Abstract

This article introduces ‘Tox-Box’, a joint research project designed to develop a holistic approach towards a harmonized testing strategy for exposure- and hazard-based risk management of anthropogenic trace substances in drinking water to secure a long-term drinking water supply. The main task of the Tox-Box consortium is to enhance the existing health-related indicator value concept (German: GOW-Konzept - Gesundheitlicher Orientierungswert) through development and prioritization of additional end point-related testing strategies for genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, germ cell damage, and endocrine effects. In this context, substance-specific modes of action will be identified and characterized. Toxicological data collected by the 12 Tox-Box subprojects will be evaluated and weighted to structure a hierarchical testing strategy for an improved risk assessment. A technical guidance document for exposure and hazard-based risk management of anthropogenic trace substances in drinking water will eventually be prepared.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Artikel stellt das Verbundprojekt “Tox-Box” vor, das einen ganzheitlichen Ansatz für eine harmonisierte Teststrategie eines Expositions-bezogenen und Gefahren-basierten Risikomanagements von anthropogenen Spurenstoffen in Trinkwasser entwickeln und somit einen Beitrag zur langfristigen Sicherung der Trinkwasserversorgung leisten soll. Die Hauptaufgabe des Tox-Box-Konsortiums ist die Weiterentwicklung des bestehenden GOW-Konzeptes (Gesundheitlicher Orientierungswert) durch Erforschung und Priorisierung zusätzlicher Endpunkt-bezogener Teststrategien für Gentoxizität, Neurotoxizität, Keimzellschädigung und endokrine Effekte. In diesem Kontext werden zudem Substanz-spezifische Wirkmechanismen identifiziert und charakterisiert. Im Anschluss werden die toxikologischen Daten aus den 12 Teilprojekten evaluiert und gewichtet um eine hierarchische Teststrategie für eine verbesserte Risikobewertung zu erstellen. Zum Abschluss des Projektes wird eine technische Richtlinie für ein Expositions-bezogenes und Gefahren-basiertes Risikomanagement von anthropogenen Spurenstoffen im Trinkwasser erstellt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Water is the largest and most important natural resource on Earth. The approximate global water supplies add up to 1.4 billion cubic kilometers. However, the major portion consists of saltwater in the oceans and glacier ice. Only a minor portion is immediately available for drinking water use. As a consequence, drinking water supplies are generally vulnerable to a multitude of natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Climate change, excessive consumption, contamination, or other forms of water abuse by industries and agriculture already lead to water shortages in several regions of the world, even of the western hemisphere. Despite numerous advances of regulatory measures such as the new European chemical policy REACH [1] and the EU Water Framework Directive [2], an increasing number of anthropogenic pollutants have been identified in water bodies. Provision of sufficient amounts of non-polluted water has thus become a major challenge to societies throughout the world. Potential pollutants come from a wide range of chemical families; a selection of highly relevant substances is presented in Table 1. For the majority of these substances, toxicological and ecotoxicological data are scarce or even lacking.

As diverse as the classes of substances, as different are their pathways into the water cycle. The impact on surface water and groundwater may come from point sources such as industrial discharges or the discharge from sewage treatment plants [8] or from diffuse sources such as effluents of agricultural activities or surface runoff.

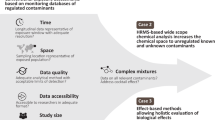

Given the increasing number of drinking water-relevant but toxicologically unknown anthropogenic micropollutants, the focus of research programs must clearly be set on a hazard-based risk assessment and, therefore, the development of acute and mechanism-specific bioassays to identify the alleged damage potential. Currently, the only concept to assess these substances is the health-related indicator value (HRIV) approach developed by the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

The following is the general introduction to the HRIV (German: Gesundheitlicher Orientierungswert (GOW)) approach.

