Abstract

Pain remains a significant problem for patients hospitalized in intensive care units (ICUs). As research has shown, for some of these patients pain might even persist after discharge and become chronic. Exposure to intense pain and stress during medical and nursing procedures could be a risk factor that contributes to the transition from acute to chronic pain, which is a major disruption of the pain neurological system. New evidence suggests that physiological alterations contributing to chronic pain states take place both in the peripheral and central nervous systems. The purpose of this paper is to: 1) review cutting-edge theories regarding pain and mechanisms that underlie the transition from acute to chronic pain, such as increases in membrane excitability of peripheral and central nerve fibers, synaptic plasticity, and loss of the function of descending inhibitory pain fibers; 2) provide information on the association between the immune system and pain and its crucial contribution to development of chronic pain syndromes, and 3) discuss mechanisms at brain levels in the nervous system and their contribution to affective (i.e., emotional) states associated with chronic pain conditions. Finally, we will offer suggestions for ICU clinical interventions to attempt to prevent the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Most, if not all, patients in intensive care units (ICUs) will experience pain at some point during their ICU stay related to their injury, surgery, burns, or comorbidities, such as cancer,and/or from the myriad procedures performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes [1–4]. Indeed, even medical patients experience substantial pain at rest [5]. Despite increased attention to assessment and pain management,pain remains a significant problem for ICU patients [1, 6–8].

Unrelieved pain in adult ICU patients is far from benign. Medical and surgical ICU patients who recalled pain and other traumatic situations while in the ICU (27% of 80 patients) had a higher incidence of chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms than did a comparative group of ICU patients [9]. Indeed, concurrent or past pain may be the greatest risk factor for development of chronic pain [4, 10]. Despite clinical concerns about the contribution of ICU hospitalization to development of chronic pain, a systematic review of the literature on quality of life (QOL) after hospitalization in an ICU concluded that chronic pain in ICU survivors did not differ from a matched normal population [11], except in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(ARDS) [12].

Nevertheless, recent findings from studies in various ICU patient populations as well as with longer follow-up periods are in keeping with the findings for chronic pain in patients with ARDS. Patients discharged from a medical-surgical ICU reported higher bodily pain at 12 months after hospitalization compared with 3 months [13]. For patients with burns hospitalized in an ICU, the majority of responders (79% of patients) suffered from moderate to severe pain 1 year after the injury [14]. Furthermore, a group of German researchers found highly significant differences in the pain intensity and pain interference between survivors of severe sepsis compared with a healthy German population [15]. However, others have not confirmed these findings in ICU survivors of sepsis in the Netherlands [16].

When the follow-up of the patients after hospitalization in an ICU was even longer, such as 2 years after major surgery, almost 60% of patients reported having moderate or extreme problems in usual activities: 56% had pain, and 56% had mobility problems [17]. Similarly, patients hospitalized in a medical-surgical ICU had higher bodily pain reports 5 years after discharge compared with 3 months [18]. Importantly, according to the findings of a recent study with a mean follow-up of 8 (range, 6–11) years, nearly half of all patients hospitalized in an ICU for all surgical classifications combined still had problems with cognition (43%), mobility (52%), and pain/discomfort (57%) [19].

Despite methodological problems with these studies, mainly small sample of patients, no homogeneity of pain measures, and high mortality rate or loss to follow-up, the observations for severe functional limitations combined with high reports of pain even years after ICU discharge grant further exploration. Important questions to ask are: Why does acute pain transition into a chronic pain state in some patients? Might medical and/or nursing procedures performed during the ICU stay, or other painful stimuli experienced by patients in ICUs, be contributing factors to the neurological mechanism of the transition?

Today, we know more about the physiological mechanisms of acute pain as well as mechanisms of acute-to-chronic pain. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to emphasize the risk that exists for ICU patients and others in developing chronic pain as a result of an acute pain experience. To do so, we will: 1) review cutting-edge theories regarding pain and mechanisms that underlie the transition from acute to chronic pain, such as increases in membrane excitability of peripheral and central nerve fibers, synaptic plasticity, and loss of the function of descending inhibitory pain fibers; 2) provide information on the association between the immune system and pain and its crucial contribution to development of chronic pain syndromes; and 3) discuss mechanisms at supraspinal levels in the nervous system and their contribution to affective (i.e., emotional) states associated with chronic pain conditions. As we address these three issues, we will be able to offer suggestions for clinical interventions to attempt to prevent the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Terminology used to describe the phases of the transition from acute to chronic pain

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) describes pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” [20]. Acute pain can arise from cutaneous (i.e., from the skin), deep somatic (i.e., from muscle, bone) or visceral structures (i.e., from organs within the chest and abdomen) [21]. When unexpected exposure to potentially harmful stimuli occurs, pain manifests as an automatic (reflex) withdrawal response along with a motivational reaction, most frequently a feeling of unpleasantness (i.e., a negative affect) [22]. The sensory process of detecting the “actual or potential tissue damage” is called nociception and clinically manifests as hypersensitivity to mechanical (e.g., pressure applied to an abdominal incision during coughing), thermal (e.g., heat from burns), or chemical stimuli (e.g., when inflammatory substances are released during an injury). (See Table 1 for definitions of hypersensitivity and other terms used in this review.) The hypersensitivity at the site of the injury that is associated with acute pain motivates the patient to avoid further damage [23, 24] and, thus, is protective of tissues and the organism [25]. Yet, this hypersensitivity may cause delayed mobilization if the ICU patient is in too much pain [26]. In the context of injury (e.g., trauma, surgery), acute pain might persist for a few hours or days or even for up to several months and is still considered acute [27].

Peripheral sensitization is usually the result of exposure of nociceptors (i.e., receptors that respond to a noxious stimulus) to inflammatory products and mediators of tissue injury. This subsequently contributes to reductions in nerve thresholds at nociceptive terminals, increases in sensitivity, and amplification of the excitability of the peripheral afferent nerve fibers [32]. Whereas this action can last for an extended period of time, it is not permanent [34]. Under normal circumstances, peripheral hypersensitivity returns to normal when inflammation subsides or the source of the injury is removed. Consider, for example, the sensitivity of a surgical incision that decreases over a matter of days.

