

-

interleukin

- LV:

-

left ventricular

- LVEF:

-

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- MMP:

-

matrix metalloproteinase

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RECOVER = Research into Etanercept:

-

Cytokine Antagonism in Ventricular Dysfunction Trial

- RENNAISANCE:

-

Randomized Etanercept North American Strategy to Study Antagonism of Cytokines

- RF:

-

rheumatoid factor

- TACE:

-

TNF-α converting enzyme

- TIMP:

-

tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-α.

References

Asanuma Y, Oeser A, Shintani AK, Turner E, Olsen N, Fazio S, Linton MF, Raggi P, Stein CM: Premature coronary-artery atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349: 2407-2415.

Roman MJ, Shanker BA, Davis A, Lockshin MD, Sammaritano L, Simantov R, Crow MK, Schwartz JE, Paget SA, Devereux RB, Salmon JE: Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349: 2399-2406.

del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A: High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 2737-2745.

Wallberg-Jonsson S, Johansson H, Ohman ML, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S: Extent of inflammation predicts cardiovascular disease and overall mortality in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. A retrospective cohort study from disease onset. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2562-2571.

Wolfe F, Freundlich B, Straus WL: Increase in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease prevalence in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 36-40.

de Lemos JA, Hennekens CH, Ridker PM: Plasma concentration of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and subsequent cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 36: 423-426.

Wallberg-Jonsson S, Cederfelt M, Rantapaa DS: Hemostatic factors and cardiovascular disease in active rheumatoid arthritis: an 8 year followup study. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 71-75.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH: Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000, 101: 1767-1772.

Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F: Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002, 359: 1173-1177.

Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, Cinquegrani MP, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Goldstein S, Gregoratos G, Jessup , et al: ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 38: 2101-2113.

Massie BM, Shah NB: Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management. Am Heart J. 1997, 133: 703-712.

Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA: Prevalence and mortality-rate of congestive-heart-failure in the United-States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992, 20: 301-306.

Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Rashidee A: Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1985 to 1995. Am Heart J. 1999, 137: 352-360.

Alexander M, Grumbach K, Remy L, Rowell R, Massie BM: Congestive heart failure hospitalizations and survival in California: Patterns according to race ethnicity. Am Heart J. 1999, 137: 919-927.

Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Kupka MJ, Ho KK, Murabito JM, Vasan RS: Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 1397-1402.

Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ: Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. J Am Med Assoc. 2004, 292: 344-350.

Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MCJM, Straus SMJM, Hofman A, Deckers JW, Witteman JC, Stricker BH: Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure: The Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25: 1614-1619.

Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR, Redfield MM: Congestive heart failure in the community: trends in incidence and survival in a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 1999, 159: 29-34.

Ho KKL, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D: The epidemiology of heart-failure: the Framingham-study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993, 22: A6-A13.

Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR, Redfield MM: Congestive heart failure in the community: a study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation. 1998, 98: 2282-2289.

Mckee PA, Castelli WP, Mcnamara PM, Kannel WB: Natural history of congestive heart failure: Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971, 285: 1441-1446.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D: Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2002, 106: 3068-3072.

O'Connell JB: The economic burden of heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2000, 23: 6-10.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM: Comorbidity in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2475-2479.

Kremers H, Nicola P, Crowson C, Ballman K, Gabriel SE: Risk of heart failure among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: S706-

Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE: The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 412-420.

Wolfe F, Michaud K: Heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: Rates, predictors, and the effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Am J Med. 2004, 116: 305-311.

Mutru O, Laakso M, Isomaki H, Koota K: Cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid-arthritis. Cardiology. 1989, 76: 71-77.

Nicola P, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, Gabriel SE: Is congestive heart failure the major contributor of the increased mortality in rheumatoid arthritis?. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: S674-

Remes J, Miettinen H, Reunanen A, Pyorala K: Validity of clinical-diagnosis of heart-failure in primary health-care. Eur Heart J. 1991, 12: 315-321.

Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, Ho KKL: The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. J Am Med Assoc. 1996, 275: 1557-1562.

Cathcart ES, Spodick DH: Rheumatoid heart disease. A study of the incidence and nature of cardiac lesions in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med. 1962, 266: 959-964.

Turner LW, Lansbury J: Low diastolic pressure as a clinical feature of rheumatoid arthritis and its possible etiologic significance. Am J Med Sci. 1954, 227: 503-508.

Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, Cannuscio CC, Mandl LA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC: Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003, 107: 1303-1307.

McEntegart A, Capell HA, Creran D, Rumley A, Woodward M, Lowe GD: Cardiovascular risk factors, including thrombotic variables, in a population with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001, 40: 640-644.

Pope JE, Anderson JJ, Felson DT: A metaanalysis of the effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on blood-pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1993, 153: 477-484.

Kannel WB, Abbott RD: Incidence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction. An update on the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1984, 311: 1144-1147.

Elhendy A, Schinkel AFL, van Domburg RT, Bax JJ, Poldermans D: Incidence and predictors of heart failure during long-term follow-up after stress Tc-99m sestamibi tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004, 11: 527-533.

Park YB, Ahn CW, Choi HK, Lee SH, In BH, Lee HC, Nam CM, Lee SK: Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: morphologic evidence obtained by carotid ultrasound. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 1714-1719.

Gottdiener JS, Arnold AM, Aurigemma GP, Polak JF, Tracy RP, Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Rutledge JE, Boineau RC: Predictors of congestive heart failure in the elderly: the cardiovascular health study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 35: 1628-1637.

He J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, Vupputuri S, Loria C, Whelton PK: Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2001, 161: 996-1002.

Hakala M, Ilonen J, Reijonen H, Knip M, Koivisto O, Isomaki H: No association between rheumatoid arthritis and insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: An epidemiologic and immunogenetic study. J Rheumatol. 1992, 19: 856-858.

Arnlov J, Lind L, Zethelius B, Andren B, Hales CN, Vessby B, Lithell H: Several factors associated with the insulin resistance syndrome are predictors of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in a male population after 20 years of follow-up. Am Heart J. 2001, 142: 720-724.

Dessein P, Stanwix A, Joffe B: Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis versus osteoarthritis: Acute phase response related decreased insulin sensitivity and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as clustering of metabolic syndrome features in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002, 4: R5-

Svenson KLG, Pollare T, Lithell H, Hallgren R: Impaired glucose handling in active rheumatoid-arthritis: Relationship to peripheral insulin resistance. Metabolism. 1988, 37: 125-130.

Lebowitz WB: Heart in rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid disease): a clinical and pathologicalstudy of 62 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1963, 58: 102-

Guedes C, Bianchi-Fior P, Cormier B, Barthelemy B, Rat AC, Boissier MC: Cardiac manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: A case-control transesophageal echocardiography study in 30 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 45: 129-135.

Iveson JM, Thadani U, Ionescu M, Wright V: Aortic valve incompetence and replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1975, 34: 312-320.

Chand EM, Freant LJ, Rubin JW: Aortic valve rheumatoid nodules producing clinical aortic regurgitation and a review of the literature. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1999, 8: 333-338.

Boxt LM: MR imaging of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 1996, 4: 307-325.

Zitnik RJ, Cooper JAD: Pulmonary-disease due to anti-rheumatic agents. Clin Chest Med. 1990, 11: 139-150.

Turesson C, Jacobsson LTH: Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004, 33: 65-72.

Radoux V, Menard HA, Begin R, Decary F, Koopman WJ: Airways disease in rheumatoid-arthritis patients: one element of a general exocrine dysfunction. Arthritis Rheum. 1987, 30: 249-256.

Zrour SH, Touzi M, Bejia I, Golli M, Rouatbi N, Sakly N, Younes M, Tabka Z, Bergaoui N: Correlations between high-resolution computed tomography of the chest and clinical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Prospective study in 75 patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2005, 72: 41-47.

Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Testa A, Garcia-Castelo A, Garcia-Porrua C, Llorca J, Ollier WER, Gonzalez-Gay MA: Echocardiographic and Doppler findings in long-term treated rheumatoid arthritis patients without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 33: 231-238.

Dawson JK, Goodson NG, Graham DR, Lynch MP: Raised pulmonary artery pressures measured with Doppler echocardiography in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2000, 39: 1320-1325.

Keser G, Capar I, Aksu K, Inal V, Danaoglu Z, Savas R, Oksel F, Tunc E, Kabasakal Y, Kitapcioglu G, Doganavsargil E: Pulmonary hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004, 33: 244-245.

Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Javier NF, O'Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE, Samet JM: Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease. Cross-sectional results of the sleep heart health study. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2001, 163: 19-25.

Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J: Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 1378-1384.

Chaouat A, Weitzenblum E, Krieger J, Oswald M, Kessler R: Pulmonary hemodynamics in the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: Results in 220 consecutive patients. Chest. 1996, 109: 380-386.

Hayashi M, Fujimoto K, Urushibata K, Uchikawa Si, Imamura H, Kubo K: Nocturnal oxygen desaturation correlates with the severity of coronary atherosclerosis in coronary artery disease. Chest. 2003, 124: 936-941.

Minoguchi K, Tazaki T, Yokoe T, Minoguchi H, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M, Adachi M: Elevated production of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} by monocytes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2004, 126: 1473-1479.

Redlund-Johnell I: Upper airway obstruction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and temporomandibular joint destruction. Scand J Rheumatol. 1988, 17: 273-279.

Zamarron C, Maceiras F, Mera A, Gomez-Reino JJ: Effect of the first infliximab infusion on sleep and alertness in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 88-90.

Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Lin HM, Bixler EO, Trakada G, Chrousos GP: Marked decrease in sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea by etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} antagonist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 4409-4413.

Symmons DP, Bankhead CR, Harrison BJ, Brennan P, Barrett EM, Scott DG, Silman AJ: Blood transfusion, smoking, and obesity as risk factors for the development of rheumatoid arthritis: Results from a primary care-based incident case-control study in Norfolk, England. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 1955-1961.

Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PWF, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS: Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 305-313.

Zhou YT, Grayburn P, Karim A, Shimabukuro M, Higa M, Baetens D, Orci L, Unger RH: Lipotoxic heart disease in obese rats: Implications for human obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 1784-1789.

Gvozdjakova A, Kucharska J, Gvozdjak J: Effect of smoking on the oxidative processes of cardiomyocytes. Cardiology. 1992, 81: 81-84.

Roubenoff R, Roubenoff RA, Cannon JG, Kehayias JJ, Zhuang H, Dawson-Hughes B, Dinarello CA, Rosenberg IH: Rheumatoid cachexia: Cytokine-driven hypermetabolism accompanying reduced body cell mass in chronic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1994, 93: 2379-2386.

Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, Hruban RH, Clemetson DE, Howard DL, Baughman KL, Kasper EK: Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 1077-1084.

Sokoloff L: Cardiac involvement in rheumatoid arthritis and allied disorders: Current concepts. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1964, 32: 847-850.

Abbas A, Byrd BF: Right-sided heart failure due to right ventricular cavity obliteration by rheumatoid nodules. Am J Cardiol. 2000, 86: 711-712.

Ojeda VJ, Stuckey BGA, Owen ET, Walters MNI: Cardiac rheumatoid nodules. Med J Australia. 1986, 144: 92-93.

Peter H, Bernd S, Thomas G, Jurgen S, Ulf M: Fatal outcome of constrictive pericarditis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2003, 23: 312-314.

Yurchak PM, Deshpande V: Case 2–2003: A 60-year-old man with mild congestive heart failure of uncertain cause. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348: 243-249.

