Abstract

Australia has two species of Artemia: A. franciscana introduced to salt works and apparently not spreading, and parthenogenetic Artemia presently spreading widely through southwestern Australia. In addition, and unique to Australia, there are 18 described species of Parartemia in hypersaline lakes. All Parartemia use a lock and key mechanism in amplexus and hence have distinctive antennal-head features in males and thoracic modifications in females. Various factors, including climatic fluctuations and isolation, contribute to a far higher diversity in the southwest of the continent. There are few congeneric occurrences of Parartemia possibly due to their consuming largely uniform allochthonous organic matter rather than multisized planktonic algae. In P. zietziana there are 2–3 cohorts a year each persisting 3–9 months. Up to 80% of assimilation is used in respiration and at times energy balance is negative, which accounts for its continuous mortality, inconsistent growth rates and unpredictable recruitment. Many species are as osmotically competent as Artemia, but are at a disadvantage in hypersaline waters >250 g L-1 as they lack the haemoglobin of Artemia. Parartemia acidiphila and P. contracta live in markedly acid waters to pH 3.5, where dissolved carbonate and bicarbonate are unavailable, and hence they must have evolved an additional proton pump to produce ATP from endogenous CO2. Occurrences of some species have been severely curtailed by lake salinisation (which includes acidification and changes in hydroperiod), so that their continued existence is in doubt. A few species of the otherwise freshwater Branchinella occur in mainly hyposaline waters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Truly halophilic anostracans occur in two monogeneric families in the Artemiina, a major subdivision of the Anostraca. The Artemiidae contains Artemia, with six bisexual species and several parthenogenetic strains worldwide [1], whereas the Parartemiidae encompasses Parartemia, an Australian endemic genus of 18 described species [2]. Australia has a plethora of anostracan species living in inland saline waters, more than any other continent, and besides these, there are many Branchinella, mainly in hyposaline waters [3]. Naturally occurring Artemia exist in a few isolated lakes in coastal Western Australia near Perth [4], which may represent a parthenogenetic strain of one of the widespread Eurasian species [5]. In addition, the New World Artemia franciscana Kellogg, 1906 has been introduced to Qld, SA and WA. These Australian halophilic species largely fill the niche of Artemia and Phallocryptus on other continents.

Realisation of the diversity of halophilic Anostraca is only recent, with most of the ecology of Parartemia being researched in Victoria on P. zietziana in the 1970s and most of taxonomy in the 1940s and since 2000. There has been no integrated account of Artemia and Parartemia in Australia since Williams & Geddes [6] and the situation now is quite different, especially with improved knowledge of Branchinella’s foray into saline waters and of conservation issues. It is the purpose of this review to bring the scattered published and grey literature together to provide an integrated ecology of brine shrimps in Australia. It will also reveal some major knowledge gaps.

Review

Artemia in Australia

Over a century ago, three endemic species of Artemia were described from Australian waters. These were A. proxima King, 1855, A. westraliensis Sayce, 1903 (nomina nuda, see [2]) and A. australis Sayce, 1903 (nomen dubium, see [2]). The descriptions are inadequate and no material exists for A. proxima, which is surmised to be Artemia, but introduced on salt making equipment. The other two are a few distorted females in museums: the first is a Branchinella female, most of which are indistinguishable from one another, and the second is a Parartemia [7, 8].