Drinking water directives like the German ‘Trinkwasserverordnung’ regulate the concentration of some chemicals in drinking water. However, due to the large number of different chemicals that might be found in drinking water, it is virtually impossible to regulate all compounds. The main reason for this is that only limited or no toxicological data on most substances are available. Nevertheless, these substances have to be evaluated once they appear in drinking water. Whenever possible, acceptable daily intake, tolerable daily intake (TDI) or reference dose (RfD) values are the basis for an evaluation. In case none of these values is available, information on biological end points like genotoxicity or neurotoxicity is taken into account. Structural alerts for genotoxicity can also form the basis for an evaluation. For deriving the HRIV (GOW), it is assumed that the drinking water consumption is 2 L/day and per person for 70 years. Consuming drinking water under these conditions will not lead to health-related concerns because the precautionary principle is the basis of the evaluation. When no data at all are available, the substance in question is considered genotoxic and the initial HRIV is 0.1 μg/L (Figure 1). For substances with known genotoxicity and metabolic relevance in humans, the HRIV is set to 0.01 μg/L. Three HRIVs can be allocated to non-genotoxic substances: neuro- or immunotoxic compounds (0.3 μg/L), chemicals with subchronic toxicity (1.0 μg/L), and compounds that induce chronic toxicity (3.0 μg/L). Regardless of how an HRIV for a compound is derived, the concept itself is always hierarchical with genotoxicity as the most important criterion. It is important to note that a higher HRIV can only be set when it is known that a compound is not liable for a lower HRIV. If for example a chemical is known to be neurotoxic but no information is available on its genotoxicity, the HRIV must be 0.1 μg/L, not 0.3 μg/L. Once more detailed information on a given substance becomes available, the HRIV may be modified. Due to the fact that a worst-case scenario is assumed, i.e., the compound is considered genotoxic, a new HRIV will always be higher than the previous one. This also avoids the obligation to set more restrictive cutoff values when additional information becomes available.

So far, the HRIV concept is rather theoretical and defines biological end points like genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and subchronic and chronic toxicity, but it does not devise the experimental approach to obtain toxicological data. The aim of the project “Tox-Box” is therefore, to identify and establish in vitro assays that allow a fast and reliable toxicological evaluation of known and emerging trace substances. It is part of the funding scheme ‘Risk Management of Emerging Compounds and Pathogens in the Water Cycle (RiSKWa)’ introduced to the public by Huckele and Track [9].

Aims

Currently, no standardized holistic concept for the risk assessment of anthropogenic trace substances in drinking water is available. Although toxicological end points are described in the HRIV concept, technical guidance defining the experimental approaches to obtain the toxicological data is still missing.

Many trace substances (e.g., pharmaceuticals, herbicides, and industrial chemicals) are in an area of conflict between risk (adverse effects) and benefit (health and productivity) for humans as well as the environment, thus requiring an accurate and reliable risk assessment. This will be achieved by expanding the existing HRIV concept to include additional end points concerning endocrine effects, neurotoxicity, genotoxicity, and germ cell damage. With these enhancements, an improved risk assessment including regulation and mitigation of drinking water pollution will be ensured. In order to determine necessary thresholds, substance-specific modes of action are very important. Hence, risk management will be based on actual exposure-based risk potentials, which are studied by use of biological assays.

As an overall objective, Tox-Box will deliver a harmonized testing strategy concerning an exposure- and hazard-based risk management of anthropogenic trace substances laid down in a guidance document. Moreover, in late 2014, all data collected so far will be presented at a symposium in Germany, and the results will be discussed with renowned international scientists. The international scale of the final symposium emphasizes again the particular relevance of drinking water security not only for Germany, but also for Europe and the world - especially since the holistic approach of Tox-Box (Figure 2) is worldwide unique.

Project structure

The project Tox-Box aims to achieve its research goals in four phases arranged over a period of almost 4 years, beginning in 2011 and ending in 2014.

The first phase contains the establishment and validation of the biological test systems by each of the 12 project partners. Every module (exposure, neurotoxicity, genotoxicity, and endocrine effects) has to prioritize, develop, and define end point-related testing strategies within its scientific area. In parallel, a preliminary list of drinking water-relevant trace substances for testing is established. On its internet platform (http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/wasser/themen/trinkwasser/toxbox/index.htm), the project communicates to the public and provides information on current and future activities.