Slack JD, Waller B: Acute congestive-heart-failure due to the arteritis of rheumatoid-arthritis: Early diagnosis by endomyocardial biopsy – a case-report. Angiology. 1986, 37: 477-482.

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Levy D: Left ventricular dilatation and the risk of congestive heart failure in people without myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997, 336: 1350-1355.

Drazner MH, Rame JE, Marino EK, Gottdiener JS, Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Manolio TA, Dries DL, Siscovick DS: Increased left ventricular mass is a risk factor for the development of a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction within five years: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 43: 2207-2215.

Lauer MS, Evans JC, Levy D: Prognostic implications of subclinical left-ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in men free of overt cardiovascular-disease (the Framingham heart-study). Am J Cardiol. 1992, 70: 1180-1184.

The SOLVD Investigators: Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325: 293-302.

Wang TJ, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS: The epidemiology of "asymptomatic" left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Implications for screening. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 138: 907-916.

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D: Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: Prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999, 33: 1948-1955.

Zile MR, Brutsaert DL: New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part I: diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation. 2002, 105: 1387-1393.

Aurigemma GP, Gottdiener JS, Shemanski L, Gardin J, Kitzman D: Predictive value of systolic and diastolic function for incident congestive heart failure in the elderly: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 37: 1042-1048.

Mustonen J, Laakso M, Hirvonen T, Mutru O, Pirnes M, Vainio P, Kuikka JT, Rautio P, Lansimies E: Abnormalities in left-ventricular diastolic function in male-patients with rheumatoid-arthritis without clinically evident cardiovascular-disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993, 23: 246-253.

Cindas A, Gokce-Kutsal Y, Tokgozoglu L, Karanfil A: QT dispersion and cardiac involvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002, 31: 22-26.

Corrao S, Salli L, Arnone S, Scaglione R, Pinto A, Licata G: Echo-Doppler left ventricular filling abnormalities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996, 26: 293-297.

Wislowska M, Sypula S, Kowalik I: Echocardiographic findings, 24-hour electrocardiographic Holter monitoring in patients with rheumatoid arthritis according to Steinbrocker's criteria, functional index, value of Waaler-Rose titre and duration of disease. Clin Rheumatol. 1998, 17: 369-377.

Montecucco C, Gobbi G, Perlini S, Rossi S, Grandi AM, Caporali R, Finardi G: Impaired diastolic function in active rheumatoid arthritis. Relationship with disease duration. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999, 17: 407-412.

Wislowska M, Sypula S, Kowalik I: Echocardiographic findings and 24-h electrocardiographic Holter monitoring in patients with nodular and non-nodular rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1999, 18: 163-169.

Di Franco M, Paradiso M, Mammarella A, Paoletti V, Labbadia G, Coppotelli L, Taccari E, Musca A: Diastolic function abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Evaluation by echo Doppler transmitral flow and pulmonary venous flow: relation with duration of disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000, 59: 227-229.

Alpaslan M, Onrat E, Evcik D: Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of ventricular function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2003, 22: 84-88.

Levendoglu F, Temizhan A, Ugurlu H, Ozdemir A, Yazici M: Ventricular function abnormalities in active rheumatoid arthritis: a Doppler echocardiographic study. Rheumatol Int. 2004, 24: 141-146.

Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH: Diastolic heart failure: Abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350: 1953-1959.

Petrie MC, Hogg K, Caruana L, McMurray JJV: Poor concordance of commonly used echocardiographic measures of left ventricular diastolic function in patients with suspected heart failure but preserved systolic function: Is there a reliable echocardiographic measure of diastolic dysfunction?. Heart. 2004, 90: 511-517.

Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Leip EP, Wang TJ, Wilson PWF, Levy D: Plasma natriuretic peptides for community screening for left ventricular hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction: The Framingham heart study. J Am Med Assoc. 2002, 288: 1252-1259.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Omland T, Wolf PA, Vasan RS: Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350: 655-663.