Artemia franciscana has been introduced to a number of salt works such as at Bowen and Port Alma in Qld, Dry Creek near Adelaide in SA (where it has replaced parthenogenetic Artemia; P. Coleman, pers. comm.), Port Hedland and Karrata in WA (M. Coleman, pers. comm.) (Figure 1). Parthenogenetic Artemia occurs in salt works at Onslow, Lake McLeod, Shark Bay and also in an industrial works at Three Springs, WA, often colonising of their own accord (M. Coleman & B. Datson, pers. comm.) (Figure 1). This species occurs naturally in salt lakes on Rottnest Is off Perth and in some coastal lakes south of Perth [4] but is also presently spreading across the WA Wheatbelt to sites including Coomberdale near Moora, northeast of Wubin, east of Pengilley, and Fitzgerald River (G. Janicke, pers. comm. & author’s unpublished data) into secondarily salinised lakes and river pools where the environment is now more suited to them than to native Parartemia. It also occurs in the remote and highly episodic Lake Boonderoo on the Nullarbor Plain where there are no records of Parartemia ever being present, but this may be due to this lake’s remoteness (J. Lane, pers. comm.) (Figure 1). In 2011, it reached an isolated salt works based in a natural lake near Lake Alexandrina, SA (M. Coleman, pers. comm.). This recent spread of parthenogenetic Artemia is not being monitored, and the public is not being made aware of the problem. The prediction that A. franciscana is likely to spread from salt works [9] has not yet been realised. Certainly it is persisting in places where salt used to be harvested such as near Port Augusta, SA, Hutt Lagoon and Koorkoodine WA, but it is not known to have spread from these either [10].

Most information on Artemia (e.g. [1, 11]) comes from the northern hemisphere, though some studies include comparative data from Australia (e.g. [12–14]). Although the large salt works in northwest Australia monitor Artemia activity (M. Coleman, pers. comm.), there has been no published research. Before 1975, little was known on Artemia and Parartemia in Australia, which Geddes & Williams tried to redress [6, 15–17] with comparisons of Artemia and the local Parartemia, but at the time Artemia was not spreading and the high biodiversity and physiology of Parartemia were unknown.

Parartemia: taxonomy

It was not until 1903 that the first species of Parartemia (as P. zietziana, Sayce) was described [18]; any brine shrimp encountered before this date was thought to be Artemia (see above). In 1910, Daday [19] placed it in its own family, but it then spent more than 90 years in the family Branchipodidae until Weekers et al. [20], using molecular techniques, showed it to be a family in its own right, which vicariates with the Artemiidae and indeed is its sister group.

Presently, 18 described species of Parartemia are known [21–24] with at least one undescribed species [25]. Molecular analyses of most of these support specific delineations based on morphological differences, though P. contracta could represent two species [26], I. Kappas, pers. comm.). The separation of P minuta and P. mouritzi [24] from the remainder was also supported molecularly (I. Kappas, pers. comm). The great majority of Parartemia species occur in southwestern Western Australia: 13 occur in WA, 7 in SA (two of these shared with WA), 2 in Victoria and one each in NT, Queensland and Tasmania [all of latter four occurrences shared with SA or WA (Table 1)]. The high species richness in WA is thought to be associated with the abundance and diversity of saline habitats there and their great age, while contrastingly the low diversity in eastern Australia is in tune with the simplicity of saline environments there [6]. Also promoting diversity in WA is past climate changes [27] and the alleged poor dispersal abilities of Parartemia due to their eggs sinking and being bound to bottom substrates [10, 15]. Detailed distribution maps are available in Timms et al. [10] and Timms [24].

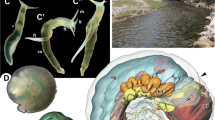

Parartemia males are distinctive in having the basal third of the second antenna fused (Figure 2a), which has a pair of dorsoventrally flattened rectangular or short blade-like distal processes and also a pair of digitiform anterior processes [24]. The distal segment of the antenna is long and slender and only slightly curving medially. Females (Figure 2b) are distinctive with an acute labrum pointing anteriodorsally (and hence easily distinguished from Artemia females) [23]. Most have various adaptations of the pregenital segments of the thorax (segments 8–11 in most, but as forward as segment 5 in P. minuta) in order to be clasped properly by the male antenna of the appropriate species [28]. Most females have brood chambers with lateral lobes though a few species have compact rounded chambers (both structures quite different from other Australian anostracans except Artemia) [24].