However, in certain instances, pain can exceed the average period of healing, cease serving any apparent protective function, and become chronic (i.e., after 2 to 3 months) [34, 35]. In these cases, peripheral hypersensitivity does not return to normal. On the contrary, it indirectly contributes to the initiation of central sensitization; i.e., sensitization of the spinal cord nerves. During central sensitization, nociceptive-specific neurons may progressively increase their response to repeated nonpainful stimuli, develop spontaneous activity, and increase the area of the body that is involved with the pain [36]. The hyperalgesia of central sensitization usually develops as part of ongoing pathology (i.e., damage to peripheral or central nerve fibers, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis) and is considered maladaptive. Furthermore, hyperalgesia can be induced by opioid administration and/or interruption, although this phenomenon is not well understood yet [37]. Judicious treatment of pain in the ICU may help to preempt development of central sensitization. This is important, because once this type of sensitization occurs for prolonged periods, it can be maintained by lower or different kind of inputs to the central nervous system (CNS). This is identified as neuropathic pain, or pain caused by damage to peripheral or central nerve fibers themselves.

Mechanisms involved in the transition from acute to chronic pain increases in membrane excitability of peripheral nerve fibers

Peripheral neurons that respond to noxious stimuli and serve to detect potentially harmful thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimuli are called nociceptors [38]. There are two main types of nociceptors: medium-diameter myelinated Aδ afferents that mediate acute pain that occurs quickly and is well localized; and small-diameter unmyelinated C fibers that initiate a slightly delayed and more diffuse pain [39].

Increases in the membrane excitability of peripheral nociceptors most commonly result from inflammation-associated changes in the chemical environment of the nerve fiber [40]. Activated nociceptors as well as nonneuronal cells that reside within, or infiltrate into, the injured area (e.g., mast cells, macrophages, platelets, endothelial cells) release a variety of molecules, including neuropeptides [e.g., substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), bradykinin], neutrophins, cytokines, and eicosanoids or related lipids (e.g., prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes). These substances bind to receptors on peripheral nociceptive terminals, which leads to heightened excitability of the nerve fiber.

In addition, the release of numerous cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [41], activates the immune system which, in turn, may affect neuronal function and increase pain responses. As evidence of this, administration of a proinflammatory cytokine antagonist immediately after peripheral nerve injury or inflammation reduces pain responses [42–45]. The number of macrophages that are present at a site of injury has directly correlated with the severity of neuropathic pain [46, 47]. ICU clinicians can attempt to decrease the effects of these inflammatory mediators of pain by considering the use of anti-inflammatory agents, such as indomethacin, as an adjunctive therapy to other pain medications if the patient has no contraindications to their use [48]. Contradictions can include renal insufficiency, active peptic ulcer disease, and coagulation problems [49].

Increases in membrane excitability of dorsal root ganglia

Nociceptors have peripheral axonal branches that convey information from the periphery to ganglia outside the spinal cord and central axonal branches that convey information from the ganglia to the spinal cord. The cell bodies of peripheral nociceptors are located in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for stimuli originating in the body and in the trigeminal ganglion for stimuli from the face and mouth. Following nerve injury and in the setting of inflammation, primary sensory neurons become hyperexcitable, altering the organization of DRG neurons [50]. In addition, the DRG contains a variety of immune and immune-like cells (e.g., endothelial cells, dendritic cells, glially derived) that exist in close proximity to each DRG neuronal cell body [51]. In response to peripheral nerve damage and/or inflammation, the above nonneuronal cells, as well as immune cells, drawn into the DRG from the circulation, release proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors [52]. These responses contribute to the upregulation of cytokine receptors in DRG neurons [53–55], which leads to the release of substance P [56] and calcitonin gene-related peptide [57], which are pain-generating substances. Gradually, these events lead to DRG membrane depolarizations, and nociceptors start firing nociceptive signals from the DRG to the spinal cord at increased frequency [34]. Preventing this inflammatory cascade may keep these normally quiet cells from firing [58].

Synaptic plasticity in the spinal cord

The outer area within spinal cord consists of white matter, and the inner area is composed of gray matter. These areas comprise a busy milieu of nerve fiber transmission. The white matter contains ascending and descending neuronal tracts. The grey matter contains ten different layers, known as the Rexed laminae, on the basis of the characteristics of their neurons. The dorsal horn (posterior), where primary nociceptive afferent nerve fibers project, contains laminae I to VI, whereas the ventral horn (anterior), comprising the motor neurons, contains laminae VII to IX. Lamina X surrounds the central canal (Figure 1).

Neurons in lamina I receive direct synaptic input from Aδ and C nociceptive fibers and respond exclusively to nociceptive stimulation. Lamina II, also called the substantia gelatinosa, is made up almost exclusively of interneurons (both excitatory and inhibitory). Some of these interneurons respond only to nociceptive inputs, whereas others respond to both nociceptive and non-nociceptive stimuli [38]. Lamina III and IV contain neurons that receive input from Aβ fibers that respond predominantly to nonnoxious stimuli (e.g., touch). Importantly, lamina V contains primarily neurons that respond to a wide range of stimulus intensities as well as a combination of inputs (i.e., nociceptive and nonnociceptive, from skin, muscle, and viscera). These neurons are called wide-dynamic-range (WDR) neurons. WDR neurons receive input from Aβ and Aδ fibers as well as from C fibers, either directly on their dendrites or indirectly via excitatory interneurons that themselves receive input from peripheral C fibers [38]. Neurons in lamina VI receive input from nociceptors that mediate “fast pain” activating ascending pathways that will lead to the perception of pain as well as motor neurons involved in the withdrawal reflex (the automatic withdrawal of an extremity from a painful stimulus) [59].

