Abstract

In past decades, cancer patient survival has been improved with earlier detection and advancements in therapy. However, many patients who exhibit no clinical symptoms after frontline therapy subsequently suffer, often many years later, aggressive tumor recurrence. Cancer recurrence represents a critical clinical challenge in effectively treating malignancies and for patients’ quality of life. Tumor cell dormancy may help to explain treatment resistance and recurrence or metastatic reactivation. Understanding the dormant stage of tumor cells may help in discovering ways to maintain the dormant state or permanently eliminate dormant residual disseminated tumor cells. Over the past decade, numerous studies indicate that various mechanisms of tumor dormancy exist, including cellular dormancy (quiescence), angiogenic dormancy, and immunologic dormancy. In this short review, we summarize recent experimental and clinical evidence for these three mechanisms and other possible tumor microenvironment mechanisms that may influence tumor dormancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tumor dormancy is a recognized clinical phenomenon in which disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) remain occult, asymptomatic, and undetectable over a prolonged period of time. Dormancy can occur at the earliest stage of tumor development but also when remnant tumor cells escape treatment. Tumor dormancy may contribute to tumor progression and relapse, either locally or metastatically at distant sites, years or decades after treatment. Clinical dormancy is frequently observed in many types of tumors, such as breast cancer (BC) [1], prostate cancer (PC) [2, 3], melanoma [4, 5], and B-cell lymphoma [6, 7]. Dormant cells are characterized by their slow growth, their ability to escape frontline treatment and host immunity, and their capability to self-renew. A clinical study showed that non-proliferating cancer cells could persist during chemotherapy and were detected more frequently in BC patients with progressive disease than in patients with primary BC [8].

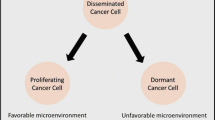

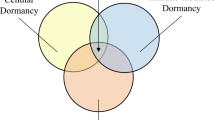

Three molecular mechanisms involved in tumor dormancy have been identified: cellular dormancy (quiescence or mitotic arrest), angiogenic dormancy (limited tumor size), and immunologic dormancy (immunosurveillance, balance between clearance and proliferation) (Figure 1). The mechanisms that regulate the transition between the dormant and proliferating states are largely unknown. In addition, no dormancy markers have been well characterized. Here, we review recent findings of relevant genetic abnormalities, novel discoveries regarding tumor dormancy, and possible mechanistic links. This information should help in the development of appropriate study models and improve therapeutic approaches to prevent disease recurrence.

Mechanisms in tumor dormancy. Tumor dormancy can lead to tumor recurrence locally or to metastasis at a distant site. Dormancy can be induced by more than one mechanism: cellular dormancy (quiescence), angiogenic dormancy (tumor mass size limit), and immunologic dormancy (immunosurveillance, balance between proliferation and apoptosis). Others mechanisms, such as epigenetic change, tumor microenvironment, CSCs, EMT, and miRNA, also may involve in tumor dormancy. A tumor microenvironment that is altered (such as by frontline treatment) can mediate tumor cell entrance into, maintenance, and exit from dormancy through interaction with cells at niches, such as endothelial cells, stroma, or immune cells.

Cellular dormancy

Cellular dormancy is a state in which cells are in a quiescent state (the G0 phase). These cells do not enter the normal proliferating cell cycle. Their growth arrest is reversible and under certain conditions, such as induction by growth factors, cytokines, nutrients, or chemical agents, the cells can re-enter the cell cycle to proliferate again. Quiescent normal adult stem cells serve as a source of self-renewal in the maintenance of multiple adult epithelial tissues. In contrast, quiescence in a heterogeneous cancer population likely contributes to cancer cell survival in response to anti-cancer agents and radiotherapy, leading to disease recurrence [9–11].

In patients with prolonged clinical dormancy, the presence of dormant cells is often identified by their lack of the cellular proliferation marker Ki-67 as well as the lack of apoptotic markers [12–14]. Cellular DNA/RNA content analysis is commonly used to assess for cells in the G0 phase, as indicated by 2 N DNA ploidy and reduced RNA content. In contrast, cells in the G1/S/G2 phase exhibit 2 N/4 N DNA and higher RNA content [15].