All species use a lock and key mechanism in amplexus [28] with the male distal antennomeres locking around the female 11th thoracic segment or thereabouts and the anterior processes touching the female dorsa of thoracic segments 10 and 9 and maybe more depending on whether female segments are shortened by contraction and the length the male anterior processes. The female 11th thoracopod is greatly reduced to facilitate this coupling. Keys to Parartemia species utilize these secondary sex characteristics [24].

In a sense it is a puzzle why Parartemia utilizes lock and key amplexus when congeneric occurrences are rare, so the need for preventing hybridisation is almost nil. However many species often occur in adjacent lakes in WA and SA, and it is possible eggs may perhaps disperse outside their own lake into a nearby lake with a different species. In this case, competitive exclusion would be served by the incumbent species being unable to mate in the first instance without wasting scarce resources (see below) on unfit hybrids.

Parartemia: physiology

Parartemia zietziana is an efficient hypo-osmotic regulator [29] (Figure 3). Like Artemia, it is a respiratory regulator, meaning the respiration rate remains constant over a wide range of oxygen concentrations. For Parartemia, regulation ceases at about 2 mg L-1 of oxygen, whereas for Artemia it stops at about 1 mg L-1 because of their ability to produce haemoglobin [30]. Osmoregulation accounts for only 3% of the total variance in respiratory rate [31].

Osmotic regulation in Parartemia zietziana (redrawn from [ [28] ]).

Parartemia zietziana achieves regulation by sodium excretion via the Na, K-ATPase system [32]. This creates a heavy demand on cellular reserves of ATP, which is satisfied from increased glycogen breakdown with the ATP supplied by a facultative aerobic glycolytic cycle. The CO2 to run the C-4 pathway comes from dissolved carbonate and bicarbonate in alkaline saline waters plus some endogenous CO2 too [33]. This species has the highest known field salinity range, possibly because it has been more intensely studied. Other species known to inhabit hypersaline lakes >200 mg L-1 include P. acidiphila, P. contracta, P. longicaudata, P. minuta, P. purpurea, P. serventyi and P. veronicae (Table 2). Further field data on these and other species will no doubt raise their upper known limits, but probably not for at least P. cylindifera. In the Esperance hinterland and on Eyre Peninsula where series of lakes have been studied [34, 35] this species occurs in lower salinity lakes while others (P. acidiphila, P. longicaudata, P. purpurea, P. zietziana) live at higher salinities. Parartemia extracta may be another example of a species living at moderate salinities, this time in the northern Wheatbelt (A. Pinder, pers. comm.).

In the Dry Creek Saltfield near Adelaide, P. zietziana and parthenogenetic Artemia (recorded as A. salina in the study) co-occur; P. zietziana alone at 112–214 g L-1 and Artemia alone above 285 g L-1 while both in the same ponds between 214 and 285 g L-1 [30]. While P. zietziana can osmoregulate above 285 g L-1, it is at a disadvantage compared to Artemia because it lacks haemoglobin (see above).

Most species of Parartemia live in alkaline waters, but three species, P. acidiphila, P. contracta, P. mouritzi, naturally live in acid waters, where carbonate and bicarbonate are not available. Conte & Geddes [32] showed that P. contracta must have evolved an additional proton pump to produce ATP from endogenous CO2 and perhaps also from dissolved CO2. Presumably, P. acidiphila living as it does in waters down to pH 3.5 [34] is similarly endowed, but P. mouritzi may not be, as so far it has not been found below pH 6.2. Parartemia serventyi, though typically living in alkaline waters, can survive mildly acid conditions of secondary salinised waters (G. Janicke, pers. comm.), so perhaps it has similar physiological modifications. Survival mechanisms in acidified waters would obviously be a productive area for future investigations.

Parartemia: aquaculture

Artemia is cultured worldwide and also in Australia, and in the early 2000s attempts were made to culture Parartemia commercially. Securing eggs was a problem, as they sink and become secure in the bottom substrates, so that the ready collection of floating eggs as in Artemia was impossible. The larger species were tried but unsuccessfully as growth rates were low and erratic (A. Savage, pers. comm.). Perhaps if the smaller species of the remote inland (see below) were tried there may have been some success, but egg collection remains a problem.