During exposure to injury and subsequent activation of peripheral stimuli, the central terminals of these spinal cord nociceptors release a number of neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, substance P, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)), which bind to receptors of postsynaptic neurons in the dorsal horn spinal cord’s lamina I. When the exposure is brief and not caused by any peripheral damage, the N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) subtype of the glutamate receptor is not activated. However, when a repetitive and/or high-frequency stimulation of C-fibers occurs, it is likely that the release of glutamate and other substances leads to a prolonged, slow depolarization of the neuron, and subsequent removal of the NMDA block. When the NMDA receptor becomes unblocked, a large influx of calcium ions (Ca2+) is allowed into the postsynaptic neuron. Once inside the cell, Ca2+ promotes transcriptional changes that subsequently contribute to the maintenance of nerve sensitization [34].

In an attempt to prevent development of this sensitization, which prolongs pain, ICU clinicians can consider use of dual pharmacological therapies in certain situations. For instance, mechanically ventilated patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome and neuropathic pain can receive superior pain relief from opioids plus oral gabapentin or carbamazepine, which are both categorized as antiepileptic and antihyperalgesic drugs compared with the use of opioids alone [60, 61]. In fact, gabapentin may exert a selective effect on the nociceptive process involved in central neuronal sensitization, which is the rationale for its use in the treatment of acute postoperative pain [62]. In addition, ketamine is an NMDA-receptor antagonist that has been demonstrated to prevent hyperalgesia in postoperative major abdominal surgery patients [63]. The effectiveness of ketamine for ICU patients requires further study.

Changes that occur to nerve synapses in dorsal horn neurons as a result of stimulation that goes unblocked are frequently compared with long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP is a process that occurs in the cortex and leads to the formation of long-term memory through changes in synaptic plasticity [38]. The major synaptic alteration that contributes to central sensitization and ongoing pain is when increased activity in one set of synapses results in the facilitation of the activity in another set of synapses [34]. Long-term potentiation is responsible for the major sensory manifestations associated with central sensitization. One manifestation is allodynia, which is when a person experiences pain in a localized area that is not due to a painful stimulus but, rather, a nonpainful stimulus, such as touch. A second manifestation is called secondary hyperalgesia, which is an increase in pain sensitivity in noninjured areas beyond the area of primary injury [36]. It is likely that the phenomenon of central sensitization observed in pathologic clinical states includes both of the above processes [34, 64, 65]. If this is the case, avoiding LTP through analgesic control of acute pain is an important goal.

Changes in inhibitory control at the level of the spinal cord

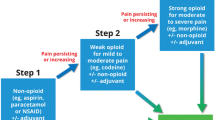

When a nociceptive signal from the periphery reaches the spinal cord, it is relayed to projection neurons, which carry the signal along ascending pathways in the spinal cord white matter to higher centers in the brain. At the same time, inhibitory interneurons interact with the terminals of primary nociceptors or projection neurons to maintain the orderly processing of sensory information [30, 66]. The inhibitory function of interneurons in the spinal cord is mediated by the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. Persistent nociceptive stimulation caused by inflammation and/or neuropathy can affect neurotransmission at this level in three ways: 1) by decreasing the number of sites that release GABA and glycine; 2) by decreasing the number of receptors to which they bind; and 3) by increasing the speed by which the inhibitory neurotransmitters are removed from the synaptic cleft [67, 68]. Thus, the disrupted function of interneurons due to loss of inhibitory control and increased stimulation could contribute to the cascade of events that lead to persistent chronic pain. Opioids, with mu-receptors in the spinal cord, can help to maintain an inhibitory effect. Indeed, opioids are the most frequently used analgesics in ICUs, and IV opioids, such as fentanyl, hydromorphone, and remifentanil, can be considered the first-line drug class of choice to treat nonneuropathic pain in critically ill patients [69]. However, follow-up of these patients is required for the early recognition of “opioid-induced hyperalgesia,” a paradoxical hyperalgesic state induced after the administration or abrupt cessation of high opioid doses. Studies of patients with chronic pain receiving opioid therapy as well as chronic users of methadone support enhanced pain perception during laboratory pain tests [37]. Nevertheless, due to the experimental setting of these studies and the lack of evidence in the ICU setting, further research is necessary to determine the presence of opioid-induced hyperalgesia in ICU patients.

Changes in descending modulation

Under normal circumstances, dorsal horn spinal cord neurons as well as the central terminals of primary afferent fibers receive additional inhibitory input from fibers that descend from supraspinal structures such as the cortex, midbrain, and brain stem to the spinal cord [30, 70–72]. For example, fibers that descend from a midbrain structure called the periaqueductal grey (PAG) (Figure 2) activate serotoninergic neurons in the rostroventral medulla (RVM) or noradrenergic neurons in the reticular formation in the pons. When these descending inhibitory neurons reach the spinal cord, they release serotonin and noradrenaline. These substances act directly or indirectly through other inhibitory interneurons to inhibit the release of noxious transmitters from primary afferent fibers or to inhibit the activation of spinal cord neurons that project a noxious stimulus to the brain [30]. Tramadol has been recommended for consideration for mild pain, because it is both a mu-receptor agonist and a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor [69]. Inhibition of reuptake inhibitors serotonin and noradrenaline maintains their prevention of nociceptive transmission. Likewise, nefopam is a nonopioid analgesic that inhibits dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin reuptake and, thus, prevents nociceptive transmission. Its effectiveness on moderate pain in a sample of 59 ICU patients has been demonstrated, although some patients experienced an increase in heart rate and decrease in mean arterial pressure [73].

Cerebral structures involved in the descending modulation of nociceptive information. Amyg, amygdala; CX, cortex; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; DRT, dorsoreticular nucleus; Hypothal, hypothalamus; NA, noradrenaline; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; PAF, primary afferent fibre; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; PAG, periaqueductal grey; Perikarya 5-HT, serotonergic perikarya; PN, projection neurones; RVM, rostroventral medulla [30] (permission granted).

Of note, the RVM in the medulla also is an important relay station for descending facilitatory influences on nociceptive spinal transmission [74, 75]. More specifically, sustained ascending nociceptive input can activate descending pain facilitatory systems from the rostroventromedial medulla (RVM) through the release of pronociceptive excitatory neurotransmitters. Thus, persistence of pain for long periods could potentially lead to more pain due to top-down effects on the spinal cord, another reason for treating pain as aggressively as possible in ICU patients.