Several cell cycle regulators are known to directly or indirectly mediate cell quiescence. The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p27Kip1 and p21 can cooperate to maintain a balance between hematopoietic stem cell dormancy and proliferation at certain cell-cell interactions at tumor microenvironmental niches [16]. For example, cell adhesion of lymphoma cells to bone marrow (BM) stromal cells was shown to lead to reversible cell cycle arrest through upregulation of posttranscriptional levels of p27Kip1 and p21 through activation of the APC/CDH1 ubiquitin ligase complex [17]. In addition, APC/CDH1 increased the ubiquitination and degradation of Skp2 (part of the p21 and p27 inhibitor, SCF) and subsequently reduced the level and ubiquitination and degradation of p27Kip1, which resulted in cell cycle arrest (Figure 2a).

Role of cell cycle regulators in the cellular dormancy (“intrinsic dormancy”) mechanism. (a) In the “typical” cell cycle pathway, upregulation of CDK inhibitors, such as p21 and p27, can inhibit cells from entering the cell cycle by downregulating cyclin/CDK activation. In this scenario, cells can enter into a quiescent state (G0). The ubiquitin ligase APC/CDH1 enhances the upregulation of p21/p27 expression by increasing the degradation of Skp2 (one of the units that constitute SCF, a p21/p27/p57 inhibitor). (b) The DREAM complex in the quiescent state (G0). MuvB recruits and interacts with p130 (RB-like), E2F4, and dimerization partner (DP), forming the DREAM complex. DYRK phosphorylates MuvB and activates the DREAM complex, which triggers cells to become quiescent. DYRK also stabilizes p27Kip1 through phosphorylation and prevents cells from moving into the G1 phase by reducing the expression of cyclin D.

Besides the APC/CDH1-SKP-p27Kip1/p21 signaling pathway, the multi-subunit DREAM complex was recently indicated as a critical regulator of quiescence. This complex consists of a dimerization partner, a Retinoblastoma (RB)-like pocket protein (p130, encoded by RB-like 2 or p107, encoded by RB-like 1), E2F protein, and mutil-vulval class B protein (MuvB). The MuvB core component is essential for coordinating cell cycle; it recruits, binds, and directs key transcription factors to the promoters of periodic cell cycle genes during various phases of the cell cycle [18]. During quiescence and with a high expression level of p130, MuvB binds to p130, E2F, and the dimerization partner to form the DREAM complex and repress all cell cycle-dependent expression [18–20] (Figure 2b). Impairing various components of the DREAM complex by mutation or RNA interference leads to disruption of cell cycle-dependent repression of genes, such as p107/p130 and E2F4/E2F5, during quiescence. The expression level of p107 is high only in proliferating cells, but knockdown of p130 results in increased expression of p107, which results in the formation of a p107-DREAM complex in quiescent cells. However, p130-/-/p107-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts lose the ability to form a functional DREAM complex and fail to repress E2F-dependent genes expression during quiescence, causing cells to re-enter the cell cycle [21]. E2F4-/-/E2F5-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts can also re-enter the cell cycle from quiescence but fail to arrest in the G1 phase when the CDK inhibitor INK4A is overexpressed [22].

Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase (DYRK), a serine/threonine kinase, maintains quiescence by activating the DREAM complex. DYRK1A and DYRK1B contribute to the phosphorylation of the MuvB subunit LIN52 at serine 28, which promotes interaction between the MuvB core and p130-E2F during quiescence [23]. Knockdown or disruption of DYRK1A activity leads to reduced levels of MuvB phosphorylation and assembly of the DREAM complex [23]. DYRK1B can stabilize p27Kip1 [24] and increase the turnover of cyclin D isoforms [25], thereby preventing cells from entering the cell cycle and thus maintaining their quiescence (Figure 2b).

In summary, a balance between quiescent DREAM complex and proliferative complexes, the MuvB-BMYB-FOXM1 complex and the typical RB-cyclin/CDK-dependent complex, is critical to maintain quiescence. Modulating functions of the DREAM complex in synchrony with anti-proliferative treatments may provide a novel therapeutic approach to primary cancer treatment and relapse prevention.

Angiogenic dormancy

Once DTCs exit from quiescence and proliferate to reach a certain tumor mass size that requires more than the normal tissue vasculature can provide, the tumor mass induces angiogenesis to meet its nutrient demands. However, some tumor cells lack this angiogenic capacity and are therefore unable to grow beyond a certain size. These cells are controlled by a balance between cellular proliferation and apoptosis and remain clinically undetectable, resulting in angiogenic dormancy. The transition from a pre-vascular tumor to a highly vascularized and progressively growing tumor is known as the “angiogenic switch” [26]. The balance between pro-angiogenic factors (such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and angiopoietin) and anti-angiogenic factors (such as thrombospondin (TSP), endostatin, vasculostatin, and angiostatin) plays a role in the angiogenic switch of dormant cells (Figure 3).