Parartemia: ecology

In Victorian seasonal salinas, Parartemia zietziana hatches at 20–40 g L-1 as the sites fill in late autumn-winter, passes through 2–3 cohorts in late winter-spring and then dies as the salinity rises rapidly in late spring-early summer [36, 37]. Much the same probably applies to similar seasonal salinas in southern SA and WA but involving various species according to lake type and locality [34, 35, 38]. In the central inland, salt lakes fill episodically often in summer, and in the Paroo, P. minuta hatches at low salinities, grows and reproduces, passing through one or more generations and persists as long as salinities do not exceed its upper tolerance limit [3, 39].

Parartemia zietziana eats mainly organic matter stirred from the bottom [31] and it is assumed other species feed in the same way. If so, it explains why there is rarely more than one species per lake, as there is no opportunity for size selection of particles and hence partitioning the resource as in the case of Branchinella feeding on diatoms [40].

The various species of Parartemia exhibit a range of characteristic lengths (Table 2). In a superficial assessment not accounting for factors such as food supply, growth temperature and salinity (in high salinities less energy is available for growth, see below), species occurring in the more reliably filling and longer lasting salinas in southern Australia generally are larger than those occurring in the short hydroperiods of episodic lakes of the inland [10]. How this is mediated is unknown, but it ensures species of the inland can mature early and reproduce before the site dries.

Marchant [37] in studying the energetics of P. zietziana in two lakes near Colac, Victoria (Pink: 80–240 g L-1; Cundare: 50 g L-1 to dry) assimilation was only 1631 kJ m-2 yr-1 in Pink Lake and 212 kJ m-2 yr-1 in Cundare. Pink Lake is of very low productivity [41] and Cundare probably even lower; allochthonous inputs appear to be the main source of energy [42]. In both lakes, on average, respiration accounted for 60–80% of assimilation. However respiration was often greater than assimilation and this imbalance lead to continuous mortality, variable growth and unpredictable recruitment. Gross growth efficiency (i.e. production/assimilation) of 15–30% was in the same range for other anostracans, but net growth efficiency (i.e. production/consumption) of 5–12% was well reduced. Although Parartemia is well adapted to live in salt lakes, life is difficult.

Halophilic Branchinella

While generally not being called brine shrimps, a few species of the freshwater genus Branchinella live in saline waters. Most notable among these is Branchinella simplex in salinas in the middle Goldfields of WA and B. buchananensis in some saline lakes in northwest NSW and inland Qld (Figure 1). The upper field salinity limit for B. simplex is 62 g L-1 and for B. buchananensis is 42 g L-1 [3]. Other species have much lower upper limits: B. compacta 15.9 g L-1, B. papillata 14 g L-1, B. nana 13 g L-1, B. nichollsi 12 g L-1, B. erosa and B. hearnii 12 g L-1, B. australiensis 11.2 g L-1, B. affinis 6.7 g L-1 and B. frondosa 4.2 g L-1 ([3], unpublished data). The occurrence of these species of Branchinella in saline lakes is no accident and is part of the normal succession of species in the lakes in which they occur, e.g. B. buchananensis in Lake Gidgee, the Paroo [3], Branchinella hearnii in the Unicup lakes near Manjimup, southwest WA (R. Hearn, pers. comm.), B. nana, B. nichollsi and B. simplex in Arrow Lake near Kalgoorlie [43] and B. simplex in Lake Carey, WA (B. Datson, pers. comm.). In some cases as the Unicup series there is no local Parartemia adapted to hyposaline waters and the waters do not exceed low salinities but in other cases such as in Gidgee Lake and Lake Carey the lake eventually becomes hypersaline and Parartemia assumes dominance. There is probably no competition between Branchinella and Parartemia as each eats different foods (see above) and it is purely a matter of salinity tolerance determining which is dominant.