Immune to nervous system interactions in the CNS and pain facilitation

The “sickness response” is described as the constellation of fever, increased sleep, decreased activity, and pain facilitation (i.e., sickness-induced hyperalgesia) [76]. Spinal cord immune (i.e., glia) cells have been shown to participate in pain enhancement as part of the adaptive sickness response; thus, they could be involved in pathological pain states. Studies using animal models of inflammation, peripheral nerve injury, bone cancer pain, and spinal cord injury have shown that trauma or injury to peripheral nerves leads to activation of these immune cells in the CNS [77–84].

Glia cells are numerous within the CNS, and recent evidence suggests that neurons and glia cells constitute a very important unit in the CNS [85]. Proinflammatory cytokines released in the periphery transmit signals through the blood–brain barrier to central structures where they can activate nociceptive neurons [86]. Furthermore, immune activation in the periphery can be transferred by way of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves [87, 88]. These two nerves relay information directly to the nucleus of the solitary tract, or NTS (nucleus tractus solitarii) and ventromedial medulla rather than passing through the spinal cord. These central structures can activate nociceptive neurons of the brainstem and give rise to the final branch of the sickness-induced hyperalgesia pathway, which consists of descending facilitatory fibers that target glia cells in the spinal cord. Activation of glia cells leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines within the CNS, which bind to membrane receptors expressed by pain-responsive dorsal horn neurons, increasing their excitability [89–91]. Finally, one set of activated glial cells can activate another set of glial cells, which augments nociceptive activation. In short, there is a positive feedback mechanism that intensifies and perpetuates pain. Glial cells become activated during both acute inflammation [92, 93] and peripheral nerve damage, which can lead to the development of neuropathic pain [94].

Central sensitization in brain areas

The perception of pain during both acute injury and in chronic pain states undergoes substantial processing at supraspinal levels (Figure 3) and involves many brain areas. A number of nociceptive pathways project from the spinal cord dorsal horn directly to brainstem and limbic system areas. These pathways directly activate brain structures involved in rudimentary emotional responses to pain, such as autonomic nervous system (ANS) activation, escape, motor responses, arousal, and fear, which require a minimum amount of cognition [95].

Supraspinal areas involved in the modulation of pain. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AMYG, amygdala; HT, hypothalamus; M1, motor cortex; MDvc, ventrocaudal part of the medial thalamic dorsal nucleus; PAG, periaqueductal grey; PB, parabrachial nucleus of the dorsolateral pons; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PPC, posterior parietal complex; PF, prefrontal cortex; S1, S2, first and second somatosensory cortical areas, respectively; SMA, supplementary motor area; VMpo, ventromedial part of the posterior thalamic nuclear complex; VPL, ventroposterior lateral thalamic nucleus[95] (permission granted).

A major pathway through which nociceptive input reaches the brain is the lateral spinothalamic tract. This tract projects from the spinal cord to the thalamus and from there to limbic cortical areas, such as the amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and insular cortex (IC or insula). Another component of the spinothalamic tract projects to somatosensory nuclei of the thalamus, which relays nociceptive information to somatosensory (S-1 and S-2) cortices [96]. This pathway is implicated in the appreciation of the intensity and quality of pain sensations [95]. S1 cortex is generally associated with sensory-discriminative aspects of pain, such as pain intensity and location [97]; S2 cortex likely has additional affective/cognitive functions.

There is a large matrix of pathways and brain areas that work together to influence the pain experience. Some neuronal pathways from S-1/S-2 cortices extend to posterior parietal cortical areas (PPC) and IC, and from IC to ACC, the amygdala, and hippocampus [98]. The IC and ACC are important for affective-motivational and certain cognitive aspects of pain, including attention, anticipation, and evaluation [99–101]. Posterior parietal cortical areas (PPC) integrate somatosensory input with other sensory modalities, such as learning and memory [98, 102]. Thus, pain is a whole brain experience.

The convergence of pain pathways that occurs in the brain provides support for a mechanism whereby multiple neural sources, including the limbic system, contribute to pain affect; i.e., the emotional component of pain. Convergence of neural pathways at the level of the limbic system would be consistent with a mechanism in which somatic perceptual and cognitive features of pain would be integrated with attentional and emotion mechanisms. Thus, the limbic system may have a complex pivotal role in interrelating (facilitating or inhibiting) attentional and evaluative functions with that of establishing response priorities [102, 103].

Sensory and affective dimensions of pain were, until recently, believed to be the result of neural processing in separate but parallel neuronal pathways and brain centers. A more current view proposes that the sensory and affective experience of pain is the result of processing that occurs in both serial and parallel ways [95]. That is, regions of the brain involved in somatosensory processing also are important for the processing of the affective dimension of pain. This knowledge could be particularly useful to explore the transition from acute to chronic pain,because the neurobiological dysregulation, manifested at various levels of human functioning (e.g., behavioral, affective, sensory), could open a window on the sequence of events that leads to the establishment of chronic pain. If pain persists over a long period of time, response priorities might change. Pain unpleasantness endured over time engages prefrontal cortical areas involved in reflection and rumination over the future implications of a persistent pain condition [95]. These reflections usually involve perceived interference with one’s body, fear for loss of regular activity, and possible difficulties with enduring pain over time; i.e., after discharge from an ICU [17–19]. In fact, patients with chronic pain are known to have higher postoperative pain scores and a longer time to pain resolution after surgery. Thus, identifying and treating their pain aggressively after surgery could positively impact their long-term pain state [104].

The prefrontal cortex (PFC)

The prefrontal cortex plays an important role in higher order cognitive functions, such as planning, decision-making, reward expectancy, avoidance of risky choices, and goal-directed behaviors, in both animals and humans [105]. It receives major input from limbic structures, such as the amygdala, and is considered an important area for value-based decision-making [106, 107]. Although limbic structures, such as amygdala, ACC, and insula, appear to be important to effect cognitive and emotional factors of pain, they themselves seem to be governed by the prefrontal cortex [108]. Consistent with these observations, the brain area most frequently activated in chronic pain patients is the prefrontal cortex [109]. It is currently believed that, in normal situations, the prefrontal cortex and a network of other interconnected neural structures exert an inhibitory influence on subcortical activation associated with ANS activation and escape behaviors [110]. For example, when a threatening stimulus, such as perceived pain, alarms the subcortical network, the prefrontal cortex diminishes the inhibitory control to allow for sympathetic system activation and escape behaviors. These responses and behaviors may help to account for increases in heart rate and blood pressure and facial expressions observed by ICU clinicians during a patient’s pain experience. However, vital signs cannot be used alone to determine whether pain is present, because they are insensitive measures of pain [111, 112].