Selection of relevant single substances is finalized in the second phase of the project and routine testing is initialized. The validated and standardized bioassays should detect potential threats to humans and the environment. Through the different end points of the four modules, a holistic risk assessment of these substances is achieved. In the further course of phase two, a new technique to concentrate bulk water samples is developed by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), Leipzig, Germany, which has recently also been used for a Europe-wide inter-laboratory study on the use of bioassays for water monitoring programs organized by the bioassay working group of the European Norman Network on emerging pollutants [10]. The method should help to achieve better identification and characterization of relevant trace substances in large volumes of complex water samples. After evaluating the results for the single substances in all four modules, highly concentrated bulk water samples are tested with the same bioassays during the third phase of the project. Based on biometrical evaluation of the entire data sets and the evaluation and optimization of the test protocols, the prioritization, development, and determination of end point-based testing strategies will take place.

Following these bioassays with drinking water-relevant single substances and these biological tests with real water samples, risk assessment criteria will be derived for the HRIV concept in the fourth and final phase of the project. Thus, criteria will be based on hierarchical test strategies for hazard-based exposure scenarios of anthropogenic trace substances in drinking water. In addition to the resulting guidance document, further information material and specific training programs will be developed and provided for public use.

Project consortium

The consortium conducting the Tox-Box project consists of 12 partners (subprojects (SP)) including UBA. As the coordinating institution, the UBA organizes meetings, allocation of substances, and collection of data and is responsible for the internet presence of the project. The project partners are grouped into four modules: exposure, genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and endocrine effects, subsequently presented below with their contributing members and specific project tasks.

Module exposure

Since the concentrations of most emerging chemicals which can be found in drinking water are several orders of magnitude below the concentrations used in standard test systems, new ways of increasing the concentrations of these chemicals have to be found. The procedures used routinely in chemical analysis have to be adapted to the needs of bioassays that will be used for risk assessment:

-

SP1 Microbiology Department of the water laboratory, RheinEnergie AG, Cologne (Meike Kramer, Carsten Schmidt, Eva-Maria Prantl). They are responsible for the organization of a testing program that enables the validation of a suitable test battery for the evaluation of individual compounds on the basis of the health-related indicator value as recommended by the German Drinking Water Commission for safe lifelong exposure.

-

SP2 Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Department of Effect-Directed Analysis (Arnold Bahlmann, Tobias Schulze, Martin Krauss, Werner Brack). They are responsible for the collection and extraction of large volume water samples of up to 1,000 L using an automated solid-phase extraction device and chemical analysis by liquid chromatography-high resolution tandem mass spectrometry.

Module genotoxicity

Due to their relation to carcinogenicity, mutagenicity and genotoxicity in general are major aspects for the risk assessment of substances, metabolites, and transformation products in drinking and surface water. In Germany, the Federal Environment Agency and the German Association for Water, Wastewater and Waste recommend the application of lower health-related guidance or benchmark values for genotoxic substances. Speed and accuracy to identify or exclude a risk to humans are fundamental requirements for the use in daily routine monitoring. Consequently, six subprojects test different bioassays for the standardized evaluation of genotoxicity of single substances and complex water samples. These include bacterial tests as well as test systems with eukaryotic vertebrate cell lines (V79 in vitro micronucleus assay according to OECD 487 [11] and mouse lymphoma assay according to OECD 476 [12]). An increasing complexity and relevance to humans will be achieved with metabolic activation by human enzymes expressed in the target cells and with monitoring of activation of the transcription factor NF-кB, which is relevant for inflammation, immune responses, and cell survival in human cells. Analysis with zebra fish embryos is used as a surrogate for whole organism assays and for the comparability of fish to mammalian cell lines. In the following, the specificities of the genotoxicity assays used are briefly illustrated:

-

SP3 Microbiology Department of the water laboratory, RheinEnergie AG, Cologne (Meike Kramer, Carsten Schmidt, Eva-Maria Prantl). They are responsible for the detection of genotoxic effects using two in vitro short-term bacterial tests. Point mutations will be analyzed using the Ames fluctuation test according to OECD Guideline 471 [13] and ISO 11350. The umu test according to ISO 13829 will be used to quantify the intensity of DNA repair. In order to complement these standard procedures, additional bacterial tester strains genetically engineered for expressing human biotransformation enzymes will be used to increase the detectable activity spectrum.