Geddes [44] showed B. australiensis and B. compacta to be osmoconformers and presumably this applies to other species of Branchinella living in hyposaline waters. However it would be remarkable if this was the survival mechanism for B. buchananensis and B. simplex in mesosaline and hypersaline waters, respectively. To date the episodic occurrence of these species in remote salinas has mitigated against the solving of their osmoregulatory mechanism.

Four of the hyposaline Branchinella, B. australiensis, B. compacta, B. erosa and B. hearnii, have modifications to their posterior thorax, possibly to enhance species recognition by the male or contribute to lock and key mating [45]. Why these modifications should be almost confined to hyposaline species (one supposedly freshwater species, B. vosperi, has the posterior thorax modified) is unknown, but three (not B. hearnii) may come in contact with Parartemia which employs the lock and key mechanism in amplexus (see above), so they would be unable to connect in mating. In that B. vosperi was found within 100 m of hyposaline lakes with Parartemia, it is possible it also occurs in such lakes, but it was missed in totally inadequate collecting (author, unpublished data). By contrast, all freshwater species (except B. vosperi), despite common congeneric occurrences, lack female thoracic modifications, as according to this theory they never meet Parartemia.

Brine shrimps: conservation

A general perception is Parartemia spp. live in remote salt lakes well removed from human influences on the environment. This is not the case in the Western District of Victoria, Eyre Peninsula SA or the Wheatbelt of WA, where extensive land clearing is associated with grain farming, dairying or grazing. Also, some remote inland salt lakes are impacted by mining in WA.

In Victorian agricultural regions no change has been noted in the only species present, P. zietziana, possibly because its wide salinity tolerance masks changes in lake salinities. Certainly it now lives in Lake Corangamite where previous mesosaline conditions enabled predatory fish to survive. This change has been largely due to diversion of the main inflowing stream and hence an increase in salinity by evaporation [46]. On Eyre Peninsula, SA, lakes are salinising and Timms [35] predicts P. cylindifera will be replaced by the more tolerant P. zietziana. In WA there is extensive salinisation of lakes, so that populations of Parartemia spp. have been lost in many lakes [10]. The driving factors for this loss are not so much salinity increase, but associated acidification and changed hydrology from temporary seasonal to permanent waters [10]. Also in WA, there are a few lakes in the Goldfields where saline groundwater is discharged from mining activity. Despite concerns this may be inimical to hyposaline communities [46], this is not the case at least in Lake Carey (M. Coleman, pers. comm.).

At the species level, there are concerns for five species. Parartemia boomeranga naturally occurred over a small area, and it seems all the lakes in this area are now too salinised to support it, while P. extracta’s distribution has shrunk as lakes in its domain salinised [10]. These authors suggest both should be given an IUCN Vulnerable Status, but this has not been acted upon because of lack of sufficient evidence. In an effort to get such data for P. extracta, it seems it is safe in some core lakes in its distribution (A. Pinder, pers. comm.) and its known distribution has actually been expanded (author, unpublished data).

With just four known sites for P. mouritzi, two of which are mildly salinised, Timms et al. [10] suggested this be given local classification of WA DPAW Priority 1 species. Similarly, P. bicorna and the undescribed Parartemia sp. “e” occur in just one lake each, and a DPAW Priority 4 allocation is appropriate. These suggestions have not been acted upon because authorities want extensive field collections to prove these cases. This is difficult for extremely episodic and remote lakes. For instance, recently P. bicorna has been found in Lake Minigal (B. Datson, pers. comm) and Lake Ballard (R. Pedler, pers. comm.), both of which had filled for the first time in years and a collector had visited at a propitious time.