Angiogenic dormancy (“extrinsic dormancy”) at niches. At niches, dormancy can be induced through signaling between DTCs, endothelial cells, and stroma with both upregulation and downregulation of multiple factors and signaling axes. DTCs enter dormancy with a vascular structure that is stable and non-angiogenic. In contrast, a sprouting vascular structure triggers tumor cells to exit from dormancy following an “angiogenic switch” in microenvironment, leading to tumor outgrowth and recurrence or metastasis. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CXCL12, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12; EGFR, epithelial growth factor receptors; ESM-1, endothelial specific marker 1; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; HSP27, heat shock protein 27; IGFBP5, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5; LTBPs, latent transforming growth factor β binding protein; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; VEGFs, vascular endothelial growth factors.

A recent xenograft model study with U-87 human glioblastoma cells in SCID mice indicated that the balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors is associated with the dormancy or aggressiveness of tumor growth [27]. The “aggressive” clones of U-87 cells formed larger and vascularized tumor masses, whereas the “dormant” clones formed smaller and avascular tumor masses. Compared with aggressive clone tumor cells, these dormant clones expressed high levels of TSP, angiomotin, and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 and low levels of endothelial cell-specific marker 1 and epithelial growth factor receptor. In addition, the dormant clone tumor cells exhibited impaired angiogenesis and slower invasion.

In a BC xenograft study, heat shock protein 27 (HSP27) was identified as a key player in the balance between tumor dormancy and outgrowth with the onset of angiogenesis [28]. Reduced HSP27 protein expression in angiogenic cancer cells led to a low secretion level of pro-angiogenic factors (such as VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and basic fibroblast growth factor), which resulted in poorer proliferation and migration of cancer cells and effectively suppressed tumor growth and angiogenesis. In contrast, overexpression of HSP27 in non-angiogenic cancer cells promoted tumor growth in vivo. For BC or melanoma patients, a low expression level of HSP27 protein was associated with less aggressive tumors and improved patient survival [28].

Chemokine signaling directs certain tumor cells to specific organs that provide a supportive microenvironment with cytokines or chemokines, tumor-derived secreted factors, and tumor-specific homing-regulated receptors through cross-talk among metastatic tumor cells, stroma, and organ-derived cells. This environment determines whether DTCs survive, proliferate, become dormant, or undergo apoptotic cell death. This niche may be not required for recurrence or metastasis, but they do promote recurrent and metastatic progression, and support tumor cell colonization.

Gap junctional intercellular communication between BC cells and bone marrow (BM) stroma can facilitate BC dormancy. A subset of BC cells with the properties of dormancy, including chemoresistance, cycling quiescence, asymmetric division, and highly invasive capability, is responsible for gap junctional intercellular communication with BM stroma [29]. Interaction between BM stroma-derived CXCL12 and BC-expressing CXCR4 or CXCR7 receptors can direct BC cells from circulation into BM stromal niches, causing BC cells to become quiescent in the BM stroma [30].

Recently, a unique organotypic microvascular niche model demonstrated that endothelial-derived TSP-1 and endothelial-derived perlecan maintain BC cells in a quiescent state and suppress tumor growth [31, 32]. Other extracellular matrix molecules, such as laminin, type IV collagen, and latent transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) binding protein (LTBP), also contribute to dormant niches [33]. That study showed that the sprouting of neovasculature disrupted vascular homeostasis at dormant niches, which led to the loss of suppressive signals. Sequentially, extracellular matrix molecules and growth factors promote micro-metastatic outgrowth of BC cells.

TGF-β/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling between bone stromal cells and PC cells at bone niches also mediates the balance between the dormancy of PC cells and metastasis [34]. Secreted from bone stromal cells, BMP7 interacts with the BMP receptor 2 of PC cells; this interaction activates p38, p21, and NDRG1, thereby inducing dormancy. In a mouse model, BMP7 injection significantly limited tumor growth, whereas inhibition of BMP7 increased bone metastasis. In addition, in PC patients, upregulation of BMP receptor 2 expression correlated with the extent that bone was free of metastasis.

The anti-adhesion matrix component LTBP-2 is also associated with pre-metastatic niches for dormancy [33]. Low LTBP-2 expression levels were observed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cell lines and tumor samples from NPC patients. Overexpression of LTBP-2 induced dormancy and inhibited NPC cell migration and angiogenesis through the reduction of VEGF, which led to attenuated tumor formation. In contrast, inhibition of TGF-β/BMP signaling, such as by overexpression of Coco (a secreted antagonist of TGF-β ligands), induced the exit of BC cells from dormancy, specifically in the lung niches, leading to metastatic outgrowth [35].