In the case of excessive activation of this inhibitory network in the prefrontal cortex and in other interconnected neural structures activated in the context of persistent pain, the system might become dysregulated and even disrupted. Such a neurophysiological state could manifest itself as attentional, affective, and/or autonomic dysregulation [110]. In fact, sometimes patients with chronic pain are challenged by affective disorders (i.e., depression, anxiety), exhibit avoidance fears and responses, and develop behaviors that do not have any obvious adaptive character [113]. Thus, effectively managing acute pain in ICU patients may help to prevent the development of affective disorders that often accompany chronic pain.

Conclusions

Long-term potentiation of synaptic responses in combination with disinhibition/facilitation of descending modulatory endogenous pain circuits and the immune system’s activation seem to be critical in the development and maintenance of conditions of central sensitization and chronic pain. Initially, these alterations were observed at the level of the spinal cord. Interestingly, similar changes are currently being observed as involving several brain areas associated with sensory perception, transmission, modulation, and memory of pain [114]. At the same time, altered emotional and cognitive processing is considered to be an important contributor to the excessive suffering that is a hallmark of chronic pain conditions [115]. Because the pain experience comprises both sensory and emotional components, as presented earlier in the definition of pain by IASP [20], some theorize that physiological alterations that are allowed to persist may be associated with augmentation in the perceptual, affective, and/or motivational components of the pain experience [95, 109, 113].

Although evidence about transition from acute to chronic pain is new and still evolving and observations are mainly derived from experiments under controlled laboratory settings, this evidence is creating new areas for exploration. Of particular concern is the need to better understand physiological modifications that may occur during the transition of a patient from acute to chronic pain and to prevent this transition as much as possible. Ultimately, the goal in critical care is to appreciate the potential for this transition and attempt to preempt it by aggressive use of therapeutic interventions for pain. In addition, when an ICU patient is recognized as having chronic pain along with their acute condition, clinicians can appreciate the complexity of this condition and use interventions that move toward targeting neuropathic pain mechanisms and/or prevention of opioid-induced hyperalgesia [10, 37]. Future basic and clinical research is warranted that tests interventions that could be used to modulate both the somatic and the affective dimension of the acute pain experience and potentially prevent the transition from acute-to-chronic pain.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Anterior cingulate cortex

- Amyg:

-

Amygdala

- ANS:

-

Autonomic nervous system

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CX:

-

Cortex

- DRG:

-

Dorsal root ganglia

- DRT:

-

Dorsoreticular nucleus

- GABA:

-

γ-Aminobutyric acid

- Hypothal:

-

Hypothalamus

- IASP:

-

International association for the study of pain

- IC:

-

Insular cortex or insula

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1β

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- LTP:

-

Long-term potentiation

- mGluR I:

-

Glutamate Receptor subtype I

- NA:

-

Noradrenaline

- NMDA:

-

N-methyl D-aspartate sub-type of the glutamate receptor

- NTS:

-

Nucleus tractus solitarius

- PAF:

-

Primary afferent fibre

- PAG:

-

Periaqueductal grey

- PBN:

-

Parabrachial nucleus

- PFC:

-

Prefrontal cortex

- PPC:

-

Posterior parietal cortex

- RVM:

-

Rostroventral medulla

- S-1:

-

S-2: Somatosensory cortices

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor α

- WDR neurons:

-

Wide dynamic range neurons.

References

Erstad BL, Puntillo K, Gilbert HC, Grap MJ, Li D, Medina J, et al.: Pain management principles in the critically ill. Chest 2009, 135: 1075–1086. 10.1378/chest.08-2264

Stanik-Hutt JA, Soeken KL, Belcher AE, et al.: Pain experiences of traumatically injured patients in a critical care setting. Am J Crit Care 2001, 10: 252–259.

Nelson JE, Meier DE, Oei EJ, Nierman DM, Senzel RS, Manfredi PL, et al.: Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 277–282. 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00010

Puntillo KA, White C, Morris AB, Perdue ST, Stanik-Hutt J, Thompson CL, et al.: Patients' perceptions and responses to procedural pain: Results from thunder project II. Am J Crit Care 2001, 10: 238–251.

Chanques G, Sebbane M, Barbotte E, Viel E, Eledjam JJ, Jaber S: A prospective study of pain at rest: Incidence and characteristics of an unrecognized symptom in surgical and trauma versus medical intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology 2007, 107: 858–860. 10.1097/01.anes.0000287211.98642.51

Gelinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M: Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care 2006, 15: 420–427.

Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta A, Novel E, Deschaux I, et al.: Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 2258–2263. 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004

Gelinas C: Management of pain in cardiac surgery ICU patients: Have we improved over time? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007, 23: 298–303. 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.002

Schelling G, Stoll C, Haller M, Briegel J, Manert W, Hummel T, et al.: Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 1998, 26: 651–659. 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011

Katz J, Seltzer Z: Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors. Exp Rev Neurother 2009, 5: 723–744.