No recommendations have been made for species of Parartemia in other states, though they are considered safe enough in settled areas (Qld, NSW, Vic, Tas, SA) or their known occurrences are so remote (P. auriciforma, P. triquetra in SA, P. laticaudata in NT) that there are no concerns. The salt tolerant fairy shrimp, Branchinella buchananensis is considered endangered in New South Wales and under the Fisheries Management Act of 1994 it has been declared a vulnerable fish (!) species. It occurs in a few [47] known localities in the state and one of these contains an economic deposit of gypsum, which in the 1990s was proposed to be mined. The present owners of the lake are much more sympathetic to its ecology.

Conclusions

Australia has three genera and 32 species of anostracans in its saline lakes. The otherwise freshwater Branchinella is largely restricted to hyposaline waters. Most of its species probably osmoconform, but two at higher salinites may not. Native parthenogenetic Artemia is spreading into altered salinas, but introduced A. franciscana is not, despite predictions. Parartemia (19 species) generally hypo-osmoregulate almost as competently as Artemia but are restricted at very high salinities as they lack haemoglobin to function in the low oxygen environments. Populations can suffer continuous mortality through lack of food resources.

Mating in Parartemia is by lock and key amplexis, but why this should be so is not easily explained, given species almost never co-occur. Species are smaller where salinas have shorter hydrologies, perhaps an adaptation to increase the chances of maturation. The ecology of only one species has been extensively investigated; others may live differently, especially those in acid saline waters, an obvious gap in knowledge.

Many saline lakes in Australia are being modified, particularly in the Wheatbelt of WA, so that some species are at risk. Except for a species in NSW which has been designated a vulnerable fish (!), none has been protected, largely because authorities require more data and such are hard to get for species living in remote episodic sites.

Abbreviations

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- NT:

-

Northern Territory

- Qld:

-

Queensland

- SA:

-

South Australia

- Tas:

-

Tasmania

- WA:

-

Western Australia

- IUCN:

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature

- DPAW:

-

Department of Parks and Wildlife.

References

Abatzopoulos TJ, Beardmore JA, Sorgeloos P, Clegg JS: Artemia: Basic and Applied Biology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002.

Rogers DC: Anostraca catalogus (Crustacea: Branchiopodae). Raffles Bull Zool 2013, 61: 525–546.

Timms BV: Biodiversity of large branchiopods of Australian salt lakes. Curr Sci 2009, 96: 74–80.

McMaster K, Savage A, Finston T, Johnson MS, Knott B: The recent spread of Artemia parthenogenetica in Western Australia. Hydrobiologia 2007, 576: 39–48. 10.1007/s10750-006-0291-0

Maniatsi S, Baxevanis AD, Kappas I, Deligiannidis P, Triantafyllidis A, Papakostas S, Bougiouklis D, Abatzopoulos TJ: Is polyploidy a persevering accident or an adaptive evolutionary pattern? The case of the brine shrimp Artemia . Mol Phylogenet Evol 2011, 58: 353–364. 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.029

Williams WD, Geddes MC: Anostracans of Australian salt lakes, with particular reference to a comparison of Parartemia and Artemia . In Artemia Biology. Edited by: Browne RA, Sorgeloos P, Trotman CNA. Boston: CRC Press; 1991:351–367.

Geddes MC: Occurrence of the brine shrimp Artemia (Anostraca) in Australia. Crustaceana 1979,36(3):225–228. 10.1163/156854079X00690

Timms BV: Artemia in Australia. Anostr News 2006,12(1):1–2.

Ruebhart DR, Cock IR, Shaw GR: Invasive character of the brine shrimp Artemia franciscana Kellogg 1906 (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) and its potential impact on Australian inland hypersaline waters. Mar Freshw Res 2008, 59: 587–595. 10.1071/MF07221

Timms BV, Pinder A, Campagna V: The biogeography and conservation status of the Australian endemic brine shrimp Parartemia (Crustacea, Anostraca, Parartemiidae). Conserv Sci Western Aust 2009, 7: 413–427.

Browne RA, Sorgeloos P, Trotman CNA: Artemia Biology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991.

Clark LS, Bowen ST: The genetics of Artemia salina . VII Reproductive isolation. J Hered 1976, 67: 385–388.