Osteopontin (OPN) is involved in leukemic dormancy in BM niches and in the persistence of minimal residual disease after chemotherapy. During circulation and migration, proliferating acute lymphoblastic leukemia blasts express high levels of OPN receptors, such as VLA-4, and then specifically adhere to stroma-derived OPN, which is secreted by osteoblasts at endosteal niches. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia blasts also secrete OPN into the local microenvironment. With additional niche-specific microenvironmental factors in BM, leukemic blasts return to dormancy, resulting in resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and eventually tumor recurrence. Neutralization of OPN triggers dormant cells to re-enter the cell cycle, sensitizing them to chemotherapeutic agents [36].

In summary, in the tumor microenvironment or pre-metastatic niches, communication between cancer cells and cells at the niches is critical to the regulation of DTC dormancy and to the angiogenic switch with neovascular structure homeostasis. A particular challenge is to develop appropriate clinical models to identify the biomarkers and therapeutic targets in angiogenic-dormant tumor cells. Three-dimensional co-culture systems with tissue-like morphology may provide the best advantage for investigating the mechanisms of angiogenic dormancy in the tumor microenvironment [27].

Immunologic dormancy

Immunity also contributes to tumor dormancy under an equilibrium condition with immunologic clearance. How DTCs enter into, maintain, and exit from this immunologic dormancy is poorly understood. Immunity can control tumor cells through three distinct processes: elimination, equilibrium, and escape (Figure 4). Elimination functions as an extrinsic tumor suppressor in naïve hosts in which innate and adaptive immunity work together to detect and destroy transformed cells before they become clinically symptomatic. Certain DTC variants may not be completely eliminated, but their net growth is restricted by immunity control, resulting in an equilibrium state and maintenance of tumor cells in dormancy. These DTCs may induce a host-protective immune response, or their antigen expression (recognized by adaptive immunity via T-cell effectors) may be modified to adapt to the host immune system. Over a prolonged period, the constant interaction of immunity with DTCs may edit the immunogenicity of dormant tumor cells, causing them to enter into an attenuated immunogenic state. This attenuated state leads to the escape process. The edited DTCs begin to grow progressively in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and eventually become clinically detectable and lead to tumor recurrence [37–39].

Immunologic dormancy (“equilibrium dormancy”) at niches. The immune system can control tumor cells through elimination, equilibrium, or escape. DTCs can enter dormancy during equilibrium states. Over years, environmental factors change or the genomic stability of DCTs changes, allowing dormant cells to escape (this state is called immunosurveillance) and reactivate to grow. At niches, immune cells, stroma, and endothelial cells can secret mitogens, immunosuppressive factors, and angiogenic factors that modify the tumor microenvironment and trigger cells to exit from dormancy and lead to recurrence or metastasis. CTL, cytotoxic T-lymphocytes; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; INFγ, Interferon gamma; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; NK, natural killer; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; TREG, regulatory T-cells.

Direct or indirect modulation of the immune system in the tumor microenvironment can enhance the escape of tumor cells from dormancy. For example, DTCs can directly attenuate the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response by reducing T-cell activation, promoting DTC resistance to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-induced apoptosis, or altering tumor-associated antigen presentation to antigen-presenting cells [40, 41]. Numerous immune cell types may enhance indirect escape from dormancy through their infiltration into the tumor microenvironment; these cell types include myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T-cells, and tumor-associated macrophages [27, 42, 43]. These cells can secret numerous mitogens, cytokines, and some angiogenic factors to promote angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and immunosuppression [40]. For example, interleukins 23 and 12 were shown to play critical and opposing roles in immunologic dormancy in a mouse model of methycholanthrene-induced fibrosarcoma [44]. Interleukin 23 can suppress both innate and adaptive anti-tumor effectors responses, whereas interleukin 12 prevents cancer outgrowth [44, 45].

Immunologic dormancy may rely on the high genomic instability of DTCs. Once dormant DTCs accumulate genomic aberrations years or decades after radiotherapy or chemotherapy, genomic instability generates a less immunogenic phenotype that can better evade anti-tumor immunity, resulting in reactivation of these cells. Genome or exome sequencing analysis of unedited and edited DTCs may reveal mutations involved in the process of exit from dormancy as a consequence of genomic instability. Specific mutations in these edited tumor cells may lead to altered expression of tumor-specific antigens for T-cells, and these antigens could serve as immunotherapeutic targets.