-

SP4 German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Department of Radiation Biology, Research Group Astrobiology (Petra Rettberg, Elke Rabbow). They are responsible for the detection and quantification of genotoxic effects using the Switch test, a short-term assay based on recombinant bacteria. In Salmonella typhimurium TA1535-pSwitch, the luminescence genes of Photobacterium leiognathi as reporter genes are under the control of a DNA damage-dependent promoter, resulting in a damage-dependent and, therefore, dose-dependent increase in bioluminescence [14–18].

-

SP5 Hydrotox GmbH, Freiburg (Martina Knauer, Stefan Gartiser). They are responsible for the performance of highly standardized and in the context of chemical registration well-established genotoxicity tests with mammalian cell lines according to OECD guidelines like the ‘In vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test’ [11] or the ‘In vitro Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation Test’ [12]. Tests are performed close to the quality standards applied for chemical registration.

-

SP6 German Institute of Human Nutrition (DIfE) Potsdam-Rehbrücke, Department of Nutritional Toxicology (Walter Meinl, Sabine Unger, Hansruedi Glatt). They are responsible for the usage of cell lines genetically engineered for human biotransformation enzymes [19, 20] in genotoxicity studies of contaminants in drinking water, with the aims of increasing the test sensitivity and of improving the relevance of the test results.

-

SP7 German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Department of Radiation Biology, Research Group Cellular Biodiagnostics (Christa Baumstark-Khan, Christine E. Hellweg, Luis Spitta and Sebastian Feles). They are responsible for the activation of the NF-κB pathway, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity response in mammalian cells. The activation of the NF-κB pathway and cellular proliferation are quantified by the amounts of fluorescent proteins (EGFP, DsRed, tdTomato) produced in genetically modified mammalian cell lines. This bioassay will reveal possible cytotoxic, genotoxic, and inflammatory effects at the cellular level in response to environmental samples [21–27].

-

SP8 Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Department of Bioanalytical Ecotoxicology, Leipzig, Germany (Patrick Renner and Eberhard Küster). They are responsible for the analysis of lethal and sublethal effects of single substances and mixtures of genotoxins on the zebra fish (Danio rerio) embryo. In addition, effects and reactions of the zebra fish after genotoxin exposure to the proteome will be analyzed via usage of 2D differential in-gel electrophoresis techniques.

Module neurotoxicity

Neurotoxicity plays an important role in toxicological risk assessment and will be analyzed at two complementary physiological levels: in vitro with cell lines and in vivo with zebra fish (D. rerio) embryos as a model organism. The aim is to establish a combined test battery which deals with the subject of neurotoxicity within the HRIV concept:

-

SP9 Federal Environment Agency (UBA), Section Drinking Water and Swimming Pool Water Toxicology, Bad Elster, Germany (Alexander Eckhardt, Ralf Junek, Rita Heinze, Tamara Grummt). They are responsible for the detection of different cytotoxic and neurotoxic effects in cell culture, using HepG2 liver cells and SH SY5Y nerve cells. In a first set of experiments, basic parameters like oxidative stress, apoptosis, and necrosis are quantified. Using a real-time cell analyzer (RTCA™), a time course of the cells’ impedance is done, thereby analyzing growth rate and changes in cell shape. Finally, SH SY5Y cells are grown in an air-conditioned microscope, which allows for the observation of proper neural differentiation.

-

SP10 Aquatic Ecology & Toxicology Section, Centre for Organismal Studies (COS), University of Heidelberg (Daniel Stengel, Thomas Braunbeck). They are responsible for the development of a neurotoxicological test battery with zebra fish (D. rerio) using three sensory systems (olfaction [28], vision [29], and lateral line [30]), one synaptic system (cholinergic transmission), and a major physiological end point (embryo toxicity). State-of-the-art imaging techniques and an enzyme assay are used to detect neurotoxic effects in vivo[31–33].