Bowen ST, Burkin JP, Sterling G, Clark LS: Artemia haemoglobin: genetic variation in parthenogenetic and zygogenetic populations. Biol Bull 1978, 155: 273–287. 10.2307/1540952

Triantaphyllidis GV, Abatzopoulos TJ, Sorgeloos P: Review of the biogeography of the genus Artemia (Crustacea. Anostraca). J Biogeogr 1998, 25: 213–226. 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252190.x

Geddes MC: The brine shrimps Artemia and Parartemia in Australia. In The Brine Shrimp Artemia. Volume 3. Ecology, Culturing, Use in Agriculture. Edited by: Persoone G, Sorgeloos P, Roels O, Jaspers E. Wetteren, Belgium: Universa Press; 1980:57–65.

Geddes MC: The brine shrimps Artemia and Parartemia . Comparative physiology and distribution in Australia. Hydrobiologia 1981, 81/82: 169–179. 10.1007/BF00048714

Geddes MC, Williams WD: Comments on Artemia introductions and the need for conservation. In Artemia Research and Its Applications. Volume 3. Ecology, Culturing, Use in Aquaculture. Edited by: Sorgeloos P, Bengtson DA, Decleir W, Jaspers E. Wetteren, Belgium: Universa Press; 1987:19–26.

Sayce OA: The phyllopods of Australia, including a description of some new genera and species. Proc R Soc Vic 1903, 15: 224–261.

Daday E: Monographie systématique des Phyllopodes Anostracés. Ann Sci Nat B Zool 1910,11(9):91–489.

Weekers PH, Murugan G, Vanfleteren JR, Belk D, Dumont HJ: Phylogenetic analysis of anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) inferred from nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2002, 25: 535–544. 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00289-0

Linder F: Contributions to the morphology and taxonomy of the Branchiopoda Anostraca. Zool Bidr Upps 1941, 20: 101–303.

Geddes MC: Salinity tolerance and osmotic and ionic regulation in Branchinella australiensis and B. compacta (Crustacea: Anostraca). Comp Biochem Physiol A-Mol Integr Physiol 1973, 45A: 559–569.

Timms BV, Hudson P: The brine shrimps ( Artemia and Parartemia ) of South Australia, including descriptions of four new species of Parartemia (Crustacea: Anostraca: Artemiina). Zootaxa 2009, 2248: 47–68.

Timms BV: An identification guide to the brine shrimps of Australia. Vic Mus Sci Rep 2012, 16: 1–36.

Timms BV: An identification guide to the fairy shrimps (Crustacea: Anostraca) of Australia. In Identification and Ecology Guide No 47. Edited by: Hawking J. Thurgoona, NSW: CRCFC; 2004:1–76.

Remigio EA, Hebert PDN, Savage A: Phylogenetic relationships and remarkable radiation in Parartemia (Crustacea: Anostraca), the endemic brine shrimp of Australia: evidence from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Biol J Linn Soc 2001, 74: 59–71. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01377.x

Pinder AM, Halse SA, Shiel RJ, Cale DJ, McRae JM: Halophile aquatic invertebrates in the Wheatbelt region of south-western Australia. Vehr Int Verein Theor Angew Limnol 2002, 28: 1687–1694.

Rogers DC: The amplexial morphology of selected Anostraca. Hydrobiologia 2002, 486: 1–18. 10.1023/A:1021332610805

Geddes MC: Studies on the Australian brine shrimp Parartemia zietziana Sayce (Crustacea: Anostraca). II. Osmotic and ionic regulation. Comp Biochem Physiol A-Mol Integr Physiol 1975, 51A: 561–571.