Other potential mechanisms in tumor dormancy

Several other mechanisms may play roles in tumor dormancy, such as genetic and epigenetic changes, cancer stem cells, tumor microenvironment, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and non-coding RNA manipulation. Epigenetic modification by DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase within DTCs may mediate the expression of genes that trigger cells to enter into, maintain, or exit from dormancy. For example, altered tumor-associated antigen expression through epigenetic change in DTCs may lead to the escape of these cells from immunity and reactivate their growth. Epigenetic change also may regulate quiescence through the nontraditional RB/p27 pathway.

CSCs have similar properties as dormant cells, including slow growth, escape frontline treatment and host immunity, and capability to self-renew. However, whether cancer stem cells involve in tumor dormancy is controversial. One group identified a population of slow-cycling BC cells with retained metabolism labeling. These cells exhibited increasing capability of chemotherapy resistance and leading to tumor recurrence in CSC-independent model [46]. In contrast, one subset of BC with CSC marker (Oct4hi/CD44hi/med/CD24-/+) and properties can facilitate dormancy in pre-metastatic niches [29]. Prostate CSCs with senescence reversibility in BMP7-dependent manner contribute dormancy in bone [27].

Stress signaling or suppressive signals in the tumor microenvironment may reverse the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor cells and induce tumor cells into dormancy or quiescence. However, a subsequent angiogenic switch or altered immunity eventually reactivates dormant tumor cells, resulting in tumor recurrence. Tumor microenvironment also facilitates a switch between proliferation and dormancy by the balance between two mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 signaling pathways [47–50]. Angiogenesis-associated mitogen-activated protein kinase (uPAR) functions as a central regulator of the ratio of ERK/p38. Loss of uPAR signaling from tumor microenvironment results in stress signaling with low ERK and high p38 activities, which in turn lead to dormancy. In contrast, tumor microenvironment shift may lead to reactivate uPAR signaling following high ERK and low p38 activities, which can reactivate dormant cells, leading to recurrence and metastasis [51].

Non-coding RNAs were recently identified as potential biomarkers in human cancers. A single microRNA (miRNA) molecule can affect the expression of hundreds of genes and numerous signaling pathways [52, 53]. miRNA may affect dormancy through various pathways. For example, miRNA-190 is upregulated in dormancy-prone glioblastomas and osteosarcomas, and it mediates several transcriptional factors, tumor suppressor genes, and interferon response pathways [27]. In summary, epigenetic modification or non-coding RNAs may be able to regulate dormancy. Epigenetic and non-coding RNA microarray techniques could help identify potential dormancy regulators and pathways. However, developing study models and distinguishing between dormant and heterogeneous tumor populations are complicated and challenging tasks.

Kim and colleagues recently published a gene signature for tumor cell dormancy that was based on results from two clinical studies on tumor cell quiescence or angiogenic failure [36]. The 49-gene signature they developed represents a dormancy score, which is based on upregulated and downregulated genes in dormant cells [54]. The researchers applied the dormancy score to human BC samples from four microarray studies and concluded that estrogen receptor-positive tumors had a higher dormancy score, which correlated with a low proportion of metastasis, whereas estrogen receptor-negative tumor had a lower dormancy score, which correlated with a higher proportion of metastasis. Whether this gene signature is actually associated with dormancy and recurrence/metastasis and whether it could serve as a tumor dormancy biomarker need to be confirmed with an appropriate dormancy model.

The DNA damage repair response, especially the pathway that responds to DNA double-strand breaks, may protect dormant tumor cells from radiotherapy or chemotherapy. An example is the non-homologous end joint (NHEJ) pathway. In this pathway, the broken ends are directly ligated without the need for a homologous template, in contrast to homologous recombination. While the homologous recombination pathway is error free, the NHEJ pathway is error prone. As DNA damage accumulates in DTCs following cancer treatment, NHEJ may be upregulated to repair these damages and allow tumor cells to survive; however, this pathway also creates genomic instability in the tumor cells. In certain microenvironments, these genomically unstable DTCs may become dormant, maintain dormancy, or eventually reactivate, becoming more aggressive and leading to cancer recurrence. This idea needs to be tested in vitro and in vivo with an appropriate dormancy model.