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Sedrakyan A, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, et al.: Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: A systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 611–620. 10.1007/s00134-005-2592-6

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR, Mendez-Tellez PA, Herridge MS, Guallar E, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM: Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 1115–1124. 10.1007/s00134-006-0217-3

Der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans D, Vroom M, Nollet F: Poor functional recovery after critical illness.A longitudinal study. J Rehab Med 2009, 41: 1041–1048. 10.2340/16501977-0443

Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Paparella L, Buoninsegni LT, Barboni E: Outcome predictors and quality of life of severe burn patients admitted to intensive care unit. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2010, 18: 24–32. 10.1186/1757-7241-18-24

Zimmer A, Rothaug J, Mescha S, Reinhart K, Meissner W, Marx G: Chronic pain after surviving sepsis. Crit Care 2006,10(Suppl 1):P421. 10.1186/cc4768

Jose GM H, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers GJP, Rommes JH, Jan Bakker J: The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest 2008, 133: 377–385. 10.1378/chest.07-1217

Jacodic HK, Jakodic K, Podbregar M: Long-term outcome and quality of life of patients treated in a surgical intensive care: a comparison between sepsis and trauma. Crit Care 2006, 10: R134. 10.1186/cc5047

Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, MacLennan G, Vale L: Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care 2010, 14: R6. 10.1186/cc8848

Timmers TK, Verhofstad MH, Moons KG, van Beeck EF, Leenen LP: Long-term quality of life after surgical intensive care admission. Arch Surg 2011, 146: 412–418. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.279

International Association for the Study of Pain Taxonomy http://www.iasp.pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Pain_Definitions

Acute Pain Management Guideline P: Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Clinical Practice Guideline. In AHCPR Pub. No. 92–0032. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1992.

Dubner R: The neurobiology of persistent pain and its clinical implications. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol 2004, 57: 3–7.

Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ: Central sensitization and LTP: Do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci 2003, 26: 696–705. 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017

Woolf CJ, Salter MW: Neuronal plasticity: Increasing the gain in pain. Science (New York) 2000, 288: 1765–1769. 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765

Woolf CJ, Ma Q: Nociceptors–noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron 2007, 55: 353–364. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016

Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, Cooper AB, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Barr A, Cook D, Slutsky AS: One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003, 348: 683–693. 10.1056/NEJMoa022450

Kehlet H, Rathmell JP: Persistent postsurgical pain: the path forward through better design of clinical studies. Anesthesiology 2010, 112: 514–515. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cf423d

Mosby: Mosby's Medical Dictionary. 8th edition. Elsevier, US; 2009.

Merriam-Webster: Encyclopaedia Britannica online. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

Millan MJ: Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol 2002, 66: 355–474. 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00009-6

The Free Dictionary. Farlex, Inc, ; 2012. http://www.thefreedictionary.com

Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009, 139: 267–284. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028

Hughes JR: Post-tetanic potentiation. Physiol Rev 1958, 38: 91–113.

Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain 2009, 10: 895–926. 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012

Macrae WA, Davies HTO: Chronic postsurgical pain. In Epidemiology of Pain. Edited by: Crombie IK. IASP Press, Seattle; 1999:125–142.

Sandkuhler J: Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiol Rev 2009, 89: 707–758. 10.1152/physrev.00025.2008

Lee M, Silverman S, Hansen H, Patel V, Manchikanti L: A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician 2011, 14: 145–161.

Bausbaum AI, Jessell T: The perception of pain. In Principles of Neuroscience. Edited by: Kandel ER, Schwartz J, Jessell T. Appleton and Lange, New York; 2000:472–491.

Meyer RA: Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron 2006, 52: 77–92. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021

McMahon SB, Bennett DLH, Bevan S: Inflammatory mediators and modulators of pain. In Wall and Melzack's Textbook of Pain. Edited by: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Elsevier, Philadelphia; 2008:49–72.

Ritner HL, Machelska H, Stein C: Immune system pain and analgesia. In Science of Pain. Edited by: Bausbaum AI, Bushnell M. Academic Press, Oxford, England; 2009:407–427.

Lindenlaub T, Teuteberg P, Hartung T, Sommer C: Effects of neutralizing antibodies to TNF-alpha on pain-related behavior and nerve regeneration in mice with chronic constriction injury. Brain Res 2000, 866: 15–22. 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02190-9

Schafers M, Brinkhoff J, Neukirchen S, Marziniak M, Sommer C: Combined epineurial therapy with neutralizing antibodies to tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 receptor has an additive effect in reducing neuropathic pain in mice. Neurosci Lett 2001, 310: 113–116. 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02077-8

Sommer C, Petrausch S, Lindenlaub T, Toyka KV: Neutralizing antibodies to interleukin 1-receptor reduce pain associated behavior in mice with experimental neuropathy. Neurosci Lett 1999, 270: 25–28. 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00450-4

Twining CM, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Chacur M, Martin D, Poole S, Marsh H, Maier SF, Watkins LR: Peri-sciatic proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and complement induce mirror-image neuropathic pain in rats. Pain 2004, 110: 299–309. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.008

Cui JG, Holmin S, Mathiesen T, Meyerson BA, Linderoth B: Possible role of inflammatory mediators in tactile hypersensitivity in rat models of mononeuropathy. Pain 2000, 88: 239–248. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00331-6

Liu T, van Rooijen N, Tracey DJ: Depletion of macrophages reduces axonal degeneration and hyperalgesia following nerve injury. Pain 2000, 86: 25–32. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00306-1

Rapanos T, Murphy P, Szalai JP, Burlacoff L, Lam-McCulloch J, Kay J: Rectal indomethacin reduces postoperative pain and morphine use after cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth 1999, 46: 725–730. 10.1007/BF03013906

Hynninen MS, Cheng DC, Hossain I, Carroll J, Aumbhagavan SS, Yue R, et al.: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in treatment of postoperative pain after cardiac surgery. CanJ Anaesth 2000, 47: 1182–1187. 10.1007/BF03019866

Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011,152(3 Suppl):S2-S15.

Watkins LR, Maier SF: Beyond neurons: Evidence that immune and glial cells contribute to pathological pain states. Physiol Rev 2002, 82: 981–1011.

Hu P, McLachlan EM: Macrophage and lymphocyte invasion of dorsal root ganglia after peripheral nerve lesions in the rat. Neuroscience 2002, 112: 23–38. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00065-9

Ohtori S, Takahashi K, Moriya H, Myers RR: TNF-alpha and TNF-alpha receptor type 1 upregulation in glia and neurons after peripheral nerve injury: studies in murine DRG and spinal cord. Spine 2004, 29: 1082–1088. 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00006

Schafers M, Lee DH, Brors D, Yaksh TL, Sorkin LS: Increased sensitivity of injured and adjacent uninjured rat primary sensory neurons to exogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha after spinal nerve ligation. J Neurosci 2003, 23: 3028–3038.