Mitchell BD, Geddes MC: Distribution of the brine shrimp Parartemia zietziana Sayce and Artemia salina (L) along a salinity and oxygen gradient in a South Australian saltfield. Freshw Biol 1977, 7: 461–467. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1977.tb01695.x

Marchant R, Williams WD: Field measurements of ingestion and assimilation for the Australian brine shrimp Parartemia zietziana Sayce (Crustacea: Anostraca). Aust J Ecol 1977, 2: 379–390. 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1977.tb01153.x

Conte FP, Geddes MC: Acid brine shrimp: metabolic strategies in osmotic and ionic adaptation. Hydrobiologia 1988, 158: 191–200. 10.1007/BF00026277

Conte FP: Role of the C-4 pathway in crustacean chloride cell function. Am J Physiol 1980, 238: R269-R276.

Timms BV: A study of the saline lakes of the Esperance hinterland, Western Australia, with special reference to the roles of ground water acidity and episodicity. In Saline Lakes Around the World: Unique Systems with Unique Values. Natural Resources and Environmental Issues. Volume XV. Edited by: Oren A, Natfz D, Palacois P, Wurtsburgh WA. Logan, Utah, USA: S.J. and Jessie E. Quinney Natural Resources Research Library; 2009:214–224.

Timms BV: A study of the salt lakes and salt springs of Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. Hydrobiologia 2009, 626: 41–51. 10.1007/s10750-009-9736-6

Geddes MC: Seasonal fauna of some ephemeral saline waters in western Victoria with particular reference to Parartemia zietziana Sayce (Crustacea: Anostraca). Aust J Mar Freshw Res 1976, 27: 1–22. 10.1071/MF9760001

Marchant R: The energy balance of the Australian brine shrimp, Parartemia zietziana (Crustacea: Anostraca). Freshw Biol 1978, 8: 481–489. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1978.tb01470.x

Geddes MC, De Deckker P, Williams WD, Morton D, Topping M: On the chemistry and biota of some saline lakes in Western Australia. Hydrobiologia 1981, 81/82: 201–222. 10.1007/BF00048717

Timms BV: The biology of the saline lakes of the central and eastern inland of Australia: a review with special reference to their biogeographic affinities. Hydrobiologia 2007, 576: 27–37. 10.1007/s10750-006-0290-1

Timms BV, Sanders PR: Biogeography and ecology of Anostraca (Crustacea) in middle Paroo catchment of the Australian arid-zone. Hydrobiologia 2002, 486: 225–238. 10.1023/A:1021363104870

Hammer UT: Primary production in saline lakes: a review. Hydrobiologia 1981, 81/82: 47–57. 10.1007/BF00048705

Marchant R, Williams WD: Population dynamics and production of a brine shrimp Parartemia zietziana Sayce (Crustacea: Anostraca) in two salt lakes in western Victoria. Aust J Mar Freshw Res 1977, 28: 417–438. 10.1071/MF9770417

Chapman A, Timms BV: Waterbird usage of Lake Arrow, and arid zone wetland in the eastern Goldfields of Western Australia, following cyclonic rains. Aust Field Ornithol 2004, 21: 107–114.

Geddes MC: A new species of Parartemia (Anostraca) from Australia. Crustaceana 1973, 25: 5–12. 10.1163/156854073X00443

Timms BV: Six new species of brine shrimp Parartemia Sayce (Crustacea: Anostraca: Artemiina) in Western Australia. Zootaxa 2010, 2715: 1–35.

Timms BV: Salt lakes in Australia: present problems and prognosis for the future. Hydrobiologia 2005, 552: 1–15. 10.1007/s10750-005-1501-x

Timms BV: Saline Lakes of the Paroo, inland New South Wales, Australia. Hydrobiologia 1993, 267: 269–289. 10.1007/BF00018808

Acknowledgements

I thank Adrian Pinder, Bindy Datson, Geraldine Janicke, Ilias Kappas, Jim Lane, Mark Coleman, Peri Coleman, Reece Pedler and Roger Hearn for sharing their unpublished data with me or at conferences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Timms, B. A review of the biology of Australian halophilic anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca). J of Biol Res-Thessaloniki 21, 21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2241-5793-21-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2241-5793-21-21