Conclusion

Several mechanisms and pathways involved in regulating tumor cell dormancy have recently been identified. However, most of these mechanisms are not specific to dormancy. In addition, the lack of suitable model systems for detecting and maintaining the dormant state creates challenges in designing systematic studies on dormancy either in vitro or in vivo. Continued investigation and discovery are needed to identify dormancy signatures and biomarkers as well as the therapeutic targets and windows for “secondary” cancer prevention after primary treatment has failed. Better understanding of tumor cell dormancy will lead to novel detection techniques in the clinic and therapeutic options to prevent deadly tumor recurrence and metastasis.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BM:

-

Bone marrow

- BMP:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CDKs:

-

Cyclin-dependent kinases

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- DTC:

-

Disseminated tumor cell

- DYRK:

-

Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase

- HSP27:

-

Heat shock protein 27

- LTBP:

-

Latent transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) binding protein

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- MuvB:

-

Mutil-vulval class B protein

- NHEJ:

-

Non-homologous end joint

- NPC:

-

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- OPN:

-

Osteopontin

- PC:

-

Prostate cancer

- TGF-β:

-

Transforming growth factor β

- TSP:

-

Thrombospondin

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

Meng S, Tripathy D, Frenkel EP, Shete S, Naftalis EZ, Huth JF, Beitsch PD, Leitch M, Hoover S, Euhus D, Haley B, Morrison L, Fleming TP, Herlyn D, Terstappen LW, Fehm T, Tucker TF, Lane N, Wang J, Uhr JW: Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10: 8152–8162.

Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC: Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999, 281: 1591–1597.

Amling CL, Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Seay TM, Slezak J, Zincke H: Long-term hazard of progression after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: continued risk of biochemical failure after 5 years. J Urol 2000, 164: 101–105.

Faries MB, Steen S, Ye X, Sim M, Morton DL: Late recurrence in melanoma: clinical implications of lost dormancy. J Am Coll Surg 2013, 217: 27–34. discussion 34–26

Callaway MP, Briggs JC: The incidence of late recurrence (greater than 10 years); an analysis of 536 consecutive cases of cutaneous melanoma. Br J Plast Surg 1989, 42: 46–49.

Davis TA, Maloney DG, Czerwinski DK, Liles TM, Levy R: Anti-idiotype antibodies can induce long-term complete remissions in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma without eradicating the malignant clone. Blood 1998, 92: 1184–1190.

Press OW, Leonard JP, Coiffier B, Levy R, Timmerman J: Immunotherapy of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2001, 2001: 221–240.

Muller V, Stahmann N, Riethdorf S, Rau T, Zabel T, Goetz A, Janicke F, Pantel K: Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: correlation to bone marrow micrometastases, heterogeneous response to systemic therapy and low proliferative activity. Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11: 3678–3685.

Patrikidou A, Chabaud S, Ray-Coquard I, Bui BN, Adenis A, Rios M, Bertucci F, Duffaud F, Chevreau C, Cupissol D, Domont J, Perol D, Blay JY, Le Cesne A, French Sarcoma G: Influence of imatinib interruption and rechallenge on the residual disease in patients with advanced GIST: results of the BFR14 prospective French Sarcoma Group randomised, phase III trial. Ann Oncol 2013, 24: 1087–1093.

Boichuk S, Parry JA, Makielski KR, Litovchick L, Baron JL, Zewe JP, Wozniak A, Mehalek KR, Korzeniewski N, Seneviratne DS, Schoffski P, Debiec-Rychter M, Decaprio JA, Duensing A: The DREAM Complex Mediates GIST Cell Quiescence and Is a Novel Therapeutic Target to Enhance Imatinib-Induced Apoptosis. Cancer Res 2013, 73: 5120–5129.

Mellor HR, Ferguson DJ, Callaghan R: A model of quiescent tumour microregions for evaluating multicellular resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Br J Cancer 2005, 93: 302–309.

Rameshwar P: Breast cancer cell dormancy in bone marrow: potential therapeutic targets within the marrow microenvironment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010, 10: 129–132.

Hou JM, Krebs MG, Lancashire L, Sloane R, Backen A, Swain RK, Priest LJ, Greystoke A, Zhou C, Morris K, Ward T, Blackhall FH, Dive C: Clinical significance and molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor microemboli in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30: 525–532.

Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH, Brandt B: Detection, clinical relevance and specific biological properties of disseminating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8: 329–340.

Zbigniew Darzynkiewicz GJ, Edward F: Srour: differential staining of DNA and RNA. Current Protocols in Cytometry 2004.

Zou P, Yoshihara H, Hosokawa K, Tai I, Shinmyozu K, Tsukahara F, Maru Y, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Suda T: p57(Kip2) and p27(Kip1) cooperate to maintain hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through interactions with Hsc70. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9: 247–261.