Module endocrine effects

Endocrine activity of environmental samples has become a major concern for both man and wildlife within the last decades [34, 35]. National and international agencies are in the process of establishing testing programs and strategies to assess the safety of currently used chemicals with regard to their potential to interact with the endocrine systems of man and wildlife, resulting in potential impacts on reproduction, growth, and/or development.

Consequently, two subprojects will analyze and establish endocrine activity as an important, additional toxicological mode of action within the HRIV concept using several in vitro and in vivo biotests described as follows:

-

SP11 Incos Boté GmbH - Cosmetical, Pharmaceutical And Toxicological Contract Research Laboratory And Consultancy (Petra Waldmann, Birgit Kneib-Kissinger, Walter Schadenboeck). They are responsible for the detection of endocrine effects using the ER/AR recombinant yeast system for receptor-mediated endocrine activity.

-

SP12 Institute for Environmental Research - Biology V, RWTH Aachen University (Jochen Kuckelkorn, Thomas-Benjamin Seiler, Regine Redelstein, Sibylle Maletz, Henner Hollert). They are responsible for the detection of several endocrine effects using the ERα/AR CALUX assay for estrogen and androgen receptor-mediated endocrine activity in the human cell line ERα/AR CALUX [36], the H295R assay for changes in the steroidogenesis of the human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line H295R [37], and the in vivo reproduction toxicity assay with the mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum for endocrine effects at an individual and population level [38].

References

Commission of the European Communities: Regulation (EC) no 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) establishing a European chemicals agency. Official Journal of the European Communities; 2006.

Commission of the European Communities: Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Communities; 2000.

Benotti MJ, Trenholm RA, Vanderford BJ, Holady JC, Stanford BD, Snyder SA: Pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. drinking water. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43: 597–603. 10.1021/es801845a

Ternes TA, Meisenheimer M, McDowell D, Sacher F, Brauch HJ, Gulde BH, Preuss G, Wilme U, Seibert NZ: Removal of pharmaceuticals during drinking water treatment. Environ Sci Technol 2002,36(17):3855–3863. 10.1021/es015757k

Reemtsma T, Weiss S, Mueller J, Petrovic M, Gonzales S, Barcelo D, Ventura F, Knepper TP: Polar pollutants entry into the water cycle by municipal wastewater: a European perspective. Environ Sci Technol 2006, 40: 5451–5458. 10.1021/es060908a

Vierke L, Staude C, Biegel-Engler A, Drost W, Schulte C: Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) main concerns and regulatory developments in Europe from an environmental point of view. Environ Sci Eur 2012, 24: 16. 10.1186/2190-4715-24-16

Kuch HM, Ballschmiter K: Determination of endocrine-disrupting phenolic compounds and estrogens in surface and drinking water by HRGC-(NCI)-MS in the picogram per liter range. Environ Sci Technol 2001, 35: 3201–3206. 10.1021/es010034m

Triebskorn R, Amler K, Blaha L, Gallert C, Giebner S, Güde H, Henneberg A, Hess S, Hetzenauer H, Jedele K, Jung RM, Kneipp S, Köhler HR, Krais S, Kuch B, Lange C, Löffler H, Maier D, Metzger J, Müller M, Oehlmann J, Osterauer R, Peschke K, Raizner J, Rey P, Rault M, Richter D, Sacher F, Scheurer M, Schneider-Rapp J, et al.: SchussenAktiv plus : reduction of micropollutants and of potentially pathogenic bacteria for further water quality improvement of the river Schussen, a tributary of Lake Constance. Germany Environmental Sciences Europe 2013, 25: 2. 10.1186/2190-4715-25-2

Huckele S, Track T: Risk management of emerging compounds and pathogens in the water cycle (RiSKWa). Environ Sci Eur 2013, 25: 1. 10.1186/2190-4715-25-1

Brack W, Dulio V, Slobodnik J: The NORMAN Network and its activities on emerging environmental substances with a focus on effect-directed analysis of complex environmental contamination. Environ Sci Eur 2012, 24: 29. 10.1186/2190-4715-24-29

OECD: Test No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010.