Schafers M, Sorkin LS, Geis C, Shubayev VI: Spinal nerve ligation induces transient upregulation of tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 in injured and adjacent uninjured dorsal root ganglia in the rat. Neurosci Lett 2003, 347: 179–182. 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00695-5

Morioka N, Inoue A, Hanada T, Kumagai K, Takeda K, Ikoma K, et al.: Nitric oxide synergistically potentiates interleukin-1 beta-induced increase of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA levels, resulting in the facilitation of substance P release from primary afferent neurons: involvement of cGMP-independent mechanisms. Neuropharmacology 2002, 43: 868–876. 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00143-0

Hou L, Li W, Wang X: Mechanism of interleukin-1 beta-induced calcitonin gene-related peptide production from dorsal root ganglion neurons of neonatal rats. J Neurosci Res 2003, 73: 188–197. 10.1002/jnr.10651

Sandkuhler J: Understanding LTP in pain pathways. Mol Pain 2007, 3: 9. 10.1186/1744-8069-3-9

Goshgarian H: Anatomy and function of the spinal cord. In Spinal Cord Medicine: Principles and Practice. Edited by: Vernon WL, Cardenas DD, Cutter NC, Frost FS, Hammond MC, Lindblom LB, Perkash I, Waters R, Woolsey RM. Demos Medical Publishing, New York; 2003:15–35.

Pandey CK, Bose N, Garg G, Singh N, Baronia A, Agarwal A, et al.: Gabapentin for the treatment of pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Anesth Analg 2002, 95: 1719–1723. 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00046

Pandey CK, Raza M, Tripathi M, Navkar DV, Kumar A, Singh UK: The comparative evaluation of gabapentin and carbamazepine for pain management in Guillain-Barrésyndrome patients in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 2005, 101: 220–225. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000152186.89020.36

Pandey CK, Singhal V, Kumar A, Lakra A, Ranjan R, Pal R, Raza M, Singh UK, Singh PK: Gabapentin provides effective postoperative analgesia whether administered preemptively or post-incision. Can J Anesth 2005, 52: 827–831. 10.1007/BF03021777

Joly V, Richebe R, Guignard B, Fletcher D, Maurette P, Sessler DI, et al.: Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology 2005, 103: 147–155. 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00022

Luo C, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R, Kuner R: Activity-dependent potentiation of calcium signals in spinal sensory networks in inflammatory pain states. Pain 2008, 140: 358–367. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.008

Woolf CJ: Windup and central sensitization are not equivalent. Pain 1996, 66: 105–108.

Neumann S, Doubell TP, Leslie T, Woolf CJ: Inflammatory pain hypersensitivity mediated by phenotypic switch in myelinated primary sensory neurons. Nature 1996, 384: 360–364. 10.1038/384360a0

Cherubini E, Conti F: Generating diversity at GABAergic synapses. Trends Neurosci 2001, 24: 155–162. 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01724-0

Lee JW, Siegel SM, Oaklander AL: Effects of distal nerve injuries on dorsal-horn neurons and glia: Relationships between lesion size and mechanical hyperalgesia. Neuroscience 2009, 158: 904–914. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.010

Mattia C, Savoia G, Paoletti F, Piazza O, Albanese D, Amantea B, et al.: SIAARTI recommendations for analgo-sedation in intensive care unit. Minerva Anestesiol 2006, 72: 769–805.

Porreca F, Ossipov MH, Gebhart GF: Chronic pain and medullary descending facilitation. Trends Neurosci 2002, 25: 319–325. 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02157-4

Urban MO, Gebhart GF: Supraspinal contributions to hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96: 7687–7692. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7687

Watkins LR, Maier SF: Implications of immune-to-brain communication for sickness and pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96: 7710–7713. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7710

Chanques G, Sebbane M, Constantin JM, Ramillon N, Jung B, Cisse M, Lefrant JY, Jader S: Analgesic efficacy and haemodynamic effects of nefopam in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth 2011, 106: 336–343. 10.1093/bja/aeq375

Fields HL, Heinricher MM: Anatomy and physiology of a nociceptive modulatory system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1985, 308: 361–374. 10.1098/rstb.1985.0037

Porreca F, Burgess SE, Gardell LR, Vanderah TW, Malan TP, Ossipov MH, et al.: Inhibition of neuropathic pain by selective ablation of brainstem medullary cells expressing the mu-opioid receptor. J Neurosci 2001, 21: 5281–5288.

Wiertelak EP, Smith KP, Furness L, Mooney-Heiberger K, Mayr T, Maier SF, et al.: Acute and conditioned hyperalgesic responses to illness. Pain 1994, 56: 227–234. 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90098-1

Fu KY, Light AR, Maixner W: Relationship between nociceptor activity, peripheral edema, spinal microglial activation and long-term hyperalgesia induced by formalin. Neuroscience 2000, 101: 1127–1135. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00376-6

Meller ST, Dykstra C, Grzybycki D, Murphy S, Gebhart GF: The possible role of glia in nociceptive processing and hyperalgesia in the spinal cord of the rat. Neuropharmacology 1994, 33: 1471–1478. 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90051-5

Milligan ED, O'Connor KA, Nguyen KT, Armstrong CB, Twining C, Gaykema RP, et al.: Intrathecal HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 induces enhanced pain states mediated by spinal cord proinflammatory cytokines. J Neurosci 2001, 21: 2808–2819.

Milligan ED, Twining C, Chacur M, Biedenkapp J, O'Connor K, Poole S, et al.: Spinal glia and proinflammatory cytokines mediate mirror-image neuropathic pain in rats. J Neurosci 2003, 23: 1026–1040.