Lwin T, Hazlehurst LA, Dessureault S, Lai R, Bai W, Sotomayor E, Moscinski LC, Dalton WS, Tao J: Cell adhesion induces p27Kip1-associated cell-cycle arrest through down-regulation of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase pathway in mantle-cell and other non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas. Blood 2007, 110: 1631–1638.

Sadasivam S, Decaprio JA: The DREAM complex: master coordinator of cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13: 585–595.

Schmit F, Korenjak M, Mannefeld M, Schmitt K, Franke C, von Eyss B, Gagrica S, Hanel F, Brehm A, Gaubatz S: LINC, a human complex that is related to pRB-containing complexes in invertebrates regulates the expression of G2/M genes. Cell Cycle 2007, 6: 1903–1913.

Sadasivam S, Duan S, DeCaprio JA: The MuvB complex sequentially recruits B-Myb and FoxM1 to promote mitotic gene expression. Genes Dev 2012, 26: 474–489.

Hurford RK Jr, Cobrinik D, Lee MH, Dyson N: pRB and p107/p130 are required for the regulated expression of different sets of E2F responsive genes. Genes Dev 1997, 11: 1447–1463.

Gaubatz S, Lindeman GJ, Ishida S, Jakoi L, Nevins JR, Livingston DM, Rempel RE: E2F4 and E2F5 play an essential role in pocket protein-mediated G1 control. Mol Cell 2000, 6: 729–735.

Litovchick L, Florens LA, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, DeCaprio JA: DYRK1A protein kinase promotes quiescence and senescence through DREAM complex assembly. Genes Dev 2011, 25: 801–813.

Besson A, Gurian-West M, Chen X, Kelly-Spratt KS, Kemp CJ, Roberts JM: A pathway in quiescent cells that controls p27Kip1 stability, subcellular localization, and tumor suppression. Genes Dev 2006, 20: 47–64.

Deng X, Ewton DZ, Friedman E: Mirk/Dyrk1B maintains the viability of quiescent pancreatic cancer cells by reducing levels of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res 2009, 69: 3317–3324.

Sun W: Angiogenesis in metastatic colorectal cancer and the benefits of targeted therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2012, 5: 63.

Satchi-Fainaro R, Ferber S, Segal E, Ma L, Dixit N, Ijaz A, Hlatky L, Abdollahi A, Almog N: Prospective identification of glioblastoma cells generating dormant tumors. PLoS ONE 2012, 7: e44395.

Straume O, Shimamura T, Lampa MJ, Carretero J, Oyan AM, Jia D, Borgman CL, Soucheray M, Downing SR, Short SM, Kang SY, Wang S, Chen L, Collett K, Bachmann I, Wong KK, Shapiro GI, Kalland KH, Folkman J, Watnick RS, Akslen LA, Naumov GN: Suppression of heat shock protein 27 induces long-term dormancy in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109: 8699–8704.

Patel SA, Ramkissoon SH, Bryan M, Pliner LF, Dontu G, Patel PS, Amiri S, Pine SR, Rameshwar P: Delineation of breast cancer cell hierarchy identifies the subset responsible for dormancy. Sci Rep 2012, 2: 906.

Lim PK, Bliss SA, Patel SA, Taborga M, Dave MA, Gregory LA, Greco SJ, Bryan M, Patel PS, Rameshwar P: Gap junction-mediated import of microRNA from bone marrow stromal cells can elicit cell cycle quiescence in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 2011, 71: 1550–1560.

Ghajar CM, Peinado H, Mori H, Matei IR, Evason KJ, Brazier H, Almeida D, Koller A, Hajjar KA, Stainier DY, Chen EI, Lyden D, Bissell MJ: The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nature cell biology 2013, 15: 807–817.

Franses JW, Baker AB, Chitalia VC, Edelman ER: Stromal endothelial cells directly influence cancer progression. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3: 66ra65.

Chen H, Ko JM, Wong VC, Hyytiainen M, Keski-Oja J, Chua D, Nicholls JM, Cheung FM, Lee AW, Kwong DL, Chiu PM, Zabarovsky ER, Tsao SW, Tao Q, Kan R, Chan SH, Stanbridge EJ, Lung ML: LTBP-2 confers pleiotropic suppression and promotes dormancy in a growth factor permissive microenvironment in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2012, 325: 89–98.

Buijs JT, Rentsch CA, van der Horst G, van Overveld PG, Wetterwald A, Schwaninger R, Henriquez NV, Ten Dijke P, Borovecki F, Markwalder R, Thalmann GN, Papapoulos SE, Pelger RC, Vukicevic S, Cecchini MG, Lowik CW, van der Pluijm G: BMP7, a putative regulator of epithelial homeostasis in the human prostate, is a potent inhibitor of prostate cancer bone metastasis in vivo. Am J Pathol 2007, 171: 1047–1057.