Yasuda M, Yasuda D, Tomooka K, Nobunaga M: Plasma concentration of human atrial natriuretic hormone in patients with connective-tissue diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 1993, 12: 231-235.

Shichiri M, Miyasaka N, Hirata Y, Ando K, Marumo F: Appearance of beta-human atrial-natriuretic-peptide in collagen disease. J Endocrinol. 1991, 130: 159-161.

Vasan RS, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Wilson PW: Plasma homocysteine and risk for congestive heart failure in adults without prior myocardial infarction. J Am Med Assoc. 2003, 289: 1251-1257.

Sundstrom J, Sullivan L, Selhub J, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Levy D, Wilson PW, Vasan RS: Relations of plasma homocysteine to left ventricular structure and function: The Framingham heart study. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25: 523-530.

Welch GN, Loscalzo J: Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1998, 338: 1042-1050.

Wallberg-Jonsson S, Cvetkovic JT, Sundqvist KG, Lefvert AK, Rantapaa-Dahlqvst S: Activation of the immune system and inflammatory activity in relation to markers of atherothrombotic disease and atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29: 875-882.

Yxfeldt A, Wallberg-Jonsson S, Hultdin J, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S: Homocysteine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in relation to inflammation and B-vitamin treatment. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003, 32: 205-210.

Prodanowich S, Ma F, Taylor JR, Pezon C, Fasihi T, Kirsner RS: Methotrexate reduces incidence of vascular diseases in veterans with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005, 52: 262-267.

Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL: Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: An analysis of the cytokine database from the vesnarinone trial (VEST). Circulation. 2001, 103: 2055-2059.

Kubota T, Miyagishima M, Alvarez RJ, Kormos R, Rosenblum WD, Demetris AJ, Semigran MJ, Dec GW, Holubkov R, McTiernan CF, et al: Expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the failing human heart: Comparison of recent-onset and end-stage congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000, 19: 819-824.

Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, Fillit HM, Packer M: Elevated circulating levels of tumor-necrosis-factor in severe chronic heart-failure. N Engl J Med. 1990, 323: 236-241.

Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Francis DP, Kemp M, Nicbauer J, Volk HD, Coats AJS, Anker SD: Cytokine parameters predict increased mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2000, 21: 233-

Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL: Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: A report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996, 27: 1201-1206.

Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Lee J, Durand JB, Bies RD, Young JB, Mann DL: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and tumor necrosis factor receptors in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1996, 93: 704-711.

Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, Sawyer DB, Levy D, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB: Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2003, 107: 1486-1491.

Cesari M, Penninx BWJH, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Rubin SM, Ding J, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Pahor M: Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events: Results from the Health ABC study. Circulation. 2003, 108: 2317-2322.

Birks EJ, Latif N, Owen V, Bowles C, Felkin LE, Mullen AJ, Khaghani A, Barton PJ, Polak JM, Pepper JR: Quantitative myocardial cytokine expression and activation of the apoptotic pathway in patients who require left ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 2001, 104: 233-240.

Birks EJ, Burton PBJ, Owen V, Mullen AJ, Hunt D, Banner NR, Barton PJ, Yacoub MH: Elevated tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} and interleukin-6 in myocardium and serum of malfunctioning donor hearts. Circulation. 2000, 102: 352-358.

Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Wasko MC, Moreland LW, Weaver AL, et al: A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 1586-1593.

Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Weisman M, Emery P, Feldmann M, et al: Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 1594-1602.

Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, Bulpitt KJ, Fleischmann RM, Fox RI, Jackson CG, Lange M, Burge DJ: A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 253-259.

Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Moreland LW, Weisman MH, Birbara CA, Teoh LA, Fischkoff SA, Chartash EK: Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha mono-clonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: The ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 35-45.

Foley RN, Murray AM, Li S, Herzog CA, McBean AM, Eggers PW, Collins AJ: Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population, 1998 to 1999. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005, 16: 489-495.

Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, Fasanmade AA, Willerson JT: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of Inflix-imab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-α, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: Results of the Anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart failure (ATTACH) Trial. Circulation. 2003, 107: 3133-3140.

Mann DL, McMurray JJV, Packer M, Swedberg K, Borer JS, Colucci WS, Djian J, Drexler H, Feldman A, Kober L, et al: Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: Results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL). Circulation. 2004, 109: 1594-1602.

Khanna D, McMahon M, Furst DE: Anti-tumor necrosis factor a therapy and heart failure: What have we learned and where do we go from here?. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 1040-1050.

Bernatsky S, Hudson M, Suissa S: Anti-rheumatic drug use and risk of hospitalization for congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005, 44: 677-680.

Hochreiter CA, Carter J, Herrold EMM, Warren MS, Whitmore J, Borer JS: Treatment with Etanercept (Enbrel) does not affect left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in patients with chronic heart failure. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: s120-

Chung MK, Gulick TS, Rotondo RE, Schreiner GF, Lange LG: Mechanism of cytokine inhibition of beta-adrenergic agonist stimulation of cyclic AMP in rat cardiac myocytes. Impairment of signal transduction. Circ Res. 1990, 67: 753-763.

Krown KA, Page MT, Nguyen C, Zechner D, Gutierrez V, Comstock K, Glembotski CC, Quintana PJ, Sabbadini RA: Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes.Involvement of the sphingolipid signaling cascade in cardiac cell death. J Clin Invest. 1996, 98: 2854-2865.

Suffredini AF, Fromm RE, Parker MM, Brenner M, Kovacs JA, Wesley RA, Parrillo JE: The cardiovascular response of normal humans to the administration of endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321: 280-287.

Bozkurt B, Kribbs SB, Clubb FJ, Michael LH, Didenko VV, Hornsby PJ, Seta Y, Oral H, Spinale FG, Mann DL: Pathophysiologically relevant concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha promote progressive left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling in rats. Circulation. 1998, 97: 1382-1391.

Kubota T, McTiernan CF, Frye CS, Demetris AJ, Feldman AM: Cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha causes lethal myocarditis in transgenic mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 29: 29165-

Bryant D, Becker L, Richardson J, Shelton J, Franco F, Peshock R, Thompson M, Giroir B: Cardiac failure in transgenic mice with myocardial expression of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}. Circulation. 1998, 97: 1375-1381.

Li X, Moody MR, Engel D, Walker S, Clubb FJ, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL, Reid MB: Cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} causes oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in mouse diaphragm. Circulation. 2000, 102: 1690-1696.

Kadokami T, Frye C, Lemster B, Wagner CL, Feldman AM, McTiernan CF: Anti-tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} antibody limits heart failure in a transgenic model. Circulation. 2001, 104: 1094-1097.

Li YY, Feng YQ, Kadokami T, McTiernan CF, Draviam R, Watkins SC, Feldman AM: Myocardial extracellular matrix remodeling in transgenic mice overexpressing tumor necrosis factor alpha can be modulated by anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 12746-12751.

Sivasubramanian N, Coker ML, Kurrelmeyer KM, MacLellan WR, Demayo FJ, Spinale FG, Mann DL: Left ventricular remodeling in transgenic mice with cardiac restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Circulation. 2001, 104: 826-831.

Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N: Cardiac remodeling – concepts and clinical implications: A consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 35: 569-582.

Wilson EM, Gunasinghe HR, Coker ML, Sprunger P, Lee-Jackson D, Bozkurt B, Deswal A, Mann DL, Spinale FG: Plasma matrix metalloproteinase and inhibitor profiles in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2002, 8: 390-398.

Coker ML, Jolly JR, Joffs C, Etoh T, Holder JR, Bond BR, Spinale FG: Matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity in isolated myocytes after neurohormonal stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001, 281: H543-H551.