Raghavendra V, Tanga F, DeLeo JA: Inhibition of microglial activation attenuates the development but not existing hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003, 306: 624–630. 10.1124/jpet.103.052407

Sjostrand J: Neuroglial proliferation in the hypoglossal nucleus after nerve injury. Exp Neurol 1971, 30: 178–189. 10.1016/0014-4886(71)90232-9

Watkins LR, Wiertelak EP, Furness LE, Maier SF: Illness-induced hyperalgesia is mediated by spinal neuropeptides and excitatory amino acids. Brain Res 1994, 664: 17–24. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91948-8

Watkins LR, Maier SF: Glia: a novel drug discovery target for clinical pain. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003, 2: 973–985. 10.1038/nrd1251

Ren K, Dubner R: Neuron-glia crosstalk gets serious: role in pain hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008, 21: 570–579. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830edbdf

Quan N, Herkenham M: Connecting cytokines and brain: a review of current issues. Histol Histopathol 2002, 17: 273–288.

Romeo HE, Tio DL, Rahman SU, Chiappelli F, Taylor AN: The glossopharyngeal nerve as a novel pathway in immune-to-brain communication: Relevance to neuroimmune surveillance of the oral cavity. J Neuroimmunol 2001, 115: 91–100. 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00270-3

Watkins LR, Maier SF, Goehler LE: Cytokine-to-brain communication: a review and analysis of alternative mechanisms. Life Sci 1995, 57: 1011–1026. 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02047-M

Constandil L, Hernandez A, Pelissier T, Arriagada O, Espinoza K, Burgos H, et al.: Effect of interleukin-1beta on spinal cord nociceptive transmission of normal and monoarthritic rats after disruption of glial function. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11: R105. 10.1186/ar2756

Reeve AJ, Patel S, Fox A, Walker K, Urban L: Intrathecally administered endotoxin or cytokines produce allodynia, hyperalgesia and changes in spinal cord neuronal responses to nociceptive stimuli in the rat. Eur JPain (London, Engl) 2000, 4: 247–257. 10.1053/eujp.2000.0177

Watkins LR, Maier SF: Immune regulation of central nervous system functions: From sickness responses to pathological pain. J Intern Med 2005, 257: 139–155. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01443.x

Chacur M, Gutierrez JM, Milligan ED, Wieseler-Frank J, Britto LR, Maier SF, et al.: Snake venom components enhance pain upon subcutaneous injection: an initial examination of spinal cord mediators. Pain 2004, 111: 65–76. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.06.001

Watkins LR, Martin D, Ulrich P, Tracey KJ, Maier SF: Evidence for the involvement of spinal cord glia in subcutaneous formalin induced hyperalgesia in the rat. Pain 1997, 71: 225–235. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)03369-1

Ledeboer A, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Frank MG, Mahony JH, Maier SF, et al.: Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain 2005, 115: 71–83. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.009

Price DD: Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science (New York) 2000, 288: 1769–1772. 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769

Melzack R, Casey KL: Sensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: a new conceptual model. In Skin Senses. Edited by: Kenshalo DR. Thomas C, Springfield, IL; 1968:423–439.

Craig AD: Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2003, 13: 500–505. 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00090-4

Friedman DP, Murray EA, O'Neill JB, Mishkin M: Cortical connections of the somatosensory fields of the lateral sulcus of macaques: Evidence for a corticolimbic pathway for touch. J Comp Neurol 1986, 252: 323–347. 10.1002/cne.902520304

Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK: Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur JPain (London, Engl) 2005, 9: 463–484. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001

Rhudy JL, Williams AE, McCabe KM, Russell JL, Maynard LJ: Emotional control of nociceptive reactions (ECON): Do affective valence and arousal play a role? Pain 2008, 136: 250–261. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.031

Seminowicz DA, Mikulis DJ, Davis KD: Cognitive modulation of pain-related brain responses depends on behavioral strategy. Pain 2004, 112: 48–58. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.027

Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ: Insula of the old world monkey. III: Efferent cortical output and comments on function. J Comp Neurol 1982, 212: 38–52. 10.1002/cne.902120104

Zhang L, Zhang Y, Zhao ZQ: Anterior cingulate cortex contributes to the descending facilitatory modulation of pain via dorsal reticular nucleus. Eur J Neurosci 2005, 22: 1141–1148. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04302.x

Chapman CR, Davis J, Donaldson GW, Naylor J, Winchester D: Postoperative pain trajectories in chronic pain patients undergoing surgery: the effects of chronic opioid pharmacotherapy on acute pain. J Pain 2011, 12: 1240–1246. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.07.005

Tanji J, Hoshi E: Behavioral planning in the prefrontal cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2001, 11: 164–170. 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00192-6

Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Anderson SW: Dissociation of working memory from decision making within the human prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 1998, 18: 428–437.

Daw ND, O'Doherty JP, Dayan P, Seymour B, Dolan RJ: Cortical substrates for exploratory decisions in humans. Nature 2006, 441: 876–879. 10.1038/nature04766

Quadflieg S, Mohr A, Mentzel HJ, Miltner WH, Straube T: Modulation of the neural network involved in the processing of anger prosody: the role of task-relevance and social phobia. Biol Psychol 2008, 78: 129–137. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.01.014

Apkarian AV: Pain perception in relation to emotional learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008, 18: 464–468. 10.1016/j.conb.2008.09.012

Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF: The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J Psychosom Res 2006, 60: 113–124. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074

Siffleet J, Young J, Nikoletti S, Shaw T: Patients' self-report of procedural pain in the intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs 2007, 16: 2142–2148. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01840.x

Young J, Siffleet J, Nikoletti S, Shaw T: Use of a behavioural pain scale to assess pain in ventilated, unconscious and/or sedated patients. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2006, 22: 32–39. 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.04.004

Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Han JS: The amygdala and persistent pain. Neuroscientist 2004, 10: 221–234. 10.1177/1073858403261077

Zhuo M: A synaptic model for pain: long-term potentiation in the anterior cingulate cortex. Mol Cells 2007, 23: 259–271.

Izard CE: Emotion theory and research: highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Psychol 2009, 60: 1–25. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MK developed the initial draft of this manuscript as part of her PhD dissertation. KP was MK’s dissertation advisor. Both MK and KP have made significant contributions to the analysis of research in this review and drafting and revising the review for intellectual content. Both MK and KP have given final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyranou, M., Puntillo, K. The transition from acute to chronic pain: might intensive care unit patients be at risk?. Ann. Intensive Care 2, 36 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-2-36

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-2-36