Gao H, Chakraborty G, Lee-Lim AP, Mo Q, Decker M, Vonica A, Shen R, Brogi E, Brivanlou AH, Giancotti FG: The BMP inhibitor Coco reactivates breast cancer cells at lung metastatic sites. Cell 2012, 150: 764–779.

Boyerinas B, Zafrir M, Yesilkanal AE, Price TT, Hyjek EM, Sipkins DA: Adhesion to osteopontin in the bone marrow niche regulates lymphoblastic leukemia cell dormancy. Blood 2013, 121: 4821–4831.

Vesely MD, Schreiber RD: Cancer immunoediting: antigens, mechanisms, and implications to cancer immunotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013, 1284: 1–5.

Quesnel B: Dormant tumor cells as a therapeutic target? Cancer Lett 2008, 267: 10–17.

Koebel CM, Vermi W, Swann JB, Zerafa N, Rodig SJ, Old LJ, Smyth MJ, Schreiber RD: Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature 2007, 450: 903–907.

Hensel JA, Flaig TW, Theodorescu D: Clinical opportunities and challenges in targeting tumour dormancy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013, 10: 41–51.

Gelao L, Criscitiello C, Fumagalli L, Locatelli M, Manunta S, Esposito A, Minchella I, Goldhirsch A, Curigliano G: Tumour dormancy and clinical implications in breast cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2013, 7: 320.

Quesnel B: Tumor dormancy and immunoescape. APMIS 2008, 116: 685–694.

Wu X, Peng M, Huang B, Zhang H, Wang H, Huang B, Xue Z, Zhang L, Da Y, Yang D, Yao Z, Zhang R: Immune microenvironment profiles of tumor immune equilibrium and immune escape states of mouse sarcoma. Cancer Lett 2013, 340: 124–133.

Teng MW, Vesely MD, Duret H, McLaughlin N, Towne JE, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ: Opposing roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in maintaining occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Cancer Res 2012, 72: 3987–3996.

Langowski JL, Zhang X, Wu L, Mattson JD, Chen T, Smith K, Basham B, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Oft M: IL-23 promotes tumour incidence and growth. Nature 2006, 442: 461–465.

Moore N, Houghton J, Lyle S: Slow-cycling therapy-resistant cancer cells. Stem Cells Dev 2012, 21: 1822–1830.

Sosa MS, Avivar-Valderas A, Bragado P, Wen HC, Aguirre-Ghiso JA: ERK1/2 and p38alpha/beta signaling in tumor cell quiescence: opportunities to control dormant residual disease. Clin Cancer Res 2011, 17: 5850–5857.

Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Ossowski L, Rosenbaum SK: Green fluorescent protein tagging of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 pathways reveals novel dynamics of pathway activation during primary and metastatic growth. Cancer Res 2004, 64: 7336–7345.

Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Estrada Y, Liu D, Ossowski L: ERK(MAPK) activity as a determinant of tumor growth and dormancy; regulation by p38(SAPK). Cancer Res 2003, 63: 1684–1695.

Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Liu D, Mignatti A, Kovalski K, Ossowski L: Urokinase receptor and fibronectin regulate the ERK(MAPK) to p38(MAPK) activity ratios that determine carcinoma cell proliferation or dormancy in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 2001, 12: 863–879.

Allgayer H, Aguirre-Ghiso JA: The urokinase receptor (u-PAR)–a link between tumor cell dormancy and minimal residual disease in bone marrow? APMIS 2008, 116: 602–614.

Hassan O, Ahmad A, Sethi S, Sarkar FH: Recent updates on the role of microRNAs in prostate cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2012, 5: 9.

Fernando TR, Rodriguez-Malave NI, Rao DS: MicroRNAs in B cell development and malignancy. J Hematol Oncol 2012, 5: 7.

Kim RS, Avivar-Valderas A, Estrada Y, Bragado P, Sosa MS, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Segall JE: Dormancy signatures and metastasis in estrogen receptor positive and negative breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7: e35569.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth L. Hess and Edward Wang for manuscript editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SHW drafted and coordinated the manuscript. SHW and SYL read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Sh., Lin, SY. Tumor dormancy: potential therapeutic target in tumor recurrence and metastasis prevention. Exp Hematol Oncol 2, 29 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2162-3619-2-29

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2162-3619-2-29