Coker ML, Thomas CV, Clair MJ, Hendrick JW, Krombach RS, Galis ZS, Spinale FG: Myocardial matrix metalloproteinase activity and abundance with congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1998, 274: H1516-H1523.

Altieri P, Brunelli C, Garibaldi S, Nicolino A, Ubaldi S, Spallarossa P, Olivotti L, Rossettin P, Barsotti A, Ghigliotti G: Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 are increased in plasma of patients with heart failure. EurJ Clin Invest. 2003, 33: 648-656.

Gao CQ, Sawicki G, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Csont T, Wozniak M, Ferdinandy M, Schulz R: Matrix metalloproteinase-2 mediates cytokine-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2003, 57: 426-433.

Roten L, Nemoto S, Simsic J, Coker ML, Rao V, Baicu S, Defreyte G, Soloway PJ, Zile MR, Spinale FG: Effects of gene deletion of the tissue inhibitor of the matrix metalloproteinase-type 1 (TIMP-1) on left ventricular geometry and function in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000, 32: 109-120.

Peterson JT, Hallak H, Johnson L, Li H, O'Brien PM, Sliskovic DR, Bocan TM, Coker ML, Etoh T, Spinale FG: Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in a rat model of progressive heart failure. Circulation. 2001, 103: 2303-2309.

Li YY, Kadokami T, Wang P, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM: MMP inhibition modulates TNF-alpha transgenic mouse phenotype early in the development of heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002, 282: H983-H989.

Sivasubramanian N, Coker ML, Kurrelmeyer KM, MacLellan WR, Demayo FJ, Spinale FG, Mann DL: Left ventricular remodeling in transgenic mice with cardiac restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Circulation. 2001, 104: 826-831.

Berry MF, Woo YJ, Pirolli TJ, Bish LT, Moise MA, Burdick JW, Morine KJ, Jayasankar V, Gardner TJ, Sweeney HL: Administration of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor at the time of myocardial infarction attenuates subsequent ventricular remodeling. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004, 23: 1061-1068.

Hein S, Arnon E, Kostin S, Schonburg M, Elsasser A, Polyakova V, Bauer EP, Klovekorn WP, Schaper J: Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart: Structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation. 2003, 107: 984-991.

Kubota T, Bounoutas GS, Miyagishima M, Kadokami T, Sanders VJ, Bruton C, Robbins PD, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM: Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor abrogates myocardial inflammation but not hypertrophy in cytokine-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000, 101: 2518-2525.

Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, et al: A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997, 385: 729-733.

Diwan A, Dibbs Z, Nemoto S, DeFreitas G, Carabello BA, Sivasubramanian N, Wilson EM, Spinale FG, Mann DL: Targeted overexpression of noncleavable and secreted forms of tumor necrosis factor provokes disparate cardiac phenotypes. Circulation. 2003, 109: 262-268.

Dibbs ZI, Diwan A, Nemoto S, DeFreitas G, Abdellatif M, Carabello BA, Spinale FG, Feuerstein G, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL: Targeted overexpression of transmembrane tumor necrosis factor provokes a concentric cardiac hypertrophic phenotype. Circulation. 2003, 108: 1002-1008.

Satoh M, Nakamura M, Saitoh H, Satoh H, Maesawa C, Segawa I, Tashiro A, Hiramori K: Tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} converting enzyme and tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1999, 99: 3260-3265.

Satoh M, Nakamura M, Satoh H, Saitoh H, Segawa I, Hiramori K: Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 36: 1288-1294.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an American College of Rheumatology Clinical Investigator Fellowship Award (JTG), an Arthritis National Research Foundation Award (JTG), and by Grant AR050026-01 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (JMB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr Giles receives grant support from the American College of Rheumatology and the Arthritis National Research Foundation. Dr Bathon receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, Amgen, IDEC/Genentech. Dr Bathon is a consultant to Abbott.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giles, J.T., Fernandes, V., Lima, J.A. et al. Myocardial dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Arthritis Res Ther 7, 195 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1814

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1814