OECD: Test No. 476: In vitro Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation Test. Paris: OECD Publishing; 1997.

OECD: Test No. 471: Bacterial Reverse Mutation Tes. Paris: OECD Publishing; 1997.

Rettberg P, Bandel K, Baumstark-Khan C, Horneck G: Increased sensitivity of the SOS-LUX-Test for the detection of hydrophobic genotoxic substances with Salmonella typhimurium TA1535 as host strain. Anal Chim Acta 2001,426(2):167–173. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)00823-0

Rabbow E, Rettberg P, Baumstark-Khan C, Horneck G: The SOS-LUX-LAC-FLUORO -Toxicity test on the International Space Station (ISS). In Space Life Sciences: Biodosimetry, Biomarkers and Late Stochastic Effects of Space Radiation. Edited by: Hei TK, Wu HL. Oxford; Pergamon; 2003:1513–1524.

Rabbow E, Rettberg P, Baumstark-Khan C, Horneck G: SOS-LUX- and LAC-FLUORO-TEST for the quantification of genotoxic and/or cytotoxic effects of heavy metal salts. Anal Chim Acta 2002,456(1):31–39. 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01594-X

Baumstark-Khan C, Rabbow E, Rettberg P, Horneck G: The combined bacterial Lux-Fluoro test for the detection and quantification of genotoxic and cytotoxic agents in surface water: Results from the “Technical Workshop on Genotoxicity Biosensing”. Aquat Toxicol 2007,85(3):209–218. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.09.003

Baumstark-Khan C, Cioara K, Rettberg P, Horneck G: Determination of geno- and cytotoxicity of groundwater and sediments using the recombinant SWITCH test. J Environ Sci Heal A 2005,40(2):245–263. 10.1081/ESE-200045529

Glatt H, Schneider H, Liu YG: V79-hCYP2E1-hSULT1A1, a cell line for the sensitive detection of genotoxic effects induced by carbohydrate pyrolysis products and other food-borne chemicals. Mutat Res-Gen Tox En 2005,580(1–2):41–52.

Glatt H, Pabel U, Meinl W, Frederiksen H, Frandsen H, Muckel E: Bioactivation of the heterocyclic aromatic amine 2-amino-3-methyl-9H-pyrido 2,3-b indole (MeA alpha C) in recombinant test systems expressing human xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes. Carcinogenesis 2004,25(5):801–807.

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C, Horneck G: Enhanced green fluorescent protein as reporter protein for biomonitoring of cytotoxic effects in mammalian cells. Anal Chim Acta 2001,427(2):191–199. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)01021-7

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C, Rettberg P, Horneck G: Suitability of enhanced green fluorescent protein as a reporter component for bioassays. Anal Chim Acta 2001,426(2):175–184. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)00824-2

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C, Horneck G: Generation of stably transfected mammalian cell lines as fluorescent screening assay for NF-kappa B activation-dependent gene expression. J Biomol Screen 2003,8(5):511–521. 10.1177/1087057103257204

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C: Detection of UV-induced activation of NF-kappa B in a recombinant human cell line by means of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Radiat Environ Biophys 2007,46(3):269–279. 10.1007/s00411-007-0104-5

Hellweg CE, Langen B, Klimow G, Ruscher R, Schmitz C, Baumstark-Khan C, Reitz G: Up-stream events in the nuclear factor kappa B activation cascade in response to sparsely ionizing radiation. Adv Space Res 2009,44(8):907–916. 10.1016/j.asr.2009.07.009

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C, Schmitz C, Lau P, Meier MM, Testard I, Berger T, Reitz G: Carbon-ion-induced activation of the NF-kappa B pathway. Radiat Res 2011,175(4):424–431. 10.1667/RR2423.1

Hellweg CE, Baumstark-Khan C, Schmitz C, Lau P, Meier MM, Testard I, Berger T, Reitz G: Activation of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway by heavy ion beams of different linear energy transfer. Int J Radiat Biol 2011,87(9):954–963. 10.3109/09553002.2011.584942

Blechinger SR, Kusch RC, Haugo K, Matz C, Chivers DP, Krone PH: Brief embryonic cadmium exposure induces a stress response and cell death in the developing olfactory system followed by long-term olfactory deficits in juvenile zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2007,224(1):72–80. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.06.025

Poggi L, Vitorino M, Masai I, Harris WA: Influences on neural lineage and mode of division in the zebrafish retina in vivo . Journal of Cell Biology 2005,171(6):991–999. 10.1083/jcb.200509098

Froehlicher M, Liedtke A, Groh KJ, Neuhauss SCF, Segner H, Eggen RIL: Zebrafish ( Danio rerio ) neuromast: promising biological endpoint linking developmental and toxicological studies. Aquat Toxicol 2009,95(4):307–319. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.04.007

Lin CC, Hui MNY, Cheng SH: Toxicity and cardiac effects of carbaryl in early developing zebrafish ( Danio rerio ) embryos. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2007,222(2):159–168. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.013

Kuester E, Altenburger R: Comparison of cholin- and carboxylesterase enzyme inhibition and visible effects in the zebra fish embryo bioassay under short-term paraoxon-methyl exposure. Biomarkers 2006,11(4):341–354. 10.1080/13547500600742136

Kuester E: Cholin- and carboxylesterase activities in developing zebrafish embryos ( Danio rerio ) and their potential use for insecticide hazard assessment. Aquat Toxicol 2005,75(1):76–85. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.07.005

World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): An Assessment of the State of the Science of Endocrine Disruptors Prepared by a Group of Experts for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and WHO. Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2012:2013.

Hecker M, Hollert H: Endocrine disruptor screening: regulatory perspectives and needs. Environ Sci Eur 2011,23(15):1–14.

Legler J, van den Brink CE, Brouwer A, Murk AJ, van der Saag PT, Vethaak AD, van der Burg P: Development of a stably transfected estrogen receptor-mediated luciferase reporter gene assay in the human T47D breast cancer cell line. Toxicol Sci 1999,48(1):55–66. 10.1093/toxsci/48.1.55

Hollert H, Giesy J: The OECD validation program of the H295R steroidogenesis assay for the identification of in vitro inhibitors and inducers of testosterone and estradiol production. Phase 2: Inter-laboratory pre-validation studie. Environ Sci Pollut R 2007,14(1):23–30. 10.1065/espr2007.03.402

Duft M, Schmitt C, Bachmann J, Brandelik C, Schulte-Oehlmann U, Oehlmann J: Prosobranch snails as test organisms for the assessment of endocrine active chemicals - an overview and a guideline proposal for a reproduction test with the freshwater mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum . Ecotoxicology 2007,16(1):169–182. 10.1007/s10646-006-0106-0

Acknowledgements

The project Tox-Box is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (funding number 02WRS1282I). Tox-Box is a constitutive part of the BMBF action plan ‘Sustainable water management (NaWaM)’ and is integrated in the BMBF frame program ‘Research for sustainable development FONA’. It is part of the funding scheme ‘Risk Management of Emerging Compounds and Pathogens in the Water Cycle (RiSKWa)’ introduced to the public by Huckele and Track [9]. Contract period: October 2011 to September 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JK (RWTH Aachen University) and TG (UBA), who is responsible for the general design of the project, wrote the introductory parts of the manuscript. The other authors - AB, CBK, WB, TB, SF, SG, HG, RH, CEH, HH, RJ, MK (Hydrotox GmbH), BKK, MK (RheinEnergie AG), MK (UFZ), EK, SM, WM, AN, EMP, ER, RR, PR, WS, CS, TS, TBS, LS, DS, PW, AE- contributed with specific information concerning their respective methods. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Grummt, T., Kuckelkorn, J., Bahlmann, A. et al. Tox-Box: securing drops of life - an enhanced health-related approach for risk assessment of drinking water in Germany. Environ Sci Eur 25, 27 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-4715-25-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-4715-25-27